Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

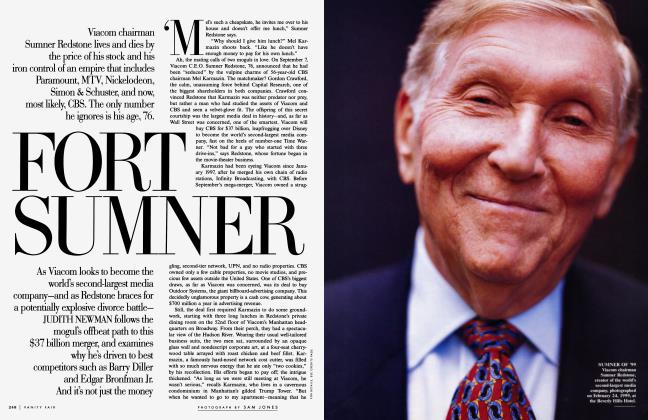

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHUNDER IN THE BLACK MOUNTAINS

Tiny, fierce, its unconquerable mountains roamed by wolves, Montenegro has been the last republic willing to remain part of Slobodan Milošević's demented "Greater Serbia." And now it, too, craves freedom. If the NATO powers keep dithering, stand by for a grim coda to Bosnia and Kosovo

Christopher Hitchens

I suppose," I said, gesturing in a politeconversational manner at the fabulous escarpment of peaks that rose behind us, "that it's the mountains that have made Montenegro unconquerable." The priest with whom I was lunching lowered his piece of freshkilled lamb. "No," he admonished me emphatically. "It is a site only for the eroticism of the wolves." There is true power in really good bad English, and I was halfway to getting the point but perhaps looking baffled, because the priest decided to throw euphemism to the winds. "For the fucking of the wolves, with the other wolves. Only for this." In other words, he was saying, nobody really wants to conquer Montenegro. It's the place that god forgot, the end of the earth, a wasteland of violence and poverty given over to lupine copulation. (I later learned that in the local vernacular there is actually a word— vukojebina—which is used pungently to denote the location of a wolves' motel.)

This is deep Balkans: a den of banditry and haunt of clans, with a "black" economy conjured from smuggling and extortion. If I had been told, of our delicious if basic lunch, that it was black lamb slaughtered by gray falcon, I would have been inclined to believe it. The "Black Mountain." Crna Gora. Montenegro. In whatever language you render it, the very name has a slightly Ruritanian ring (and the goings-on at the old Montenegrin court in fact inspired Franz Lehar to write The Merry Widow). But between the grimness and tragedy, and the operetta-scale farce, is being written the likely final chapter in the whole demented project of Greater Serbia. The final fratricide of the Milosevic wars will probably take place here, the endgame of a halfdiseased and half-romantic national frenzy.

Ten years ago, there were six republics within federal Yugoslavia. Two of them— Slovenia and Croatia—split away as soon as they could, suffering light and heavy bombardment respectively from the Serbdominated Yugoslav army (J.N.A.). Macedonia and Bosnia followed suit, with catastrophic consequences for the latter. Only Montenegro decided voluntarily to stay with Serbia, and to lend a drapery of illusion to the existence of a "Federal Republic of Yugoslavia"—the nightmare state of which Slobodan Milosevic is still the "president." Montenegrins are close kin to Serbs and have a shared history of arduous and bitter resistance to the Turks, and to Islam. It was Montenegrin forces who were noticeable and aggressive in the hellish shelling and looting of the ancient Dalmatian city of Dubrovnik in 1991. It was a psychotic Montenegrin extremist—the failed shrink Radovan Karadzic, now wanted for war crimes—who acted as Milosevic's surrogate leader in Bosnia. Milosevic's own father was from Montenegro. The current "prime minister" Of TUmp YllgO slavia, Momir Bulatovic, is a Montenegrin. For practical purposes, Montenegro has been Serbia's jackal over the past 10 years. But now, and against all expectations, a probable majority of Montenegrins want out of Yugoslavia and an end to Milosevic's rule. It is as if Austria, having united with Germany in the Anschluss of 1938, had opted to reclaim its independence in 1944. the harsh title given by the heroic Yugoslav dissident Milovan Djilas to his 1958 memoir of a Montenegrin childhood and youth. But it can be a mistake to stress only the bleak history of blood feuds and "ancient hatreds." The rocky interior of Montenegro, it is true, is arid and pitiless and impoverished, and enlivened chiefly by amorous yelpings from the wolf population. But on the coast around the luminous Gulf of Kotor there are gemlike cities that once paid allegiance to Venice, with gorgeous Catholic and Orthodox churches existing in amity. (The little town of Perast, a sort of micro-Venice complete with campanile and its own pair of miniature islands, is one of the most exquisite as well as one of the most friendly places in which I have ever set foot. It was there that I casually mentioned to a complete stranger the absence of any pictures of President Slobbo. "Milosevic—son of a whore!" was his immediate reply: the better for being uttered in the Italian slang figlio di puttana that you often encounter along this coast. Out on the crystalline Adriatic water, a Serbo-Yugoslav gunboat provided a floating reminder of who is still in charge, as well as of the fact that Montenegro, for now, is Serbia's only coastline.) Then, after a journey up through the heartbreaking ranges, you can come to the cool and elegant antique royal capital of Cetinje. Here, amid the lime trees and wide walking streets and little piazzas, you can find a moment of old Europe as if preserved in aspic or amber. Before 1914, Montenegro was an independent kingdom. To this day Cetinje boasts, whether locked and shuttered or sometimes transformed into arts schools or music rooms, the former embassies and legations of AustriaHungary, imperial Russia, and all the other powers that came to ruin in 1914. I happened to be there on the fourth of August, the 85th anniversary of the British Empire's declaration of war on Germany, and paid a call on the building where a plaque announced HIS MAJESTY'S LEGATION. The faded old villa-cum-mansion now did duty as a conservatoire. But though I spent a long moment looking back through the looking glass at the lost world of pre-deluge Europe, I had come on exactly the right day to look forward— to the day when Montenegro will ask for its independence to be restored, and recognized again.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 118

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 111

Land Without Justice was

On his visit to Cetinje in 1929, Evelyn Waugh played up the Ruritanian angle strongly, mocking the tiny Parliament building for having been "the legislature by day and the theater by night." He also stressed the Corsican and Sicilian ethic, noting the number of daggers and pistols for sale and dryly suggesting: "Most likely the owners were saving up to buy cartridges for a stolen army rifle, and so snipe the neighbors in a more deadly manner from behind their pig-styes." The man I had come to meet could have represented, at First glance, either the comical or the sinister side of this caricature. He was understood to be "close" to the independence-minded young president of Montenegro, the 37-year-old Milo Djukanovic. But he held no formal position and he wouldn't be quoted by name. He also looked—though I had heard him described as a "spin doctor"—as if he had spent a night in the open in an especially louche vukojebina. "Wolfish" was a word that leapt immediately to mind. The experience was much more like an encounter with a watchful dissident than one with the unofficial spokesman of a government. However, he turned out to speak with passion and authority, and everything he predicted to me came true, so I am glad that I took so many notes as we lowered our questing muzzles into the slivovitz.

"The Fascist idea of 'Greater Serbia' is now dead," he announced without preliminaries. "It is impossible without the nucleus of Montenegro." He was himself, he said, a fullblooded Serb (a number of Montenegrins announce themselves as such) but a Montenegrin patriot First and foremost. "And since 150,000 Montenegrins also live in Serbia, our very existence is an argument for dissolving Yugoslavia and replacing it with a confederation." (This might sound like a contradiction, but bear in mind my analogy above of Austrian nationalism as opposed to German supernationalism.)

There were free elections in Montenegro last year, which the anti-Milosevic forces won in spite of intimidation from armed pro-Belgrade elements. So, said my friend, "Milosevic can never be president here again. Nor does he control any local ethnic forces who could help him try his usual tactic of racial partition." Then he told me what was going to happen. "In two or three days, the Montenegrin government will make a series of demands to Belgrade. We will ask for the name Yugoslavia to be scrapped and replaced by 'Commonwealth of Serbia and Montenegro.' We will ask for full control over all our armed forces, and for complete economic independence. We shall also propose a onechamber parliament with equal rights for Montenegro, and a distinct and convertible Montenegrin currency." I put the most obvious question: What if Milosevic refuses this amputation of his authority? "In that case we will hold a referendum on full independence, no sooner or later than next year." A day later, the Montenegrin authorities did make precisely this series of demands, tightening up the last point a bit by giving Milosevic only six weeks to reply and announcing that if he responded in the negative there would be a referendum on complete independence this fall.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 126

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 118

Some people think that President Milo Djukanovic is bluffing. But I would not be so sure. As a former Milosevic protege and well-tailored leader of the Communist uth, he has seen the dank and desperate Serbdominated leadership from the inside and has come to appreciate that Montenegro is now shackled to a corpse. On the streets of his capital, and at airports and border posts, he is daily reminded that Montenegro cannot long endure half Serb and half free. The military is controlled from Belgrade, while the local police and militia are loyal to him. A volatile situation of "dual power" obtains. Several examples illustrate the point. During the Kosovo war, Belgrade attempted to establish martial law in Montenegro, and called up young Montenegrins to fight. The local authorities ignored the draft law, and Dragan Soc, the minister of justice, who received his own call-up papers, walked defiantly past the military court each morning on his way to work, giving a disrespectful salute. Djukanovic invited members of the Muslim and Albanian minorities into his Cabinet, and allowed 70,000 Kosovo refugees onto Montenegrin soil. Not content with this snub to Milosevic, he permitted leading Serb dissidents to take refuge in his autonomous republic, and permitted the circulation of anti-Milosevic leaflets and magazines, many of which found their way back to Belgrade.

'A bove all," I was told determinedly by the audacious Milka Tadic at the offlees of Monitor, the leading magazine of the democratic opposition, "above all, and for the first time, Montenegro refused to fight in a Serbian war. We helped [Milosevic] in Bosnia and Croatia, but these latest massacres are all his own, and for the first time our people were not shielded by the state from knowing all about them. Everyone can see what a horrible crime it was—if only because they were not involved." Now, she said with a triumphant smile, Montenegro has recognized the international court at The Hague, and has promised to cooperate with it. "So, can you imagine a 'federal republic' where the president cannot pay a visit to the sister republic, because he would have to be arrested and deported to stand trial for war crimes?" The offices of Monitor were bombed twice by pro-Milosevic thugs during the Bosnian war: I can tell she had waited a long time for the chance to say this. And no, she said with a shrug, it's not dangerous to speak that way, or "not anymore."

Ms. Tadic, editor of Monitor, is not in the least like a wolf. She's more like a fox. And she's tall. Montenegrins are extremely tall—to my eye the tallest people in Europe. Taller than the Danes. I met Tadic in Podgorica, the relatively hideous and sprawling and purpose-built capital city that was once Titograd. But one reason the old ex-capital of Cetinje had seemed such a miniature was that its inhabitants gave me the impression that they were walking around on stilts. Since Montenegro has about 650,000 inhabitants, while Serbia boasts 10 million or so, it may be a huge psychological advantage to be able to call on so many lofty people, with such a long martial tradition. (Down on the coast is the homeland of antiquity's Illyrian warrior queen, Teuta. Teuta is a favorite birth name for Albanian girl babies.)

As I write, Milosevic has not personally replied to the Montenegrin demarche, His chief political henchman, the ultrachauvinist Vojislav Seselj, is, however, making blood-and-thunder speeches, saying that the J.N.A. will intervene by force in Montenegro "like the Americans would if California tries to go away." Mr. Seselj's Chetnik militia has never lost a battle against civilians and was involved in some of the foulest work in Bosnia and Kosovo. I wonder, though, how it would acquit itself in battle against tough Montenegrins who are kith and kin. The talk in cafes and bars in Podgorica is just the sort of hushed conversation one used to hear in the banana republics of Central America, revolving eternally around the question "Which way will the army go?" Milosevic keeps his Second Army in Montenegro, and its commanding officers are loyal to him as far as anyone can tell. But the mid-level of the officer corps is thought to contain many who are sympathetic to independence, or are unwilling to risk another dustup with NATO, or are just leery of being the last man killed in defense of an obviously doomed regime. During the Kosovo war, Montenegrin forces stood off Milosevic's soldiers in a confrontation over Kosovar refugees, and this test of wills was as heady as it was novel. Just as one cannot make a child grow smaller, so the momentum and appetite for autonomy increase with the experience of it.

The talk in cafés and bars in Podgorica revolves eternally around the question "Which way will the army go?"

President Milo Djukanovic is daily reminded that Montenegro cannot long endure half Serb and half free.

ontenegro is in an advanced and hectic stage of being a little bit pregnant. u can see it in the emerging battle of the colors: green, red, black, and white— the Montenegrin rainbow. Montenegro lost its independence in the First World War by impulsively siding with Serbia, by suffering Austro-Hungarian occupation as a result, and then by submitting to a 1918 plebiscite on joining the new kingdom of Jugoslavia. In fact, it was the only state on the Allied side in 1914 that went on to lose its independence at the end of the war. Serb troops were on hand to make sure that the 1918 plebiscite went the right way. Those who opposed the Anschluss had to mark ballot papers in green, and have ever since been known as zelenasi, or "the greens." The pro-Serb elements were white, or bjelasi, when white was the Russian shade for counterrevolution. Today, when you see a spray-paint slogan supporting Milo Djukanovic, it will be lettered in vivid green, even though he and his rivals both used to prefer red. Montenegro was the reddest of the old Jugoslav republics: solid fer the wartime Communist partisans and with a very high proportion of party members until the very end of Titoism. Now, however, pro-Belgrade slogans tend to be scrawled in black. This is partly the historic color of Fascism—which is apt enough— but also reminds people that the local Orthodox prelate, a thickly furred old hooligan named Amfilohije Radovic, has been a rhapsodic supporter of Serb ethnic cleansing. And, just to clarify matters, green in the Balkans is the traditional color for Muslims—whose mosques have not, in Montenegro, been dynamited and defiled as they have everywhere else that is in range of Greater Serbia's guns.

Anyway, when Milo Djukanovic took his oath of office as Montenegro's president in January of last year, he did so in the ancient former capital of Cetinje and not in the "official" seat of government. So that that old geopolitical cliche—"the family of nations"—may be about to welcome a tiny new member. Did I say welcome? The NATO powers, including the United States, have been very grudging and hesitant about attending the baptism, or even acknowledging the conception and parturition. Pompous noises are made by the State Department about the "territorial integrity" of the former Yugoslavia, as if that bastard and hybrid were being kept alive by anything but a death-support machine. (Milka Tadic said that she'd argued the point with Clinton at the July summit in Sarajevo, and as her eyes flashed and her Amazonian limbs flexed, I wondered for an instant how he'd coped with the real local version of a "strong woman.") Everyone knows why Europe and America are dithering: if Montenegro "goes," then there is no Yugoslavia, and if there is no Yugoslavia, then there is no state for Kosovo to be a legal part of, and there are timorous statesmen who hope that this highly spiced and heavily booby-trapped question does not come up on their watch. But might it not be nice if, just for once, there was a crux in the Balkans that did not take our diplomatic masters completely by surprise? This one has been coming for a long time: coming like Christmas, coming like a heart attack. There's no excuse for being unprepared. When wolves couple, it's dramatic and impressive and the more modest and reticent animals hardly dare peek. A wolf divorce is more seldom seen, but worth some serious attention for all that.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now