Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWoodward and . . . Walsh

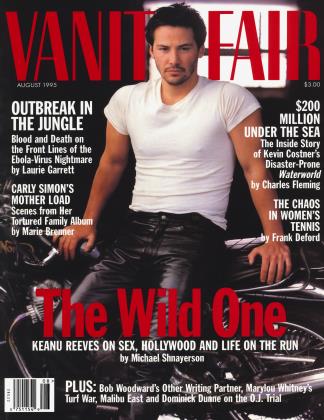

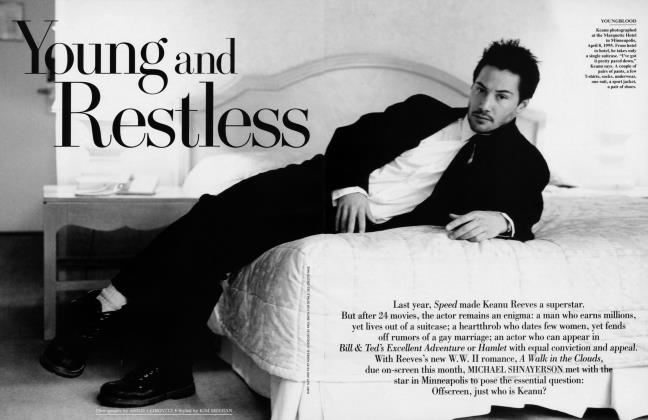

He was the twice-divorced hero of Watergate immortalized by Robert Redford in All the Presidents Men; she was an ambitious young Berkeley graduate. When Bob Woodward met Elsa Walsh, sparks flew in the Washington Post newsroom. Fifteen years and six Woodward best-sellers later, HILARY MILLS finds Walsh emerging from her husband's shadow with a new book, Divided Lives, and a new take on their marriage

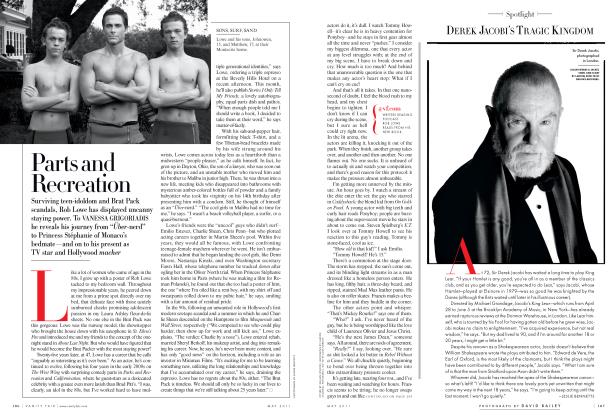

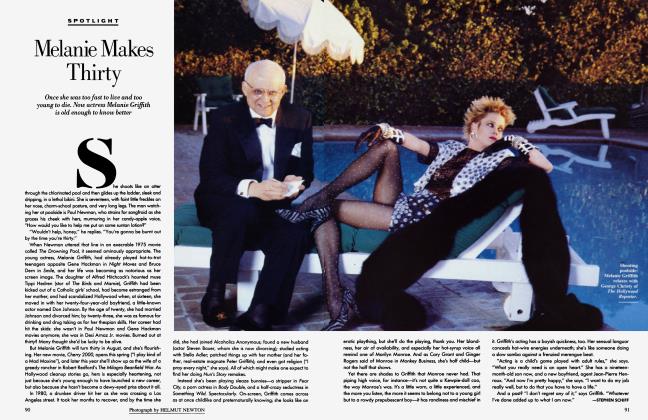

Fifteen years ago Sally Quinn, star writer for The Washington Post's "Style" section and wife of Post editor Ben Bradlee, shepherded a 23-year-old Berkeley graduate named Elsa Walsh across the legendary newsroom floor for a job interview with the equally legendary Bob Woodward, who was then "Metro" editor. Walsh, a tall, dark-haired Irish beauty who also happened to be Phi Beta Kappa, had read Woodward and Bernstein's All the President's Men and The Final Days with intense admiration. She had seen the 1976 Alan Pakula movie, in which Robert Redford made a virtual icon out of the man she was about to meet.

"Here was the real thing," Walsh remembers feeling as she walked into Woodward's office, "not something in a book, the real thing. Here was this person who had actually accomplished something good in his life. . . . The good man in the good society."

The admiration was instantly mutual. "It was the only time in my life," says Quinn, "that I have ever actually seen someone fall in love with another person in front of me. It was one of those scenes where you wish you had it in slow motion and they could show it in behavioral-science class. Bob just looked at her and almost couldn't speak. His eyelids started fluttering, and his mouth sort of dropped open. I looked at him and thought, Oh my God, this man is falling in love with this woman right now. I knew right away it was over for Bob."

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

"Bob just looked at Elsa," says Sally Quinn, "and I knew right away it was over for him.

Elsa Walsh got the job.

As I sit across from Bob Woodward in the apricot-glazed dining room of his high-ceilinged, million-dollar 1868 Georgetown house on a sunny morning all these years later, he confirms that moment with a shy smile which is prideful rather than embarrassed. "Sally is right in saying . . . yes, I fell in love with Elsa right away. . . . Elsa and I have as close a relationship as two people can have." The previous afternoon, as Walsh and I talked in the seductive hunter-green den with its deep tweed and leather seats, she had similar memories. "There was a lot of electricity in the air. It was a very powerful moment."

Woodward and Walsh started living together in 1982, two years after they met, and have been married since 1989, but the power of their union obviously hasn't diminished with time. As Quinn says, "He's extremely proud of her. I get the sense with Bob that he's constantly pinching himself and saying, 'How can I be so lucky to be with her?'" His pride extends to Walsh's career as a respected "Metro" reporter who was on the shortlist for a Pulitzer in 1989, and to her first book, Divided Lives, which Woodward's own publisher, Simon & Schuster, is bringing out in August.

Profiling the lives of three successful women—ABC correspondent Meredith Vieira, breast surgeon Alison Estabrook, and West Virginia's First Lady, the conductor Rachael Worby—Walsh reveals with unsettling intimacy how difficult it was for each of these women to achieve personal and professional balance. Advance praise has poured in from Doris Kearns Goodwin, Susan Faludi, Maggie Scarf, Mary Matalin, Linda Bird Francke, and Judy Woodruff.

"I think the most interesting book to come out of this house may very well be Elsa's," says Woodward with a humility that would be hard to believe if this particular character trait hadn't been confirmed by so many of his colleagues. At 52 he still has a boyish earnestness as he leans forward to make this point. The fact that he is wearing a tie in his own home this morning somehow adds to the impression of well-scrubbed sincerity. As Katharine Graham, chairman of the Executive Committee of the Washington Post Company, puts it, "Bob is wonderfully square, you know."

"The books I do," Woodward continues, "touch the lives of the people I write about maybe, and can explain some of the politics, but no one is going to read The Agenda and say, 'Ah, this is where I should invest my money. It s not about their life. Elsa's book is saying it's O.K. when it's hard, it's O.K. for the dilemma to be out on the table, it's O.K. to get frazzled. . . . It's taught me a lot."

Considering that Bob Woodward is the only nonfiction writer to have had six No. 1 New York Times best-sellers and that his seven books have sold more than four million copies in hardcover and untold millions more in paperback, this is a rather generous statement, even for a devoted husband. But what might seem patronizing to a jaundiced eye perhaps really isn't.

"They have the best marriage that I've seen, in truth," says Laura Yorke, a Putnam editor who is married to Dick Snyder, the former chairman and C.E.O. of Simon & Schuster, and who is in a similar union in terms of fame imbalance. "I think that they absolutely respect each other as people and for what the other does, and there's an incredible willingness to help the other person, to allow the other person whatever it is that they need to make them happy. . . . Elsa is very liberal and very much of a feminist and Bob is totally respectful of that. . . . More than any other husband I've ever seen." Snyder, one of Woodward's oldest friends and the publisher of all his books, is equally emphatic about the Woodward-Walsh relationship. "What I see," says Snyder, "and you don't often see it, is a great love affair going on."

Woodward knows what a love affair is not. He has been married twice before. His first wife was his high-school sweetheart, Kathleen Middlekauff, whom he married shortly after he graduated from Yale in 1965. He married reporter Frances Barnard in 1974, the year he shot to fame with All the President's Men. "I think he can count," says his friend Scott Armstrong, who grew up with Woodward in Wheaton, Illinois, and co-authored The Brethren with him. "This is the third time around and he's determined to make it work." Woodward's former boss Ben Bradlee agrees. "This is the first relationship that I know that he's had in which the relationship has been tended to. . . . He cares about how Elsa is reacting to his life. He cares about Elsa, which he didn't do with his other wives."

Woodward's unrelenting work habits have become the stuff of legend around the Post and caused friction in his previous relationships. "Francie would love to have her friends in for a chat," recalls Scott Armstrong. "Bob wanted to be out interviewing or writing."

Katharine Graham remembers that even before Watergate she had heard what a hard worker Woodward was. When she asked her son Donald (who was then apprenticing at the paper and is currently chairman, C.E.O., and publisher of the Post) whether Woodward might make a managing editor, he replied, "He's not going to be a managing editor, he's going to be dead. ... He works so hard he's a maniac."

Close friend Jim Wooten, a correspondent for ABC, was amused by Woodward's difficulties while vacationing. "We were down in the Virgin Islands several years ago sailing around," he says, "and all of us were very scrupulous—particularly the males—about pretending not to be interested in what was going on in the outside world. No newspapers, no telephones. One day we're sitting at a restaurant for lunch and Bob says, 'I'm going to the head.' So I followed him and he goes to the phone. ... I kidded him about it because I knew what he was doing. He was calling the Post."

Another friend, Post columnist Richard Cohen, says that over the years these kinds of caricatures have taken on an inflated life of their own. "There's a whole kind of Woodward mythology that's grown up," he says, "in which he's a Grant Wood character, a personification of American Gothic, and he just wants to work and he doesn't spend money and all this stuff, but some of it is overdrawn. . . . I think Elsa has given him another foundation, which is their relationship."

In Divided Lives, Walsh writes about the need for balance in life, an objective she clearly has been trying to achieve in her own existence. She separates this concept of balance into seven categories: work, love, children and family, friends, time for self, sense of place, and sense of self. Woodward has taken to this "program" with surprising zeal. "We do the seven levels of our lives pretty coherently and allocate time for them and don't get involved in a lot of stupid things," he confesses.

Woodward mentions with pride that he is trying not to work at night or on weekends, but adds somewhat sheepishly, "Elsa really is able to deal with me and accept my work habits, which still exist, and my impulsiveness sometimes and my nonrelaxed state. I'm in a nonrelaxed state doing this book on the 1996 elections because there is always something going on. Every day. I could spend all my time on it."

Walsh, however, makes sure that he doesn't. She has devised a series of evenings with friends where conversation focuses on a particular book or article. Participants include Post reporter and author David Maraniss, whose book on Clinton, First in His Class, was dissected in February. Other group members include Sally Quinn and, sometimes, Ben Bradlee, presidential historian Michael Beschloss, and psychoanalyst Judy Lansing Kovler.

Weekends are usually spent reading and relaxing at their stunning gray shingled house with a view of the Chesapeake Bay near Annapolis, Maryland, which they finished building in 1987. Walsh jokes about the guest wing, which because it overlooked the driveway tended to discourage visitors. But eventually so many friends came to visit—the Snyders, the Bradlees, Kay Graham, Richard Cohen and his wife, Leslie Feely, Jim Wooten and his wife, Patience O'Connor—that they built a guesthouse, with soaring, vaulted ceilings, which faces the water.

Over the years, the third-floor bedroom of their Georgetown house, dubbed the "bachelor turret," has also sheltered a small army of single, and temporarily single, friends, including Richard Cohen, Scott Armstrong, and Gary Hart (long before Hart's presidential bid, Woodward is careful to point out). Carl Bernstein stayed there in 1984, while he was starting his book Loyalties, his memoir of growing up as the child of Communist parents in the McCarthy era. The celebrated Watergate duo had gone their separate ways after writing The Final Days in 1976 because, as Woodward told J. Anthony Lukas in 1989, "I tend to be more of a workaholic and Carl tends to be on the lesser side of workaholism." Although friends originally called the town house "the Castle," because of its architectural style, the top floor was later named "the Factory," to commemorate the vast number of pages generated in the suite of three offices where Walsh and Woodward spend most of their days.

Although Woodward had a sailboat called Timeless in the mid-80s, he sold it because finding a crew was too time-consuming. He and Walsh now scull on the South River, and Woodward tries to play golf every couple of weeks. Walsh even has him going to the gym and working out with a personal trainer. David Maraniss is intrigued by all the physical-fitness paraphernalia the two have. "Elsa is sort of a self-improvement-type person," he says, "and I think she has gotten Woodward on that kick, too."

Cultural self-improvement is also part of the balance Walsh seeks, and she and her husband go often to the symphony or the opera. But they shy away from the celebrity social circuit because, as Woodward says, "it's meaningless. It's not real." In fact, Woodward's ability to resist the more tempting seductions of fame probably saved him after Watergate, when he and Bernstein—who fared less well—became overnight national folk heroes.

Walsh's avid search for balance clearly stems from an intuitive realization that she herself was falling prey to Woodwardian excesses at one point. There was a period in the 80s when she and her husband barely saw each other. "Essentially from 1985 to 1991 was just sort of a working jog," she admits. "Often I wouldn't come home till 9 or 10 o'clock. Even though I thought Bob and I had a really great life, we didn't go on a honeymoon right away because I was covering a big drug trial. I got married just as I thought the jury was going out for deliberation."

Not only was Walsh beginning to work as hard as her husband, but the focus of her pieces was gradually changing from human-interest stories to the more hard-edged investigations for which Woodward is famous. Part of this shift obviously had to do with the advancement of Walsh's career as she moved from the suburban-weekly "Metro" section to an education beat and finally to covering the D.C. superior courts. "She covered some really gruesome trials," says colleague D'Vera Cohn. "It's always amazed me she wanted to take on some of the horrific and terrible crimes."

Sari Horwitz, who reported on crime at the same time as Walsh, understands the addiction. "It can get rough, and I think people were surprised a little bit that people like Elsa and I were doing it. . . . It is considered a grimy, dirty beat, but I think both of us got (Continued from page 126) sucked into it. Every story was dramatic and compelling."

(Continued on page 148)

"What I see," says Dick Snyder, "is a great love affair going on."

(Continued from page 126)

It is hard to imagine Walsh in this environment, since she is a graceful, feminine 37-year-old with an infectious laugh, a sense of style, and a serious literary and intellectual bent. But ferreting out the grim reality of these underworld lives apparently intrigued her. "It interested me too much, actually," she says. "I thought I was really getting to the nub of the human psyche. After a while I realized I was getting a completely distorted view."

D'Vera Cohn noticed a growing similarity between Walsh's approach to journalism and that of her husband. "As they've known each other longer, it seems to me that Bob has had more of an influence on her work and that he helped her become interested in becoming a more hardnosed investigative reporter . . . pursuing stories designed to unearth wrongdoing or things that weren't working the way they should be, rather than digging deeply into people's lives, which is possibly her own interest. On the other hand, with this book she is getting back to that."

Walsh's sister Diana, a reporter for the San Francisco Examiner, says Elsa was always looking for someone to lead her. "She says that she always was looking for a mentor, and Bob became the mentor. ... I think he really pushes her in a way that maybe she wouldn't push herself, because he has that drive."

Walsh readily admits that Woodward is a mentor, although she insists he lets her be whatever it is she wants to be. She does share some of her husband's methodology, such as going back and reinterviewing sources over and over again, writing a memo after every interview even if it was taped, and trying to write 10 pages a day, as he does, when she was working on her book. But she says she doesn't feel in any way eclipsed by him, and perhaps her feminist book is her move away from that possibility.

"Bob was who he was when I met him," she emphasizes. "It would have been different if we'd both been 23 years old and he did something really good. ... I know a lot of my friends worry that I should get some recognition in my own right, because they say that to me. I say to them I'm not in competition in the marriage. . . . Now, I may be fooling myself about this."

Writer and feminist Linda Bird Francke suggests that in these sorts of marriages there usually is some kind of inherent stress. "I think it's probably extremely difficult being married to a Bob Woodward," she says, "because he tends to overshadow whatever anybody in his immediate family does. It's harder to establish yourself as a person in your own right if you're married to a star within that same field. If she were a star surgeon it would be much easier. I think it makes you more ambitious so people take you seriously in your own right. It adds a whole other pressure."

Despite the powerful initial chemistry that Quinn remembers, the relationship faltered after Walsh arrived at the paper. "It was difficult," she recalls uneasily. "He was the 'Metro' editor and I was a reporter on the weekly staff and in the chain of command he was ultimately my supervisor. It would have been different if we were colleagues."

Scott Armstrong remembers talking to Walsh during the rough periods. "Elsa, when she met Bob, was anxious to continue the relationship and was quite charming in her concerns," he says. "It was a complicated thing. Newsroom relationships are always complicated; obviously you can't be going out with your boss. She was smitten and didn't quite know what to make of Bob. . . . She wanted it to go further, and I think she had to decide that was something worth going after. There were lots of distractions for Bob at that time—other women and work. . . . Elsa made sure she was around. It was deliberate in the best sense of the word. My suspicion is that left to Bob reacting the right way at the right time they wouldn't have gotten together."

The professional imbalance was difficult enough, but right after Walsh and Woodward started dating, a major trauma erupted in their lives which made their relationship even harder.

Walsh had become friends with Janet Cooke, a glamorous, ambitious black reporter who was a fellow rookie on the suburban-weekly beat. Cooke had just written a moving piece for "Metro" in September 1980 about an eight-year-old heroin addict named Jimmy, whose tragic story became a cause celebre as soon as the article was published. Cooke was subsequently promoted by Woodward to be a full-time reporter working under him in "Metro," and not long afterward she received a Pulitzer Prize for "Jimmy's World."

Walsh had been living with Jim Wooten and Patience O'Connor since her arrival at the Post, but the Wootens needed more space. And so, shortly before Cooke received the Pulitzer, Walsh moved into an apartment with the paper's new star reporter. She also began dating the paper's star editor, Woodward. As her sister Diana points out, "Elsa was always attracted to the stars. She dated the quarterback of the football team in high school and Ed Gargan, the editor of the Berkeley paper, The Daily Cal, who went on to the Times.'''' For a short while things were fine—until it was discovered that Cooke had been lying about the Pulitzer Prizewinning piece: there was no Jimmy. Cooke had created a composite.

In April 1981, just a few months after Walsh had moved in with her, Cooke was forced to give the Pulitzer back. Since Woodward was Cooke's boss, he was deemed ultimately responsible. "The memory is a good repressor," Walsh says edgily. "Bob and I talked about it. It was very hard for him, very difficult. What really made me love him even more than I had is that he was in pain not just for himself but because he recognized he should have gone out and tried to find the child [before the piece ran]. ... It goes back to this notion in my life—being raised as a Catholic and then going on to study rhetoric, which is all about the good man in the good society. For me Bob always represented that."

After the Cooke fiasco it was clear to most Post staffers that the shining knight of Watergate was no longer in line for Ben Bradlee's job as editor of the paper, although Kay Graham today says that incident was not the reason. "Some people are writers and some people are editors," she says. "Bob is much more of a reporter and writer. He hired well, he did a lot of things well, but I just don't think it's his main preoccupation."

In order to keep their star reporter content without the editorship, the Post created the investigative unit for him. More important, the paper gave him complete freedom and flexibility to write his books. Indeed, the time he spends away from the Post now far exceeds the time he puts in. He edits the "Weekend" section three or four times a year, but last year he wrote only one story for the paper, with Ben Weiser, on the children's disability program. So far this year he's written no stories. "This is probably the least involvement with the paper he's ever had," says executive editor Leonard Downie, "because we have many political reporters covering the same campaign that his new book is going to be about."

For this minimal involvement Woodward is paid a salary of well over $100,000 (according to Bradlee). In exchange, the Post gets first serial rights to all his books. There have been questions about the journalistic ethics of this arrangement, since some feel information that should be in the paper is hoarded for books which earn Woodward and Simon & Schuster a lot of money.

Downie doesn't see the conflict. "It's a question of when the information should appear. Should it appear as soon as he finds it out, which we've done in many cases, or is it best in the context of the book and in the context of the serialization of the book? . . . I've never felt with any of his books that he withheld something from us."

There have been other quibbles. Woodward's refusal to name sources in his books in order to ensure his access has bothered other journalists who are held to a different standard. Tony Lukas, two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, doesn't like it. "I think there are times when it's very difficult to disclose sources, but it's not as difficult as Woodward pretends," says Lukas. "Woodward would have you believe that the only way of gathering information is by guaranteeing confidentiality. I'm not so sure of that. ... I don't think it's only the refusal to name sources that bothers people. I think it's the tendency to see the subject through the eyes of those people who are his sources and often punish those people who don't talk to him."

But this isn't always true, either, as Mrs. Graham makes clear. "Look what he did to Dick Darman [budget director under Bush], who was a great friend. [Bob] ran some very sensitive pieces about him. He interviewed Dick, who I believe said he didn't quite believe in Bush's economic plan. [Bob] did in his great friend and lost him."

Ben Bradlee remembers the tugs-ofwar he and Woodward would have about the equitable sharing of information between his books and the paper. "He'll sit on stories until he has lunch with me one day and I'll say, 'Goddamn it—you have to unload some of this stuff because it won't last.' And he'll write a couple. He'll always do that. I love stories, I love stories in the paper, but this man has given us an enormous amount of them, enormous, and, greedy as I am, if I make him do it, he'll quit. And why the hell shouldn't he?"

Columnist Richard Cohen agrees. "Face it, the guy doesn't need The Washington Post. He's a multimillionaire and the bestselling nonfiction author of all time. I think first comes the Bible, then Woodward. He's a phenomenon. He could probably buy The Washington Post, or at least leverage it so he could buy it. He's rich, he's really rich."

For a journalist, Woodward is really rich. Bradlee estimates his net worth as far more than the $8 million last reported in an unauthorized biography by Adrian Havill because, as Bradlee puts it, "he's got the first nickel he ever had. He invests wisely." So why then does Woodward stay even nominally connected to the Post?

"Bob always goes home," says Dick Snyder. "He always goes back to the Post. I think he always wants home, although now that home is changing. Ben is not there. Katharine is not really there. But it's like every now and then drop in on your mother."

It has been speculated in the past that the familial connection Woodward felt toward the paper stemmed from an emotional hollowness in his early life. When Woodward was approaching adolescence his parents went through a difficult divorce, which left him feeling abandoned. His mother moved in with another man, and he and his two siblings were taken by their father, a judge.

For the small, solidly Republican town of Wheaton, Illinois, in the late 50s, this was rather a shocking social specter. Woodward's father then remarried, to a woman who already had three of her own children, and together they had one more child. "You end up feeling like an outsider in your own family," Woodward said in 1989.

If Woodward's Wasp midwestem family was essentially dysfunctional, Walsh's was the reverse: a tightly knit and loving Irish Catholic immigrant brood of six children who lived in the Bay Area near San Francisco. She considers her mother to be one of her best friends, so it was hard for her to accept Woodward's alienation from his mother. "Bob felt abandoned," she says. "I always told him there's probably another side to the story, and you don't want to have regrets about not having reconciled." Though Woodward never took Walsh to his hometown, his mother visited them for Mother's Day shortly before her death in June 1989. Later that summer, Woodward asked Walsh to marry him.

"After his mother's death," says Walsh, "we were out in our house in Maryland and we had taken her dog, Freddy, a little Maltese. We were sitting out on a beautiful summer night having a glass of wine and dinner, and we were talking about how good our life was and how short life was, though. From quite early on in our relationship we had come up with this notion about 10,000 days and that we would be lucky if we got 10,000 days and that you really had to live it. He turned to me and said nothing would make him happier than if I would marry him. And I said, well, nothing would make me happier. It was so surprising to me that I would feel so—that obviously I wanted it and I wanted him to say exactly those words to me."

Walsh says that because she came of age at the height of the feminist movement, with role models such as Gloria Steinem, "my two mantras in life were 'I'm not going to get married and I'm not going to have children.' ... I don't know whether you've said something so many times in your life that, one, you really think you believe it and, two, even if you don't believe it any longer it's difficult to say it. ... I realized at that time that if I was so wrong about marriage maybe I was really also wrong about having a child."

In the afterword to Divided Lives, Walsh admits that she undertook the book partially in an effort to understand how other women coped with having both children and professional careers. She was hearing horror stories on both ends of the spectrum: women with children were feeling tom and guilty because of the lack of time with their kids, while women who had decided not to have children were deeply regretful.

During her research, Walsh realized that children weren't necessarily the issue. In fact, two of her three profiles are of women without children, Rachael Worby and Alison Estabrook. Worby had trouble integrating her role as a conductor into her life as First Lady of West Virginia, and Estabrook had trouble advancing within the Old Guard medical male bastion at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York City.

The real problem, Walsh felt, was that these women concentrated on one area of their lives to the exclusion of others. None of them was very practiced at compromising. Walsh concluded that balance is essential in life and, after finishing the book, finally made the (very deliberate) decision to try to have a child. She says she may or may not return to the Post. "The frustrating thing about daily journalism is that you don't really feel you're connecting, even though you're like this wonderful little firefly—you're in the fire and out. But the question is, are you learning the truth?"

Bob Woodward could tell her a thing or two—and probably already has. "With a book you have a chance to get to the bottom of something," he says. "Getting to the bottom. It really is that simple."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now