Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

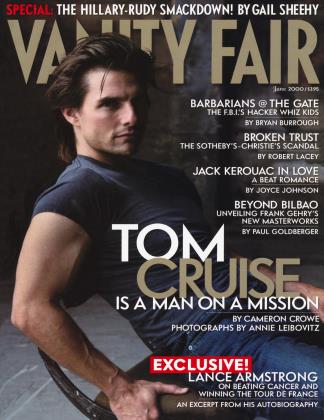

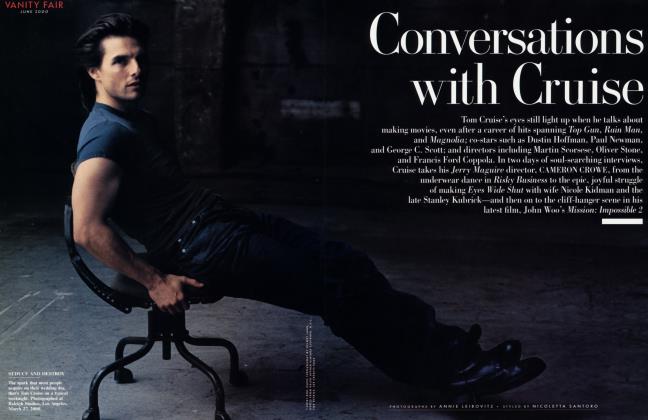

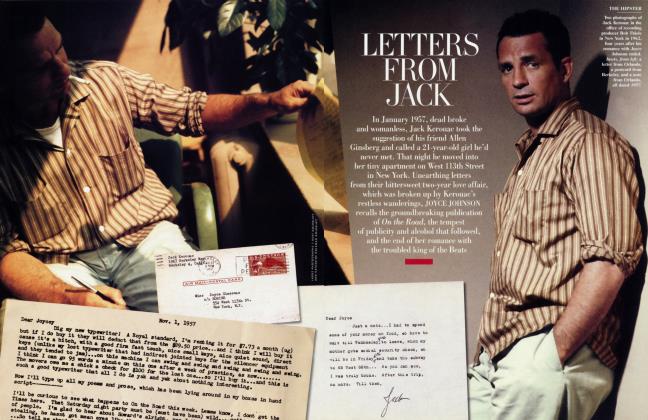

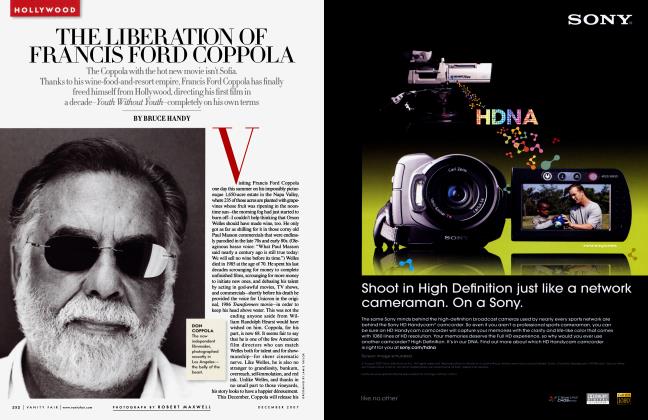

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowIn a candid, tough-minded excerpt from his new memoir, the American cyclist who beat a deadly cancer and went on to win the 1999 Tour de France tells how he quit racing after his recovery, confronted his survival-and then, for three long weeks, found the will to ride harder and faster than anyone else

June 2000 Lance Armstrong, Sally JenkinsIn a candid, tough-minded excerpt from his new memoir, the American cyclist who beat a deadly cancer and went on to win the 1999 Tour de France tells how he quit racing after his recovery, confronted his survival-and then, for three long weeks, found the will to ride harder and faster than anyone else

June 2000 Lance Armstrong, Sally JenkinsLife is long—you hope. But “long” is a relative term: a minute can seem like a month when you’re pedaling uphill, which is why there are few things that seem longer than the Tour de France. How long is it? Long as a freeway guardrail stretching into shimmering, flat-topped oblivion. Long as fields of parched summer hay with no fences in sight. Long as the view of three nations from atop an icy, jagged peak in the Pyrenees.

It would be easy to see the Tour de France as a monumentally inconsequential undertaking: 180 riders cycling almost the entire circumference of France, mountains included, over three weeks in the heat of the summer—a total of 2,290 miles in 1999 (the route varies from year to year). It’s considered the single most grueling sporting event on the face of the earth, and there is no reason to attempt such a feat of idiocy except that some people, which is to say some people like me, have a need to search the depths of their stamina for self-definition. (I’m the guy who can take it.) It’s a contest in purposeless suffering.

Excerpted from It’s Not About the Bike, by Lance Armstrong with Sally Jenkins, to be published this month by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc.; © 2000 by the authors.

But for reasons of my own I think it may be the most gallant athletic endeavor in the world. To me, of course, it’s about living.

A slow death is not for me. I don’t do anything slow, not even breathe. I do everything at a fast cadence—eat fast, sleep fast, talk fast. It makes me crazy when my wife, Kristin, drives our car. She slows down at all the yellow caution lights, while I writhe impatiently in the passenger seat.

“Come on, don’t be a skirt,” I tell her.

“Lance,” she says, “marry a man.”

I’ve spent my whole life racing my bike, from the back roads of Austin, Texas, where I live, to the Champs-Elysees. I always figured if I died an untimely death, it would be because some rancher in his Dodge four-by-four ran me headfirst into a ditch. It could happen, believe me. One minute you’re pedaling along a highway and the next minute, boom, you’re face-down in the dirt.

Getting sick was like that. When I was 25 I learned I had testicular cancer, and was given less than a 40 percent chance of surviving, because the tumors had spread to my lungs and my brain. Frankly, some of my doctors were just being kind when they gave me those odds, and I’ve got the scars to prove it. There’s a puckered wound on my upper chest just above my heart, which is where the catheter for my three months of chemotherapy was implanted. Another scar, left by the surgeons who cut out one of my testicles, runs from the right side of my groin into my upper thigh. But the real prizes are two deep halfmoons in my scalp, as if I was kicked twice in the head by a horse. Those are the leftovers from brain surgery.

I don’t know why I’m still alive. I can only guess. I know I’m a mean adversary. My body is not very habitable, thanks to a fortunate combination of genes and years of hard racing. But I won’t kid you. There are two Lance Armstrongs, pre-cancer and post-. Everybody’s favorite question is “How did cancer change you?” The real question is how didn’t it change me?

There are a few things I should explain here about cycling. It’s an intricate, highly politicized sport, and it’s far more of a team sport than most spectators realize. It has a vocabulary all its own, with words and phrases cobbled together from different languages. It has a peculiar ethic as well. On any team, each rider has a job and is responsible for some aspect of the race. The slower riders are called “domestiques” because they do the less glamorous work of protecting their team leader through the various perils of a stage race—a race that takes place over a number of days. The team leader is the principal cyclist, the rider most capable of sprinting to a finish with 150 miles in his legs. While I started as a domestique, I was gradually groomed for the role of a team leader.

Teammates are critical in cycling. On a severe climb I can save 30 percent of my energy by riding behind a colleague, drafting, hanging on his wheel. Or, on a windy day, my teammates will stay out in front of me, shielding me and cutting in half the amount of work I’d otherwise have to do. Every team needs guys who are sprinters, guys who are climbers, guys willing to do the dirty work. It’s very important to recognize the effort of each person involved—and not to waste it.

The word peloton refers to the massive pack of riders who constitute the main body of the race. To the spectator it seems like a radiant blur, humming as it goes by, but that colorful spectacle is rife with contact, the clashing of handlebars, elbows, and knees. There are constant negotiations between competing riders. For instance, a road is only so wide. Cyclists are always moving around on it, fighting for position, and often the smart and diplomatic thing to do is to let a fellow rider in. If you give a little, you will make a friend, something you might need later. Give an inch, make a friend. Because in the peloton, other riders can also mess you up, just to keep you from winning. There is a term in cycling called “flicking.” It’s a derivative of the German word ficken, and it means to fuck. If you flick somebody in the peloton, it means to screw him, just to get him. There is a lot of flicking in the peloton.

When I first started cycling internationally in 1990—1 was 18—my idea of a race was to leap on and start pedaling. I was called “brash” in those early days, and the tag has followed me ever since, maybe deservedly. I was young and I had a lot to learn, but I wasn’t trying to be a jerk, I was just Texan. The “Toro de Texas,” the press named me. I had my share of results because I was a strong kid, but I was inconsistent. Sometimes I would win, and sometimes I wouldn’t even finish in the top 20. I’ll give you an example: I won the 1993 World Championships when I was 21, becoming the youngest man ever to do so, but by 1995, I still had not completed an entire Tour de France, only stages of it. My reputation was strictly that of a single-day racer; show me the start line and I would win on adrenaline and anger. But the Tour is an event that tends to embarrass youth rather than reward it; it takes years to develop the body and the maturity to endure the hardship.

There is no question in my mind that I would never have won the Tour if I hadn’t gotten cancer. The truth is, it was the best thing that ever happened to me, because it made me a better man, and a better rider. I left my house October 2, 1996, one person, and I came home another, a very sick one. I thought I was going to a fairly routine doctor’s appointment. For several weeks, I’d ignored a painful swelling in my groin, assuming it was just something I had done to myself on the bike. Cyclists are in the business of denying physical pain, so I didn’t pay attention to the fact that I hadn’t felt well for some time. On one occasion I’d coughed up blood. On another I’d gotten a crushing headache and my vision had blurred. But now my testicle was so badly swollen that I couldn’t sit on my bike, and a friend insisted I see a specialist. That day, October 2, my doctors discovered a large tumor in my testicle, as well as a dozen more tumors in my lungs, some the size of golf balls. A week later, they found two lesions in my brain. After surgery, I embarked on four cycles of rigorous chemotherapy. The treatment was so toxic that it literally ate my body away. By the time I finished it on December 13, 1996, I was in the fetal position, retching around the clock, and I’d lost 20 pounds and every muscle I’d ever built up. I’d also lost my million-dollar contract to race with the French cycling team Cofidis, which dumped me. My other sponsors, Nike, Oakley, Giro, and Milton Bradley, remained loyal, but my main living had come from my cycling contract. I had to sell my Porsche, and worried I might lose my house. Everyone assumed I was finished. No one else would sign me. “Come on,” one racing director told my agent. “He’ll never ride with the peloton again.” Finally, a team sponsored by the U.S. Postal Service took me on for a fraction of my old salary—I went from making over a million a year to $215,000, which I called a cancer tax. I began riding again in early 1998. In time, I would discover that the illness had made me a more intelligent man and a more focused rider. But in the beginning my comeback was a disaster.

The Tour is an event that tends to embarrass youth. It takes years to develop the body and the maturity to endure the hardship.

When you have lived for an entire year terrified of dying, you feel like you deserve to spend the rest of your life on permanent vacation. Deep down, I wasn’t ready to go back to work, and the result was that my cycling was fraught with psychological problems. My first pro race in 18 months was the Ruta del Sol, a five-day event through Spain in which I caused a stir by finishing 14th—not bad for a guy recovering from cancer. But I was depressed and uncomfortable. I was used to leading. Two weeks later, I entered Paris-Nice, an arduous eight-day race in notoriously raw weather. On the second day, riding in an icy rain with a crosswind cutting through my clothes, I pulled over to the side of the road and quit. I thought, This is not how I want to spend the rest of my life. “I’m going home,” I told my teammates. “I’m not racing anymore.” I didn’t care if they understood or not.

Back home in Austin, I was a bum. I played golf every day, I water-skied, I drank beer, and I lay on the sofa and channel-surfed.

I went to my favorite Mexican restaurant, Chuy’s, for Tex-Mex, and violated every rule of my training diet. I intended never to deprive myself again; I’d been given a second chance and I was determined to take advantage of it. But it wasn’t fun. It wasn’t lighthearted or free or happy. It was forced.

I was behaving totally out of character, and the reason was survivorship. It was a classic case of “Now what?” I had survived the war against cancer, but I was traumatized. I’d had a job and a life, and then I got sick, and it turned my life upside down, and when I tried to go back to my life I was disoriented. Nothing was the same—and I couldn’t handle it.

I hated the bike.

I was behaving totally out of character, and the reason was survivorship. I had survived cancer, but I was traumatized.

I know now that surviving cancer involved more than just a convalescence of the body. My mind and my soul had to convalesce, too.

No one quite understood that—except for Kristin. Love and cancer were strange companions, but in my case they came along at exactly the same time. I had met Kristin Richard just a month after I finished chemo, at a press conference to announce the launching of my cancer foundation. She was a slim blonde woman who everyone called Kik (pronounced Keek), an account executive for a public-relations firm, who was assigned to help promote the event. I should have known I was in trouble when I kept thinking up reasons to see her that had nothing to do with business. I didn’t know yet if the cancer would come back, or if I’d be able to resume my cycling career. I didn’t know anything. But I knew I loved Kik. Shortly before I returned to Europe to attempt the comeback, I proposed, and Kik quit her job and gave up her house to come with me.

But back in Austin, after several weeks of the golf, the drinking, the Mexican food, she decided it was enough—somebody had to try to get through to me. One morning we were sitting outside on the patio having coffee. I put down my cup and said, “Well, O.K., I’ll see you later. It’s my tee time.”

“Lance,” Kik said, “you need to decide something. You need to decide if you are going to retire for real and be a golfplaying, beer-drinking, Mexican-food-eating slob. If you are, that’s fine. I love you, and I’ll marry you anyway. But I just need to know, so I can get myself together and go back on the street and get a job to support your golfing. Just tell me.

“But if you’re not going to retire, then you need to stop eating and drinking like this and being a bum, and you need to figure it out, because you are deciding by not deciding, and that is so un-Lance. It is just not you. And I’m not quite sure who you are right now. I love you anyway, but you need to figure something out.”

She wasn’t angry as she said it. She was just right: I didn’t really know what I was trying to accomplish, and I was just being a bum. All of a sudden I saw a reflection of myself as a retiree in her eyes, and I didn’t like it.

Normally, nobody could talk to me like that. But she said it almost sweetly, without fighting. Kik knew how stubborn I could be when someone tried to butt heads with me. But as she spoke to me I didn't feel attacked, or de fensive, or hurt, or picked on. I just knew the honest truth when I heard it. It was, in a quietly sarcastic way, a very profound conversation. I stood up from the table.

“O.K.,” I said. “Let me think about it.”

I went to play golf anyway, because I knew Kik didn’t mind that. Golf wasn’t the issue. The issue was finding myself.

I started riding again a week later.

A little history: The first Tour de France was held in 1903, the result of a challenge in the French sporting press issued by the newspaper L’Auto, which later became L’Equipe (The Team). Of the 60 racers who started, only 21 finished, and the event immediately captured the nation. An estimated 100,000 spectators lined the roads into Paris, and there was cheating right from the start: drinks were spiked, and tacks and broken bottles were thrown onto the road by the leaders to sabotage the riders chasing them. Riders in those early years had to carry their own food and equipment, their bikes had just two gears, and they used their feet as brakes. The first mountain stages were introduced in 1910 (along with brakes), when the cyclists rode through the Alps despite the threat of attacks from wild animals.

Today, the race is a marvel of technology. The bikes are so light you can lift them overhead with one hand, and the riders are equipped with computers, heart monitors, and even two-way radios. But the essential test of the race has not changed: who can best survive the hardships and find the strength to keep going? After my personal ordeal, I couldn’t help feeling it was a race I was suited for.

One thing I noticed as the 1999 cycling season began was that I wasn’t quite as good in the one-day races anymore. I was no longer the mad and unsettled young rider I had been. My racing was still intense, but it had become subtler in style and technique, not as visibly aggressive. Something different fueled me now—psychologically, physically, and emotionally—and that something was the Tour de France.

Every member of our Postal team was as committed to the Tour as I was. Besides me, the nine-man roster was as follows: Frankie Andreu was a big, powerful sprinter and our captain, an accomplished veteran who had known me since I was a teenager. At 31, he was the second-oldest rider on our team. Kevin Livingston, 26, was one of our talented young climbing specialists. He’s practically a kid brother to me and one of my best friends in cycling. He often roomed with me on the road and was at the hospital constantly during my cancer treatments. Tyler Hamilton, 28, was our other climber and a rider who is certainly capable of winning a race in his own right. George Hincapie, 26, was the U.S. Pro champion that year and another rangy sprinter like Frankie (he’ll be our team leader during the first half of the 2000 cycling season). Christian Vande Velde, 23, was one of the most talented rookies around; Pascal Derame, 29, Jonathan Vaughters, 25, and Peter Meinert-Nielsen, 33, were loyal domestiques who would ride at high speed for hours without complaint.

The man who shaped us into a team was our director, Johan Bruyneel, 34, a poker-faced Belgian and former Tour rider. Johan knew what was required to win the Tour; he had won stages twice during his own career. In 1993, he won what at the time was the fastest stage in Tour history, and in 1995, he won another when he out0dueled the great Miguel Indurain, who won the Tour five consecutive times, in a spectacular finish into Liege. It was just Johan and Indurain alone at the front, and he sat on Indurain’s wheel the whole way until he pulled around and passed him in the sprint across the line. Johan was a smart, resourceful rider who knew how to beat more powerful competitors, and he brought the same sure sense of strategy to our team.

There was one unforeseen benefit of cancer: it had completely reshaped my body. I now had a much sparer build. In old pictures, I looked like a football player, with my thick neck and big upper body, which had contributed to my bullishness on the bike. But, paradoxically, my strength had held me back in the mountains, because it took so much work to haul that weight uphill. Now I was almost gaunt, and the result was a lightness I’d never felt on the bike before. I was leaner in body and more balanced in spirit.

The doubt about me as a Tour rider was my climbing ability. I could always sprint, but the mountains were my downfall. Eddy Merckx, the legendary Belgian rider who won the Tour five times, had been telling me to slim down for years, and now I understood why. A 5-pound drop was a large weight loss for the mountains—and I had lost 20 pounds. It was all I needed. Training that spring, I became very good in the mountains.

I rode, and I rode, and I rode. I rode as if I had never ridden, punishing my body up and down every hill I could find. There were something like 50 good, arduous climbs around Nice, where Kik and I made our European home. These were solid inclines of 10 miles or more. The trick was not to climb every once in a while, but to climb repeatedly. I would do three different climbs over the course of a six-or seven-hour ride. A 12-mile climb took about an hour, so that tells you what my days were like.

I rode when no one else would ride, when even my teammates stayed in. I remember one day in particular, May 3, a raw spring day, biting cold. I steered my bike into the Alps, with Johan following in a car. It was 32 degrees and sleeting. I didn’t care. We stood at the roadside and looked at the view and the weather, and Johan suggested that we skip it. I said, “No. Let’s do it.” I rode for seven straight hours, alone. To win the Tour, I had to be willing to do that.

We arrived in Paris for the preliminaries to the Tour, which included a series of medical and drug tests, and mandatory lectures from Tour officials. Each rider was given a Tour “bible,” a guidebook that showed every stage of the 1999 course with profiles of the route and where the feed areas were. We tinkered with our bikes, changing handlebars and making sure our cleats fit the pedals just right. Some riders were more casual than others about the setup of their bikes, but I was particular. The crew called me Mr. Millimeter.

In the pre-race hype, our U.S. Postal team was considered a long shot. Few cycling fans believed we had a chance of winning. Instead they talked about Abraham Olano, the reigning world champion from Spain. They talked about Michael Boogerd of Holland, one of the world’s top three riders, who had beaten me by less than a tire width three months earlier in a one-day race, which really pissed me off. They talked about Alexander Zulle of Switzerland, a strapping blond strongman without an ounce of give-up, as I would learn throughout the Tour. They talked about who wasn’t there, the casualties of the previous year’s doping scandals when an unprecedented nine cyclists were disqualified. I was a footnote, the heartwarming American cancer survivor. Only one person seemed to think I was capable of it. Shortly before the race began, someone asked Miguel Indurain who he thought had a good chance of winning. Maybe he knew how I had trained. “Armstrong” was his answer.

The first part of the Tour was the brief Prologue, a time trial in Le Puy-du-Fou, a town with a parchment-colored chateau and a medieval theme park. Although it was only 4.2 miles long, it was a serious test with absolutely no margin for error. You had to sprint flat out—that means speeds of up to 40 m.p.h.—and find maximum efficiency or you would be behind almost before you started. The riders who wanted to contend in the overall needed to finish among the top three or four.

The course began with a sprint of 2.5 miles, and then came a big hill, a steep sufferfest of nearly half a mile—a climb you couldn’t afford to do at anything less than all out. After a sweeping turn, it was a flat sprint to the finish. The course would favor a bullish rider like me, and it had also been perfect for Indurain, who had once ridden it in a record time of 8:12.

Johan was calm and exacting as he plotted our strategy. He broke the race down into sections, or “splits,” with time goals for each increment. He even knew what my heart rate should be during the first sprint: 190.

Our team setup consisted of two follow cars and a van. In one car were Johan and the crew, with our reserve bikes on top, and in the other were team managers and any sponsors who happened to be along for the ride. The van carried additional bikes and our bags and assorted other equipment. If someone got a flat tire, a mechanic was available, and if we needed water or food, the crew could hand it to us.

Johan directed the race tactically from the car. He issued time checks and status reports and attack orders over a sophisticated two-way radio system. Each Postal rider had an earpiece and a small black radio cord around his collar, and was wired with a heart monitor so that Johan could keep track of how our bodies were performing under stress.

In the pre-race hype, our team was considered a long shot. I was a footnote, the heartwarming cancer survivor.

For the Prologue, riders went off in staggered starts three minutes apart. Reports drifted back from the course. Abraham Olano turned in a near-record time of 8:13. Then Alexander Zulle actually broke the record at 8:09.

It was my turn. When I’m riding well, my body seems almost motionless on the bike with the exception of my legs, which look like automated pistons. From behind in the team car, Johan could see that my shoulders barely swayed, meaning I was wasting no energy: everything was going into the bike, pumping it down the road.

In my ear, Johan gave me partial-time checks and instructions.

“You’re out of the saddle,” Johan said. “Sit down.”

Not realizing it, I was pushing too hard. I sat down and focused on execution, on the science and technique of the ride. I had no idea what my overall time was. I just pedaled.

I crossed the finish line. I glanced at the clock. It read, “8:02.” I thought, That can’t be right. I looked again. “8:02.”

I was the leader of the Tour de France. For the first time in my career I would wear the yellow jersey, the maillot jaune, to distinguish me from the other riders in the race.

There is really no time to celebrate a stage win in the Tour. First you’re hustled to drug testing, and then protocol takes over. I was ushered to a camper to wash up for the ceremony, and presented with the yellow jersey to change into. As much as I had trained for the Tour, this moment was the one thing I had left out. I hadn’t prepared for the sensation of pulling on that shirt, of feeling the fabric slide over my back.

In Nice, Kik watched on TV as I stepped onto the podium. She jumped around our house, shrieking and making the dog bark. When the ceremony was finally over I walked over to our team camper, where I used the phone to call her. “Babe,” I said.

All I heard on the other end of the line was “Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God!” and she burst into tears. Then she said, “Damn, honey, you did it.”

There was a second supremely sweet moment of victory. As I made my way through the finish area, several members of my old Cofidis team were standing around, the men who I felt had left me for dead in a hospital room.

“That was for you,” I said as I moved past them.

We set off across the northern plains of France. I was the first American riding for an American team, on an American bike, ever to lead the Tour de France. (Greg LeMond, the only American who had ever won the race, rode for French teams.) That morning, I looked at the date: it was July 4.

Suddenly, I got nervous. The yellow jersey was a responsibility. Now, instead of being the attacker, I would be the rider under attack. I had never been in the position of defending the jersey before.

It is called the Race of Truth. The early stages separate the strong from the weak. Now the weak would be eliminated altogether.

The opening stages of the Tour were the terrain of sprinters. We hurtled across the plains on flat and monotonous roads, playing our game of speed chess on bikes. Nerves were taut. Handlebars clashed, hips bumped, tires collided. There was a lot of maneuvering and flicking in the peloton. There were close calls and a couple of classic Tour crashes.

All day, every day, my teammates rode in front of me, protecting me from wind, crashes, competitors, and other hazards. We constantly dodged overeager photographers and spectators and their various paraphernalia: baby carriages, coolers, you name it.

In the second stage, we came to a 2.5-mile causeway called the Passage du Gois, a scene of almost surreal strangeness. The Passage is a narrow blacktop road across a tidal marsh, but the brackish water floods at high tide, covering the road and making it impassable. Even when the road is passable, it’s slick and treacherous, and the edges are covered with barnacles and seaweed.

The peloton was still bunched up, full of banging and maneuvering, and it would be a tricky crossing. The first teams across would have the safest passage, so most of the Postal riders gathered around me and we surged near the front. Along the way, some of our teammates got separated and wound up in a second group. Frankie Andreu and George Hincapie, our team sprinters, got me over with no mishaps, but it was frightening; the road was so slippery under our tires that we hesitated to so much as turn the wheel, and we fought a crosswind that made it hard to keep the bike straight.

Behind us, other riders weren’t so lucky. They rode straight into a massive pileup.

Somebody had hit his brakes, and suddenly there were competitors lying all over the blacktop, victims of a huge chain reaction. The rest of the peloton bore down on them, and still more riders fell. We lost one of our domestiques, Jonathan Vaughters, who banged his head and cut his chin wide open, and had to abandon the Tour altogether. Jonathan had averted disaster in another crash the previous day, when he vaulted headfirst over his handlebars but managed to land on his feet. He earned the nickname El Gato, “the Cat,” from the peloton for that, but now he was out. Tyler Hamilton came away from the crash with a sore knee.

As it turned out, the Passage du Gois was one of the more critical stretches of the race. By getting across the Passage early, I picked up valuable time, while some of those bodies scattered behind me in the road were Tour favorites. Michael Boogerd and Alex Zulle both crashed and fell more than six minutes behind—a deficit that would become more and more important as the race wore on.

Over those first 10 days, I was seeking la balance: I wanted to remain in contention, but also to stay as fresh as possible for the more crucial upcoming stage, a time trial in Metz. I gave up the yellow jersey for the time being as other riders took the lead.

Each night we shared the same routine: massages for our sore legs, dinner, and then we would surf the six channels of French TV available in the hotel. Johan had forbidden me to bring my computer, because I had a tendency to stay up too late fooling around on-line.

We sped on, across the plains, while I hung back, saving myself.

We arrived in Metz for another time trial, and in this one, unlike the brief Prologue, riders would now have an opportunity to win or lose big chunks of time. It is called the Race of Truth. The early stages of the Tour separate the strong riders from the weak. Now the weak would be eliminated altogether.

The trial was 34.8 miles long, which means riding full out for more than an hour. Those riders who didn’t make the time cut would be gone, out of the race. Hence the Race of Truth. It wasn’t enough to be fast; I would have to be fast for more than an hour.

As I warmed up on a stationary bike, results filtered in. The riders went out in staggered fashion, two minutes apart, and Alex Zulle was the early leader with a time of a little over an hour and nine minutes. I wasn’t surprised.

The world champion, Abraham Olano, set off on the course just in front of me. But as I waited in the start area, word came through that Olano had crashed on a small curve, losing about 30 seconds. He got back on his bike, but his rhythm was gone.

My turn. I went out hard—maybe too hard. In my ear Johan kept up his usual stream of advice and information. At the first two checkpoints, he reported, I had the fastest splits.

Third checkpoint: I was ahead of Zulle by a minute and 40 seconds.

I saw Olano ahead of me. He had never been caught in a time trial, and now he began glancing over his shoulder. I jackhammered at my pedals.

I was on top of him. The look on Olano’s face was incredulous, and dismayed. I caught him—and passed him. He disappeared behind my back wheel.

Johan talked into my ear. My cadence was up at 100 r.p.m. “That’s high,” Johan warned. I was pedaling too hard. I eased off.

I swept into a broad downhill turn, with hay bales packed by the side of the road. From out of the crowd, a child ran into the road. I swerved wide to avoid him, my heart pounding. Quickly, I regained my composure, never breaking rhythm. Ahead of me, I saw yet another rider. I squinted, trying to make out who it was, and saw a flash of green. It was the jersey of Tom Steels of Belgium, a superb sprinter who’d won two of the flat early stages, and who was a contender for the overall title. But Steels had started six minutes in front of me. Had I ridden that fast?

Johan, normally so controlled and impassive, checked the time. He began screaming into the radio. “You’re blowing up the Tour de France!” he howled. “You’re blowing up the Tour de France!”

I passed Steels.

I could feel the lactic acid seeping through my legs. My face was one big grimace of pain. I had gone out too hard, and now I was paying for it. I entered the last stretch, into a head wind, and I felt as though I could barely move. With each rotation of my wheels, I gave time back to Zulle. The seconds ticked by as I labored toward the finish.

Finally, I crossed the line. I checked the clock: 1:08:36. I was the winner. I had beaten Zulle by 58 seconds. I fell off the bike, so tired I was cross-eyed. As tired as I have ever been. But I led the Tour de France again. As I pulled the yellow jersey over my head, and once more felt the smooth fabric slide over my back, I decided that’s where it needed to stay.

We had been on the bikes for five and a half hours, struggling. Now it would be a question of who cracked and who didn't.

We entered the mountains. From now Won, everything would be uphill, including the finish lines. The first Alpine stage was a ride of 82.5 miles into the chalet-studded town of Sestriere, on the French-Italian border, and I knew what the peloton was thinking: that I would fold. They didn’t respect the yellow jersey on my back.

I held a lead of 2 minutes and 20 seconds, but in the mountains you could fall hopelessly behind in a single day. I had never been a renowned climber, and now we were about to embark on the most grueling and storied stages of the race, through peaks that made riders crack like walnuts. I was sure to come under heavy attack from my adversaries, but what they didn’t know was how specifically and hard I had trained for this part of the race. It was time to show them.

It would be a tactical ride as much as a physical one, and I would have to rely heavily on my fellow climbers Kevin and Tyler. Drafting is hugely important in the mountains: Kevin and Tyler would do much of the punishing work of riding uphill in front of me, so I could conserve my energy for the last big climb into Sestriere, where the other riders were sure to try to grab the jersey from me.

Some riders were more threatening than others, like Zulle and Fernando Escartin, the lean, hawk-faced Spaniard who was another pre-race favorite. These two would trail me most closely throughout the race. If one of them, let’s say Zulle, mounted an “attack” by trying to break away, one of my Postal teammates, say Kevin, immediately chased him down. A rider like Zulle could get away and be two minutes up the road before we knew it, and cut into my overall lead.

Kevin’s job was to get behind Zulle and stay right on his wheel, letting him know the breakaway wasn’t working—a psychological ploy as much as anything else. This is called “sitting on him.” While Kevin sat on Zulle’s wheel, the rest of my Postal teammates would pull me, riding in front of me, allowing me to draft and catch up. Getting through the day without succumbing to any major attacks is called “managing the peloton,” or “controlling” it.

There were three big cols, or peaks, en route to Sestriere. The first was the Col du Telegraphe, then came the monstrous Col du Galibier, the tallest mountain in the Tour, then Col du Genevre. Last, there would be the uphill finish into Sestriere.

The Spanish attacked us right from the start. Escartin launched a breakaway on the Telegraphe in a kind of sucker play, but we kept calm and refused to expend too much energy too early. On the Galibier, Kevin did magnificent work, pulling me steadily to the top, where it was sleeting and hailing. As I drafted behind Kevin, I kept up a stream of encouragement. “You’re doing great, man,” I said. “These guys behind us are dying.”

We descended the Galibier in sweeping curves through the pines. Let me describe that descent to you. You hunch over your handlebars and streak 70 miles an hour on two small tires a half-inch wide, shivering. Now throw in curves, switchbacks, hairpins, and fog. Water streamed down the mountainside under my wheels, and somewhere behind me Kevin nearly crashed. He had tried to put on a rain jacket, and the sleeve got caught in his wheel. He recovered, but he would be sore and feverish for the next few days.

Now came Col du Genevre, our third mountain ascent in the space of six hours, into more freezing rains and mist. We would ride into a rain shower, then out the other side. At the peak it was so cold the rain froze to my shirt. On the descent it hailed. Now I was separated from the rest of the team, and the attacks kept coming, as if the other riders thought I was going to crack at any moment, and it made me angry. The weaker riders fell away, unable to keep up, and I found myself out in front among the top climbers in the world, working alone. I intended to make them suffer until they couldn’t breathe.

On the descent from Col du Genevre, Escartin and Ivan Gotti, an Italian who had won the Giro d’ltalia that June, gambled on the hairpin turns through the mists, and opened up a gap of 25 seconds. I trailed them in a second group of five cyclists.

We went into the final ascent, the long, hard 19-mile climb into Sestriere itself. We had been on the bikes for five and a half hours, and all of us were struggling. From here on in it would be a question of who cracked and who didn’t.

With five miles to go, I was 32 seconds behind the leaders, still locked in the second group of five riders, all of us churning uphill. These others were all established climbers, the best of them Zulle, burly and indefatigable and haunting me. It was time to go.

On a small curve, I swung to the inside of the second group, Stood up, and accelerated. My bike seemed to jump ahead of the pack. I almost rode up the backs of the escort motorcycles.

From the follow car, a surprised Johan said, “Lance, you’ve got a gap.” Then he said, “Ten feet.”

Johan checked my heart rate so he knew how hard I was working and how taxed my body was. I was at 180, not in distress. I felt as though I was just cruising along a flat road, riding comfortably.

He said, “Lance, the gap’s getting bigger.”

I ripped across the space. In .6 miles I made up 21 seconds. I was now just 11 seconds back of the leaders, Escartin and Gotti. It was strange, but I still didn’t feel a thing. It was ... effortless.

The two front-runners were looking over their shoulders. I continued to close rapidly.

I rode up to Escartin’s back wheel. He glanced over his shoulder at me, incredulous. Gotti tried to pick up the pace. I accelerated past him and drew even with Escartin.

I suited again, driving the pace just a little higher. I was probing, seeking information on their fitness and states of mind, how they would respond. I opened a tiny gap, curious. Were they tired? No response.

“One length,” Johan said.

I accelerated.

“Three lengths, four lengths, five lengths.”

Johan paused. Then he said, almost casually, “Why don’t you put a little more on?”

I accelerated again.

“Forty feet,” he said.

When you open a gap and your competitors don’t respond, it tells you something. They’re hurting. And when they’re hurting, that’s when you take them.

We were four miles from the finish. I drove my legs down onto the pedals.

“You’ve got 30 seconds!,” Johan said more excitedly. In my ear, he continued to narrate my progress. Now he reported that Zulle was trying to chase. Zulle, always Zulle.

“Look, I’m just going to go,” I said into my radio. “I’m going to put this thing away.”

The bike swayed under me as I worked the pedals, and my shoulders began heaving with fatigue. I felt a creeping exhaustion, and my body was moving all over the top of the bike. My nostrils flared as I struggled to breathe, fighting for all the air I could get. I bared my teeth in a half-snarl.

It was still a long haul to the finish, and I was concerned Zulle would catch me. But I maintained my rhythm. I glanced over my shoulder, maybe expecting to see Zulle on my wheel. No one was there. I faced forward again. Now I could see the finish line—it was all uphill the rest of the way. I drove toward the peak.

Was I thinking of cancer as I rode those last few hundred yards? No. I’d be lying if I said I was, though I think that, directly or indirectly, what had happened over the past two years was with me. It was stacked up and stored away, but everything I’d been through—the bout with cancer, and the disbelief within the sport that I could come back—either made me faster, or made them slower, I don’t know which.

As I continued to climb, I felt pain, but I felt exultation too, at what I could do with my body. To race and suffer, that’s hard. But it’s not being laid out in a hospital bed with a catheter hanging out of your chest, platinum burning in your veins, throwing up for 24 hours straight, five days a week.

What was I thinking? A funny thing. I remembered a scene in Good Will Hunting, the movie in which Matt Damon plays an alienated young math prodigy, an angry kid from the wrong side of the South Boston tracks, not unlike me. In the film he tries to socialize with some upper-class Harvard students in a bar, and wins a duel of wits with a pompous intellectual to gain a girl’s affections. Afterward, Damon gloats to the guy he bested, “Hey. Do you like apples?”

“Yeah,” the guy says, “I like apples.”

“Well, I got her phone number,” Damon says triumphantly. “How do you like them apples?”

I climbed those hundreds of yards, sucking in the thin mountain air, and I thought of that movie, and grinned.

As I approached the finish line, I spoke into my radio to my friends in the support car, Johan and Thom Weisel, our team’s chief patron.

“Hey, Thom, Johan,” I said. “Do you like apples?”

Their puzzled reply crackled in my ear.

“Yeah, we like apples. Why?”

I yelled into the mouthpiece, “How do you like them fuckin’ apples!”

I hit the finish line with my arms upraised, my eyes toward the sky.

And then I put my hands to my face in disbelief at what I had just done.

I was making enemies in the Alps. My newly acquired climbing prowess aroused suspicion in the French press, still sniffing for blood after the doping scandal of the previous summer. A whispering campaign began: “Armstrong must be on something.” Stories in L’Equipe and Le Monde insinuated, without saying it outright, that my comeback was a little too miraculous.

I knew there would be consequences for Sestriere—it was almost a tradition that any rider who wore the yellow jersey was subject to drug speculation. But I was taken aback by the improbable nature of the charges in the French press: some reporters actually suggested that chemotherapy had been beneficial to my racing. They speculated that I had been given some mysterious drug during the treatments that was performance-enhancing. Any oncologist, regardless of nationality, would laugh at the suggestion. I had absolutely nothing to hide, and the drug tests proved it.

When you're in the yellow jersey, you catch a lot of wind. My fellow riders tested me on the bike every single day.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Postal team was a blue-uniformed express train. “How do you like them fuckin’ apples?” became our battle cry. We entered the transition stages between the Alps and the Pyrenees, riding through an area called the Massif Central. It was odd terrain, not mountainous but hardly flat either, just constantly undulating so that your legs never got a rest. The roads were lined with waving fields of sunflowers as we turned south toward the Pyrenees.

It was brutal riding; all we did was roll up and down the hills, under constant attack. There was never a place on the route to coast and recover, and riders came at us from all directions. Somehow, we kept most of them in check and controlled the peloton, but the days were broiling and full of tension. It was so hot that in places the road tar melted under our wheels.

On the bike, we were always hungry and thirsty. We snacked on tarts, almond cakes, oatmeal-raisin cookies, nutrition bars—any kind of simple carbohydrate. We gulped sugary, thirst-quenching drinks, Cytomax during the day and Metabol at the end of it.

What did I think about on the bike for six and seven hours? I get that question all the time, and the answer’s not very exciting. I thought about cycling.

Finally, we reached the Pyrenees. We rode into Saint-Gaudens in the shade of the mountains, through a countryside that appeared to be painted by van Gogh. The Pyrenees would be the last chance for the climbers to unseat me: one bad day in those mountains and the race could be lost. I wouldn’t be convinced I could win the Tour de France until we came down from the mountains.

The pressure was mounting steadily. I knew what it was like to ride with the pack in 55th place and finish a Tour de France, but the yellow jersey was a new experience and a different kind of pressure. When you’re in the yellow jersey, as I was learning, you catch a lot of wind. My fellow riders tested me on the bike every single day. I was tested off the bike, too, as the scrutiny I underwent in the press intensified.

All I could do was continue to ride, take drug tests, and assert my innocence. We embarked on the first stage in the Pyrenees, from Saint-Gaudens to Piau-Engaly, a route through seven mountains. This was the same terrain I had trained on when it was so cold, but now as we traveled over col after craggy col it was dusty and hot, and riders begged one another for water. The descents were steep and menacing, with drop-offs along one side of the road.

The stage would finish just over the border from Spain, which meant that all the Spanish riders were determined to win it—and none more than Escartin, who had followed me everywhere. In the midst of the frenetic action, our Postal group got split up and I found myself alone, pursuing Escartin. He rode like an animal. All I could hope to do was limit how much time he made up.

As the mountains parted in front of me on the second-to-last climb of the day, I managed to ride Zulle off my wheel and move into second place. But there was no catching Escartin, who had a two-minute gap. On the last climb, I was worn out and I bonked. I hadn’t eaten anything solid since breakfast. I got dropped by the leaders and finished fourth. Escartin won the stage and vaulted into second place overall, trailing me by 6:19. Zulle was 7:26 back.

The next day, we traveled to perhaps the most famous mountain in the Tour, the Col du Tourmalet. The road to the top soared more than 10 miles into the sky. It was our last big climb and test, and once again we knew we would be under relentless attack. By now we were sick of riding in front, always catching the wind, while being chased from behind. But if we could control the mountains for one more day, it would be hard to deny us the top spot on the podium in Paris.

As we labored upward, Escartin and I shadowed each other. I watched him carefully. On the steepest part of the climb, he attacked. I went right with him—and so did Zulle. Going over the top it was the three of us, locked in our private race. At the peak we looked down on a thick carpet of clouds. As we descended, the fog closed in and we couldn’t see 10 feet in front of us. It was frightening, a high-speed chase through the mist, along cliff roads with no guardrails.

All I cared about now was keeping my main rivals either with me or behind me. Ahead of us loomed a second climb, the Col du Soulor. Escartin attacked again, and again I went right with him. We reached another fog-cloaked summit, and now just one more climb remained in the Tour de France: the Col d’Aubisque, 4.7 miles of uphill effort. Then the mountain work would be over, and it was an all-out drop to the finish at speeds of up to 70 miles per hour.

There were now three riders in front, fighting for the stage win, and a pack of nine trailing a minute behind and still in contention for the stage—among them myself, Escartin, and Zulle. I didn’t care about a stage win. With 2.5 miles to go, I decided to ride safely and let the rest of them sprint-duel while I avoided crashes. I had just one aim, to protect the yellow jersey.

I cycled through the stage finish and dismounted, thoroughly exhausted and pleased to have protected my lead. We had done it, we had controlled the mountains, and after three weeks and 2,200 miles I led the race with an overall time of 86:46:20. In second, trailing by 6 minutes and 15 seconds, was Escartin, and in third place, trailing by 7 minutes and 28 seconds, was Alex Zulle.

The road soared into the sky. If we could control the mountains for one more day, it would be hard to deny us the top spot.

I still wore the maillot jaune.

Oddly, as Paris drew closer, I got more and more nervous. I was waking up every night in a cold sweat, and I began to wonder if I was sick. The night sweats were more severe than anything I’d had when I was ill. I tried to tell myself the fight for my life was a lot more important than my fight to win the Tour de France, but by now they seemed to be one and the same to me.

I wasn’t the only nervous member of our team. Our head mechanic was so edgy that he slept with my bike in his hotel room. He didn’t want to leave it in the van, where it could be prey for sabotage. Who knew what freakish things could happen to keep me from winning? At the end of Stage 17, a long, flat ride to Bordeaux, some nutcase shot pepper spray into the peloton, and a handful of riders had to pull over, vomiting.

There was a very real threat that could still prevent me from winning the Tour: a crash. And I faced one last obstacle, an individual time trial over 35.4 miles around the theme-park town of Futuroscope.

I wanted to win the time trial. I wanted to make a final statement on the bike, to show the press and cycling rumormongers that I didn’t care what they said about me. To try to win the time trial, however, was a risky proposition because a rider seeking the fastest time is prone to taking foolish chances and hurting himself—perhaps so badly that he can’t get back on the bike.

We saw it all the time. Just look at what happened to Jonathan Vaughters, who had split his chin and had to drop out of the Tour. I’d nearly crashed myself in Metz, when the child jumped out in front of me as I came around the tight turn. Zulle would have been only a minute behind me if he hadn’t crashed on the Passage du Gois.

My agent, Bill Stapleton, came to see me in the hotel the night before the stage. “Lance, I’m not a coach, but I think you should take it easy here,” he said. “You’ve got a lot to lose. Let’s just get through it. Don’t do anything stupid.”

The smart play was to avoid any mistakes—don’t lose 10 minutes because of a crash.

I didn’t care.

“Bill, who in the fuck do you think you’re talking to?” I said.

“What?”

“I’m going to kick ass tomorrow. I’m giving it everything. I’m going to put my signature on this Tour.”

“O.K.,” Bill said with resignation. “So I guess that’s not up for discussion.”

I’d worn the yellow jersey since Metz, and I didn’t want to give it up. As a team we had ridden to perfection, but now I wanted to win as an individual. Only three riders had swept all of the time trials in the Tour, and they happened to be the three greatest ever: Eddy Merckx in 1969, Bernard Hinault in 1981, and Indurain in 1992. I wanted to be among them. I wanted to prove I was the strongest man in the race.

My mother flew in for Futuroscope, and I arranged for her to ride in one of the follow cars. She wanted to see the time trial but it frightened her as much as anything, because she understood cycling well enough to know how easily I could crash—and she knew this day, the second to last of the race, would either make it or break it for me. She had to be there for that.

A time trial is a simple matter of one man alone against the clock. The course would require roughly an hour and 15 minutes of riding flat out over 35.4 miles, a big loop through west-central France, over roads lined by buildings with red tiled roofs and farm fields of brown and gold grass, where spectators camped out on couches and lounge chairs. I wouldn’t see much of the scenery, though, because I would be in a tight aerodynamic tuck most of the time.

The riders departed in reverse order, which meant I would be last. To prepare, I got on my bike on a stationary roller and went through all the gears I anticipated using on the course.

While I warmed up, Tyler had his go at the distance. His job was to ride as hard and fast as he could, regardless of risk, and send back technical information that might help me. Tyler not only rode it fast but led for much of the day. Finally, Zulle came in at 1 hour 8 minutes 26 seconds to knock Tyler out of first place.

It was my turn. I shot out of the start area and streaked through the winding streets. Ahead of me was Escartin, who had started three minutes earlier.

My head down, I whirred by him through a stretch of trees and tall grass, so focused on my own race that I never even glanced at him.

I had the fastest time at the first two splits. I was going so fast that in the follow car, my mother’s head jerked back from the acceleration around the curves.

After the third time check I was still in first place at 50:55. The question was: could I hold the pace on the final portion of the race?

Going into the last 3.7 miles, I was 20 seconds up over Zulle. But now I started to pay. I paid for the mountains, I paid for the undulations, I paid for the flats. I was losing time, and I could feel it. If I beat Zulle, it would be by only a matter of seconds. Through two last, sweeping curves, I stood up. I accelerated around the comers, careful not to crash but still taking them as tightly as I could—and almost jumped a curb and went up on the sidewalk.

I raced along a highway in the final sprint. I bared my teeth, counting, driving. I crossed the line. I checked the time: 1:08:17.

I won by nine seconds.

I cruised into a gated area, braked, and fell off the bike, bent over double. I had won the stage, and I had won the Tour de France. I was now assured of it. My closest competitor was Zulle, who trailed in the overall standings by 7 minutes and 37 seconds, an impossible margin to make up on the Final stage into Paris. In elite cycling, to make up even two minutes in a day is considered a great effort.

I was near the end of the journey.

But part of me still didn’t entirely trust that I was going to win. I told myself there was one more day to race, and after dinner I stayed sequestered, got my hydration and my rubdown, and went to bed.

The final stage, from Arpajon into Paris, would be a largely ceremonial ride of 89.2 miles. According to tradition, the peloton would cruise at a leisurely pace until we reached the Arc de Triomphe, where the U.S. Postal team would ride at the front onto the Champs-Elysees. Then a sprint would begin—this was still a prestigious stage to win—and we would race 10 laps around a circuit in the center of the city. Finally, there would be a post-race procession, a victory lap. But the Final stage isn’t always irrelevant to the final outcome. In 1989, it was the decisive moment of the entire tour when Greg LeMond came from behind to win a sprint to the finish. It was a great moment for him and a terrible one for Laurent Fignon, who lost by eight seconds after three weeks of racing.

This year, as we rode toward Paris with my victory a foregone conclusion, I did interviews from my bike and chatted with teammates and friends in the peloton. I even ate an ice-cream cone. The Postal team, as usual, rode in superbly organized fashion. “I don’t have to do anything,” I said to one TV crew. “It’s all my boys.”

Finally, we approached the city. I felt a swell of emotion as we rode onto the Champs-Elysees. The entire boulevard was shut down for us, and it was a stunning sight, with hundreds of thousands of spectators lining the avenue of fitted cobblestones and brick. Homs were blowing, the air was full of confetti, bunting hung from every fagade. The number of American flags swirling in the crowd stunned me.

The 10-lap sprint to the finish was oddly subdued. I simply avoided a last freak crash. And then I crossed the finish line. It was finally tangible and real. I was the winner.

I dismounted into pandemonium; there were photographers everywhere, and security personnel, and protocol officials, and friends, clapping me on the back—there must have been 50 people from Austin.

I was ushered to the podium for the victory ceremony, where I raised the trophy after it was presented to me and accepted the first-place check of $400,000. (I would follow Tour tradition and split the money with my teammates.) I couldn’t contain myself anymore, and leapt down and ran into the stands to embrace Kristin. The photographers surrounded me, and I said, “Where’s my mom?,” and the crowd opened and I saw her and grabbed her in a hug. The press swarmed around her, too, and someone asked her if she thought my victory was against the odds.

The smart play was to avoid mistakes. I didn't care. "I'm going to kick ass tomorrow," I said. I’m putting my signature on it."

“Lance’s whole life has been against all odds,” my mother told him.

We were whisked away as a team, to get ready for that night’s celebration banquet, an elaborate fete for 250 people at the Musee d’Orsay, surrounded by some of the most priceless art in the world. To a man we were exhausted, utterly depleted by the three-week ordeal, but we looked forward to raising a glass.

We arrived at the museum to find the tables exquisitely set, except for the rather odd centerpieces.

There was an arrangement of apples at each place.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now