Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowRUDY'S TOUGHEST CASE

In the bare-knuckle contest to become the next mayor of New York City, former tough-guy U.S. attorney Rudy Giuliani is challenging both the incumbent and his own cold-blooded image

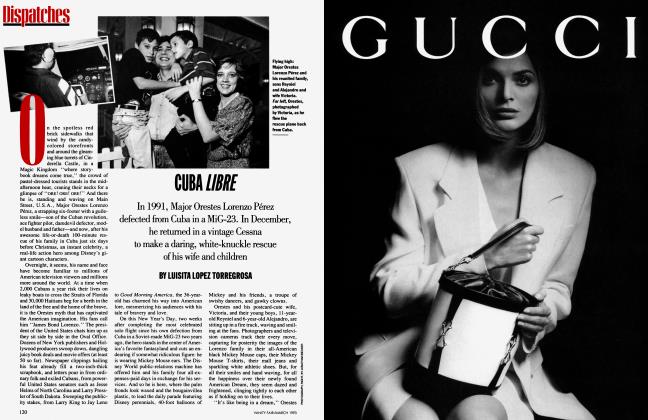

LUISITA LOPEZ TORREGROSA

Politics

David Dinkins always wants the role of victim," Rudolph Giuliani asserts icily. "They say the mayor is a nice man. Well, the pressure is getting to him. He is getting nasty and testy. Look at him on TV. He looks confused, befuddled."

Political campaigns in New York City have never been gentlemanly affairs. Mudslinging and backstabbing are as commonplace as potholes and rude taxi drivers. But the current contest between incumbent David Dinkins, the first black mayor of New York, and Republican-Liberal challenger Rudy Giuliani, one of the most heated mayoral campaigns in recent memory, has a dimension that makes it even more volatile: race.

The campaign finds the city as racially polarized as it was in 1989, when the black career politician and the white former U.S. attorney first went head-to-head. One Dinkins partisan has compared Giuliani to David Duke, the ex-Grand Wizard of the Klan who ran for president in 1992. Giuliani supporters, including many of the Jews and Hispanics who voted for Dinkins last time around, charge Dinkins with favoring blacks. Some of Giuliani's people speak of "the black mob" and anarchy in the streets under the present regime. Black radio stations and newspapers warn of plots in the Giuliani camp to disenfranchise the African-American community, which makes up about 25 percent of the city's population.

Those who know them maintain that neither candidate is personally racist, that neither will stoop to conquer by engaging in "the race race." Yet it lurks under every speech and 30-sec -ond TV spot. Giuliani has fashioned a common-man persona with a centrist agenda for the no-frills 90s: create jobs, return to the basics in education, crack down on crime, lower taxes, trim the bureaucracy. Everywhere he goes he carries a carefully crafted message designed to paint Dinkins as the single-minority mayor. Always to applause, Giuliani promises his audiences that he will be the mayor of all New Yorkers (read: not just of blacks). While blacks are sure to vote overwhelmingly for Dinkins on November 2, and whites for Giuliani, the Hispanic community is up for grabs, but that traditionally Democratic bloc is also the most conservative ethnic community, and Giuliani's message— jbasta ya!—is taking hold.

Inside the Dinkins camp, there is a growing sense of alienation and anger. A prominent commissioner in Dinkins's administration who requests anonymity confides, "If I were an ordinary citizen I would say that it's time for a complete change" at City Hall. Another highly placed city official says that he publicly supports Dinkins and personally likes him but that Dinkins should not be mayor. At a private dinner party, Leland T. Jones, Dinkins's press secretary, blows up when guests pile criticisms on the mayor and predict Giuliani will win. Frustrated, he starts shouting, "Fuck you! Fuck you!"

A Giuliani victory is, however, by no means ensured. While he is out-fund-raising the mayor and finding new converts in the traditional moderate Democratic strongholds, the challenger has to walk a tightrope, balancing his natural aggressiveness with a compassion he finds difficult to display. He is not a beloved personality. "He is loathsome. He's a jerk," says a wealthy matron who lives in Giuliani territory, the Upper East Side. "He wouldn't make it to dogcatcher. . . except look at who he is running against."

Still, the fact that polls show the mayoral race in a dead heat is sweet for Giuliani, who is by definition an underdog in one of the nation's most Democratic big cities—a town where the only Republican mayors in the last 60 years were the charismatic charmers Fiorello La Guardia and John V. Lindsay, who last won as a Republican in 1965. Aware of the odds, Giuliani is coolheaded, cautious, insisting that he has trained himself to tune out the fleeting highs and crashing lows of a campaign. "I've got to campaign every day in exactly the same way," he says flatly, only the reflexive jiggle of his leg hinting at any excitement. "There's no difference in the emotion of it, or the hard work that you have to do."

A victory for Giuliani, 49 years old and virtually untested in the larger political arena, would bring a highly visible national role in a renascent Republican Party and perhaps a shot, in some eight years, at the presidency. At the least, he will find himself playing center field in his field of dreams, at the heart of the city he calls "the center of the universe."

One miserable, muggy evening I am invited to join Giuliani on a private fund-raising tour. Riding along in his dusty gray Dodge Caravan, escorted by a handful of aides and a security sedan, we leave Manhattan at six o'clock. His day started 12 hours earlier, when he awoke in his Upper East Side co-op—a stone's throw from Gracie Mansion, the mayor's residence—and went for his usual three-mile run. ("I used to run around Gracie Mansion," he says with a smile, "but now I'm afraid the security guards might think I'm stalking the mayor, so I run along the East River.")

Despite the tiresome day, he seems fresh and restless, bantering with his aides —the Yankee score and the pennant race are de rigueur—flipping through a copy of the Daily News, catnapping for five minutes at a time, waking up to toss a tennis ball in the air. He loves to tell boyhood stories of idolizing Joe DiMaggio and playing baseball without a glove on broken-concrete lots. He embroiders, of course, scripting a Brooklynite Leave It to Beaver adolescence, although he really grew up in a middle-class neighborhood on Long Island. "See this finger?" he asks. "I broke it once and kept playing. Hurt like hell."

First we get lost in Jamaica Estates in Queens, a pristine neighborhood of $300,000-plus homes and BMWs and Acuras, where a Jewish audience of some 75 people in suits and dresses patiently waits at a private reception. After Giuliani poses for snapshots and signs autographs, the host makes an impassioned speech about Crown Heights, the Brooklyn community where a black child was hit and killed by a car driven by a Hasidic Jew and where, hours later, a Hasidic student was stabbed to death in a racial backlash. The speaker compares the violence against the Hasidim to Kristallnacht in Nazi Germany.

When Giuliani knew the 1989 race was over, he sat with his wife and asked, "Do they really think I'm mean?"

Giuliani sits by, looking grim. He knows he does not have to belabor the point when he finally rises to speak, but he reprises his vow that there has to be equal protection under the law, and that Crown Heights would not have been allowed to happen if "we had a mayor who is awake, alive, and functioning." The line brings down the house.

Four hours and four stops later, Giuliani is seated across from a handful of African-Americans in the dim dining room of Well's Restaurant, a soul-food eatery at Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard and 133rd Street that recalls the jazz era with faded black-and-white pictures of old Harlem scenes. He has taken off his cream-colored suit jacket and rolled up his sleeves and is leaning forward, occasionally sipping a Diet Coke. Giuliani does not smile, sizing up his hosts as they look him over. The leader, a well-known community activist named Evelyn King, is seeking the candidate's commitment to a low-income housing project she is heading. He listens intently, assuring her he wants her support and will look into her problems, but smoothly refuses to make any promises.

It is past 1:30 in the morning when she takes us on a tour of her unfinished three-story project. Giuliani makes a vaguely positive statement and shakes her hand before she climbs into the backseat of a white Saab and drives off. Giuliani's bodyguard looks up and down the street nervously. A strange car approaches slowly and he hustles us back into the van.

Few doubt that Rudolph William Giuliani, a working-class kid bom in Flatbush who became a legend as U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York, might actually cut it as a smart executive and hands-on administrator. But he is bedeviled by a nasty reputation—that he is mean, cold-blooded, callous, temperamental, and vindictive. The image dates back to the mid80s, when he took on the Masters of the Universe, the Milkens and Boeskys and Levines, and in his prosecutorial zeal overstepped the bounds of propriety by having one suspected insider trader handcuffed and dragged out of the Kidder, Peabody investment house— and later had to drop the case for lack of evidence.

The image of an Eliot Ness on the loose, of a self-righteous Reaganite stalking a heavily Democratic city, haunted Giuliani's 1989 campaign for mayor, which he lost by two percentage points— the narrowest margin in a New York mayoral election since 1905. The loss, Giuliani admits, stung badly. On that November Election Day, when he knew the race was over, he sat with his wife, Donna, on the edge of their bed and asked her, "Do they really think I'm mean?"

So here, after almost four years of soul-searching (and a steady grind of seminars and political training), is the new, softer Rudy Giuliani: the all-American guy in a Yankee windbreaker and baseball cap, the coddling dad, the romantic husband, the compassionate politician. "Is it fabricated?" he asks, knowing this is what voters are wondering. "Is it real?"

We are seated, with Donna, in a secluded dining room garnished in loud greens and gaudy blues ("Joey Buttafuoco decor," someone quips) at Tavern on the Green, where Giuliani has just raked in more than $200,000 at a $1,000a-head cocktails-and-handshakes fundraiser. "The fact is I have changed," he tells me, "but probably in the ways that anyone changes over a three-year period. I haven't made any fundamental changes and in fact it is the perception of me that has changed. Not me."

His eyes turn a grayish caramel brown as he speaks. His gaze doesn't stray, and he clutches an empty glass ashtray, leaning forward, his elbows planted on the table. His hair, which is the butt of jokes around town, seems brittle. But the old comb-over has been softened. His face, which four years ago looked puffy, is sharply edged after a loss of 25 pounds in the past year. It looks almost gaunt. "There were parts of me that I wasn't able to communicate to people four years ago,'' he continues. "Part of that was me . . . not really understanding how people perceived me. I assumed that everybody knew that about me: that I care for people, I'm very loyal to people, that personal relationships are more important to me than anything else.

(Continued on page 66)

(Continued from page 60)

"The thing that I find most unusual," he says with a pained expression, "is the weird stereotype of me that I am not able to understand people." Witnesses have cried in his arms, he says. He once rushed to the aid of a suicidal detective. "The notion that the way you operate as a prosecutor is to be harsh on everybody is actually wrong," he insists.

When I ask him to tell me about the most difficult period in his life, he thinks awhile, then says, "After my father died." His father, Harold, who owned a bar-and-grill in Brooklyn and also worked as a salesman, died of cancer in 1981, days before the Senate Judiciary Committee confirmed his son as associate attorney general of the United States. Even now Giuliani seems genuinely troubled by his father's death and speaks of him with awe.

"My father was a very optimistic person, and that lesson was built into my head, maybe into my emotions," he says. "He had a half-empty-half-fullglass approach to life. You focus on your problems for a while, then you work on the half-full part of you. It's also the way you deal with a crisis, and the way you deal with a crisis is to figure out the simple steps that can be taken to first organize things, to get them stable. . . . The way you solve a personal problem is very much the same way you solve a business problem or a governmental problem.

"My father used to take me with him when he went to work, and he also used to sell household items to people and he would take me around with him. My father had a very large extended family, all over the city. . . . [He] was a very social person, loved being with people. My mother would like to stay at home, so he would take me with him."

The attachment lasted through Giuliani's adolescence, which he spent commuting from Long Island to a strict parochial school in Brooklyn. As a chubby teenager and opera buff, Giuliani was a grind, a scholarship student whose disciplinarian parents demanded good grades and clean behavior. He went on to the allmale Manhattan College in the Bronx and New York University Law School, where he dabbled in Democratic Party politics. Although he opposed the Vietnam War and Richard Nixon and supported the civil-rights movement, he was no militant pothead. It never occurred to him to run off with the Woodstock generation. He finally turned to the Republican Party in 1980.

"If I had to sum it up/' Ed Koch says, "you have an incompetent in David Dinkins. In Giuliani you have a wild card."

Plain-vanilla as his life may seem on the surface, Giuliani suffered a failed marriage to a second cousin, a period he declines to discuss. And during his separation from his first wife, he sowed his wild oats, going to discos, dating, and partying. When I ask him about this, he seems embarrassed, and Donna laughs it off, her way of closing the subject.

He is no disciple of "Iron John," no New Age politics-of-meaning yuppie ready to share his feelings. When I prod him to talk further about his grief over his father's death, he protests. "I don't want to exaggerate how upset I was. I wasn't very upset. I was disturbed about the loss of my father, but I didn't have time ..." Donna interrupts to help him out, as she does frequently, explaining that her husband was too busy at that time to dwell on his feelings. He picks up her cue and continues: "When I was in Washington I worked 17 hours a day, and I didn't have time to focus on what was going on in my personal life."

'Rudy is not a natural, he is not a politician," says David Garth, political strategist for Rudolph Giuliani and the man who has guided five of the last seven winning mayoral campaigns in New York City. Garth is wearing a lavender polo shirt under a khaki safari vest, a rumpled gnome in a plush Park Avenue office. His studied gruff demeanor and reputation as a hothead are designed to intimidate the press, and everyone else. But Garth was a natural for Giuliani, who badly needed a political sage and media manipulator to sell his candidacy. The Garth Group receives $25,000 a month from Giuliani plus about 15 percent of the money the campaign spends on TV advertising.

Leaning forward on his massive wooden desk, Garth pinpoints Giuliani's strengths and weaknesses. "The fact that he is not a politician may be one of his strongest assets. On the other hand, it can get him into trouble. But he happens to be very, very smart and a very quick learner. I think Rudy is a street kid too. There's an interesting parallel to me between [ex-mayor] Ed Koch, [New York governor] Mario Cuomo—Mario would die— and Rudy. They all come from . . . 'working-class' is the nicest way I can put it. Koch came from a cold-water flat; Mario's father had a small bodega; Rudy did not come from any kind of wealth. There is a kind of New York grittiness and toughness about them."

It is the tough-guy temperament that gets Giuliani into trouble. Friends and foes point at two episodes seared into the memory of New Yorkers. One is his conduct last year when off-duty policemen stormed the steps of City Hall, in part to protest Mayor Dinkins's creation of an all-civilian review board. Some of the policemen, who had been drinking beer, were carrying a sign saying, DUMP THE WASHROOM ATTENDANT. Giuliani says that when he arrived at the site, in the company of members of the Hispanic policemen's association, he was not aware of the racial posters. Checking out the wild scene at City Hall, he led some of the policemen to the official rallying site a block away. He tells me he shouted "bullshit!" twice to mock Dinkins, who had used that expletive a few weeks earlier in response to a complaining policeman. But Giuliani's "bullshit" and the anger that showed on his face were caught on videotape and played repeatedly, making him look like an instigator whipping up the storm troopers.

The other vignette that haunts him took place on Election Night in 1989, when his supporters booed Dinkins while Giuliani made his concession speech. Afraid that the media would depict his backers as racists jeering the first black mayor of New York, Giuliani says he tried to quiet them down. When that did not work, he shouted into the microphone, "Shut up! Shut up!'' Whatever his intentions, the image that came across was of a man out of control.

"He was not exactly a statesman [at the police rally]," says former mayor Edward I. Koch in a rare understatement. Koch, who now seems more popular with the voters in New York than when he lost his office in 1989, may well play the role of kingmaker in this election. He still bears a grudge toward Giuliani about the last election—"He was rather mean to me when I ran in '89"—but he has more serious problems with Dinkins. "If I had to sum it up," Koch says, "you have an incompetent in David Dinkins. In Giuliani you have a wild card. I believe Giuliani is more competent than David Dinkins. I don't know that he is as nice."

In the past two years, Giuliani has taken Koch out to lunch three times, thanks in part to the maneuvers of David Garth, who ran all four of Koch's campaigns. "Giuliani's a charmer," Koch concedes, "and he's got to show that part of him. Everybody has a private persona and a public persona. Rudy's public personality is that of the killer."

Robert Shram, a Washington-based media strategist who has worked for Dinkins on two campaigns, calls Giuliani a "humorless Koch" who is temperamentally unsuited to the task of being mayor, a theme that Dinkins echoes in his appearances and TV commercials. "Watch him inciting the police," Shram says ominously.

Jackie Mason, the comedian who supported Giuliani in 1989 but was cut loose from the campaign after he called Dinkins ' ' a fancy shvartze with a mustache, ' ' says Giuliani is a "selfish opportunist" who betrayed him over a harmless joke. Telling me that he wants a public apology from Giuliani, Mason says, "Somehow it must be that deep in his heart he is so ambitious that all of a sudden whatever compassion or decency he really has, all of a sudden, gets lost. I don't need a man like him destroying my reputation because he needs an example to prove he's a humanitarian. If that's the only way he could do it, he doesn't deserve to be a mayor. He deserves to be the boss of a concentration camp in Germany."

Others who are less partisan and personally embittered agree that Giuliani can be unpredictable. A veteran New York journalist who knows Giuliani and likes him warns that "Rudy is careful, but he does have this volcano simmering that can erupt anytime."

If Giuliani is keeping himself in check, members of his staff sometimes do not. Under the tutelage of Garth, who will upbraid any reporter he deems unfair, Giuliani's press aides see themselves as besieged by most of the New York media. "You've got a tough press here which makes the rest of the press in the country look like the daisy chain at Vassar," says Garth.

The political guru handpicked Giuliani's director of communications, Richard Bryers, a high-strung, pony tailed 37year-old. On a day when The New York Times carried a front-page article favorable to Dinkins, Bryers laced into a veteran Times correspondent. "I am not going to talk to The New York Times today," he shouted into the reporter's face. Then he walked away.

"Everybody has a private persona and a public persona. Rudy's public personality is that of the killer."

The Times is Giuliani's nemesis, and he makes no bones about it. "They are always dragging out that I am Catholic," he complains. "That story on education, for instance. They had to stretch to put in that my children go to Catholic school. And that's wrong anyway. My daughter is in a nursery." At another point, a Giuliani aide objects to a Times article describing Giuliani as having "hunched shoulders." But what most rankles Giuliani is the poor play his policy speeches receive. He points out that a routine political endorsement of Dinkins garnered more attention in the Times than Giuliani's recent address on quality-oflife issues—crime, garbage collection, parking fines, panhandlers.

The feud with the Times reached such a tense state that intermediaries stepped in to patch up relations. But that battle is a playground scrap compared with Giuliani's war with New York 1, the all-news cable station owned by Time Warner and overseen by Dinkins supporter Dick Aurelio. Day after day Giuliani goes head-to-head with NYl's cameras, berating the station to its face for what he considers its role as a Dinkins campaign vehicle. One afternoon on a sidewalk in lower Manhattan, where Giuliani received the endorsement of several police fraternal organizations, Richard Bryers blasts a NY 1 reporter. "We're not going to give them our press schedules anymore!" he yells. "If they can't be straight, we're not going to help them."

The media wars are not confined to the Giuliani camp on Madison Avenue. Across town, at Dinkins's campaign headquarters on West 42nd Street, Bill Lynch, another legendary strategist with a difficult temper, scores the New York press for failing to publicize the mayor's successes and for attacking his handling of the Crown Heights crisis. "In 1991, the mayor was given accolades for what he did in Crown Heights by the same media that now criticizes him," he says. "I find that very, very confusing. If I seem hyper about this when reporters talk to me, I have to ask myself, Did I live in a different world at that time?"

A longtime Dinkins protege and the mayor's closest adviser, Lynch seems weary, and admits he is in a "funk," but not about the mayor's campaign, which he predicts will take off like a rocket in the final weeks, when the big guns of the Democratic Party will be trooping to the city to give the mayor a boost. "I look at us being a little bit behind or running dead even, and I would argue that we have not surfaced our campaign yet."

Other leaders within the black community seem less optimistic. Over lunch at the Pierre hotel, the Reverend A1 Sharpton picks apart the campaign, saying, ''Dinkins hasn't developed a realistic strategy. He's a gracious man, but [in the last election] people voted for a lot of reasons other than David Dinkins. I think the Dinkins staff has an unrealistic underestimation of Giuliani." In the black community, Sharpton says, ''there's not the level of enthusiasm for Dinkins that I would expect."

But Lynch, who ran Dinkins's 1989 campaign, believes that, despite the negative publicity, his side has the edge. "We can put an army in the street," he boasts. "I don't think Mr. Giuliani can put all the organized volunteers we can put out there to pull out our vote. I think that's the difference.

"Where I think we have to be careful is that there are no natural disasters," he says ominously. This makes him think to add, ' 'Mr. Giuliani said recently that he is one riot away from being mayor." In the tinderbox racial climate of New York, this is an incendiary statement. I ask when Giuliani said this. "He's quoted as saying"—Lynch shouts into my tape recorder—" 'ONE RIOT AWAY FROM BEING MAYOR,' MR. GIULIANI!"

Stunned, I ask for some verification. "We'll get you the text," Lynch offers, and picks up the phone to call an aide. While we wait, I ask him why the mayor did not fire a deputy campaign manager, former boxing champion Jose Torres, who compared Giuliani to David Duke. He laughs and corrects me: "Now, that's my remark. I said it a year ago on a radio-station talk show right after the police riot that he was involved in." Lynch reminds me that Torres made a slightly different comment. "What he said was that Giuliani draws the worst elements, like [the K.K.K.], to his campaign." The mayor, responding to the outcry from the Giuliani camp, reprimanded Torres but did not fire him. The incident became a cause celebre, partly because Giuliani had repudiated Jackie Mason for making his "shvartze" joke. When I mention this to Lynch, he dismisses the comparison, saying the two cases are not the same.

An aide enters and Lynch asks him, "What day did Rudy say, 'I am one riot away from being mayor'?"

"August," answers the aide. "Roy Innis."

Innis, a fringe black conservative defeated by Dinkins in the Democratic primary, is difficult to confuse with Rudolph Giuliani. "I'm sorry. I got it wrong," Lynch says matter-of-factly.

I make the point that unsubstantiated and untrue information is being bandied about by both campaigns. He immediately takes offense. "Hold it! Five minutes ago you said Jose Torres said something and I corrected you. ... I learned about this [the riot quote] 45 minutes ago. I thought I heard 'Giuliani' and then I went and got the person who had the information and brought it here to you. I didn't go out publicly with it first. ... I would expect you to check everything I said. Most print reporters don't do that."

"Where I think we have to be careful is that there are no natural disasters/' says Dinkins's closest adviser ominously.

(In fact, in checking what Lynch said, I found that Roy Innis had indeed made the statement in August—of 1991. It is odd that Lynch, who was deputy mayor at that time, had not heard the quote until 45 minutes before our interview, and odder still that he understood it to be said by Giuliani.)

Turning back to the campaign, I ask Lynch what other plans he might have for the mayor. "Make him over," he replies sarcastically. "Get him a new pair of glasses. Haircut. New suits. That's what David Garth did with Giuliani." To drive home the point that Giuliani is Garth's puppet, Lynch says of Dinkins, "He's no windup toy that you can put out there and get him to do anything his handlers tell him to do."

The impression that Rudy Giuliani is a cardboard character manufactured by clever image engineers enrages no one more than his wife, who sees him as a dashing dreamboat with a caring heart. "I feel very blessed," 43-yearold Donna Kofnovec Hanover Giuliani says in her crisp, straightforward style. "Not everyone meets the love of their life, and we did."

It is a storybook romance, Donna and Rudy meeting in midlife on a blind date in Miami Beach at Joe's Stone Crab, the famed seafood house. It was 1982 and Donna was already divorced (Hanover was her husband's name) after a nineyear marriage that she will not discuss. Rudy was separating from his wife. It was, they say, love at first sight. "I saw him," she remembers, her eyes glistening, "the way he set his shoulders, and I knew he was a man that could take care of himself and could take care of me."

She was an anchor at a Miami TV station. He was the associate attorney general at the Justice Department in Washington. Later, she barraged him with questions because she was attracted to him and wanted to know if they thought alike. He was prochoice, she found out to her relief. He was not a rightwinger, but a moderate, an independent thinker. He proposed, by telephone, six weeks after their first meeting. "I was surprised," she says. She didn't want to leave her job in Miami, so he offered to give up his job at the Justice Department and move down to Florida. "I knew that ultimately he would want to practice very high-powered law," she says, "and New York is the center of the world." Pleased that he had offered to give up his D.C. career for her, she elected to move to Washington instead. A year later, he accepted the job of U.S. attorney in New York, where she became an anchor at Channel 11. (She is now a part-time journalism professor at N.Y.U.)

With two children, 7-year-old Andrew, a first-grader at an elite private school, and 4-year-old Caroline, who attends a private nondenominational nursery, the Giulianis project the picture of a perfectly adjusted family, a solid marriage and partnership. Asked what binds them, Donna says, "He is witty. We never lack for something to talk about. I just find him the most fascinating man I ever met." She giggles. "And he's romantic. He likes to go shopping by himself and buy clothes for me," she confides. "He always likes things a little funkier, a little more avant-garde, than I ever look at myself. I am sort of a fairly conservative dresser. I usually wear jackets, black skirts—you know, kind of uniforms so when you get up at five o'clock in the morning you don't have to think about it. He'll find dresses, maybe things that could be accessorized a bit more. He does get embarrassed when I tell him there's something at Victoria's Secret that I like."

Donna Giuliani doesn't explain her husband's policy but his personality. One day I ask her why he loses his temper, why he seemed to incite the policemen, why he shouted at his supporters. ''You know, everyone misunderstands those things," she says. "You have to understand that his role models were not politicians or statesmen. They were baseball coaches and football coaches, like Bill Parcells. And that is a style of leadership that's different. Coaches yell to get the players going. They aren't quiet. So on Election Night, Rudy was just trying to get his supporters to stop booing Dinkins. He couldn't get them to quiet down. So he shouted at them. " She feels the police incident was misrepresented by the media. "Rudy was not aware how he came across. He came home, in fact, and told me it had been wonderful. ... He had been told so often that he was unemotional that all he was trying to do was show emotion, and he was on a stage and trying to reach a big crowd. On television, with the close-ups, it looks different."

But, yes, she says, Rudy loses his temper and they have occasional fights, "the usual fights married people have. He gets mad because I won't throw out the newspapers and he likes everything tidy. I get mad if he doesn't consult me before doing something. Nothing big, but, yeah, we fight."

Their home, a $250,000 two-bedroom apartment in a postwar beige brick high-rise, "looks like it was decorated by Toys 'R' Us," she says. "It's not Park Avenue or Fifth Avenue. Believe me, there's no decorator involved. The house is generally a mess. We live a very New York-style life; we eat out, we get takeout. But I can cook. I make the best French toast you ever tasted in your life."

On a recent morning Rudy Giuliani comes down from his apartment to have one last long talk with me. We are meeting at the Mansion diner, one of his hangouts, with the clatter of breakfast dishes in the background. As is his wont, he wastes no time in taking a few shots at Dinkins, but by now I have heard most of it, so I ask him to tell me why he loves The Godfather. He laughs and says he has read the book 3 times and seen the movie 8 or 10 times. But that's nothing, he says, compared with his friends, who have memorized all the dialogue. Which character does he identify with? He pauses, startled at the question, and finally says, "Well, none. But I imitate Brando."

And he mimics Brando's croaky voice: "It's nice of all of youse to come here from as far away as California and some of you from as far away as New Orleans." Grinning mischievously, he recalls doing his impersonation in front of Mario Cuomo at a broadcasters' convention in the Catskills back in 1988. "At first, he looked a little annoyed. He didn't crack up. He was like this [Giuliani makes a dour face]. He wouldn't look at me. I think he thought I was thinking of him. Then all of a sudden the place started laughing. He started laughing. I could see him relax. And I said, 'Mario, just kidding, just kidding.' "

Grinning mischievously, Giuliani recalls doing his impersonation of Marion Brando in The Godfather in front of Mario Cuomo.

But how could an Italian-American former prosecutor admire The Godfather? Suddenly he becomes very serious and looks straight at me. "I think the Godfather movie has taught a lot to Italian-Americans, even those who say it's bad for the image of Italian-Americans—which it is, no question. It demonstrates what Italian family life is like. Big Sunday dinners, which I have fond recollections of, going to my grandmother's house, having these big dinners. These gigantic weddings, in which some of the family is feuding with some other part of the family, and Uncle This won't talk to Uncle That. Put the Mafia part aside. The horrible part. The Italian-American family in which all the people in the family were plumbers and electricians and schoolteachers and whatever else—the family part would be very much the same as you see in The Godfather.

"The reason I got involved investigating and prosecuting organized crime," he continues, "was that it just happened to be the biggest problem. It was like six months into those investigations that I realized the connection that would be made between my being Italian-American and organized crime. It wasn't something I really thought about. And then some Italian-Americans wrote to me saying that I was being unfair, or that I was a self-hating Italian. I don't understand why they have that resentment. I thought I played a helpful role, in that I am Italian-American, to show how prejudiced many people are in identifying all ItalianAmericans with that class of people."

Most of Giuliani's life, it seems, has been a struggle against that image. As a white-shoe law-firm partner, as persecutor of the Mafia and corrupt politicians, and as a candidate with the starched-shirt style of a Wall Street banker, he has kept himself firmly buttoned up, defying the stereotype of bombastic Italian macho. He is so sensitive to the image of the explosive Italian that he bristles when he hears he is temperamental—"It's an ethnic slur," he tells me—yet he is caught between the world he was born into and the world in which he now finds himself. It may be this battle to keep himself under control that makes him stiff-necked and aloof in public.

I think back to an old-fashioned Italian feast Giuliani attended in Astoria, Queens, one of the dozens of ethnic celebrations that are routine for every mayoral campaign. Catholic processions, bouncy Italian music, carnival games, the aroma of grilled hot sausage and peppers. Giuliani walked through the crowd, blessed by wrinkled old women in veils, hailed by muscled young guys and flashy girls who yelled, "Rudy! Rudy!" He gave the thumbs-up, he hugged men and rubbed the heads of little kids. He paused for the obligatory bite of calzone, which he insisted on paying for himself.

Finally, he mounted a makeshift stage hung with Italian flags and blue-andwhite Giuliani posters. He was introduced in Italian—"// prossimo sindaco di New York, Rudy GiulianiV' — and the sweating crowd roared. He stepped up to the microphone and swung into his rah-rah speech. But this time he was loose, totally relaxed. Every line was a hit. At that moment he wasn't a candidate wooing a crowd, he was Joe DiMaggio in gray pinstripes, the hometown hero at home.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now