Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

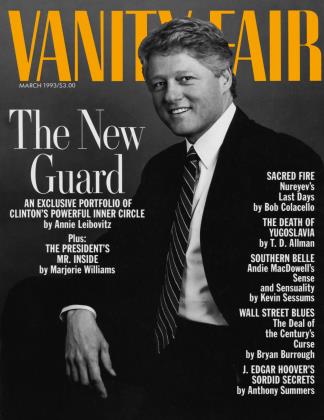

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSERBIA'S BLOOD WAR

Letter from Greater Serbia

The latest peace negotiations have left Serb president Slobodan Milošević and his program of "ethnic cleansing" triumphant. What darkness lies in the hearts of the killers?

T.D. ALLMAN

We are eating the grapes of the dead, and the grapes are delicious. Juicy, blueblack, sweet and tart, they hang in fulsome ripe clusters in the arbor just behind the house where the Serbs killed the Muslim man and his wife.

It's late on a glorious Bosnian afternoon—the seamless sky as deep blue as the grapes, the warmth of the sun making you glad to be alive, even though snow coats the hills around Sarajevo.

All day we've been visiting concentration camps, investigating massacre reports, traversing a landscape as pretty and, at first glance, as affluent as the Pennsylvania hunt country. Only up close do you see that many of the handsome chalet-style houses with satellite dishes on the roofs have been bombed out. After a while you can pick out exactly where the Muslims and Croats lived: they're the houses that have been blown up from the inside.

For all the hate and killing that now divide them, the peoples of the former Yugoslavia—the Serbs, Slovenes, Croats, Muslims, Albanians, and Macedonians— are all friendly, family-oriented, and house-proud. A Yugoslav saves up some money and the first thing he does is build a nice house.

This is such a house, or, rather, it was, and that's what makes it seem a crime to spit out the grape seeds onto the little patio, still as neat as a pin except for the dust from the explosion. The shiny glass teacups and spotless ironed tea towels are still on their shelves in the kitchen, next to the downstairs bedroom, where the explosion crushed the couple to death. The TV sits in the living room, its vacant glass eye somehow intact, and the little red Lada station wagon waits in the garage, its finish still gleaming.

The people who built this house, and lived in it, are gone forever. But in these small mementos you can see the modest lives of decent hard work that came to an end five nights ago.

This town is called Prijedor. It's in northern Bosnia, a region paradigmatic of what the world has come to call "ethnic cleansing.'' But except for the rubble and terror, this house could have been in Nassau County, New York.

"The Serbs came in the night," a neighbor whispers in German. "The explosion was at one A.M. They put dynamite in the sanctuary of the mosque. When the minaret collapsed, the explosion blew out the back wall of their house. The mother and father were killed instantly. The children were sleeping upstairs with their grandmother," he adds, ''and survived. They fled. No one knows where."

''I suppose he was a guest worker in Germany, like you," I say. ''That's how he paid for the house."

"No, he was a salesman—computers," the neighbor answers. "A young man, well educated, not mixed up in politics. Sir," he continues, "the Serbs come every night. They take two or three people. I am going to be killed soon. Is there some way you could help my children get to Stuttgart? I worked in a bakery there for eight years. My friends there could raise them."

After inspecting the debris of the mosque, we drive over to see the Roman Catholic church the Serbs blew up. This, in comparison, was a major edifice, and harder to destroy. The church is a tangle of cement and iron girders now, but the steeple stands—or rather it leans, twisted, pockmarked, scorched by the explosion.

An elderly woman, a Croat Catholic lay worker wearing a Virgin Mary medal, searches the rubble for relics. "They blew up the church five minutes after they blew up the mosque. The fire station is right over there," she says, pointing behind the church, "but the Serb firemen would not help."

Milosevic "is a master at orchestrating the killing, and giving the civilized world just enough cause to avoid military intervention."

It's getting dark now, and people scurry past us, refusing to answer questions. I knock on several doors. Finally, a Serb opens his door. Since his house faces one side of the church, windows in his house were shattered. "Blowing up the church was a bad thing to do," he says. He explains why: "Serbs live around here. Serb property was damaged. Serb people were hurt."

One Serb in his 20s is more than willing to talk. In fact, he starts screaming at me as I walk back to the church. He's wearing tight black jeans, a black Tshirt, dark-brown cowboy boots; he has a gold Orthodox cross on a gold chain around his neck, and an automatic pistol tucked in his belt.

"Get out of here!" he shouts. "You foreigners don't belong here. Prijedor belongs to the Serbs."

Until it decided to commit suicide, Yugoslavia was on its way to joining the club of affluent European nations. Yugoslavia had tourism, heavy industry; it was a food-surplus nation. The totems of an emerging consumer society were everywhere: new gas stations, motels, housing developments, discos, and sidewalk cafes in the villages. Most impressive were the large private houses covering the roadside hills. Before the killing started, practically everyone, it seems, was just finishing a new house, or had just bought a new car.

But beneath this surface modernity seethed fierce, centuries-old ethnic hatreds, which Communism had only suppressed. As the state collapsed and Slovenia, then Croatia, and finally Bosnia seceded from the Yugoslav federation, the Serbs exploded in a frenzy of killing and destruction. First they overran nearly a third of Croatia, committing atrocities unknown in Europe since World War II. Then, last spring, they overran two thirds of Bosnia.

Ever since, the world has looked on, horrified, but done nothing to stop the aggression, let alone reverse it. As I sit in my hotel room in Belgrade watching CNN, the BBC, and Sky News, peacemakers Cyrus Vance and Lord David Owen dash from Geneva to Belgrade with the latest ceasefire proposals. The faces of others I've come to interview flash on the screen: Dobrica Cosic, the novelist who is now president of what is left of Yugoslavia; Milan Panic, the American businessman from Orange County, California, who, from July to December last year, was Yugoslavia's extraordinary prime minister; and, far less frequently, Slobodan Milosevic, the president of Serbia, the man many call "Slobo-Saddam" and condemn as the mastermind of ethnic cleansing—but who, more than any other, average Serbs believe speaks for them, stands up for them, while "the world" gangs up on Serbia.

On the TV screen, all they talk about is peace. Yet afterward the pictures always switch back to Bosnia, especially to Sarajevo—the snipers, the artillery, the old people freezing to death, the children with no names because their relatives are all dead and they are too young to speak. In less than a year, Serbs have murdered more than 120,000 people in Bosnia. More than 100 formal cease-fires have been wantonly violated. According to European Community investigators, Serb soldiers in Bosnia have "systematically" raped more than 20,000 Muslim women in a premeditated campaign of sexual terror.

"Everything always goes just as Milosevic wants it," says an envoy in Belgrade. "He is a master at two things: orchestrating the killing, and giving the civilized world just enough cause to avoid military intervention to actually stop these crimes."

Repeatedly, Milosevic has strung the international community along, raising hopes for peace, dashing them, and raising them anew. Last autumn, the great expectation was that placing United Nations observers at Serb artillery positions might end the shelling of Sarajevo. After weeks of tortuous negotiations, the agreement was violated the very day it was scheduled to begin.

In December, hope took political form. After ignoring months of pleas from the outside world for democratic elections in Serbia, Milosevic finally permitted his constituents to vote for him. Not only was he re-elected, with a margin of victory that was widened by intimidation and fraud, but he also defeated and drove from office his most important rival, Prime Minister Panic.

Then, in January, hope took diplomatic form. Mediators Vance and Owen beseeched Milosevic to use his "influence" to persuade Bosnian Serbs to accept their latest peace plan—and once again Milosevic proved himself the master of events.

Within days, the previously intractable Bosnian Serbs demonstrated they had been following Milosevic's orders all along by accepting this peace plan. The "peace settlement" cost them little: like an earlier one in Croatia it confirmed both the ethnic cleansing and Serb aggression, granting Milosevic nearly everything he wanted in Bosnia. Equally significant, the threat of foreign military action was neutralized. Now, with Panic and other domestic opponents quelled in the December elections, Milosevic stood alone, more than ever the undisputed leader of "Greater Serbia."

The outside world, of course, has been too preoccupied with other matters to pay much attention to what had happened: Milosevic had triumphed; death and suffering had been visited on countless thousands of innocents with what turned out to be impunity. "On every Bosnian's tombstone," a U.N. "peacekeeper" tells me, "it should be inscribed: 'I died because Helmut Kohl and Francois Mitterrand and John Major were afraid the Maastricht Treaty wouldn't pass.' " He adds bitterly, "And on the children's graves they should write, 'It was also an election year in the United States.' "

One morning at a camp in Bosnia I notice that grown men starve differently from the way children do. We're all familiar with infantile starvation: the spindly legs, the bloated bellies, the heads too heavy for the neck to carry. But past puberty, starvation takes a different course. People come to look like sculptures. The prisoner who calls out to me, in French, "Mister, do you have a light?" looks like the effigy of a medieval martyr. You can see the skull and cheekbones—his skin is transparent. He's dying for a smoke. "It's great when you journalists visit," he says. "The Serbs let the Red Cross give us cigarettes."

As I talk to the prisoners, they whisper, mostly in German, "Tell the world. Don't let the world forget us."

Some 1,200 men are packed into this cattle shed, located on an unprotected mountainside. They are arranged in six long lines, and each man has only the space of a folded blanket where he can sit or lie down on the floor, which is not really a floor, only gravel. The gravel slopes downward, so when it rains or snows the thin blankets are soaked. There is no heat in this shed, or in any of the others in this camp, where some 5,000 people suffer in the same conditions. As I talk to the prisoners, people whisper, mostly in German, "Tell the world. Don't let the world forget us."

Red Cross workers are distributing cigarettes. But there are no matches. I give the prisoner who speaks French my lighter and ask, "Muslim or Croat?" Everyone around him laughs. "I'm Serb!" he says. "Baptized in the Orthodox Church. But the day the Serbs rounded up the Muslims in Prijedor I was taking a walk with four Muslim friends, all girls. When I explained I was a Serb, they beat me up." He's 24 and so glad to be able to light his cigarette that he grins broadly, and when he does you can see he's losing his teeth from the lack of vitamins.

Here, as in the intellectual salons of Belgrade, Serb authorities display the lack of shame or guilt that normally characterizes pathological behavior. To the contrary, the Serbs are proud of this camp. They believe it proves they are treating their "prisoners of war" decently. But aside from the fact that conditions here do not comply with the Geneva Convention, there's another noteworthy aspect to these "prisoners of war": none of them are soldiers. They are all still wearing the same light summer civilian clothing they had on when they were apprehended months ago. When I ask the Serb authorities about weapons captured from these "prisoners of war," they say there are none.

Another curiosity: there are no wounded here, or in the camp's small dispensary. They do have men who are suffering, but from diseases or malnutrition, not wounds. This raises the question of what the Serbs in Bosnia do with real P.O.W.'s. "They kill them all," an international relief official tells me.

The camp hospital is manned by imprisoned Croat and Muslim doctors. When I ask a doctor how he came to be here, he says, "I was in my surgery in Prijedor. They burst in, pointed a gun at me, and took me away. I don't know where my wife and children are."

The doctors are terrified—much more terrified than the prisoners in the shed— and later I leam why. In Bosnia it is Serb practice when they "cleanse" a town like Prijedor to terrorize average people, especially women and children, into fleeing after signing over their houses and other property. Men capable—even though not culpable—of armed resistance are imprisoned, like the prisoners in this camp. Then they kill the non-Serb elite: doctors, lawyers, engineers, businessmen, and elected officials, like the mayor of Prijedor, who, along with 48 other of the town's notables, was never seen alive again after being seized.

"Have there been atrocities? Incidences of torture?"

"Please," the doctor replies. "Do not ask such questions."

I try to compose a purely technical line of inquiry: "Given the physical circumstances of this camp—the mountain exposure, lack of shelter from the cold, and limited sanitary facilities—how many people will survive the winter?"

"Forty percent of the people here will die," the doctor says.

At Banja Luka's Bosna hotel, which looks like a Ramada Inn, I sup with the Devil, and it occurs to me that I have neglected to bring a long spoon. Actually, the police chief of Prijedor, seated on my right, is amiable, though didactic. Over cocktails he delivers a long discourse on his specialty, which he describes as "ethnic warfare." By his own account he played a major role in "cleansing" Prijedor.

As the first course arrives he opines that it's "very mean" of the media to say Serbs have committed war crimes. "You Americans do not understand ethnic warfare," he says, "because you fight only clean wars, like Kuwait and Vietnam. We do not have that luxury. We Serbs are fighting to save ourselves from genocide." He explains, almost pedantically: "In ethnic warfare the enemy doesn't wear a uniform or carry a gun. Everyone is the enemy."

Our host, the police chief of Banja Luka, sits opposite me. We are his dinner guests tonight because at 3:30 this afternoon a fellow dinner guest, Roy Gutman of New York Newsday, was arrested while he was driving along a street in Banja Luka after visiting a Muslim source. This was considered sufficient cause for him to be pulled over, manhandled, dragged into the police station, and threatened with the usual consequences. The black humor in all this was that his arrest was going to make him late for our four o'clock interview with the Banja Luka police chief.

By the time I finally found out what had happened, and reached the police station, Roy had been transformed from prisoner into honored guest. Turkish coffee was served. Would we like some slivovitz, the Yugoslav plum brandy?

The Banja Luka police chief capped our reconciliation by inviting everyone in the room to dinner, including the Prijedor police chief. Besides Roy and me, another American was present: a CroatAmerican kid from Chicago named John, who was arrested with Roy. John had come along with us from Zagreb, the capital of Croatia. But following his experience with the Serb police, he's still so scared that, even at dinner, he can't bring himself to speak.

Our host, the Banja Luka police chief, plays good cop; the Prijedor police chief is the bad cop. In an early conversational gambit, the Prijedor police chief declares that though the world is against Serbia, this won't stop the Serbs. "We will fight to the death," he vows.

There is, he explains patiently, a conspiracy against the Serbs led by the Vatican, the Muslim fundamentalists, the European Community, and the United States. Like nearly all the Serbs I meet, he believes that Serbia is a great nation, chosen to play a special role in history, and that the world is destined to pay dearly for not recognizing this fact. "We Serbs forgive, but we don't forget," he says. "We won't forget the West sided with the Muslims and Croats."

"World War I began here," a Serb official says matter-of-factly. "World War III will begin here, too."

"Yes, the world will pay a big price for opposing us," another official agrees.

"What price?" I ask.

"World War I began here," he answers matter-of-factly. "World War III will begin here, too."

This prospect seems to alarm none of our dinner companions. To the contrary, they see it as proof that they are right and "the world" is wrong. "You come from a decadent civilization," the Prijedor police chief elaborates. "You have forgotten who your real enemies are—' '

At this point the Banja Luka police chief, the good cop, breaks in. "Mr. Gutman," he says amiably, "I think you are Jewish."

"Yes," Roy answers.

"We like Jews!" he says, beaming. "Jews know how to deal with Muslims."

Roy resumes his questioning without comment. Is it true, he asks, that Serbs killed all the male children in the village of Verbanci? Can our Serb dinner companions enlighten us on the reports that 167 people were crushed to death trying to escape through an air-conditioning duct because they were suffocating in the room where they were being held? And what about the ravine story: how after a bus full of Muslims was stopped, and the passengers killed, the bodies were thrown into a ravine? There are three official responses to all such questions, punctuated by smiles and toasts to Serb-American understanding: "Muslim lies.'' "Croat lies." And: "We are investigating."

Still, even in the good cop's smile, there is puzzlement. Why should this Jew care about Muslim bodies thrown down a waterfall? Can't he understand we are all fighting the same enemy—or at least should be?

"We don't think of ourselves as Christians and Jews," I interject, attempting to lighten the conversation. "We're just a happy crew of Americans wandering around Bosnia, trying to figure out what's going on. Believe me"— my airy wave includes John, the Croat from Chicago, as well as Roy—"we spend days together in the car"—I realize I'm just getting myself in deeper and deeper—"and the subject of our different ethnicities never comes up. We just think of ourselves as fellow Americans," I conclude, grinning like an idiot because I see the Serbs think I am an idiot. To them, Roy's the Jew, who should be their natural ally in the battle to the death with Islam, but who isn't. I'm the white-bread Westerner who, however patiently they explain the obvious, Will Never Understand.

But now several of the Serbs are eyeing John. He may have been bom in Chicago, but nothing can change the fact that he is a Croat. They know exactly what would have been done to John today when he was arrested if he had not been with Roy and not had a U.S. passport. So does John.

While Roy quizzes the Banja Luka police chief, I converse with the bad cop. "That certainly was a professional job done on the mosque and church," I observe. "Who did it?"

"Not professional enough," he complains. "Vandals did it."

"That's funny," I say. "The mosque was blown up at one A.M. The church was blown up five minutes later. But there's a curfew in Prijedor. Only forces under your command are allowed out that late. And you can't just blow up buildings on the spur of the moment. It takes hours to organize such demolitions."

"We are investigating," he answers. Then he adds, "A Croat sniper was firing from the steeple of the church."

"You don't mean that night, at five past one in the morning."

"No," he says, smiling. "Before." "And the mosque? That was an enemy position too?"

"Yes, you are right. The mosque was being used by enemies of the Serbs." The police chief of Prijedor smiles. He is beginning to develop hope for me.

"And all the destroyed houses we saw?' ' "They all had bunkers."

"So the fact the Muslim houses had basements meant they had to be dynamited?"

"Yes," the police chief says. "You are beginning to understand."

After a few hours, the debris of the meal lies around us. "A number of the prisoners we saw are starving," I say.

"Because they are Muslims," the official who predicted World War III interjects. "We do everything for them, but sometimes we have only pork grease for cooking, so they refuse to eat." He adds, "They are taking food out of the mouths of Serbs."

"But Koranic dietary laws are waived in life-or-death situations. . .," I start to say, but the fatigue and the slivovitz prevent me from pursuing the point.

I begin again. "What did you do to your mayor?" I ask the police chief of Prijedor. "He was freely elected. He was your boss, wasn't he?"

"He was elected by Muslims."

"They say you killed him."

"He escaped."

"Along with the 48 other officials and civic leaders?"

"Yes. Same night. We never saw them again."

"More slivovitz!" the good cop says.

I take another sip and ask, "Do you want your children to be killers or computer salesmen?"

At this point the police chief of Prijedor stands up, looks at me, and says, "I am leaving." There's no anger or hatred in his look, only the realization he's been wasting his time. First he had to be polite to the Jew, who deserved to be arrested for consorting with the Muslim. Now he's squandered the whole dinner trying to talk sense into the American.

The Serbs believe that if you just expel or kill sufficient numbers of nonSerbs you can create a 100 percent Serb paradise. But it's as crazy to try ethnic cleansing here as it would be in Brooklyn. This is an alphabet-soup country, and this is true of everything else too. Banja Luka's electricity comes from a Muslim-held town, so this winter people in Banja Luka are dying from the cold just as they are in besieged Sarajevo. Here, as in every other place they've cleansed, the economy is dead, and even the Serbs are without hope or prospects. Though they're winning the war, the Serbs are losing the peace.

"Croat lies!" President Hadzic fires back, eyes flashing, when I ask if he will invade— perhaps igniting a civil war in Serbia.

In the Banja Luka hotel too, you can see the future written. The Serb staff— overworked and inexperienced—has no incentive to keep things up. As I leave the restaurant, I pass the kitchen. Leftover food and unwashed dishes cover the dirty stainless-steel counters. The smell follows me as I toil up the eight flights to my room in the darkness. Since there's no electricity, there's no elevator, though the hotel generator provides enough current for a dim light at the top of every other landing. Once busy with tourists and visiting businessmen, the hotel is now nearly empty, though occasionally a local couple will check in for the night.

On the fifth-floor landing I hear an extraordinary sound. It's happened to everyone: unexpectedly hearing the sound of strangers engaging in sexual intercourse on the other side of a thin wall. But never have I heard such violence associated with the act of making love. The screams of pain and rage and the violent thudding follow me up to my room, mixed with the smell of the kitchen and the sound of the automatic-rifle fire punctuating the night.

The phone in my Belgrade Hyatt Regency Hotel room rings at 6:10 P.M. "His Excellency the President will be waiting for you in the Piano Bar at the Inter-Con at 6:30," the voice says.

Altogether there are now 11 presidents and nine different currencies in the former Yugoslavia, an area only somewhat larger than Minnesota. Three hours ago, I met President Radovan Karadzic of the selfproclaimed Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, supposed chief of state of Prijedor and Banja Luka, among other territories. It was supposed to be a very important press conference. But when the Belgrade press corps assembled, it became apparent that President Karadzic had once again decided to "prove" an Islamic-fundamentalist conspiracy in Bosnia. Today, he had some "captured" Arab passports. "If this goes on," he warned in a No More Mr. Nice Guy tone, "we will accept volunteers too."

"Who would fight for you?" one flabbergasted reporter inquired.

"Romanians," the president answered, "and lots of Germans."

The listeners scratched their heads. The Romanians are Orthodox, but not Slavs. And the Germans, of course, are neither. But President Karadzic quickly drew a veil of discretion over any more explanations. "I will tell you one thing," he said. "Protestants aren't Catholics. The people in England aren't Catholics, either. People in many non-Catholic countries are beginning to understand what is at stake in the battle for Bosnia."

Following the press conference, I spoke with the president, who has been accused by the U.S. State Department, among others, of complicity in crimes against humanity and who is, by profession, a psychiatrist. It was just like the dinner in Banja Luka. President Karadzic had no sense of shame or guilt— that is, of right or wrong. "American investment will be welcome in the new Bosnia," he emphasized as we parted.

In the Piano Bar tonight, no fewer than two presidents are holding court. One is the president of Montenegro—a clean-shaven young Serb whose government, it is said, helps make ends meet by counterfeiting Marlboro cigarettes. But I'm here to meet the president with the eyes and beard of Rasputin. His name is Goran Hadzic, and he's president of the Serbian Republic of Krajina, which is the official name for the ransacked, Serb-held areas of Croatia. Waiting with the president are two thugs with shirts open to their navels so you can see their crucifixes; both have automatic pistols under their jackets. President Hadzic himself is wearing a cotton-candy-colored suit, which contrasts dramatically with his beard, eyes, and flowing hair, all of which are raven-black.

I'm meeting President Hadzic because, as usual, rumors are buzzing around Belgrade that the Serb president Slobodan Milosevic's days in power are numbered. Predictions of Milosevic's political demise have always been wrong. But what actually would happen if Milosevic were removed from power? The optimists see salvation, a way to stop the madness and the killing. But the pessimists fear Milosevic's removal could lead to a wider war, including a Serb civil war, with fighting right here in Belgrade. And it may be started by the Rasputin look-alike in front of me, who, according to numerous sources, has threatened to invade Serbia should his ally Milosevic be ousted.

"Croat lies!" he fires back, eyes flashing, when I ask if Krajina will invade should Milosevic ever be deposed. To President Hadzic's title, the introductory epithet "crazy" is usually appended. But, in this instance, he proves to have a far stronger grip on reality than most of the "experts" I've met in Belgrade. "For one thing," he points out with clairvoyant accuracy, "Milosevic will stay in power."

Then how will the war end?

As the president of Krajina surveys the future, he begins to earn back his epithet. "The war will continue another two or three years," he predicts. And then "the Russians will overthrow the traitor Boris Yeltsin and rescue us." Hadzic can just see the tanks rumbling south as Mother Russia resumes its role as leader of Slav Orthodoxy in its holy war against the Pope and Islam. "After the war is over," he adds, "we will restore the monarchy. Would you like another gin and tonic?"

Before departing, the president of Krajina kindly offers to introduce me to my third president in four hours, the president of Montenegro, who is still sitting on the other side of the Piano Bar.

In Belgrade, I have appointments with two more presidents and a prime minister: Yugoslav president Dobrica Cosic, Serb president Slobodan Milosevic, and Yugoslav prime minister Milan Panic, who was preparing to challenge Milosevic in the December election.

How did this short, wiry, 63-year-old ex-bicycle racer and California multimillionaire become the prime minister of a country that is only a half-step above Iraq on the scale of bad relations with the U.S.? "I bicycled to freedom," he explains in a typically pithy pronouncement. After defecting from Yugoslavia in 1955 during an international bicycle race, Panic arrived in the U.S. with "two suitcases and $20." He found his American dream in pharmaceuticals, and today his company is worth nearly half a billion dollars.

Because of his personal history, Panic no longer has a native tongue. He speaks English with a Serb accent and SerboCroatian with an American accent. In both languages he says out loud what others are only thinking.

"Ignorant, undemocratic, powerhungry politicians" are to blame for the war, declares Panic, referring specifically to President Milosevic, whom he once advised to go to work at Disneyland and learn from Donald Duck and Goofy. "I've told Milosevic to his face he must go," Panic says. "Several times."

Like many small men, Panic has an outsize ego. "I'm not sure how long you will last as prime minister," I tell him, "but you'd be a natural governor of California."

"Why not president?" he asks.

"That's constitutionally impossible," I point out. "You weren't bom in the U.S."

"The U.S. Constitution has been amended 27 times," he replies with a grin. "It can be amended again for me. "

I think Panic is only half joking, partly because of the faith his own life has given him that anything, even Yugoslavia, can be fixed if only talented, practical people tackle it. But his rosy optimism now confronts something terrifyingly dark and intractable: Serb chauvinism.

"They just don't get it,'' says the prime minister, launching into a more damning critique of the Serb mentality than any that have appeared in the international press. "These guys have got to understand that you just don't accomplish anything by trying to solve problems through force."

But the optimism is irrepressible, and Panic is soon talking about the limitless possibilities of the country if only it were run by live wires like him. "They can learn," he says enthusiastically, "but in order to learn you must be taught." From his press kit, he pulls out his favorite teaching aid, the "Bill of Responsibilities," published by the Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. He ticks off the obligations of responsibility until he comes to the one that resonates with what I had seen in Bosnia: "To respect the property of others, both private and public."

"But all this is meaningless to such people," I object.

"It must be made meaningful," he insists.

There is nothing hope and hard work can't achieve, according to Milan Panic, as the articles in his press kit demonstrate. THIS IS NOT A WAR OF HATE, argues one headline, NO IDEA IS WORTH KILLING FOR, proclaims another, PANIC PROMISES TO CLOSE SERBIAN CAMPS IN BOSNIA, reports a third. And then the most forthright and wishful thought, reflecting his own incredible journey: YUGOSLAVS WILL LIVE LIKE AMERICANS.

A week after meeting Panic I visit Yugoslav president Cosic, a courtly 72year-old who is Serbia's most revered living novelist. The president receives me in the same vast salon where Tito received the world's statesmen, and begins the questioning: how sweet do I like my coffee?

"Please study my books," President Cosic replies. "Mil not find one passage in which I condone ethnic cleansing."

The president makes it clear he would prefer to discuss viticulture and literature to warfare; writing novels is his vocation, cultivating grapes his avocation.

"Mr. President," I say, "people tell me your novels are a major source of this catastrophe."

"Please study my books," he replies, his eyes twinkling. "You'll not find one passage in which I condone ethnic cleansing."

Cosic has been described variously as the Solzhenitsyn or the Tolstoy of Serbia. His novels, vast romantic depictions of Mother Serbia's thousand-year struggle for freedom, are certainly not programs for the genocide of non-Serbs. "But," one person who has studied them told me, "they were decisive in creating the intellectual and emotional climate of Serb nationalism in which such outrages came to seem rational. As discontent grew with Tito and Communism, Serbs had a choice between a future on the Western European model or retreating into the mythical heroics of the past. They chose the past, in large part because of Cosic."

Like most presidents in what was Yugoslavia, Cosic is on his way somewhere, in this case Geneva, where, as always, some breakthrough to peace seems imminent. "Next time," says the president, smiling and shaking my hand, "we'll discuss books, we'll sip wine, we'll get to the bottom of things."

"The president fully understands the dimensions of the catastrophe," someone close to Cosic assures me later. "He understands how his own work has been used to justify criminal excesses of Serb nationalism. Now he is determined, if he can, to write a happy ending. Believe me, if he could remove Milosevic and stop the war, he would."

The surreal irony of the situation was that Milosevic had created the men who were trying to depose him. Nearly a year ago, when Serb atrocities first outraged the world, Milosevic decided to apply some cosmetics to the face of his regime. He arranged to have the grandfatherly Cosic made president of what remained of the Yugoslav federation. In turn Cosic, with Milosevic's approval, appointed Panid, the amiable SerbAmerican multimillionaire. But though they turned against him, Cosic and Panic have inadvertently served Milosevic's grand design very well. The Serbs have spoken with so many contradictory and confusing voices that outsiders could choose to hear whatever they wanted. "Milosevic is a genius when it comes to confusing things," a Belgrade realist pointed out. "That's why he's winning." And so, while still controlling everything, Milosevic camouflaged himself in a babble of voices.

Later, I remembered what one of Panic's American aides had told me: "I was covered in blood." When he was named prime minister, Panic flew into Sarajevo, dreaming he could make peace with such dramatic gestures. But neither his courage nor his idealism impressed the snipers. One shot hit his aide's car, and the U.S. journalist sitting next to him bled to death.

And in the end, Milan Panic would leave office as he entered it—with everything just as Slobodan Milosevic wanted it: covered in blood.

I am left with one president to go, by far the most important—Slobodan MiloSevic. On the surface Milosevic, like Serbia itself, seems modem: he speaks English and dresses like the international banker he once was, representing a Yugoslav state bank in New York. But beneath the pinstripes beat the great, dark themes of Serb nationalism: religion, ideology, bitterness, and death. His father was an Orthodox priest, his mother a devout Communist. Both committed suicide.

To explain the legacy of Serb bitterness Milosevic inherited and exploited, most Serbs go all the way back to 1389, when they lost a battle in the southern region of Kosovo to the Turks, who maintained control of the area until 1912. Most national myths are built on victories, but for half a millennium the Battle of Kosovo has been the defining moment of the Serb people, who see themselves, often with reason, as outnumbered victims of barbaric aggression, betrayed by the world.

This chronic Serb sense of aggrievement produced its most tragic result in 1914, when Gavrilo Princip—Serb nationalist terrorist and spiritual grandfather of today's Serb terrorists—assassinated Austria's Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. At the cost of millions dead in World War I, the hated Austrian and Ottoman empires were destroyed.

But, as Serbs saw it, their dream of a unified Greater Serbia had been betrayed once again. The entry of the U.S. into the fighting, followed by President Wilson's Fourteen Points, had transformed the conflict into "the war to end all wars." Wilson's solution for ending all wars was simple—and, as the future would prove, simpleminded as well. Since wars in Europe were fought over national boundaries, Wilson concluded that the way to prevent future wars was to redraw the map of Europe so that each national group would live, happy and contented, in a nice little nation-state of its own. But when it came to Serbia and its adjacent lands, the demographers threw up their hands. It was no more possible to draw neat national boundaries in the region in 1918 than it would be at the U.N. today.

So a new multinational empire was cobbled together, called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. It included territories that had previously been parts of Austria, Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, Serbia, and Montenegro, and though its peoples were mostly Slavs who largely spoke the same language, what really united them was hate.

In 1934, just 20 years after the murder of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, a Croat terrorist killed King Alexander Karageorgevic of Yugoslavia during a state visit to France. This crime was as fateful for Yugoslavia as Princip's original crime had been for the world. It destroyed at a stroke any possibility of Yugoslav cohesion in the era of Hitler and Mussolini. Five years later, when World War II began, the "Yugoslavs" turned on one another with a viciousness that mirrored the collapse of European civilization. From 1941 to 1945, 1.7 million Yugoslavs, more than 10 percent of the total population, were killed—mostly by other Yugoslavs. The worst atrocities were committed by Croat Fascists, the UstaSi, deepening the Serb sense of betrayal.

Yet after the war, these disputatious peoples, more divided than ever because of the recent atrocities, were forced to live together again, under the control of Josip Broz, the peasant son of a Croat father and Slovene mother. Like many a Balkan king, he began as a warlord and, even before assuming power, took a reign name: Tito. For 35 years the Communist dictator, who dressed like a king in a white field marshal's uniform, ruled his strange, hybrid country with an iron hand and a velvet touch. But in the vacuum left by Tito's death, in 1980, history was preparing to repeat itself.

At exactly five o'clock, I dial the six digits of Milosevic's bunker. "Yes," answers a voice.

The Croats, Slovenes, and others were tired of repression, tired of Communism—most of all tired of living under what they regarded as Serb domination. But as Serbs saw it, they were the victims. Even today Serbs constantly point out that "Josip Broz" was no Serb—only the latest in a string of foreign oppressors. And the Serb sense of bitterness and betrayal resulted in a repudiation of Tito that had a typical Balkan twist to it: many Serbs assured me Tito was not a man. "He was a woman," they still say—a castration of the dominant Yugoslav leader of the 20th century that sums up the Serbs' own sense of having been emasculated by history.

In Tito's Yugoslavia, Milosevic was a climbing apparatchik. In 1987, Serb nationalists started holding demonstrations at the hallowed Kosovo battle site, protesting the political power exercised by the region's Muslim Albanian majority. Things got out of hand when the government television channel, which Milosevic controlled, showed Albanian police beating Serb demonstrators. Instead of calming the situation, Milosevic turned the crisis into tragedy. He denounced local authorities and roused the Serbs to a fever pitch. "No one will beat you again," he vowed—a promise he betrayed soon afterward when his tanks crushed democracy demonstrators on the streets of Belgrade.

The faceless apparatchik was now a national hero. By 1989 he had imposed a police state on Serbia. As Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia broke away, Milosevic dealt with them as brutally as he had dealt with the Albanians in Kosovo. "If we must fight, then my God we will fight," he declared in a famous speech. "Because if we don't know how to work well or to do business, at least we know how to fight well."

My interview with Milosevic is set for a Tuesday, three P.M. sharp. Diplomatic and journalistic friends are amazed. "He never lets himself get caught in a situation where he can be asked questions he can't answer," one tells me. "He avoids responsibility for his actions. That's how he stays in power. I bet he's just diddling you, just like he diddles Owen and Vance, and Panic and Cosic."

'4 If Milosevic doesn ' t want to see me," I ask, "why wouldn't he just say no?"

"Milosevic is a conspirator," one diplomat tells me. "He survives by confusing people. That's how he distracts people from what he's really doing."

In the end, of course, the paranoids are right. The meeting is canceled— though I am assured it has only been postponed. This goes on for a week.

"The game is not completely played out yet," an ambassador in Belgrade tells me a couple of days later. On one of his crested paper napkins he writes down six numerals. "The number in Milosevic's bunker," he explains. When he is in Belgrade, Milosevic reputedly spends much of his time in a windowless, bombproof command center in the basement of the presidential palace. "Call around five tomorrow afternoon," advises the ambassador. "He'll be there."

The next day, at exactly five o'clock, I dial the six digits. "Yes," answers a voice.

"President Milosevic," I say quickly, "I'm calling about our appointment. The situation is so tragic. Please take this opportunity to talk to the American—"

"No!" interjects the voice, and there is a click.

I dial again. The phone rings 20, 30 times with no answer. I imagine Milosevic sitting in his underground bunker, listening to the phone ring over and over again, both the master and the prisoner of the situation he has created.

In the ensuing weeks, Milosevic diddles everybody. He promises to allow U.N. surveillance teams into Sarajevo, but the shelling of the city never stops. In the meantime, the Serbs begin another major offensive in Bosnia, moving forward, inexorably and brutally, to fulfill Milosevic's dark dream.

Vukovar is the most peaceful city in Milosevic's Greater Serbia, and since it is Sunday we visit a church. The church is also very peaceful because it is a ruin, like everything in Vukovar— not almost everything, not practically everything, everything. The Yugoslav army systematically destroyed Vukovar— street by street, house by house. The peacefulness of Vukovar is the peacefulness of total devastation, total death. Surveying the ruins, I think of Hue following the Tet offensive, or of Beirut. But they never were as dead as this. In the bright afternoon sunlight, Vukovar, demolished in the summer of 1991, is like one of those ghost cities of India, where 1,000 or 2,000 years ago a brilliant civilization flourished, then was extinguished.

Absurdly, money is scattered all over the church ruins like wastepaper, along with catechisms. No one picks up the money, just as no one prays here, because there are no people here anymore: I pick up a First Communion card with a little girl's photo on it and some old Yugoslav dinars to keep as souvenirs.

Vukovar, at least in terms of ruined buildings, is the biggest city in the Serbian Republic of Krajina, the president of which I'd met in the Piano Bar in Belgrade. Krajina consists of the parts of Croatia the Serbs grabbed last year when Croatia declared its independence. Everywhere the pattern was the same—the pattern I first observed in Prijedor. Serb terrorists overthrew the local government and killed the local notables. In terror, non-Serbs, along with a lot of Serbs, fled, and Greater Serbia gained another province.

But in Vukovar, as in Sarajevo, people resisted. So Vukovar was destroyed, the target of the same Serb wrath that has been directed at Sarajevo for so many months.

When I ask Serb friends about Vukovar, they answer as they always do: It was the Croats' fault, just as it was the Muslims' fault in Bosnia, and the Albanians' fault in Kosovo. The Croats shouldn't have resisted. Anyway, Vukovar really was a Serb city, and this also gave them the right to destroy it.

In fact, according to official statistics, 84,024 people lived in Vukovar and its environs before the killing started. Of these, 43.7 percent were Croat, 37.4 percent Serb, and 18.9 percent "other," which actually means "both"—since most of the others would have been either the children of mixed marriages or partners in them. Now not more than a few hundred people are still alive in Vukovar. "I need some footage of life among the ruins," says Tom Aspell, an NBC correspondent, so we go searching. The only signs of life are occasional clumps of men—some armed, some not—sitting out in the sunshine, in front of bombed-out buildings, drinking.

Sometimes when one of them went for water, she didn't make it back, and the others stayed in the cellar, dying of thirst.

Then we see an elderly couple working in their garden. May we visit them?

She rushes to make coffee, while he shows us the garden—tomatoes, pumpkins, plums. After serving the coffee, the old woman sits down in front of Tom's camera and is asked to describe what happened here. Immediately, she starts crying. She tells us that she and her neighbors spent nine weeks huddling in her basement without fuel, water, or sanitation. They survived on rotting potatoes. The nearest water was a hundred yards away. Sometimes, when one of them went for water, she didn't make it back, and the others stayed in the cellar, dying of thirst, too frightened to go searching for water or the body.

This couple, whose house and life were destroyed by Serb artillery, happen to be Serbs themselves. And like most Serbs the old man loves America because he believes America is the natural friend of the Serbs. "America must establish a program to reconstruct Vukovar," he tells me. His own program is quite specific: "Please have the Americans send me a boat," he says. He explains: "My boat was destroyed in the shelling. When the Americans replace my boat I can catch fish in the Danube."

"Was this an entirely Serb neighborhood?" I ask.

"No," his wife replies. "Slovenes next door. A Croat-Serb couple over there, Muslims, Hungarians, but mostly mixed marriages." She tries to remember what kind of a neighborhood it had been. "It was a Yugoslav neighborhood," she says.

"Now I need to do a stand-up, desolation as the backdrop," Tom decides. He picks a crossroads of desolation, what once was a busy intersection downtown. Nearby stands the only undamaged building in Vukovar. It's intact because it was built after the fighting stopped. It's called the Donald Duck Cafe.

The Serb driver and I go in while Tom does his stand-up. Actually, the driver isn't really a driver. He's a physicist, but, as he explains, "there's not much work for scientists in ex-Yugoslavia.

"Vukovar should not be rebuilt," the driverphysicist announces. "It should be left as it is, as a monument to human folly." Being a good Serb, he has not said "to Serb folly." He goes on to say, "I would fight and die for Serbia.

"But what Serbia?" he continues. "Not the Serbia that destroyed Vukovar." He then describes the mythical Serbia of great artists, poets, and scientists, that magnificent bulwark of civilization in the Balkans glorified in the novels of Dobrica Cosic—the hallucination of which, in fact, was the reason for the death of Vukovar and all the other deaths. Like most Serbs I meet, he just doesn't get it. In Europe at the end of the 20th century, to believe it is right to kill for any nation is not the source of the madness. It is the madness itself.

The Donald Duck Cafe is like the bar scene in Star Wars. One guy here is five-five, 350 pounds, and has six fingers on each hand. From the ruins, mutants have arisen. The Donald Duck Cafe is where they do their deals: currency, cigarettes, VCRs, guns, ammo, anything you want.

"Which is the killer?" I ask the driver-physicist.

"They're all killers," he replies, referring to our fellow patrons.

"No, I'm not talking about snipers and artillery. I mean, which one actually kills people with his own hands ?"

"That one," he says, making his choice with the slightest nod of the head. "He looks normal."

'And the colored girls go—"

"Voulez-vous coucher avec moi, ce soir—"

"Take me to the pilot, take me to the pilot of your soul—"

According to the music, we are lost between the moon and New York City. But we're actually in a disco in Pristina, capital of Kosovo—a region also known as "the tinderbox of the Balkans" and "the war waiting to happen." In this godforsaken place, halfway between Bulgaria and Albania, the 70s, it seems, never ended, at least in this disco. Everyone's wearing blue jeans, some with bell bottoms.

Pristina isn't like Vukovar. The buildings are still standing; there's been no war here yet. Nationalism has created a cleaner horror here—the Serb version of apartheid. Albanians aren't allowed in this disco, or into the modem hotel where we are staying.

Three years ago, under President Milosevic's orders, the Serbs did here what they later did in most places where they've seized power. Non-Serbs were summarily fired from their jobs, which were then given to Serbs. The Albanians' political and economic rights were extinguished. In essence this was the first of all the Milosevic-sponsored coups d'etat through which the Serbs would try to "cleanse" the parts of Croatia and Bosnia they wanted for themselves.

But how to "cleanse" an area where Serbs are outnumbered nine to one? There were simply too many non-Serbs to do what was done in Prijedor, so the Serbs opted for making life miserable for the Albanians: their jobs were taken away; classes at the university were taught in Serbo-Croatian only; the official use of the Albanian language was prohibited.

Meanwhile, in this disco, the Serbs party. And they smile at you. They are as delighted to see you as the police chief of Banja Luka was, because they believe that, once you see Kosovo, you will see things as they see them.

Various Serbs patiently explain it to me—why Albanians do not have the same rights Serbs do. I can never fully grasp the argument. But in Belgrade, Professor Mihailo Markovic, a Serb intellectual who has spent much time in the United States, comes closest.

When Yugoslavia was established following World War I, he reminds me, it was initially called the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. "They were the constituent peoples of Yugoslavia," he elaborates. "Therefore they have the right to dissolve the state and to redefine its internal boundaries," which is certainly one way of describing what happened in places like Vukovar. "However, the Albanians are not a constituent people. Hence, they possess no such right."

"But so few Serbs live in Kosovo," I reply, "and it's only been a part of Serbia since 1912. Why shouldn't the Albanians have the same—' '

Behind the professor's elegant legalisms glints the madness of history. "Kosovo is Serb," he says. "It always has been Serb. It always will be."

It's 6:30 A.M. I'm waiting outside the hotel in Pristina with two heavy suiteases. I've lugged them down the street a ways. This is because the Albanian president of Kosovo, Ibrahim Rugova, whom I interviewed yesterday, was kind enough to offer me a lift to Skopje, the capital of Macedonia—least known and happiest of Yugoslavia's breakaway republics. But Albanians, even presidents, aren't allowed inside the Pristina hotel. What happens if an Albanian does enter one of these Serb preserves? "The first time, they beat you up," one Albanian told me. "The second time, they kill you."

Behind the professor's legalisms glints the madness of history. "Kosovo is Serb. It always has been Serb. It always will be."

So I wait as inconspicuously as possible down the street from the hotel. When the Albanian car appears and slows down, I jump in.

At the border, each car stops, then is waved on. Stop, wave—except with the president's car, which gets a long stop before the wave comes.

Of course, like most of the presidents I've interviewed in Yugoslavia, he's not a real president. No one recognizes the Albanian Republic of Kosovo except Albania. But after the Serbs disenfranchised the Albanians, the Albanians went ahead and held their own election, and chose him as chief of state.

"What's your background?" I ask.

"I'm a literary theoretician," he replies in perfect French. "A Constructivist. I wrote my thesis in Paris." He adds, "I never thought I'd be a president, but after the Serbs closed down the university where I was a professor, I emerged as a kind of spokesman. One thing led to another and so here I am today. Did you visit our PEN center?"

Under President Rugova's leadership the Albanians, in contrast to the Croats and Bosnians, have opted for non-violent resistance. Besides their PEN center, they've got a branch of Amnesty International, and close ties with humanrights groups around the world.

All this has created problems for the Serbs. If the Albanians were shooting at them, that would provide a pretext for "cleansing." But the Albanians go in for international solidarity, not guerrilla warfare. Today the president is on his way to visit England, as the guest of some human-rights-concerned M.P.'s.

I'm bemused by this Frenchintellectual, chain-smoking, Islamic-secularist Albanian president. "A Constructivist president in a deconstructivist country," I remark.

"You could put it that way," he answers.

Knowing how French-educated intellectuals think, I say, "Among American writers, you prefer Hemingway to Fitzgerald, and Faulkner to Hemingway?"

"Most of all," the president answers, "I love Edgar Allan Poe."

At the Serb Ministry of Information in Belgrade they give you brown paper shopping bags, complete with the ministry logo on them. One expensively produced brochure contains page after page of old photographs of severed Serb heads. Never Again is its title, referring to Croat atrocities during World War II. But, of course, it is happening again, and one reason is that in these official documents there's the same reveling in brutalization that's followed me everywhere in the territories Serbs control.

I first noticed this in an official communique given to me in Banja Luka, entitled "Lying Violent Hands on the Serbian Woman":

Under such a hot, Balkanic sky every single demonstrative shape of life, every single demostrative shape of death have been unmeasurably bloodier, more vehement and rougher drawn than gloved Europe could ever imagine. Whatever the criterion of ferociousness is more venomous the roads of human and death are crueler, by all means. Wherever human bodies are getting buried into tombs, bottom of pit cannot be reached. Anyway, both the dagger and the pit have become here an institution of hatred.

In Belgrade too, the propaganda is the literary equivalent of Prijedor—explosions of rage, paranoia, and madness. Ostensibly these raging diatribes I carry back to my hotel in the Ministry of Information shopping bag are meant to show the world how evil all the innumerable enemies of the Serbs are. But they really illustrate how successfully the Serbs have poisoned their own minds.

The ministry also publishes a periodical, scholarly in format. It shows that self-brutalization takes an intellectual form as well. The publication is supposedly a compendium of distinguished commentary on the Yugoslav crisis. But the articles bear titles such as "The Evil Deeds of a Slav Pope," "Satanization of Serbia," and "European Hoodlum Democracy Will Not Break the Serbs."

Along with the satanization of everyone else, and the Serb bravado, there is the whining self-pity that runs through all extreme Serb nationalist discourse. "How Lies Travel Around the World," laments one article. "The Germans Do Not Want Our Mathematicians," complains another.

The ladies at the ministries of information treated me very kindly while I was in Belgrade—I say "ministries" because, just as Belgrade has two presidents, it has two ministries of information, one Serb, one federal. The ministry ladies work very hard, they dress very demurely, they are very polite, and they all seem well into middle age. The best word to describe them is "maternal." They answered faxes; they found facts and statistics. They got important interviews for me. They were as kind as they could be.

I wanted to show two of these ladies my gratitude; after some reflection I invited them to high tea at the Hyatt. There's a lovely salon at the far end of the atrium which looks as if it might be in Back Bay Boston. Exquisite pastries are displayed on an antique mahogany table. Waitresses wearing frilly white aprons pour tea from a silver service into porcelain cups.

My invitation aroused discreet excitement. Finally the great day arrived. As we ordered our tea and selected our pastries, it seemed to me these two ladies had had their hair done for the occasion.

We had an unspoken pact: we would discuss only light, happy things over tea. I diverted them for a time by discussing how difficult it was for foreigners to pronounce Serb names. "Your system of writing is too logical," I said. "It helplessly confuses people who speak languages like English, where the way words are spelled has no necessary connection with the way they are spoken. Take President Cosic," I went on. "I can only get his name right if I first remind myself it sounds something like 'sausage.' "

The two ladies tittered appreciatively at this witticism, and I continued: "And President Karadzic. I can never get that right. Karadzic? Karadzic! Karadzic," I said, trying out several pronunciations.

"Karadzic! President Karadzic!" the young man at the next table called out to us. He rose and rushed over to us. "You know President Karadzic?" he asked in Serbian, the ladies translating.

"First I tear out their fingernails," said the killer. "Then I cut off their thumbs; if that doesn't work I slit their throats."

"I have met him," I replied. "Do you know him?"

"President Karadzic is my friend," he said, beaming.

"Please sit down," I said.

"What do you do?" he asked.

"I'm a writer. What do you do?"

"I am a killer," he said.

"Oh, whom do you kill?"

"I used to kill people in Sarajevo," he answered. "Now I kill people in Belgrade."

The young man began pulling out all sorts of documents, which I handed to the ladies to translate. "I didn't just kill people in Sarajevo," he said. "Two years ago I killed many people in Krajina, children and women. Then I killed people in Vukovar. "

"But the war hadn't started two years ago in Krajina."

"We had started," he said.

"And what brings you to the Hyatt?" I asked.

"I like it here!" he said. "It's cozy. The service is good. And the ice cream! The ice cream here is wonderful."

"Yes," I said, "I understand that. But what I really meant to ask, if you will excuse me, is how can you afford to eat here? Tea and cakes here cost more than most Serbs now earn in a week."

"Oh, I have no problem with money," he answered. "I have plenty of money."

"Where do you get the money?"

"President Karadzic gives it to me."

"President Karadzic personally?"

"His people give it to me. Also General Ratko Mladic," he added, referring to the Serb officer commanding the Bosnian Serb army. "Fifty thousand deutsche marks at a time."

"Why do they give you the money?"

"I buy things for them, and then, when I have bought the things, they give me another 50,000 deutsche marks. You can buy anything on the Belgrade black market," he said with a grin, as though it were an ice-cream shop. "But sometimes you buy things and, even though you have paid for them, people don't deliver."

"What do you do then?"

"First I tear out their fingernails, then I cut off their thumbs; if that doesn't work I slit their throats. You're staying here in the Hyatt?" he concluded. "What's your room number?"

The two ladies looked at me, curious as to how I would respond.

"As a matter of fact I'm not staying at the Hyatt," I lied affably, trying to smile naturally. "I'm staying at the Moskva, downtown."

"What room number?"

"Three-oh-eight," I replied, praying there was a Room 308 at the Moskva Hotel. "As a matter of fact I have to get back, and I promised these two charming ladies a lift downtown."

"Do you have to leave so soon? I enjoy talking with you. I could buy you some ice cream," he pleaded. "Oh well, I'll look for you at the Moskva. I don't have enough friends in Belgrade."

Very slowly the three of us walked the enormous length of the Hyatt atrium, careful not to appear to be hurrying. Only when we got outside, beyond the enormous glass doors, did our three heads swivel backward involuntarily, in unison.

No, he had not followed us.

According to the documents he'd shown us, they told me, his story checked out. Buried among the papers was one advising psychiatric counseling.

"What if he finds you?" one of the ladies asked.

"How can he find me? He thinks I'm at the Moskva."

"You gave him your card." It was true. As a kind of friendship gift, he'd given me an Arkan button—Arkan being the nickname for Zeljko Raznjatovic, one of the most notorious, and most popular, terrorists in Serbia and recently elected to the Serb parliament. In return, I'd given him my card.

"But it only has my New York address on it." Yet at that moment we all felt the force of it: how the insane can make connections, discover secrets, seek you out.

"Well, in that case, I'm sure it will be all right," she said quickly, grasping my hand in thanks. "The tea was wonderful."

The other lady added, "Had I read about this in your article—and I am sure you will put it in your article—I would not have believed it, even though I know you personally. Except—

"Except," she went on, "there are boys like him all over Belgrade these days. Only the other morning, while I was waiting in line for the bus, a young man was boasting to everyone about the people he'd tortured in Bosnia.

"I don't understand," she added as we said good-bye for the last time, "what is being done to the Serbs."

After double-bolting the door of my room, I turned on the TV: Sarajevo, as usual; artillery shells falling. I realized I had no idea what artillery shells cost. Could you buy one, several, or many of them for 50,000 deutsche marks?

That night, when the knock came on the door, I didn't know what to do. Ignore it? Pretend no one was here? But the TV was on.

The knock came again, persistent. I walked to the door and, as silently as I could, moved the little metal cover out of the way so I could look through the little glass eye in the door. It was the night maid, come to turn down the bed.

That moment, walking to the door, was the only moment in Yugoslavia when I felt real terror. But even then what appalled me most wasn't the boy who had given me the Arkan button but those last words the nice lady from the ministry said to me: " what is being done to the Serbs. ' '

For as long as I can foresee, all journeys among the Serbs will begin and end as mine began and ended, in encounters with madness. The terror will always be no farther away than the smiling face at the next table—until the Serbs find some way to confront not what "the world" has done to them but what they have done to themselves.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now