Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

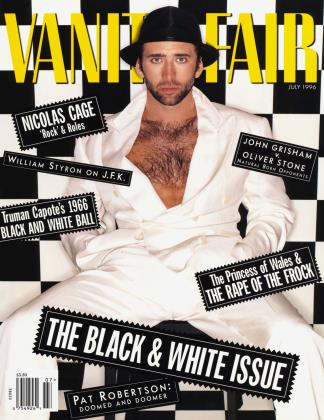

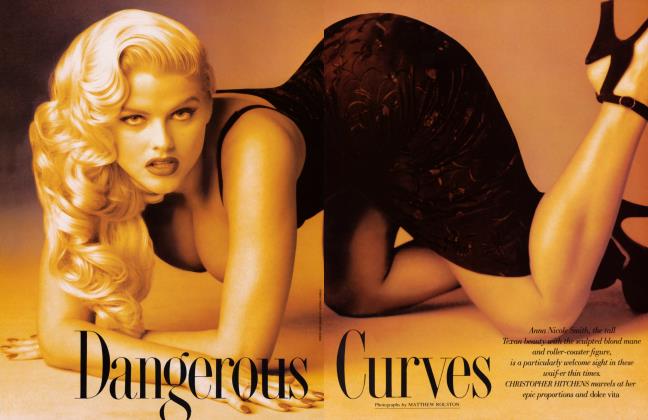

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowCHRISTOPHER HITCHENS ac-cen-tuates the positive—and the negative—of a black-and-white world

July 1996 Christopher HitchensCHRISTOPHER HITCHENS ac-cen-tuates the positive—and the negative—of a black-and-white world

July 1996 Christopher HitchensFor some reason, people have become fond of saying that things aren't black and white, but they are, they are. Nuns and penguins and zebras apart, with their lovely intrinsic contrasts, many things are either deeply black or profoundly white. Anthracite and ebony, snowballs and cocaine. Some felines are jet, some bears are milky—and vice versa. Invited to a black-tie event or a white-tie one, I know where I stand (or, if not, at least whether I've worn the wrong tie). The ace of spades is a decisive card. The white knight clearly announces his intentions. At the beginning and end of our universe, and at its edges and outer limits, black holes and white dwarfs are the unambivalent symbols of the absolute and the infinite. They are possible futures and possible pasts, and they are totally stark. They are not—to employ another common, lazy phrase—shades of gray.

With black and white, you know where you are and (like Laurel and Hardy, like Othello and Desdemona, like Don Quixote and Sancho Panza) you can't have one without the other. The game of chess, with its dance of death and its infinite depth and variety, would be the same game if the squares and pieces were orange and blue. Except that it wouldn't be. We need our black and white.

Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow.

So wrote T. S. Eliot in 1925. Watch the films taken from outer space as the sun rises (and sets) across the terrestrial globe. Or watch the transitions between scenes in Citizen Kane as the sharp edge of shadow transforms the entire perspective. Day and night. Night and day. We need this alternation and, though the whole spectrum of color is involved in it, that spectrum is defined by the presence of black and white—neither of which is a color at all.

In some unexamined but authentic sense, the tones of black and white are the tones of truth and reality. Do not the grainy old documentaries of the Western Front and the Nuremberg rallies and the Depression seem more genuine than yesterday's lurid splashes of color from the TV news? Matthew Brady's photographs of the Civil War, which seem to have a silvery quality about them, hold the attention and the eye much longer than more garish recent spreads from Rwanda or southern Lebanon. So do Edward S. Curtis's immaculately posed Native American chieftains. The blood in Kurosawa's version of Macbeth is actually black, and it looks much more bloody than any crimson or scarlet gore. Who watches a colorized Casablanca without wincing? Sergei Eisenstein in his classic work The Film Sense argues that by avoiding the superficial attractions of color you achieve what both you and the audience want, which is a greater attention to form. Eisenstein was right.

In India and in Japan, and in some other countries and cultures, people wear white at funerals and during periods of mourning. But if it weren't white, don't tell me it would be cerise or canary yellow. In our pathetic way we strive for purity and seriousness, and black and white are the raw materials. When Goya used color, as in his court paintings of the Bourbons, he was a master of the palette and the spectrum and the gorgeous. But when he desired to leave a really vivid impression on the retina, he reached for the charcoal. When Picasso strove for the Goya effect and executed his masterpiece Guernica, he ensured that it was completely and utterly colorless.

Henri Cartier-Bresson and Richard Avedon are alike in this—color is for commercial work, but black-and-white is for the realist study and the attempt at honesty. When Rudyard Kipling aimed to write alternative narratives of the same society and scenery, he chose the title In Black and White. And it's no use being literal and saying that Indians are actually brown. For that matter, ivory is really yellow and so are most "white" piano keys. We know what we are talking about. We don't look at the newspaper or a contract or a confession or a signature of a famous person or a treaty and say, "Here it all is in purple on a yellowing parchment." We satisfy ourselves about the authenticity and we say, "Here it all is—in black and white."

The grainy old documentaries of the Western Front seem more genuine than lurid splashes of color from the TV news.

By convention, in most movies that feature a nuclear explosion, the moment of detonation is captured by the film's going negative. Black and white are abruptly reversed, in an instant of absolute and frightening clarity. (The real-world analogue of this is the unforgettable shadow of that vaporized and vanished human being etched into the pavement in Hiroshima like a photographic silhouette.) Andy Warhol was a master of this affectless technique: the negative as a portrait. But many of these negatives were tributes. And, indeed, you can't have a negative without an implied positive. Cultural nationalists used to complain that our idioms make the very word "black" into a pejorative-blackmail, blackguard, black magic, Black Mischief, and so forth, as compared with the Man on the White Horse and other symbols of virtue. Black, they said, was always associated with darkness and white with light. Actually, it's as easy to find positive usages for black and dark as it is to find negative ones for white. Try black gold for oil, black velvet for a rather satisfying Guinness- and-champagne cocktail, Blackglama for mink, Black Beauty, and the Dark Lady of the sonnets. And what about lily-livered white trash emitting white noise?

In Dalmatia, the rich red wine of the region is locally and with pride referred to as black wine. (There are other regional variations, too: all-black wear is chic in Manhattan; try it in other parts of America and people may think you're in a Johnny Cash look-alike contest.) Henry Ford defiantly said that any color for a car was fine as long as it was black. Norman Mailer was certainly not trying to be unflattering when he postulated The White Negro. Black pearls are the rarest and the most prized. The darker the chocolate, the better the accompaniment to the perfect espresso. You can be as pale as death, as white as a sheet, or have a fish-belly complexion, and wish that you had raven tresses. White is the color of virginity; I leave it to you to determine if that's positive or negative.

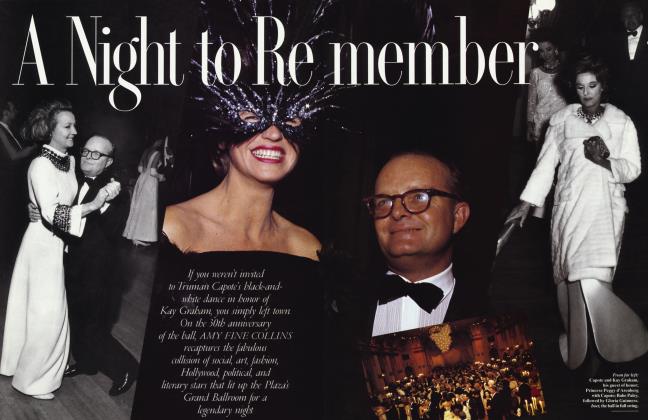

The point, though, is the one that I began with—that black and white are each other's complements, not each other's opposites. This is the artistic point that Truman Capote made so simply with his Black and White Ball, and that Paul McCartney and Stevie Wonder made in a rather more sickly manner with "Ebony and Ivory." Geoffrey Beene and Yves Saint Laurent are not the only designers to have mustered all-black-and-white collections; the elegance of the concept is somehow unmistakable and inescapable and unimprovable at the same time. When Shah Jahan had finished the Taj Mahal as a mausoleum for and monument to his beloved wife Mumtaz, his plan (thwarted by a palace coup) was to build a black marble counterpart for himself, just across the river. It's quite impossible to know this and not to yearn for his intent to have been realized.

When Christopher Isherwood wrote from late-Weimar Berlin, "I am a camera," he was hoping to describe a world of black-and-white objectivity. And perhaps some of that metaphor holds true, since our clearest imagery of good and evil comes from the period of Nazism brought to us by the newsreels of Leni Riefenstahl. (The uniforms of the SS, cloaked Darth Vader-like bodyguard of the regime, were black. The most moving of the German Resistance groups was a team of young martyrs called the White Rose.) But there has also been White Terror and white supremacy. In the end, one abandons these crude categories for that subtle, ironic territory where the two most intense shades commingle. It's known in Italian as chiaroscuro, in French as clair-obscur, and in German (such an expressive language) as Helldunkel. There is an untranslatable Japanese term, iki, which signifies the invisible boundary between dark and light, and which is the essence of the geisha style. Can you tell, if awakened suddenly, whether it is twilight or daybreak? Can you be sure, if you remember your dream, whether you dreamed in black-and-white or color? And this is not to say that life is gray, or crepuscular. Kansas is gray. Oz is Technicolor. The Wicked Witch is black. But then, so is Toto. The rainbow is only a rough guide.

So, on with the show. Bring on Fats Domino. Vive les filles, with their telling boundary between black stocking and white thigh, or the reverse. Bravo to Billie Holliday, who laughed out loud when a member of the band said that she was the cream in their coffee. I celebrate both dusk and dawn as I look back on a shady past and forward to a deeply checkered future.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now