Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCUBA LIBRE

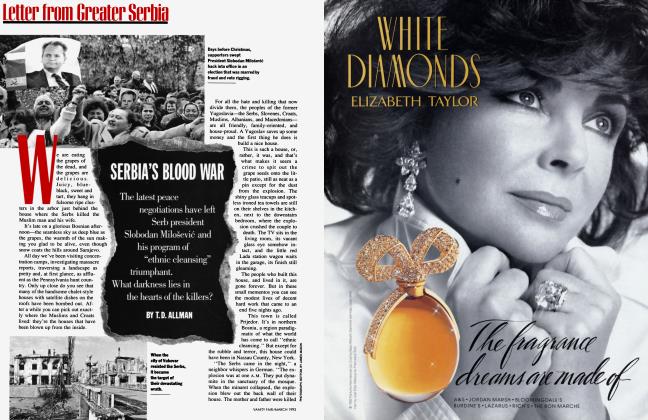

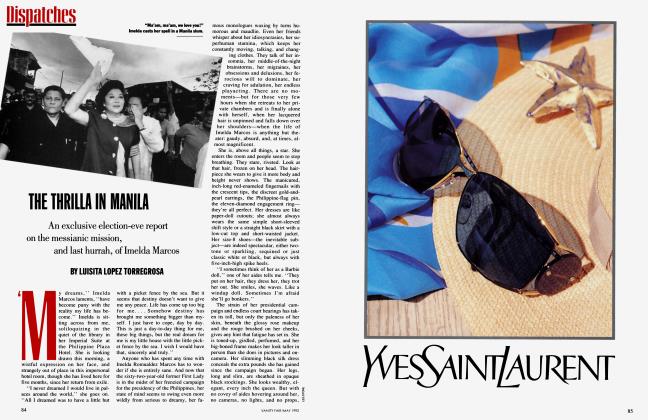

Dispatches

In 1991, Major Orestes Lorenzo Pérez defected from Cuba in a MiG-23. In December, he returned in a vintage Cessna to make a daring, white-knuckle rescue of his wife and children

LUISITA LOPEZ TORREGROSA

On the spotless red brick sidewalks that wind by the candycolored storefronts and around the gleaming blue turrets of Cinderella Castle, in a Magic Kingdom "where storybook dreams come true," the crowd of pastel-dressed tourists stands in the midafternoon heat, craning their necks for a glimpse of "ORE! ORE! ORE!" And there he is, standing and waving on Main Street, U.S.A., Major Orestes Lorenzo Perez, a strapping six-footer with a guileless smile—son of the Cuban revolution, ace fighter pilot, daredevil defector, model husband and father—and now, after his awesome life-or-death 100-minute rescue of his family in Cuba just six days before Christmas, an instant celebrity, a real-life action hero among Disney's giant cartoon characters.

Overnight, it seems, his name and face have become familiar to millions of American television viewers and millions more around the world. At a time when 2,000 Cubans a year risk their lives on leaky boats to cross the Straits of Florida and 30,000 Haitians beg for a berth in the land of the free and the home of the brave, it is the Orestes myth that has captivated the American imagination. His fans call him "James Bond Lorenzo." The president of the United States chats him up as they sit side by side in the Oval Office. Dozens of New York publishers and Hollywood producers swoop down, dangling juicy book deals and movie offers (at least 50 so far). Newspaper clippings hailing his feat already fill a two-inch-thick scrapbook, and letters pour in from ordinary folk and exiled Cubans, from powerful United States senators such as Jesse Helms of North Carolina and Larry Pressler of South Dakota. Sweeping the publicity stakes, from Larry King to Jay Leno to Good Morning America, the 36-yearold has charmed his way into American lore, mesmerizing his audiences with his tale of bravery and love.

On this New Year's Day, two weeks after completing the most celebrated solo flight since his own defection from Cuba in a Soviet-made MiG-23 two years ago, the hero stands in the center of America's favorite fantasyland and cuts an endearing if somewhat ridiculous figure: he is wearing Mickey Mouse ears. The Disney World public-relations machine has offered him and his family four all-expenses-paid days in exchange for his services. And so he is here, where the palm fronds look waxed and the bougainvillea plastic, to lead the daily parade featuring Disney perennials, 40-foot balloons of Mickey and his friends, a troupe of swishy dancers, and gawky clowns.

Orestes and his postcard-cute wife, Victoria, and their young boys, 11-yearold Reyniel and 6-year-old Alejandro, are sitting up in a fire truck, waving and smiling at the fans. Photographers and television cameras track their every move, capturing for posterity the images of the Lorenzo family in their all-American black Mickey Mouse caps, their Mickey Mouse T-shirts, their mall jeans and sparkling white athletic shoes. But, for all their smiles and hand waving, for all the happiness over their newly found American Dream, they seem dazed and frightened, clinging tightly to each other as if holding on to their lives.

"It's like being in a dream," Orestes tells me when we finally find time to sit down together, in the living room of their luxurious two-bedroom suite at the Disney Beach Club Resort, a Victorian concoction of lagoons, pools, pink marble floors, pink wallpaper, and pinkish furniture. "The hardest thing is to find our privacy again.'' His caramel-colored eyes are bloodshot from lack of sleep, anxiety, and endless public appearances. "We haven't had time to sit like this, to talk," he says, looking over at Vicky, who nods sadly. But just as he offers drinks, the phone rings. "Vicky, get the drinks," he commands in his military voice. With a strained smile, Vicky brings out glasses of beer and Diet Coke, potato chips and crackers, apologizing for the spare fare in the mini-bar.

Then, at last, she settles into an armchair beside me and curls up, running her fingers through wavy blondish hair. She seems exhausted, with deep sallow circles under her eyes, but she still looks younger than 35 in her fuchsia Mickey Mouse T-shirt and new Avia running shoes. Her face has few lines, and her dimpled smile belies the harrowing experience she's endured. She has the diffidence of a simple housewife, deferring always to her husband, when in fact she's a dentist and, by all accounts, a formidably strong woman. "I haven't had time to tell him some of the things that happened to me in Cuba," she says. "We're with people all the time. We have no time for the kids. And they are really upset about all this attention. It's been like this since we arrived in Florida on December 19. Incredible."

The saga of Orestes Lorenzo and his family culminated on that Saturday, "a magnificent day," he remembers happily, pulling up a chair to begin telling his story. He carefully recounts the tale, the microscopic details of those crucial minutes as he flew across the Straits of Florida to Cuba, a rosary and a medal of the Virgin of Charity, Cuba's patron saint, around his neck, and a map of Cuba and a Minolta Freedom AF35 camera at his side. He relives his spectacular adventure in a surprisingly even tone, without sentimentality or bravado, like a military briefing.

Late in the afternoon of Saturday, December 19, Orestes paced up and down the airstrip at Marathon Key, anxiously waiting for the exact moment he had chosen for takeoff. He checked and double-checked flight details, he prayed, he smoked, he had his picture taken standing by his plane, and he wandered around on short walks with his friends, a couple of women who had flown in to join in the vigil, Elena Diaz-Verson Amos, a wealthy Georgia widow who had bought the plane for him, and Kristina Arriaga, one of his closest friends. "I was very excited," he recalls. "I had bought two walkie-talkies, shortwave, to communicate with the tower. I gave one to Kristina. We waited for five o'clock hanging around with Elena's pilots, walking around the airport. Everyone was going crazy."

"If you haven't heard from me in one hour and 20 minutes," Orestes warned, "you can give me up for dead."

At precisely 5:05 P.M., just before climbing into the cockpit of his 1961 twin-engine Cessna 310, he gave Kristina a grim warning: "If you haven't heard from me in one hour and 20 minutes, you can give me up for dead."

He started his engines and radioed the tower. He had told the controller he was flying south, but he didn't say where he was landing—all perfectly legal. He took off and was immediately over the aqua water of the Straits of Florida. He kept his plane as low as possible, only 10 feet above the waves, to avoid being detected by Cuban radar. A decorated veteran of 40 combat flights in Angola, he was entirely focused on his mission. "I thought of nothing but flying the plane and getting there at the right time," he remembers.

Forty minutes later, on time, he was over the northwest coast of Cuba, near the popular beach resort of Varadero. He banked alongside a 400-foot-high bridge that spans the two-lane, blacktopped Matanzas-Varadero coastal highway until he saw the stretch of flat road he had pinpointed for landing. He sighted Vicky and the kids waiting by the side of the road, just as he had pre-arranged. He had only one minute to land, pick them up, and take off again. Any delay would give spotters time to alert the Cuban air force.

He had planned the landing down to the last second, but he didn't take into account the unexpected: there was a car driving beneath him, a truck and a bus coming straight toward him, a stoplight on the side of the road. He flew over the car—which swerved off the road—and was a few feet above the blacktop, ready to squeeze between the oncoming traffic and the stoplight, when he suddenly saw a small boulder in the middle of his lane.

He takes my notebook to make a sketch of the site. In childlike strokes, he draws the road, a little car, a traffic signal, the truck and the bus, the rock, and his family (three tiny dots). Speaking excitedly, he explains the landing, jabbing at the sketch with the pen. "So I lift the left wheel and tilt the plane over the rock, missing it by inches, and missing the traffic signal and the car. I drop the plane right there, slamming on the brakes. I stop only 30 feet from the truck, which had pulled over to the side of the road. I'll never forget that driver's face. He was stunned.

"My family is running toward the plane," he continues, speeding up the action. "The propellers are in front of them, so I do a U-turn to keep the propellers away from them. When they climb into the plane, I try to close the door. Once, twice. I'm desperate. I tell myself to calm down and try again. Slowly. It closes and I start the plane, but there's almost no road for the takeoff. Then the plane almost stalls, but I bank to the north and immediately gear up, flaps up."

With his two sons and Vicky in the backseat, cradling one another and crying, Orestes didn't dare look at them. Without turning, he passed back a box of chocolates to quiet his children. Keeping the plane low, he headed straight north. "It was already dark," recalls Vicky, "and Orestes was flying so low I didn't want to look down. I kept my eyes on the sky, looking for enemy planes."

When they had crossed the 24th parallel, safely out of Cuban airspace, he turned in his seat and reached out for them, and they all cried out with their fists clenched in the air, "We did it! We did it!"

"There are no words to describe that moment," Vicky tells me. "What I remember is the look in the faces of my children. My oldest child, Reyniel, was white, white, white, and shaking all over, from head to toe, holding back tears. The younger one, Alejandro, kept crying 'Papito! Papito!' After Ore had taken off and we passed the danger, he reached out for us, and I told the kids, 'Go ahead and cry,' and then we all started crying, all four of us, and we prayed that we would make it out. And that is how we were until we reached safety and we finally could breathe."

An hour and 40 minutes after his departure from Marathon Key, Orestes and his family landed at the same airstrip, to the hugs and screams of his friends Kristina Arriaga and Elena Amos. Just before touching down, Orestes had radioed Kristina the message "Bicycle one, bicycle two. I am carrying a planeload of love.

Behind the hair-raising drama and Hollywood finish of the Lorenzo family adventure lies "a long story, a long struggle around the world," confides Orestes. What happened on December 19, 1992, can only be fully understood, he tells me, by going back to his own escape from Cuba in 1991.

His defection was front-page news in America, where he was hailed, and in Cuba, where he was officially declared a traitor. U.S. intelligence saw him as a priceless commodity, a man who was carrying Castro's military secrets in his head. He was quickly granted political asylum, as are most Cuban refugees, and he underwent extensive debriefing. Little is known about these months, when he was kept in hiding by the government. He doesn't want to discuss that side of his life, and his friends backpedal in a hurry when asked about it.

With U.S. visas for his wife and children in hand, he believed that it was only a matter of time before the Cuban government would let them go. But by the end of 1991 he was in despair, and he took to the streets. "My campaign started on January 25, 1992, in New York, in the cold, at a big anti-Castro demonstration," he says, reciting a chapter of the autobiography he will soon write. "I carried a big poster of a picture of Vicky and the boys with the word HOSTAGES in big letters above it. On that day I climbed on the speakers' platform and said a few words. The people reacted very warmly."

The warmest reaction came from Elena Amos, the wealthy, 60-ish, Cuban-born widow from Columbus, Georgia, who was struck by the young crusader's ardor and love of family. She became a solicitous mother figure to the solitary Orestes, ministering to his needs and publicizing his cause. "When I was depressed, she'd call up and cheer me up," he tells me. "She is always in good humor, always upbeat. She became a widow a year ago, and it was a bad time for her. So it seems her sadness and pain and my own sadness and pain came together, and she gave me great faith."

Elena also had heartfelt political reasons for supporting Orestes. After leaving Cuba and marrying John B. Amos, an insurance magnate, she became a powerful patron of the anti-Castro crusade. For the last three years, she has been co-chairwoman of the Valladares Foundation, a fledgling human-rights organization that gets most of its money from private contributors and corporate donors such as Coca-Cola, Pepsi-Cola, and Philip Morris. The foundation was started in 1989 by an exiled Cuban writer, Armando Valladares, who spent 22 years as a political prisoner before being allowed to emigrate.

"I drop the plane right there, slamming on the brakes. I stop only 30 feet from the truck. I'll never forget that driver's face. He was stunned."

"When I met Orestes back in October 1991," says Kristina Arriaga, the 27year-old executive director of the Valladares Foundation, "he was so naive, believing in the American people to get his family out. I told him it would not happen next week. There, was shock in his face." At her urging, he left Miami's exile community, a hothouse of intrigue, and moved to the Washington suburbs near the foundation, where he could petition congressmen on Capitol Hill. With the Valladares Foundation behind him, Orestes was able to afford a Honda Accord and a modest one-bedroom apartment in Springfield, Virginia, equipped with a TV, a video camera, a word processor, and a fax machine.

He spent hours in the foundation's office, smoking and making phone calls, desperately trying to find the person who could help him. When he finally went home, he would call Kristina repeatedly, sometimes as late as four in the morning. "He was obsessed," she recalls. "Sometimes I would try to get him out for a drink or a movie and he would say no. It drove me insane.

"He said that every day without his family he died a little bit more," Kristina continues. "I could see the gradual change in him, in the look in his eyes. When I first met him he had the look of, well, it's going to be fine. But he entered that circle of Washington politics and the doors slammed in his face, and I could see the look in his eyes and I could see him wither. Sometimes he used to come and have lunch, but we weren't able to eat. He would say he had a nightmare that he was in Cuba and he could hear his children screaming for him and he couldn't find them. Armando Valladares would invite him over to his house, but Orestes wouldn't go because, he would say, 'the voices of Armando's children drown the silence of my kids.' "

Orestes' brooding weighed heavily on his friends, but it was precisely his singleminded passion that made him a perfect symbol for the Valladares Foundation. "Orestes is the only person who embodies both the young people of Cuba and American life," says Kristina. "He has credibility. He's young and was bom and grew up in the revolution. It's different for someone who grew up in it and can say, 'I want to tell you about it.' "

Soon, Orestes began taking his crusade around the globe. Last March, he spoke before the United Nations Human Rights Commission in Geneva. "I asked the world for help," he says with some anger, "for my two young boys, for my wife, an innocent woman—but nothing happened. Then, in July, during the Iberian-American conference, I went on a hunger strike in Spain, chained myself to the gates in the Parque del Retiro, a famous park in Madrid, and for seven days I ate nothing. The president of Chile said he would intercede for me with Castro. The prime minister of Spain, Felipe Gonzalez, said he would help me. Queen Sofia spoke about me with Castro. But nothing happened. In October, I met with President Bush in Miami and he spoke publicly about me, asking Castro to let my family go. In December, I met with Gorbachev in Mexico, and spent 20 minutes speaking with his wife, Raisa, and she told me I could count on their help. But by then I had decided to go on my own."

From the outset, Orestes had been moving on two fronts. At the same time he was lobbying politicians through official channels, he was earning a pilot's license so he could fly legally in the United States (an expert on Soviet-made planes, he didn't know how to fly an American-made model). And he also had bought a map of Cuba. "I know Cuba very well," he says. "I know its defense system. I know the sites of all the antiaircraft rockets and the radars. I highlighted those on the map, and then I looked for the safest places to land. Then I had to find the places where Vicky, who was iiving in Havana with her parents, could get to most easily."

His first plan was to land by helicopter in a stadium near Vicky's house. But buying a helicopter would have cost at least $100,000. Next, he thought about buying a plane and landing on the most famous boulevard in Havana, the Malecon, in the dead of night. "But it was very dangerous," he says. ''In Malecon there are too many drug dealers and too many police. So the optimum plan was the Varadero plan."

He found his dream plane, a dented, 31-year-old, six-seat Cessna 310. He loved everything about it, especially the price, $30,000. Elena Amos donated the money to the Valladares Foundation, which handed it to Orestes.

The next stage was to communicate the plan to Vicky. He composed a long note on his computer with details of his plan, instructions, secret codes, and countersignals. Using the smallest typeface, he fit everything on both sides of a small piece of paper, and to let her know it was really from him, he used his nickname for her, Cuchita. ''Besides the note, I drew a diagram of the plane. I told her to grab the kids' hands when they were running to the plane. I told her not to speak to me when they got on the plane, and not to touch me, but to sit quietly in the back. I had to concentrate 100 percent until the danger passed.

"I told her that when the time came I would call her. And I gave her these codes to follow," he continues, dragging deeply on a cigarette. ''If you can guarantee that you'll be at the right place at the right time, then you tell me this: 'Ore, your father is thinner but well.' That meant she wouldbe on that road at 5:45 P.M. My countersignal was: 'Vicky, I am going to send you some money to buy the boys a VCR and a TV.' That meant that the next day she would have to be at the designated place." He also needed to know the exact time of sunset—to have enough light for a safe landing and cover of darkness for the escape. The code he chose was his children's shoe sizes. " 'Ore, buy the boys shoes, sizes five and a half and six and a half.' That meant the sun would set between 5:30 and 6:30."

But how would he deliver the note? In early December, Orestes and Kristina went to Monterrey, Mexico, to a humanrights conference. It was there that Orestes had his talk with Raisa Gorbachev, but the real reason for the trip was to contact two Mexican human-rights activists, Virginia Gonzalez and Azul Landeros, whom he had met some six months before. Now, in December, they offered to go to Havana to deliver his note.

"In those last days I am desperate," Orestes admits. "I haven't slept for 10 days. On December 14, the Mexicans tell me they are ready to go to Havana to see Vicky. I am in Columbus, at Elena's house, getting ready to buy the plane, but I am too anxious." The Mexican women flew to Havana on December 16, and delivered the note, along with about 800 pesos for the preparations.

"It was a small piece of paper," Vicky interjects. "It explained everything I had to do. I read it and read it and memorized it. Then I burned it. The next day the Mexicans and I went to Varadero, like tourists on the beach, and we stayed there until the sun set so I could tell Ore the exact time. When we returned to Havana, we had a little party. My parents didn't know it, and the kids didn't know it, but it was a despedida, a farewell party."

The next day, the Mexican women returned to Mexico and called Orestes to tell him that everything was set. That evening, Orestes, who was still at Elena's house in Columbus, called Virginia Gonzalez in Mexico. Using one phone to speak with Orestes and another to speak with Vicky, Gonzalez passed their messages back and forth. In five tense minutes of coded conversation, the final arrangements were made.

"I hung up the phone," says Orestes, "and that night I made a video of myself explaining that I had no help from the U.S. government. Because I knew if I was captured Castro would start a campaign saying I was with the C.I.A. So I explained my whole plan in the video.

"I left Columbus at midnight and landed in Marathon Key at 3:40 in the morning," Orestes recounts with typical precision. "I went to a motel, but I couldn't sleep. I stayed up all night reviewing my plans."

In Havana, 95 miles away, Vicky couldn't sleep either. She packed up a bag with sandwiches for the boys and the fluorescent-orange T-shirts and baseball caps that Orestes had told them to wear so he could spot them in the dark. "Nobody in my family knew anything," Vicky tells me. "My parents didn't know. Ore's parents didn't know. My children didn't know. I paced up and down my room. I was nervous but not shaky. I closed the door and lay in bed, reading the Psalms. The next morning, early, I told my parents I was going to Matanzas to see Ore's brother, who was depressed. That was my excuse. Matanzas is on the way to Varadero."

She kissed her parents good-bye and left their home. She didn't cry. With the kids in hand, and looking around to make sure she was not being followed, she waited until a state car came by. (Because of the scarcity of vehicles and gasoline in Cuba, cars are obligated to give rides to travelers.) At their next stop, they switched to a private car that was doubling as a taxi. The ride cost her 300 pesos, a staggering sum in a country where the average salary is less than 200 pesos—about four dollars—a month.

From Matanzas she took a bus to the seaside resort where she and the boys would spend the afternoon waiting for Orestes. Her children were puzzled when they didn't get off the bus at their uncle's house. "Reyniel, the oldest, started asking, 'Mami, where are we going?' I told him, 'Reyniel, please, keep your voice down and just do what I say. This is a matter of life or death. ' We got to the beach at five of one in the afternoon. We had four hours ahead of us. I gave the kids some lunch and then we started walking on the rocks that line the beach there.

"Later, I saw three policemen and I got really afraid," she recalls in a voice that quivers with the memory. "I told the kids, 'Please, go swim,' hoping the policemen would think we were just tourists. I started reading the Bible and finally the policemen went away.

"At 4:30 we finished our lunch and put on the orange T-shirts and baseball caps and started walking toward the road. We walked about 25 minutes over weeds and rocks, always looking over our shoulders because I had this feeling we were being watched."

By the time they arrived at the right spot, Orestes' plane had landed, and they started running so hard that tiny Alejandro lost his shoes. "Run, run, run," Vicky kept yelling, grabbing her sons' hands in hers. "It's Papi! It's Papi!"

Within an hour, they were on American soil. After being debriefed for less than an hour by the F.B.I. and immigration officials, they flew from Marathon Key to Miami's Opa-Locka Airport in Elena's private jet; overwrought and exhausted by the ordeal, Vicky was airsick the whole way. After a quick meeting with friends and sympathizers, they were whisked away in a Lincoln Town Car to Coconut Grove's deluxe Grand Bay Hotel, where they gave their first news conference. The next day, they flew to Washington, D.C., where they began a whirlwind of public appearances that included Larry King Live, Today, Good Morning America, CBS This Morning, and The Tonight Show.

The cheers have been thunderous. Orestes' friend and political mentor, Armando Valladares, sums it up for me: "Orestes is a true hero. He has done a tremendously heroic thing. It could have been a tragedy. It's a big thing that a father risked his life and that of his wife and children to do this. It's the force of love. "

Surprisingly, the Cuban human-rights community is not unanimous in its praise. Sandra Levinson, of the Center for Cuban Studies in New York, which supports normal relations with Castro, fears that the U.S. made a mistake in supporting someone who violated Cuban airspace. "I don't think it should be held as a heroic act," she said. Mary Jane Camejo, a research assistant at Americas Watch, said she wishes Haitian refugees received the same kind of welcome.

When they had crossed the 24th parallel, they all cried out with their fists clenched in the air, "We did it! We did it!"

But theirs is a minority opinion. For Carlos A. Gonzalez, a Cuban-born marketing director for Disney World, Orestes is a huge attraction. "His presence at the Disney parade brought out hundreds of Cubans," he reports the day after the Lorenzos' appearance. "I would guess that 30 to 40 percent of the people at the parade came out for him. We sure got a lot out of him."

For most of their lives, Orestes and Victoria Lorenzo believed that the American Dream was a nightmare. "My father was a Communist," says Orestes. "From the time I was a child, I had this pounded in me. I remember being just eight years old and my father bringing me out to his friends and asking me, 'Orestes, what would you do if I defected to the United States?' I would reply just as he had taught me: 'I would rather see you dead than a traitor to the nation.' That's the kind of thing I grew up with. I didn't do anything else. I didn't have toys. I didn't play games. I didn't go to parties. I didn't dance. Everything was the Communist Party."

He was bom on July 11, 1956, the eldest of three brothers, in the last days of the Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista, when the island was the playground of American tourists and Havana was the kingdom of mambo and high rollers, prostitutes and adventurers. But his working-class parents lived in the scruffy town of Cabaiguan, a rural crossroads in the province of Las Villas. After Castro took over, the family moved to Matanzas, where Orestes' father became a low-level government functionary. At seven, Orestes was enrolled in a state-run, military-style boarding school. "I spent my childhood marching and singing hymns to the revolution and learning to hate the United States," Orestes reminisces, a strain of bitterness in his voice. "I don't ever want to have my own children grow up like that."

For one year, Orestes' family moved to Havana, and it was there, after giving a speech at a neighborhood Communist Party youth meeting, that he met 16year-old Maria Victoria Rojas. Unlike Orestes, Vicky, the daughter of a plumber, had not grown up in a Communist household. "I wasn't indoctrinated," she says, although it never occurred to her to question the party line or defy its rules.

Four months after she first spoke with Orestes, a tall, dark, and handsome 18year-old, they became sweethearts. Theirs was, by her lights, a whirlwind romance. Less than two years later, when she was a dental student and he was applying for a state scholarship to aviation school, they married.

The next year Orestes was sent to the Soviet Union for flight school. They were to live apart for the next three years. "We wrote each other every day," she remembers softly. "He called me once a month and sent me poems." Orestes recalls this time as painfully lonely.

For Vicky, their reunion in 1980 was bittersweet. They were together again, but they lived in wretched conditions at a remote air base, Santa Clara, in a barren fourth-floor walk-up. They had no furniture, no appliances—not even a refrigerator. ' 'There was nothing there, nothing, ' ' she emphasizes, "not even a grocery store. I had to walk two kilometers to buy meat and my baby's powdered milk."

Orestes was soon posted to Angola to serve with the Cuban troops propping up the Marxist regime. Vicky moved to Matanzas to live with Orestes' parents, but she was deeply unhappy. "Reyniel started having asthma attacks," she recalls. "He missed his father. He was not quite a year old, but he already knew."

After a year of successful combat missions, Orestes was reassigned to Santa Clara, where they lived in the same cramped apartment. She had just become pregnant with their second child, Alejandro, when Orestes was sent back to an officers' school in the Soviet Union. Seven months later, Vicky and the children joined him in the city of Kalinin, now Tver. They lived the next three years in a cold, alien country whose language they barely understood. "We had just one room," Vicky says, painting a grim picture. "It was our living room, our dining room, our bedroom. Our health was not too good, but we were together again and Orestes devoted himself to the children and his studies."

In the emerging era of glasnost, Orestes and Vicky slowly began to question Communism. "We were learning more and more about the United States and what was going on around the world," Vicky explains. "We realized suddenly that Cuba had no freedom of the press. We were impressed with the revolution in Romania, but in Cuba the press played down anything that cast doubt on the system. There was very little about Eastern Europe. For the first time in our lives we started talking about defecting, but we knew this would be a big blow to our families, so we decided to return to Cuba."

Back at the Santa Clara air base, Orestes was made deputy commander. It should have been a stepping-stone for an ambitious soldier, but Orestes found it hell. "I felt like a robot, taking orders," he says bitterly. "Cuba was suffocating me."

Vicky recalls watching Orestes grow more and more depressed. "Orestes was destroyed, disgusted. He knew the country was horrible, in every sense. Economics was the least of it. He was afraid the kids wouldn't have the freedom he wanted for them. We started talking about his defecting, but for me this was terrible, to be apart from him again. Those last days before he left I would look at him and cry, and he would avoid looking at the kids, knowing he would soon be gone. The night before he left I fixed him a special meal, a little despedida. The next morning, he went to the children's room to take a last look at them. They were asleep. Ore started weeping."

At high noon on March 20, 1991, Major Orestes Lorenzo climbed into a MiG23 and took off as Vicky watched him from a distance. Flying low to elude both Cuban and U.S. radar, he landed at the Boca Chica Naval Air Station, in Key West. It was his first solo flight in a MiG-23, but he did such a good job that it was only when he flew over the air base that his plane was noticed.

His sensational defection made him a hero in the United States, but in Havana, Vicky was taken in by Cuban intelligence agents for a lengthy interrogation. Orestes' father, the ardent Communist, was so distraught at Orestes' flight that he locked himself in a room for weeks. One of his brothers lost his job.

"It could have been a tragedy. It's a big thing that a father risked his life and that of his wife and children to do this. It's the force of love."

"I didn't tell the children anything," says Vicky, who moved back with them to her parents' home in Havana. "I just said their father had gone to another province to work awhile. A month later Orestes called me from the United States. 'My love, forgive me,' he said. 'I still love you. I did this for you.' And I told him, 'I'll never forget you. Not for a minute.'

"My year alone was very hard," she continues. "Not only the absence of Orestes. I would find Alejandro crying, holding his father's picture, saying he wanted his father back. He would tell me, 'My heart is breaking for my papi.' He developed a skin rash from nerves. Reyniel never cried. He would just say, 'I miss Papi.' He wanted to show me he was strong, but I knew he was suffering too. He started having his asthma attacks again, one so bad I had to rush him to the hospital. Besides all that, the government was trying to damage me."

Vicky says she was harassed, intimidated, watched. Her house was bugged, her phones were tapped, and neighbors spied on her. Interior Ministry minions posing as allies tried to entrap her by offering to help her escape by boat, yacht, or plane. A female government psychologist assigned to Vicky's case tried to weaken her faith in Orestes, whispering that he was a womanizer, or a homosexual.

It's now past nine o'clock on New Year's Day evening, and Orestes has just spent 20 minutes on the phone discussing movie deals. He's leaning back in a rattan armchair, legs crossed, cigarette in hand. His voice booms across the room. He wants Andy Garcia to play him. He wants to write his own script. He wants to play himself. He wants money. He wants control.

Once the phone call is over, he resumes the interview, but his heart has gone out of it. He's pale with weariness, his eyes drooping, his temper fraying. "Is there anything else you need?" he asks. Vicky seems distracted by thoughts of her own. She wonders out loud when the children might come back from the theme park, and if they've had their dinner.

"I don't want to think about these movie offers right now," he says, responding to a question about his future. "We have to get back to Washington, find a school for the children, find a house, maybe in Fairfax. I want to write a book. Most important, we want to start a struggle to reunify families, Cubans and non-Cubans. We've started a group called Parents for Freedom. In February we're going to Geneva to speak to the U.N. Human Rights Commission. My boys will hold a news conference. I want to ask for an audience with Hillary. She's fought for children's rights, so I think she'll be good at this."

With barely a pause, he sails on: "I am looking for a job at the same time. I am of course a pilot, but I am very interested in journalism, especially TV. I would like to return One day to Cuba and have a program to tell the real story of the country, what we lost, everything that happened. I feel it's my duty." Vicky adds that she is eager to return to Cuba after Castro falls. "A part of my heart is there."

The next day, their suite is taken over by cables, floodlights, and television cameras from Telemundo, a Miamibased Hispanic network. Though he's had only five hours of sleep, Orestes looks just-showered and springy in a white polo shirt with a Bacardi logo, but his eyes are still bloodshot and his nerves a bit raw. "I won't pose anymore," he snaps at a photographer. " I just want to be with my children," he adds, though the children are at the pool. But when it's time to set up the shot, he settles into an armchair and looks straight at the camera, his matinee-idol smile widening. Vicky joins him, glowing in fresh pink lipstick and pink fingernail polish. She smiles bravely, ready for prime time.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now