Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowOn the Road, Again

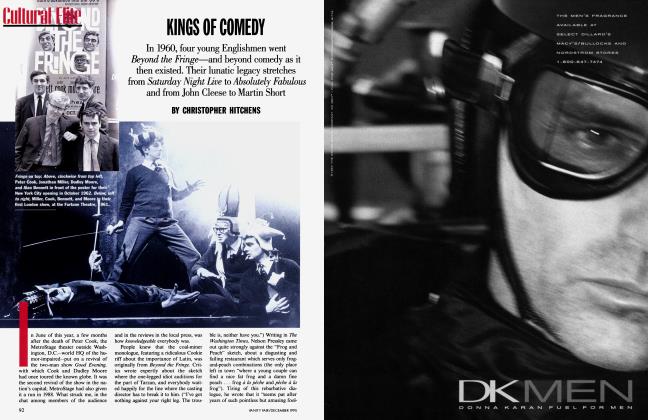

The Beat movement threw a smart bomb into the buttoned-down 50s. Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and their literary and artistic comrades are finally getting renewed respect, JOYCE JOHNSON reports, as the Whitney Museum opens the first major show to document their explosion and Francis Ford Coppola makes plans to film On the Road

JOYCE JOHNSON

ong ago, in the era of Togetherness and the Cold War, when there were no N.E.A. grants or HH teaching jobs for writers and no publisher dared to give Jack Kerouac a contract, the novelist lay down one night in his sleeping bag and dreamed about a literary conference devoted to the work ' of the Beat Generation. Before Kerouac became notorious overnight in 1957 with the publication of On the Road, "Beat" was just a code word meaningful only to his small circle of obscure young male writers. It connoted "a feeling of being reduced to the bedrock of consciousness" as well as beatitude. In his peripatetic search for ecstasy and self-knowledge, in his willingness to live at high speed with no ties and no safety net, the penniless and often homeless Kerouac was its exemplar.

This past June, a three-day conference at New York University went beyond Kerouac's dream when scholars and aficionados gathered to discuss his work alone. Although William Burroughs, the 81-yearold author of Naked Lunch, did not make the trip from Lawrence, Kansas, the featured speakers included other legendary progenitors of the Beat Generation: the poets Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti; the composer David Amram, who wrote the score for the Robert Frank-Jack Kerouac film, Pull My Daisy; and three younger writers whom Kerouac influenced, Diane DiPrima, Ed Sanders, and Anne Waldman.

Critics have vociferously attempted to deny trie Beats entree into the literary pantheon.

About 400 conferees took a walking tour of the neighborhoods where Jack had hung out with the hipsters who became his characters. (The tour included the spot on MacDougal Street where Jack had posed one day in 1957 with me, his black-sweatered 21-yearold girlfriend, for a photo used in 1993 by the Gap to advertise khakis. As the conference brochure noted, I had been airbrushed out.)

Jack admired Balzac's Comedie Humaine, but he could never have imagined that the acrimony over his own literary estate, originally left to his mother, would develop into a tangled plot of Balzacian proportions, with Jan Kerouac, the daughter he met only twice in his life, suing the relatives of his third wife, the late Stella Sampas, for control of his papers and copyrights. The dispute boiled over into the opening N.Y.U. panel, when Jan Kerouac and Gerald Nicosia, a Kerouac biographer, interrupted the proceedings to accuse the Sampases of destroying the Kerouac archive by selling Jack's papers piecemeal to the highest bidders. An ailing Allen Ginsberg magisterially admonished the audience to focus only upon Kerouac's poetry: "Do not be distracted by arguments over lifestyle." Meanwhile, outside, a group of Lower East Side poets who call themselves the Unbearables picketed the proceedings, carrying signs that read, YOU SHELL OUT WHILE THE BEATS SELL OUT.

Ever since the emergence of the Beat writers, one group or another—35 years ago it was conservative critics such as Norman Podhoretz and Diana Trilling—has vociferously attempted to deny them entree into the literary pantheon. That their detractors now include poets who claim they are more anti-Establishment than the Beats is perhaps one of the signs that Kerouac, Ginsberg, and Burroughs may at last be on their way toward acceptance in America as classic writers. They have had that status almost everywhere else in the world for decades.

Continued on page 292

'Beat" connoted "a feeling of being reduced to the bedrock of consciousness" as well as beatitude.

Continued from page 276

erouac is honored in his birthplace, Lowell, Massachusetts, with a monument and a commemorative festival held every October, but most cultural arbiters remain reluctant to give him his due. Back in 1969, when Kerouac was broke again and living in Saint Petersburg, Florida, only one thing gave him any cause for hope: the possibility that his agent, Sterling Lord, would sell the Film rights to On the Road. Although there were negotiations with a producer the very day Kerouac suffered a fatal hemorrhage, there was no option until 1978. After nearly two decades of postponements, Francis Ford Coppola, who has the rights, may finally put the film into production next year, with his son Roman as the director.

For the generation that came of age in the buttoned-down 50s, On the Road was a bible, sending many upon their own quests for unbounded freedom and spiritual enlightenment. Kerouac saw it as the book that inaugurated his creative breakthrough into "wild prose" during the three weeks in 1951 when he found the way to tap into an uninterrupted flow of memory and language as he typed the entire novel single-spaced on a scroll of sheets of drawing paper Scotchtaped together. In 1957, Truman Capote dismissed the work as mere "typewriting." Last summer, the original scroll, which had been stored in a safe in Sterling Lord's office, was put on display in the New York Public Library. This month, when the Whitney Museum opens the first major exhibition to examine the wide-ranging impact of the Beat movement on American culture, the scroll will be one of the main attractions, along with seminal manuscripts by Ginsberg, Burroughs, and Corso. The show will focus not only on Beat writings between 1950 and 1965 but also on the art and music generated by the convergence of underground artists (including Franz Kline, John Chamberlain, and Larry Rivers) who flocked to downtown Manhattan and San Francisco's North Beach and created a vital oppositional movement which flourished independently of Establishment acceptance and support during the bland, conservative years that preceded the explosion of the counterculture.

Could it ever happen again? At a moment when there is so much official hostility directed toward the arts, this is the question that embattled young writers and artists have been asking with more and more urgency.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now