Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

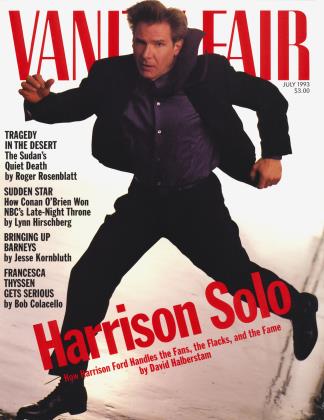

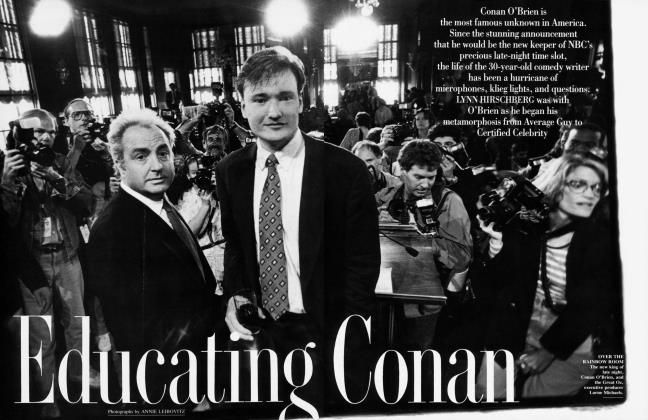

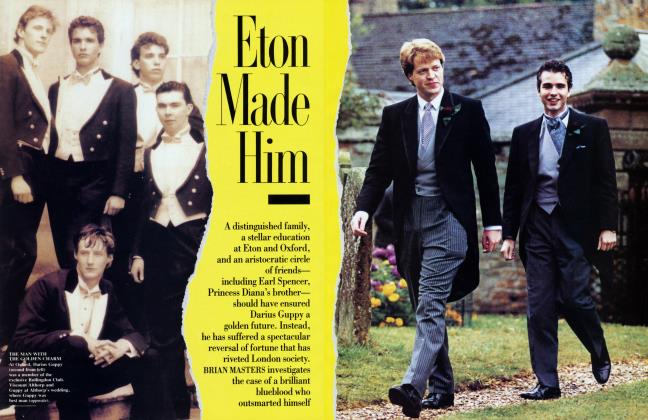

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowROYAL WITH A CAUSE

BOB COLACELLO

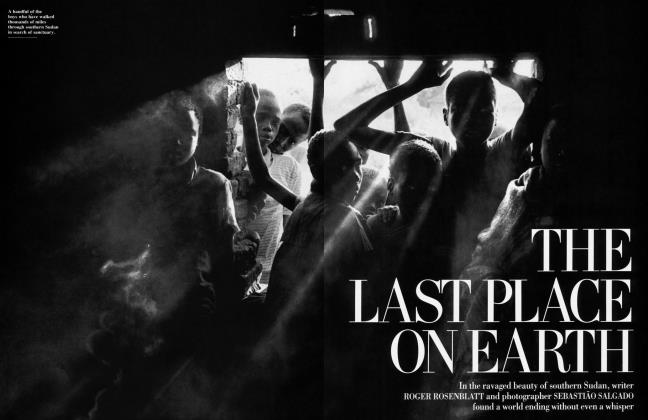

When Francesca Thyssen, the Concorde-set party girl, married Karl von Habsburg, heir to Europe's exalted dynasty, she sealed their status as the Continent's newest power couple. She has created a foundation to save endangered works of art, while he runs medical supplies to the battlefields of the former Yugoslavia. Reporting from Austria, Switzerland, and Croatia, BOB COLACELLO finds a royal flush of great art, Balkan politics, and social intrigue

"Deep down under all that frantic going-out-all-night sore of thing she had this goodness to her"

his month, the Villa Favorita, Baron Hans Heinrich ThyssenBomemisza's private museum and occasional residence on Lake Lugano in the Italian-speaking part of Switzerland, opens its

first major exhibition since the cream of the baron's collection was shipped off to Madrid two years ago, in what may turn out to be the biggest and most controversial deal in art history. It is also the first exhibition organized by the baron's only daughter, Francesca, a 35year-old former model and reformed party girl who earlier this year rocked European royalty by marrying Archduke Karl von Habsburg, a 32-year-old conservative activist and the heir to the throne of the long-defunct Austro-Hungarian Empire, in the most talked-about Mittel-European wedding since that of Gloria and Johannes von Thurn und Taxis in 1980.

The exhibition features 70 extremely rare and highly important 11thto 13thcentury Buddhist paintings from a lost Silk Road civilization which have never before been shown as a group outside the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg. It is one part of the new archduchess's impressive program to maintain the Villa Favorita as the cultural focal point of Lugano and the surrounding Ticino Canton. Two years ago, she established the Art Restoration for Cultural Heritage Foundation, known as ARCH, on the grounds of the villa, and she is hoping to organize future exhibitions of newly available artworks from Eastern and Central Europe. "What triggers me is the repression of cultural and spiritual heritage by Communist governments, whether it be in the former Yugoslavia or Tibet,'' she says. "Eastern European museums are packed full of great things which are deteriorating very fast, and they don't know what to do with them. That's why I see the Villa Favorita becoming a window to Eastern Europe. I think it's important to do these things. You have to stand up."

If Archduchess Francesca von Habsburg's grand plan succeeds, she will undoubtedly become, along with her politically ambitious husband, a leader of Europe's highest social, cultural, and governmental circles.

"I think Francesca has it in her to reanimate the villa," says Simon de Pury, deputy chairman of Sotheby's and the former director of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, although he thinks it will be difficult to overcome the loss of the superior half of Baron Thyssen's collection of some 1,500 artworks, including masterpieces by Holbein, Diirer, Ghirlandaio, Caravaggio, van Gogh, and Picasso. These works are on loan to the Spanish state for nine and a half years for an annual fee of $5 million, and tense negotiations are in progress to sell them to Spain for about $400 million.

This past April, the redecorated Villa Favorita reopened its 17th-century carvedoak doors to the paying public. The gallery walls had been stripped of their darkbrown velvet, painted light gray, and hung with about 150 of the works remaining in Switzerland, mostly 19thand 20th-century European and American paintings and watercolors by an assortment of artists that included Maxfield Parrish and Alfonso Ossorio as well as Max Ernst and Jackson Pollock. ("The leftovers," said one family friend. "Some of which were hanging in guest rooms of the baron's various houses and never meant to be shown in a museum setting. ")

Baron Thyssen, who is 72 and known as Heini, and his fifth wife, Carmen Cervera, known as Tita, a onetime Miss Spain widely held to be most responsible for his collection's going to her country—despite personal appeals from Prince Charles and Helmut Kohl on behalf of their countries—were expected in Lugano for the reopening. But at the last moment they decided to stay in Madrid, because the death of the father of King Juan Carlos was thought to be imminent and they didn't want to risk missing the funeral. (Don Juan de Borbon died that evening.)

"In a way, this marriage was a gift to her father̶she gave Heini a Habsburg."

Maybe the Habsburgs were just the kind of family

In the event, the day belonged to Francesca. Three years ago, when she realized that her father, encouraged by her Spanish stepmother, was seriously thinking of selling the Villa Favorita (for a rumored $30 million, according to Forbes), Francesca reacted with a stubborn fury. She had lived at the villa until she was seven, when her father split up with her mother, Fiona Campbell-Walter, the legendary Scottish beauty who was his third wife, and she was determined to keep it in the Thyssen family. (The baron's father, an heir to the immense Thyssen steel-and-iron fortune, had bought it in 1932 from Prince Friedrich Leopold of Prussia.) Putting aside the aimless life she had been leading in London since the late 70s, she moved back to Lugano and was appointed curator of special events by her father and the board of the Swiss foundation that runs the villa, on which she has a seat.

Now, though she played down talk of a "new regime" and emphasized her father's "keen interest in the continuing activities at the villa," she was clearly in charge and obviously enjoying it. On the morning of the reopening, she calmly presided over a packed press conference. That afternoon, she delivered a well-received speech at a cocktail reception attended by the local officials and bankers she has been wooing to help support the villa, reminding them of its longtime international appeal to affluent tourists. That evening, she hosted a casual dinner in a homey trattoria for about 50 friends who had driven up from Milan or down from Zurich and Geneva. It was an art-world blend of collectors, curators, architects, and writers, but it also included a Tibetan professor from Cologne who brought her blessings from the Dalai Lama, who had originally suggested that she do the Buddhist exhibition, and the young Jesuit priest who had directed her conversion to Catholicism so that she could marry into the Habsburgs and bear the title Archduchess of Austria. (Not invited for dinner, though he was at the cocktail party: Fred Horowitz, the Geneva jeweler who introduced Tita to Thyssen 12 years ago, and from whom the baron has since bought numerous baubles costing numerous millions for the baroness, including the biggest cut diamond in the world.)

Although Francesca's closets are stuffed with Versaces, Lacroixs, Montanas, and Pradas, she wore the same outfit from morning to midnight: an Austrian-style green loden jacket with a high black velvet collar and a matching below-the-knee skirt—the slightly dowdy royal look. Her long Titian hair was neatly combed with a part on one side, and if she was wearing any makeup, it was not noticeable. "Karl doesn't like me to look fashiony," she told me at dinner, beaming a confident smile at her husband. Yet her confidence had disappeared in a flash earlier in the day, after her father called from Madrid. "Daddy's not coming," she announced in a strained, little girl's voice.

"It's incredible how much Francesca wants her father's approval," a woman who has known her since childhood says. "Her whole aim in life is to please her father. In a way, this marriage was a gift to him—she gave Heini a Habsburg."

Although the marriage may have pleased her father, it infuriated her stepmother, according to one of Baroness Tita Thyssen's oldest friends, who repeated the worst-kept secret of the Spanish court: by persuading her husband to choose Spain as the home for his collection, Tita, whose previous husbands were Lex Barker, the late star of several Tarzan movies, and Espartaco Santoni, a Spanish-Venezuelan movie producer and nightclub owner, and who has an illegitimate teenage son by an unnamed father, hoped to be made a duchess by King Juan Carlos. Not only has that not happened—and according to the king's biographer, Jose Luis de Vilallonga, it never will happen—but two weeks prior to the grand opening of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection at the old Villahermosa Palace, opposite the Prado Museum in Madrid, last October, an event which Tita had been planning for months, her stepdaughter stole the limelight with the formal announcement of her engagement to the scion of the family that once reigned in Spain as well as in Austria. "Francesca and her Habsburg archduke upstaged Tita at every party in Madrid," said the baroness's old friend. And, as one title-worshiping socialite put it, the would-be duchess "now has to curtsy" to the archduchess.

Complicating family relations further is the fact that the agreement to keep the collection in Spain permanently cannot be finalized without the signatures of Francesca and her three grown brothers: Georg-Heinrich, 41, the baron's son by his first wife, the German princess Teresa of Lippe, who runs his father's business; Lome, 30, the other child by Francesca's mother, Fiona Campbell-Walter; and Alexander, 18, whose mother is the baron's fourth wife, Brazilian soft-drink heiress Denise Shorto. The children's power derives from a family contract they signed around the time of Thyssen's 1985 marriage to Tita, who also signed it, in which all his heirs renounced their claims to the core of the collection with the intention that it remain intact at the Villa Favorita. In February of this year, Tita reportedly told a journalist that if the Spanish deal wasn't sealed within 45 days "heads will roll." Oddly, that deadline coincided to the day with the April reopening of the Villa Favorita, and the children had not yet signed.

Was that the real reason the baron and baroness stayed away?

A few days later, I posed the question to Francesca von Habsburg in her suite at the Palace Hotel, in Zagreb, Croatia, where she was beginning a one-week fact-finding trip for her ARCH Foundation. She admitted that she would have preferred that the collection stay in Lugano, and that when it left for Spain she was "terribly upset—it just emotionally gutted me." But, she continued, "if that's not to be, and if the reality now is what my father profoundly wishes. . .it is his collection. The argument that he did inherit a great big part of it [from his father]—and why shouldn't we also inherit a great big part of it—is just not discussable. What's his is his. And if he chooses [to sell it to Spain], whether or not it's under constant pressure from Tita, I'm much less critical than I used to feel. I think if you look at it for what it is and you don't compare it to what it was, one cannot say it's a bad deal. As you know, my stepmother was totally instrumental to this thing working, and I see now that she participated in a great achievement."

this worldly heiress needed.

She added that attending the opening of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, which the Spanish government had spent $45 million refurbishing for the collection, helped change her mind. "The museum is absolutely stunning, I have to say. I totally object, like several other people do, to the wall color, which is salmon pink. It's appropriate for some groups of paintings, but not for all of them, and it gets rather tiring by the time you hit the 27th room." She didn't mention the widely reported fact that her stepmother had insisted on pink walls and white marble floors.

Our interview was interrupted by the arrival of Karl von Habsburg and his mother, Archduchess Regina von Habsburg, a tall, straight-backed woman in her late 60s, who was bom a royal princess of Saxony. She had come to Zagreb to accompany her son and daughter-inlaw down the Croatian coast to the walled medieval city of Dubrovnik and then to take them on her annual Easter-time pilgrimage to Medugorje, the small town in Bosnia where the Virgin was said to have appeared to a group of children in 1981. Karl's father, Archduke Otto von Habsburg, 80, the son of the last Austro-Hungarian emperor, Charles I, and a member of the European Parliament in Strasbourg, had planned to make the trip with them, but he had to be in Madrid for the funeral of his cousin Don Juan de Borbon. (He was seated in the fifth pew with other European royalty; Baron and Baroness Thyssen were several pews back with the foreign diplomatic corps.)

Set in a series of historical villages in the Austrian Alps this past January, the wedding of Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza to Karl von Habsburg was a weekend swirl of champagne and schnapps, silvered saints and emerald necklaces, imperial flags and provincial militias, falling snow and raging rumors: That the bride was expecting. ("If what the press speculated was true, I should have been eight and a half months pregnant on my wedding day," says Francesca.) That the bride's father paid the groom's father several million dollars to approve the marriage. ("I didn't pay them anything.

I paid for the wedding, but normally the father of the bride has to pay.

Maybe it was a little bit extravagant. Well, I only have one daughter," says Baron Thyssen.)

That the groom's imperial relations boycotted the wedding en masse.

("There are 700 Habsburgs. Half didn't come and half weren't invited," says a houseguest of a Habsburg who declined the invitation, as did Otto von Habsburg's four younger brothers, in revenge, the aristocratic set whispered, for his refusal, as head of the House of Habsburg, to allow some of their children to marry below their rank without losing their royal status.)

Still, there were enough exotic titles to go around the 68 tables at the black-tie dinner the bride's parents gave in the medieval monastery in Gaming the night before the wedding, including Dom Duarte of Portugal, Queen Anne of Romania, Crown Prince Asfa Wossen of Ethiopia, Prince Victor Emmanuel of Savoy, Prince Nicholas Dadechkeliani of Georgia, Princess Yasmin Aga Khan, Princess Gloria von Thurn und Taxis, Prince and Princess Ernst von Hannover, Prince and Princess Heinrich von Furstenberg, Count and Countess Brandino Brandolini, the Duke of San Carlos, and the Duke of Argyll, head of the Campbell clan. The King of Morocco sent his daughter, Princess Lalla Hasna, to represent him, and is said to have sent a car as a wedding present.

The next morning the three-hour High Mass in the Baroque basilica of Mariazell juxtaposed Roman Catholic ritual with

jet-set glamour. As the Cardinal of Vienna and the Bishop of Zagreb, assisted by nearly a dozen priests and as many altar boys, intoned in Latin, German, English, Italian, Hungarian, and Croatian, Anne Bass held back tears, Nan Kempner struggled with her deconstructing Fendi fur coat, Lynn Wyatt waved across the aisle at Mick Flick, Sao Schlumberger knelt in prayer, and Claus von Biilow stood in line for Communion. Tita (Continued on page 130) (Continued from page 107) Thyssen wore black to church, and Heini Thyssen stunned everyone by turning up in a Hungarian hussar's uniform that he said was 100 years old, a reminder of his own aristocratic roots: his German father married a daughter of the Hungarian Baron Bomemisza and had himself adopted by his mother-in-law so that he could use the Bomemisza title and pass it on to his descendants. This maneuver, by the way, required a special decree from Emperor Franz Josef, the brother of Karl von Habsburg's great-great-grandfather.

The Habsburgs, of course, trace their noble lineage back to the 10th century. They are both imperial and royal highnesses, and their firstborn sons—including Karl, theoretically—inherit more than 40 titles, including Emperor of Austria, Apostolic King of Hungary, King of Jerusalem, King of Bohemia, King of Dalmatia, King of Transylvania, King of Croatia and Slovenia, King of Galicia and Illyria, Grand Duke of Tuscany, Margrave of Moravia, Duke of Salzburg, and Duke of Modena. Even among the royal families of Europe, the Habsburgs are considered particularly conservative, strict, devout, and alert to the possibility—however remote—of their restoration to power. They are also known for their morbid streak, which can be seen in the elaborate funeral customs they have followed for centuries, right up to the burial of Karl's grandmother Empress Zita four years ago. Habsburg hearts are removed from their corpses, mummified, and buried in a crypt in St. Augustine's Church in Vienna; their other innards are removed, mummified, and buried under the high altar of St. Stephen's Cathedral, also in Vienna; the remains of their remains are embalmed and put to rest in the family pantheon beneath Vienna's Church of the Capuchins. It was in this airless underground tomb, surrounded by 138 of his ancestors' lead-colored coffins, many of them encrusted with ornate crucifixes and crowned memento mori, that Karl asked Francesca to marry him.

"This is where you will lie someday," he is said to have told her.

"Is that a proposal?" she replied.

He said yes without hesitation, and so did she.

Maybe the Habsburgs were just the kind of family this worldly heiress needed.

When her parents divorced in 1964, Francesca says, "I was shuffled off to boarding schools." On holidays, she visited her mother in Saint-Moritz or her father at the Villa Favorita, if her Brazilian stepmother invited her. In the 70s, both households were touched by scandal and tragedy. Francesca's mother, Fiona, was involved in a tumultuous relationship with a much younger man, Alexander Onassis, the son of the Greek shipping tycoon; they had finally decided to live together, despite Ari Onassis's disapproval, when Alexander died in a mysterious plane crash. Francesca's stepmother, Denise, was having an affair with her husband's art dealer, Franco Rappetti—until Rappetti jumped or was pushed from a Manhattan apartment-building window in 1978, and was replaced as the baron's leading art dealer by the notorious Andrew Crispo.

As one title-worshiping socialite put it, the would-be duchess "now has to curtsy" to the archduchess.

That same year, after graduating from Le Rosey in Gstaad, Francesca enrolled at St. Martin's School of Art and Design in London. "It was the school where the Sex Pistols had their first concert, so the whole place was bursting with this new expression of punk and we were right bang in the middle of it. I went, 'Yeah, this is great.' I was very angry. I was a very, very angry teenager. I was very, very hurt about being sent off to all these schools, and I just developed a lot of anger over the years. And it expressed itself in the punk movement. I mean, off came the hair and in went the safety pins."

She tried to be an artist, a model, a photographer, an actress, and an art dealer, but became best known as a hostess and confidante to stars in those fields, including Robert Mapplethorpe, Francesco Clemente, Sandro Chia, and Enzo Cucchi. One of her best friends was New Wave singer Steve Strange, who also ran the Camden Palace, the Studio 54 of London, where she often made late-night entrances in Vivienne Westwood numbers on the arm of Boy George. Her only serious romantic relationship, which lasted six years, was with Wayne Eagling, a principal dancer with the Royal Ballet, who is now the artistic director of the Dutch National Ballet.

She lived in a mews house that her father owned on Seymour Walk, off the fashionable Fulham Road. "I was her next-door neighbor for a year in the early 80s, and we became close friends," says writer James Fox. "So I saw all sorts of activities, all quite frantic and exciting, mostly very late at night or very early in the morning. I thought that deep down under all that frantic going-out-all-night sort of thing she had this goodness to her. She was very generous, always doing things for people, arranging things for them. But she was also frustrated that she wasn't doing anything, really. It's not that she lacked energy; she was tremendously driven. She used this phrase, 'I'm running late,' a lot. As if she had this schedule, you know, she had to keep. It was rather funny and touching."

Robert Mapplethorpe also saw something deeper in Francesca. At the height of her punk period, he did a pair of portraits of her looking like an ethereal Renaissance infanta. "Robert saw through people completely," she said. "That's why I liked him. The second time I met him, he said, 'Can you just drop the act?' And I said, 'I'm not acting.' He said, 'Yes, you are, and knock it off. You're a nice person. I like you. You don't have to do this crap.' He was the first person who ever said that to me."

In 1989 she met the Dalai Lama—and found a career. Her father, she explained, had made a substantial donation to help build a Tibetan cultural center in Dharamsala, India, the Dalai Lama's capital in exile, and was invited to meet the Buddhist spiritual leader in London. "His Holiness always likes to thank his big donors personally," she said. "I just tagged along. My father was talking about what else he could do, and that's when the idea of an exhibition came up."

The exhibition—"Khara Khoto: Treasures of the Buddhist Civilization of the Tangut Kingdom, Between China and Tibet"—required more than three years of negotiations, research, and hard work. It finally gave her the focus she had always lacked, as well as a real role at the Villa Favorita. She made a long trip to the backward Buryat republic in Siberia, near the Mongolian border, to document the desert site of the lost city of Khara Khoto, which was sacked by Genghis Khan in 1227. She accompanied the Dalai Lama to St. Petersburg and persuaded officials at the Hermitage, where the Khara Khoto collection forms the nucleus of the Oriental department, to lend a group of the major paintings for the first time since they were unearthed by the Russian Imperial Geographic Society at the turn of this century. She also went to Tibet. "She wrote wonderful diaries from Tibet, parts of which she showed me," says her English friend Lady Anne Lambton. "I think Tibet changed her."

In 1991 she set up the ARCH Foundation in a two-room office next to the villa. She subsequently hired the distinguished cultural fund-raiser Dr. Eric-Christian Verhaagen Henriksen as its secretary-general and put together an impressive board, including J. Carter Brown, the former director of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.; Dr. Paolo Viti, the director of the Palazzo Grassi in Venice; and Dr. Marilyn Perry, the chairman of the World Monuments Fund. Perry is also the president of the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, which has given ARCH a $50,000 grant to design mobile conservation laboratories—"first-aid vans for art," Francesca calls them. Her initial interest centered on St. Petersburg and Hungary, but then war broke out in Croatia.

ARCH was barraged with faxes from beleaguered Croatian cultural officials, begging for help in saving endangered artworks. In November, Francesca decided to investigate the situation firsthand. A mutual friend suggested contacting Karl von Habsburg, who was making frequent trips from Salzburg to embattled Croatian cities such as Vukovar and Osijek to deliver medical supplies, warm clothes, sleeping bags, and baby food. He told her that he was leaving on another trip the next morning and offered to take her along, although, she says, "he thought I was a bit crazy."

Nick Danziger, a war photographer whom she had helped get a job recording the cultural damage in Croatia, says, "We left Lugano about 11 or 12 that evening, drove right through the night, got to Salzburg in time for breakfast at 6 or 7 in the morning, and immediately left for Zagreb." At first they followed Karl's Volkswagen in Francesca's BMW sport convertible, but at the border they left her car and got into his.

"I think Karl and I were very curious about each other, about why we both felt so strongly about certain things," Francesca told me. "And I discovered very quickly that he felt very strongly about things because he knew an awful lot about them, and I felt very strongly about things because I knew nothing about them. And I was going to find out pretty fast if I stuck around Karl."

They spent five days in Croatia, based in Zagreb, the relatively peaceful capital. Francesca met with the minister of culture and education, came close to the fighting on the front line in the beautiful Baroque city of Karlovac, and found herself without an answer when local TV and radio reporters demanded, "What are you going to do about this?"

Within a month, she organized a conference in Zagreb on the subject of saving Croatia's cultural heritage. It was attended

In 1989 she met the Dalai Lama— and found a career. "That's when the idea of an exhibition came up."

by more than 200 scholars, curators, conservators, and journalists from several European countries and began to bring international attention to the severity of the crisis. "I was way out of my league, ' ' Francesca said. "If I'd known how to do a conference, I probably wouldn't have attempted it. But Karl was there for me. He would take me aside, slip me little notes, tell me, 'Now you have to thank these people,' 'Remember to introduce those people,' 'Why don't you come into this room and start working on your plenary session?' And I thought, Wow, this guy is looking after me in the kindest and most generous way. I've never had that feeling from any of the men in my life, and I'm including my brothers and my father. Because my family is very chauvinistic, in the sense that the boys are the ones that do the clever stuff and the girls should just look pretty. My mother suffered from that. My stepmothers seem to find that role appealing.

"After the conference was over," she continued, "Karl said, 'I'll call you in a couple of weeks.' The next day he rang. I said, 'Well, that didn't take very long.' "

I don't know whether Francesca told you or not, but when we first met I felt very strange about her work," Karl von Habsburg told me on the trip to Croatia I made with him, his wife, and his mother the week before Easter. "I had a feeling that this might be a thing that could wait. But I must say that by now I'm really impressed by what can be achieved for the spirit of the people by that work, and I think it's fabulous what she's doing. And I must also say that when I see our work—what she is doing, what I am doing, both going in absolutely the same direction, but with completely different ways of working—it's matching very well."

He also told me that two cars of his have been blown up in Croatia—"No, I wasn't in them"—and that he receives frequent death threats from Serbian extremists. We were standing amid the bombed-out ruins of a 16th-century Renaissance villa, on a hill outside of Dubrovnik. Before the war it housed the oldest library in the former Yugoslavia, but now its books sat in cardboard boxes, getting as soaked from the rain falling through the holes in the roof as we were. Karl was wearing his standard outfit: loden jacket, button-down shirt, Hermes tie, black Levi's, black Reeboks. Bom, raised, and educated in West Germany until he was 18, Karl joined the Austrian air force in 1984 after spending a year studying in Michigan with Russell Kirk, the grand old philosopher of the American right. He is now completing his doctorate in ancient history at the University of Salzburg, and still pilots in the air-force reserve. He likes fast cars, and dictates his political-opinion columns for Austrian and Spanish newspapers into a tape recorder while commuting between Salzburg and Lugano. He counts among his closest friends the crown princes of the ruling houses of Morocco and Spain. (The hot rumor in Madrid is that Karl's younger brother, Georg, is going to marry Princess Elena, the elder daughter of King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofia.)

Since 1986, Karl has run the Austrian branch of the Pan European Union, a conservative political movement committed to European unity and traditional values, which his father has headed since 1973. "Some people see it as a bit of a camouflage for the monarchist movement in Europe," says a well-placed Austrian aristocrat. "Especially since the Habsburgs have so much to do with it."

I asked Karl if he thought that restoring the monarchy—and there has been some talk of it in both the Austrian and Hungarian press—would be a good idea.

"Frankly, I just don't see it," he answered. "I mean, I really try to be absolutely down-to-earth in those things. And I think there are certainly more important things to think about and look after, so I'm not losing my time for that." He pointed out that in Austria, which first became a republic in 1918, "my name is Karl Habsburg, and that's it. Period." Yet he referred to the 1966 document his father signed, renouncing his right to the throne so that he could return to Austria, as "a completely ridiculous paper," and added, "/Ve never signed anything." He also told me that he "absolutely" wants to run for office in Austria in the near future, though he hasn't committed himself to a political party.

Last year, Karl caused a major uproar in the Austrian press and parliament when he agreed to host a daytime celebrity quiz show called Who Is Who? on state-owned Austrian Television. Though it scored the highest ratings for its time slot last season, the show hasn't been renewed, he says, because of political pressures from the Socialist Party. (There was also disapproval from another quarter: "We used to have subjects," one of Karl's Habsburg relatives is said to have cracked. "Now we have an audience.")

As Karl and I talked, Francesca systematically photographed the rubble around us. It was the third day of our trip, which hadn't been an easy one. Due to shelling in the Zadar area, parts of the coast road were closed, and we had to take a jammed overnight ferry to Split, where we spent the whole of the second day in back-to-back meetings at the Split Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments, the art and architecture departments of the University of Split, the local ethnological museum, and a Franciscan monastery. At every stop, Francesca was presented with requests for professional and financial assistance from her ARCH Foundation. From Split, we drove south along the Adriatic coast, formerly known as the Yugoslav Riviera. Hotels that had catered to German, Italian, and English tourists were now festooned with the laundry of refugees from Serb-occupied areas. Dubrovnik was pitch-black when we arrived, but fortunately we were staying at the one hotel with a generator, the Argentina, which was filled with refugees, black-marketers, and soldiers. Aside from a handful of UNESCO representatives, we seemed to be the only foreigners.

The next morning, the director of the Dubrovnik Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments took us through the old city and showed us nine Renaissance and Baroque buildings that had been bombed and burned. We also visited a makeshift conservation studio that had been set up in a monastery with assistance from ARCH . Three of the four young women working there had taken an emergency conservation course ARCH sponsored in Zagreb last year. (Three more courses, for about eight students each, are scheduled for later this year in Zagreb, Split, and Dubrovnik.) It was the only bright spot in a long afternoon of pouring rain and numbing destruction. From the ruins of the library we went on to the battered marina, the scorched airport, completely leveled country villages, and a small church in the middle of a field which had been axed to pieces.

At dinner that evening, Archduchess Regina said grace, as usual, and so did Archduchess Francesca. The next day was Good Friday, and they were leaving in the morning for the shrine at Medjugorje, just over the Bosnian border. Karl's mother told me that she has also been to Lourdes, Fatima, and the shrine of the Black Virgin in Poland, and that she is planning to make a two-and-a-half-week pilgrimage on foot from the French border to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. After Medjugorje, the Habsburgs were going deeper into Bosnia-Herzegovina, a region the family briefly ruled, to Mostar, a gem of Ottoman architecture that has been severely damaged by the Bosnian-Serb fighters still camped in the hills around it, and where battles broke out between Croats and Muslims in the city a few days after Karl and Francesca's visit.

I asked Karl if they would continue on to Sarajevo, the city where World War I began with the assassination of a Habsburg archduke. "No, ' ' he said with a pleasant smile, "I think that's one family tradition that I will not follow."

When you marry a Habsburg, history— for better or for worse—is hard to avoid. The wedding of Karl and Francesca, in fact, took place on the anniversary of the 1889 double suicide of Crown Prince Rudolph and his mistress, Mary Vetschera, at the imperial hunting lodge of Mayerling. "That wasn't the reason we did it," Francesca said. "The only other available date was Valentine's Day, and neither Karl nor I could face being married on Valentine's Day. It would have been just too kitschy." □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

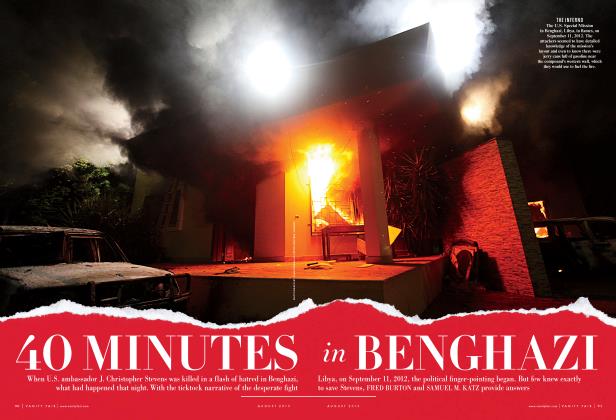

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now