Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

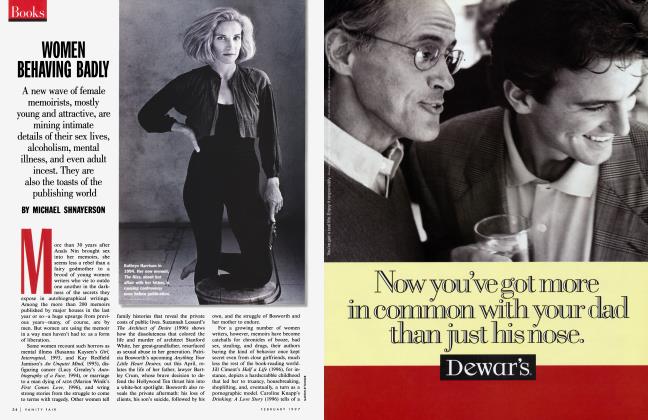

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowHOLLYWOOD VERTIGO

Hollywood is experiencing power gridlock, with empires, egos, and mega-movies colliding left and right— Murdoch vs. Turner, Redstone vs. Bronfman, Volcano vs. Dante's Peak, Ovitz vs. Disney. No wonder the latest "object of desire is that which can get them out of town fastest: Gulfstream's new, $36 million G V jet

KIM MASTERS

Letter from L.A.

ou didn t find it in your Neiman Marcus catalogue, but it's what the moguls really wanted for Christmas this year: a bargain at a mere $36 million, the fabulous new GulfI stream Vjet.

The G V is definitely a big improvement over the puddle-jumping, $26 million G IV, so, naturally, the waiting list is long. MCA's Edgar Bronfman Jr. gets the very first one. Also on the list are David Geffen (who sold his G IV to his DreamWorks company); Roy Disney (who will finally be able to go nonstop from L. A. to his castle in Ireland); Steven Spielberg (because he's Steven Spielberg); and Time Warner (upholding a proud Warner Bros, tradition of having a seriously cool jet fleet).

It's not that the G V is bigger than the GIV or that much faster. But it flies farther, enabling moguls to go from Los Angeles to London or Tokyo nonstop. It also flies higher, cruising at 51,000 feet—above air traffic and even the weather. Alas, the new planes won't roll down runways until next year, and there is a backlog of 70 orders. If you sign up for one this very day you might manage to take delivery by the end of the century. But don't forget your nonrefundable $2 million deposit.

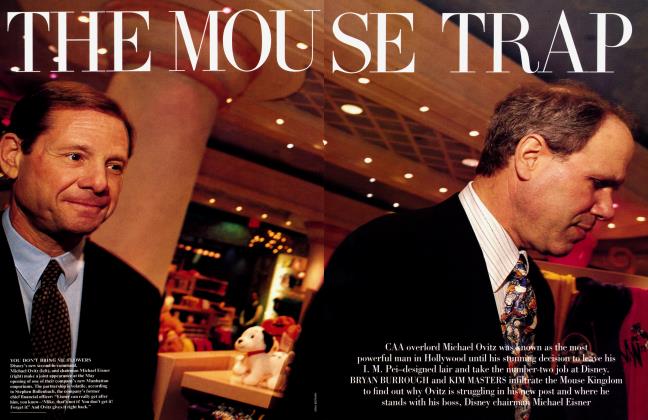

X he moguls have been cranky lately. I Some old friends have parted ways. I After only 14 months, Disney's Era of the Two Michaels (Eisner and Ovitz) has closed. There was nary a moist eye in the Disney kingdom as executives learned that Ovitz was out—just two days before his 50th birthday. Given the demands of playing second-incommand to Eisner, there was perhaps a brief moment of sympathy for Ovitz, who had fallen so far so fast. But the troops revolted when they were told that Ovitz had walked away with a severance package worth a reported $90 million. Suddenly holiday bonuses, which in some cases were less than last year's, seemed like lumps of coal.

What wasn't immediately clear was whether the $90 million figure, reportedly originating from Ovitz's flacks, was real. Disney was silent after the first reports, but as protest grew louder, some top executives claimed that the payoff was closer to $30 million; the larger amount, they contended, was just Ovitz being Ovitz. There was even said to be a letter of understanding outlining the deal. Studio chief Joe Roth implored Eisner to release the letter, hoping to placate the disbelievers. After all, Disney is a publicly held company, and Ovitz's take, if the $90 million figure was accurate, would equal TA percent of Disney's fiscal-1996 net income. A sum of that magnitude would, arguably, have to be disclosed.

As the days passed, the executives who proffered the $30 million estimate started wriggling again, but the company refused to take the simple expedient of explaining the deal. Yet within a week of the announcement of Ovitz's departure, as the topic of his severance raged on both coasts, the Disney brass decided to come clean in a January filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission. This filing discloses that the $90 mil 1 ion figure might, in fact, be conservative. Upon his hiring, Michael Ovitz was promised $1 million per year in salary and options on three million shares of Disney stock. He would receive options on another two million shares unless his deal was not renewed after five years. In that event, he would receive $10 million in cash. In the highly contentious negotiations, Disney declined to give him any guaranteed bonuses or special restricted stock—or any compensation for his stake in the Creative Artists Agency, all of which he bargained for.

Ovitz's final settlement will give him a total cash payment of nearly $40 million: about $3.5 million in salary, $10 million for the stock options he would have been granted had his contract been renewed, and around $25 million in bonuses. He also keeps the options on the three million shares (customarily Disney executives must sell if they depart), which were worth more than $40 million as Ovitz took his leave. Disney stock, however, has historically increased its price. Obviously the market is volatile and Ovitz could sell at any time. So the value of the options is a moving target. But one thing is clear. A compen. sation scheme meant to en/ courage success has, in this case, done the opposite— to a spectacular degree.

Ovitz was able to use the kinds of terms he had established in his failed negotiations to head Sony in 1989 and MCA in 1995 to cut his Disney deal. Aside from the primary mistake of overestimating Michael Ovitz's adaptability, Disney erred by sealing this extraordinary arrangement with a man who had virtually no place to go.

Disney feels that it has had a tumor expensively removed, but believes that the man who was formerly considered Hollywood's most powerful has hurt himself as well. Because he publicized Disney's largesse, the company—which had previously hoped to set him down easily—decided to disclose that he was terminated. So much for the fiction that Ovitz's fade-out was voluntary. The board was determined to fire him and worried that Eisner, his old friend, would be reluctant to pull the trigger. Disney would have liked it if Ovitz had gone quietly. But again, they misunderstood the man.

A n another runway, Rupert Murdoch 11 played name-calling games with his U cable rival, Ted Turner. Murdoch has found ways to intimate that Turner's behavior has been occasioned by a lapse in his lithium dosages. Late last year, Murdoch's rival gave his employees at Turner Pictures reason to ponder this as he woke up after the merger of his Turner Broadcasting company with Time Warner and concluded that he no longer needed the film unit, notwithstanding his earlier assurances to the staff and a battle with Time Warner to keep the unit alive. The stunned employees found themselves sacked before they even had a chance to release

"Edgar is not stupid, but he is unsophisticated in these matters, ^ and Sumner is incredibly sophisticated and one of the best lawyers around."

Michael the picture that was originally to have launched the division. At least Turner Pictures executives won't have to figure out what to do with the frozen buffalo meat the boss sends to employees at Christmas.

What an interesting situation it is, having Turner under the same corporate roof with straitlaced Time Warner chairman Gerald Levin. Already there has been a rumor that Turner danced on Levin's desk in his socks. (A Time Warner spokesman concedes that he doesn't know if this happened, but acknowledges, "There's nothing that would surprise me.") Turner has been assessing the Time Warner culture, looking for ways to curtail spending. And where in particular has his eye fallen? The planes, boss, the planes. Time Warner maintains that it already had plans under way to sell off its two Challengers plus the helicopter, diminishing its fleet of seven flying machines to two G IVs and two G Vs, one of each per coast.

"Those who anticipated trouble between I Levin and Turner haven't actually gotten I to see it yet. But everyone else, it seems, is going at it hammer and tongs. An all-out war erupted when Bronfman sued Viacom, maintaining in a Delaware court that the conglomerate's chieftain, Sumner Redstone, had acted in bad faith by operating a number of cable networks on his owndespite an alleged agreement that the two would partner in any channels operated by either company. Redstone responded by hinting, under oath, that Bronfman is not only disingenuous but a bit of a dim bulb.

At issue is whether when Redstone bought Paramount in 1994 he also bought into a pre-existing agreement stipulating that Paramount would operate cable channels only in partnership with MCA. (The two companies jointly own the USA Network and the Sci-Fi Channel.) But Redstone had been running MTV and Nickelodeon

long before he bought Paramount, and MCA didn't try to muscle in. Sid Sheinberg, former MCA president, says he didn't want to fight about it, because "lawsuits are unpredictable" and the two companies have too many mutual business interests that could have been upset. It was like a marriage, he explains. "You have a fight with your spouse and you've got a child, you may well be more cautious in seeking legal recourse. I elected to do nothing, but maybe I was wrong."

Then Redstone started a new venture— TV Land—without cutting in MCA. He argued that TV Land wasn't actually a new network, just an offshoot of "Nick at Nite" that wouldn't hurt the USA Network at a"-Having said that, Redstone was confronted in court with notes written by one of his own executives asserting that TV Land would indeed try to capture viewers from the USA Network. Redstone suggested that those notes were written by a flunky who didn't really know the views of senior management. Who was that flunky? Richard Cronin, president of TV Land. Redstone admitted that the notes were "embarrassing."

ronfman hardly walked away unscathed. In fact, he had to concede any number of points, making him appear somewhat confused. Aside from waffling on larger issues—such as whether MCA even needs a cable network—he acknowleged that he had "tuned out" Redstone last year when the two went to dinner with their wives at La Grenouille in Manhattan. He said he thoughti it was impolite to talk shop. But Redstone says he was trying to discuss TV Land.

Bronfman also fared badly when the men met last February to discuss the fate of Frank Biondi, whom Redstone had just dumped as chief executive of Viacom but still held in the shackles of a noncompete provision. Bronfman wanted to hire Biondi as chief executive of MCA and said he would waive the right to sue Viacom over TV Land if Redstone would let him go. In the course of these talks, Viacom deputy chairman Philippe Dauman spoke of Bronfman's waiving the right to sue over "MTV." Bronfman testified that he thought this was just a "verbal slip"; he believed that Dauman was confusing the two networks. In fact, Viacom clusters all its cable channels under the MTV designation, so while Bronfman thought he was promising not to sue over TV Land, Dauman was extracting a much broader agreement that Bronfman wouldn't sue for part ownership of any of the cable networks.

"Edgar's a high-school dropout and Sumner is a professor of law at Harvard University," observes one MCA insider philosophically. "That's the real story. Edgar is not stupid, but he is unsophisticated in these matters, and Sumner is incredibly sophisticated and one of the best lawyers around." He adds that this sort of spectacle can hardly benefit Bronfman or Redstone. "Did Sumner try to trick Edgar? Of course," the insider believes. "Should Edgar have known about it? Of course."

Industry analyst Harold Vogel of Cowen & Co. says that the Seagram heir's bout with Redstone will soon be forgotten. And a source familiar with Bronfman's thinking contends that outside the courtroom he has taken some credible steps. While MCA may not win the medal in television or movies, Bronfman figures the company can be No. 1 in music and run a convincing second to Disney in theme parks. He made a good start on reconfiguring the company when he bought half of the chartbusting Interscope Records (cast off by Time Warner in the gangsta-rap panic). There's still reason enough to cut Bronfman some slack, even though the DuPont stock that Bronfman sold to finance the MCA purchase has now increased in value by something like $2 billion. At that rate, you could see how Seagram's shareholders might get nostalgic for the days when they weren't in showbiz.

T he ouster of Ovitz represents one of the I most stunning reversals in the history I of show business. It was shocking to consider that the man who had fashioned the Creative Artists Agency was unem-

ployed, although the litany of errors that led him to this pass is by now familiar, starting with the disastrous effort to lure programming executive Jamie Tarses from NBC. The allegation was that Tarses, under Ovitz's tutelage, threatened her boss, Don Ohlmeyer, with sexualharassment charges so he would release her from her contract. Ovitz partisans now point out that by checking himself into rehab Ohlmeyer has acknowledged that he has some problems. But those who still tell the tale about Tarses (she denies making the threat) should ponder this question: If Ohlmeyer was guilty of sexual harassment, would it be better to stand accused of exploiting it to gain an advantage in a negotiation or of ignoring it because of his power?

Then there were Ovitz's much-publicized problems with Kundun, the Martin Scorsese movie about the Dalai Lama, which Universal had rejected because of fears that it would offend the Chinese and jeopardize forays into that potentially vast market. Opening China for Disney was one of Ovitz's few defined responsibilities at the company, and he complicated that mission for a picture with uncertain commercial prospects. Ovitz allies point out that the Chinese backed down from threats to retaliate against Disney, meaning that Ovitz struck a blow for the American way. But Eisner could not have been happy. Fox is a good case study of the vagaries of this high-stakes game. The studio has plunked down the better part of $100 million for its volcano movie, cleverly titled Volcano, which it sent into production despite the fact that Universal had started Dante's Peak, its own $100-mil lion-plus volcano movie, a month earlier. Universal, hoping to beat Fox into theaters, decided to spend an extra $10 million to ensure a March opening. Then Fox announced that it would go even faster, opening its picture in late February. But Fox has also scheduled the re-release of the Star Wars trilogy for late January and early February. These are crucial openings for Fox, since the executives there also hope to persuade George Lucas, creator of the intergalactic sagas, to allow them to distribute the next installments in the epic. With Fox locked into the Star Wars dates, Universal saw an opening and spent another few million to leapfrog again, announcing that its volcano movie would open February 7. Obviously, Fox couldn't move its movie earlier than that—it would crash into Star Wars. And it couldn't move Star Wars without riling Lucas. Checkmate.

Titanic m\\ surpass Waterworld asthe most expensive picture ever.

Adding up Ovitz's trespasses, Disney executives confirm that Eisner was incensed when he discovered that his second-in-command was secretly negotiating to take a job running Sony—a play that collapsed, according to a source close to the situation, when Ovitz overreached in his demands. But even aside from these missteps, Ovitz's detractors felt that he was simply not getting it as an executive at a publicly held company— that he was wasting time and money and ultimately adding to Eisner's burdens instead of sharing them. The opposing camp holds that Eisner, unwilling to let the reins slip an inch, wouldn't tell Ovitz what to do. And when the man who was supposed to be his longtime friend showed signs of distress, Eisner only undercut him further.

fl learly, Eisner became disenchanted with I Ovitz in fairly short order, and as the U press scrutiny intensified, he barely feigned support for his supposed "partner." After this magazine detailed Ovitz's troubles at the company, Eisner told associates that the article was well reported and even well written. According to one knowledgeable source, Disney became so inhospitable to Ovitz that chief financial officer Richard Nanula even investigated who paid for an Ovitz family party (his daughter's Bat Mitzvah) at the House of Blues. A Disney executive says the company was merely checking to see if the nightclub—partially owned by Disney—was giving improper discounts to company employees. (They found nothing amiss.)

Ovitz apparently will look for a business opportunity that will spare him the trouble of dealing with a boss. Investment banker Herbert Allen could back him. "Certainly if he comes to us with an idea, I'll be happy to," Allen says. One wonders if these two are waiting for Sony president Nobuyuki Idei to tire of Hollywood so that Ovitz can run Sony's entertainment company after all. Once again, part of Columbia Pictures would belong to Allen.

A umner and Edgar. Murdoch and Tur\ ner. Michael and Michael. Can it be U that money doesn't buy even a hint of good fellowship? Part of the problem is that the media world is simply too hideously competitive. Blockbuster movies are slamming into one another. Analysts calculate that right now the studios are producing nearly a dozen pictures with budgets exceeding $100 million.

Fox blinked and postponed Volcano's, release. And if that weren't enough, the studio has the very expensive Speed II, plus another, even scarier extravaganza, on its hands. For its major summer release, Fox has teamed up with Paramount on James Cameron's Titanic, a picture that will surpass Waterworld as the most expensive ever made. The budget is rumored to be climbing north of $170 million. Cameron, the obsessive director of Aliens, the Terminator series, and The Abyss, is cranking away in Mexico, behind schedule and way overbudget.

A Fox executive acknowledges that the studio can't really hope to make money on this picture. Why do it? Because, he says, Fox will make out on Cameron's next couple of projects, which (so the studio believes) are wildly commercial and at least theoretically cheaper.

tflony reintroduced itself to the world not \ long ago, holding a press conference feaU hiring its president, Nobuyuki Idei, and his management team, headed by veteran executive John Cal ley, late of United Artists. The event may have conveyed some messages that it didn't intend to send. Former ambassador Walter Mondale said recently that he had known Japanese culture was different before going to Tokyo, but that he didn't really get it until he arrived there. The Sony press conference managed to remind some observers of that cultural division. The American press has been fond of saying that Idei speaks fluent English—and no doubt his English is better than, say, Michael Eisner's Japanese. But there was some linguistic confusion. Here is the exact transcription of one of Idei's opening remarks: "This is first week of John Cal ley to the Sony Pictures Entertainment." Idei has a heavy accent, and when he started to talk about "value chains" (a somewhat nebulous concept that has replaced the old and equally murky Sony mantra, "synergy"), the press began whispering nervously as they attempted to make out his words. Sony, in fact, declined to release a transcript of the proceedings until it was tidied up.

Idei was quick to distance himself from errors made by previous management and even said, "I don't understand the name of synergy"—so in that respect he's on the same page as most everybody else. But the press briefing really only reinforced a sense that Sony remains very foreign to the ways of Hollywood.

Idei was quick to distance himself from Sony's previous management and said, "I don't understand the name of synergy."

Whether Cal ley can turn that ship around is an open question. The man has certainly classed the place up a bit, and he has many relationships and oceans of goodwill inside the entertainment community. On the other hand, he took a long break from the industry when he retired from Warner's in 1980, and didn't really get back into the game until he took over United Artists in 1993. He had some hits and misses there, but the chief of one entertainment firm observes that his job didn't have the sweep of a studio chairmanship as we now know it. Here's a guy from the 60s and he got dropped into another world," this executive observes. "Home video didn't exist, pay-per-view didn't exist, cable had just started, and international revenues were, like, 20 cents on the dollar." Apparently, Idei isn't worried. At least not as worried as Ovitz and Allen might want.

1 nd what of DreamWorks? Jeffrey Katz/I enberg's plan to build a world of his /1 own has hit a rough patch. Since a March groundbreaking, the ambitious $8 billion Playa Vista development that is supposed to be home to the state-of-the-art DreamWorks studio has stalled. The first spade on the DreamWorks "campus" has, in fact, yet to be turned.

In November, Katzenberg went to war with developer Robert Maguire, charging that "greed" is bollixing up the project. Maguire, who seems to be besieged by financial problems, had insisted on maintaining control of the project, blaming all the delays on lawsuits filed by environmental activists. Katzenberg vowed that the DreamWorks partners would find another site unless Maguire took himself out of the picture.

The power of DreamWorks was soon made manifest. IBM, the development's "technology architect," pulled out of the deal, demanding that Maguire produce $430,000 in fees that were "seriously past due." IBM said it wanted nothing to do with the whole thing as long as Maguire was in charge. Los Angeles city councilwoman Ruth Galanter wrote to Maguire to remind him that some $70 million in incentives offered by local government would disappear if DreamWorks didn't get its way. Within a month, Maguire had given up, accepting a seat on a three-person committee that will now run the project. Katzenberg says DreamWorks is still hoping to get the development back on track.

Katzenberg's assault on Maguire is child's play compared with what he'd like to do to his former bosses at Disney. Katzenberg's lawsuit claiming that he's owed profits from films made during his tenure as Disney studio chief gained moral validity after reports of Ovitz's golden good-bye. After all, if Ovitz gets $90 million for 14 singularly unsuccessful months, shouldn't Katzenberg get a big payoff for 10 profitable years? At the stipulated Ovitz rate, he's entitled to something like a billion dollars, but in his pending lawsuit, Katzenberg says he's willing to take a mere $250 million. "This ensures that Jeffrey is going to go for the last nickel," says one Disney executive.

Meanwhile, Eisner isn't budging, and many are hoping for the mother of all wars. A trial seems to be about a year away, and one executive predicts, "This will be for Hollywood what O.J. was for the country." □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now