Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIT ALL BEGAN AT PARAMOUNT

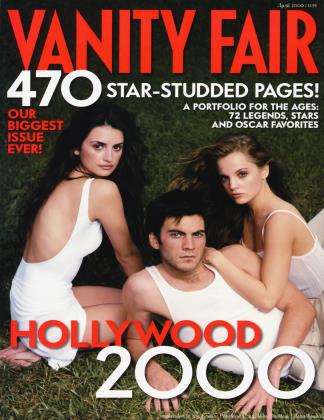

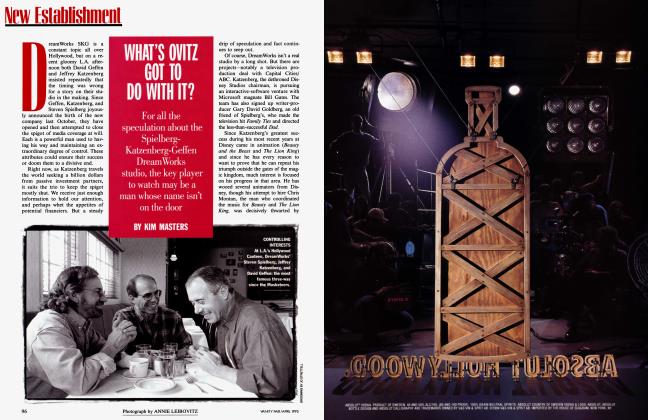

THE EXECUTIVE SUITE

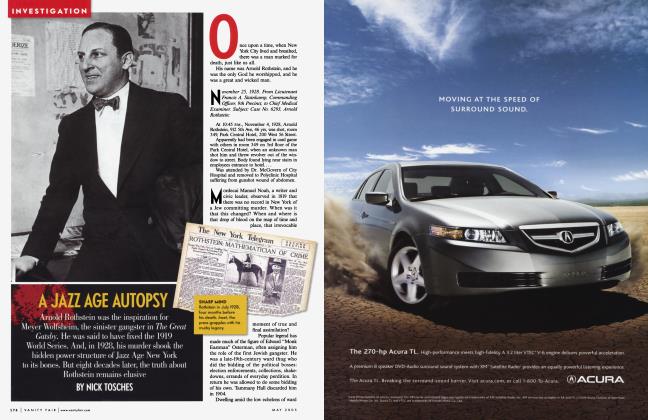

As the 80s started, Paramount's all-star management team included Barry Diller, Michael Eisner, and Jeffrey Katzenberg. In her new book, The Keys to the Kingdom, the author unravels their tense, mistrustful dance of power, which ended only with the arrival of Martin Davis-a man they feared even more than one another

KIM MASTERS

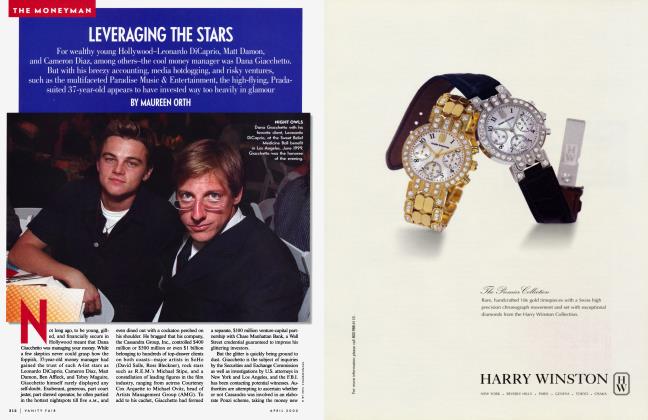

Michael Eisner has enjoyed a stunningly successful career in the entertainment industry: his role in reviving the slumbering Walt Disney Co. has become the stuff of business legend. But before he got to Disney, Eisner was part of another famous, equally volatile dynasty. From the mid1970s through 1984, Paramount Pictures was the home of a cadre of executives known as the Killer Dillers—a group of "baby moguls" assembled by Barry Diller, who had shocked Hollywood by becoming chairman of the studio in 1974 at 32. The Killer Dillers included not only Eisner but future Disney studio chairman Jeffrey Katzenberg, future producer Don Simpson, and

Dawn Steel, who became the first woman to head a major studio.

Diller and Eisner had a tempestuous relationship which produced such hits as Raiders of the Lost Ark, Terms of Endearment, and Flashdance. Katzenberg served as Eisner's eager lieutenant—and later seemed to mimic many of his techniques in seeking to expand his own power when the two moved over to Disney. But in the end Katzenberg's attempt to build his empire at Disney would fail, just as Eisner's did at Paramount. Each man would find that an intense and emotional relationship with a demanding boss ultimately led to rupture. This is how it all began.

If John Lindsay had been presidential material, one can only imagine how life might have played out for Jeffrey Katzenberg, who, at the tender age of 14, had started as a volunteer for the New York mayor in 1965. Over the next several years, Katzenberg became a trusted gofer, so much so that a special prosecutor subsequently put Katzenberg—who developed a reputation as a Lindsay "bagman"—under investigation. (The prosecutor found no impropri-

Excerpted from The Keys to the Kingdom: How Michael Eisner Lost His Grip, by Kim Masters, to be published this month by William Morrow; © 2000 by the author.

eties.) At 21, Katzenberg was an advance man for Lindsay's 1972 campaign for the White House.

But Lindsay's bid failed. Two of his top former aides opened Jimmy's, a hot Manhattan restaurant which provided entertainment from singer Betty Buckley, saxophone player Stan Getz, and a rising comic named Don Imus, among others. Katzenberg worked at everything, functioning as a savvy maitre d' or washing glasses behind the bar. Meanwhile, his friends from the Lindsay administration pushed him to attend college at night. Katzenberg tried it at New Y>rk University, but didn't stay long. His friends enlisted the help of two brothers who were suppliers to Zales Jewelry— and avid gamblers. They ran a casino on the Caribbean island of St. Martin, where Katzenberg was sent to study the business from the ground up. "I suggested he'd make a good croupier," says one of Katzenberg's mentors, Lindsay-administration official Richard Aurelio.

Katzenberg also spent hours practicing counting cards at blackjack. He was tutored by an associate of the brothers' who was alleged to have a gift for fixing college basketball games. With $10,000 from the brothers in his pocket, Katzenberg set out for Freeport, in the Bahamas The brothers agreed to split Katzen berg's winnings with him. "For wiseguys, what was quite wonderful about them is they said they would stake me for six months or for $250,000, whichever came first," Katzenberg says. "They allowed me the fantasy and dream of doing this insanely bizarre thing."

Naturally, Katzenberg was obsessed with making his $250,000 goal. He went from casino to casino, finally making his way to Vegas with about $200,000. He was closing in. But the house got wise to him, roped off his table, and started cutting the deck higher to make it more difficult to count the cards. Katzenberg began losing and eventually his money was gone.

The casino planned to put Katzenberg's picture in a book of card counters and other unwelcome types. The brothers intervened on his behalf. Katzenberg agreed to quit gambling in order to keep his photo out of the book.

By 1974, Katzenberg's mentors had helped him find work as a $125-a-week assistant to producer David Picker, who was then in the midst of making Lenny, the Bob Fosse film based on Julian Barry's play about comedian Lenny Bruce. Katzenberg, then 23, was enjoying himself immensely—accompanying Dustin Hoffman (who played Lenny Bruce) to Miami and flitting about in limousines,

yachts, and jets—when one day Picker said, "Do you know who Barry Diller is? He's a great guy, very smart, and looking for an assistant."

The son of a well-to-do real-estate developer, Diller had attended Beverly Hills High and briefly enrolled at U.C.L.A., but didn't graduate. Instead, he pestered Danny Thomas, whose children were his schoolmates, to get him a job in the William Morris mailroom. Once there, he soaked up everything he could learn from the agency's files. Within a few years his friend Mario Thomas introduced him to Leonard Goldberg, then head of programming at ABC, who hired Diller as his assistant. Displaying a lethal efficiency, Diller quickly climbed the ladder at the network. He played a key role in developing the "Movie of the Week" franchise as well as TV mini-series such as Rich Man, Poor Man. In 1974, legendary Gulf & Western chairman Charlie Bluhdorn shocked Hollywood by naming Diller—

Katzenberg was the most efficient young man I had ever seen—other than Barry Diller."

who was just 32, and whose experience was exclusively in television—to run Paramount Pictures.

Katzenberg wasn't especially eager to leave his job. But the day after he had a somewhat testy interview, Picker called to say that Diller was offering him the position. "I think he saw a lot of himself in you," Picker said.

On his first day, Katzenberg sat at his desk at the Gulf & Western offices in New York when suddenly he heard the harsh buzzing of Diller's intercom. When he went to the boss's office, Diller pushed a thick stack of papers across the desk and said, "Tell me what you think."

This was the manuscript of the Judith Rossner novel Looking for Mr. Goodbar. Katzenberg labored through it and returned to Diller. "I have no idea how you make this into a movie," Katzenberg said. "It was all told from inside her mind."

"That's not your job," Diller responded. "That's what a filmmaker will do. Do you think it's a good story to make into a movie?"

Katzenberg tried again. "I imagine women will be really interested," he said.

"How would you know?" Diller snapped. "You're not a woman, are you?"

Katzenberg looked down at his crotch, then back at Diller. "Not that I know of."

"Your job is to go out and find ideas that interest you, that you love—not like— that you love sufficiently to put your career on the line, to have a level of passion to want to make something and to have the courage of your convictions. There is no way you will ever know what a housewife in Kansas or a businessman in Chicago wants to see. Your job is to find things that interest you.... Then what you do is you say, 'Yes.' You close your eyes, cross your fingers, and pray that there are millions of other people who feel the same way you do. Anytime you presume what someone else will like, you will lose."

Katzenberg tells many tales of his youthful cockiness, but he craved the approval of his bosses and worked tirelessly to get it. As Diller's assistant, he had special responsibility for decorating and overseeing Gulf & Western's guesthouse on the company's extensive property in the Dominican Republic. Company chairman Charlie Bluhdorn was especially pleased with the results. "Jeffrey's job, when I met him, was to \ outfit that house with the powerboat and water skis and floats for the pool," remembers one prominent producer. "He was into it."

When Diller invited Bluhdorn to Los Angeles, Katzenberg's job was to remain glued to his side, ensuring that he had nothing but fun. And when Diller wanted to throw a last-minute 30th-birthday celebration in New York for his friend Diane Von Furstenberg, Katzenberg organized a party at a popular Chinese restaurant at Third Avenue and 64th Street; guests included Mick Jagger and Henry Kissinger. (Diller marked the occasion by presenting Von Furstenberg with 30 diamonds in a Band-Aid box; Katzenberg had been responsible for getting the diamonds.)

From the start, Katzenberg never did his job by half-measures. Martin Starger, who had been Diller's boss at ABC, remembers that Diller invited him to use the Dominican Republic house for a vacation and promised to have his assistant make the arrangements. Minutes later, Katzenberg was on the phone from New York, asking about Starger's flight plans. When Starger arrived at the airport to make his connection, he was greeted by Katzenberg, who was wearing a dark suit even though it was a Sunday afternoon.

"He takes me from one plane to another," Starger recalls. "I said, 'You came all the way from Manhattan to make sure I get from one plane to another?' He asked

what I like to drink, all that stuff. I get there and walk into the house and the phone rings—I swear not two minutes after I walk into the house—and I hear, 'Mr. Katzenberg on the line.' It was unbelievable. I mean, the guy knew what room I was going into from 3,000 miles away. 'I understand you went skeet shooting. Did you enjoy it?' He was the most efficient young man I had ever seen—other than Barry."

But perhaps because Katzenberg was such a clever assistant, it wasn't long before Diller concluded that the arrangement wasn't working. "He had alienated a lot of people in the first six months or so, which is what happens when you're an assistant and you're young,"

"Barry was king. Michael brought this incredible flashing energy, and Barry would take from that

Diller says. "I couldn't have him be my assistant anymore, because it wasn't healthy." In 1977, Diller decided to reassign his protege. "I thought enough of him to get him a real job," he continues. "I threw him into the marketing department to get his bearings, and he didn't disappoint me."

Katzenberg didn't dally in the marketing department. While there, he met the 34-year-old Michael Eisner, the new head of the studio. Diller and Eisner had worked together at ABC—first in New York and then in Los Angeles— and they had clashed often. While Diller was from a well-off family, Eisner came from even more serious wealth. His greatgrandfather Sigmund had emigrated from Bohemia and established a uniform business that supplied the U.S. Army and the Boy Scouts. His mother's family had a 74acre estate in Bedford Hills, north of Manhattan, with more than 15 employees. While Eisner did not live up to his parents' hope that he would attend Princeton, he received a degree from Denison University in Ohio. When he landed a job

at ABC, it was inevitable that he and Diller would square off. Their former boss Martin Starger remembers, "Each knew what the other made and what the other's office size was."

The two men had very different styles: Diller was more confrontational and direct. "Michael was hard in a much different way," remembers executive Dick Zimbert, who worked for Diller at ABC and Paramount. "He had more warmth. . . . Barry made it really hard. Michael made it fun." Still, Zimbert says, Eisner was as effective as Diller at getting his way. "Michael was not a beater-upper—he was a manipulator," Zimbert says. While Diller left bruises, Eisner tried not to leave any fingerprints.

While Eisner had not been displeased when Diller finally left ABC to run Paramount, he began to chafe while working for legendary network execk utive Fred Silverman. In 1976, he accepted Diller's offer to become president of the studio, which was faring so poorly L that Diller had actually offered to resign his post as chairman. Even before Eisner had warmed his chair, however, the studio started releasing a string of hits that would include Saturday Night Fever and Grease.

From the start, Katzenberg was charmed by Eisner's energy and self-deprecating humor. He also liked a rising young production executive named Don Simpson, then 30—who happened to be a favorite of Eisner's. Though the straitlaced Katzenberg seemed to have little in common with the hard-partying, profane Simpson, this would scarcely be the first time that Katzenberg had enjoyed a friendship with someone who may not have adhered to all laws—and between hookers and drugs, Simpson broke his share.

Katzenberg was promoted to production in 1977. But his first assignment there was almost a career ender. He was asked to oversee a low-budget feature-film version of the Star Trek television series, starring William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy. He didn't have a clue what he was doing, but Eisner seemed to have confidence in him. "He would believe in somebody," Katzenberg says. "If you were a talented carpenter, he would think you could be a brain surgeon."

Thanks to script problems and the studio's lack of experience with special effects, Star Trek turned out to be a nightmarish production, with a budget that soared to more than $40 million. Worse, the project seemed deadly dull—a sure bomb. But to everyone's surprise, audiences jammed the theaters, making the

picture an $82 million hit. Katzenberg, whom Diller describes as "the little bird dog on the movie," had survived and even triumphed. Star Trek, with its many sequels and television spin-offs, became Paramount's biggest franchise—a property ultimately worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Bluhdorn urged a run at a Star Trek sequel, and producer Harve Bennett began developing a script, which went through many drafts. At one point, Eisner and Katzenberg summoned Bennett to Paramount. "This is going to be a great movie," Eisner told him before launching into his critique of the script. Within a couple of minutes, Bennett says, he realized that

"Any meeting that Barry and Michael were in, you could sell tickets to. It was unbelievable how they would scream."

Eisner was reading from an earlier draft.

"This is the wrong script," Bennett said. "I agree with you, but all these changes have been made."

"Who gave me this script?" Eisner asked, looking pointedly at Katzenberg. "I was up from 12 to 1 reading this script."

"I don't know what to tell you," Bennett said.

"If I spent an hour of my time reading this script, I'm going to give you my notes," Eisner continued. Bennett realized that Eisner was determined to go ahead, and

for the next 45 minutes listened to notes on a script that had already been revised.

By 1980, Paramount had established the disparate but exceptional executive team that would become legendary. Diller was as sleek as ever in handmade white cotton shirts and impeccable suits in varying shades of beige. The perennially rumpled Eisner was in corduroys or dark suits that were best described as "loosely tailored." Katzenberg was preppy in Lacoste shirts and slacks. "No matter what the chemistry was, those were incredible years to be making movies or television at that studio," says Harve Bennett. "Within the chaos, there

was order. Barry was king. Michael brought this incredible flashing energy, and Barry would take from that."

The executives who worked for these two men lived with a sense of exhilaration combined with dread. "We were all intimidated by the collective power of Michael Eisner and Bar~*.Jer," Paramount executive Dawn Steel later remembered. "We would see them in the commissary or the parking lot and we'd be panting like dogs, like 'Oh, please just recognize me.'"

Katzenberg rose quickly. His responsibilities expanded to acquiring films to put into Paramount's distribution pipeline. In April 1979 he championed Meatballs, a low-budget picture starring Bill Murray. The picture, which had cost about $1.5 million, was a sleeper hit which grossed $43 million—at the time the most profitable "pickup" ever.

From the start, the Diller regime tried

to keep things cheap. The studio's game was "to break the agents' hold on Hollywood," as Steel later said. Diller and Eisner didn't want to take packages of scripts, actors, and directors from agencies such as Mike Ovitz's up-and-coming Creative Artists Agency. Cheapness came naturally to Eisner. "It becomes almost a challenge for me not to pay the ridiculous prices that get paid in this town," he said at the time. Eisner was often accused of stifling creativity, but those who offered such criticism simply failed to appreciate what he was about. To Eisner, the film business was a business. It wasn't about making Reds, Warren Beatty's 1981 epic about left-leaning journalist John Reed—that was Barry Diller's province.

With their contrasting styles, Diller and Eisner fought like animals. But their differences proved complementary. "Any meeting that Barry and Michael were in, you could sell tickets to," recalls Rich Frank, former television chief at Paramount. "It was unbelievable how they would scream and yell and fight with each other. And they could walk away and there was no residual negativity from the meeting." One low-level staffer, who went on to become an extremely successful producer, used to watch from his window on Friday afternoons as the two emerged from the Paramount administration building and invariably started to quarrel. He was so mesmerized by the angry, sweaty gesticulations that he brought a long-lens camera to the office to photograph the spectacle. (He kept the pictures for his private collection.)

"All the arguments are the same to me," remembers Dick Zimbert, an executive who witnessed many. "One of the major difficulties in a studio is the timing problem. You've got to get hundreds of pieces together at one time to start the camera rolling. And Barry, with this convince-me attitude, would make Michael crazy. Michael would sweat with an enormous effort to pull these pieces together. And Barry would start: 'Why does that writer get credit? Why does he get gross after breakeven?' Legitimate business questions, but tension would rise and they would yell."

Once, junior executives David Kirkpatrick and Ricardo Mestres were going to accompany Eisner and Simpson to New York to make a presentation to Bluhdorn about the studio's activities. Both were

excited because this was to be their first big meeting in Bluhdorn's presence. They meticulously organized their materials. But in a meeting that dragged on for more than four hours, their part of the agenda was never discussed. Instead, Diller and Eisner—with Simpson pitching inshrieked at each other about whether Olivia Newton-John should do a cameo in a planned sequel to Grease. Bluhdorn appeared briefly in the middle of the meeting and came up with one of his many unlikely movie ideas. "I think I would like that boy from Stripes and that girl from Private Benjamin to do a movie together," he said. With that, he left. (The Bill MurrayGoldie Hawn pairing never happened.)

Diller claims that his fights with Eisner were simply part of the studio's modus operandi. "It was Michael and me, me and everyone," he says. "We had a system of advocacy which produced endless argument, almost every day."

In one sense, Diller and Eisner were in complete agreement. Both wanted hits, which meant making profitable mass entertainment. Diller still had an appetite for highbrow fare such as Reds, while Eisner's tastes were generally more commercial. But as time went on, studios increasingly favored the safe formula over the gamble. "Reds was the end of something," says Warren Beatty. ^ "Whatever Paramount was, it was a pretty goddamned good training ground for what the movies became. It became about mass release, which changed the content. Everybody has been on that train ever since. But I don't know if that train has done a lot for movies."

Despite its internal friction, Paramount's golden team churned out impressive hits during the early 1980s: Airplane!, Ordinary People, The Elephant Man, Reds, and Raiders of the Lost Ark, which was championed by Eisner. But the studio also had some notorious losers, such as Popeye and Ragtime. Other pictures died with less fanfare. Mommie Dearest, starring Faye Dunaway as Joan Crawford, lost more than $4 million; Partners, a Ryan O'Neal vehicle about an undercover cop pretending to be gay, lost $6 million.

Eisner was frustrated, says an executive who worked for him, because it seemed to him that Diller had tried—not very successfully—to cut him out of the loop to Bluhdorn. Diller denies this. "I was never insecure about my relationship with Bluhdorn," Diller says. "Almost without exception, I was very happy for Michael Eisner and Charlie Bluhdorn to talk. And Michael was very careful. Once, Bluhdorn tried—unsuccessfully—to get Michael to overrule something I had said.

It was very painful because I was on a holiday and I had to spend 10 hours or so fixing it."

One day in 1981, Eisner summoned Ricardo Mestres and David Kirkpatrick to his office and asked them to tape him as he gave a stream-of-consciousness analysis of the film business—what kind of movies to make, what kind of directors to hire. (The subtext, says an insider, was Eisner's attempt to persuade the board to give him control of the studio's marketing division, which was then run by Frank Mancuso.) A January 1982 draft reads, "Decisions are often made for the wrong reasons when things are going well. Success tends to make you forget what made you successful. Just when you least suspect it, the fatal turnover shifts the game, and the other team scores the winning point." Eisner warned that Paramount, which had been the No. 1 or 2 studio over the preceding five years, should consider itself in last place.

"You make a deal with those people, I'll kill you," Eisner would bark.

"We should never become bogged down in the vulnerable stagnation of success."

It was imperative, Eisner warned, to "avoid the big mistake." The perfect executive, he continued, is "a 'golden retriever' with good taste." And commercial potential, in Eisner's view, was all that mattered. He stated his own goal in succinct terms. "We have no obligation to make history," he said. "We have no obligation to make art. We have no obligation to make a statement. To make money is our only objective."

Like many high-ranking Hollywood executives, Eisner was inclined to say yes when he meant no. It was not uncommon for Eisner to respond to a pitch with wild enthusiasm and apparently approve it. Then he'd call one of his lieutenants and bark, "You make a deal with those people, I'll kill you." Simpson used to call this ploy "The Elastic Go." Eisner fancied himself as insulating his staff from Diller's tirades, playing "something of a mother's role protecting the children from a brilliant and powerful but difficult and demanding father." But members of Eisner's staff became so concerned about his often conflicting directives that they made a

pact: no one would meet with him alone. That way, there would always be a witness.

Katzenberg's frustrations were evident in a set of notes that he scribbled to himself in March 1980. His harshest words were reserved for Eisner. "First instinct is negative/Approach is to confuse or stall," he wrote. "Refuses to take anyone seriously—everyone has an angle and everyone is out to screw him. His world is the whole universe/there is no room for other opinions/no consideration for other points of view/no other perspective than own. Totally shoots from hip and then tries to create his own set of facts to support.... He is out of control."

In June 1982, Katzenberg was named president of production. The biggest complaint against him was that he had never demonstrated any particular brand of taste or creative instinct. "The thing about Jeffrey that plagued him his whole life is that, smart as Jeffrey is, Jeffrey isn't a guy who can feel it," says producer Craig Baumgarten (Universal Soldier). "Jeffrey will go to a record store, buy the top 10 albums, and listen to them. But he doesn't love them." Another former colleague puts it more harshly. "Jeffrey was always the plodder," he says. Yet another remembers urging Katzenberg to hire a bright young animator at Disney named Tim Burton. "Talk to me when he's established," Katzenberg said.

Katzenberg tried to tackle the creative part of the process through the combined powers of his will and his brain. And no doubt Eisner saw him as a perfect, relentless "retriever." (It didn't help when, after Eisner mused that he'd like to film an adaptation of Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter, Katzenberg admitted that he had never read it.) The other widely held criticism of Katzenberg was that he was only too willing—happy to execute Eisner's mandate to control the filmmaking process and manage costs.

For the time being, though, they complemented each other perfectly. Katzenberg and Eisner cheerfully kept up an enemies list; a former Paramount executive remembers Eisner sticking his head in Katzenberg's office occasionally to ask, "So-and-so called. Do we hate him? Is this guy dead to us?"

Katzenberg's work habits were becoming legendary: the Monday-morning calls to dozens of agents, the back-to-back breakfast meetings, the "if you don't come in Saturday, don't bother showing up Sunday" work ethic that would be emulated by ambitious young suits throughout the industry. "Jeffrey made everybody nervous," recalls Mestres, a Harvard graduate who went on to be a top production executive at Dis-

Michael thought I was moving away from Paramount," Diller says "I had no intention of moving away. That pissed him off."

ney. "Nobody worked the hours or covered the territory that Jeffrey seemed to."

Producer David Kirkpatrick remembers "looking out the window and seeing Jeffrey put his hands on our car hoods to see if they were warm or cold at five in the morning.... We worked 24 hours, but it was thrilling to be a part of it. You were at the center of it all and the bosses didn't mind unmasking their feelings for all to see. That was exciting to a young pisher

But there was a downside, too. Kirkpatrick recalls working overtime on Christmas Eve. When he mentioned that it was a holiday, Katzenberg replied, "So we'll order some turkey sandwiches."

Cinematically speaking, Eisner's and Katzenberg's taste could be spotty—as evidenced by their handling of Walter Hill's 1982 action comedy 48 Hrs. The

film was about a black convict teamed with a white detective in order to catch a killer. The studio had hoped to cast Richard Pryor, but had to settle on a raw young Saturday Night Live comic named Eddie Murphy. From the start, Hill says, he and Eisner repeatedly clashed because Eisner wanted more comedy. One source close to the production says that Eisner continually asked Hill, "Did you put them in chicken suits yet?"—a reference to the famous scene in Pryor's 1980 comedy Stir Crazy.

After viewing some early footage of the film, Katzenberg—the newly named head of production—called producer Larry Gordon, a longtime friend of Eisner's. "We're having trouble with the dailies," Katzenberg told Gordon. "Murphy's not funny." Convinced that Murphy had to be replaced, Katzenberg asked Gordon, "Have you seen the black guy in Airplane IP." He was referring to Clint Smith, an obscure comic who played a scalper in the failed sequel. Gordon wouldn't budge. "It's ridiculous," he told Katzenberg and Eisner. "You guys are crazy."

As a kind of compromise, the producers provided Murphy with an acting coach. (According to the film's costume designer, Marilyn Vance, much of Murphy's dialogue had to be rerecorded after the film was finished because his pacing was off.) 48 Hrs. went on to gross more than $77 million. As for Gordon, his success did not prevent him from getting into a bitter dispute with Eisner over his decision to take his next two projects (Brewster's Millions and Streets of Fire) to another studio. Eisner tried to have Gordon thrown out of his office on the Paramount lot; Gordon got a court order blocking the move, and the two were estranged for years.

Eisner was constantly on the lookout for ways to save money, and no one was immune. James L. Brooks, the television genius who had created The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Taxi, wanted to try his hand at directing a film adaptation of the best-selling Larry McMurtry novel Terms of Endearment, the story of a mother's relationship with her doomed daughter. This was hardly the sort of project which warmed a studio chief's heart. "They always thought, No—cancer. She dies of cancer," recalls producer Lawrence Mark, then an executive at the studio. Diller and Eisner figured the picture could

never outperform one of their earlier grimbut-well-received efforts, Robert Redford's Ordinary People, and they refused to give Brooks the full $11 million budget he wanted, forcing Brooks to find additional financing elsewhere.

Brooks had assembled a spectacular cast—Shirley MacLaine, Debra Winger, Jack Nicholson—but the production quickly turned into a mess. Even before shooting began, Brooks was falling behind on a schedule that was too tight in the first place. To make matters worse, Winger was behaving erratically, possibly because she was ingesting too much cocaine. She also had developed an abiding hostility to her on-screen mother, Shirley MacLaine. One day, the two sat side by side looking at screen tests of Winger wearing various outfits. Winger appeared on the screen in a red dress. "Isn't that cute," MacLaine said, and reached over to touch her costar's arm. Unfortunately, she missed "You grabbed my tit!" Winger shrieked. She punched MacLaine. Alarmed crew members had to pull Winger off her co-star.

It didn't take long for Paramount to panic over the pace of the production. Soon after filming started, Eisner flew to Houston to take a look at what he feared to be ; disaster in the making. He was whisked into a screening room, where he viev some hastily edited footage. Eisner co see that Brooks just might be making an extraordinary film and gave him a bit more breathing room.

But not much. Katzenberg was given the job of enforcer, and he relentlessly hammered on Brooks to hurry up. Debilitating arguments over time and money escalated; the studio constantly threatened to shut down the movie if Brooks didn't speed things along. Meanwhile, Brooks and Winger were barely speaking to each other. At one point, as the studio browbeat Brooks to keep a tight production schedule while on an expensive location shoot in Manhattan, Winger refused to leave her hotel room because she had a large pimple.

Even though early screenings of the film didn't go well, Brooks reworked the picture and transformed it into a major hit. Paramount's projections were shattered when the 1983 picture grossed $ 108 million and won five Oscars.

Charlie Bluhdorn couldn't even die without stirring controversy. When the end came, on February 19, 1983, the official story was that the 56-year-old Bluhdorn had suffered a massive heart attack. There were subsequently various rumors about his whereabouts when he died.

The official line was that he was stricken on his jet while returning from a trip to the Dominican Republic.

The news came as a shock, but it shouldn't have. Bluhdorn was suffering from leukemia—a fact that a major publicly owned company clearly should have reported to stockholders. But if the government was right, this wasn't the first time that Gulf & Western had engaged in questionable conduct. Indeed, Paramount's parent company had in 1981 settled a lengthy investigation by the S.E.C. for allegedly misappropriating funds. The case was settled with Gulf & Western agreeing to improve corporate housekeeping without admitting any guilt.

Bluhdom's successor was Martin Davis, a 57-year-old Gulf & Western veteran who leapfrogged over other high-level executives to take the helm. In the mid-1960s, Davis

Barry is not going to work for anybody. You either give him his candy or you throw him out."

had been a key player in fending off a hostile takeover of the studio led by Herb Siegel. He assembled a committee of friendly shareholders; to head that committee Davis picked an obscure theater owner from Boston named Sumner Redstone.

Barry Differ allied himself with Davis, who had promised not to make changes at the studio. "It was a terrible mistake of mine," Differ recalls. After the board resolved that no one should take Bluhdom's title or his office, Davis did both.

Davis acknowledged that his relationship with Differ quickly soured. At first, however, Differ seemed to be on the rise. In March 1983, Davis promoted him to chief of a newly formed Entertainment and Communications Group, giving him responsibility for Simon & Schuster, the New York Knicks, Madison Square Garden, and the Sega video-game division. The effect on Diller's relationship with Eisner was not salutary. Eisner hoped that Diller's new role would give Eisner more control of the studio, but he was disappointed. "Michael thought I was moving away from Paramount," Differ says. "I had no intention of moving away from Paramount. That pissed him off." Eisner said later that at this time "a chill set in" between him and Differ.

But Diller's added responsibility did not produce the autonomy that he thought he had been promised. Martin Davis could be stubborn to the point of irrationality—a trait that became more apparent as he took over at Gulf & Western. "I became a control freak, which I clearly admit," he later acknowledged. And in the case of Paramount Pictures, he was bent on instituting a new management style. About two months after Bluhdom's death, Davis told Differ that he had always disliked Eisner, and suggested that Differ fire him. Differ declined. "I didn't know Marty Davis—I didn't know his methodology," he says. "That was the way he weakened people—to go after their No. 2 man. For at least six months I fought against Marty Davis, trying to get him not to do this. And I was unshakable. I never told this to Michael Eisner, because I thought it was my job to deal with this. I didn't want to drive him out of the company." Davis, he says, "used Michael Eisner to break me— not that I understood what he was doing, because I didn't."

Davis denied that he was out to "break" Differ; instead, he blamed Differ for allowing his attack on ^ Eisner to continue. "Any feuds and alleged feuds that Michael and I have had should never have happened," Davis said. "I didn't know him and he didn't know me. Barry was very protective. You never saw any of the others in the organization unless [Differ] deemed it necessary."

Despite Diller's insistence that he came to Eisner's defense, Eisner was convinced that Differ was not his advocate. He even suspected that Differ might be undermining him with Davis. Differ says that Eisner simply "was not in possession of the facts." But his relationship with Eisner started to fray. "I so resented being in this position that, in addition to blaming Marty Davis, I blamed Michael Eisner," he says.

By March 1984, Differ was "building up a great image," as Davis resentfully put it. But Davis's jealousy was not the only problem: the studio's very success was undermining it from within. The long-simmering tension between Differ and Eisner was at fuff boil, and their salaries enraged Davis. Both received hefty bonuses every year, and they were splitting more than half of the bonus pool for the entire studio. In fiscal 1984, Diller's take was 31 percent; Eisner received 26 percent. And both were earning seven-figure salaries. Davis made far less. "I wanted that changed," Davis said. "People say I was jealous that they were making more than me. Nonsense. Whatever Barry wanted, he generally got from

Bluhdorn. Not from me. At some point you have to decide. Do you want to be held hostage? Barry is not going to work for anybody. You either give him his candy or you throw him out."

In the summer of 1984, Diller and Eisner appeared on the cover of New York magazine. When the issue hit the newsstands, it was obvious even to casual readers that a spin competition had taken place.

The article provided a memorable snapshot of the executives who made up Paramount's storied management team. Diller was earning $2.5 million a year, Eisner a bit less. (The figure eclipsed Davis's 1983 earnings of $584,699.) Katzenberg was described in an unattributed quote as "a golden retriever." To his chagrin, the nickname would stick to Katzenberg forever.

"That was a stupid story," Davis said of the New York article. At the time, he reportedly started complaining to associates that Diller and Eisner were "overrated and overpaid." Davis, a cold man who was once described by a former aide as having "a tiny, cruel heart," denied that he had made that remark, but said the article was a slap at the rest of the company because it failed to acknowledge the

contribution of others—especially Frank Mancuso, the marketing and distribution chief who still operated, despite Eisner's best efforts, from his base in New York.

As the relationships degenerated, Davis was supposed to be in contract discussions with Diller, Eisner, and Katzenberg. Their deals expired almost simultaneously in late 1984. Months earlier, Davis had had a few conversations with Diller, but neither side pressed for resolution. Diller suggested that Davis start with the junior man and told Katzenberg to fly to New York. When Katzenberg arrived, the negotiation began on a sour note. "I have people in Hollywood who tell me you're Sammy Glick," Davis said. He berated Katzenberg for being gossipy and for lacking creativity. Davis ac-

cused Katzenberg of conspiring with Diller and Eisner against him.

At this, Katzenberg says, he started to laugh.

"What are you laughing about?" Davis demanded.

"Marty, we can't decide what time the sun's coming up," Katzenberg replied. "If you think the three of us can get together to do something about you, you don't understand."

Despite his sarcasm, Katzenberg was horrified by Davis's attack. He also observed that during the entire discussion Davis gazed coldly out of his office window. "He never took his eyes off New Jersey," Katzenberg says. The meeting ended inconclusively, and Katzenberg went to Diller's office to report to his bosses. Though Eisner would later claim that he

was shocked when he heard what Davis had said to Katzenberg, Katzenberg remembers the events differently. As he recalls it, Diller insisted on getting Eisner on the phone before Katzenberg could say a word. When Eisner picked up, Diller looked at Katzenberg and said, "Well?"

"You assholes set me up!" Katzenberg cried. Then Diller and Eisner burst into laughter.

The superficial camaraderie of the moment did nothing to dispel Eisner's distrust of Diller. "Barry's taking care of Barry," Eisner said, according to Katzenberg. And even in his junior position, Katzenberg could read the silence whenever he asked Diller for reassurances about the future. Diller would tell him, "Hang in there. It'll all be O.K." But he never told Katzenberg what he wanted to hear: "You'll always have a place with me."

Eisner had started to cast about for his next position. He had called Roy Disney to ask whether there might be a job for him at the then faltering studio. Disney was in the midst of a takeover battle, however, and the outcome was uncertain. (The company tried to expand by purchasing the Arvida real-estate company and by briefly attempting to purchase the Gibson greeting-card empire.) Eisner's preferred option was to start his own film company with financing from his old friends at ABC. Eisner and

Diller never told Katzenberg what he wanted to hear: "You'll always have a place with me

Katzenberg started working out a business plan and registered their company's proposed name: Hollywood Pictures.

For Diller, the escape route amounted to changing a single consonant—from Martin Davis to Marvin Davis. He started negotiating with the latter Davis, the outsize Texas oilman, about taking charge of Twentieth Century Fox. Meanwhile, the Davis who ran Gulf & Western pressured a reluctant Diller to promote Frank Mancuso. Rather than report to Eisner, he would report to Diller. Katzenberg would then report to Mancuso as well as

to Eisner. Katzenberg was infuriated, but Diller tried to reassure him that business would be conducted as usual.

Martin Davis arrived in Los Angeles on Monday, September 3, 1984. He had some inconclusive discussions with Diller about his contract and then met with Eisner. When Davis reiterated his complaint that Diller and Eisner were being paid too much, Eisner responded, "I think you're being paid too little." The uncomfortable conversation went nowhere. Next, Davis met with Katzenberg and took a different tack. Davis, perhaps hoping to retain one remnant of the Paramount dynasty, apologized for his earlier diatribe.

The following Friday night, top Paramount executives gathered for a dinner in Davis's honor at Diller's Coldwater Canyon house. It was obvious that—however successfully Diller had run the studio and however effectively he had romanced the publications which spoke most directly to Wall Street—Davis was going to 1 mow him down. Given all the simmer' ing hostilities, the dinner party was not pleasant. "It was the most tense social engagement that I've ever been at," recalls one of the executives who attended. Katzenberg remembers the evening as "genuinely terrible. Just pain."

On Monday, September 10, Diller announced that he was leaving to become chairman and chief executive at Twentieth Century Fox. Eisner was stunned. "Michael didn't know," says a former Paramount executive. "I think Michael felt completely betrayed because Michael had been assured by Barry that he'd be defended." Even though Eisner had not relied on those assurances, he was angry and upset that Diller had frozen him out.

Diller maintains that he had told Eisner a month earlier that he was in talks about going to Fox and even asked Eisner to join him. At the time, Eisner had other irons in the fire and was hoping that he would finally step out of Diller's shadow. Regardless, Eisner clearly thought that Diller should have told him by the night of his party that his departure was imminent. Diller says he held back because he had not quite made up his mind. "I was 98 percent gone—99M percent," he asserts. "I had not signed a deal with Fox. I did not sign until Sunday."

The next Monday evening, Davis called Eisner at home and asked him to fly to New York at once. Eisner stalled. "I can't come tonight," he said. "It's my son's first day of school tomorrow." Davis said he should come the next day. "Are you going to ask me to report to Mancuso?" Eisner asked. Davis said that nothing had been decided. Diller says he implored Eisner to

stay home: "I said, 'Don't go to New York. Marty Davis is going to repudiate you.' And Michael didn't trust me. He thought I was probably manipulating him to get him to go to Fox with me."

By coincidence, Eisner's former boss at ABC, Fred Silverman, was in Eisner's office and witnessed some of these discussions with Diller. Both men were very nervous, he recalls. "They talked about Davis like he was Vlad the Impaler," he says. On Tuesday afternoon, Eisner and Katzenberg flew to New York—commercial. They spent the flight hoping that Davis would breach Eisner's contract, which required Paramount to consider Eisner for the top job if Diller left. If Davis passed Eisner over, Gulf & Western would have to pay Eisner to go away.

Rich Frank, president of Paramount's television division, had also been summoned to New York. It was late at night

"Eisner and Diller talked about Martin Davis like he was Vlad the Impaler."

when he was ushered into Davis's office in the Gulf & Western Building. To Frank's shock, Davis peremptorily told him that the top job at the studio was going to Mancuso. "Michael's a child," Davis said contemptuously. "If I put blocks on the floor, Michael would sit down and play with them."

Frank told Davis that he was about to commit a blunder that would become textbook material at the Harvard business school. Just as Frank was leaving, Eisner and Katzenberg arrived. They were put into separate offices and told to wait while Davis conducted successive meetings.

Eisner walked into Davis's office just after midnight. According to Davis, Eisner "fought like hell" for the job. Eisner does not remember waging any battle at all. Both agree that Davis asked Eisner if he would report to Mancuso, and Eisner said no. When the meeting ended, Davis did not sound as resolute as he had been when he spoke to Rich Frank. "I'll have to sleep on it," he told Eisner. Then Katzenberg had his turn. Davis again expressed his view that Eisner was simply an overgrown child, but repeated that no decision had been reached about the top job. He asked Katzenberg for a commitment to stay after his contract expired. Katzenberg said

he couldn't give him an answer on the spot.

Later, Eisner and Katzenberg commiserated at the Brasserie, an all-night restaurant in the Seagram Building on East 52nd Street, and then Eisner went to the Mayfair Regent. (Katzenberg preferred the Regency.) By now it was the wee hours of the morning. On the way to his hotel, Katzenberg picked up an early edition of The Wall Street Journal. There it was in black and white: a report that Frank Mancuso would be named as Diller's successor.

Katzenberg frantically called Eisner's room to tell him the news. Then Eisner called Diller at home in Los Angeles. "I said, 'Sorry to tell you, I told you so,'" Diller says. "Eisner was devastated. He was publicly repudiated."

Eisner may have been upset, but he was hardly incapacitated. He maintained that his contract guaranteed him the right to be considered for the top job if it became vacant. Now Eisner argued that Davis had never really given him that opportunity. He demanded that the studio forgive certain loans—such as the $1.25 million that Eisner had borrowed for his house in Bel Air—and make payments that were due to him. Eisner sat in Davis's office and refused to leave until he was given a cashier's check for the full amount: $1.55 million.

He got it. That afternoon, he and Katzenberg strolled to Chemical Bank and promptly deposited the money. ("His contract had expired," Davis said. "But he did have money due him.") Despite all the signals that Davis was more than willing to let Eisner go, Eisner felt deeply betrayed. He was so anxious that he insisted that Chemical deposit the money as cash, immediately.

Diller says that he asked Eisner to join him at Fox. And according to Diller, Eisner agreed to take the job, and even negotiated a contract. But Eisner must have figured that he would be an afterthought at Fox. Diller's move had already made a splash; his deal was the richest in Hollywood history ($3 million a year, plus a stake in the company's growth). Eisner was not prepared to again work in the shadow of Barry Diller. Meanwhile, Eisner denied a swirl of rumors that he was headed for Disney.

By now, one thing was clear: the dynasty at Paramount was over. At 42, Diller was off to Fox, where he would eventually defy skeptics by launching the fourth television network. And, as it turned out, Eisner and Katzenberg would soon become almost synonymous with Disney, where over the next decade they would engineer one of the most dazzling corporate turnarounds in the history of business.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now