Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

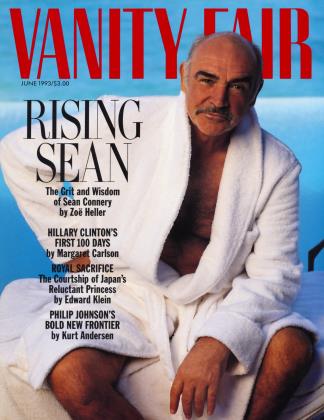

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThis month, Harvard-educated, fast-track diplomat Masako Owada marries Japan's Crown Prince Naruhito—and loses the freedom for which she fought so long

June 1993 Edward KleinThis month, Harvard-educated, fast-track diplomat Masako Owada marries Japan's Crown Prince Naruhito—and loses the freedom for which she fought so long

June 1993 Edward KleinFor years, Crown Prince Naruhito had been searching in vain for a bride. "I'm probably going to challenge Prince Charles for the gold medal in marrying late," the heir to the Japanese throne complained last year on his 32nd birthday. The royal computers in Tokyo continued to comb through the family trees of illustrious candidates, but every time the prince displayed the slightest interest, the young woman in question would deliver a polite rebuff, or marry somebody else, or threaten to commit suicide, or, in one celebrated case, flee the country without leaving a forwarding address. At his wit's end, Naruhito turned to his mother for advice.

The emperor and empress normally live behind a huge moat in the center of Tokyo, and a private audience, even one with a son, involves an elaborate caravan of cars and security guards and the permission of court officials. But since new living quarters at the Imperial Palace were under construction last year, Emperor Akihito and Empress Michiko were in residence in the nearby Akasaka Palace compound, whose stands of silver-birch trees provided Crown Prince Naruhito with the floral pattern of his imperial seal. It was late in the autumn, and the last leaves were falling as Naruhito trudged to his mother's chambers.

She greeted him warmly. Of her three children—the crown prince, Prince Akishino, and Princess Sayako—Naruhito was her favorite, not only because he was her firstborn, but also because he was, in her eyes, a shining example of moral rectitude. Michiko had been educated strictly in Roman Catholic schools, and though she probably never discussed intimate sexual matters with her children, she had reason to suspect, as did many others in Japan, that the crown prince, who hadn't been left unattended since the day of his birth, was still a dotei, or virgin. Now approaching his 33rd birthday—a time when he could claim that gold medal from Prince Charles—Naruhito was the oldest unmarried heir apparent in the history of the Chrysanthemum Throne, a dynasty that stretched back in an unbroken line of succession for more than 1,500 years. People were starting to talk about an imperial crisis.

The servants withdrew, leaving the empress and crown prince alone. Reliable accounts of what transpires between members of the Japanese imperial family are extremely rare. The peerage in Japan was abolished after the Second World War, and the remaining royals—about two dozen in all—are rarely seen in public, and then mostly on ceremonial occasions. Unlike the unruly mob that makes up the House of Windsor in Britain, the Japanese are very self-disciplined, and they don't display the slightest tendency to blab in public or get into trouble. Their few friends are reluctant to gossip about them for fear of being easily identified, and consequently banished from court. As a result, on my most recent trip to Japan, where I once lived and learned to speak the language, the people who shared confidences with me for this story did so on the condition of strictest anonymity.

Sources close to the palace described the crown prince as an impressive young man—intelligent, educated, and highly cultivated. But they also said they believe he has a maza kon, or mother complex, and is excessively dependent on the empress, finding it hard to live outside her shadow. He told his mother of his fear that he would never marry and produce an heir. He felt like a failure. His biggest nightmare was that he would become the last emperor of Japan.

The empress listened, then turned to her son and reportedly said, "You must follow your feelings and marry Masako Owada."

This was exactly what Naruhito wanted to hear, for Masako Owada had long been his first choice as the princess bride. He had met Masako six years earlier, and he looked upon her as a kind of superwoman: she had spent many of her formative years in America, she knew five languages, and she had earned degrees from both Harvard and Oxford. She also had a successful career in the foreign ministry, which was administered on a day-to-day basis by her father, and there were those who thought she might even go all the way to becoming an ambassador.

She had a large nose and dark skin, and her fellow Japanese often mistook her for a Filipina or Nepalese. But with her short skirts and long stride, the 29-year-old Masako fit the image of the liberated Japanese woman. And it was precisely her divergence from the norm of female submissiveness that attracted Naruhito.

There was only one problem: the highly ambitious Masako had her own agenda, and she had already rejected the prince's offer of marriage.

The empress decided to take matters into her own hands. Early one morning a few days later, her limousine slipped through a gate of the Akasaka Palace. Michiko was concealed behind linen curtains in the backseat; she didn't want anyone to know that she was on her way to a secret rendezvous with Masako Owada.

With each passing year, the empress seemed to become thinner and more elegant. At 58, she resembled one of those frail but powerful female figures from the spirit world who turn up in so many Japanese movies. Her car traveled along Shinjuku Dori, the same route she and her husband, Akihito, had followed in a gilded horse-drawn carriage more than three decades before on the day of their wedding.

With friends, she sometimes alluded to a feeling that she herself was to blame for her son's marital predicament. As the first commoner to marry a future emperor of Japan, Michiko had suffered greatly in the Imperial Palace, enduring endless taunts at the hands of envious royals, including her mother-in-law, the former empress Nagako. Practically everyone in Japan knew that Michiko had had a nervous breakdown and an attack of aphasia that left her temporarily unable to speak. It was hardly surprising that most young Japanese women, clinging to the fragile strands of their new liberation, were far from eager to follow in her footsteps.

Michiko's limousine turned into an affluent neighborhood and drew up in front of the house of Isamu Kamata, a retired businessman and amateur composer, who frequently accompanied the empress and emperor to classical concerts. (Kamata refused to take my phone calls and was not a source for this story.) Michiko was ushered inside, where she removed her shoes and found Masako Owada waiting for her in a room set aside for guests.

According to one account, Masako had dark splotches under her eyes, and looked as though she hadn't slept in days. For the past week or so, she had remained secluded in her parents' modem concrete-and-glass home in the Meguro section of Tokyo, fielding frantic telephone calls from the lovelorn crown prince.

The empress and Masako had a great deal in common. Both came from progressive-minded families in which foreigners and foreign concepts were embraced with enthusiasm. As part of their training in Western culture and ideals, both had been educated in the same Catholic school system, run by the Sisters of the Infant Jesus of Saint Maur. And they were both acquainted with a revered teacher at the Denenchofu Futaba School, a woman named Mrs. Mori. Although Mrs. Mori was now retired, she had recently taken to telephoning Masako to talk to her about the principle of being of service to others.

There was only one problem: Masako had already rejected the prince's offer of marriage.

The empress's conversation with Masako wandered to the subject of the British royal family, and the two women noted that the British, upon whom the Japanese had once modeled their own royal institution, seemed to have forgotten the principles of which Mrs. Mori spoke—duty, service, and self-sacrifice. "We mustn't allow that to happen here in Japan," the empress reportedly said.

Good Catholic-school product that she was, Masako soon realized that the empress was asking her to do what she had been taught by Mrs. Mori and the nuns: sacrifice herself for others. It was a spiritual appeal, and it brought Masako close to the breaking point. From earliest childhood, she had been trained to surrender her personal desires to something higher, whether to her parents, to her school group, or to God, and now she was being asked to do the same for her country. She wondered out loud: wouldn't she suffer the same horrible fate as the empress if she married the crown prince?

"As long as you are true to your own feelings and hold on to your own opinions," the empress told Masako, "you will have absolutely no problem whatsoever. ' '

There could be no mistaking the empress's meaning. She was offering Masako her personal promise of protection if she would marry her son. The two women looked at each other in silence for quite some time. Then, in the most exquisitely polite Japanese, they began discussing the specific terms of the marriage.

A few days later, on December 12, Masako left her home in a car driven by one of her twin sisters. She switched cars several times to avoid being followed, then climbed into a maroon station wagon waiting for her in front of a hotel. She was driven to the crown prince's palace.

"Tsutsushinde o-uke itashimasu," she said when she was alone with Naruhito. "I discreetly and humbly accept."

Word of her acceptance soon leaked to some members of the press, but nothing appeared in print or on television for nearly a month, because the reporters had agreed to a total news blackout on the bridal search. The moratorium had been requested by the Imperial Household Agency, the powerful and secretive arm of government that controls the imperial family as though they were so many Bunraku puppets. This wasn't the first time the reporters had muzzled themselves; they had gone through the same routine three decades before, when Naruhito's father, Akihito, was hunting for a bride.

But the Japanese aren't quite as rigid as they are often portrayed in the West, and they have devised many creative ways of getting around their society's severe demands for conformity and group harmony. In this case, either a Japanese reporter or a government official slipped the royal scoop to Shigehiko Togo and T. R. Reid in the Tokyo bureau of The Washington Post, and even though the Post's exclusive was buried on an inside page, the embargo and all hell broke loose in Japan.

Five out of six television channels in Tokyo interrupted their regular programming at almost the same instant and switched to hours of canned bios of Naruhito and Masako. Anchormen popped up in newsrooms decorated with bridal veils and wedding cakes. Newsstands displayed commemorative editions that had been laid out well in advance. Magazines seemed to appear overnight with dozens of pages of color photos of Masako, chronicling the milestones of her life, from birth to foreign ministry.

Everyone fell into line. Japanese intellectuals of every ideological stripe, including staunch anti-monarchists, turned up on TV talk shows to applaud the choice of Masako Owada, who, they predicted, would be a role model for women and an agent of revolutionary change in the male-dominated Japanese family. Some even speculated that Masako would finally open up the imperial family and, in the process, democratize and internationalize the entire nation.

In the midst of this gusher of public relations, the country was treated to a romantic poem that Crown Prince Naruhito had entered in the annual imperial poetry contest:

I gaze with delight As the flock of cranes take flight Into the blue skies. The dream cherished in my heart Since my boyhood has come true.

But if the Japanese were enchanted by the modern-day fairy tale, they were also thrown into temporary confusion. They couldn't fathom why a career woman such as Masako, who had lived alone overseas as a single girl, would surrender her freedom to the antediluvian Imperial Household Agency. "The day after the announcement," said a former U.S. diplomat, "a Japanese journalist was in my office, and I asked him, 'What do you think?' He lowered his voice, as if the emperor could hear, and he said, 'Poor girl, poor girl.' " Even Masako's mother seemed to share this attitude. Asked to describe her emotions over her daughter's betrothal, she said, "I don't know whether to feel happy."

It didn't take long, however, for people to adjust to Masako's transformation from reluctant bride to dutiful fiancée. She quit her fast-track job to prepare for her June wedding. She stopped answering phone calls from old friends. She didn't leave her home, except to go to the Imperial Hotel, where she had her official photograph taken, and to go inside the moat to the damp and gloomy building occupied by the Imperial Household Agency, where she began 50 hours of instruction in such esoterica as palace ceremonial rituals, the imperial legal system, Japanese waka poetry, calligraphy, and the traditional manners of the court. Neither she nor anyone else seemed to think it unnatural when her own sisters, speaking to the press, began employing the stilted form of honorific language to discuss Masako, even down to her elementary-school grades.

At last Masako appeared at a televised press conference with the crown prince, entering a few respectful steps behind her future husband. Gone were the short skirt and shoulder bag and free-swinging pageboy haircut. In their place were a Jackie Kennedy-style pillbox hat, a shapeless canary-yellow jacket, and a skirt that reached almost to mid-calf.

All the questions had been submitted to the couple in advance, and none of the Japanese reporters had the nerve to ask whether Masako had negotiated some kind of deal. A hint that she had done just that came when she went out of her way to inform the national television audience that the prince himself had assured her, "Masako-san, I will protect you for my entire life." Though she pointedly did not say exactly from what the prince was going to protect her, everyone understood that she was talking about the Imperial Household Agency. She was not someone to be pushed around. "I would be lying," she said, "if I said I had no sad feelings about leaving the foreign ministry, but I felt that my role now was to accept the proposal from the prince and make myself useful in my new life in the imperial household."

It was a graceful performance by a mature young woman who had made the compromise of her life. Clearly, Masako Owada was no Lady Diana Spencer, a perennial adolescent who would someday throw a spanner into the imperial works. She turned up at her formal engagement ceremony looking like a porcelain doll, with her hair swept up and her body cinched into a flowered kimono. Like the royal wedding ceremony itself, which, despite its ancient trappings, was invented from scratch in 19th-century Meiji Japan, Masako was a powerful symbol, if not exactly the politically correct symbol everyone would have liked to believe she was.

Indeed, the choice of Masako—a woman who had once confessed that she felt as much American as Japanese— had to be seen as part of a turning point in her country's postwar history. During my trip, I found the Japanese deeply concerned about the prospects of dealing with the commercial hawks in the Clinton administration, and of being frozen out of the European and North American trading blocs. Some of these fears are a result of the usual Japanese victim mentality. But most are well-founded, since the Japanese know that they can't go on having lopsided economic relations with every other country while refusing to behave like a responsible great power. In short, the Japanese have reason to believe that the world has lost patience with them.

"This wedding doesn't mean anything about the status of women in Japan, " said Professor Helen Hardacre, a Harvard specialist in Shinto, Japan's indigenous religion. "It will be used as proof of Japan's internal reforms and outward internationalization, while the fundamental facts of life in Japan remain unchanged or are even going backwards.

"Right now," she continued, "Japan is going through an economic crisis. For the first time, big corporations are laying people off. This is a frightening portent for the future. Japan is being forced to change and to open up—to goods, to ideas, even to people. With her special background, Masako will be a crown princess who will help the crown prince communicate with the West as equals, so that the Japanese don't have to feel that their ethnicity or identity is threatened by interaction with the outside world."

During his courtship of Masako, Naruhito confided that he had been aware from childhood of his destiny. He knew that someday, as emperor, he would become the living symbol of his countrymen's sense of shared identity and their belief in themselves as a kishu, or noble species. In a very profound sense, he and the woman who married him would have in their joint custody the entire nation's self-esteem.

His major male role model as he was growing up had not been his father, Emperor Akihito, a pleasant but somewhat aloof character. It had been his grandfather Hirohito, the wartime emperor, whom Naruhito idolized. To the crown prince, Hirohito was neither the belligerent figure on a white horse pictured in newsreels of the 1930s and 40s, nor the doddering old myopic marine biologist of his latter days. He was a man of stoicism and purity.

"Naruhito learned that after Hirohito got married he had three daughters in a row and no sons," said Takao Toshikawa, a well-known Japanese journalist. "Many of Hirohito's aides urged him to take a concubine so that he could have a son and heir, but Hirohito rejected such advice. Eventually, of course, he had two sons, one of whom was Naruhito's father, but it was Hirohito's strict morality that appealed to Naruhito."

The moral strain in Naruhito's character could be traced to the influence of his mother, Empress Michiko. Many palace sources believe that Michiko has lived as a crypto-Roman Catholic sympathizer during her entire time in the imperial household, despite the fact that her husband is the chief shaman-priest of Shinto. Naruhito was the first crown prince in Japanese history who was not taken away from his mother in infancy and raised by wet nurses and chamberlains. Michiko insisted that she be allowed to breast-feed him, which she did until he was weaned at 11 months. Whenever Michiko went off on royal business, she instructed her ladies-in-waiting to play Naruhito tape recordings she had made of herself singing lullabies. Not surprisingly, her son developed what Japanese psychologists call "skinship," or extreme closeness.

Japanese society may appear to outsiders to be a patriarchy, but some experts would argue that it is, in fact, made up of equal parts public patriarchy and private matriarchy. In their homes, Japanese children are influenced far more by their doting mothers than by their fathers, who are absent most of the time. Boys in particular are subject to enormous affectionate influence from their mothers, and in this respect Naruhito was no different from commoners. To this day, the competitive empress never passes a tennis court on which Naruhito is playing without calling out, "Are you winning? You're not losing, are you?" As a result, Naruhito has developed a character very much like Michiko's—serious, stubborn, and determined to win at all costs. To many of the young women who were mentioned as possible candidates for crown princess, Naruhito came across as a boring ojin, colloquial Japanese for "old daddy."

Masako was too old, too tall, and, in the eyes of the Imperial Household Agency, far too "Americanized."

Naruhito may have cultivated this image to distinguish himself from Prince Akishino, his haughty, headstrong younger brother, whose nickname is Fast Hands, because of his reputation as a heavy drinker and womanizer in Tokyo's nightclubs and discos. Though the facts have never been published in Japan, it is widely believed that Akishino's intimate relationship with his steady girlfriend, Kiko, became a matter of serious concern to the court. Eventually, as a result of pressure from Kiko's father, the Imperial Household Agency had no choice but to allow Akishino to marry in the summer of 1990, even though tradition dictated that the younger brother wait until after the crown prince was wed.

The brothers' relationship is marked by sharp sibling rivalry, at least on the part of Akishino. Knowing how sensitive Naruhito is about his height (he claims to be five feet five) and his eyes (which have epicanthic folds), Akishino once reportedly told him, "The reason you're having trouble finding a wife is that you're not the girls' cup of tea. You're too short-legged and too Mongolian-looking."

The head of a chain of supermarkets, who taught kendo, a traditional form of Japanese fencing, to both Naruhito and Akishino, reportedly remarked that while the crown prince was a diligent student, his younger brother was incapable of absorbing the spiritual values that are at the heart of all martial arts.

Nobutoshi Koma, one of the crown prince's classmates at Gakushuin, the former peers' school in Tokyo, said he was convinced that Naruhito's female ideal was strongly patterned after the image of his mother. "His respect for and gratitude toward his mother are two pretty deep feelings in the prince," Koma reportedly observed.

Upon his graduation in the early 1980s, Naruhito was sent to Oxford University, where he studied 18th-century British waterways. He lived in a dorm under the watchful gaze of a court chamberlain and a pair of burly Scotland Yard bodyguards. During his absence from Japan, Minoru Hamao, a retired chamberlain, confidently predicted to Japanese reporters, "Various studies of candidates for the prince's bride have been carried on quietly for the past two or three years. It would therefore be normal for his engagement to be announced when he returns to Japan next year." That was in 1984.

By last year, Empress Michiko and Emperor Akihito were so concerned over their son's inability to find a bride that they called in Shoichi Fujimori, the plumpish director of the Imperial Household Agency, and asked him to form a crisis-management team. "The royal couple vehemently denied that they had any involvement in this affair, because they wanted it to look as though the prince was acting on his own," said an old friend of the emperor. "They didn't want the appearance of an o-miai kekkon, an arranged marriage. They wanted it to appear like a love marriage, which would be an example to the young generation of Japanese to think for themselves."

Up to that point, the Imperial Household Agency had adhered to a set of inflexible standards for judging the prospective bride: She had to come from a family with impeccable credentials going back three generations. She had to be in her early 20s and shorter than the prince. She should speak a foreign language. Pierced ears, eye operations, or any other physical mutilation would rule her out. And she had to be a virgin.

The trouble was, virgins weren't exactly lining up outside the palace to marry the prince. In fact, several women identified by the press as hot prospects arranged hasty miyasama-yoke marriages, or marriages to forestall a royal proposal.

There were a number of reasons for this. One was pure physical fear; a yes to the prince would immediately make the future bride and her family targets of Japan's leftwing terrorist groups.

There was also the fear of falling victim to the Michiko syndrome; most modern young women had no interest in subjecting themselves to the restrictions and constraints that are the essence of Japanese court life.

A woman marrying the prince, wrote Takie Sugiyama Lebra, author of Above the Clouds, a study of the Japanese nobility, "would be doomed to virtual slavery to palace tradition and continual surveillance by the 'nasty' nyokan [female attendants], as well as to the curious eyes of the entire nation. A status barrier between her and her natal family would be created to inhibit their reunion.''

Yet another reason was the sheer economic burden. "Royal marriage," noted Lebra, "would require that the bridal family not only pay an enormous dowry and wedding expenses but also constantly present gifts to the whole royal household, from its head down to its lowest servants. In addition, they would have to maintain a life-style appropriate to a royal [relative by marriage] and satisfy social obligations, again including gift giving, within the kin network of royalty and its circle."

"Unless you pleased all of them down to chauffeurs with generous gifts," said one of Lebra's informants, whose daughter married into royalty, "they would give your daughter a hard time." Indeed, the crushing financial burden reportedly drove Viscount Takagi, the father-in-law of Naruhito's great-uncle, Prince Mikasa, to commit suicide.

Frustrated at every turn, Shoichi Fujimori flipped through his old computer printouts and came upon the name of Masako Owada. A favorite of the crown prince's, Masako might be worth another look.

As a youngster, Masako had been a tomboy with a passion for snakes and baseball. She still liked sports, and she owned a dog named Chocolat. She displayed a streak of healthy independence, and traveled on her own to Hawaii, where she swam and sunbathed in sexy bathing suits. She was now working in a division of the foreign ministry that handled thorny trade negotiations with the United States. She had lived for many years in America, spoke English as fluently as she spoke Japanese, and had once served as an interpreter during talks between Secretary of State James Baker and his Japanese counterpart, Michio Watanabe.

The anti-Masako stories reinforced the stereotype of America as a sex-crazed country that contaminated Japanese who lived there.

Her father, a highly respected diplomat with a thatch of silver hair, was the senior professional officer at the foreign ministry, and was being groomed as a future ambassador to Washington, or perhaps to the United Nations. There was only one problem with her family: Masako's wealthy grandfather had been the chairman of the Chisso Corporation, a chemical company responsible for a major pollution scandal. In the late 1950s, Chisso had dumped mercury into the waters around the town of Minamata, causing severe birth defects and other health problems. However, Masako's grandfather hadn't joined the company until after the disaster took place, and so as far as Fujimori was concerned, he could hardly be held responsible for the disaster.

Nonetheless, Masako had a number of strikes against her. She was too old, too tall, and, in the eyes of many conservative members of the Imperial Household Agency, far too "Americanized" —a phrase that in context suggested morally loose.

According to one insider, her name had been eliminated years before, after an undercover team of Japanese investigators traveled to the United States to look into her personal behavior during the time she attended public high school in Belmont, Massachusetts, and college at Harvard. After the investigators returned to Japan, all sorts of rumors started making the rounds. People gossiped wildly about the existence of a letter alleging that Masako had had love affairs. According to one story, a Chinese-American student in America claimed that he had had an affair with her at Harvard, and that he had a set of photographs of her nude for sale. Another story charged that a former foreign boyfriend (it was not clear if he was the same Chinese-American or someone else) had moved to Tokyo to be near her, and was working in an American brokerage firm. A third tale had her carrying on an affair with a man in her division of the foreign ministry.

No one, however, came forth with any evidence. And it appeared that the whispering campaign had been fomented, at least in part, by competitors of Masako's father. In addition, former aristocrats didn't want to see another commoner marry into the royal family. What the anti-Masako stories did do was reinforce the stereotype of America as a sex-crazed country that contaminated Japanese who lived there for any length of time. Since her opponents in the Imperial Household Agency would not come right out and voice their suspicions, her grandfather's "Chisso problem" was used as a convenient excuse to veto her candidacy.

Masako was furious. At one point, she confided to a former Harvard classmate, "I cannot tolerate the idea of sacrificing my freedom. I could never accept such a life." She even went on television and stated in as public a manner as possible that she had absolutely no interest in marrying the prince.

It was at this point that the desperate Fujimori came up with a masterstroke. He reached out for help from Kensuke Yanagiya, a retired diplomat who had once been Masako's father's superior in the foreign ministry, and who had helped in advancing Owada's career. By Japanese, standards, Masako's father owed immeasurable giri, or moral debt, to Yanagiya, so when the old man paid repeated visits to the Owada home and talked about the crisis looming over the imperial institution, he had to be listened to. ''If my daughter is wanted," Masako's father eventually conceded, ''she should be married to the prince."

Yanagiya then arranged a series of secret meetings of the prince and Masako, first at his own home, then at the imperial duck-hunting grounds on the Chiba peninsula, outside Tokyo. The prince gave it his best shot. ''If you become a diplomat or my wife, either way you serve to promote better understanding for foreign countries," he told Masako. But his best was not good enough, and the six-hour meeting on a cold and blustery day last October turned out to be a flop. "I cannot promise I will not turn down your proposal," Masako replied. And 17 days later, she sent word through a third party that enough was enough and she was not willing to marry the prince.

By then, however, it was only a matter of time before Masako would cave in to all the pressure. And in mid-December, after her fateful tête-à-tête with the empress, Masako's resistance finally collapsed, and she told the prince that she would be his bride.

She sat down at home and wrote her parents a pathetic little Christmas card: "Dear Father and Mother. . .Sorry for making you worry so much about me this year. But with your support, I was able to think it out and take the right step toward a new life. This Christmas and year-end may be the last we'll be able to spend together. I really appreciate it that you raised me all these years in such a warm and happy family. Tough times are waiting for us, but I hope we get through."

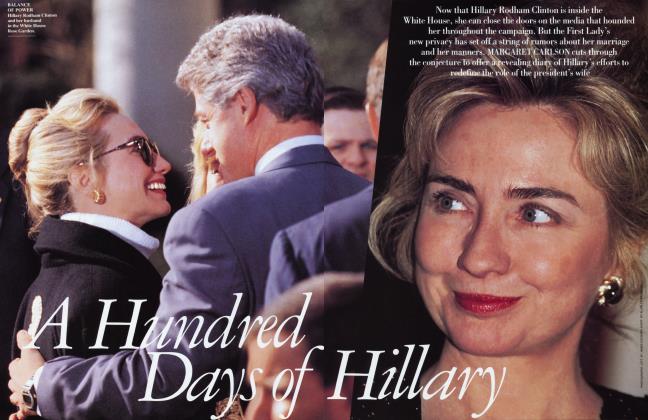

And tough times are sure to come— both for Masako and for Japan. Many people who followed this imperial drama predicted that, given the new crown princess's background and character, she would dominate her husband and fundamentally change things inside the palace. "She's Japan's Hillary Clinton" was a phrase I heard quite often. The obvious implication is that Masako is some sort of willful woman who is determined to get her way or else. But the Japanese like to avoid open conflict at all costs, and it is far more likely that Masako will play her new role for all it is worth, thereby strengthening, rather than weakening, the monarchy.

"She's Japan's Hillary Clinton" was a phrase I heard quite often.

During my stay in Japan, there was a great deal of talk about how the long and arduous search for the crown princess had turned out for the best, because Masako Owada and Crown Prince Naruhito will make the perfect ambassadors of goodwill. People could imagine this cosmopolitan pair traipsing around the world in their jet planes and designer suits and dresses, enhancing the image of Japan as a modem, postindustrial country.

Little, however, was said about the other function of the imperial institution, the one that takes place in the secret recesses of the Shinto shrines in the Imperial Palace, with everyone outfitted in ancient court costumes. Yet it is a fact that the very modern Masako will end up spending much more of her time bowing in ceremonies than standing on her own two feet in foreign capitals.

Numerous Shinto rituals are performed each month by the emperor and the crown prince, often with their wives in attendance. Shinto was disestablished as a state religion after World War II, and these ceremonies are now technically conducted as the personal religion of the emperor and his family. But although most Japanese profess to pay no attention to the rituals, they are key to understanding what is going on in today's Japan.

"The presence of Shinto rites in the palace serves to enhance the imperial institution's symbolic role as quintessentially and unquestionably Japanese," David A. Titus, a professor of government at Wesleyan University, told me. "The emperor's involvement in and approval of relations with the world makes those relations acceptable to Japan. The imperial institution facilitates Japan's internationalization by putting the imprimatur of this most Japanese of Japanese institutions on the absorption and acceptance of the world's cultural and material resources. It provides an important psychological. . . vehicle for the internationalization of the Japanese, by the Japanese, and for the Japanese."

Japan is in the midst of a great debate about "a second opening," perhaps not as traumatic as the one forced by the appearance of Admiral Perry's black ships in Tokyo Bay in the 1850s, but nonetheless extremely important. Masako is the second commoner in a generation to become princess-to-be. There is already a serious movement in Japan to scrap the American-written constitution, with its clause preventing Japan from sending offensive-combat troops abroad. And when the constitutional Pandora's box is opened, the role of the emperor will come under fresh scrutiny. Inevitably, there will be those who will want to increase the importance of the imperial system as a way for Japan to sustain its cultural purity and ward off Western contamination.

"I'm afraid there will be a strong reaction to this opening of Japanese society," Yoshikazu Sakamoto, a left-leaning scholar at Meiji Gakuin University, told me. "As in Germany, there is a great danger of a resurgence of ethnocentrism in Japan. Royalists will become more royal than the emperor, and try to use the imperial family for their nationalistic purposes. If things get worse economically, people will resort to myth and resurgent nationalism. I can foresee a serious split in society."

Emperor Akihito is only 59 years old, and may sit on the Chrysanthemum Throne for another two decades or more. But eventually Naruhito will ascend the throne, and Masako will become the empress. And these two will help guide Japan in the 21st century, which, after all, is likely to be the Japanese century.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now