Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIn January 1957, dead broke and womanless, Jack Kerouac took the suggestion of his friend Allen Ginsberg and called a 21-year-old girl he'd never met. That night he moved into her tiny apartment on West 113th Street in New York. Unearthing letters from their bittersweet two-year love affair, which, was broken up by Kerouac's restless wanderings, Joyce Johnson recalls the groundbreaking publication of On the Road, the tempest of publicity and alcohol that followed, and the end of her romance with the troubled king of the Beats

June 2000 Joyce JohnsonIn January 1957, dead broke and womanless, Jack Kerouac took the suggestion of his friend Allen Ginsberg and called a 21-year-old girl he'd never met. That night he moved into her tiny apartment on West 113th Street in New York. Unearthing letters from their bittersweet two-year love affair, which, was broken up by Kerouac's restless wanderings, Joyce Johnson recalls the groundbreaking publication of On the Road, the tempest of publicity and alcohol that followed, and the end of her romance with the troubled king of the Beats

June 2000 Joyce JohnsonIt began with a blind date one January night in 1957. I was visiting my friend Elise Cowen in her railroad flat in Yorkville, where Allen Ginsberg and his lover, Peter Orlovsky, were staying, when the phone rang. Allen said, “There’s someone who wants to speak to you.” It was Jack Kerouac in a phone booth in Greenwich Village, back in town after a visit to his mother in Florida. His girlfriend, Helen Weaver, had recently kicked him out, and he was staying in a run-down hotel on Eighth Street.

The voice at the other end of the line was surprisingly diffident. Allen had told him I was “nice,” and he’d like to meet me—right away, in fact. If I’d come down to the Howard Johnson’s in the Village, he’d be waiting for me at the lunch counter in a red-and-black checked flannel shirt.

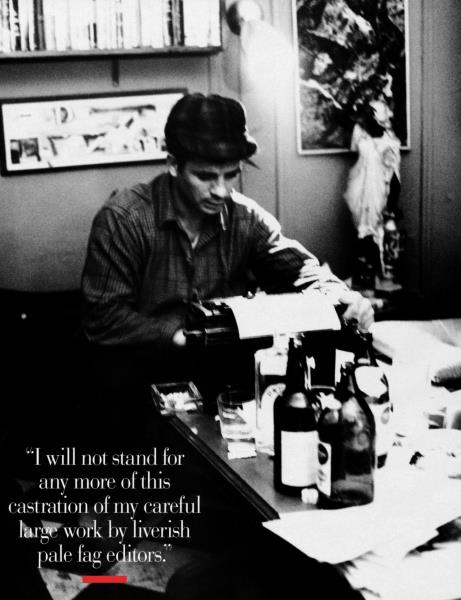

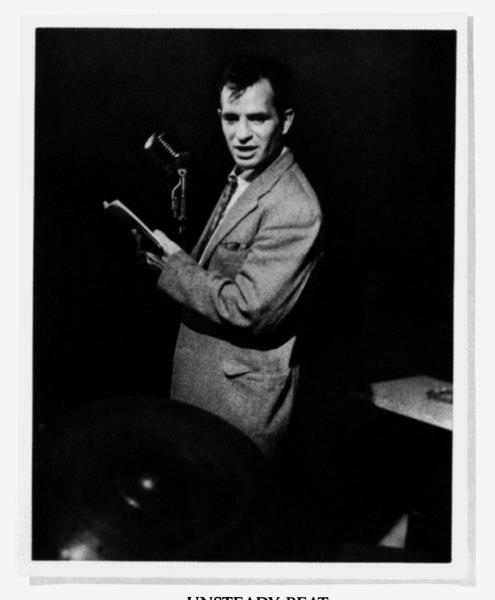

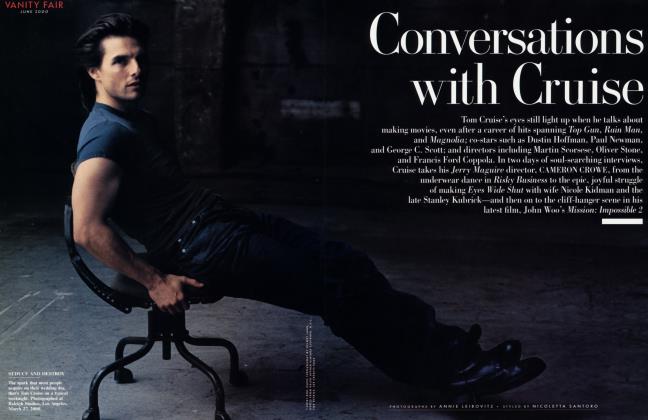

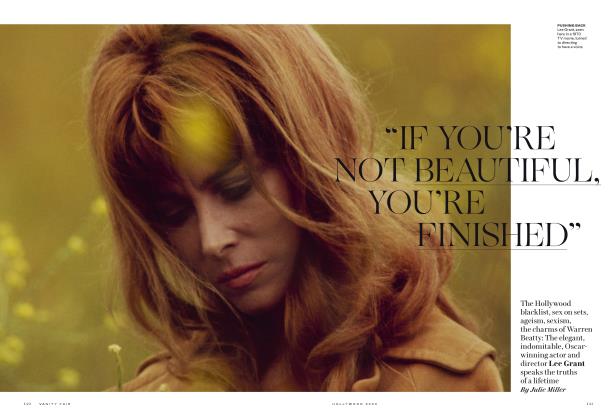

Kerouac at work in 1959, in the Greenwich Village apartment of Fred W. McDarrah, who took the picture.

Kerouac at work in 1959, in the Greenwich Village apartment of Fred W. McDarrah, who took the picture.

“I will not stand for any more of this castration of my careful large work by liverish pale fag editors”

Forty years later, after Allen’s sudden death, I found myself wondering what had prompted him to bring Jack and me together. My friendship with Allen went all the way back to when I had met him at 16 in an apartment near Columbia University where I had no business being, but I had never asked him this question. I decided that a characteristic Ginsbergian mixture of kindliness, practicality, and erotic mischief had probably been at work. Allen was always taking care of people, looking out for his friends. Nine months before the publication of On the Road, Jack was womanless and dead broke. I was a girl with a reasonably hip outlook, who must have seemed at loose ends, with no current steady boyfriend, and—an important consideration from Allen’s point of view—I had an apartment. Whatever ultimately happened between Jack and this girl Joyce, maybe they’d dig each other for a while, have some interesting, illuminating moments.

With no second thoughts, I rushed downtown to meet Kerouac, who at 34 was one of the most compelling-looking men I’d ever seen, with his black hair, blue eyes, and ruddy complexion. Very shyly I confessed to him that I was a writer, too. After an hour or so of conversation, when Jack asked whether he could come home with me, I answered with deceptive coolness, “If you wish.” ung women were not supposed to have such adventures in 1957.

Those were the days when copies of Henry Miller’s novels I and the unexpurgated Lady Chatterley’s Lover had to be I smuggled in from abroad. One reason Kerouac was pracI tically destitute was that since 1950 no one had dared to publish his books. On the Road—its final draft written in one extraordinary burst of creative energy—had sat in the offices of Viking Press for at least four bitter years, and it was not until January 1957 that the hesitant publisher felt the climate was right to give Jack a contract for it.

Circumstances brought Kerouac and me together at a crucial moment. In the bland and sinister 1950s there were thousands like me—women as well as men—young people with longings we couldn’t yet articulate bottled up inside us. Ginsberg and Kerouac would give powerful, irresistible voices to these subversive longings; they’d release us from our weirdness, our isolation, tell us we were not alone.

Jack and I were together for a year and 10 months, though “together” is probably not the precise word to use. Jack would come and go in my life, turning up for a few weeks or perhaps a month, and each time he left I was never sure I’d see him again. Off he’d go in search of the solution a new destination seemed to offer.

At 21 and 22, I was much less experienced than I imagined. I’d grown up in a household without alcohol, except for the bottle of Manischewitz that appeared on the table at Passover. I worried terribly about Jack’s drinking, but made the mistake of thinking he could control it if only he could find a home somewhere—a home that would include a woman, of course. The night I met him at Howard Johnson’s, he told me he had recently spent 70 days in solitude as a fire lookout on Desolation Peak in Washington. He did not tell me he had tried to live without alcohol and had almost cracked up there. In fact, he still clung to the idea that he could solve everything if he wanted to by retreating to a shack in the woods and becoming a hermit. It was a long while before it became clear to me that he had reached a stage in his agony where he could neither be alone nor be with people, much less sustain a love affair.

The night we met, Jack couldn’t even afford to buy me a cup of coffee—his last twenty had vanished earlier that day when he’d bought a pack of cigarettes and received change for a five— so I treated him to a hot dog and baked beans. We exchanged our first kiss as soon as we were inside my apartment. “I don’t like blondes,” Jack warned me, coming up for air, but I didn’t take this as seriously as I should have.

I was living at the time in two furnished rooms on the ground floor of a brownstone on 113th Street, between Broadway and Amsterdam. My weeks with Jack passed all too quickly, as far as I was concerned, but he had never planned to stick around. William Burroughs was waiting for him in Tangier, ready to show him the manuscript of Naked Lunch, which Jack was going to type up for him, and Allen Ginsberg had already paid for his passage on a freighter.

On February 15, Jack sailed for Africa.

Dear Joyce

Only just got your letter due to slow sloppy mailsystem at the American Legation ... a month late... Allen is arriving here in a few days and we will row out in a boat to meet his ship ... we row often, in the bay ... I take long walks to see the ancient fishermen pulling nets with a slow dance ... there are many dull expatriate characters here I try to avoid mostly ... not too many good vibrations in Tangier and the Arabs very quiet send out no vibrations at all so I spend most of my time musing in my room ... somehow can’t write here but anyway that can wait ... what I’m actually doing is thinking nostalgic thoughts of Frisco ... not too interested in this oldworld scene, as tho I’d seen it before plenty ... anyway in early April I’m off by myself to Paris, the others can join me later, to get cheap garret ... then I try to get a job on freighter work my way back this summer.... Grove Press really pulled a fast one on me and cut the novel subterraneans by 60 per cent of all things and ruined swing of prose so I wrote and called it off... I will not stand for any more of this castration of my careful large work by liverish pale fag editors ... you know my first novel Town and City in original ms. form was 1100 pages and ranked with five of the greatest books ever writ in America (this I believe) but after Harcourt Brace cut it over 50 percent to save paper, and ruined rhythm of sentences, it was like 2 or 3 thousand any-other novels a lil better than average ... so the time has come to put my foot down on this editorial activity....

Write soon, honey.

Love

Jack

At the end of April, I came home from my secretarial job at Farrar, Straus & Cudahy one evening and found a notice from Western Union in my mailbox. When I called the office, a clerk read me a cable from Jack. He was returning to the States, already at sea on the SS Nieuw Amsterdam: could he stay with me?

DOOR WIDE OPEN, I answered in the cable that reached him in the middle of the Atlantic.

Jack didn’t have much to say about Paris the day he rang my doorbell and walked back into my fife with his zipper bag. He’d seen the poet Gregory Corso there, had a lot of trouble finding a place to stay, ended up in a miserable room in a Turkish whorehouse, got fed up with the unfriendly French, and went to London to visit his old prep-school friend Seymour Wyse. He said he’d been homesick for America; he wanted to sit by a kitchen window and eat a bowl of Wheaties.

I’d cleaned the whole apartment, bought daffodils, washed my hair. I told him how great New York had become; I wanted to take him right away to all the downtown places I’d discovered while he was gone—the Cedar Tavern, the Five Spot. I can’t remember whether we went. What I do remember is the painful news Jack gave me: this time he wasn’t going to stay with me more than a week. The woman I was losing him to was Gabrielle Kerouac; it was his mother’s kitchen window that he’d longed for. He was going to pick up Memere in Orlando, Florida, a town that bored him profoundly—just swamps and mosquitoes, he said—and move her all the way to Berkeley, where he planned to rent a small house and settle down with her.

He wanted to five with his mother? Having struggled so hard to get away from mine, I couldn’t believe it. I went into the bathroom to cry, which didn’t fool him a bit.

But later Jack said, “Why don’t you come out to San Francisco, if you want to. You can get your own place there, and then we can see each other all the time.”

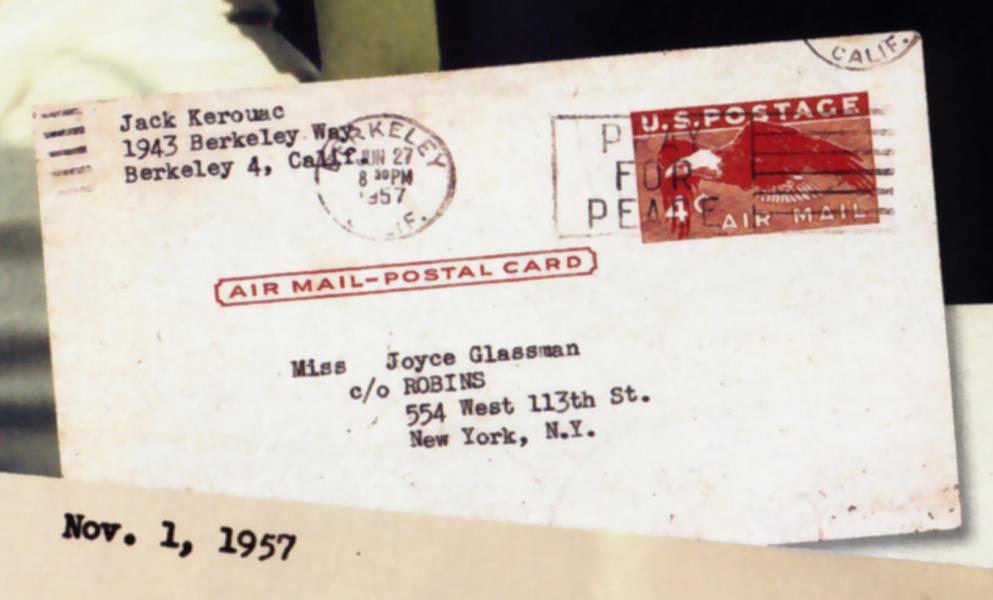

a postcard from Berkeley

a postcard from Berkeley

Dear Joyce

Got your fine letter—Yes, we’ll find you some place to stay in the city when you get here, I’ll meet you at the bus station (or at some pre arranged bar) and I’ll carry your bag and we’ll go find a room maybe where Allen used to live, called Monkey Block, or other places in North Beach, the SF Greenwich Village.... It’ll be a good place to finish your book....

Berkeley is chockful of rooms and apartments, my mother and I found an ideal one in one hour of strolling in the leafy streets. I have a wonderful bedroom with high ceiling and furniture and big double bed, only waiting for my typewriter, books and manuscripts now to complete the scene. At night I pace in my own little yard in the dark....

H W Mustapha Nightaoil King of the Ilte 193? in the age of the Beat New TcTker Dec. 1786th, 19645245 Liseen Jqyce, lcngsiloe because writing new zx)vel which is not mry babe atil, but THE DHARM& BtB, greater than On the Road arI Ix,wever on]y half finished & right in midst of my atarrynight ecstasies contemplating xw to wail & finish it I get big pkxne cafl poopoo fr Sterling Lcrd says Mifletein arrangirg for me to read niyk over mike

I got a letter from my ex-wife who says she wants to settle out of court, wants me to sign a divorce paper merely, so she can get remarried and her new husband will adopt child, and says in writing she doesnt want a cent....

You’ll love it here, it’s great ... there are art museums, beaches, glorious parks, those Chinese restaurants, wharves, waterfront, all kinds of interesting scenes and people, lotsa jazz, friends to make. Just ignore me, my gloom, unless I feel better when you get here.

As ever

Jack

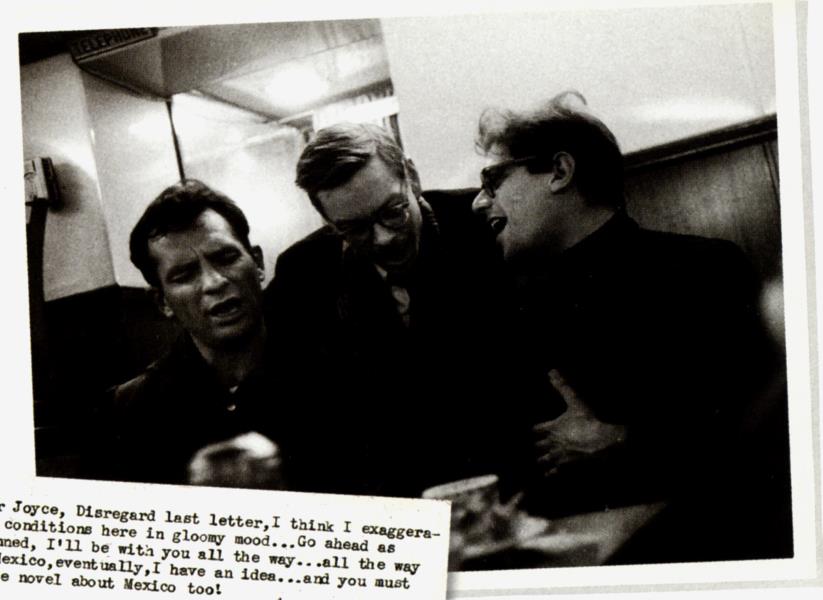

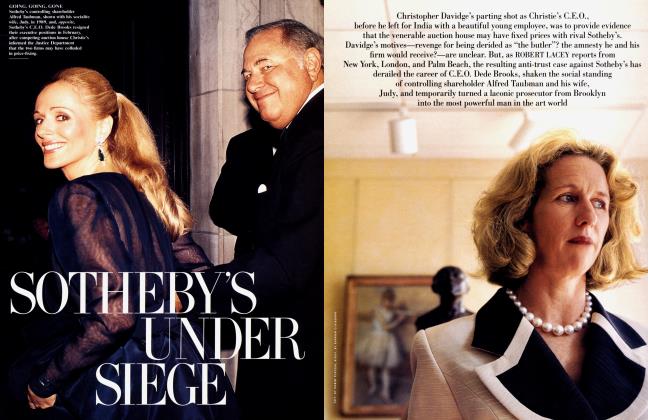

BOYS’ CLUB

BOYS’ CLUB

Kerouac, Lucien Carr, and Allen Ginsberg in a Chinese restaurant in New York, circa 1959.

“Don’t OWN me, and dont be sad because I’m a confirmed bachelor & hermit.”

After receiving Jack’s letter, I began to prepare for my mo mentous journey to the West Coast. In order to econo mize, I gave up my apartment and moved in with a friend, trying to save some money to tide me over in San Francisco until I found a new job there. Before I left New York, I was also hoping to hear from my writing teacher, Hiram Haydn, who was editor in chief at Random House, because I had just sent him the first 50 pages of my novel, having agonized over every sentence in a way Jack would have thoroughly disapproved of.

Dear Joyce,

Pacing up and down my yard yesterday I bethought myself about you ... dont know how to say this so I’ll just say it honestly— (1)1 don’t want you to be disappointed by San Francisco but it’s really nowhere, in the few weeks I’ve been here I’ve been stopped 4 times and my name taken down 4 times for walking in the street after midnight (one time fined $2 for “going thru a red light”) and as you know there’s all this other cop trouble impounding people’s poetry books and God knows what’ll happen to Evergreen Review No. 2 which also has HOWL in it or Gregory [Corso]’s book of poems GASOLINE or anything in this mad silly stupid place which is now a culture for old people on retirement, cops prowling around all night to keep the streets absolutely quiet, in other words to prevent anyone from having fun—In short I am slowly being driven out of California which I loved when I first got here because it was so wild, so end-of-the-landish and has now fallen into the hands of Total Police Authority (God help us if this really spreads back East—in fact I foresee now (unless New York remains too big and wild and ungovernable and I can live there fairly as I please, as of yore) I can foresee being driven out of America altogether and will have to settle in Mexico.) My mother and I have already decided to return to New York, by Xmas, probably as early as October.... Joyce, dont think for a minute that I don’t want to see you, I do, but I cant help it if when you come out here you’ll be in tears of disappointment or just gloom, it’s just awful—Of course we do have our goodtimes like I told you about, wine on the beach, but every time you turn around someone’s gone to jail or in trouble with the cops BECAUSE of innocent things like that, the police have just absolutely got out of hand here.... Here’s what I’m going to do: when ROAD comes out and I get another advance (I hope) I’m moving my mother back to New York, where anyway she can work 2 days a week and support herself completely, and then I’m going to Mexico to make me a pad, Mexico City, and will spend my time, the time of my life, alternating between Mexico City and New York City with occasional visits to this West Coast to see people and camp a little, and if I have the money trips overseas, but I shall never live in California, I can see it now, you dont realize how awful they’ve made it—there’ll be bloodshed around here for sure—Imagine one woman writing in the paper if Jesus Christ was alive he would have led the police to the bookstore to impound HOWL! and all that kind of negative oldwoman attitude all over the place with all these new dreary neat cottages and clean streets with white lines and signs that say WALK, STOP, DONT WALK ... I cant stand it. ... I admit I’m flipping and am bugged everywhere I go but I cant make it here. I wish I hadn’t painted such glowing pictures of this shithouse to you, and made you decide to throw everything up for a lark where you cant lark—But Joyce, if you do insist on coming out here, and get a job, then when I’m ready to leave we can go to Mexico together, that’s why I say we could do that from New York after Xmas, it would be nice to be with you in Mexico City,—if you insist on coming out anyway please dont blame me any more, or by then dont blame me, now you’re forewarned, and maybe you’ll have a better time than I do anyhow. As for that glorious wild Neal [Cassady], the cops long ago took his license because he drives like a human being, or like a young man, instead of like an old man half blind, so he’s completely halted in his activities and we cant afford to see each other_Let me know what you think, study the matter, I’m just warning against a possible mistake that I myself started, damn it. As for seeing YOU, that’s alright with me anytime, because I really like you, you’re a real kid, that is, a true heart.... Thanx for the big interesting letter, write

Jack

(But you decide and you always do what you want DO WHAT YOU WANT)

In July, a few weeks after I received this letter, Random House bought my novel and gave me a $500 advance to finish it. In the meantime, Jack had left San Francisco and moved to Mexico City.

Dear Jack,

Yes, yes, I will come to Mexico! ...

It worries me, Jack, to think of you with $33 to your name while Viking’s machinery works out a way of feeding you. And I’ve really got all this money—so would you like some in the meanwhile? Let me know, and I’ll send you a money order or whatever.

I got a review copy of ON THE ROAD, read it, and think it’s a great, beautiful book. I think you write with the same power and freedom that Dean Moriarty drives a car. Well, it’s terrific, and very moving and affirmative. Don’t know why, but it made me remember Mark Twain. Ed Stringham [a mutual friend, who worked at The New Yorker] has read it too and thinks it “one of the best books since World War II” and is going to write you a long letter and tell you all this, much more coherently than I can....

I remember walking with you at night through the Brooklyn docks and seeing the white steam rising from the ships against the black sky and how beautiful it was and I’d never seen it before—imagine!—but if I’d walked through it with anyone else, I wouldn’t have seen it either, because I wouldn’t have felt safe in what my mother would categorically call “a bad neighborhood,” I would have been thinking “Where’s the subway?” and missed everything. But with you—I felt as though nothing could touch me, and if anything happened, the Hell with it. You don’t know what narrow lives girls have, how few real adventures there are for them; misadventures, yes, like abortions and little men following them in subways, but seldom anything like seeing ships at night. So that’s why we’ve all taken off like this [Elise Cowen had gone to San Francisco], and that’s also part of why I love you.

Take care.

Love,

Joyce

Dear Joyce

The giant earthquake was this morning at 3 am, I woke up with my bed heaving & I knew I wasn’t at sea, but in the dark I’d forgotten where I was except it was in this world & here was the end of the world—I stayed in bed & went back to sleep, figuring if my giant 20-foot ceiling was to fall on my bed, everybody would die inside or outside buildings—It was just like that Atlantic tempest last February, darkness & fury—I could hear sirens wailing & women wailing outdoors but the hush of silence was in my ears, that is, I recognized that all this living & dying & wrath was taking place inside the Diamond Silence of Paradise—twice this year I’ve had the vision forced on me—Well, there wont be another earthquake like this here for another 50 years so come on down, I’m waiting for you—

Dont go to silly Frisco—First place, I have this fine earthquakeproof room for 85c a night for both of us, it’s an Arabic magic room with tiles on the walls & many big round whorehouse sexorgy mirrors (it’s an old 1710 whorehouse, solid with marble floors)—we can sleep on the big clean doublebed, have our private bath (also with 20-foot ceiling & cloistral bas-relief Mohammedan windows)—it’s right downtown, you can enjoy city life to the hilt then when [we] get tired of our Magian inwardness Sultan’s room we can go off to the country & rent a cottage with flowerpots in the window—

—Your money will last 5 times longer & in Frisco you wouldnt be seeing anything new & foreign & strange—Take the plane to Mexico City (bus too long, almost as expensive too), then take a cab to my hotel, knock my door, we’ll be gay friends wandering arm-in-arm in Mexico—Also, we’ll do our writing & cash our checks in big American banks & eat hot soup at market stalls & float on rafts of flowers & dance the rumba in mad joints with 10c beers_I am lonesome for yr. friendship & love, so try to come down, lots to talk about, lots of sleeping & loving, eating & drinking & walking & visiting cathedrals & pyramids & wait till you drink big waterglasses of cold fresh orange juice every morning for 7c!!—& giant T-bone steaks for 85c that you cant finish!—& I’ll show you sights most Americans dont know exist here & you can write a big book—

After this I am going back to N.Y, via Florida, perhaps we can go back together—

At first, I thought I wanted to be alone & stare at the walls, but now I realize, after the earthquake, no one can be alone, even one’s own body is not “alone,” it is a vast aggregate of smaller living units, it is a phantom universe in itself— And maybe I’ve come to realize this now because in this altitude (8000 ft.) I dont get drunk, & I’m not taking drugs any more (my connections are dead), & I just stare healthily at the interesting world—Come on, we’ll be 2 young American writers on a Famous Lark that will be mentioned in our biographies—Write soon as you can, this address, I’ll be waiting for your answer-

Jack XXX

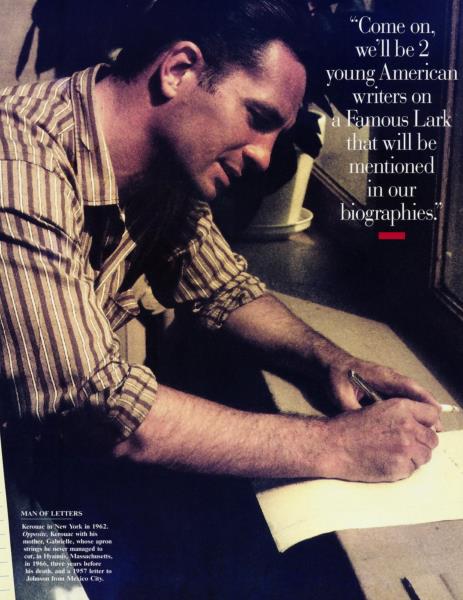

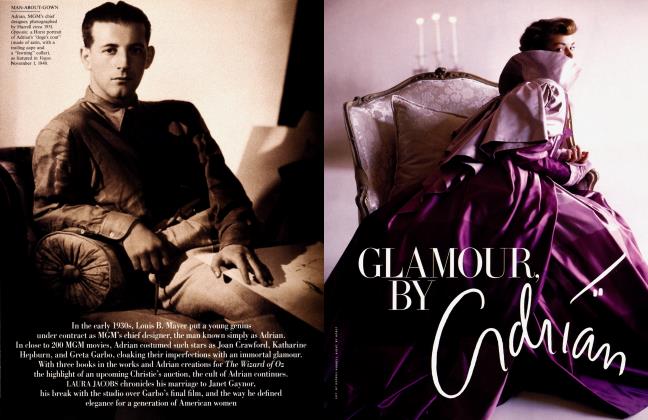

MAN OF LETTERS Kerouac in New York in 1962.

MAN OF LETTERS Kerouac in New York in 1962.

“Come on, we’ll be 2 young American writers on a Famous Lark that will be mentioned in our biographies”

Jack’s invitation was so irresistible that I gave up my job. I had begun to feel very doubtful, in view of Jack’s many changes of mind, that I would actually leave New York, so I had just accepted a promotion at Farrar, Straus & Cudahy. Robert Giroux, who had edited Jack’s first novel, The Town and the City, had asked me to be his assistant, which in 1957 seemed a fantastic step up from being a secretary. Now I had to walk into his office and inform him that, instead, I would be flying down to Mexico City to join Jack and to finish my novel. After I gave Mr. Giroux this news, there was a moment of deep, stunned silence, but then he wished me luck. He also said, “Well, be careful.”

Dear Jack,

Just this minute finished making my plane reservation—so I’ll be seeing you Wednesday morning, August 21, at ten o’clock, in Mexico City. That seems just unbelievable to me. All I need now is smallpox, which I’ll acquire next week. Then—OFF! Okay? ...

Much love,

Joyce

P.S. Much “trade word of mouth” about ON THE ROAD, which is a very healthy thing.

Also—on Sunday in the Times, [editor] Harvey Breit put it first on his list of Fall novels which were going to make people sit up and take notice.

Dear Joyce

I’m having an awful case of Asiatic flu, been in my gloomy room alone for 3 days trying to sweat it out in my sleeping bag with hot toddies and pills—I thought I was going to die there for awhile when I began shaking violently from fever—I had to get up & go out & sip soup—& try to cash checks at uncooperative American Embassy (“Protection Department” indeed)—“It’s against regulations” they tell me dead on my feet & in need of medicine—How I made it I dont know, but I do know I cant get any writing done this trip in Mexico, just a round of bad luck has hexed my visit—God know what’ll happen next—As soon as I can walk without feeling weak I’m taking a bus back to Florida to my home & my room—My neck is swollen up like a bejowled millionaire’s—As soon as I’m home I’ll write to you again and we can decide where we’ll meet— For one thing, I’ll be coming to N.Y. this Fall undoubtedly (business will crop up)—I don’t want you to be confused, this latest “change of mind” I cant help, I’m sick & need care— Will you write to me at Clouser St [the address of his mother in Orlando]?

Jack

On September 4, Jack rang the doorbell of my new brownstone apartment on West 68th Street. At midnight we went out and got The New York Times and found the extraordinary review of On the Road by Gilbert Millstein that immediately established Jack as the avatar of the Beat Generation and one of the most important American writers since Ernest Hemingway. For once, Jack had had some phenomenal luck. Millstein, who had been keenly interested in the Beats ever since John Clellon Holmes’s prophetic 1952 article “This Is the Beat Generation,” happened to be substituting that day for the Times’s regular reviewer Orville Prescott, a conservative gentleman who was away on vacation. Jack would not have become famous overnight if Prescott had reviewed On the Road.

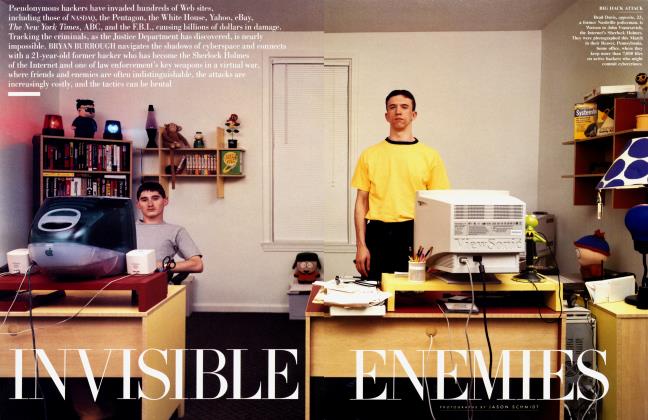

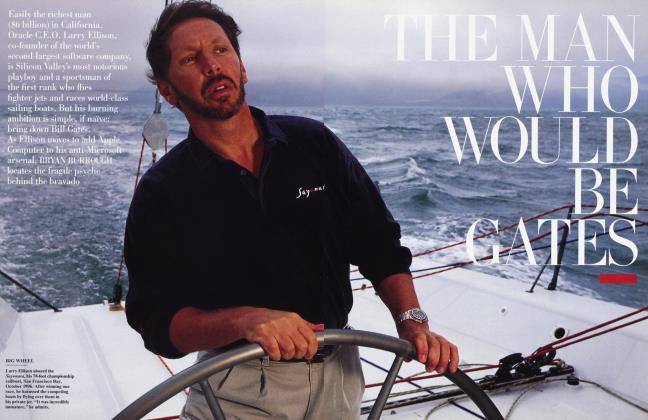

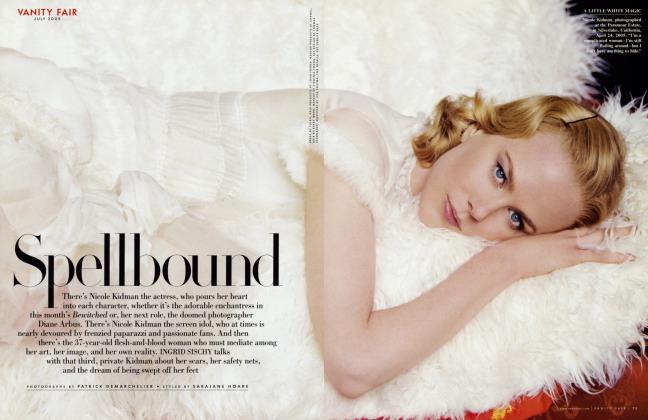

UNSTEADY BEAT

UNSTEADY BEAT

Kerouac onstage during a week of readings at New York’s Village Vanguard, December 1957. Uncomfortable playing the King of the Beatniks, he was drunk at most performances.

Apart from a few reviews, much of the critical attention On the Road received was hostile and humiliating. Just as Jackson Pollock’s groundbreaking paintings had been described as work that could have been done by a chimpanzee, Jack’s true literary achievement—his breakthrough into spontaneous prose—was dismissed by Truman Capote as “typing” and either overlooked or cruelly derided by such critics from the literary establishment as Norman Podhoretz, who accused Jack of wanting to replace civilization with the “street gang.” According to The Hudson Review, Jack wrote like “a slob running a temperature”; the Herald Tribune found him “infantile,” and the Sunday Times reviewer, far less enthusiastic than Millstein, wrote off the Beat Generation as a “sideshow” of “freaks.” By October, with columnist Herb Caen’s invention of the term “Beatnik,” the Beat Generation had been thoroughly trivialized by the mass media and at the same time made available for easy, empty imitation, a phenomenon that Jack found profoundly disturbing.

He coped with his bewildering notoriety by drinking: cheap wine, champagne, cocktails—whatever he could get. I still naively did not think of him as an alcoholic—he just seemed to be going through a particularly difficult time. But I knew he was in danger. On the night of a party Gilbert Millstein gave in Jack’s honor, a few days after his humiliating appearance on the talk show Nightbeat, when he drunkenly told the American public he was waiting for God to show him His face, Jack felt too fearful and depressed to leave the apartment. He told his friend John Clellon Holmes, who came to see him that night, “I don’t know who I am anymore.”

Toward the end of September, Jack almost proposed to me during a weekend away from the stresses of fame in Lucien Carr’s old farmhouse in upstate New York. (Jack had known Carr since 1944, the year he also met Ginsberg and William Burroughs.) Before Jack and Lucien began an all-night session of heavy drinking, we had a memorable dinner featuring the first apple pie I had ever made, which Jack promptly christened “Ecstasy Pie.” “I know we should just stay up here and get married,” he said to me after a walk in the woods the following day. I said, “I know that, too,” and we left it at that. (Jack didn’t marry again until 1966. He had known his third wife, Stella Sampas, since his childhood in Lowell, Massachusetts. She was with him in 1969, when he died in St. Petersburg, Florida.)

Dear Elise [Cowen],

... Jack is here in town now, has been for 2½ weeks—he may leave tomorrow, but may stay another week—the plans keep changing. All the publicity doings in connection with ON THE ROAD bugged him quite a bit. There’ve been a round of parties with vast phalanxes of hand-shaking people who think the Beat Generation is so-o-o fascinating, isn’t it?— everyone pours drinks down him trying to make him live up to the book—and there are lots of eager little girls everywhere who say, “ooh, let’s go to my house for a party” at four o’clock in the morning (they are my pet dislike and I’ve developed quite a sharp tongue, I’m afraid: “Look sister, there isn’t going to be any party,” etc., etc.) Also we’ve met a geeklike radio announcer, an AA member with no insides of his own left who gets his kicks from watching other people, gives Jack goof balls and makes him talk into a tape-recorder—Him I would like to murder! ... Aside from this nonsense—it’s been great seeing Jack again. I dig ironing his shirts, cooking for him, etc. It’s funny—it’s not at all romantic anymore, but it doesn’t matter—I love him, don’t mind playing Mama, since that’s what he seems to want me to be. I may go down to see him in Orlando—I’ve gotten kind of a left-handed backwards invitation (his mother seems to want me to come?). There’s no doubt in my mind anymore that Mama is the villain in the true classic Freudian sense.

Love,

Joyce

Chere Sheila [a Barnard classmate who had been sharing Elise’s apartment and had gone to Paris],

... At this moment, I am sitting in my new sublet apartment, 65 West 68th Street (my most swanky address to date!) and M. Kerouac is fast asleep in the next room—not even the typewriter disturbs him. He came to town [when] ON THE ROAD was published, presumably to stay for a month—but he may go back to Orlando in the next day or so, maybe not. After the first frenzied week we have been trying to live quietly with the receiver off the hook most of the day. He sleeps, broods, eats, stands on his head—I cook, clean, work on my novel—and I like it! Rather—I love him. ON THE ROAD is a great success, looks like a best-seller already—3 editions sold out so far, may be a movie, a musical, etc. But sometimes I think people are really out to kill him—like whispering “doesn’t he drink too much?” and then pouring drinks down him, or saying “oh you must meet soand-so” who turns out to be boring, empty and vicious—and he’s so innocent, can’t play it like a game, but tries to like everybody and worries about whether or not they really like him and if they’ll be hurt if he doesn’t show up at their parties. So maybe he’s better off getting away from New York now— when he first arrived, he was thinking of living here....

Love and write soon,

Joyce

Dear Joycey

Dig my new typewriter! A Royal standard, I’m renting it for $7.73 a month (ug) but if I do buy it they will deduct that from the $89.50 price ... and I think I will buy it cause it’s a bitch, with a good firm fast touch, nice small keys, nice quiet sound, direct keys (unlike my lost typewriter that had indirect jointed keys for the silencer equipment and they tended to jam) ... on this machine I can swing and swing and swing and swing. I think I can go 95 words a minute on this one after a week of practice, as now.... The movers owe me a chick a check for $100 for the lost one ... so I’ll buy it ... and this is such a good typewriter that all I do is yak and yak about nothing interesting.

Now I’ll type up all my poems and prose, which has been lying around in my boxes in hand script—I’ll be curious to see what happens to On the Road this week. Lemme know, I dont get the Times here....

I also bought a roll of white teletype paper that reaches from Orlando Fla. to NYCity ... huge, a dollar forty, I’m all set to go now: also I will type up my final translation of the Vajracheddikaprajnaparamita on a long 12 foot roll and read it like a torah scroll every morning....

I just got Allen Ginsberg’s Guggenheim [Fellowship] form, I have to recommend him, which I’ll do mightily. It’s funny (this is confidential) what he says to them: i.e.

a. Significance of its presumable contribution to arts: Unpredictable

b. Present state of project: Already begun

c. Expectation as to completion: In Time.

d. Places: Europe, Orient, & America

e. Authorities: None

f. Expectation of publication: Promised to City Lights [the San Francisco publishing house co-founded by the Beat poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti]

g. Ultimate purpose as artist: To write an ecstatic poem of spiritual reality.

So there!

He also says: “Worked alone, consulted W. C. Williams and Jack Kerouac on poetry, 1948-1956”

what, I mean wha, I mean, wha?

It pleases me, he never told me I was a poet to my face (hoping I wouldnt get spoiled, I see now)....

Well, Joyce, enuf of this, write as often as you want,

I’ll answer every letter double

As ever,

love,

Jack

Just before he got his new typewriter, Jack in one week had written a play called Beat Generation, which he hoped would be directed for Broadway by Leo Garen, a brash and unreliable 21-year-old whom he had just met. By mid-November, Jack was roaring ahead on the new novel he’d promised Viking.

Hack’

Ho’

Lissen Joyce, longsilence because writing new novel which is not memory babe atll, but THE DHARMA BUMS, greater than On the Road and however only half finished & right in midst of my starrynight ecstasies contemplating how to wail & finish it I get big phone call poopoo from [Kerouac’s literary agent] Sterling Lord says Millstein arranging for me to read my work over mike in Village Vanguard nightclub for salary per week so will do for money and for excuse to come back New York. Will live at Henri [Cru]’s around the corner & sleep all day, also type my new novel on his machine at dusk, then Henri and I dress up and sally forth to my 2 daily performances in the Vanguard. If this doesnt kill me nothing will. Imagine all my friends in the audience. I’ll just be a cool sound musician and act cool, that’s what. But the money is grand and I’ll take it: I wanta buy me a stationwagon and disappear with my rucksack into the West this spring, thats what. Leo [Garen] has tinhorn ideas about the art of the play, his letter betrays that, my play is admittedly too short but outsida that it’s something new & fresh, a SITUATIONLESS PLAY FOR FUTURE PEOPLE. Leo’ll end up producing tinhorn plays for TV, you watch. For money. I’m not money mad, that’s why I’m an artist. I wont write back to Leo. As for Marlon Brando [who had expressed interest in starring in a film version of On the Road], he can go fuck himself. I dont care about these tinhorn show people. What do I care? If I had to go and apply for jobs like you do, they’d have to drag me into Bellevue in two days. I couldnt stand it. That’s why I am and will be always a bum, a dharma bum, a rucksack wanderer_Allen and Greg [Corso] sent me their latest poems from Paris. Greg says “There are old sweetlys in sun-arc! gentle grandninnies” ... and Allen says “O my poor mother with eyes of Ma Rainey dying in an ambulence” ... new pomes_I’m coming to New York for the gentle sweetlys of sun-arc in December and I’ll see you. I’m going to live with Henri because I want to sleep while he works all day and I want to be in the Village and I want to watch his TV and I want to talk with him for a month and I dont want to importune you any further because as I told you I’m an Armenian and I dont wanta get married till I’m 69 and have 69 gentle grandninnies. Please dont be mad at me, I wanta be alone, Greta Garbo. This is going to be the greatest fiasco in history of American Literature, this Village Vanguard shot....

Jack.

Dear Jack,

I’ve read and reread your letter.... What’s happening, Sweetie? I’ve heard you say the things you wrote me before—always when something bad was eating away at you.

I do understand that you need to be alone—and yet not alone, too, I think. But none of that stuff about “importuning,” please. I love you and it makes me very happy to be with you, to fry your particular eggs simply because they’re your eggs—whether I’m your girl, your mistress, your friend, or whatever—those are all words anyway. I love you quite independently of eighty-six gold rings and documents—don’t you understand that, you idiot. So, look—live at Henri’s if you think you have to do that now—but the door is still open always. Jack, I don’t expect anything from you. Don’t be scared of me, please! But I must say I’ve always thought of you as a Frenchman (Jean Louis Kerouac)— don’t think you make a convincing Armenian.

What’s DHARMA BUMS about? ...

Love,

Joyce

When Jack returned to New York in December 1957, he did indeed move in with Henri Cru, who had helped me move into three different places since July and who lately had seemed particularly friendly to me. He was a big, moonfaced man with an enormous protruding belly, who prided himself on his French cooking. When Jack took me to dinner once at Henri’s apartment on West 13th Street, Henri told us that he had spent the whole day making consomme. He became furious when Jack, who was quite drunk, ate little of the feast he had prepared. He always made a great show of being exasperated with Jack’s lack of common sense. They had known each other since 1939. In the early 40s, Henri’s girlfriend, Edie Parker, had fallen for Jack and later married him.

The first week of Jack’s December visit to New York was agonizing for me because I didn’t hear from him, even though he was living right across town. I stayed away from Jack’s evening of poetry and jazz at the Brata Gallery, which everyone I knew was very excited about. And I was too proud to turn up at the Village Vanguard without an invitation. Jack evidently felt much less comfortable there than at the Brata. Some people said his readings were great, but there were rumors that Jack was drunk for every performance and that the Vanguard had canceled the second week of his engagement. I wasn’t surprised. Nothing could have been worse for him than being up on a stage playing the King of the Beatniks night after night. “Harden your heart,” my new friend Hettie Jones advised me. But I couldn’t. When Jack finally called, inviting me to his second-to-last performance, I went, taking a seat at one of the darkest back tables.

After a long drumroll, Jack staggered onstage with his head sunk down onto his chest. Before he got started, he turned his back on the audience of collegiate-looking couples and bopped along to the music, waving a bottle of Thunderbird in the air. Even Zoot Sims and his cool musicians looked embarrassed. When he finally began reading from On the Road, he slurred the words, though there were moments when he connected perfectly with the jazz playing behind him. Tears came to my eyes as I watched the place empty out even before Jack was finished.

Backstage, there was a girl hanging around, of course, a nocturnal apparition all in black with dead-white makeup. I stepped right in front of her and kissed Jack on the lips. He grabbed me by the shoulders and hung on to me. “Get me out of here,” he said.

He and Henri Cru had soon fallen out, so now he was at the Marlton, the sleazy hotel on Eighth Street where he’d been staying when I first met him. He passed out on the lumpy double bed, and I lay wide-awake all night beside him. There was a war going on between pity and love and my anger. In the morning Jack asked me if I’d take him back after his gig at the Vanguard was over.

Sitting at my kitchen table on December 28, he wrote to Allen: “Broke up with Joyce because I wanted to try big sexy brunettes then suddenly saw evil of world and realized Joyce was my angel sister and came back to her.”

We spent a week holed up in my apartment with the phone off the hook. Jack slept a lot and tried valiantly not to drink, and we were soon back to our old closeness. We talked about the future, though not our future together. Jack was convinced New York would destroy him, which meant we couldn’t live together, as I had been secretly hoping. It would be best for him, he thought, to buy a house somewhere on Long Island and live there with his mother.

Dear Joyce

... When I come into NY this Fall I hope you wont get mad at me if I fiddle around with other girlfriends a little, I dont wanta be “Steadies” with anybody, now if this hurts you why?—does Allen get mad when I go visit Joe Blow instead of him? Don’t OWN me, just be my nice little blonde friend and dont be sad because I’m a confirmed bachelor & hermit. Hard to talk about this, I guess you’re sore all over again. Well, if I do fiddle around with other girls, which is really unlikely in a way, you wont know about it. For instance, Robt. [the photographer Robert Frank] says he saw you with another boy in the park and it made me GLAD for you, not jealous. So remember. In fact your salvation is within yourself, in your own essence of mind, it is not to be gotten grasping at external people like me. You know it too, Buddha.

JeanLouis

Dear Jack,

Well, Sweetie, about your last paragraphall I have to say, really, is that it will be lovely to see you again, and that I mean with all my heart. If you walked in this moment, I would leap up and kiss you, even if you hadn’t shaved for two weeks. And no, I don’t want to “own” you (that was never what I wanted)— but if we come together when we both want to do that and we truly swing, then that’s okay, isn’t it? (And I don’t mean it has to be fun, fun, fun all the time—I love you equally when you’re bugged.) But just one word of warning—I am not Allen Ginsberg! I think he’s terrific in his way, but we’re different. And you must learn to be more of a Frenchman and say “Vive la difference!” Also, if you have secrets—please do try to keep them. So ... like, the door’s still the same door, and you have the same key....

Luv,

yer dexed-up frend,

Joyce

Jack had promised he’d come back in the fall, and he did. Though I didn’t bring the subject up, I was painfully aware he had made a number of trips to the city during the summer without seeing me. He never explained his aloofness, he just reappeared in my life, coming in for long, chaotic weekends of endless drinking with his friends, returning to Memere on the Long Island Rail Road, gray-faced and exhausted.

I remember that we saw a lot of Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky and that on one occasion Allen had me telephone his old Columbia classmate Norman Podhoretz, who had been attacking the Beat writers, and invite Podhoretz over for tea with Jack and Allen at Lucien Carr’s apartment, the most respectable venue he could think of. Podhoretz showed up, but there was no rapprochement. He was huffily offended when Jack and Allen offered him marijuana. The tea party ended with Jack profoundly depressed and Allen shouting angrily at Podhoretz, “We’ll get you through your children!” In his 1999 memoir, Podhoretz described me as a “Madame Defarge.”

One day that fall when I was visiting him during one of Jack’s absences, Allen Ginsberg said to me, “u should be patient and stay with Jack. He’ll always have other women, but he’ll always come home and tell you all about it.”

I said, “But I can’t live that way, Allen.”

And I knew I’d spoken the truth.

At a party in 1962, four years after I broke up with Jack, I met a painter named James Johnson. It took us one night to know we wanted to be with each other for good. In December 1963, after we’d been married for almost a year, my husband was killed in a motorcycle accident. Not long afterward, I heard from Jack for the last time. “All you ever wanted,” he said, “was a little pea soup.”

In 1965,1 read Jack’s description of me in Desolation Angels: “An interesting young person, a Jewess, elegant, middleclass sad and looking for something.”

He surprised me and touched me by saying it was “perhaps the best love affair I ever had.”

“In fact she sorta fell in love with me,” Jack wrote, “but that was only because I didn’t impose on her.”

Excerpted from Door Wide Open: A Beat Love Affair in Letters, 1957-1958, by Jack Kerouac and Joyce Johnson, to be published this month by Viking; Kerouac letters © 2000 by the Estate of Stella Kerouac, literary representative John Sampas; Joyce Johnson introduction, letters, and notes © 2000 by Joyce Johnson.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now