Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

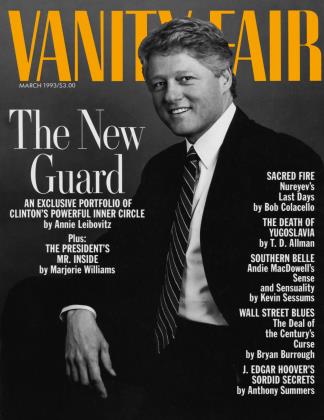

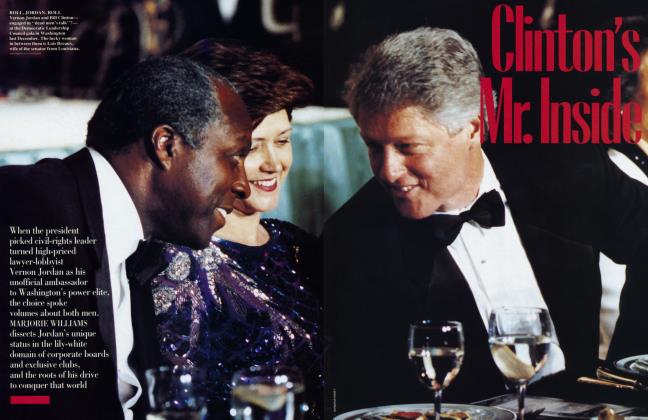

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHIDDEN HOOVER

From the 1930s through the Kennedy years, not only was J. Edgar Hoover's F.B.I. strangely reluctant to take on organized crime, the director refused to admit the Mafia's very existence. Did mobsters Frank Costello and Meyer Lansky use Hoover's secret homosexuality to blackmail the most powerful crime-fighter in the country? In this excerpt from his new book, ANTHONY SUMMERS investigates allegations of compromising photographs, Stork Club spies, and drag orgies at the Plaza hotel

J. Edgar Hoover, the potentate who was the director of the F.B.I. from 1924 until his death in 1972, had a long relationship with Mafia chieftain Frank Costello, "the Prime Minister of the Underworld." Their connection, which has never been satisfactorily explained, started with a seemingly innocuous meeting on a New York street.

Hoover recalled the occasion in a private conversation with New York Daily News journalist Norma Abrams—a confidence she kept until shortly before her death in 1989. "Hoover was an inveterate window-shopper," said Abrams. "Early one morning in the 30s, he told me, he was out walking on Fifth Avenue and somebody came up behind him and said, 'Good morning, Mr. Hoover.' It was Frank Costello. Costello said, 'I don't want to embarrass you,' and Hoover said, 'You won't embarrass me. We're not looking for you or anything.' They talked all the way to 57th Street, but God protected them, and there was no photographer around."

The contact was renewed, as Hoover explained to Eduardo Disano, a Florida restaurateur who also knew Costello. "Hoover told me he and Costello both used apartments at the Waldorf," Disano recalled. "He said Costello asked him to come up and meet in his apartment. Hoover said he told him by all means he would meet him, but not in his room, downstairs. ... I don't know what they talked about."

Costello was soon referring to Hoover as "John"—a habit he presumably picked up from the columnist Walter Winchell, a longtime friend of Hoover's, who used his table at the Stork Club almost as an office. The mobster was to recall with a chuckle the day Hoover in turn took the lead and invited him for coffee. "I got to be careful about my associates," Costello told him. ' 'They'll accuse me of consorting with questionable characters.

In 1939, when Hoover was credited with the capture of racketeer Louis "Lepke" Buchalter, it was Costello who pulled strings to make it happen. This was the time the Mob would remember as the Big Heat, when Thomas Dewey, then district attorney of New York, brought unprecedented pressure on organized crime. The heat was on, especially, for the capture of Lepke, the man known as the head of Murder, Inc.

Shortly before midnight on August 24 that year, Hoover called in newsmen to hear a sensational announcement. He, personally, had just accepted Lepke's surrender on a New York street. It was a fine tale—the director of the F.B.I., in dark glasses, waiting in a parked limousine for his encounter with one of the most dangerous criminals in America. Hoover said the F.B.I. had "managed the surrender through its own sources," and it emerged that his friend Winchell had played a role as go-between. Hoover was covered in glory, to the rage of Dewey and the New York authorities, who said he had operated behind their backs.

He had indeed, thanks to a neat piece of manipulation by the Mob. Lucky Luciano, issuing orders to Costello and his associate Meyer Lansky from prison, had decided that to relieve law-enforcement pressure on Mob operations Lepke must be made to surrender. Word went to the gangster that he would be treated leniently if he surrendered to Hoover—a false promise, as it turned out, for he was to end up in the electric chair. Costello, meanwhile, met secretly with Hoover to hammer out the arrangements.

New testimony suggests that, by the 50s, Hoover's relationship with Costello had become far more than a social contact. According to a mutual acquaintance, the New York Daily News journalist Curly Harris, Costello was by then using Hoover to get law enforcement off his back. "The doorman at Frank's apartment building," Harris remembered, "told him that there were a couple of F.B.I. guys hanging around. So Frank got hold of Hoover on the phone and told him, 'What's the idea of these fellows being there? If you want to see me, you can get to me with one phone call.' And Hoover looked into it, and he found out that the fellows weren't under any orders to do it—they'd taken it on themselves. He was very sore about it. And he had the agents transferred to Alaska or someplace the next day."

William Hundley, a Justice Department attorney, had a glimpse of the way Costello handled Hoover. It happened by chance in 1961, when Hundley was staying at the apartment of his friend—and the mobster's attorney—Edward Bennett Williams. "At eight o'clock in the morning," Hundley recalled, "there was a knock at the door. There was a guy there with a big hat on, and this really hoarse voice. It was Frank Costello, and he came in, and we sat around eating breakfast.... Somehow the subject of Hoover came up, and Hoover liking to bet on horse racing. Costello mentioned that he knew Hoover. Then he started looking very leery of going on, but Ed told him he could trust me. Costello just said, 'Hoover will never know how many races I had to fix for those lousy $10 bets.' "

In 1990, New York Mob boss Carmine Lombardozzi, aged 80, said Costello and Hoover ' 'had contact on many occasions and over a long period. Hoover was very friendly toward the families.... The families made sure he was looked after when he visited the tracks in California and on the East Coast. They had an understanding. He would lay off the families, turn a blind eye. It helped that he denied that we even existed."

To Costello and Lansky, the ability to corrupt politicians, policemen, and judges was fundamental to Mafia operations. It was Lansky's expertise in such corruption that made him the nearest there ever was to a true Godfather of organized crime. Another Mafia boss, Joseph Bonanno, articulated the principles of the game. It was a strict underworld rule, he said, never to use violent means against a law-enforcement officer. "Ways could be found,'' he said in his memoirs, "so that he would not interfere with us and we wouldn't interfere with him. '' The way the Mafia found to deal with Hoover, according to several Mob sources, involved his homosexuality.

"Hoover was wearing a black dress. Roy Cohn introduced him as 'Mary.'"

The conflicting pressures of dealing with his sexuconfusion in private while posturing as J. Edgar Hoover, masculine, all-American hero, in public would eventually drive the F.B.I. director to seek medical help. Probably in late 1946, in the wake of continuing rumors that he was a homosexual, he took his worries to a psychiatrist.

Almost all his adult life, Hoover was a patient of Clark, King and Carter, a diagnostic clinic in Washington that handled many distinguished patients. Dr. William Clark, who had founded the practice, usually looked after Hoover himself. Soon after the war, however, puzzled by a strange malaise his patient was suffering from, he referred Hoover to a colleague who specialized in psychiatry, Dr. Marshall deG. Ruffin. A product of Harvard and Cornell, Dr. Ruffin would go on to become mental-health commissioner for the Superior Court of the District of Columbia and president of the Washington Psychiatric Society. He accepted Hoover as a patient, says his widow, Monteen, because Dr. Clark "couldn't quite understand what was wrong with him.... It was the group opinion—Hoover needed to see a psychiatrist."

"Hoover was definitely troubled by homosexuality," said Mrs. Ruffin in 1990, "and my husband's notes would've proved that.... I might stir a keg of worms by making that statement, but everybody then understood he was homosexual, not just the doctors."

After a series of visits, saidMrs. Ruffin, "my understanding was that Hoover got very paranoid about anyone finding out he was a homosexual, and got scared of the psychiatry angle." Hoover ceased seeing the psychiatrist after a while, but reportedly consulted him again as late as 1971, not long before his death. Dr. Ruffin burned his case notes on Hoover, along with other patient histories, shortly before his own death in 1984.

The Mafia bosses had been well situated to find out about Hoover's compromising secret, and at a significant time and place. It was on New Year's Eve 1936, after dinner at the Stork Club, that Hoover was seen by two of Walter Winchell's guests holding hands with Clyde Tolson. Tolson, a quiet, handsome bachelor five years Hoover's junior, was from 1928 one of his closest aides and became his constant companion for the rest of his life. Today, after decades of gossip, it is clear the pair were indeed homosexual lovers.

At the Stork, where Hoover was a regular, he was immensely vulnerable to observation by mobsters. The heavyweight champion Jim Braddock, who dined with Hoover and Tolson that evening, was controlled by a Costello associate, Owney Madden. Winchell, as compulsive a gossip in private as he was in his column, constantly cultivated Costello. Sherman Billingsley, the former bootlegger who ran the Stork, reportedly installed two-way mirrors in the toilets and hidden microphones at tables used by celebrities. Billingsley was a pawn of Costello's, and Costello was said to be the club's real owner. He would have had no compunction about persecuting Hoover, and he loathed homosexuals.

Seymour Pollock, an associate of Meyer Lansky's, said in 1990 that Hoover's homosexuality was "common knowledge" and that he had seen evidence of it for himself. "I used to meet him at the racetrack every once in a while with lover-boy Clyde, in the late 40s and 50s. I was in the next box once. And when you see two guys holding hands, well, come on!... They were surreptitious, but there was no question about it."

Jimmy "the Weasel" Fratianno, the highest-ranking mobster ever to have "turned" and testified against his former associates, was at the track in 1948 when Frank Bompensiero, a notorious West Coast mafioso, taunted Hoover. "I pointed at this fella sitting in the box in front," Fratianno recalled, "and said, 'Hey, Bomp, lookit there, it's J. Edgar Hoover.' And Bomp says right out loud, so everyone can hear, 'Ah, that J. Edgar's a punk, he's a fucking degenerate queer.' "

Later, when Bompensiero ran into Hoover in the men's room, the F.B.I. director was astonishingly meek. "Frank," he told the mobster, "that's not a nice way to talk about me, especially when I have people with me." It was clear to Fratianno that Bompensiero had met Hoover before, and that he had absolutely no fear of Hoover.

Fratianno knew numerous other top mobsters, including Jack Dragna of Los Angeles and Johnny Roselli, the West Coast representative of the Chicago Mob. All spoke of "proof" that Edgar was homosexual. Roselli spoke specifically of an occasion in the late 20s when Hoover had allegedly been arrested on homosexual charges in New Orleans. Hoover could hardly have chosen a worse city in which to be compromised. New Orleans police and city officials were notoriously corrupt, puppets of an organized-crime network run by Mafia boss Carlos Marcello and heavily influenced by Meyer Lansky. If the homosexual arrest occurred, it is likely that it soon came to the notice of local mobsters.

Other information suggests Lansky obtained hard proof of Hoover's homosexuality and used it to neutralize the F.B.I. as a threat to his own operations. The first hint of this came from Irving "Ash" Resnick, the Nevada representative of the Patriarcha family from New England, and an original owner-builder of Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. In 1971, Resnick and an associate talked with the writer Pete Hamill in the Galleria bar at Caesars. They spoke of Meyer Lansky as a genius, the man who "put everything together"—and as the man who "nailed J. Edgar Hoover." "When I asked what they meant," Hamill recalled, "they told me Lansky had some pictures—pictures of Hoover in some kind of gay situation with Clyde Tolson. Lansky was the guy who controlled the pictures, and he had made his deal with Hoover—to lay off. ' '

(Continued on page 213)

(Continued from page 203)

"The homosexual thing," said Pollock, "was Hoover's Achilles' heel. Meyer found it, and it was like he pulled strings with Hoover. He never bothered any of Meyer's people. . . . Let me go way back. The time Nevada opened up, Bugsy Siegel opened the Flamingo. I understand Hoover helped get the O.K. for him to do it. Meyer Lansky was one of the partners. Hoover knew who the guys were that whacked Bugsy Siegel, but nothing was done." (Siegel was killed, reportedly on Lansky's orders, in 1947.)

There was no serious federal effort to indict Lansky until 1970, just two years before Hoover died. Then it was the I.R.S. rather than the F.B.I. that spearheaded the investigation. Even the tax-evasion charges collapsed, and Lansky lived on at liberty until his own death in 1983.

New information indicates that Lansky was not the only person in possession of compromising photographs of Hoover. John Weitz, a former officer in the Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency, recalled a curious episode at a dinner party in the 50s. "After a conversation about Hoover," he said, "our host went to another room and came back with a photograph. It was not a good picture and was clearly taken from some distance away, but it showed two men apparently engaged in homosexual activity. The host said the men were Hoover and Tolson."

Weitz would not say who his host was that evening. He implied, however, that the host also had intelligence connections. A source who has been linked to the C.I.A., electronics expert Gordon Novel, claimed he was shown similar pictures by another O.S.S. veteran, C.I.A. counterintelligence chief James Angleton.

"What I saw was a picture of him giving Clyde Tolson a blowjob," said Novel. "There was more than one shot, but the startling one was a close shot of Hoover's head. He was totally recognizable. You could not see the face of the man he was with, but Angleton said it was Tolson. I asked him if they were fakes, but he said they were real, that they'd been taken with a fish-eye lens. . . . Angleton told me the photographs had been taken around 1946, at the time they were fighting over foreign intelligence, which Hoover wanted but never got."

During his feud with O.S.S. chief William Donovan, Hoover had searched for compromising information, sexual lapses included, that could be used against his rival. His effort was in vain, but Donovan—who thought Hoover a "moralistic bastard"—reportedly retaliated in kind by ordering a secret investigation of Hoover's relationship with Tolson. The sex photograph in O.S.S. hands may have been one of the results.

There is no knowing today whether the O.S.S. obtained sex photographs of Hoover from Lansky, or vice versa, or whether the mobster obtained them on his own initiative. A scenario in which Lansky obtained pictures thanks to the O.S.S. connection would suggest an irony: that Hoover had tried and failed to find smear material on General Donovan, that Donovan in turn found smear material on him, and that the material found its way to a top mobster, to be used against Hoover for the rest of his life.

In November 1957, the zeal of a rural policeman established what competent law enforcers had long accepted, that there was indeed a Mafia, a vast national organization directed by known Godfathers of crime. On a routine inquiry about a bad check, Police Sergeant Edgar Croswell, of Apalachin, New York, stumbled onto an extraordinary gathering. Sixtythree top mobsters, from 15 states, were assembled at the palatial home of a Sicilian killer, Joe Barbara, for what could be described only as a Mafia convention.

For all of Hoover's denials that there was any such thing as a Mafia, recent events had made anyone who read the newspapers aware of its existence. Gang warfare in New York had been making headlines for months: Frank Costello shot and wounded in the lobby of his Central Park apartment building; Frank Scalise, a henchman of Albert Anastasia's, killed in the Bronx, his brother, Joseph, missing, reported shot, the body apparently dismembered and dumped; then one of the great Mafia sensations of the century—Anastasia, Costello's key protector, the man reputed to have been chief executioner for Murder, Inc., riddled with bullets in the barbershop of the Park Sheraton Hotel.

The Eisenhower government realized something had to be done. According to former attorney general William Rogers, however, Hoover had to be dragged kicking and screaming into action.

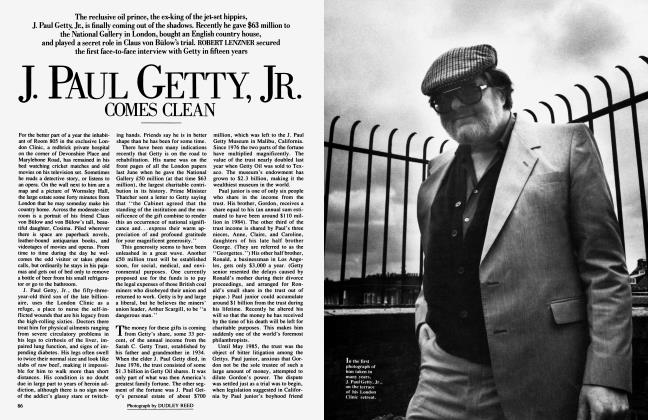

In the two years that followed, the F.B.I. gathered intelligence on organized crime as never before. Then, just as his agents were starting to make real progress, Hoover quietly let things slide. The campaign against the mobsters first slowed and then, for no apparent reason, ground to a virtual halt. A possible explanation is that Hoover had become the target of fresh blackmail—through one of Frank Costello's allies, Lewis Solon Rosenstiel.

Rosenstiel, 66 in 1957, was a hulking figure who favored amber-tinted glasses and large cigars to go with his status as one of the wealthiest men alive. As a young man, he had entered the liquor trade thanks to an uncle who owned a distillery. Then, during Prohibition, he had built up massive whiskey stocks for the day America could drink legally again. By the end of World War II his company, Schenley, had become the leading U.S. distiller, with profits of $49 million a year. By the late 50s he owned a. luxury house on East 80th Street in Manhattan, a 1,000-acre estate in Connecticut, a mansion and yacht in Florida, and a private DC-9 airplane.

The public Rosenstiel wore the mantle of business tycoon and philanthropist. Over the years he gave $100 million to Brandeis University, the University of Notre Dame, and hospitals in New York and Florida. Secretly, he was in league with the nation's top mobsters and had a corrupt relationship with Hoover. He and Hoover, moreover, reportedly took part in bizarre sex orgies.

Rosenstiel's lifelong involvement with the Mafia came to light only in 1970, when the New York State Joint Legislative Committee on Crime established that he and Mob characters had formed a consortium to smuggle liquor during Prohibition. Later, Rosenstiel had appeared at a business meeting flanked by Frank Costello. "Costello was there," a witness said, "to give them a message that Rosenstiel was one of their people. You know, if there were any problems, they would see to it."

Rosenstiel also had long-standing links to Meyer Lansky. He and Lansky "owned points together" in Mob-operated businesses, including a Las Vegas casino. During the committee's investigations, the millionaire was observed playing host to Angelo Bruno, the Philadelphia Mafia boss.

Many of the committee's leads were supplied by Rosenstiel's fourth wife, Susan. At 52, she was emerging from a decade in the divorce courts, during which Rosenstiel had spent half a million dollars attempting to concoct phony evidence. Embittered though she was, Crime Committee Chairman John Hughes had no doubts about her testimony. His chief counsel, Edward McLaughlin, now a New York judge, remembers her as an excellent witness. "I thought her absolutely truthful," he said. "The woman's power of recall was phenomenal. Everything she said was checked and double-checked, and everything that was checkable turned out to be true."

Most of Mrs. Rosenstiel's testimony to the committee was given behind closed doors, in executive session, and remains sealed. Two decades later, interviewed at her home in France, she still had the keen recall that so impressed the New York investigators. By her account, to live with Rosenstiel was to live with the command structure of organized crime.

Her first date with the millionaire, in 1955, was dinner at the Waldorf, accompanied by Lansky associate Joe Linsey. He was there again during the couple's honeymoon cruise, along with Robert Gould, a Schenley distributor who had been jailed for black-marketing in World War II. Mrs. Rosenstiel later met Sam Giancana, the Chicago Mafia boss, and Santo Trafficante Jr., the Florida crime chieftain. At Rosenstiel's birthday parties, famous hoodlums drank elbow to elbow with judges and local government officials. New York's Francis Cardinal Spellman, a friend of Hoover's, was a regular guest.

Contrary to denials by Hoover's two propaganda chiefs at the F.B.I., Lou Nichols and Cartha DeLoach, Rosenstiel was also close to Hoover.

F.B.I. files show that Hoover was aware of Rosenstiel, and extended Bureau assistance to him, as early as 1933. In 1939, Meyer Lansky used Rosenstiel as a gobetween while plotting the surrender to Hoover of Lepke. In 1946, Hoover and Tolson were guests of honor at a barbecue thrown by leading liquor companies, including Rosenstiel's. The millionaire's friendship with the director, the files indicate, began in earnest with a meeting at F.B.I. headquarters in 1956.

By the 50s, Rosenstiel was surrounded by familiar figures from Hoover's world. There was George Sokolsky, the Hearst columnist who churned out right-wing propaganda, much of it gleaned from daily calls to the F.B.I. Closest of all was Roy Cohn, the New York attorney. His services were at the disposal of Lewis Rosenstiel—not that Cohn had any genuine affection for the man. He would be disbarred, 20 years later, in part for "helping" Rosenstiel sign a document naming Cohn as his trustee and executor—when the millionaire was senile and nearly comatose.

Rosenstiel cultivated Hoover assiduously. In the 60s, he would contribute more than a million dollars to the J. Edgar Hoover Foundation, a fund established to "safeguard the heritage and freedom of the United States of America. . .to perpetuate the ideals and purposes to which the Honorable J. Edgar Hoover has dedicated his life. . . [and] to combat Communism."

There was nothing innocent about Hoover's relations with Rosenstiel. "I learned," his wife said, "how much Hoover liked the races, that he was a big gambler. And Hoover didn't have to pay off. If he won, he won. My husband would send the money through Cohn. If Hoover didn't win, he didn't pay."

Rosenstiel called in such favors, Susan said, by using Hoover to obtain the release of jailed associates, to "help with the judges" when Rosenstiel was involved in litigation—even to "put in a word" with the tax authorities.

Susan Rosenstiel met Hoover in the fall of 1957, when he came to the town house on East 80th Street. "It was supposed to be a bit cloak-and-dagger," she recalled. "Nobody was to know he was coming. He didn't come with Clyde Tolson; he came alone. I remember thinking he didn't look like the head of the F.B.I. He was rather short, and he seemed distant, arrogant. You could see he had a grand opinion of himself, and they all went along with it. Everything he said they agreed with. They talked about [Assistant Director] Lou Nichols' coming over from the F.B.I. to work for my husband. After about half an hour, I was given the wink to leave. I went upstairs to my room." (Soon, after 23 years as Hoover's closest assistant, Nichols did quit the F.B.I. to perform the same function for Lewis Rosenstiel.)

Susan Rosenstiel's most sensational revelations suggest her husband and Roy Cohn involved Hoover in sex orgies— thus laying him more open than ever to pressure from organized crime.

Susan Rosenstiel's previous marriage had collapsed because her first husband was predominantly homosexual. Now, she concluded, she had made a similar mistake. "One day," Susan recalled, "I came into my husband's bedroom and found him in bed with Roy Cohn. I was shocked, just shocked. He made some sort of joke about it being so he could be alone with his attorney. And I said, 'I've never seen Governor Dewey in bed with you,' because Dewey was one of his attorneys, too. And I walked out."

Roy Cohn flaunted his homosexuality around Susan, and seemed to take pleasure in telling her about the sexual proclivities of her husband's friends—including, especially, the homosexuality of Cardinal Spellman.

Sometime in 1958, Rosenstiel asked his wife if, while living in Paris with her previous husband, she had ever witnessed an orgy. "A few weeks later, when Cohn was there, he commented that I was a 'regular' and knew what life was, that my first husband had been gay and I must have understood, because I'd stayed with him for nine years. And they said, How would I like to go to a party at the hotel Plaza? But if it ever got out, it would be the most terrible thing in the world. I told them, 'If you want to go, I'll go.' Cohn said, 'You're in for a big surprise.' "

A few days later Rosenstiel took his wife to the Plaza. They entered through a side entrance and took an elevator to a suite on the second or third floor. "He knocked," Susan recalled, "and Roy Cohn opened the door. It was a beautiful suite, one of their biggest, all done in light blue. Hoover was there already, and I couldn't believe what I saw."

According to Mrs. Rosenstiel, Hoover was dressed up as a woman, in full drag. "He was wearing a fluffy black dress, very fluffy, with flounces, and lace stockings and high heels, and a black curly wig. He had makeup on, and false eyelashes. It was a very short skirt, and he was sitting there in the living room of the suite with his legs crossed. Roy introduced him to me as 'Mary,' and he replied, 'Good evening,' brusque, like the first time I'd met him. It was obvious he wasn't a woman; you could see where he shaved. It was Hoover. You've never seen anything like it. I couldn't believe it, that I should see the head of the F.B.I. dressed as a woman.

"There was a bar set up with drinks, and we had drinks. Not too much. I think it was about then that Roy muttered to me that Hoover didn't know that I knew who he was—that I'd think he was someone else. I certainly didn't address him the way I had at other times, as Mr. Hoover. I was afraid of my life by then.

"The next thing, a couple of boys come in, young blond boys. I'd say about 18 or 19. And then Roy makes the signal we should go into the bedroom. It was a tremendous bedroom, with a bed like in Caesar's time, with a damask spread. Hoover takes off his lace dress and pants, and under the dress he was wearing a little, short garter belt. He lies on the double bed, and the two boys work on him with their hands. One of them wore rubber gloves."

After a while, said Susan Rosenstiel, the group returned to the living room. "Cohn had brought up some food. Cold stuff, so as not to have room service.

"Then Rosenstiel got into the act with the boys. I thought, You disgusting old man.. .. Hoover and Cohn were watching, enjoying it. Then Cohn runs to get himself satisfied—full sex—with the two boys. Those poor boys. He couldn't get enough. But Hoover only had them, you know, playing with him. I didn't see him take part in any anal sex. Rosenstiel wanted me to get involved, but I wouldn't do it."

A year later, according to Susan, Rosenstiel asked her to accompany him to the Plaza again. She agreed, in return for an expensive pair of earrings from Harry Winston. Once again, Cohn ushered them into a suite to find Hoover attired in female finery. His clothing this time was even more outlandish. "He had a red dress on," Susan recalled, "and a black feather boa round his neck. He was dressed like an old flapper, like you see on old tintypes. After about half an hour some boys came, like before. This time they're dressed in leather. And Hoover had a Bible. He wanted one of the boys to read from the Bible. And he read, I forget which passage, and the other boy played with him, wearing the rubber gloves. And then Hoover grabbed the Bible, threw it down, and told the second boy to join in the sex."

When they got home that night, Rosenstiel rebuffed his wife's questions, and he never again asked her to go to the suite at the Plaza. She saw Hoover only once more, in 1961, when he and Cardinal Spellman visited the Connecticut estate.

It is not surprising that Clyde Tolson was not present at the Plaza. Thirty years had passed since the first flower of his affair with Hoover, and he was no longer the handsome young man who had attracted Hoover in 1928. He was 58, and his health was failing rapidly. Hoover and Tolson always remained intimate friends. At work, each could depend entirely on the other, and that was perhaps the real bond between them. Physical love, however, had probably run its course.

There is another account of Hoover's interest in dressing up as a woman, one that refers to an episode in Washington in 1948, 10 years before the orgies at the Plaza. It comes from two men, successful professionals in their fields, both heterosexuals, who have requested anonymity. For several months that year, they said, they frequented a Washington watering hole called the Maystat, which was noticeably, though not exclusively, patronized by homosexuals. At the Maystat they were befriended by a 50year-old army supply sergeant serving at Fort Myer. The sergeant, one of the witnesses recalled, "was decidedly gay, a bit swishy. He knew senior officers at the Pentagon, even senators and congressmen, who were also gay. It was a strange group to us, and we were fascinated."

One evening in 1948 the two young men sat in a car outside the Maystat with one of the sergeant's regular companions, a man in his mid-20s. With a conspiratorial air, he produced five or six photographs for the others to examine. "The picture he showed us first," one of the witnesses recalled, "was of a man dressed up as a woman—the whole thing, wig, evening gown, and everything. It was easily recognizable as J. Edgar Hoover. He made an ugly-looking woman. Nothing sexual was going on, at least not in the pictures we saw. No one else was in that first picture. At first we thought it might be Hoover's head stuck onto another body, a sort of trick picture, phonied up. But the other four or five photos made it clear to us they were authentic—they were taken from different angles, with other people visible, and Hoover was in all the shots. It was a party scene."

Sexual adventuring was folly for HooOver, especially in the company of a man like Rosenstiel. Meyer Lansky, who claimed that Hoover was no threat, that he had been "fixed," was Rosenstiel's close associate. Mrs. Rosenstiel quoted her husband as saying that, "because of Lansky and those people, we can always get Hoover to help us."

In July 1958, soon after the first Plaza episode—and in order to be seen to be responding to the uproar about the mobsters' conference at Apalachin—Hoover asked his Domestic Intelligence Division to produce a study on organized crime. Though the full two-volume report remains classified, an internal F.B.I. memo summarized its conclusions:

Central Research has prepared a monograph on the Mafia for the Director's approval. This monograph includes the following points on the Mafia: The Mafia does exist in the U.S. It exists as a special criminal clique or caste engaged in organized criminal activity. The Mafia is composed primarily of individuals of Sicilian-Italian origin and descent.

In 1959, Hoover himself made public speeches saying he hoped "to keep such pressure on hoodlums and racketeers that they can't light or remain anywhere." In September, in Chicago, an F.B.I. surveillance microphone hit the jackpot. Sam Giancana, the local Mafia boss, was overheard referring repeatedly to "the Commission," the cabal that ruled organized crime nationwide. He even ran through the names of its members, ticking them off one by one.

Yet, although agents regarded this as a major breakthrough, it did not move Hoover to change his stance. He would still be insisting, three years later, that "no single individual or coalition of racketeers dominates organized crime across the Nation."

Hoover's much-trumpeted onslaught on the Mob had turned out to be a phony war. It would become real enough, however, just, two years later. In Attorney General Robert Kennedy the Mob chieftains—and Hoover—would meet real opposition at last.

In September of 1955, President Eisenhower survived a near-fatal heart attack, and many, including Joseph Kennedy Sr., doubted whether he would be fit enough to run in 1956. Would the Democratic candidate be Adlai Stevenson? If so, would Kennedy's 38-year-old son be named vice president? However much Kennedy may have hoped for that, he first enthused about a very different possibility—that America might elect President J. Edgar Hoover. From Hyannis Port, he dictated this letter:

Dear Edgar,

... I think I have become too cynical in my old age but the only two men I know in public life today for whose opinion I give one continental both happen to be named Hoover—one John Edgar and one Herbert— and I am proud to think that both of them hold me in some esteem.... I listened to Walter Winchell mention your name as a candidate for President. If that should come to pass, it would be the most wonderful thing for the United States, and whether you were on a Republican or Democratic ticket,

I would guarantee you the largest contribution that you would ever get from anybody and the hardest work by either a Democrat or Republican. I think the United States deserves you. I only hope it gets you.

My best to you always.

Sincerely,

Joe

Hoover had once yearned to be president, but by 1955 he had long since given up hope of achieving that ambition. Even so, he framed Joe Kennedy's letter and kept it on his office wall for the rest of his life. It was part of a vast correspondence of mutual admiration.

The F.B.I. file on the elder Kennedy suggests a man taking out political insurance. At 67, he was a figure of immense power but dubious history. Biographers agree that, like Lewis Rosenstiel's fortune, a great part of the Kennedy fortune derived from Prohibition bootlegging in league with organized crime. Frank Costello liked to say that he had "helped Joe Kennedy get rich," that they had been partners. Harry Truman judged the elder Kennedy to be "as big a crook as we've got anywhere in this country."

J. Edgar Hoover, however, had an enduring relationship with Kennedy. They had met, some say, as long ago as the 20s, when Kennedy was financing movies in Hollywood. He introduced Hoover to a clutch of female stars who looked good at his side and belied the rumors about his homosexuality. A quarter of a century later, Hoover and Clyde Tolson became occasional guests at the Kennedy winter retreat in Florida. When there were first discussions about setting up a J. Edgar Hoover Foundation, Kennedy promised a large contribution. He once offered Hoover a princely salary to join the Kennedy organization as "security chief."

"When John Kennedy was making a strong challenge for the presidency," recalled former F.B.I. assistant director Cartha DeLoach, "Mr. Hoover asked Clyde Tolson, and Tolson told me, to make a thorough review of the files. They knew all about Kennedy's desires for sex, and the fact that he would sleep with almost anything that wore a skirt. 'Joe Kennedy told me,' Mr. Hoover said, 'that he should have gelded Jack when he was a small boy.' "

The F.B.I. file on John Kennedy had been opened at the start of World War II, based on British M.I.5 reports on his social life while visiting his father, then ambassador to Britain. In 1941, when Kennedy was a young officer in naval intelligence, Hoover began receiving reports about his relationship with a 28year-old beauty named Inga Arvad, a journalist living in Washington who was suspected of having Nazi loyalties. To separate the lovers, the navy transferred Kennedy out of Washington, a move that only increased their ardor. The romance lasted a matter of months, but during most of that time Hoover's agents listened to hidden microphones as the couple made love. The F.B.I.'s surveillance was a legitimate way of handling a potential security risk. It was also the start of lasting bitterness between Kennedy and Hoover.

"When Jack came down to Congress," recalled his friend Langdon Marvin, "one of the things on his mind was the IngaBinga tape in F.B.I. files—the tape he was on. He wanted to get the tape from the F.B.I. I told him not to ask for it.

... Ten years later, after he beat Henry Cabot Lodge in the Massachusetts senatorial race, Jack became alarmed. 'That bastard. I'm going to force Hoover to give me those files,' he said to me. I said, 'Jack, you're not going to do a thing. You can be sure there'll be a dozen copies made before he returns them to you, so you will not have gained a yard. And if he knows you're desperate for them, he'll realize he has you in a stranglehold.' "

Perhaps Kennedy did betray his fear. Just after his election to the Senate, the record shows, he asked for "the opportunity of shaking hands" with Hoover. From then until 1960, Kennedy went out of his way to flatter the man he privately called "bastard."

Hoover, while being outwardly polite to Kennedy, continued to collect smear material. In 1959, he learned that a couple named Leonard and Florence Kater had discovered that their 21-year-old lodger, Pamela Tumure, a secretary in Kennedy's Senate office, had a regular nocturnal visitor—her boss. The Katers, strict Catholics, rigged up a tape recorder to document the sounds of the couple's lovemaking and once snapped a picture of a man they said was Kennedy sneaking out in the middle of the night. They spied on him for months on end, and in the spring of 1959, with the election campaign approaching, they mailed details of the "adulterer's" conduct to the newspapers. The press shied away, but one company—Steam Publications—sent the Katers' letter on to Hoover. Soon, according to one source, he quietly obtained a copy of the compromising sex tapes and offered them to Lyndon Johnson as campaign ammunition.

"Then Hoover threw down the Bible and told the second boy to join in the sex."

"Hoover and Johnson both had something the other wanted," said Robert Baker, the Texan's longtime confidant. "Johnson needed to know Hoover was not after his ass. And Hoover certainly wanted Lyndon Johnson to be president rather than Jack Kennedy. Hoover was a leaker, and he was always telling Johnson about Kennedy's sexual proclivities."

Meanwhile, John Kennedy, like his father before him, had apparently slipped into his own shabby relationship with organized crime. He was compromised by it, and not only because of sex—caught, even before his presidency began, in the tangle of intrigue that may eventually have led to his assassination. Hoover, long since neutralized by the Mob himself because of his homosexuality, would gradually discover the extent of the younger man's folly.

The Kennedy connection with the Mafia had not ended with Prohibition. John Kennedy followed the same perilous road as his father. According to Meyer Lansky's widow, Kennedy met the mobster when he visited Cuba in 1957—even took his advice on where to find women. Not long afterward, in Arizona, he went to Mass with "Smiling Gus" Battaglia, a close friend of Mafia chieftain Joe Bonanno's. Later, he met Bonanno himself.

In 1960, when the Kennedy s were pursuing the presidency, Joe Kennedy had meetings in California with numerous gangsters. He mended fences with Teamsters leader Jimmy Hoffa, whom his son Robert—in sharp contrast to the father and the elder brother—had long been pursuing.

Thanks to a variety of sources, including F.B.I. wiretaps and Mob associates, it is now clear the Kennedys used the Mob connection as a stepping-stone to power. They reportedly asked Carlos Marcello to use his influence to win Louisiana's support for Kennedy at the 1960 Democratic convention. He refused—he was already committed to Lyndon Johnson—but Chicago boss Giancana proved helpful.

Giancana and Roselli would later be overheard on an F.B.I. wiretap discussing the "donations" they had made during the vital primary campaign in West Virginia. According to Judith Exner, who became the candidate's lover in the spring of 1960, when she was still Judith Campbell, John Kennedy himself took outrageous risks to enlist Giancana's help. He met secretly with the Mafia boss at least twice and even sent Exner to him as a courier, carrying vast sums of money in cash.

Hoover knew something of all this almost from the start. As early as March 1960—the very month Kennedy began discussing Giancana with Exner—word reached F.B.I. headquarters from "members of the underworld element" that Joe Fischetti, a Giancana associate, "and other unidentified hoodlums are financially supporting and actively endeavoring to secure the nomination for the presidency as Democratic candidate, Senator John F. Kennedy. .. whereby Fischetti and other hoodlums will have an entre [s/c] to Senator Kennedy."

In July, on the eve of the convention in Los Angeles, Robert Kennedy was told that Hoover's agents had been trying to dig up information about the conduct of the West Virginia primary. A long F.B.I. report containing "an extensive amount of derogatory information" on his brother was supposedly on its way to the Justice Department.

If John Kennedy was worried by such reports, he did not show it. His antics with women during the convention caused near panic among Democratic officials. We now know he was juggling Judith Exner, Marilyn Monroe, whom he had known off and on for years, and sundry call girls. Moreover, Los Angeles law enforcement noted his use of whores from a Mob-controlled vice ring. This, too, would eventually be reported to Hoover.

Kennedy often shrugged off warnings that his womanizing might one day ruin him. "They can't touch me while I'm alive," he said to one intimate, "and after I'm dead, who cares?" Reckless womanizing was a flaw in Kennedy's character that imperiled everything he strove for, and Hoover was one of the first to spot his weakness.

Hoover soon had an opportunity to test his power. The day after the convention, a press report forecast that—if elected—Kennedy would fire Hoover.

"Clyde Tolson called me," recalled Cartha DeLoach, "and said, 'We ought to have some feeling as to his intentions regarding the director. Why don't you get one of your friends in the press to plant a question at a press conference?' I called a vice president at U.P.I., a good friend, and asked him to ask Kennedy whether he would keep Hoover on. He did ask that question, and John Kennedy's response was immediately, without hesitation, 'That will be one of the first appointments I will make.' " Indeed, less than three weeks after his nomination, Kennedy had committed himself to reappointing Hoover.

As president, Kennedy would make light of the Hoover problem. He dismissed Hoover as a "master of public relations." "The three most overrated things in the world," he liked to say, "are the state of Texas, the F.B.I.," and whatever was currently irking him. In private, he fumed.

Kennedy told the columnist Igor Cassini, a family friend who wrote under the name of Cholly Knickerbocker, that he "knew" Hoover was a homosexual. "I talked to the president about it," said the novelist Gore Vidal, "and he gave me one of those looks. He loathed Hoover. I didn't know then that Hoover was blackmailing him. Nor did I realize how helpless the Kennedys were to do anything about him."

The bottom line was fear. "All the Kennedys were afraid of Hoover," said Ben Bradlee, former editor of The Washington Post. "John F. Kennedy was afraid not to reappoint him," said the columnist Jack Anderson. " I know that, because I talked to the president about it. He admitted that he'd appointed Hoover because it would've been politically destructive not to."

On the day Kennedy was elected, Hoover wrote him an unctuous letter. "My dear Senator: Permit me to join the countless well-wishers who are congratulating you on being elected President of the United States.. . . America is most fortunate to have a man of your caliber at its helm in these perilous days. ... You know, of course, that this Bureau stands ready to be of all possible assistance to you."

Robert Kennedy, the president's brother, who burst into the Justice Department determined to effect change, offended Hoover from the start. Everything about him was guaranteed to irritate the F.B.I. director. When Kennedy wore a tie, it often hung cheerfully askew, and the attorney general's legs spent half the day on the vast desk, not under it. An attorney general in shirtsleeves, Hoover told a colleague, looked "ridiculous." On a visit to Kennedy's office, he and Tolson looked on in confusion as the younger man sat throwing darts at a target on the wall.

Kennedy insisted on instant communication with Hoover and began by ordering the installation of a buzzer with which to summon the director at will. Hoover had it removed, only to be confronted by telephone engineers putting in a hot line. The first time Kennedy used it, recalled former assistant director Mark Felt, Hoover's secretary answered. "When I pick up this phone," Kennedy snapped impatiently, "there's only one man I want to talk to. Get this phone on the director's desk immediately."

In a stroke, Robert Kennedy had broken the mold that Hoover had fashioned over decades. He was asserting the authority of the attorney general, which Hoover had eroded, and he was severing Hoover's most treasured link of all, his oneon-one contact with the president himself. John Kennedy's secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, cannot recall a single phone call between the president and Hoover during the entire administration.

Kennedy's people, meanwhile, found Hoover very strange indeed. Joe Dolan, a slim young lawyer, found himself lectured about weight problems for 45 minutes. John Seigenthaler, Kennedy's administrative assistant, was harangued first about the way a leading newspaper was supposedly infiltrated by Communists, then about Adlai Stevenson's alleged homosexuality. Hoover subjected first Robert, then the president, to a long briefing on the alleged homosexuality of Joseph Alsop, the distinguished journalist.

It was all bizarre to the Kennedys. For the first time, perhaps, men in power dared voice the notion that Hoover was not entirely sane. "He was out of it today, wasn't he?" Robert murmured to Seigenthaler when he emerged from Hoover's lecture about Communists and pederasts. Kennedy staffers began to talk about Hoover's "good" and "bad" days.

"He acts in such a strange, peculiar way," Robert Kennedy was to say in 1964, on an embargoed basis, in an interview intended for use by future historians. "He's rather a psycho. I think it's a very dangerous organization... and I think he's. . .become senile and rather. . .frightening."

On February 4, 1961, not two weeks into the new presidency, Drew Pearson used his regular radio broadcast to report the first major battle in the younger Kennedy's war with Hoover. "The new attorney general," Pearson said, "wants to go all out against the underworld. To do so, Bobby Kennedy proposes a crack squad of racket busters, but J. Edgar Hoover objects. Hoover claims that a special crime bureau reflects on the F.B.I., and he is opposing his new boss."

Joseph Kennedy, with his long-standing ties to the Mafia, thoroughly disapproved of Robert's campaign against top criminals. Robert, however, was beyond persuasion. As attorney general, he was determined to bring real power to bear against the Mob for the first time. Yet Hoover greeted him, even before he had formally taken office, only with an exhortation to fight Communism. "The Communist Party U.S.A.," said his memorandum, "presents a greater menace to the internal security of our Nation today than it ever has." Kennedy disagreed. "It is such nonsense," he said that year, "to have to waste time prosecuting the Communist Party. It couldn't be more feeble and less of a threat, and besides its membership consists largely of F.B.I. agents. "

A collision was inevitable. Luther Huston, an aide to the outgoing attorney general, went to see Hoover a few days after the inauguration. "I had to wait," he recalled, "because the new attorney general was there. He hadn't called or made an appointment. He had just barged in. You don't do that with Mr. Hoover. Then my turn came and I'll tell you the maddest man I ever talked to was J. Edgar Hoover. He was steaming. If I could have printed what he said, I'd have had a scoop. Apparently Kennedy wanted to set up some kind of supplementary or overlapping group to take over some of the investigative work the F.B.I. had been doing. My surmise is that Mr. Hoover told Bobby, 'If you're going to do that, I can retire tomorrow. My pension is waiting.' "

News of the rift quickly leaked to the press. In Florida, after a round of golf with Tony Curtis, Joseph Kennedy tried to cover up. "I don't know where those ridiculous rumors start," he told a reporter. "Nothing could be further from the truth. Both Jack and Bob admire Hoover. They feel they're lucky to have him as head of the F.B.I."

Behind the scenes, the father begged his sons to humor Hoover. A meeting at the White House in February 1961, one of only six occasions on which John Kennedy agreed to see Hoover during the presidency, was probably set up to arrange a truce.

There was no stopping Robert, however, on organized crime. He got around Hoover's rejection of a crime commission by quadrupling the staff and budget of Justice's Organized Crime Section, and rammed expansion through whether Hoover liked it or not.

In spite of Hoover's obstruction, Robert's criminal targets were rapidly becoming enraged. Carlos Marcello and Sam Giancana became prime F.B.I. targets, mercilessly harassed by the agency that had left them at peace for so long.

The Kennedy family's differing attitudes toward organized crime were at their most extreme, and most potentially dangerous, when it came to Giancana. As the man who had reportedly helped John win the election with illegal vote buying, Giancana had hoped for an easy ride from the Kennedy Justice Department. What he got instead was a tough, ceaseless onslaught, and he felt double-crossed.

On the evening of July 12, 1961, Giancana, accompanied by his mistress Phyllis McGuire, walked into a waiting room at Chicago's O'Hare Airport during a routine stopover on their way to New York. Waiting for him were a phalanx of F.B.I. agents, including Bill Roemer, one of the mobster's most dogged pursuers. Giancana lost his temper. He knew, he told the agents, that everything he said would get back to J. Edgar Hoover. Then he burst out, "Fuck J. Edgar Hoover! Fuck your superboss, and your super-superboss! You know who I mean: I mean the Kennedys!" Giancana piled abuse on both brothers, then snarled, "Listen, Roemer, I know all about the Kennedys, and Phyllis knows more about the Kennedys, and one of these days we're going to tell all. Fuck you! One of these days it'll come out."

On January 6, 1962, Drew Pearson made a daring prediction: "J. Edgar Hoover doesn't like taking a backseat, as he calls it, to a young kid like Bobby.. .and he'll be eased out if there is not too much of a furor."

It was only a brief comment in a radio broadcast, but what Pearson said made ripples in Washington. Three days later, in a note to his brother, Robert Kennedy begged the president to keep a favorable reference to the F.B.I. in his State of the Union address. "It is only one sentence," he wrote, "and it would make a big difference for us. I hope you will leave it as it is. "

A month earlier, Hoover's spies had warned him not only that the Kennedys were planning to fire him but also that a specific candidate, State Department Security Director William Boswell, was in line for his job. And soon, having not deigned to see Hoover for the past year, Kennedy sent word that he "desired to speak with Mr. Hoover."

Hoover stepped out of his limousine at the northwest gate of the White House at one o'clock on March 22. He was ushered into the Oval Office, and then into an elevator to the dining room in the Executive Mansion. The only other person present was senior Kennedy aide Kenneth O'Donnell.

The meeting was a long one—four hours. It may never be known whether or not Kennedy tried to fire Hoover that day. The Kennedy Library says it has no record of what was said at the lunch. Nor does the F.B.I.—even though Hoover normally wrote a memo following a visit to the White House. We do know the meeting went badly. O'Donnell, interviewed years later, would say only that the president eventually lost patience. "Get rid of that bastard," he hissed to his aide. "He's the biggest bore."

Since the mid-70s, when a Senate inquiry probed the nation's darker intelligence secrets, the encounter has had a special significance. Hoover sat down with the president armed with dirt more explosive than even he was used to— much of it, ironically, obtained thanks to Robert Kennedy's pursuit of Mafia boss Sam Giancana.

Hoover had learned, even before Eisenhower left office, that there was a plot to kill Cuban leader Fidel Castro and that Giancana was somehow involved. Early in the Kennedy presidency Hoover discovered Giancana was working with the C.I.A., and by March 1962 he knew that Judith Exner, who was in touch with Giancana, was one of the president's lovers. He knew, too, of Giancana's threat to "tell all" about the Kennedys and was aware, from a recent wiretap, that Giancana and Roselli had discussed obtaining a "really small" receiver for bugging conversations. In that same discussion they had spoken of "Bobby" and when he would next be in Washington.

Judith Exner reveals that Hoover indeed brought her name up that day. "Jack called me that afternoon," she said. "He told me to go to my mother's house and call him from there. When I did, he said the phone in my apartment wasn't safe. He was furious. You could feel his anger. He said Hoover had told him I was a friend of two men in the underworld and that he knew I had been at the White House."

According to Exner, there was something even more damaging to hide. Early in the presidency, Kennedy had repeated his folly of the election period—by meeting again with Giancana. The new contacts, Exner said the president told her, "had to do with the elimination of Fidel Castro." Kennedy, she claims, also used her as a courier, on some 20 occasions, to carry confidential envelopes to Giancana.

Most historians now accept that the Kennedy brothers were involved in the Castro plots. We know that after the Bay of Pigs debacle they no longer trusted the C.I.A. It is therefore possible that, given his existing relationship with Giancana, the president may have chosen to deal directly with the mobster about Castro murder plans.

According to Exner, the president said the envelopes he sent to Giancana contained "intelligence material" to do with the plots. The envelopes were sealed, however, and she never saw the contents. Whatever they contained, John Kennedy was playing a horrendously dangerous game. Giancana had hoped that his help— first in getting the president elected and then with the Castro operation—would be rewarded with federal leniency. Yet Robert Kennedy's onslaught on organized crime did not merely include Giancana among its targets, but singled him out for especially intensive harassment.

It is not clear how fully Hoover understood the Giancana scenario in March 1962, only that he knew plenty and told the president so. "My impression from Jack," Judith Exner said, "was that Hoover had intimated to him that he knew I had been passing material from Jack to Sam." According to Cartha DeLoach, Hoover returned from the meeting saying he had told the president he knew "a great deal" of what was going on.

The president could not risk trying to dump his F.B.I. director. The Giancana mess aside, Hoover was now armed with knowledge of a battery of other Kennedy follies. Even before the March confrontation, Hoover had let the president know he knew about the use of prostitutes during the 1960 convention.

As if this were not enough, there was the Hollywood connection—the president's alleged involvement with the actress Angie Dickinson, and Marilyn Monroe's affairs with both brothers.

Dickinson is said to have become one of John Kennedy's lovers sometime before the inauguration. "Angie and J.F.K. disappeared for two or three days in Palm Springs during the period before J.F.K. assumed office," recalled photographer Slim Aarons, a Kennedy friend. "They stayed in a cottage and never emerged. Everyone knew about it. ' '

An account of how Hoover found out about Angie Dickinson comes from a former F.B.I. agent whose squad liaised with the Secret Service. "It happened," said the agent, who asked to remain anonymous, "when Kennedy was on the West Coast on political business. He flew from Burbank Airport to Palm Springs by chartered aircraft, with Angie Dickinson on board, and they took a detour—via Arizona. When they did get to Palm Springs, Kennedy got off alone, I guess to stop the press seeing Dickinson.

"The problems came later. The plane on that trip had been an executive aircraft with a stateroom: A crew member, who was employed by Lockheed, had bugged the stateroom and taped the conversation. And afterwards he tried to use the tape, anonymously, to extort the president for a large sum of money. His letter was intercepted by the Secret Service, and they called the F.B.I. Our goal was to get that tape back. Find it, get it back. No publicity. We checked on the airplane's crew, and this crew member was kind of shady. So when he was abroad on a trip we bribed the manager of his apartment to let us in.

"We found the tape recording hidden in the wall, near an electric socket. We took it and we resealed the goddamn thing so the guy wouldn't even know at first it was gone. The Bureau gave us very exact orders after we found the tape. They didn't want it mailed. They wanted it sent by personal messenger to the director. We talked to Lockheed and they fired the guy. There was no prosecution, to keep it quiet. And that was that. But Hoover had the tape."

Even as Hoover received his information on Dickinson, he was assiduously monitoring yet another dalliance—with the most famous Hollywood beauty of them all.

There is now no doubt that Marilyn Monroe and John F. Kennedy had an affair of sorts which continued sporadically into the first and second years of the presidency. Monroe was smuggled into Kennedy's suite at New York's Carlyle hotel, even on board Air Force One, disguised in a black wig and sunglasses. Such escapades would have been dangerous at any time, and Monroe's state of mind made them especially so.

In 1962, Mafia boss Sam Giancana was still under constant pressure from the Justice Department. According to his half-brother Chuck, he now hired surveillance experts to collect dirt on the president and his brother. If collaborating with them had failed to help, the mobster intended to try blackmail.

The president's brother-in-law Peter Lawford had long since been under surveillance on the orders of someone else—Hoover. The sound specialist who installed the bugs is still operating today and has revealed his role only on the formal understanding that his name not be used. "The job at the Lawford house," the source said in 1991, "was done for the Bureau, through a middleman. I installed the devices on F.B.I. orders. They were in the living room, the bedrooms, and one of the bathrooms. An intermediary for Hoover came to me to arrange the installation, I guess at the end of the summer, in 1961. The formal reason given was that Hoover wanted information on the organized-crime figures coming and going at the Lawford place. Sam Giancana was there sometimes. But of course the Kennedys, both John and Robert, went there, too.

"Hoover's intermediary told me that, as attorney general, Robert Kennedy had given strict orders that the house was not to be bugged. But it was covered, on Hoover's personal instructions. Jimmy Hoffa did get one of the Kennedy-Monroe tapes, but only because it was leaked to him by one of the operatives. He wanted to make a buck, and Hoffa's people paid $ 100,000— a lot of money back then. But that surveillance was commissioned by the F.B.I., and almost all the tapes went to the F.B.I. J. Edgar Hoover had access to every goddamned thing that happened at the beach house, including what happened when the Kennedys were there, for nearly a year. Draw your own conclusion."

One of the men who monitored the bugs at the Lawford house was private investigator John Danoff. He told how, during the presidential visit in November 1961, he listened in as John Kennedy and Monroe made love. For Hoover, tapes of scenes like this were just the beginning of the harvest.

On February 1, 1962, Monroe met Robert Kennedy for the first time, at a dinner party in the Lawford house. Later that night, the actress was to tell a friend, she and Robert talked alone in the den. In characteristic fashion, she had prepared questions of topical interest and asked whether it was true that J. Edgar Hoover might soon be fired. Robert replied that "he and the president didn't feel strong enough to do so, though they wanted to."

According to the man who had installed the bugs, that conversation would have been picked up by the hidden microphones. For Hoover, reading the transcript in Washington, Kennedy's words must have held some comfort. He now knew, for sure, from the mouth of one of the brothers, that the Kennedys were afraid to dismiss him—for the time being. That gave him all the more reason to go on watching, to keep on piling up compromising information.

Hoover, therefore, would have known about Robert's comments on his future, and about the president's sex activities with Monroe at the Lawford house, well in time for his lunch at the White House in March 1962. Yet whether or not Hoover mentioned Monroe that day—along with Judith Exner—John Kennedy blithely saw the actress again within 48 hours, on a trip to California.

In Washington in the weeks that followed, the tension between Hoover and the Kennedys continued. Robert Kennedy and Hoover now rarely cooperated with each other on anything.

The Monroe saga, meanwhile, took a strange turn. John Kennedy saw the actress once more, on May 19 in New York, but apparently never again. Robert, however, soon followed his brother into the actress's embrace. He, in turn, then tried to distance himself, but too late to avoid being drawn into Monroe's psychiatric collapse. And too late to avoid falling into a double trap—the surveillance ordered by the criminals, Giancana and Hoffa, and the web spun by Hoover.

On June 27, according to Monroe's housekeeper, Robert Kennedy arrived at the actress's home alone, "driving a Cadillac convertible." A memorandum from the Los Angeles agent in charge, William Simon, landed on Hoover's desk within days. "I remember it coming in. I was shocked," recalled Cartha DeLoach. "Simon reported that Bobby was borrowing his Cadillac convertible for the purpose of going to see Marilyn Monroe." From then on, agent sources say, the attorney general's California comings and goings were effectively under Bureau surveillance.

Heavily censored F.B.I. documents indicate that during the June visit Monroe had lunch with the attorney general at Peter Lawford's house. Their conversation included a discussion about "the morality of atomic testing." At that critical time in the Cold War, anything Robert Kennedy said about such matters would have been of interest to Communist intelligence. For Hoover, aware that Monroe had numerous left-wing friends, the development meant that his gratuitous snooping could now be justified as an authentic security concern.

On Saturday, August 4, Monroe was found dead. The autopsy report gave the cause of death as "acute barbiturate poisoning due to ingestion of overdose," and the coroner decided it was a "probable" suicide. Others have theorized that the overdose was not taken by mouth but administered by someone else—perhaps by injection, perhaps rectally.

Sam Giancana's half-brother Chuck claimed in 1992 that the Chicago mobster had Monroe murdered so that "Bobby Kennedy's affair with the starlet would be exposed." A mass of testimony, supported in the 80s by Peter Lawford, suggests that Robert Kennedy flew to Los Angeles on August 4 and had an ugly showdown with Monroe. The row drove Monroe to hysteria, and her psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson, had to be called. Years later, he confirmed privately that Robert Kennedy also was present the night the star died. To complicate matters, a crumpled piece of paper, found in Monroe's bedclothes, bore a White House telephone number.

A remarkable cover-up followed. The problem of that scrap of paper, and many other embarrassments, simply evaporated. Records of Monroe's telephone calls were made to disappear, in part thanks to Captain James Hamilton of Police Intelligence, a longtime friend of the attorney general's. It was not the police, however, who retrieved the records of Monroe's last phone calls. As a reporter discovered at the time, they had been removed from the headquarters of General Telephone by midmoming on the day after Monroe's death. And, according to the company's division manager, Robert Tiarks, they were taken by the F.B.I.

A former senior F.B.I. official, then serving in a West Coast city, confirms it. "I was on a visit to California when Monroe died, and there were some people there, Bureau personnel, who normally wouldn't have been there—agents from out of town. They were on the scene immediately, as soon as she died, before anyone realized what had happened. I subsequently learned that agents had removed the records. It had to be on the instructions of someone high up, higher even than Hoover."

Meyer Lansky claimed that Hoover was no threat, that he had been "fixed."

The former official understood at the time that the orders came from "either the attorney general or the president." "I remember the communications coming in from the Los Angeles division," said Cartha DeLoach. ' 'A Kennedy phone number was on the nightstand by Monroe's bed." Monroe's death, it seems, at last brought home to the president the scale of the risks he was running. The White House phone log shows he took a call from Peter Lawford at 6:04 California time on the morning Monroe was found dead, an hour after Lawford had hired security consultants to go to Monroe's house and remove all evidence of the brothers' affairs with her. Another of John Kennedy's lovers, Judith Exner, called the White House twice the next day—once in the afternoon and again in the evening. A note in the log indicates that Kennedy was in conference, with the scrawled addition "No." The perilous Exner liaison, it seemed, was ending at last.

If mobsters had hoped to use the Monroe connection to destroy Robert Kennedy, they were thwarted by the successful cover-up. That cover-up, however, worked largely thanks to Hoover. By grabbing the telephone records on their behalf, he made the Kennedys more beholden to him than ever.

On August 7, just 48 hours after that favor, Robert Kennedy did something remarkable. A few hours earlier, W. H. Ferry, vice president of the Fund for the Republic, set up by the Ford Foundation to promote civil liberties, had lambasted Hoover's scaremongering about Communism as "sententious poppycock." Robert Kennedy, we know, shared that view. Now, however, he uncharacteristically leapt to Hoover's defense, effusively praising his stance on Communism. "I hope," he said piously, "he will continue to serve the country for many, many years to come."

J. Edgar Hoover would indeed remain in office, for another 10 years—long after both Kennedy brothers had been assassinated. His own last day alive, by a great irony, would coincide with May Day, the workers' holiday celebrated by the left, which he had struggled all his life to suppress. It was 1972, and he arrived at work alone, without the ailing Clyde Tolson.

That last day was not a pleasant one for the director. In the morning, in his Washington Post column, Jack Anderson offered revelations about F.B.I. dossiers on the private lives of political figures, black leaders, newsmen, and show-business people. Hours later, in a carefully timed appearance on Capitol Hill, the columnist promised to prove it. "The executive branch," Anderson testified to a congressional committee, ' 'conducts secret investigations of prominent Americans.... F.B.I. chief J. Edgar Hoover has demonstrated an intense interest in who is sleeping with whom in Washington.... I should make clear at this time that I am not offering hearsay testimony. I have seen F.B.I. sex reports; I have examined F.B.I. files. ... I am willing to make some of these documents available to the committee."

These were astonishing claims in 1972, and the F.B.I. corridors were abuzz with talk about Anderson all day. His testimony, however, was only one in a salvo of new attacks. A few days earlier, Hoover had obtained advance copies of two books about him. Citizen Hoover, by Jay Robert Nash, was a savage critique of Hoover's entire career. Americans, Nash wrote, no longer knew what to make of Hoover. He was both "benefactor and bully, protector and oppressor, truth-giver and liar." Nash continued, "The truth is the F.B.I. of our collective memory never really existed outside of the very fertile and imaginative mind of its eternal Director. ... To him, all high adventure was possible in the cause of Right, all moral victories over obvious evil inevitable, so long as faith in the all-encompassing power of his good office was absolute."

The second book was more damaging. In a daring expose called simply John Edgar Hoover, reporter Hank Messick hinted at the dark truths behind Hoover's compliant attitude toward organized crime, and the relationship with Lewis Rosenstiel, which placed Hoover close to top mafiosi. Secret F.B .1. intervention no longer cowed publishers as it had in the past. These books were going to be published whether Hoover liked it or not.

Hoover stayed at work until nearly six that last day, then went to Tolson's apartment for dinner. He probably arrived home about 10:15 P.M., to be greeted by his two yapping cairn terriers. Hoover liked to have a nightcap, a glass of his favorite bourbon, Jack Daniel's, poured from a musical decanter. When raised, the decanter tinkled "For He's a Jolly Good Fellow," and Hoover was fond of it.

If the director did have such a quiet moment that night, it was reportedly ruined by an unwelcome telephone call. Later, Helen Gandy, Hoover's longtime secretary, would claim that somewhere between 10 and midnight President Nixon called Hoover at home. His purpose, Gandy said, was to tell Hoover, not for the first time, that he should quit. Afterward, Hoover phoned Tolson to talk about the call, and Tolson subsequently told Gandy.

If the Gandy account is accurate, Hoover must have gone to bed feeling shattered. He would have walked into the hall, past the bust of himself waiting to greet visitors, past the pictures and inscriptions that spoke of 59 years in government service. Then he would have climbed the stairs, passing an oil painting of himself on the landing, to the master bedroom with its great maple-wood four-poster.

There, early the next morning, Hoover would be found dead, lying half-naked on the floor. "Jesus Christ!" President Nixon reportedly exclaimed when he heard the news. "That old cocksucker!" Aides were promptly ordered to secure Hoover's files, "to find out what's there. . .where the skeletons are." In fact, Hoover loyalists spirited away many of the most sensitive dossiers and secretly destroyed them.

Nixon gave J. Edgar Hoover a state funeral and praised him as an American hero. Ronald Reagan, then governor of California, said, "No 20th-century man has meant more to this country than Hoover." Soon enough, however, it became clear that Hoover had long abused his office, undermining the basic American freedoms he had claimed to hold dear. Yet 20 years after his death, in spite of the compelling evidence that he was a force for great evil in the nation's life, Hoover's name still gleams, in letters of gold, high on the walls of F.B.I. headquarters in Washington.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now