Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRossellini's Requiem

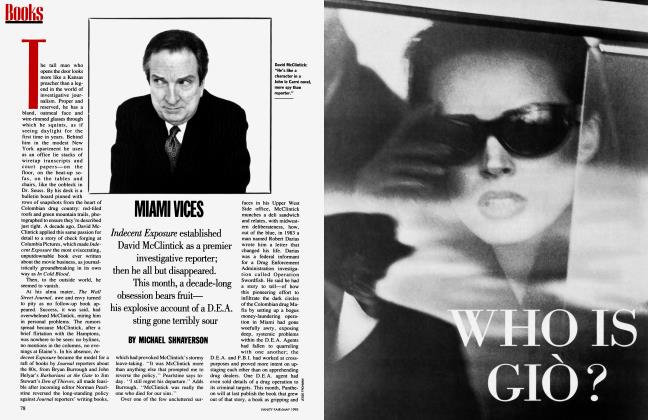

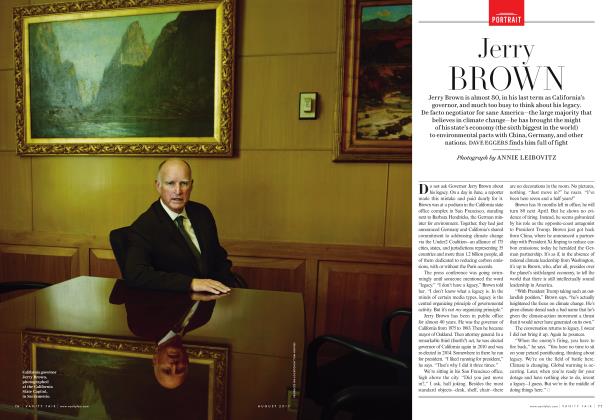

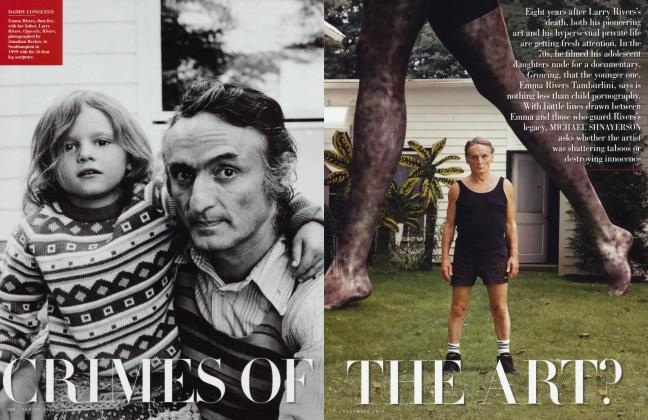

Franco Rossellini made an art of befriending the famous— from Maria Callas and Pier Paolo Pasolini to Imelda Marcos and Doris Duke—and, even more, of talking about them. A year after Rossellini's death from AIDS, BEN BRANTLEY describes the eccentric valor and pyrotechnic storytelling of the film producer's last months

BEN BRANTLEY

On the day I met Franco Rossellini, four months before he died last June, he assured me his life had been glorious. The 56-yearold Italian movie producer, a man who had spent much time playing thorny courtier to the famous, had been diagnosed with AIDS in the spring of 1991, and he seemed at pains to make sense of an existence spent mostly in fragmented transit and on the periphery of more celebrated lives. "Ah, my bio-grapher," he exclaimed, stretching each syllable, as he entered the living room of his two-bedroom Manhattan apartment near Carnegie Hall. A theatrical six feet five, Rossellini had the head of a balding, regal parrot. He was dressed casually—a T-shirt printed with the name of Cabrini Medical Center, khaki pants, boat shoes. But his eyeglasses—lemonshaped with wide black arms—immediately evoked the Rome of La Dolce Vita (a movie in which he played a bit part), and his manner was pure silk dressing gown. I had seldom met anyone with such a ravenous will to impress. He indicated the gallery of photographs which dominated the room with an expansive sweep of his cigarette holder. "These are my icons, my heroes," he said. "Let's face it, who has the claim to such a life? I've been very spoiled."

Some of the pictures were of artists; others were of people known simply for their money and how they spent it. Nearly all of them were famous. His friendships with them had become, in a strange way, his profession. He was well aware that knowing, and betraying, their secrets—and being able to present his idols stripped, as it were, to their ratty underwear—was what guaranteed him power and access in a milieu in which gossip was treated as an art form. These friends ranged from Imelda Marcos—whom he planned to meet in the Philippines, where she would wage her unsuccessful bid for the presidency—to Rudolf Nureyev; from Doris Duke, the reclusive tobacco heiress, to Pier Paolo Pasolini, the controversial poet-filmmaker, for whom he had produced three films. They would form the corps of dramatis personae in the stories he would tell me in the succeeding months—tirelessly, even from hospital beds. In one breath, he could both apotheosize and excoriate his subjects and perceive no contradiction. "Monsters," "provocateurs," he would call them with proprietary affection; "impossible people."

Chief among the pantheon was Maria Callas, the opera diva and the most "impossible" of all. He had seen her through numerous crises, he said, diverting her with jokes and fiery arguments. After the blow of her beloved Aristotle Onassis's marriage to Jacqueline Kennedy, he had even created a movie for her: Pasolini's Medea, released in 1970. Now it seemed that Callas, who died in 1977, was reciprocating, appearing to Rossellini in nightly visitations. Speaking in the Venetian dialect in which they often conversed, she would offer imperious, but optimistic, counsel on his physical and spiritual condition. She signaled her arrival, he told me, by toppling the framed photograph which showed her on location in Turkey in elaborate queenly headdress, looking adoringly at him.

"Don't make fun of me," he admonished in one of the moments of bald insight which would periodically startle amid the exaggerations and barbed whimsy. "I'm grateful to these characters that are so printed into my soul—they keep me company. They are printed. It's not a diplomatic passport like Mrs. Marcos has, that they can come and visit me. But I am lucky that I have an inside that helps me to survive, because I really cannot take it. The other day, after this thing with Callas, I change completely. Completely. I feel superb."

Franco Rossellini grew up in Rome in, as he put it, an "incredible atmosphere of genius" and much-publicized drama. He appears to have fallen in love early with the distorting, glamorizing mirror which fame held up to the lives of those around him. The son of the composer Renzo Rossellini, he called his uncle Roberto Rossellini, the film director responsible for such neo-realist cornerstones as Open City and Paisan, his true spiritual father. Born in 1935, Franco was 13 when Roberto began his notorious romance with the married film actress Ingrid Bergman, whom he subsequently wed. Their romance drew public censure from the floor of the U.S. Senate, a circumstance which he spoke of in a tone suggesting a French aristocrat's recalling of the Reign of Terror.

He was a pure example of a disappearing breed: the man who talks for his supper, supremely adept at keeping the easily bored from seeming boring to themselves.

Franco described the Rossellinis as a tribe of "universal artists," but seldom dwelled on the specifics of their artistic accomplishments. The point for him was the family's defiant flouting of convention and the breadth of the international interest it provoked. I never knew if the stories he told me about his family were things he had actually seen, or heard from relatives, or simply read in the books he kept around him. For him, that didn't matter; it was his birthright to tell them, just as it was his birthright to claim attention with the willful, extravagant behavior he so loved describing in others. In his own eyes, he had achieved greatness by association.

The sense of self-importance engendered by his early years would lead him to court, for the rest of his life, "exceptional people" with similarly tempestuous histories and a disregard for middle-class morality. He would himself become the producer of several films which would get a lot of attention: those he made with Pasolini became art-house classics; another, the controversial epic Caligula, a loud succes de scandale. But he seldom wanted to talk about filmmaking, only the personalities of the people involved. He clearly liked the commotion, the daily histrionics, of a movie set; films themselves bored him. "I hate movies," he said one day. "It was the only thing I could do. To me, they're very tiring; I don't discuss them."

A month before he died, his friend of some 40 years, the Italian countess Marina Cicogna, who co-produced two Pasolini/Rossellini films, noted, "The one thing I've never seen Franco have in life is a direction." And by the end of his life, he was identified largely as a "court jester"—or, even worse, "gigolo"—to the very rich. They were labels he despised. "I'm not a clown," he said. "I'm a very bright person, and to a lot of people, I'm very intimidating." All the same, he came to live off the stories he had accumulated, much as Truman Capote did in the period when his major writing was well behind him. They were his passage to private planes and stellar dinner parties. He was, finally, a highly evolved example of a disappearing breed, one largely peculiar to the idle classes: the man who talks for his supper. He was supremely adept at keeping the easily bored from seeming boring to themselves.

Even after many of his favorite subjects had died or dropped him, as he claimed bitterly, when they learned he had AIDS, he continued to talk about them to anyone who would listen. He would surround himself with biographies, searching the indexes for references to his name. His mood swings were vast, ranging from childlike sentimentality to vitriolic contempt. On some days, he wondered if he was wasting my time. ''What a stupid life I had," he once told me, nearly spitting the sentence. ''Day by day, I think it's very interesting, but on the whole it's a terrible stupidity."

But as soon as he set himself on the path of a story, the gloom would evaporate, and the room itself would seem to spring into animation. In the telling, they were vibrant, fully fleshed tales, but whenever I tried to repeat them to other people, they seemed to shrink into triviality, silliness, even nastiness. I learned early on not to look for coherence or factual accuracy in them. His cousin Isabella Rossellini, the actress and model, whose parents were Roberto Rossellini and Ingrid Bergman, warned me, ' 'Every day he will change the story, because Franco is compelled to lie a little bit all the time. In the family, we lift the shoulders and say, 'Here he goes again... ' "

Rossellini himself did not see this as a criticism. ''We are Italians, we live on lies," he said. ''Otherwise, you cannot survive. Sometimes I pretend something which is not. Doris, Doris [Duke] is unable to lie. But she can be a hell of a bore. Oh, my dear, I tell you that. And Jackie [Onassis] cannot lie. But who wants to hear Jackie, even lying? You understand? I am a fucking liar, and everybody loves me."

There was a strong current of malice in many of his portraits, and no secret— no matter how compromising in its sexual or financial details—was untellable if it added piquancy to the tale. He once exploded viciously on the subject of the ex-wife of a multimillionaire (she had sued him for money she had once lent him), detailing the sexual practices with which he believed she had earned her fortune. When I asked if he still talked to her, he seemed genuinely surprised. ''Of course," he said. ''She's a friend."

Marina Cicogna admitted she had sometimes been offended by what she saw as ''major treason" in Rossellini's behavior. But she added, ''I think he brought to these people a zest for life and a humor and a way of seeing things that was so much more precious than the kind of life that these people live. I mean, they're rather solemn and not terribly funny people, you know. Even Maria—who was an extraordinary talent—was not the funniest woman in the world. Actually, she was rather dull."

Violent quarrels with the people he was closest to, including Callas, were customary in his life. But he was usually forgiven, and people continued to invite him to ride on their jets and stay on their yachts and private islands. Doris Duke even set him up in a cottage on her estate in Somerville, New Jersey, and, along with other of his wealthier friends, helped to pay his medical bills in his last years. He saw nothing shameful in this. ''I am a very poor person," he said with ferocious pride. ''I have no money. No money. But I live like a billionaire."

Inspired by the pictures carefully logged into more than a dozen photo albums, he spoke of traveling with Mrs. Marcos when she returned to her homeland in 1991, for the first time since the overthrow of her husband's government, on a chartered 747 (''She had four statues of the Madonna, each carried by a special man, and they were sitting all in first class, with the seat belt on. Who in the world is like that? Look, look! Aren't they divine?"). He also talked about the memory of seeking out, with Doris Duke, the places in Burma where, he said, the heiress believed she had been a dancer in a previous life. To demonstrate the ''impossibility" of Callas at the height of her fame, he enacted for me—in his living room—the first, tense meeting of Callas and Pasolini in the singer's Paris apartment, when Rossellini had originally proposed they all make a film together. He was feeble that day, and wheezing, but he stood up in order to mime all of the parts.

''She used to do a production of everything. So Pier Paolo and I arrived for lunch, and then the butler comes in, and then another man. ... This is a huge living room on the Avenue Montaigne. . . and then the personal maid. [Speaking in the moment, as Franco:] 'Bruna, you know this is Mr. Pasolini.' 'Madame is almost ready. Please have a drink.' 'Thank you.' 'I send Ferruccio' [Callas's butler]. .. . Then another one comes, three, four, five people come. And then one little dog. Just walks in. Then Ferruccio comes, saying, 'Madame is going to be here in five minutes.' No way. We sat down. Then.

Continued on page 183

Continued from page 159

Here he was interrupted, to his extravagant annoyance, by the phone. "Andso.. . I used to be on the Avenue Montaigne... No, it was the Rue Georges Mandel.. .Then, finally, three-quarters of an hour of dogs coming in and butlers and waiters... and finally a maid with two dogs arrives. And she looks around. 'Madame is going to sit there.' And then she puts the dogs there. And then 'No, the light is not good, the light is not good.' She gets very nervous. She looks around again. . . . And she takes the dogs and 'There! There!' And after five minutes, you hear the voice—only the voice—[calling the names of her dogs] 'Djedda! Pixie!' And all the staff goes [whispered], 'She'scoming.. . she's arriving.. . ' " Rossellini left the room and returned blinking myopically, with his hands clasped shyly and his face creased into an expression of exaggerated coquetry—the diva incarnate. "Now," he asked grandly, "what do you think of Callas?" He broke into a fit of coughing and was forced to sit down. When he recovered, he looked up at me and said in a grave rasp of a voice, "Do you think I'm going to die?"

The question was one he was reluctant to address. He was, as a rule, cheerfully ambiguous about his medical status, saying he wasn't even sure he was suffering from full-blown AIDS. Friends of his told me it had taken him months to admit publicly he had it, although when he did, it became as essential a part of his persona as the trailing capes he wore in the evening. He embraced the fact in the only manner his native armor of frivolity would allow, heralding the news at dinner parties where AIDS was not a common subject, and always insisting that he was on the verge of being miraculously cured. "Darling, I'm fine. I have a little touch of AIDS, but I'm fine," he would tell people on the phone, as though the disease were a sunburn acquired in Sardinia. At other times, Isabella Rossellini remembered, he would go through periods of "complete exuberance, where he would go jumping in the streets, telling every doorman he passed, 'I have AIDS! I have AIDS!' " He would discuss, with pained empathy, friends with the same affliction; describing one of them, Rudolf Nureyev, he paused to draw for me what he believed was an essential distinction: "He is dying. I am not."

TTVanco Rossellini would often tell me A that his getting AIDS seemed a logical climax to a life lived in extremis and according to impulse. "I wake up in the morning and I jump out of the window, hoping somebody catches me. Like that. That's my life." In that, he said, "I behave exactly like my uncle Roberto." And when he spoke of the watersheds in his uncle's life, it was in a collective voice, as if Franco, too, had somehow contributed to these things. "He sees ourselves very much as a dynasty lately," said Isabella a month before he died. "He always saw that a little bit— it's part of his grand thing. Lately, a lot. He seems to find a sign of supernatural consolation."

His father, Renzo Rossellini, was a composer of film scores—many of them for his brother's movies—operas, and symphonies. He died in 1982 in Monte Carlo, where he maintained close ties to the royal family and was honorary president of the orchestra. Franco's mother, bom Lina Pugni, was a Swiss-Italian concert pianist who worked in the New York offices of the Gucci fashion house from 1971 until 1991 and lived a few blocks away from her only child.

Franco grew up in the Rome of Mussolini and World War II, subjects he seldom seemed to perceive as relevant in discussing his past. He described himself as a shy boy, who would blush whenever he entered an inhabited room, and claimed he was mostly autodidactic, although he attended secondary school in Switzerland. ("My dear, you don't know what kind of a school is that: billionaires sitting down, and we ski.") His parents divorced when he was 14, and he largely kept a distance from his father, a reserved, decorous man, who wanted his son to have a university education and enter the Italian diplomatic corps. "If I see him pass by, I don't know who he is," said Franco of his father. "I never saw him."

His uncle Roberto was another breed— "the lion, the roarer," as Isabella described her father. "He was the one that everybody bowed to." Franco always insisted that his ties to his uncle were singular, and no one today disputes the closeness of the uncle and nephew, or how much they came to resemble each other temperamentally, in their volatility, their impulsiveness, their generosity, and their financial heedlessness. Isabella Rossellini recently speculated that her father's influence may, in some ways, have been dangerous: "I think there was a tremendous pressure on the boys, especially, to match the figure that my father was. . .by taking risks and all that. But I think sometimes Franco paid for them very dearly."

Franco instinctively followed Roberto and his aunt Ingrid into film, working as an assistant on many of his uncle's productions, in both Europe and India. Roberto also got him a job on Francois Truffaut's The 400 Blows (1959) in Paris. Bergman—a woman he described as "somebody you need a long time to understand, because she was scared of everything"—was doing Tea and Sympathy onstage there, and he developed a closeness with her which would endure as a paradigm for his other relationships with formidable women.

Rossellini would also assist Jean-Luc Godard on 1963's Contempt. But he was dismissive of his work with the pioneers of the nouvelle vague, offering only that he was in charge of shepherding the actors in The 400 Blows by subway to the location and that he was always losing the film's star, 15-year-old Jean-Pierre Leaud. He assumed the movie would be a disaster. "Actually, I thought Truffaut had no talent at all because, you know, I have no sense of values, in a way."

Many people wondered why Rossellini didn't become an actor. I saw him in the one film appearance he admitted to, in Federico Fellini's La Dolce Vita (1959). He was on-screen, in one of the movie's centerpiece party scenes, for less than a minute, but he cut an incisive image: dressed in riding clothes, he was startlingly handsome, in a lean, patrician way, and he exuded a haughty, self-contained languor. The director Paul Morrissey recalled Ettore Scola's telling him, "Myself and every other Italian film director have been wishing Franco would be in their films for the last 30 years. He doesn't want to do it." Morrissey continued, "Franco, who basically was very frivolous, had this other kind of perverse, serious side that said, I'm not going to be a performer or I'll never be taken seriously as a producer."

So by the mid-60s, Franco was helming films himself. At 27, with money put up by a wealthy socialite friend, he directed his first movie, The Lady of the Lake, with Vima Lisi, and began producing a year later with Django, a spaghetti Western which starred Rossellini's chauffeur, who was renamed Franco Nero and became a star. In 1966, he began his collaboration with Pasolini. Two of their films—the sexually polymorphous fable Teorema (1968) and a bawdy adaptation of Boccaccio's The Decameron (1970)— drew the censure of both the Catholic Church and the Italian government, which tried Pasolini and Rossellini on charges of obscenity. (The charges were later dismissed.) Rossellini achieved enhanced notoriety and stature as a producer, a role he relished. "He had a period of tremendous glory," said Isabella Rossellini. "And Franco was very grand about it, playing the Hollywood producer with big villas and bodyguards and big cars."

His role in films seemed largely to resemble the one he assumed in his social life: arbitrating, with his own pyrotechnic version of diplomacy, with the "monsters." Working with Pasolini was particularly tense and complicated. "He gave me more problems," Rossellini said happily, adding that they were usually generated by the director's fondness for working-class boys. He counted Pasolini's sexual encounters on a one-week trip the two men took through North Africa: 89. But Pasolini's day-to-day, improvisational style seemed to match Rossellini's own. When Pasolini was bludgeoned to death by a 17-year-old boy in 1975, Rossellini said, it resoundingly marked the end of a chapter in his life. "After the assassination of Pier Paolo, I had like a mental block. I didn't know what to do anymore." He moved to New York—into the modest apartment he would keep until he died—and began to fear for his own safety. He kept at least one bodyguard with him until the end of his life.

The most enduring of these was Enzo Natale, whom Rossellini met on location for The Decameron in Southern Italy, where the 19-year-old Natale was working as a policeman in an anti-Mafia force. Though he had a young son, he left the force to join Rossellini. "Wherever was Franco was Enzo," he told me in his stillfractured English. (His employment was interrupted, Natale said, when, in 1975, he shot a man in the foot who had attacked Rossellini and he was sent to jail for three years.) A cocky, handsome man with a bantam's walk and a bull's shoulders, Natale became, said Rossellini, "not like a butler—more like a son." At the time of his death, Rossellini wanted to adopt the younger man. Natale—who accompanied the producer around the world, sharing the same hotel rooms and dining with Rossellini's exalted friends—said the association was "like a God gift. Really, without wanting it; it was not the plan of my life. It just came like this. From Franco. Only from Franco."

"Darling, I'm fine," Franco would say. "I have a little touch of AIDS, but I'm line."

Although many of his friends assumed Natale was Rossellini's lover, Rossellini denied this emphatically. He admitted, however, to a copious and diverse sexual career and, one afternoon, showed me, "like this old queen," photographs of and letters from some of his more celebrated lovers. A few of them were women—a French film star, an Italian and a French countess ("only women of quality"). But although he said at one point he did not consider himself a homosexual ("I prefer the company of men; I have sympathies"), the pictures were largely of men, ranging from hustlers to two fabled orchestra conductors, both now dead.

After the death of Pasolini, Rossellini's career in films was sporadic. He produced a seldom seen movie with Elizabeth Taylor, The Driver's Seat, in 1973, and in 1976 began work on a project which would kill his love for the business—Caligula, a lengthy, star-studded pornographic film set in ancient Rome. Starring Malcolm McDowell, Peter O'Toole, and Sir John Gielgud, the film received scathing reviews but made—according to Rossellini—a lot of money, particularly in its release as a video. Of its earnings, he said, he saw only a few million, and he sued its financial backer, Bob Guccione, the publisher of Penthouse magazine. The court battle—subsidized in part by Doris Duke, whom he had met in the early 70s—was long and particularly ugly. He never won the case, but it became his obsession. He was still talking about it the last time I saw him, 10 days before he died.

After Caligula, Rossellini began spending more and more of his time idly, hanging out at clubs like Studio 54 and squiring lonely rich women around the world. He also, according to friends, became increasingly fond of cocaine, though he insisted he was never addicted. Marina Cicogna sensed a new aimlessness in his life. "He was much better off when he didn't know where the money was coming from," she said. "Franco was somebody who had to create and re-create and reinvent life from day to day. When he met Doris, and he had done Caligula, he suddenly thought he was going to have a lot of money and that money never came through.... And I think that was the worst thing that ever could have happened to him."

He indeed seemed to be struggling to find a new raison d'etre. He helped organize social functions—such as the Museum of Modem Art's Vittorio De Sica retrospective in 1991—and the idea of good works assumed a heightened appeal: in 1985, he toured the drought-stricken countries of Africa with a goodwill ship sponsored by the United Nations. And he found himself developing personal relationships with the homeless people in his neighborhood. "He was incredibly generous with his money," said one friend. "He was also very generous with other people's money."

It seemed, curiously, a point of honor to him to say he did not get AIDS through sexual contact. The stories of how he believed he did contract it were numerous and contradictory. The most common involved his becoming infected during either a United Nations visit to an African leper colony or a Moroccan pedicure. Equally confusing were his accounts of discovering that he actually had AIDS—I remain unsure -as to whether he learned this in a hospital in Florence, Paris, or New York—but it was precipitated by a severe infection which consumed his left foot following an accident (he either fell off a horse in Argentina, which is what he told me, or stepped on a mine in Beirut, which is what he said to Isabella). But when he checked into Cabrini in June 1991, he was desperately ill.

Isabella Rossellini remembered visiting him in the hospital at that time. "It was a very touching experience of holding somebody's hands and going, slowly, at his pace, to recognizing that he had AIDS. And he was incredible. He would say one moment that he had it, and then I could see the desperation overwhelming him, and he would go back to his fantasy of glory, talking about my mother, and then say, 'I don't know what I have in my foot,' and completely deny what we d got to five minutes before. And I stayed hours and hours and hours and hours. And little by little by little by little, he faced it. And he started to cry.... And I perceived a kind of a relief in him once he was admitting it. And we talked about death. And he was surprised that he wasn't afraid of it. And he talked about dead friends—Maria Callas and others—and he talked about his life; he said, 'I have had such a beautiful life, I have such wonderful friends.' And I thought, This is Franco at his best—to see someone so compassionate and accepting and all that."

Around that time, Isabella said, Rossellini was also visited by a priest, who mentioned the name of a bishop who had been treated at the same hospital. "And Franco said, 'Oh, really, but you know, he has been my lover. He's a nice man.' I mean, to the priest. He turned white, I almost passed out, and I thought, Well, enjoy the ride, Father. Here is a soul to be saved. It's a challenge for you. What can I say?"

In the last year of his life, Rossellini was in and out of the hospital, but he still managed to fly to the Philippines and to Europe—where he said he was attending to his suit against Guccione—and he would occasionally even rise from his hospital bed to attend a party, if it seemed important enough. He never divorced himself spiritually from the glittering world he had once moved in. The aggrandizing charm was always on tap. And he never stopped dropping names; they were, after all, what he thought defined him. One day when I visited him at Cabrini, he told me he had just received a telephone call from Jonas Salk, who had been a friend of his father's and who reported he was making progress on a cure for AIDS. "It is not everyone who has a Nobel Prize winner to call him," he said. (Although, in fact, Salk never won the prize.) I told him I had been reading Enzo Siciliano's biography of Pasolini. "I know it," he said sadly. "Iam not in it."

He kept a running tally of who had called him, who had visited, who had sent flowers. Those who had paid him attention were described adoringly; the others were skewered mercilessly in his anecdotes. Enzo Natale was usually at the hospital, as was Rossellini's mother, a straight-backed octogenarian who arrived every day in a crisp suit or dress and tiers of pearls. He delighted in baiting his mother, dropping salacious bits about his and other people's sexual histories or discussing his use of cocaine. She would stiffen in her seat and shrug. "I did not know about these things before now," she once responded. ''There were many things I did not know." His dramatic timing remained impeccable, and when I left the hospital one day, he raised one hand in the air and whispered, ''Don't forget me."

The last time I saw him, on May 23, he had briefly returned to his apartment. I had gone there to talk to Natale and Lina Rossellini, and I hadn't expected to see him. But he made an unforgettable entrance—steeled, he said, by two Percodans—from his bedroom, on the broad arm of a nurse he had hired, wearing a monogrammed white terry-cloth robe and dark glasses. As Natale talked about his years with Franco, Rossellini would interrupt chirpily to discuss a project which he seemed to feel would ensure his lasting fame, a biography of the Rossellinis: "You see how many Rossellini books there are. But nobody has our story." He wanted to know if I had read the new book on Doris Duke, by Stephanie Mansfield. "I'm dying to read the book of Stephanie," he said. "I wonder what they say about me. They decided I'm a hustler? Because a hustler I'm not." It was my last conversation with him. He died, in Cabrini, early in the morning on June 3.

T wasn't a witness to the event which X inspired my favorite story about Franco Rossellini. It occurred in early April 1992, at a party at the Museum of Modem Art, commemorating the 50th anniversary of the film Casablanca, in which his aunt Ingrid had starred. Rossellini had helped organize the guest list for it, and even though he was in the hospital then, he was determined to attend. Isabella Rossellini suggested he use a wheelchair, although his doctor said he didn't require one. "I could see his eyes flashing," she said, "not because it was a good idea, but out of vanity, like, Ah, what a wonderful entrance... He arrived. My [half-] sister Pia [Lindstrom, also a daughter of Ingrid Bergman] talked [to the audience] about Casablanca and talked about the people who were there, and mentioned Franco. Franco got a huge applause; we don't know why, because he had no connection with Casablanca. But he made that evening— he made that entrance, and with the theatricality of it, people felt he was a survivor of Casablanca. In the confusion of its 50th year, he got the standing ovation."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now