Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

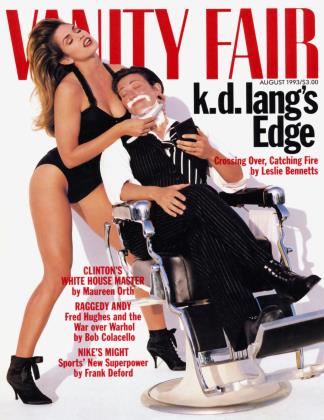

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPETE AND JOAN

Pete Peterson, Wall Street powerhouse and former secretary of commerce, has Bill Clinton's ear and a controversial book on the deficit due out this fall. His wife, Joan Ganz Cooney, was the driving force behind Sesame Street. At their Water Mill estate and their art-filled River House apartment, HILARY MILLS got a private look at one of the East Coast 's quintessential power couples, whose network of friends reaches into the highest echelons of business, politics, and the media

HILARY MILLS

Peter G. Peterson is on the phone with former senator Warren Rudman.

It is a crystalline spring morning, and as he talks to Rudman, Peterson glances out the window at the expansive wetlands behind his rambling $6million-plus oceanfront house in Water Mill, Long Island. Tall and rangy, at 67 Peterson has a palpable energy. He keeps moving as he talks, shifting his weight from side to side, running his hand through his dark disheveled hair. His red cashmere sweater is buttoned slightly askew, and one pant leg is caught disarmingly above his formidable calf-high leather boots.

We are in his third-floor office, where he has been trying to work on the health-care chapter of his book about the deficit, Facing Up, due out in the fall. This is hard going because the phone has been ringing all morning. The Council on Foreign Relations is on the verge of choosing a new president, and as chairman and head of the search committee Peterson is in urgent demand. The constant interruption of his concentration is unnerving, especially since he is attempting to do nothing less than restructure the Medicare system. "I'm not usually daunted by public-policy issues,'' Peterson says with uncharacteristic modesty. "But this one is the most daunting and hideously divisive, and could be the mother of all political battles."

Opposite his desk on a bookshelf is a small wooden arch painted with the words from a Disney fantasy: WHEN YOU WISH UPON A STAR. Above it is a framed letter from President Richard Nixon formally appointing Peterson secretary of commerce in 1972. The strategic placement of the two makes some sentimental sense for this son of a Greek-immigrant diner owner from Nebraska, but it also reminds me of a comment made by one of his friends. "I think Pete's career is a great testament to a statement made by Branch Rickey: 'Luck is the residue of design.' "

On the phone Peterson is telling Rudman that James Burke "wants the ex-senator on the board of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, where Burke is a trustee. Formerly the chairman of Johnson & Johnson, Burke is a good friend of Peterson's. Peterson seems perfectly happy to do him a favor on this busy morning, but he can't help joking to Rudman—in his characteristically charming/ abrasive way—that he wants his usual "10 percent."

Bringing the right people together at the top echelons of power has long been a Peterson trademark. The former chairman of Lehman Brothers and current chairman of the Blackstone Group, a successful investment boutique, Peterson is also—in addition to being chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations—chairman of the Institute for International Economics, on the board of the Museum of Modem Art, and the first outside American board member of Sony. As his friend Mitch Rosenthal, the president of Phoenix House, points out, "A couple of years at the center of power in Washington is the best postgraduate course in the world for social-political-corporate mixing."

Peterson has known Warren Rudman only a year, but they have become friends quickly because they share a common passion: the deficit. In fact, last summer, after Rudman announced his resignation from the Senate, Peterson conceived the idea of a bipartisan grassroots organization which would put pressure on the new president—whether he turned out to be Bush or Clinton—to substantially reduce the deficit. After he recruited Rudman and former senator Paul Tsongas, the Concord Coalition was bom and now has 75,000 active members, some siphoned off from Ross Perot.

Clinton seems to be paying attention. Right before his February 17 speech on the budget, the president turned to Roger Altman, his new deputy secretary of the Treasury and a former Peterson colleague at Blackstone, and asked him what he thought Peterson's reaction to his program would be. "I think the president respects Pete," says Altman.

The deficit is hardly a new clarion call for Peterson, who has been attacking Reaganomics since the early 80s, earning the grudging respect of both the Republicans—of whom he is one—and the Democrats. Even his old friend from the Nixon administration George Shultz, Reagan's secretary of state and a staunch defender of Reaganomics in his recent memoirs, says without a trace of irony, "I think Pete's work on the deficit has been heroic, and people are gradually coming to see how right it is. He's putting the political process on the spot to do something. He's a hero."

It was, in fact, Peterson's early work on the issue that originally attracted his friend James Burke. As chairman of Johnson & Johnson, Burke was then a member of the Business Roundtable in Washington, and, as he says, "everybody that I knew, virtually everybody, felt [Peterson] was the only one who was really articulating the issue in a way that people could understand."

The roots of Peterson's alliance with Burke actually go far deeper than business or public-policy issues, and perhaps this is one reason Peterson is so willing to do him a favor this morning. Peterson's wife of 13 years, Joan Ganz Cooney, was the first person Burke decided to bring onto Johnson & Johnson's board when it was opened to outsiders in 1976. She was already on the board of Xerox, so Burke called his Harvard Business School roommate, Peter McColough, who was then chairman of Xerox, to intercede on his behalf.

After breakfast at the Candy Kitchen, Peterson and Don Hewitt would go to the supermarket, to get back to their roots.

Being a member of five corporate boards is only a small sideline to what Joan Ganz Cooney actually does.

She is better known as cofounder of Children's Television Workshop, originator of Sesame Street, member of the Television Academy Hall of Fame, and Emmy Award winner for lifetime achievement in daytime television (not to mention more than 50 awards for the series).

This morning Cooney is just down the third-floor hall of the Water Mill house. She too is on the phone, facing the ocean in their all-white bedroom with her all-white Maltese, Matilda, at her feet. Trim in her tennis whites, her hair and makeup impeccable for a Saturday, Cooney seems, on the surface, more controlled and acutely alert than her husband. She has been talking to a female puppeteer about creating a new female puppet for Sesame Street. "It remains a big cause with all of us who are women on the show," Cooney says. "We want to make sure more and more female puppets get done. Jim [Henson] never thought that way, and it was hard to get it right over the years."

Given the fact that Sesame Street is one of the world's most widely seen television programs, the implications of Cooney's conversation this morning are considerable. That female puppet will have an impact on millions and millions of young consciousnesses—male and female—around the globe.

Peterson and Cooney's good friend Diane Sawyer makes the point that it is slightly "aerobic" being around the two of them for any length of time. "The energy has been a little higher and the things you've learned are startling. They have secrets, the two of them, and their secrets tend to be their passions about these big issues. In that way they are alike. They still believe that you can and must change the world."

True crusaders need influential friends to spread the word, and together the coupie has a power base that straddles surprisingly disparate spheres. At Peterson's 65th-birthday party at Tavern on the Green two years ago,

there was a heady mix of Establishment business heavyweights such as David Rockefeller, Felix Rohatyn, and Warren Phillips, plus a sprinkling of government

types such as Ted Sorensen and Richard Holbrooke. (Henry Kissinger couldn't make it.) But perhaps more significant was the preponderance of high-profile media people and journalists: Sawyer, Barbara Walters, Don Hewitt, Mike Wallace, Liz Smith, Peter Jennings, Roone Arledge, Mort Zuckerman, Warren Hoge, Punch Sulzberger, among others. For a businessman, even for a former secretary of commerce, that is a potent media delegation.

"Instead of foreign policy being made

Peterson and Cooney have understood the power of the press better and longer than most. Recently, Peterson even tapped two journalists to take major positions at the Council on Foreign Relations, an unusual move in the prestigious organization's 72-year history. Jim Hoge, former publisher of the New York Daily News, was made editor of Foreign Affairs, the council's bimonthly magazine, in June 1992, and Leslie Gelb, most recently a columnist for The New York Times, was chosen president of the council this May.

in the hallowed halls of the White House with some East Coast establishment elite or in the quiet Council on Foreign Relations, wise-men-style," Peterson says, "it's clear that the media—among other forces—is having a major impact on foreign policy, not just a reactive effect but a proactive effect. Foreign policy has become an open, if noisy, process."

Peterson saw the political potential of the media even back in the late 50s in Chicago, when his first mentor, Charles Percy, then C.E.O. of Bell & Howell, brought him in as his heir apparent at the young age of 32. One of Peterson's first ideas was to sponsor a serious news show during prime time. This was before 60 Minutes and 20/20, and no one thought a serious news format would work in prime time. CBS Reports with Edward R. Murrow became a major hit. "I saw then what the media could do," Peterson says. "We were getting loads of letters, awards, and editorial support, and, happily, our market share was going way up."

As secretary of commerce in 1972, Peterson, like his colleague Kissinger, preferred to socialize with the liberal press establishment—Kay Graham, Art Buchwald, Polly and Joe Kraft, among others—instead of with Nixon's cronies. Government and the press have always had a symbiotic relationship, but in the paranoid Nixon era such mingling was considered slightly reckless. "There was that famous moment when Nixon found him at my house," Kay Graham remembers. "I think it was the final blow. He and Nixon had differences, and Pete was fairly indiscreet and funny and got quoted in the paper with his irreverent remark about Nixon." ("My calves were so fat I couldn't even click my heels.") Peterson was let go after less than two years.

When Peterson began his anti-deficit campaign in the early 80s, Lesley Stahl, then anchoring Face the Nation, was inundated with notes from him, she recalls. "If I didn't follow up on something I'd get a little note saying it was good but you really should have asked X. He began to educate me." When she subsequently did a piece for 60 Minutes on budget cuts it was Peterson she went to for help, since his deficit program is largely about reducing entitlements for the rich and the middle class.

Ironically, Cooney, with her long history in television, made many of these high-visibility media friends —Sawyer, Walters, Stahl— through her businessman husband after they were married in 1980. And she is no less exacting of them. "Any number of times Joan has come to me with proposals for doing serious work, not to mention how that might presume to reflect on what I do now," says Diane Sawyer, smiling ruefully. "She's the first person to be on the phone to me the next morning if I've done a piece that she doesn't think lives up to what she thinks a serious approach should be. She's like the terrifyingly smart headmistress of some school which has very high standards. I love her for it. How many friends do you have who really do that for you?"

Liz Smith also says Cooney is constantly on her case. "She's always saying to me that I'm totally useless. I'll never write anything piercing or trenchant or mean about anybody. Then when I wrote something that was vaguely a slam, she called me to say she was beginning to have hope for me." When Smith gossiped about Henry Kravis's house party in the Dominican Republic, which the Petersons attended (uncharacteristically for them because it was such a chichi crowd), she referred to them all as "Barbarians at the Beach." "The day after, I went to Joan's house," Smith jokes, "and she said, 'Traitor! Traitor!' 1 said, 'I thought this was the kind of thing you're always urging me to do!'

Reagan speech writer Peggy Noonan, who met Cooney through a monthly lunch group started by Lesley Stahl, was quite taken with the originator of Sesame Street. "If you talk to her in the morning, she's read everybody's op-ed piece, including The Wall Street Journal. She likes ideas popping and she likes to connect them with people." Cooney found Noonan impressive as well, and they are now collaborating on a pilot on "values" for Channel 13, New York's PBS station, where Cooney is on the board. "I wanted to see more conservatives on public broadcasting," says Cooney, who is a longtime Democrat. "It's been criticized for not having more alternative voices. It seems at times homogeneous. Everyone is kind of Moyersesque. MacNeil/Lehrer is scrupulous about hearing from the right and the left, but in the end there's not much edge."

"To understand Joan, you have to understand the cancer. 'There is no dress rehearsal.' That is one of her constant lines.''

It's typical of both Cooney and Peterson to surprise you with a point of view, and this lack of ideological bias is central to how they operate. "Pete and Joan are pragmatists, practical," says Jason Epstein, editorial director of Random House. One of Cooney's oldest friends, Epstein met her in the late 50s through William Phillips, editor of the Partisan Review. "They try to see how to fix things, what's broken and what to do about it. They have no preconceived idea—or no conscious preconceived idea. We all have some kind of preconceived idea. But they don't operate from within a system. They don't have a set of beliefs."

Breaking through others' entrenched preconceptions, however, is part of their crusade. It was, in fact, at Epstein's kitchen table in Sag Harbor, Long Island, in the early 80s, that Peterson began picking away at that bastion of liberal belief, the sanctity of Social Security benefits. Cooney remembers feeling anxious about bringing her Republican businessman husband into Epstein's liberal literary milieu, but soon they were having Saturday-night dinners, often with Mort Zuckerman, Don Hewitt, and Felix Rohatyn. They all began talking about how the G.N.P.'s growth rate had declined and how no one in the country was adjusting expectations. They were just borrowing. Peterson had written an article for The New York Times Magazine in 1982 arguing that entitlements were going out of control, and it stirred them all up.

"We'd sit around that table and engage in this highly sophisticated dialogue of the deaf about these subjects," recalls Peterson. "They'd say, 'How can you be talking about reform? These entitlements are the very bedrock of the American social contract. We are just getting back our money from our accounts,' and on and on. I'd say, 'I have a lot of compassion for the people that need it, but I have very little compassion for the windfalls for the well-off. Do you have to bribe the rich to help the poor? If everyone receives, who pays?' That's the political basis of this free lunch: they bribe all of us and we pass the bill on to our kids."

(Continued on page 146)

(Continued from page 120)

The upshot was two articles on Social Security in The New York Review of Books which Epstein helped arrange with editor Robert Silvers. The Review got so many letters that Silvers devoted a follow-up issue to the debate. Mort Zuckerman too had become so intrigued by their talks that he put Peterson together with the editor of The Atlantic, which Zuckerman owns. "I had rarely met someone," says Zuckerman, "who was as articulate and knowledgeable in the sense that he not only had wisdom to bring to it but he had facts and analyses of the facts to support his conclusions." Peterson's article on the deficit, "The Morning After," was published in The Atlantic just weeks before the crash of 1987 and won a National Magazine Award for public service.

Suddenly Democrats even more than Republicans were beginning to recognize the validity of Peterson's ideas. Political lines were being crossed, and this caused some backlash from both the right and the left. In a devastating profile in Barron's, Joe Queenan called Peterson a "Cadillac Cassandra" and a "Schmoozemobile." Robert Kuttner in The New Republic made the point that "whenever selfless millionaires declare that 'we' must tighten our belts for the greater public good, the appropriate response is Tonto's 'What you mean "we," Investment Banker?' " Finally, William Greider summed up the economic opposition: the austerity measures Peterson proposed were just as bad as the disastrous advice that Wall Street's financial conservatives gave to Herbert Hoover in 1929.

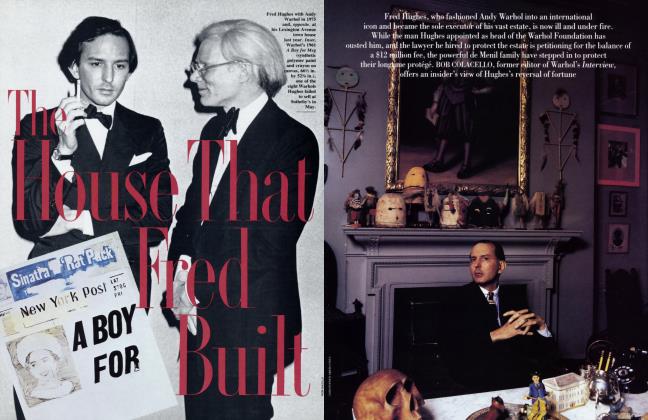

"If I were seriously in trouble," says Peter Jennings, "I would tell them about it and ask for their support "

Criticism of economic theories seems to come with the territory. But Peterson has also been the target of a far more serious and destructive, personal attack, one that haunts him to this day. In 1985, Ken Auletta published a two-part story in The New York Times Magazine about the fall of Lehman Brothers, where Peterson had been chairman from 1973 until he was toppled in an ugly power struggle with trader and co-C.E.O. Lew Glucksman in 1983. The following year Auletta expanded the articles into a book, Greed and Glory on Wall Street. Ironically, the book was edited by Jason Epstein, who had been so helpful in promoting Peterson's economic ideas only a few years before. Through the testimony of Lehman partners, Auletta painted Peterson as a self-centered, arrogant Establishment insider who made his subordinates feel like second-class citizens. Auletta also maintained that Peterson— egged on partly by Cooney—had been inordinately greedy with Lehman over the terms of his settlement when he decided to leave rather than fight.

The book hurt Peterson and Cooney profoundly, perhaps all the more so because Peterson had spent nearly every Sunday morning for three months giving Auletta his side of the story. That proximity may have augmented the problem. Even at their first meeting Auletta began to chafe. "I had all I could do to contain myself," Auletta says. ''As a journalist it's your project and he was talking as if it were our joint project, as if I was going to write an authorized Pete Peterson version. I felt like I was going to explode because I felt like this guy was trying to manipulate me. We were on the first date and he was running his hand up my leg and saying you're going to do what I say. I remember feeling exceedingly uncomfortable."

Auletta also says he was ''stunned by [Peterson's] tendency to make speeches at people." This tendency still exists. It's very hard to rope in Peterson's mind, to focus him once he goes striding off on a subject. He tends to make his own rapidfire transitions, and his thoughts keep spiraling outward with their own logic. One question may lead to a 40-minute answer. Diane Sawyer calls this "his great, rambunctious mind." It is consistently interesting if he is your subject. Following the way his mind approaches and tackles complex problems—whether international economics in the Nixon administration. Medicare, or our peculiar brand of democratic capitalism—is heady. But Auletta had a different agenda, as do many of those Peterson encounters.

"He's one of the most intellectually demanding people with whom I've spent time," says a former colleague at Blackstone. "His mind tends to race, and if it's a subject you're on, it's fascinating, and if he's on a subject other than the one you're on, he can appear aloof and distracted. But he's always moving." His partner Stephen Schwarzman, cofounder and C.E.O. of Blackstone, speaks of Peterson's brain with a certain reverence, perceiving it at times almost as a distant object: "It's a brain that is very powerful," he says. "It's methodical and logical and tenacious, and it gets you the right answers. The cells are all being used constantly. So the things that you would see interpersonally he might not see. Why? He's busy. It's different than normal people."

This "humanoid" aspect to Peterson has caused a lot of antagonism among people who don't know him well, but it is the source of amusement for some of his friends. Suzanne Goodson, ex-wife of the late TV producer Mark Goodson, remembers sitting right next to Peterson at a dinner party after he had come home preoccupied from a 3M board meeting. They made the usual party chitchat. The next day he greeted her as if he hadn't seen her in months. She finally realized he had absolutely no recollection that she had been there the night before.

Peterson is lucky now in that he has Schwarzman to cover his "interpersonal" flanks at Blackstone and Cooney to do the same at home. Cooney is passionate, intuitive, and tough. She forcefully reaches into his emotional life and diverts him from being the computer. Peterson himself refers to her as his "moral compass, inner-directed gyroscope, and outer-directed radar."

The marriage is the second for Cooney and the third for Peterson. All of their friends speak of it as a strong, devoted union. No doubt part of that strength comes from surviving difficult divorces. Cooney's first husband was a "brilliant but loony alcoholic," as their friend John Scanlon puts it. Originally a dashing figure in New York City mayor Robert Wagner's administration and a radical feminist when Joan met him in 1962, Tim Cooney was the one who urged his wife to go for the top job at Children's Television Workshop after she had put the project together. "Without him, " Joan Cooney admits, "I don't know if I would have gone as far as I went."

After Tim Cooney's career in politics petered out, Joan ended up supporting him and eventually paying him alimony. Epstein remembers him, near the end of the marriage, playing in a mud puddle in the country with the neighborhood children. He describes himself as a "functioning" alcoholic; his ex-wife supports him to this day.

Peterson's first marriage was brief. His second lasted 26 years and produced five children, so the divorce was far more shocking, in part because virtually no one saw it coming. On the surface Sally Peterson seemed the perfect government and corporate wife, giving lively dinner parties in Washington with home movies and popcorn, and later entertaining the likes of Mollie Pamis, Beverly Sills, and Barbara Walters in their lavish Gracie Square apartment. As Walters recalls, "When they first came to New York they were the most popular, sought-after couple. They were attractive, amusing, wonderful company, and seemed devoted. They entertained often and gave wonderful dinner parties. I don't think any of us realized what was going on."

What was going on was Sally Peterson's growing disillusionment with her constant role as hostess for the chairman of Lehman Brothers. It was the 70s, the height of the feminist movement, and she wanted something more substantive on which to hang her identity. She had raised their children and was at an emotional crossroads. She stepped up her studies in psychology, and, perhaps more significant, she started an affair with agent Michael Carlisle, who was 20 years younger and the son of her close friend Olga Carlisle.

A friend from their Washington days remembers being stunned. "I didn't have a clue that inside her was the diary of a mad housewife ticking away. I thought I knew her, but I obviously didn't. It just exploded." Peterson had gone into therapy a few years earlier, partly to placate his wife, but the extent of her alienation was a devastating shock. "He was grieved and obsessed by it," says Barbara Walters.

Cooney and Peterson clearly saved each other from the specters of their pasts, and perhaps because they have each undergone analysis they are acutely sensitive to anyone suffering similar pain. They reach out generously to others who are going through marital troubles or who have recently broken up with a partner. Both Stephen Schwarzman and Richard Holbrooke were asked to live with them after their unions dissolved. When Peter Jennings and his wife, Kati Marton, were having difficulties, it was Pete and Joan who counseled them. "If I were seriously in trouble," Jennings now says, "they are two people I would go and tell about it and ask for their support." Cooney has also given Marton an office at C.T.W. so that she can write her new book without the interference of children. "I don't know any woman who is more generous than Joan in wanting to pull other women along," Marton says.

After Jason Epstein broke up with his longtime girlfriend, Cheryl Merser, Peterson and Cooney kept in touch with her, offering her their weekend house when they were away. When she later got married, they gave her a wedding party and even insisted that the husband of her agent come. That husband happened to be Ken Auletta.

Cooney's gift for reaching out to others may stem from wounds that go even deeper than those from her draining first marriage to an alcoholic. When she was 26, her banker father committed suicide behind their comfortable house in Phoenix, after a serious depression. The tragedy sent young Joan into a period of anorexia, which today she considers a form of passive suicide. Maybe more important, in 1975 she underwent a radical mastectomy, and lives with the threat of cancer to this day. "To understand Joan," says Stephen Schwarzman, "you have to understand the cancer. Because of the cancer she has a policy of no bullshit. 'Life is too short, I could have checked out, I'm going to check out. There is no dress rehearsal.' That's one of her constant lines. Because of that she demands authenticity."

By the mid-80s Peterson himself was obviously no stranger to bad times. Only a few years after his wife Sally left him so ingloriously came the humiliating defeat at Lehman Brothers, Auletta's articles and book, and directly after that a failed partnership with an entrepreneur named Eli Jacobs (who filed for bankruptcy last April). By the fall of 1985, in fact, Peter G. Peterson, former secretary of commerce and former chairman of Lehman Brothers, was out of a job.

In his birthday toast to Peterson at Tavern on the Green two years ago, Mike Nichols suggested that Peterson understands plot. "He understands it is important to triumph after the trouble in the second act."

The triumph came at the hands of no less a personage than David Rockefeller. In October of 1985, Rockefeller recommended Peterson to succeed him as chairman of the ultra-prestigious Council on Foreign Relations. The Greek immigrant's son was following in the footsteps not only of Rockefeller, who had been chairman for 15 years, but also of "wise man" John J. McCloy, Rockefeller's predecessor.

"The Auletta pieces came out after he was considered a very serious candidate," says Rockefeller today. "But I didn't feel, and neither did the members of the board, that that should be a reason not to pick him. He's a very strong personality and not everybody is his fan, but I thought the Auletta pieces were unfair. ... He's a very capable person and I think he's done a very good job."

Other members of the council seem to agree. Peter Tamoff, former president of the council and now undersecretary of state for political affairs, says there were no problems with Peterson's management style, although he points out that Peterson does not have an office in the building. "There was never a trace of [arrogance]," Tamoff says. "In his dealings with me and the staff he was always jolly, easy, and very considerate."

The same month that Peterson was named chairman of the council he started the Blackstone Group with Schwarzman. Today the firm's annual revenues are anywhere from $50 million to $70 million, making it one of the most successful boutique ventures started in the 80s. Peterson and Schwarzman own a Bell 222 helicopter worth about $2.5 million. With two pilots and hourly operating costs of around $1,500, it is a luxurious way for Peterson and Cooney to travel to the Hamptons each weekend. Cooney, who originally asked for the helicopter, says she did so only because Peterson was traveling so much she worried about his health. "I don't like it as a symbol of how we live," she says. Still, theirs is a more than comfortable existence. In 1992, Financial World listed Peterson as taking home about $7 million a year—and that's a conservative estimate.

The four-and-a-half-acre Water Mill estate, which adjoins a nature preserve, has one of the largest waterfronts in the Hamptons. Peterson says he was able to afford it because of a windfall deal, but wondered at the time whether $6 million was a little too much to pay for a house. Cooney reminded him this wasn't a dress rehearsal—and went on to spend two to three million dollars on renovations.

In addition to the Water Mill property the couple have a spacious Manhattan apartment in the River House, its walls covered with Peterson's collection of contemporary art, mostly Abstract Expressionist: Rothkos, two new Diebenkoms, two Matisses, two de Kooning drawings, and a Miro. Peterson's interest in art is both aesthetic and financial. When he left the government in 1973 he "wasn't in very good financial shape," with no stock options and five children in private schools. He sold two Max Ernst paintings, which had cost him $7,000 in 1959, for $350,000. That enabled him to finance the renovations on his Gracie Square apartment, which he later traded for the one at the River House. One of Peterson's favorite distinctions in life is "first-rate first-rate versus first-rate second-rate." Although he unflinchingly characterizes his own mind as first-rate second-rate, he is adamant—primarily for financial reasons—that his art be only firstrate first-rate.

Having so much money is new to both Peterson and Cooney. "My assumption," says Peter Jennings, "is that he's phenomenally wealthy, but I never think of money when I'm around either one of them. The subject of money never comes up, and you don't notice money on him." Jennings and Peterson, in fact, have been seen washing dishes together after a party at John Scanlon's. And 60 Minutes executive producer Don Hewitt prides himself on the fact that after their Saturday breakfasts at the Bridgehampton Candy Kitchen he and Peterson used to go to the King Kullen supermarket. "We said, This is a good place to get reacquainted with your roots, who you really are, who's out there, who the people are."

The Candy Kitchen itself is a good place for Peterson to get reacquainted with his roots. Formerly owned by George Stavropoulos and sold in 1981 to Gus Laggis, another Greek, it clearly reminds Peterson (whose father was bom Petropoulos) of his childhood waiting on tables at his father's 24-hour diner in Kearney, Nebraska. Peterson has had an early breakfast at the Candy Kitchen almost every summer Saturday for the past 10 years, invariably joined by both Hewitt and Scanlon. The illusion of the power breakfast diminishes slightly when you realize that they are talking about real estate, golf, and the morning headlines, and are usually joined by assorted locals, rather than moguls. Ironically, however, this kind of casual integration is so rare and coveted in the Hamptons that it has its own kind of snob appeal.

Peterson may still feel at home in a diner, but he has been in the business of making money for a long time, and one wonders what ultimately motivates him. When I asked him about Blackstone after a wide-ranging discussion of public-policy issues, I was surprised to see his body deflate. The light went out of his eyes. I queried Cooney about this later. "I think there's no question that he'd rather engage in these other things," she says, "that he's more engaged intellectually. Blackstone is what he does for a living."

Scanlon has a theory that there are transformational people, people who actually change the world for a living, and transactional people, people who basically do transactions for a living. ''Joan is clearly a transformational person," he says. ''She has changed the nature of television. Pete is essentially a transactional person who wants at this stage in his life to be more transformational."

Cooney has already stepped down as C.E.O. of Children's Television Workshop in order to let David Britt take the reins. While still very active at C.T.W., she finally has more freedom to create new projects and is becoming more involved with her own foundation, which she has formed with her husband to support children's programs. At Blackstone, succession is a trickier problem. Peterson brings in most of the clients, and the word on Wall Street is that he and Schwarzman haven't created a company which could sustain his leaving. ''The biggest problem is that Pete and Steve have been completely unsuccessful in building a firm," says a Wall Street source. ''They've had enormous turnover. They both have the same attitude, which is that basically everyone is expendable." This same source insists that Peterson and Schwarzman own well over half the firm, but Peterson adamantly denies this, saying that he and Schwarzman own less than half and that he plans to give up more and more of his equity to junior partners over the coming years.

Peterson is still jumping planes to China and Singapore to raise money for a new investment fund for Blackstone, and it doesn't look as if he is going to stop in the near future. But at the same time, he is trying to resolve the vast and unwieldy questions of the deficit and health care. Peter G. Peterson doesn't like to be daunted.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now