Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowANNIE HALL DOESN'T LIVE HERE ANYMORE

Hollywood

Beneath the ditsy, eccentric camouflage, Diane Keaton has been doggedly pursuing a new career—directing music videos, after-school specials, and, now, a much-praised feature, Unstrung Heroes

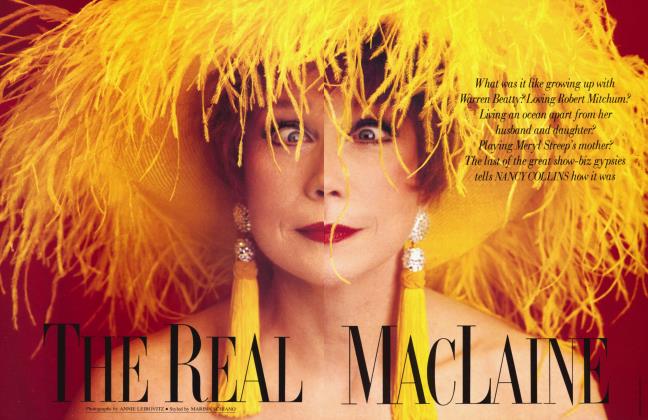

NANCY COLLINS

'My mother was Mrs. Los Angeles in the Mrs. America contest," says Diane Keaton, eyes gleaming through her clunky horn-rims. "Oh, it was the biggest, most fantastic thing, particularly when she was crowned Mrs. Highland Park. Can you imagine seeing your mother standing up there onstage with all those appliances? It was like the most extraordinary dream, sitting in the audience, and suddenly there's your mother in the spotlight with the microphone, and a cornucopia of gifts. Oh, God, it was so amazing. I thought, I want to be on that stage, too."

In Diane Keaton's dreams, there are always appliances. Appliances, and spinning globes, and bowler hats, and tiny bride-and-groom statuettes from wedding cakes. Crazy things in technicolors, talismans in pastels. Not only does Diane Keaton collect things, she loves them. And not merely for the irony. Her attachment to her treasures is more sentimental. There's a wistfulness; it's as if she's trying to hold on to something.

Her imagination must closely resemble the relic-laden apartment where the crazy uncles live in Unstrung Heroes, her much-praised debut as a big-time movie director. You can picture those rooms: painted in Hopper colors, shelves stuffed with Annie Hall's castoffs, old gizmos, photographs in sepia tones, and souvenirs of California, where Diane Keaton was raised in "a typical tract house in suburban Santa Ana."

Most of the things you'd find in Diane Keaton's imagination are mementos of home. After her 1977 Academy Awardwinning performance as Annie Hall, we thought home was Manhattan for this woman who epitomized West Side psychodramas and eccentric downtown chic. Her most memorable screen characters—vulnerable, Rorschached to the maxhave been thoroughly modern, thoroughly screwed up. Who can forget Keaton's Mary Wilke in Manhattan breaking down over the unavailability of her analyst? ("Donny's in a coma. He had a very bad acid experience.") Or the moment in Alan Parker's Shoot the Moon when Keaton, as the abandoned wife, sits in the bathtub getting stoned and softly singing an old Beatles song as the tears fall? In the pauses punctuating Keaton's sentences, you heard the reservations of a generation of women. In her signature performances, she transformed self-doubt and high anxieties into gentle performance art. All by herself, she was a comedy of manners.

Before you could say "la-di-da," Keaton was an icon onscreen and off. What she wore, everyone else wanted, too. She reigned over Central Park from an all-white apartment in the San Remo, treetops away from Woody Allen, her director, onetime lover, longtime pal. But Annie Hall doesn't live there anymore. And Diane Keaton is older, wiser—different.

"The things they mythologized about me are over," says Keaton, who is 49. "But the residue remains ... like wearing too many clothes, hiding out, being insecure, not finishing a sentence. It wasn't who I was then. Nor now. It was just easy for people to say, 'Oh, that's identifiable, and in her we like that.' Once in a while, it creeps in, but it's about the past."

On a steamy Saturday, Diane Keaton— her face as beguiling as your w grandmother's cameo—is sitting in my house in her shiny black loafers (size 10) and baggy blue jeans. Her white long-sleeved blouse is buttoned tightly at the neck; her leather jacket hangs almost to her knees. It's August; she's dressing light. She has arrived, a Chaplinesque vision in a black bowler hat, bearing teapot. It holds a brew of honey, lemon, and tea which she hopes will soothe her nagging cough by the next morning, when she begins shooting Marvin's Room, in which she'll co-star with Meryl Streep and Robert De Niro.

But she's not here to talk about acting. Today she's in her director's mode. Diane Keaton has made a movie about mothers and fathers and families and kids and dying—and the mystery of it all. The hero is a 12-year-old boy trying to survive while his mother fades away. As her days pass, he collects her things—a tube of lipstick, a spool of thread—and hoards them in a secret box. Unstrung Heroes is Diane Keaton's secret box, filled with objects of memory, replete with feelings. When Andie MacDowell, the terminally ill mother, wraps her hand around her son's fingers, kisses him, or smooths his hair, it is the essence of motherhood.

"Diane gave me more ideas than anybody I've worked with," says MacDowell. "She showed me these photos of this woman who was her neighbor in Santa Ana who always fascinated her, the shoes she wore, her jewelry. Diane suggested one piece of funky jewelry that really gave me an idea of who the character was—very sensual, sexy. The red lips, the nails. I love those. Those were Diane's ideas, too."

"I was attracted to Unstrung Heroes," Keaton begins, "because of the mother. She was the heart of the piece. I have very strong feelings about my own mother, who is a very special person to me. I wanted to make Andie the kind of mother you want, somebody you just couldn't stand to see die."

Though Keaton's own 73-year-old mother, Dorothy, is still very much alive, her father, Jack Hall, a civil engineer, died five years ago from an inoperable brain tumor. It was his illness which took Keaton back home to Los Angeles, where she lives now in the Hollywood Hills, a latter-day Georgia O'Keeffe with her dogs and Land Rover in the house once occupied by the silent-screen star Ramon Novarro.

'I did not buy the fantasy of Prince Charming and all that garbage."

"I wanted to be closer to my mother, my sisters, my brother, all of whom—with one exception—live in California," Keaton says as she consumes a rather prodigious helping of chicken salad. "Time is precious. Important. You don't want to miss any moment you have with your family. I don't. All my casual, fun time is spent with them. Some people may not want or need their families as much as I. But I have never quit on my family—being the daughter, the sister, my relationship with my mother. My father, of course, is not alive." She turns her head, embarrassed, as her eyes fill with tears. "My father's death changed the whole panorama of my life. This movie is about how the loss of a member of your family can bring you closer to other members of the family. I think that's the theme in a way.

"I didn't know my dad nearly as well as I know my mother," she says regretfully. "However, I felt a tremendous closeness to him regarding performing. My father was extraordinary, like a light, when he would come backstage. I had his attention in, yeah, oh boy, a big way. I'll never forget the first time—this is so stupid. I did Little Mary Sunshine in high school. My father was radiant. I was shocked. I didn't know what I had done that made him so excited.

"There was something sweet and kind of innocent about my father in a strange way," she adds.

When I suggest she has those qualities, her face contorts.

"Ughhhhhhh!"

Time passes; things change. What once came easily to Diane Keaton no longer does. And she doesn't try to hide it. "I've had to work harder," she says, quite frankly, of the last few years, when her stardom dimmed a bit. "I've had to work much harder to do what I've done," she tells me without flinching. "After Annie Hall, things came to me much more. Now I'm much more aware of working hard to get to do what

I do." The acting roles, she says, have been difficult to come by. "Once in a while they aren't," she admits, seeming almost ashamed, and citing her latest acting vehicle, Father of the Bride

II (in which she again co-stars with Steve Martin). "Well," she concedes, "that's a sequel. I mean, hello. Yeah, well, everything else has been hard to get."

But then, Diane Keaton has never conformed. Behind her on-screen camouflage, there was always an artist, a woman, quietly breaking the rules—mocking bosomy-movie-star seduction in whimsical high-necked wardrobes; subduing her allure under millinery fit for safari; hiding out like a recluse in the residential hotel called Hollywood. Keaton has always rebelled. Quietly. She didn't announce her intention to direct. She just started doing it, spurred on by her love of photography. (Knopf published Reservations, a collection of her photos of decrepit hotel lobbies, in 1980.) She began with rock videos (Belinda Carlisle's "Heaven Is a Place on Earth") and an after-school special for children, working her way up to episodes of China Beach and Twin Peaks. Critics sent her first major directorial project, a quirkly little documentary called Heaven, to eternal purgatory. And Keaton—hardly the quintessential optimist—seems not to have been the least bit surprised. "I was killed," she admits candidly, not looking for excuses. "It was just one of those things that was critically a disaster." But she just kept auditioning. Just kept on going.

"I had to go in, do the work, and fight for it," she says, stomping the floor with one of those big, shiny loafers. "Really fight for it!"

Diane Keaton says she has always been ambitious. It just took her a while to realize it. She calls herself "a late developer," and concedes that "it took years and years before I would even admit to myself that I was ambitious.

"But cumulatively, over time, it added up, and now I'm very well aware of it. ... In my family, I was the overblown personality, the loud one, the one who got carried away. I was overbearing, probably because I was more driven than the rest. I am the most opinionated person. I know what I like quick." She snaps her fingers.

Ambition, of course, complicates everything. "It can get in the way of a lot of things," she contends. "It can get in the way of a lot of other experiences because you're consumed. Which can eat up a lot of time."

"What I really am," she says happily, "is dogged. I'm a worker. I pursue things persistently, She laughs. "There's a lot to be said for just showing up."

don't . . . Nah, not for me. Not really. I don't think so." The question is whether Diane Keaton has ever wanted to get married. Or ever will. Certainly she's kept impressive male company: Woody, Warren Beatty, her director and co-star in Reds, and, a little more recently, A1 Pacino. Yet, even so, she seems to indicate that marriage to any of them was never an issue.

"I was mad for Barbra Streisand," says Keaton, remembering her own early 20s. "When she first started singing, she sang a song called 'Never Will I Marry.' I remember singing that song and thinking, Mmmmm, gee, it would be a shame if in some way you didn't marry. But, on the other hand, there was always something that song said to me. I always think about it."

Yet, when you are 49, independence doesn't come easy or without regrets. "When you're feeling depressed or insecure," she says, "of course you say, 'Yeah, I should get married.' But when I was growing up, nobody said to me, 'My God, you must get married, dear.' My mother never did that. She also did not say, 'Have kids.' No, she did not! No! No! No!

"I do not have a family I've started on my own, but that doesn't make me strange, unusual, unhappy, miserable, sad, or missing some really important human values in love. I don't feel any of those things. When you're with somebody, those feelings are still there. When people say, 'Isn't it a shame?' because a woman is not married, it means nothing to me.

'The things they mythologized about me are over, says Keaton.

"I feel lonely sometimes, naturally. Everybody does. But I don't consider my life lonely. Honestly, I do not think I'm really a cozy type. I mean, I'm sorry. I don't ever cuddle up too much to anything, except my dogs. It's misplaced affection, but what can I say?

"I don't feel like I'm out there alone, exactly. Certainly when I was with men, I didn't feel buffered from every storm because I was with them. You can't get that from somebody else. I did not buy the fantasy of Prince Charming and all that garbage. Otherwise I wouldn't have had this kind of life. Somewhere I always knew that."

Diane Keaton lives alone with her two dogs—actually three, if you count her housekeeper's. Her life is a work in progress. "Diane has an appetite for the creative side of life," says her old friend Carol Kane. "She's a big learner, a big trier, a big liver. She never wastes a day. The sun comes up and she feels she ought to be up with it." Besides work (after Marvin's Room she starts The First Wives Club, with Bette Midler and Goldie Hawn), Keaton's got lots to do. "I'm always busy," she assures me firmly. "I can't not do things. That's like my mother. I have to be busy. I'm a collector of junk, and I have a library of photography books. I love to go to bookstores. I love to go to the swap meet, to go down to the beach. I have a house in Arizona and I drive there. I love to drive as long as I can listen to books on tape, which is really fun for me.

"And I have my dogs. I love them. I had cats, but when I was 39 I got asthma, so I had to let them go. So, I have two dogs, mongrels that people threw at me. I see my sister Dorrie all the time. We go to pottery shows. I'm a big fan of California pottery. I'm very interested in architecture. I like a lot of things related to looking and seeing. I go to movies all the time." She laughs. "I pay. I don't like the screenings, because I feel like it's much more fun just to go. I go by myself all the time. Sure, why not?"

Though she assures me she's not in love now (No! No! No!—Keaton habitually demurs in exclamatory triplicate), she's still cursed with a romantic heart. Unlike some who have opted for art over love, Keaton still remains fascinated with the art of love.

"I heard Jeanne Moreau talking about love on television one night, the difference between being infatuated versus love that supports the kind of person you want to be. I believe in marriage. But I believe it has to come from that kind of love. That is unimaginable to me—in relation to men. I feel that way about my family—and some close friends, too. But I've not experienced that kind of love with a man yet—at least when the sexual thing is part of it. I don't think I've ever hit that kind of love on the mark."

I mention her array of flashy former paramours and ask if it's hard to navigate a relationship with a man of, shall we say, a certain ego. "Sometimes it's not easy for them to love me either," she says, "somebody who has a drive toward a lot of other things than that which is expected. I have plans, things that consume me, that might not make it so easy to be with me."

Suggest that Beatty or Pacino might come with his own basket of peccadilloes and Keaton reverts to the apologetic Annie Hall charm she still relies on in a jam. "I really can't talk about those guys. It's not right. I hope I can stick with it. I hope I don't sell out: every time I've said that about something, I've always done it."

She will say only that she has met Annette Bening, who is now married to Beatty. "Warren made a good choice. She seems great. And it's also great for him that he has children. Warren is such an emotional person, very emotional, so I think he would just love those kids. I knew he would be in love with his children."

Keaton's own decision about having children has been very conflicted. "Oh, God," she says at the mention of the subject. "That's a complicated matter. Let's definitely not talk about that one. 'The kids thing.' Is there another thing we could talk about, like getting older in films?"

'I had to fight for it," Keaton says of her new directing career. "Really fight for it."

ast May, as the final credits rolled on Unstrung Heroes, the Theatre Claude Debussy at Cannes filled with the kind of applause directors die for. But Diane Keaton didn't hear it. "I wasn't there," she laughs ruefully. "I was supposed to introduce the movie, which, of course, I didn't. I didn't know how to, so I stood there and let Andie MacDowell do the talking. And then I left. You'd think a director might enjoy watching her movie with an audience. But I absolutely never want to do that again. No! No! No! I'm too sensitive about the response. I can't take it.

"It's been great to have the opportunity to make this movie, but if I could, I would just put it away and never show it. That's the immature part of me. I love to do the work. But I don't want to go through the response part. I just want to walk away from it. There's nothing I can do about it anymore."

Unstrung Heroes may well make Keaton a sought-after director. But she's still got reservations. About herself. About Hollywood. About success. "I don't believe it... " She stops, fully aware that, at this point, the self-doubt thing might be a little cloying. "It is not attractive," she concedes. "It works better, actually, when you are younger. But it's an old friend. I think it came from insecurity and, you know, high expectations. But now I'm saddled with it. It's not something I can just slough off. It's so familiar, so homey. And, honestly, I can't lie about how I feel."

"Diane totally accepts herself and totally insists that others accept her as herself," says her buddy Steve Martin. "And yet she's vulnerable. One day she was complaining, just ranting and raving, when suddenly she just said, 'You know, I'm glad I'm an oddnick.'"

Packing up her teapot, Keaton gets ready to take off for an acting lesson. "This is my life," she tells me. "If someone says it's not the norm, that doesn't bother me. When you're younger, you think one way must be right. But I don't feel that way anymore."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now