Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

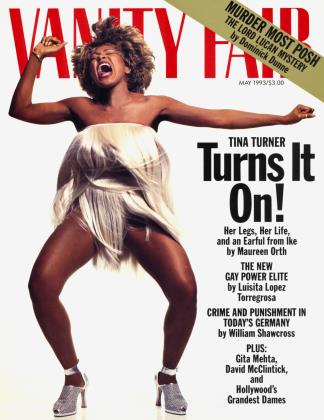

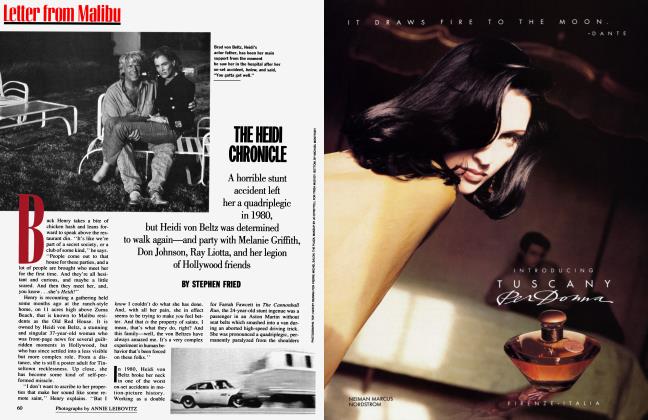

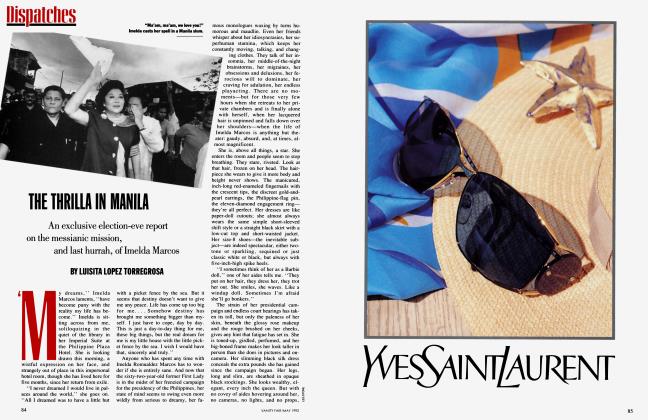

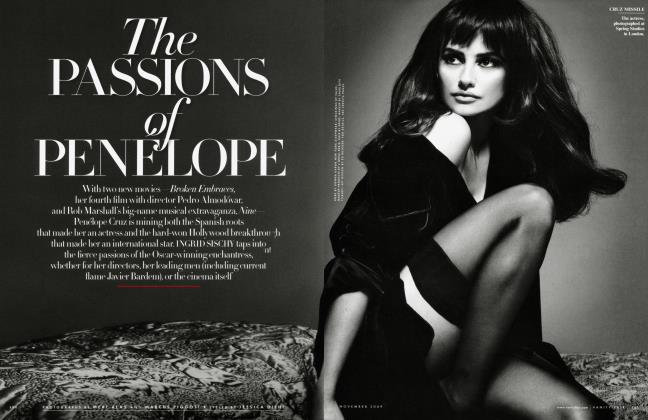

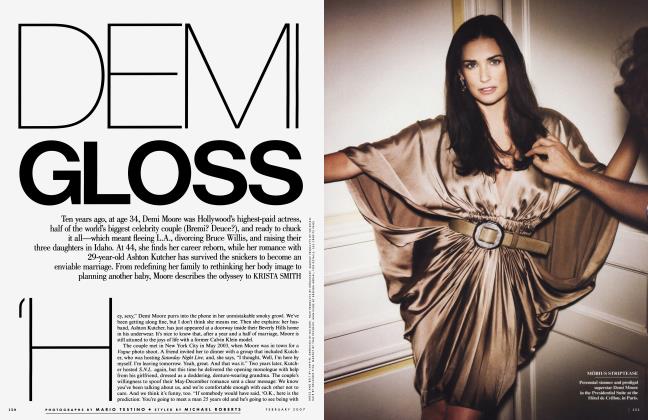

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOn April 25, as many as one million people will march on Washington, D.C., in what gay leaders hope will be the defining moment of the emerging civil-rights movement of the 1990s. LUISITA LOPEZ TORREGROSA goes inside the new gay-and-lesbian power structure to chart the behind-the-scenes leadership struggle and gauge the competing strategies for the battle ahead

May 1993 Luisita Lopez Torregrosa James Hamilton, Helmut NewtonOn April 25, as many as one million people will march on Washington, D.C., in what gay leaders hope will be the defining moment of the emerging civil-rights movement of the 1990s. LUISITA LOPEZ TORREGROSA goes inside the new gay-and-lesbian power structure to chart the behind-the-scenes leadership struggle and gauge the competing strategies for the battle ahead

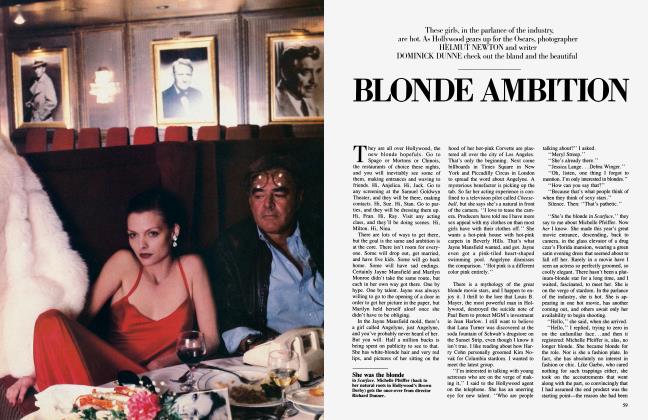

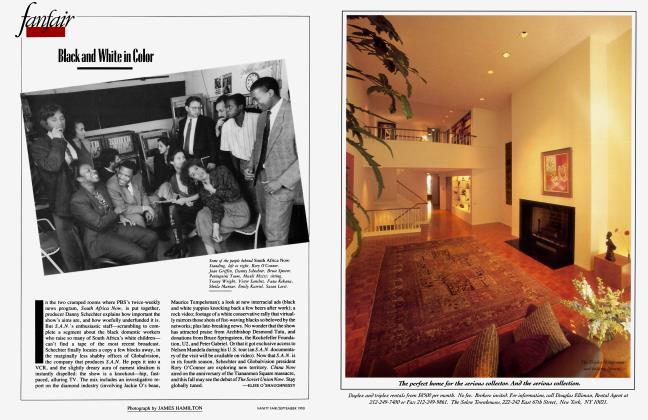

May 1993 Luisita Lopez Torregrosa James Hamilton, Helmut NewtonWe are up in the Hollywood Hills, that familiar backdrop of America's adolescent fantasies, of countless reels of lusty teenagers in hot-rod convertibles and drunken lovers hurling bottles into the void of the Los Angeles basin. We have come up here, to this sprawling white bungalow, with its bleached wood floors and pale hues of tans and beiges, for a strategy session of ANGLE (Access Now for Gay and Lesbian Equality), the new avant-garde of the gay-and-lesbian movement, an exclusive group of some 18 high-powered L.A. lawyers, doctors, publicists, and corporate executives joined in a fierce, single-minded crusade to win full equality for gays and lesbians in the 1990s. Squeezed into a comer of a sofa, showered with kisses and bear hugs by his longtime friends, sits ANGLE's most prominent member, David B. Mixner, who has come to power as the gay political strategist who brought together candidate Bill Clinton and America's gay-and-lesbian community.

The group, an upbeat clique of ambitious, affluent high-achievers in designer clothes, are drinking Diet Coke and trading inside jokes. Someone brings in a huge poster of Marky Mark, which causes a round of laughter and wry comments. But once the meeting begins, everyone is serious and focused, all business. There is a tactical discussion about an upcoming fund-raiser for a friendly U.S. Senate incumbent—which big name can they get to host it, and should it be $250 or $1,000 per plate? Next on the agenda: discussing who will mastermind the April 25 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights, the first major gay demonstration in the capital in almost six years. Someone suggests Sky Johnson, who choreographed events at the Democratic National Convention.

The hottest debate centers on the 1994 elections. ANGLE, which took a risky position by endorsing Bill Clinton in October 1991—more than three months before the New Hampshire primary—is already zeroing in on the California Democratic gubernatorial primary, almost a year and a half away. Although everyone agrees the hands-down winner will be Kathleen Brown, California's treasurer and the younger sister of former governor Jerry Brown, some members feel loyalty to John Garamendi, a dark-horse candidate who has been a longtime friend of the gay community.

Two of the women speak passionately for Brown, who has been paying increasing attention to the powerful gay community (she recently hired a lesbian as a senior aide). A few others feel the group should delay an endorsement, dangling it in front of Brown to gain further commitments. The meeting, which is contentious by ANGLE standards, ends in a vote to endorse Brown now. "It was the smart choice," says Diane Abbitt, a corporate lawyer and a founder of the group.

The decision, which will give ANGLE an inside track in the likely Brown administration, is the sort of hard-nosed, realpolitik move that makes this the vanguard group in the mainstreaming of gay America. "The gay community is no longer a fringe, special-interest group," Mixner often declares. "We are a civil-rights movement."

After 12 years in the wilderness—years marked by the AIDS epidemic and the hostility of two Republican administrations—gays are fighting to seize the high ground and forge a moral crusade that will not be turned back. During the 1980s, a growing number of activists, contributors, and sympathizers, moved by AIDS and pushed by direct-action groups such as ACT UP, fought scattered and often losing battles. But when the major Democratic presidential candidates declared their support for gays in the 1992 primaries, the community gathered force, metamorphosing into a politically, savvy, image-conscious, mainstream-friendly, multimillion-dollar campaign to win over America.

"The movement I work in might be called a gay- and-lesbian movement, but its mission is the liberation of all people."

Beneath the sweeping fervor and newfound success, however, a struggle for the soul of the movement is taking place. Like the freedom fighters of the 60s, the gay and lesbian leaders are reaching out for one overarching goal: to be able to sit in the front of the bus. But they differ on the question of how to get there—and who will lead them. "We are a diverse community," gays and lesbians never tire of saying. "No one or two people can represent us." This laudable attitude has left the community with many local heroes but no predominant national leader, no gay Martin Luther King Jr. to stir up the passions of the crowds and reach out to mainstream America. "Gays have the opportunity now," says the writer Larry Kramer, the founder of ACT UP. "We have the foot in the door but not a body to go with it. We don't have the muscle. There's not one gay leader to present our point of view." Admitting that the days of ACT UP activism have passed, Kramer says, "We need a powerhouse organization in Washington, but they are all wimps and they don't even get along with each other. Where is our Jesse Jackson? Where is our Gloria Steinem? Where is our Martin Luther King Jr.?"

With his access to the White House and his sudden appearance in the national spotlight, David Mixner would seem to be the best candidate, the undisputed leader of the latest wave in the gay movement. A veteran of the antiwar marches and numerous political campaigns, the 250-pound activist is also a strategic planner for some of the largest corporations in the country. (Careful to keep his professional lives separate, he asks that the companies not be identified.) He is so well respected within the gay community and in the Democratic Party establishment that the Gay and Lesbian Victory Fund party in his honor during inauguration week was one of the hottest tickets in town.

At his best, Mixner is a stirring speaker and a solicitous friend, a wise, smiling buddha. But there is also a certain coldness of eye, a manipulative, chairman-of-the-board attitude and ambition that intimidate and even anger other gay leaders. "David is dangerous," says a lesbian leader who works closely with him. "He's out for himself and he tramples everyone else." Even Mixner admits, "My greatest enemy is my ego. I used to try to do everything from the top down. I tried to set the agenda. I made mistakes."

His source of power is his access to the White House, a connection that makes him indispensable to colleagues and rivals. But he isn't the only contender for the mantle of leadership of the gay movement. Other activists with major influence include firebrand Urvashi Vaid, the former head of the National Gay & Lesbian Task Force, who hopes to build a grass-roots movement from coast to coast; Hilary B. Rosen, a recording-industry executive in Washington, who is on the A list of gay power brokers and whose network reaches into the mainstream establishment. And Patricia Ireland, the charismatic president of the National Organization for Women, a tenacious feminist who wants to bridge the women's and lesbian-and-gay movements.

These leaders are now marshaling their resources for the current battle in Congress over the military ban on gays and lesbians, where the mettle of the movement will be tested in a clash against real-life generals and an army of conservatives. The fight will be waged in Senate and House hearing rooms and Capitol Hill offices, in Washington restaurants and statehouse cloakrooms, and on Good Morning America and Nightline, where many Americans will see and hear some of these gay advocates for the first time.

On the gay side of the line stands the fragile coalition of rights groups stitched together by Mixner and a handful of topranking leaders that is organizing the multimillion-dollar lobbying-and-media effort called the Campaign for Military Service. "It's a paradox for me," Mixner says. "All my life I've been a pacifist, a follower of Gandhi and King, and now I'm embroiled in this fight to allow my people to go to war. But it is more than that. It is a fight for our own liberation."

The fight, he knows, will be furious. The gay leadership was shocked by the fire storm of antigay sentiment that engulfed the White House in January after it was leaked that the president intended to sign an executive order reversing the ban. President Clinton's retreat, a hasty decision to postpone lifting the ban until July 15, may have dismayed some gays, but it did not soften their support for the president. Instead, they all agree, it jolted them from their inaugural euphoria and reminded them that their ally in the White House could not, and would not, fight this battle all alone.

"The gay movement is in vogue. Now that the press is on our side, more people are coming in. This is the thing of the 90s."

Amid the furor in Washington, the impatient Mixner led the charge at an ANGLE meeting on January 27. The meeting was, as usual, held in private. But participants that evening told me the group was in a rage, lambasting the Washington-based gay organizations for responding to the anti-gay onslaught too timidly and too late. They decided something had to be done quickly to grab the reins of the movement from the old Washington hands.

Days after the ANGLE meeting, about two dozen organizers and financiers gathered at two secretive meetings in Georgetown, at the home of Robert Shrum, a political consultant who, with his wife, Marylouise Oates, is among the most active straight supporters of the gay community. The gatherings, kept under wraps from the press and even from some officials of gay organizations, included Mixner and the directors of gay-establishment groups such as the Human Rights Campaign Fund and the National Gay & Lesbian Task Force. But the most high-profile guests came from outside: the president of a powerful feminist fund-raising group, who does not want to be identified; Barry Diller, the entertainment mogul; and Bob Burkett, a spokesman for music-industry tycoon David Geffen. "I walked in there," one participant confides, "and I was stunned at the caliber of the people I saw."

With seed money from Geffen, Diller, and financiers from San Francisco, New York, and Omaha, a coalition was formed to create the Campaign for Military Service, with its own headquarters in the capital and its own director, Thomas B. Stoddard, a New York attorney and former head of the Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund. The mission: to raise some $4 million, and, more important, to reshape and redefine the lesbian-and-gay movement itself.

But the lines of authority were blurred and control over money unclear. A rumble of protest soon exploded, coming mainly but not solely from activists who felt shut out. They suspected a Hollywood-Washington cabal, led by Mixner and Stoddard, who were seen as a pair of megalomaniacs out to stage a coup to displace the old workhorses of the movement, the unglamorous and underfinanced organizations whose labors have gone largely unappreciated by the mainstream media and by the new, high-flying types—"20 rich boys with checkbooks," as a wary longtime activist put it.

The mini-revolt broke into the open in the sunshine lull of Palm Springs, where the Human Rights Campaign Fund's directors and governors gathered one weekend in mid-February for their twice-yearly meeting, which I attended at their invitation. "Our organization is getting bounced around by a maverick bunch," said a prominent member, who lashed out during one of the most heated sessions. "If David and Tom Stoddard try to come in as messiahs," another participant cautioned darkly, "we should not buy into it."

Within days of the Palm Springs powwow, half a dozen headstrong potentates of the movement met over breakfast at the Four Seasons Hotel in Washington and papered over their differences with Mixner and Stoddard. Back in L.A., Mixner fended off suggestions that the Campaign for Military Service was his baby, and dismissed the contretemps as politics-as-usual. "If there's anything that proves we're the same as nongay groups," he says, "it's this sort of pull-and-tug. It's no different than any other campaign I've been involved in, gay or nongay. When you put together a diverse coalition, it takes a while to hammer it out, shake it out."

"Washington is an insiders' town, and access to power is very seductive. That's happening now with the gay movement."

It's ironic, though perhaps inevitable, that the power plays and sometimes vicious infighting are coming at the time of the movement's greatest influence. Gay and lesbian leaders claim that the gay community provided seven million votes for Bill Clinton, although other estimates are lower. Now, with a supportive president in the White House and an influx of openly gay people in the corridors of power in Washington, prosperous gays are climbing on board and contributions are pouring in.

The march on Washington on April 25 is envisioned as "the defining moment of the movement,'' as significant as the 1963 civil-rights march led by Martin Luther King Jr. "We have no room for mistakes," Mixner says. "The march is critical to the community and crucial to the vote on the ban." A million lesbians, gays, bisexuals, and their friends, families, and supporters are expected to turn out in what organizers hope will be the largest civil-rights march ever in Washington. Already, every hotel and motel room in the area has been booked; the overflow will stay in churches, community centers, and private homes.

In the ebullient spirit of President Clinton's inauguration week, gay leaders have called on Hollywood producers to give sizzle to the show. Chartered planes will bring in Hollywood and Broadway stars such as Richard Gere and Cindy Crawford, Dustin Hoffman, Susan Sarandon and Tim Robbins, and Cybill Shepherd. Celebrants will be caught up in a whirl of more than 230 events, from a Texas two-step party to an exclusive $ 1,000-a-plate dinner for the Victory Fund and the Robert Mapplethorpe Laboratory for AIDS Research. Just about every major liberal organization and subgroup wants a role to play, from gay and lesbian veterans' groups to the N.A.A.C.P., which for the first time ever has endorsed a gay march.

"The gay movement is in vogue," activist Hilary Rosen says. "There have been a hell of a lot of people who have not used their own situations on behalf of the gay communities. Others have taken the shit. Now that the press is on our side, more people are coming in. This is the thing of the 90s."

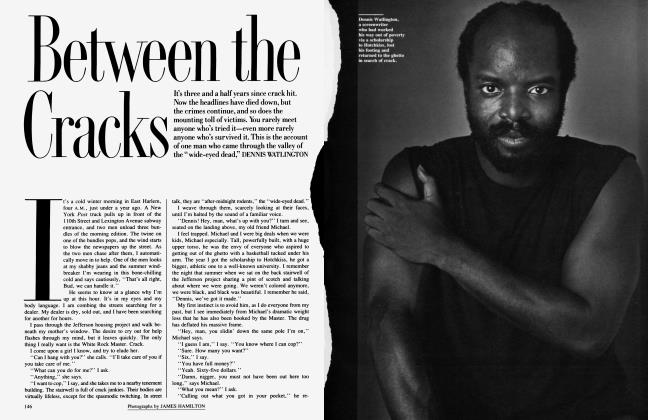

I meet David Mixner on a freezing early morning in Washington, at the Four Seasons Hotel, where he usually stays. I am struck by his size—six feet one but taller in two-inch-high black boots, big-boned, beefy. The 46-year-old activist is wearing a dark-blue suit and is bundled up in a scarf and a heavy navy-blue wool overcoat. Briefcase in hand, he looks every bit the businessman strolling down the Four Seasons lobby.

We take a cab to Cafe Luna, a hangout in the Dupont Circle area, for a private meeting with three organizers of the April 25 march, earnest grass-roots types in T-shirts and punky haircuts. Over coffee and bagels, Mixner and William Waybourn, the 45-year-old executive director of the Victory Fund, are painstakingly solicitous of the "kids," who seem to be, frankly, in over their heads. Mixner tries on a fatherly manner and steps lightly. "Any way my name is useful, use it," he tells them. "If harmful, don't." Though everyone is eager to see the march succeed, there's no obvious meeting of minds.

"I give suggestions. I give help," Mixner observes later. "But if I had injected myself, that whole meeting would have been about me positioning myself, and no one would have listened to me."

A week later, I watch Mixner use the same paternal diplomacy on the phone in his office in West Hollywood, on the second floor of his $l,700-a-month apartment, where he lives alone with his three cats. "These activists don't want to feel out of the loop," he counsels a ruffled gay leader in Washington, who, like many in the top layers of the gay establishment, calls Mixner almost every day. "So you have to make these people feel important. Bring them in."

On the office walls around him hangs the story of his life, framed photographs and newspaper clippings, mementos and peace posters—Bill Clinton and David, Hillary and David, Ted Kennedy and David, Jimmy Carter and David. There's a telegram from Bill Clinton, dated May 20, 1992, that says, "Let's wrap things up soon." There's a copy of Clinton's address to gays and lesbians at the Palace theater in L.A., the "I have a vision, and you are a part of it" speech, which is now inscribed on plaques in dozens of offices from Hollywood to Washington.

At home, Mixner drops the corporate mien he wears along with pin-striped suits and suspenders when he visits Washington. He sorts through the stack of mail, and pays immediate attention to a white envelope, a letter from the White House. Although he does not like to boast about it, Mixner, who was a senior adviser in Bill Clinton's national campaign, is in regular contact with the staffs of the president and Hillary Rodham Clinton. He often goes to the White House, and letters, phone calls, and faxes flow back and forth.

Mixner's recent access to power is not the most important distinction between his position today and his activist roots. "I think a major difference in my life between now and the 60s and 70s, when I was in the anti-war movement and the civil-rights movement," he says, "is that then I was always fighting for someone else's rights, and at the same time in great personal pain about being in the closet. But now I'm fighting for my own freedom. It is giving me a dignity and a self-esteem that I've never known in my life. I don't feel that anyone can kick me around anymore, that they can lie about me anymore."

But it is not only a personal crusade. "I am doing this for our young," he says, "so they won't have to go through what we've been through. They robbed us of our dreams. There were so many who wanted to be a congressman, or a corporate leader, but they knew they couldn't because they were gay. It was a crime."

That is why today, he says in his raspy voice, "I am a militant believer in people coming out of the closet. I think it's our ultimate weapon. It is imperative that we not only come out but that we not turn ourselves away from any normal daily activity that is accepted behavior in the heterosexual community. The moment we do that, we become less."

David Benjamin Mixner, the youngest of three children in a working-class family from Elmer, New Jersey, a dropout from Arizona State University, a lifetime activist, and now a recovering alcoholic, was 30 years old when he came out of the closet. But he had lived with his pain since he was a boy, he tells me over a lunch he barely touches at the Aux Beaux Champs restaurant at the Four Seasons, back in Washington. "I've known I was gay since I was six or seven. The remarkable thing to me is not only that I knew it, but how we have this wisdom. I knew I couldn't tell anybody. I knew it was something I couldn't mention to another soul. And it made me feel different and apart from my family and my friends. I think each of our journeys through this is in many ways different. I felt extraordinarily lonely, isolated, and that something was wrong with me."

He was 17, at Arizona State, when he first fell in love, with a player on the football team. Soon, they became roommates. "It was for me," he says with tears in his eyes, "a very powerful love story. But nine months after we met he died in an automobile accident. I was convinced the reason he died was because of what we had done. That this was a punishment."

For years afterward, Mixner did not allow intimacy, indulging only in casual encounters where he lied about his name and numbed himself with alcohol and drugs, all along terrified that his activist career would be destroyed if he were found out. It was during that long period that he would tell friends and colleagues that he had once been engaged to a girl who died in an accident—the story he told Bill Clinton when they first met, at a Eugene McCarthy campaign reunion on Martha's Vineyard in 1969. Mixner finally decided to come out after he met a California businessman and gay organizer named Peter Scott, who would become his best friend and business partner in a relationship that lasted 12 years, until Scott's death from AIDS in 1989.

"Except for the little fact of homosexuality, gay men would be just like straight men."

"The other reason I came out was Anita Bryant," Mixner recalls with a bitter smile. "She was launching a campaign of hate in South Florida in 1977, and I could no longer justify to myself that I was working for everyone else's freedom but not my own. That's when I came out to my family and friends. And it was a horrible experience. The first thing that happened was that most of my friends immediately forgot that I had any other skills—all I was was gay. It was difficult for my mother and father, but I had made up my mind that it took me 30 years to be comfortable with myself and I couldn't expect them to do it in 30 seconds." He sent letters to all of his friends in politics, more than 300 letters, revealing he was gay and asking for money to fight Anita Bryant. "I lost many friends," he laments. "They disappeared from my life, or treated me differently. There were nights when I cried, I was so scared and alone."

Among those who did not turn away were Bill and Hillary Clinton, whom Mixner had met separately, before they married. "For almost 10 years Bill and I had been pretty close. We had similar backgrounds; we grew up in small villages. We both had marvelous dreams of what this nation could be."

It was natural, then, when Mixner decided to come out that he would phone the Clintons in Arkansas. The conversation was not long, but he remembers their warmth. Then, in 1981, the governor called him and asked him to arrange a reception in Los Angeles. "In a gesture that I will never forget," Mixner says, his voice shaking, "he asked Peter Scott and me to host the reception at Peter's house. There was no question in my mind that not only was this his way of telling me that he viewed me as the same person he once knew but that he was making a statement to everybody else. It's something I'll never forget."

Then came the phone call, on September 19, 1991, that sealed their friendship. "The governor asked me if I would help with his presidential campaign," says Mixner. "We talked about the potential emerging power of the gay-and-lesbian community as a political force, and he asked me to set up a meeting with my friends at ANGLE." A quiet gathering, on the evening of October 14, 1991, was arranged at the house of a 34-year-old ANGLE founder, Dr. Scott Hitt, the same place I had visited in the Hollywood Hills. In that living room, with its expensive pearl-white leather couches and panoramic view of Los Angeles, an emotional pact was forged between the governor and the major players of the gay community in Southern California.

But it was Hillary Clinton who broke the ice, warming up the wary listeners with words of understanding. The Clintons, Mixner tells me, had other gay friends, and Mrs. Clinton knew firsthand the pain of losing one to AIDS—Dan Bradley, former president of the Legal Services Corporation, who died in 1988. "Most of the people going into that October meeting were for Paul Tsongas or Jerry Brown," Mixner recalls. "I had to really convince people to come. There were about 20 of us. But Bill Clinton was incredible. I've not seen anything like that since Bobby Kennedy used to go into minority communities and immediately identified emotionally. It was a spiritual bond. This man, we felt, knew about our journey.

"That day he told the Los Angeles Times that if he were governor of California he would have signed the gay-rights bill that Pete Wilson had just vetoed. That was it! Suddenly 20 people became fanatic Clinton supporters, and that was the nucleus for the whole nation."

It is just this kind of talk that riles Urvashi Vaid, a 34-year-old iconoclast whose style has more in common with the militant 70s than with the boomer 90s. A purist ideologue, she's a perfect candidate for burnout after a decade of infighting and fund-raising and grass-roots organizing. But when she stepped down as head of the National Gay & Lesbian Task Force late last year, she was not running away but simply shifting her battleground.

She moved to Provincetown, Massachusetts, a gay haven, to clear her head of the Beltway babble, to put her Gandhian vision of social justice into a book, and to recharge her spirit for her next great mission, building a nationwide movement for freedom and equality. And, she'll tell you proudly, she also moved to Provincetown to keep house with her lover of five years, the comedian Kate Clinton, from whom she had always lived apart because their jobs kept them both on the road.

She is stopping over in Washington on her way back from giving a speech at Duke University when I catch up with her. She wears her battle scars on her face, tiny lines around her eyes and down her mouth, and a deep frown. We are meeting at the Jefferson Hotel, four blocks from the White House. She grabs my hand and her clasp is strong, but she is small, a dark-haired sprite, and a bit shy in these plush surroundings. Heads turn as we walk into the restaurant, and waiters and hotel staffers come by to shake her hand—"She's done so much for the movement," one tells me. A vegetarian, she is finicky about traces of shellfish in her soup, which she does not finish in any case because she is too busy talking.

"The movement I work in might be called a gay-and-lesbian movement, but its mission is the liberation of all people," she declares. "To me my mission is about ending sexism, about ending racism, and about ending homophobia." She doesn't seem to see anything grandiose about any of it and speaks in torrents, in perfectly crafted sentences sprayed with Washingtonese, two-ton words like "infrastructure" and "strategizing," and I have to wonder how she can throw those words at a crowd and inflame their hearts. But I have been told that she does, that she's the single visionary and global thinker of the movement, its Pasionaria.

For hours afterward she remains focused, attentive, and invariably affable, whether driving from the Jefferson to the spare offices of the Campaign for Military Service on Embassy Row or sitting in the noisy bar where she is meeting Fred Hochberg, a wealthy 41-year-old Manhattan mail-order-business heir. Sitting across from each other, Hochberg and Vaid are a picture of contrasts, representing the two major and rival strands of the movement: the grass-roots organizer in baggy black pants and black sweater, and the businessman in a navy blazer and tailored charcoal-gray pants.

"I am not an inside-the-Beltway person," she tells me later. "My idea of power is very democratic and ground-up. It's not about a bunch of people running around, making high-level decisions in the back room. I'm not saying this to put anybody down. My colleagues are brilliant men, and I mean men. Ninety percent of the movement at this level are men, and practically all of the people at this level are white.... Feminist issues are off the point to them. They are the dominant culture. Except for the little fact of homosexuality, gay men would be just like straight men."

Ironically, it is the gay men in the top ranks of the movement who are most effusive about Vaid. "Urvashi is a tremendous symbol, a moving force," says Timothy McFeeley, director of the Human Rights Campaign Fund, a workhorse who has neither the ambition nor the passion he sees in Vaid. "Urvashi is astonishing," Tom Stoddard says, "principled, smart, deeply virtuous. She has a vision of the world." Mixner himself, who is no sentimentalist about his colleagues, says Vaid is extremely talented. Told about her star billing, she laughs and suggests that perhaps "the boys" were saying these things because they were talking to a female reporter. She is not easily fooled and knows she cannot possibly belong to the club. "Boys tend to play either-or politics—'You do it my way or you are an asshole.' That's on the record," she assures me.

It's a measure of her self-confidence—in her lingo, her "centeredness"—that she rarely goes off the record, even on the touchiest issues. She is one of the few major gay leaders who still defend the in-your-face defiance of groups such as ACT UP and Queer Nation. "Though ACT UP has splintered in the big cities, it is still very effective in places like Kansas City and Atlanta. It is inaccurate to say ACT UP has seen its heyday. They still have a role to play, as a channel for gay emotions. You can't just have dispassionate organizations."

Vaid's personal passions were formed early on. She was eight when her parents emigrated from New Delhi to the United States. Even in Potsdam, New York, a small middle-class town where her father taught English literature at the State University of New York, her mother wore saris and cooked only Indian food. "I was a very awkward young girl," Vaid recalls. "I spoke with an Indian accent. I had these very thick glasses. I had long hair, very thick, straight hair, Indian hair, down to my waist. I was such an intellectual. I read voraciously, and by the time I was 12 I was going through my parents' library—Henry James, Thomas Hardy. I lived a lot in my head."

Vaid was also politically precocious: at 11 she joined the town's anti-war marches; at 12 she gave a pro-George McGovern speech. Bored with high school, she graduated in three years, won a scholarship to Vassar, and changed her whole life. "I was 16 when I walked in the door. I was quite innocent and quite earnest and I got immediately involved in campus politics. " These were the feminist and anti-war 70s, the time of sit-down strikes and teach-ins. "There was a women's group on campus, and the women were fabulous, dressed in black from head to toe, just as I am today. Very attractive, and all rumored to be lesbians. To me they were my first role models of what a lesbian looked like, and they were so glamorous."

From her early teens, Vaid knew she was drawn to women, but she dated boys until she was a senior at Vassar, when she fell in love with a French classmate. Their relationship ended when her friend returned to Europe, leaving Vaid crushed and lonely. She moved to Boston, where her life began to revolve entirely around the gay community. She attended Northeastern University School of Law, lived in a lesbian group house, and took a secretarial job at a law firm before working at an alternative weekly. "I was an out lesbian, but I was terrified because of the stigma. I didn't know it would be possible to live my life as a lesbian."

When she finally told her parents, her father was not surprised, saying only, "I thought so." But it was awful for her mother, who to this day has not met Vaid's lover. "I think I would have been a lesbian whether I grew up in India or America," she says. "Eventually I would have found it. This is how I feel about my sexuality. It's very, very deep in me, and it was formed early, and once I could name it and accept it, it became fixed."

It is her sexuality and ethnic identity that inform her approach as a leader. "As a lesbian of color, I can't help but bring more than one identity and more than one issue to the table, and try to lead our movement not just on this narrow issue called homosexuality but on this larger thing called oppression."

We've talked all afternoon by now, and she's worn out at last. But the next day she comes charging in to join me for an early breakfast. "Power comes from the grass roots up," she starts off, fully awake even before the first sip of coffee. "But what's happening today is a very top-down power strategy," she says with obvious disdain. "It's a very pragmatic approach: get people with money, get people with access to political power, to be the brokers for the community.... It's the way the world works. Rise up the corporate ladder, play the sleazy games, talk about making deals and talk about access to power and feel very powerful. And then what?"

She laughs heartily. "I sound like a hippie, don't I?" But she rolls on. "We have money. We have something of a philosophy. But we have no overall design, no infrastructure. We have no strategy for the long term. We go from crisis to crisis.. .. Why is it so hard for us to build? Because of the closet. Because so many of our people are hidden from us. Many women leaders still feel the need to be closeted to protect their access or their status. They feel if they come out of the closet as lesbians in the women's movement they will somehow lose their leadership." Her hand clutches my arm to make sure I get the point. "It's the system, and it affects every part of the history and progress of the gay-and-lesbian civil-rights movement. The closet has shaped us."

I can see now why her admirers believe she can part the waters. Her speech over, she leans back into the banquette, picks up a bran muffin, and slathers it with butter. A waiter comes over to greet her, and she becomes little Urvashi, sweet, gentle, infinitely patient. Then it's over and she rises to go, the breakfast on the house, the restaurant staff virtually applauding.

In a red knit dress and black pumps, her curled hair fluffed, her face made up, moisturized, lipsticked, and mascaraed, Hilary Rosen is the polar opposite of Urvashi Vaid. Calm, reserved, self-absorbed, Rosen, her friends say affectionately, is the model Jewish American princess. She is leading me into her vast, color-coordinated office in the high rise off K Street that houses the Recording Industry Association of America. It's eight o'clock in the morning and the place is dead quiet, the street noise muffled by wall-to-wall carpeting and thick windows.

Rosen offers coffee, closes the door, sits on a sofa with her hands clasped in her lap, and studies me. She is wary, she admits, calibrating her words. She's an expert at spin and damage control, a veteran lobbyist, smart, swift-tongued. Her role is not to stand before crowds and stir up trouble, but rather to calm the waters, pull the strings, get things done. At 34 she's on everyone's shortlist of lesbian Washington power brokers, a political insider and fund-raiser who is also a top executive in the recording business. She enjoys a six-figure salary and a new, half-million-dollar house she bought with her girlfriend in an exclusive Washington neighborhood.

"There are many stars in the movement," she says, deflecting the spotlight from herself. She mentions her friend Roberta Achtenberg, the San Francisco city supervisor nominated as an assistant secretary at the Department of Housing and Urban Development, who has turned down requests for an interview pending her confirmation hearings. But Achtenberg has a problem, several gay leaders confide. She may sink into obscurity in the bureaucracy, eclipsed by the more high-profile Mixners and Vaids. "There's David of course," Rosen continues. "He's riding a wave. That's not to take away from his abilities to get things done. David understands how it all connects." As for Vaid, "She has a message and a place in the movement, but she's not a power player in Washington."

Mixner says Clinton "talked about the emerging power of the gay-and-lesbian community, and he asked me to set up a meeting with ANGLE."

A connoisseur of power, Rosen appreciates its uses and is suspicious of outsiders—people who have not been in the trenches doing the grunt work, newcomers who are arriving late bearing checks and demanding influence. For six years she's been a board member of the Human Rights Campaign Fund, which, with 70,000 members, is the largest gay political organization. Loyal to the core, she can get testy when people suggest that the Campaign Fund and its director, Tim McFeeley, a Harvard Law graduate whom she helped recruit for the $85,000-a-year job, have fallen by the wayside, left behind by the Mixner-led Hollywood blitz. Yet she herself fits comfortably into the new mode. She talks of alignments with African-American and women's groups, of using marketing tools to change the negative image of gays and lesbians, of targeting the media and sitting down with editorial boards. Working in the music industry gives her access to and know-how of the show biz of politics and the politics of show biz. "Hilary has a great power network," a gay leader who has had run-ins with her tells me. "She understands strategy, the mainstream, and money, and she's loyal and personable. She's one of the great leaders of the future."

Rosen grew up in West Orange, New Jersey, in a liberal, middle-class family. Coming out to her family, she says, was not difficult. "The first time I came in contact with the politics of homophobia," she says, "I was overwhelmed. I had realized at George Washington University that I was gay, but I fought it very hard. I was 22 when I finally accepted it. For a long time I felt no discrimination, but when I started lobbying in Congress I was personally affected at a level I never expected to be. Some members of Congress didn't want to talk to me, and people who assumed I was straight made snide comments about gays and lesbians in my presence. It was a turning point for me. I couldn't have lobbied with the passion I have if I hadn't decided to come out with it. It's amazing. I'd sit with a senator or a congressman who's known me for years and I'd say to him, 'I am a lesbian and the same person you've always known.' Then things seemed fine."

Despite her prominence in gay circles, in the salons and boardrooms, Rosen is more comfortable raising money and wheeling and dealing with producers to get a new anti-bigotry ad campaign on MTV than she is making speeches and headlines. "Hilary is afraid to stick her neck out," one intimate tells me. "She's afraid it will be cut off, as happens to everyone in our movement who rises up."

But Rosen claims, "I have enormous respect for the people who want to lead the parade, but I am just as happy to help them map out the route. I am not concerned about finding leaders. I am more concerned about finding foot soldiers."

On a freezing night, Patricia Ireland wraps herself up in her dark-blue trench coat and joins a couple of hundred shivering souls at a rally in Washington's Freedom Plaza to support gays and lesbians in the military. "We are going to win this fight!" she shouts into the microphone. "We've been up on the Hill...and we are going to win!" A photo would have shown her in a pose she happens to abhor, her mouth open and her fist clenched in the air. But it's a common image for the 47-year-old president of NOW, whose life is a road show of sidewalk protests and mock arrests, pitched battles with radical-right extremists, speeches in far-flung backwaters, and weekends in no-CNN motels. So to come out in the cold a couple of blocks from her 16th Street office to advance a cause she absolutely believes in is, in fact, a relief.

On the morning of our first interview, a taxi screeches to the curb in front of her office and she jumps out, her scarf slipping off and falling into the gutter. Though she is often late, she prides herself on punctuality, and she has made it here just in the nick of time. With a harried look and a battered suitcase strapped onto a flight attendant's trolley, she strides into the building.

In NOW's half-floor of offices, the phones are ringing, the staff is working at computers. She's got exactly one hour before she has to leave for a flight to Memphis. "There is an inextricable link between oppression of women and the gay-rights movement," she explains quickly, putting on her wristwatch, gold stud earrings, and Chap Stick. ''We've been talking about that since the early 70s and so it's particularly exciting to see it now beginning to click. The strategy now is to continue to reach out to other constituencies and to portray the fight as a struggle against discrimination and oppression, but of interest to a lot of people outside the movement itself. ' '

Suddenly still, her hands on her lap and her face frozen in a stiff smile, she has the look of a student at orals. She is seated in an armchair by me, not in the presidential leather swivel chair. The office looks lived in—worn industrial gray carpet, worn upholstery, banged-up cabinets—but it has large windows and a close-up view of the White House.

The National Organization for Women, the largest feminist group, with 280,000 members (twice the membership of all gay political organizations combined) and an $8.5 million annual budget, has long considered rights for gays one of its principal projects. ''NOW is an active part of the lesbian-and-gay-rights movement," she wants to make clear, not just an endorser and back-row supporter. The point is important because she has heard about the new coalition, the Campaign for Military Service, and it would trouble her if NOW, which fought the battle for years when it was not Topic A, were somehow overlooked—if NOW were assigned a secondary role. ''There is jockeying for position," she agrees. "Some of it is brutal, reflecting our society in that the guys with the money have the power. Washington is an insiders' town, and access to power is very seductive. That's happening now with the gay movement."

When her assistant comes on the intercom to tell her that the car is here to take her to the airport, she packs her files with the deliberate manner of the lawyer that she is and the cold-blooded poise of the flight attendant that she was, a veteran of unexpected bumps and sudden turbulence. Nothing seems to ruffle her. She can fix a falling hem (with the Scotch tape she carries in her bag) and disarm a hostile audience with a practiced smile and self-deprecating jokes. But she takes things to heart, and her midwestern reserve mellows as she talks about her cause and herself.

"I don't think a leader has yet emerged as a symbol and a galvanizer of the lesbian-and-gay-rights movement, and in this television age if you want a mass movement, you have to be able to reach the masses," she says. "If you are a lesbian or a gay or a bisexual and you are out there in Lafayette, Indiana, or Stillwater, Oklahoma, and somebody comes on television and says what has been in your heart, wraps words around something you can't even articulate, it makes a difference. It keeps people from feeling so isolated and alienated, like they are the only one in the world who feels that.

"Now, this fight over gays and lesbians in the military has at least a six-month shelf life," she continues, "and the civil-rights bill will spin out of that and have a shelf life of its own. I am a feminist leader and have a broader agenda that's very inclusive, but it could be," she says carefully, "that in the next six months or nine months I will be one of those people who emerge as a speaker and media person on lesbian-and-gay rights."

The truth is that for Patricia Ireland the issue is no abstraction or fad. It is hardcore and personal. Just over a year ago, as she was taking the helm of NOW, she disclosed in an interview in the gay magazine The Advocate that she has a companion in Washington. In a cover article titled "America's Most Powerful Woman Comes Out," Ireland confirmed rumors that, in addition to a husband, she had a female companion, but she refused—and refuses to this day—to label herself anything. "My aversion to labels is nevertheless tempered by the reality of the world," she tells me the next time we meet, "and the world likes labels." A year after the controversy that shook her personal and professional lives, she seems almost impervious to the criticism from all sides, including the gay community, that washed over her.

But she recalls the pain vividly, and with surprising humor. The Advocate interview was in the works for months. It is not true, she says, that the magazine threatened to out her. She had already made up her mind to talk about her personal life because she knew that as a public figure she could not keep it secret. "You know, my greatest defense mechanism is denial," she says. "So I thought about it like this: When I become president of NOW, I'll buy a new wardrobe, I'll get my hair cut, and I'll come out."

She planned to alert the NOW board and the NOW chapters beforehand to brace them for the media assault that would surely break out after the article. But The Advocate promoted the issue in advance of newsstand sales and caught Ireland off-guard. "I ended up with the feeling of personal discombobulation, but also this terrible feeling that I had blown it as far as organizational leadership. It was not fair to the activists in the field not to have known what was going on and to have been caught behind the news. For them to get a call from a reporter saying 'How do you like having a queer for a president?' was not my idea of how this media strategy would play out."

For her personally it was agony. "It was no easier than coming to terms with having had abortions. The first time I spoke out about having an abortion, it made me physically ill. It made my knees shake. It made my stomach hurt. It made my voice quiver. It made me flush. Because I am a very private person."

Ireland grew up in a quiet household in Valparaiso, Indiana, a white, middle-class Republican pocket. "You know, emotions were very low-class," she recalls bitterly. She was the younger daughter and then, suddenly, an only child when her sister died in a horseback-riding accident, a trauma Ireland rushes over except to note that it was the first time she saw her parents cry. Later, her parents adopted two younger girls. "When I look back on my childhood, I think I figured early on that the guys had a better deal. It's why I was a tomboy. It's why I always played with the guys. They had more fun. They got to wear jeans to school instead of little skirts. They could swing from the monkey bars without worrying about their panties showing."

She went to DePauw University in Greencastle, Indiana, and transferred to the University of Tennessee. She found after graduating that she was not cut out to be a teacher, one of the few professions she thought were open to women. Aimless and restless after college, she bartended and waitressed in Valparaiso until she got a job with Pan Am, back when flight attendants were called stewardesses. She got married almost immediately afterward, to a friend from college, James Humble. While her husband worked as a mason, she flew for Pan Am and attended the University of Miami School of Law.

As she climbed the ladder in a Miami law firm, she became involved in NOW and finally, in 1987, moved to Washington to join the NOW staff. For the past six years, she and Humble, who is now a businessman and artist, have lived mostly apart, he in their farmhouse south of Miami and she in Washington.

When the Advocate article came out, she found support in places where she didn't expect any—but in the people and places where she had thought she would find it, there was startling silence. "There was the perception by some people that I was somehow afraid or ashamed." In fact, many in the gay movement still resent her refusal to come entirely out by proclaiming herself a lesbian.

But she has her champions. "Patricia Ireland brought many people into the movement because of her revelations," says Robert Bray, an official of the National Gay & Lesbian Task Force. "She perfectly articulated the feminist creed that the personal is the political, and she explained it in a way that bridged the feminist and gay movements. That's what was so inspiring. She just said, 'This is what is happening in my life.' As a gay man, I thought this was amazing."

One evening in Manhattan, Patricia Ireland is the toast of a private dinner on Fifth Avenue, a high-minded affair arranged to honor her as this year's Goldberg Lecturer for a speech she will deliver after dinner at the 92nd Street Y. "Such integrity, such bearing," exults one man. "She should be mayor of New York."

As befits a V.I.P., she is booked at an Upper East Side hotel, chauffeured around town, and asked for her autograph. But she is alone backstage during the introduction, scribbling notes. Then she steps out onto the stage, exuding that self-confident corporate-lawyer air. There's not even a hint of stage fright as she plunges into her speech, which she has jotted down on a yellow legal pad. She runs through all the tested feminist issues—abortion, harassment, unequal pay, child care—then segues deftly into a plea for lesbian-and-gay rights.

In the question-and-answer session that follows, an elderly man stands up to tell her he agrees with everything she said but one thing. "Why are you promoting homosexual rights?" he shouts. She waits until he's through, her eyes steeled, her hands firmly on the lectern. But when she speaks, it is with a gentle tone that defuses the situation. "This reminds me of my father, who is now retired in Florida," she says with a fond smile. "He used to be dead set against my beliefs on gays. But the other day we were talking, and he said, 'You know, you were right.'

"I hope you," she says to her elderly critic, "will have the heart to come to believe that, too."

There are moments when David Mixner wishes it would all go away. "Fame, I know, is fleeting. And now, with all this, I feel more isolated than ever, more alone. AIDS robbed me of joy, the spirit of fun. I've lost 189 friends to AIDS and I feel a rage because it didn't have to happen."

When the phone rings in his room at the Four Seasons, he goes into belly laughs, he jiggles, he taps his foot, he sucks on Life Savers, he sips Diet Coke. "We're going to get those sons of bitches," he says, blasting away at the person on the other end of the line. "We're going to win this." In the next phone call, he's saccharin-sweet. "Honey, we get such little good news. We might as well roll in it."

By now it is past four in the afternoon. All day long Mixner has been plotting the plan of attack for the military-ban hearings and the April 25 march. One minute he's lining up telegenic witnesses: Midshipman Joseph Steffan, Lieutenant Tracy Thome of the Navy, Colonel Margarethe Cammermeyer of the National Guard—all dismissed from the armed forces despite impeccable records because they are gay. The next minute he's trying to figure out how many Porta-Johns will be needed along the march route.

He has appointments that will keep him up past midnight, and though he is getting a little cranky, he is still thinking out loud. "This is a community that has found its voice," he declares, "and we will sit down at the table of the American family at last." It's not just about politics, he stresses, but also about personal lives. "I want to fight for gays and lesbians to have love, happiness, and fun. And I don't want to deny that to myself. I am a leader but not a martyr. Five years from now, I want to still be doing this, maybe as a teacher or a writer.. .and I also want to have a lover."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now