Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHELLO!'S ELUSIVE CONQUISTADOR

Eduardo Sánchez Junco is Madrid's Citizen Kane, a powerful and mysterious media tycoon whose frothy ¡Hola! and Hello! magazines reign over the newsstands in Spain and England. Will Don Eduardo bring his glossy empire to the United States?

LUISITA LOPEZ TORREGROSA

Media

In the baroque world of Madrid's upper class, one of Europe's most snobbish circles of dowagers and grandees, the name of Eduardo Sanchez Junco, the "Citizen Kane of Spain," provokes awe. For Don Eduardo, the owner, publisher, and editor of Spain's largest weekly, jHola!, and England's best-selling Hello!, reigns as the chronicler of high society in a country where aristocracy is a national obsession, where anyone-who-is-anyone holds a title—la condesa this, el marques that—and where life revolves around fashionable restaurants, weddings and debuts, summers in Majorca, and the society pages.

But Eduardo, a patrician self-made millionaire at the age of 50, remains in the shadows, shielding himself and his family—which holds sole control of the Sanchez publishing empire—from the headlines. Few untitled people, in fact, are familiar with his name and face, though millions know the puff pieces and artless photographs of royalty and celebrities in jHola! and Hello!

Don Eduardo's invitation to meet him at his home, an unpretentious 1960s apartment in a stylish district of Madrid, was unusual—he normally receives guests in the magazine offices a floor below. He grants face-to-face interviews only rarely, and he is visibly uncomfortable, squirming into a corner of a plump pearl-gray sofa in his living room.

While across the Atlantic magazine publishers and editors thrive in the limelight, becoming at times bigger than the publications they command, Eduardo— as everyone calls him—eludes publicity, preferring the pastoral seclusion of his 5,000-acre farm in Burgos to the frenetic chitchat of Madrid's social life. "We have no secrets, nothing to hide," he assures me in a firm, measured tone. "You have to understand, that is our character. We want our magazine to stand on its own. We don't want to distract from it by being interviewed and photographed.... I would like to remain anonymous. I feel no need to be popular. It isn't necessary. Discretion is essential to our work."

Short and handsome, with an Old World charm that veils a calculating mind, Don Eduardo crosses his arms over his faded blue polo shirt and leans back. He seems bigger than he actually is, and daunting, an impresario accustomed to giving orders and imposing his will. Powerful, deeply lined, and framed by graying sideburns, his face has a fluorescent-light cast to it, and although he is a fanatical tennis player, he has developed the pudgy midriff of the deskbound.

"The key to our success," he says, "is in the news of the week, and that is unpredictable. Yes, the package matters. The mix. The pretty pictures. The cover. But it's the news, die information we give inside that no one else has, that is at the heart of the magazine."

His father, Antonio Sanchez Gomez, a newspaper editor who created Hola! with a ruler and a pencil in a small room in the family flat in Barcelona 50 years ago, "was a genius," declares Don Eduardo. "He understood what the reader wanted. In 1944 his idea was quite original, a precursor of a kind of journalism that has been broadened over the years. When he started, he called it jHola! Semanario de Amenidades [A Weekly of Amenities]. Think about it. He already understood the use of pictures, of entertainment. Sometimes he used to say that jHola! captures the froth of life—nothing that is heavy or deep or depressing."

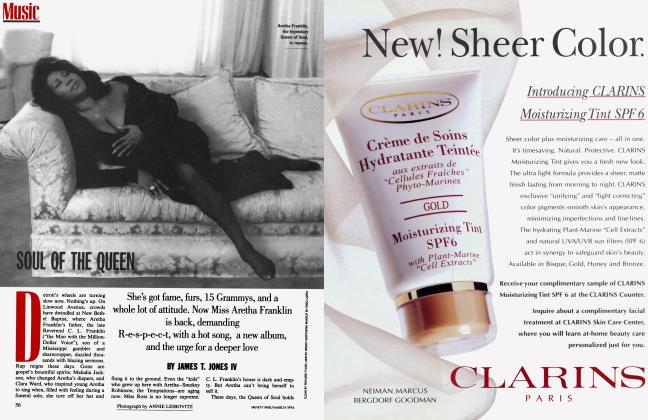

With Disneyesque magic, the formula works. There are pages and pages of color pictures of the rich and famousroyalty, movie stars, and fashion models at weddings, baptisms, funerals, debutante parties, and affairs of state. Visually dominated, the magazine adds reportage that runs to inanities (People magazine is cerebral by comparison). The reader-friendly Q&A's create an artificial intimacy, a gauze thrown over reality. It's all geared to make people look good and feel good.

The secret of jHola!'s appeal lies in the pictures. At a glance, the photos seem harmless and boring, but a closer look reveals famous faces as they are seldom seen in fancier magazines, where the photographs are often staged. jHola! and Hello!—which are not identical, since each caters to a different culture and language—are not unlike a family album of snapshots taken by a close relative.

A recent issue of Hello! carried nine pages and 20 pictures of the trip Prince and Princess Michael of Kent took on the Eastern and Oriental Express from Singapore to Bangkok. There is the princess, in her green and white head scarves and tropical whites, fanning herself while holding a bouquet and smiling at shy Singaporean children dressed up in local costumes; there is the princess fanning herself on a trishaw ride; there she is again, fanning herself and singing, mouth wide open, aboard the train. Her husband, in double-breasted pastels, smiles through his beard, perhaps unaware that in these photos he comes across as the prototypical colonial governor.

"iHoh! captures the froth of fife— nothing that is heavy or deep or depressing."

"We don't believe in opinion journalism," explains Don Eduardo, "in judging the values and attitudes of people. The images always say more than the protagonists. We do look for that something in the pictures."

It's not easy keeping the magazine safe for 12-year-olds while at the same time toasting royals and celebrities whose real lives are often scandaland tragedyridden. But Don Eduardo pulls it off. The magazine projects a rosy universe where lives have happy endings. Even the few funerals it covers are positive, commemorative rather than mournful.

Faithful to an iron rule set long ago by his father, Don Eduardo will never embarrass a subject, will never offend a reader, will never wallow in gossip, and will not run screeching headlines. He will seek and print firsthand confessions—if Princess Di wanted to sit down and talk about her bouts with depression and life with Charles, Don Eduardo would happily publish it. But he won't print secondhand reports, lurid rumors, or sexual dirt, his reporters tell me, not without a tinge of irritation. "I knew all about Diana and Charles before it broke," one says, "but Eduardo wouldn't listen to it." And so, the sludge of journalism, even the discreet forms of trash and sleaze that juice up the news around the world, finds no home in sweet Hello!

Take, for instance, the recent interview in Hello! with the onetime wife of the late actor Raymond Burr, which reveals that Burr lived with a man for 30 years. The magazine resisted the titillating headline—"Perry Mason Was Gay." Instead, it went dainty: "Revealing the Secret She Kept for 45 Years—Raymond Burr's Widow Isabella Talks for the First Time About Her Marriage to the Perry Mason Star."

Don Eduardo concedes he has to shape the information he gives. "I have to set limits. More often it's the tone that's important, the style we use to convey the information. Our success lies in the way the readers relate to the magazine. It's not great, transcendental journalism. It's entertainment."

With promises of decorum and mildmannered articles, he scores some bigtime coups—an exclusive on Mia Farrow in Ireland (which beat Paris Match by a few weeks), an intimate spread on the Duke and Duchess of York, exclusive photos of Elizabeth Taylor's private wedding.

These are the sorts of eye-popping pieces that the Sanchez family has peddled so successfully that jHola! is now the biggest-selling weekly in Spain, with a paid circulation of 650,000 and estimated annual advertising revenues of $48 million. Its sister publication, Hello!, started five and a half years ago in London, has taken England by storm. It has shot up from 180,360 readers to almost half a million—with a following that ranges from working-class readers to the affluent audience advertisers and publishers crave—and it is believed to make about $2.2 million a year. An unlikely urchin, coming from the provincial Continent, Hello! has grown faster than any other British magazine ever—and it has done so without trading on scandals, without scurrilous gossip, and without tits-and-ass vulgarity.

"There has never been anything like Hello!" says columnist Mary Kenny in London's Sunday Telegraph. So intrigued is Kenny with the Hello! mystique that she has taken the trouble to trace its success to semiotics, the philosophical study of communication through signs and symbols. She professes that "it is about the Catholic return of the visual to what has been a fundamentally Protestant, word-oriented culture."

I ask Don Eduardo about his plans to produce an American edition of Hello!, which he hopes will pop up on the newsstands in big U.S. cities such as New York, Los Angeles, and Miami this year. (jHola! already has a following among the large Latin-American community in South Florida.) "The decision to go is not final," he says. "When we are ready to announce it, we will."

In the prickly world of publishing, where a tiny leak can deflate a deal, the longrunning negotiations to find an American partner have taken on an aura of great mystery. Like Don Eduardo himself, who gives away no details, the other principals involved in the discussions are secretive. According to New York publishing sources, the prospective partners have included Meigher Communications, Hearst Corporation, and the ubiquitous Rupert Murdoch. "Eduardo would be comfortable with Murdoch," says an insider who spoke on the condition of anonymity. Murdoch certainly has the organization and distribution system Don Eduardo needs to start up in America, but it seems unlikely, although not impossible, that Murdoch and the one-man band Sanchez Junco could easily share power.

The negotiations between Don Eduardo and S. Christopher Meigher III, the C.E.O. of Meigher Communications, go back more than a year. They eventually stalled because Don Eduardo was reportedly unwilling to cede editorial control and commit enough money. "There was a gap in investment," reveals a source. But Meigher still foresees big things for Don Eduardo and considers himself an admirer of the man and his magazine. "Eduardo has something unique," he says. "He would add a new energy to the U.S. publishing environment. He has a rare blend of editorial vision and commercial acuity and intuition."

The official line at Hearst headquarters in New York is press-release terse: "We are no longer involved in the project." Yet a source outside Hearst who is familiar with the maneuvers claims that the company is not entirely out of the picture and that a team of executives traveled to Madrid in December to press its case with Don Eduardo. Those who know Don Eduardo's thinking, however, confide that his attention has lately been captured by Conde Nast Publications, the publisher of Vanity Fair. "He definitely wants to go with Conde Nast if something can be worked out," a source told me. S. I. Newhouse Jr., chairman of Conde Nast Publications, says, "I talked to him recently. I have always been very impressed with the magazine. However, we have so many magazines that we felt it would not be in the best interests of Sanchez to take him up at this time."

"The true [Spanish] high society is made of 20 families. It's like the end of an eracomipt and immoral."

Some observers believe that Don Eduardo will in the end choose a low-risk course, launching the American Hello! entirely on his own, from Madrid. "My guess is he'll start slowly," says a source, "and expand on a gradual basis."

In any case, the news that Hello! may come to America has roiled the fanzine industry. The supermarket tabloids National Enquirer and The Star are known to have considered starting up a Hello!like magazine. Time Warner is test-marketing In Style, a People-magazine spinoff, in what seems to be an attempt to pull the rug from under Hello! But one publishing expert says that the Time Warner magazine may be overmatched. "In Style is a monthly," he says. "Hello! is a weekly. The people over at In Style are pleased with the result so far, but they are not overwhelmed. In Style doesn't capture Hello!"

An American launch of Hello! would mean that Don Eduardo would occasionally have to leave the comforts of home to attend to business 3,500 miles away. (He oversees Hello! in Madrid, where all the copy and photographs are faxed or flown to him. He edits it, lays it out, and sends it to the printer, and the finished product is then sent back to England for distribution—a cumbersome process that may not work across the Atlantic.) To make things more troublesome for him, he dislikes planes, speaks little English, and barely knows New York.

He is also worried that the American market may prove costly to conquer. "There's a limit financially to what we can do," he says carefully. "I fear the risk. It's a big gamble." Even with his extraordinary success in England, Don Eduardo doesn't assume that Hello! will make a big splash in the United States. "We would prefer to sneak in," he says, half jokingly. "That way, if we fail, we can sneak back out and no one will know."

He is no streetwise and worldly Rupert Murdoch, but he is an adventurer— he took a Spanish product to England in the middle of a recession and succeeded—and a visionary who hopes his magazines last 150 years. He can't resist a challenge, even when it means venturing into a vast and unfamiliar new market like the U.S. "I don't know why I would do this," Don Eduardo wonders aloud. "It's not for personal aggrandizement. It's not for financial gain. I am very comfortable economically. It must be something I have to do. It's professional necessity." Then he breaks into a boyish smile. "Well, it's America. America is the dream, isn't it?"

Don Eduardo Sanchez Junco has lived with jHola! all his life. "It's like my sister," he says. "I've lived jHola! since I was a child. It's my family." An only child, Don Eduardo was just a year old when his father started the magazine, and his mother remembers baby Eduardo crawling beneath the table where she sat with her husband, piecing together jHola! with scissors and paste. It was an inauspicious beginning. "My father would come home from work around 3:30 in the afternoon and sit down with my mother to plan the magazine," Don Eduardo recalls. "They did it all alone." In time, Don Antonio left his job at La Prensa, an afternoon newspaper, and put his energy and savings entirely into the magazine. "He put all his money, which wasn't much, into it. It was my parents' labor of love."

We're meeting a second time, in the den of his apartment, a dim room furnished with a silver-gray sofa, a piano, a TV set and VCR, and a bar with two low wood-and-leather chairs. Behind the bar, glass shelves hold a collection of porcelain beer mugs, and small 19th-century canvas paintings of landscapes and farm scenes hang on gray-papered walls. It is late afternoon, and Don Eduardo is in a hurry. He has phone calls to make and his regular Tuesday-night tennis game. But he takes time to pour an espresso and talk about the magazine.

As jHola! grew in circulation, he says, Barcelona became inconvenient, too removed, and the Sanchez family moved to Madrid, from which distribution of the magazine across the peninsula was easier. Then, in February 1984, Don Antonio died. "It was unexpected," Don Eduardo says with lingering sadness. "It was a Monday, the day we close the magazine, and he had been working here, in this same building. My parents lived next door to us. He had been closing pages and signing them off on the rundown sheet. Suddenly he had a heart seizure. It dawned on me later that his initials were on the first pages that went to press and mine on the final pages. I saved that sheet and have it framed. It is to me so symbolic... that there is no line that divides us."

It's time now for his tennis match, at a private club, but before he leaves to change clothes he brings in his mother, who lives in a connecting flat. Dona Mercedes enters the room nervously. She has rarely given an interview and feels embarrassed talking about herself, but she tells me about her 42 years of happiness with her husband, whom she met when she was 17. "He gave me a pen," she recalls. They married when she was 20 and he 30, and not once in their four decades together does she remember their being apart.

"I wanted many children, 20, but instead we had this magazine," she says. "This is our daughter." After Don Antonio died, Don Eduardo insisted that she keep working on the magazine, and despite her protests her influence is enormous. "She has her kind of taste," says jHola! correspondent Naty Abascal, "and she has a lot to say about the pictures and the copy."

Though the Sanchez empire spans 92 countries, "they do all the layouts by hand. Doha Mercedes and Don Eduardo do it all."

Formal but affectionate and striking at 72 in a finely cut foggy-gray suit set off by her coiffed blond hair and her blue-green eyes, Dona Mercedes wears almost no jewelry, only a single strand of pearls, and an aquamarine Hermes scarf. While chic Madrilenas might shrivel without their designer baubles and gold chokers, she makes her statement quite simply, a Castilian Katharine Graham.

"My inner loneliness is enormous," she says, her eyes moistening as she recalls her husband. "So I will stay on with this thing of ours. It is like being at his side.... My God, why isn't he here to see all this? How beautiful it would be to have him here."

I ask her if she will go to New York when Hello! debuts. She remembers her last trip there; she stayed at the Pierre. "I was so in love with New York," she says, "that now I'm afraid the enchantment will be gone." She wants to publish Hello! in the United States, she assures me. "In life there are steps to climb," she recalls her husband saying. "I believe that, yes, we must do this. This is a step that he would have climbed."

Now she wants me to meet her granddaughter Carmen, a 22-year-old with long darkbrown hair and dark eyes, Don Eduardo's oldest child. Eduardo and his wife, Carmen, who was a journalism student and is involved in the magazine, have two other college-age children, Mercedes, a 20-year-old agronomy student, and 18-year-old Eduardo, who is studying journalism. Daughter Carmen, the newest star in the Sanchez family, has five bylines in the recent fashion issue, including interviews with Gianni Versace, Oscar de la Renta, and Valentino. A wisp of a woman in faded jeans and a white Tshirt, she is totally unassuming and seems chagrined when Dona Mercedes shows me her articles and boasts that Carmen wants to get a master's degree at Harvard. Carmen can barely speak for herself because she is recovering from minor throat surgery, but she manages a wan smile and, diffident like her father, whispers, "I hope so."

It is now past eight o'clock, and my visit is almost over, but while we are talking Don Eduardo saunters in for a moment, wearing sweatpants and scuffed tennis shoes. He is warmly solicitous of his mother and, to my surprise, hugs me as he leaves. Dona Mercedes turns to me and says softly, "My son is everything a mother could ask. My son is the soul of everything."

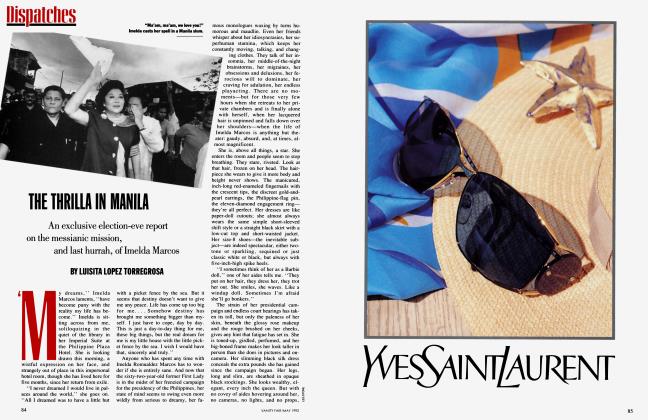

he Marquesa de Varela flings open the door of her bedroom, an apparition in head-to-toe black. "What a life this is! The life of a journalist!" she exclaims with the flourish of a grand entrance, her hands fussing around a pair of earrings. The marquesa, who procures top celebrity interviews for Hello!, has just arrived from Jordan, where she visited with royalty. Her luggage, a couple of oversize duffel bags, rests on an Art Deco-ish modular sofa in her cramped living room.

In two days she will fly to London for the wedding of Viscount Linley and Serena Stanhope, and then she is off to New York, where, she tells me, she is looking to buy an apartment. It's all like that, a maddening swirl. She sits down for a nanosecond, her hem riding up to mid-thigh, behind a coffee table laden with a mass of papers, letters, faxes, and copies of Women Who Run with the Wolves and The Bridges of Madison County. A frumpy maid is dusting, and it turns out there is nothing to drink in the kitchen. Before the marquesa rushes me out of the apartment for an espresso at a nearby cafe, she hands me a picture of one of her daughters, a stunning girl with onyx eyes the size of marbles. "You know, I'm a grandmother," she reveals with a broad lipsticked smile, her greenish eyes flaring wide, anticipating the compliment that must follow— that she looks too young to have grandchildren.

Twice married and twice divorced— her title comes from a Spanish marques whom she divorced several years ago— the marquesa, who insists I call her Neneta, takes me on a whirlwind tour of her life. She has a daughter in Spain, another in Uruguay, and a young son who often travels with her. She was born in Uruguay, nee Maria Julia Marin, nicknamed Neneta, 48 years ago, the daughter of a strict Spanish father and a Genoese mother. She says she owes her strong character to her father, who is dead, and sketches an idyllic childhood of horses and far-flung travels to Biarritz and Paris followed by dismal marriages to a wealthy Italian businessman and a titled Spaniard. After her last marital debacle, she vanished from society. But a year ago a radical change happened. She had to undergo breast surgery, which turned out well, but the scare led her to revise her life, to come out again in society and enjoy friends and work.

"I can thrive alone, but I have a pride that kills. To be a Latin-American woman is not easy," she sighs, shaking her head. For the past 11 years she has worked for jHola!, and now she is based in London, where she is the number-one "fixer" for Hello!, the woman—a persistent rumor has it—with the Louis Vuitton suitcase filled with cash to pay for interviews. She denies all that with vehemence, obviously insulted. "Look at me. I hate labels." She fingers her snug black knit dress and sticks out her lacedup black suede high-heeled ankle boots. "This little skirt I bought at Sears in Miami. The shoes are Donna Karan. It's the herd that buys Louis Vuitton, and those Chanel bags."

The Vuitton suitcase is the least of her worries. The publishers of Hello! have been reprimanded by the Press Complaints Commission of Britain for paying for an interview with Darius Guppy, a quasi-aristocrat who is serving eight years in jail for fraud. The magazine admits paying a relative of Guppy's and an agent to acquire the interview, but claims it did not know it was violating the British press-ethics code. In Spain, paying for interviews is commonplace, and such things are taken in stride. There are other rumors, denied by the marquesa, that she got the exclusive on Elizabeth Taylor's wedding by promising to donate money to a charity and that she paid off the Duchess of York for a 46-page spread. "We do pay some people," she has admitted. "But all the magazines in the world pay, for weddings, for baptisms.... It's all envy. They are going after me because I get these people."

She does confess she is deeply unhappy in London—"I get no support from the Hello! staff there, and the English are impossible." As for Spanish society, she shrugs it off. "The true high society is made of 20 families. It's like the end of an era—corrupt and immoral."

These days Spain has become just a stopover for her, a chance to check in with Don Eduardo and see her daughter. "Eduardo is not close to anyone," she claims, including herself. "He's not close to his mother. He's not close to his wife. He has a very complex personality. ... He changes his mind constantly. He's always adding pages or cutting back at the last minute. We do everything on the run, and he is the only one who can make decisions. He has all the power."

In the jHola! stable of stars, none shines like Naty Abascal, described aptly as "classic and exotic" in jHola!'s special 1993-94 issue on alta costura (high fashion), presided over by Don Eduardo's mother. "Doha Mercedes has her little drawings, her little dolls, and she sits next to him every week in this little room and they put out the magazine," says Naty, a fashion arbiter and famed model (she was once photographed by Avedon and hangs around with Valentino and the Milan gang) who wants the magazine to venture farther out on the fashion scene.

We meet when she strides queenlike into the Hotel Ritz in Madrid to have lunch. Slender and very tall, an oliveskinned Audrey Hepburn, she is monochromatically dressed in a tweedy jacketand-skirt suit of the faintest brown, an Hermes scarf wrapped around her elongated neck. Air kisses out of the way, she puts her Hermes beige leather bag down on the hotel's handloomed carpet and unfurls her scarf. Her eyes, lined in black, are the shade of Godiva chocolate truffles. But it is the shape of her nose—Roman, aquiline, with a photogenic bump—that dominates the face.

Naty has been with jHola! just a year, jetting from Madrid to Milan to Paris to New York to follow the fashion trail. She's a natural force in a scene of hyperegos and outre artifice. She is separated from a duke and she rues that she is now alone, taking care of her two boys, and that her frenzied life has the twists and turns of a telenovela.

She is too busy relating the dramas of her life to speak about jHola! But later, after she and I spend almost an hour at the Hermes boutique on the Calle de Ortega y Gasset while she tries on virtually every scarf in the shop, she takes me to jHola!'s office, on the first floor of Don Eduardo's apartment building. The office is not usually accessible to the outside press, and the front door is locked much of the time. A visitor might easily miss the entrance, which has only a small goldplated sign with the word jHOLA!

The house of jHola! is hardly a palace. One would think this is a struggling little magazine. A dozen or so trophies and plaques of encomiums are piled on a table in a hallway, but there are no gallery posters or blowups of magazine covers brightening up the walls. There are a few official photographs of King Juan Carlos, and a photograph of Don Eduardo's father, Don Antonio, statesmanlike in his 70s, gray hair combed back, tie firmly knotted, jacket buttoned up, eyes staring dolefully at the camera.

The room where jHola! comes together every Monday resembles an old-fashioned newspaper office, crammed floor to ceiling with books, trash from previous issues, sketches, and layouts. A calendar and the photograph of Don Antonio hang on one wall. On this late afternoon the place is gloomy and quiet, with only the white noise of a fax machine in another room breaking the silence. A rectangular art table occupies most of the room, which is strewn with the debris of publishing—notes, tacked-up memos, drawings. "They do all the layouts by hand," Naty says. "There are no computers, only that little projection screen to see the photos. Dona Mercedes and Don Eduardo do it all."

A handful of writers on the fourth floor, where jHola! has expanded into a set of barren offices, write captions and headlines, but Don Eduardo minds every detail, from the cover to the crossword puzzle and recipes. (Mia Farrow was the cover in London but not in Madrid; the Princess of Wales is a surefire cover and gets big play in both countries.) All this editing—by fax, by phone, and sometimes by shouting—creates mayhem in the magazines' offices in both capitals, especially in London, where editors are said to be chafing under Don Eduardo's long shadow and are shocked at times by his decisions. He is known to lose his temper and throw things around.

All this editiigby fax, by phone, and sometimes by shoiitingcreates mayhem in Hello!'s offices in Madrid and London.

"He works all the time," Naty says. "They have no social life. It's a family that is always together, always united. The mother, the children. They have no other world.... They have their farm, their cows, their chickens. He likes to hunt and play tennis. They have an enormous farm, with everything—tennis courts, swimming pool. It's fabulous!

"But," she goes on, "they are not known in society and they haven't tried to mix with anyone. Well, maybe that's how the great fortunes are made."

Gaetana Enders, the wife of the former U.S. ambassador to Spain, Thomas Enders, and a longtime correspondent for Hello!, has known the Sanchez family for many years. "It's a very seductive family," she says fondly. "They are very old-fashioned. They safeguard the privacy of the family and trust each other more than anyone else. The family is right-wing and believes in family honor."

Like others who work for Don Eduardo, Enders takes pains to convey her intimacy with the family—she is a guest at the farm, she dines with them and knows their private lives. Speaking glowingly, she assures me, "Eduardo is not impressed by anything... Not by fame, not by parties_He never accepts din-

ner invitations. He hates them. He doesn't give a hoot about glory. This is very unusual in Spain."

It is growing dark in downtown Madrid and soon the tapas bars will be crowded and the galas that may appear in jHola! next week will begin. But Don Eduardo Sanchez Junco won't be attending. He will play a set of tennis and then return home to have dinner and go to sleep. "I have many friends," he says with a shrug, "but I just don't have the time to go out and go to dinners and parties."

In a worn black pullover and opennecked white long-sleeved shirt, his silk socks just short of the cuff of his dark slacks, Don Eduardo hardly fits the image of a man of fortune. Wealth and fame seem to have left him untouched. He is not the type to host a black-tie affair for Placido Domingo or cruise the Aegean on a yacht with Gianni Agnelli.

He easily laughs off the notion of a grand ball featuring the many faces that crowd his magazines to toast the upcoming 50th anniversary of jHola! Perhaps he might agree to give away commemorative designer T-shirts (Valentino has been mentioned), but the idea that really appeals to him is to do "something" involving his readers, to thank them for their loyalty.

His ambitions, though international, are equally modest. "These projects—going to America—fill you with illusions," he says, "but at other times I wonder. I don't have the desire to create other magazines. Our thing is very personal, it's family. I am not drawn to the struggle of turning this into a big enterprise_I would rather watch nature."

Don Eduardo tells me he has a degree in agricultural engineering and in his spare time has turned his land in Burgos into a thriving dairy farm. "I would rather go to my farm and enjoy the landscape, the birds," he says. "I prefer that much more to celebrity."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now