Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE IMPORTANCE OF BEING HAMLET

For a hot young actor looking to show his muscle, Hamlet is the ultimate proving ground. Mel Gibson, Keanu Reeves, and Ralph Fiennes lead the charge as a whole new generation walks the parapets of Elsinore

Theater

DAVID KAMP

You are Keanu Reeves. You have recently established yourself as a credible box-office draw with Speed, and your role as a bisexual hustler four years ago in Gus Van Sant's My Own Private Idaho suggests that you are capable of doing serious, daring work. Yet there persists a notion that your allure and seven-figure-per-picture income can be summed up in three words: "exotic good looks." It hardly seems fair. You want to prove otherwise. You want to make your talents known. You want—but soft, what's this?

"Let not the royal bed of Denmark be / A couch for luxury and damned incest..." whispers the king's ghost through the vapors. "Adieu, adieu, Hamlet. Remember me."

"Now to my word," you respond. "It is 'Adieu, adieu, remember me.' / I have sworn't."

So it was that this past January great herds of Manitobans nightly packed themselves into a regional theater in Winnipeg to see their countryman-made-good, Toronto's own Keanu, essay the ultimate challenge for a male actor: The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. That a young actor would want to take on the role of the grumpy Dane is hardly unprecedented: Ralph Fiennes is presently doing a Broadway-bound Hamlet in London with the Almeida Theatre Company (he'll reach these shores in April); a British up-and-comer named Stephen Dillane is being hailed as a Hamlet for the ages in Sir Peter Hall's recent West End production of the play; and last autumn an unknown named Russell Boulter starred in Richard Dreyfuss's violent, primeval version in Birmingham, England. Since 1602, when William Shakespeare's contemporary Richard Burbage inaugurated the role at the Globe Theatre, every "serious" actor worth his salt—David Garrick, Edmund Kean, Henry Irving, Edwin Booth, John Barrymore, John Gielgud, Laurence Olivier, Richard Burton, David Warner, Albert Finney, Christopher Plummer, Derek Jacobi, Jonathan Pryce, Christopher Walken, Kevin Kline, Daniel DayLewis, Kenneth Branagh, and, er, Mel Gibson, to name but a few—has been compelled to try on the black doublet, the brooding countenance, and the skull-fondling.

But really, Keanu Reeves? At first blush, it seems rather like Eddie Vedder attempting Wagner's Siegfried. Shakespearienced though he is, having debuted as Mercutio in a Toronto production of Romeo and Juliet and played mean Don John in Branagh's film adaptation of Much Ado About Nothing, Reeves tends to get in trouble when a part demands an eloquence and emotional range beyond his usual deadened, lost-boy persona. Why, a forgiving public asks of Reeves, did you have to get yourself into Hamlet? Hollywood demands only that you play a mute, a spastic, or a doomed homosexual to pass yourself off as a cerebral, Oscar-worthy actor.

As it turned out, Reeves's Canadian reviews were generally respectful. "I've seen better and worse. He did not embarrass himself," wrote H. J. Kirchhoff in The Globe and Mail. Roger Lewis of the London Sunday Times was positively effusive: "He is one of the top three Hamlets I have seen. ... He is Hamlet."

One can't fault Reeves for his ambition and guts—there's a special pull to Hamlet that transcends the mere highbrow-credential-building urge that drives Hollywood actors to New York every summer to do Shakespeare in the Park. "It's like five parts in terms of what it gives an actor emotionally," says Kevin Kline. "Making it all fit into one part is the challenge." As a sozzled John Barrymore told Ben Hecht years ago, "In my early years, when I was still callow and confused, and still a-suckle on moonlight, I used to prefer Romeo and Juliet to all the other [Shakespeare] plays. But, as my ears dried, I began to detest the fellow, Romeo. A sickly, mawkish amateur, suffering from Mogo on the Gogo. He should be played only by a boy of fifteen with pimples and a piping voice. The truth about him is he grew up and became Hamlet. There, if ever, was a scurvy, mother-loving drip of a man! A ranting, pious pervert! But clever, mark you! Like all homicidal maniacs! And how I loved to play him. The dear boy and I were made for each other." Less lyrically, Keanu Reeves praised the role as "physically thrilling. It goes to my brain and into my heart."

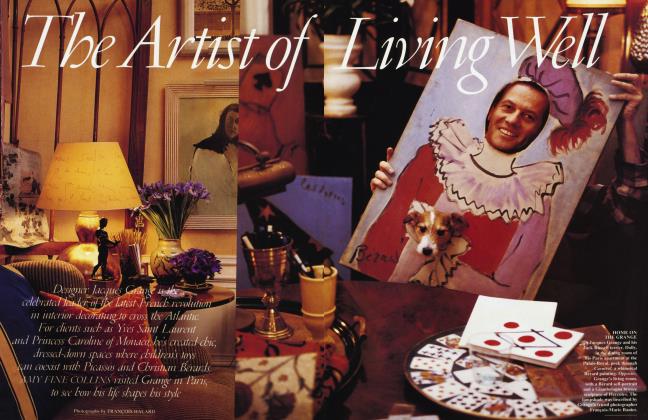

Hamlet is to actors what the New York City Marathon is to runners, what Everest is to mountaineers, what "doing" Jackie O's place was to interior decorators. "For someone like Ralph Fiennes, it's the English Super Bowl, the manly testing ground," says playwright Paul Rudnick, whose antic 1991 comedy, I Hate Hamlet, starred Nicol Williamson, himself once a great Hamlet, and sent up the demented egotism that fueled Barrymore's embrace of the role. "For American actors," says Rudnick, "it's the ultimate James Dean role— Elsinore 90210." Indeed, even the subliterate young Dean imitators who clog the Fox network and the Viper Room are reflexively being Hamlet, Western culture's original angry, misunderstood young rebel.

But if the litany of those who have played Hamlet seems endless, the truth is that many actors spend their careers avoiding the challenge. "It's an awesome task," says Stephen Dillane. "To approach it with anything but trepidation, you must be mad." Physical, emotional, and technical demands aside, you also run the risk of being compared unfavorably to your esteemed predecessors—which is why only the more talented and/or vainglorious actors take on the role, and why we don't hear old theater buffs waxing nostalgic about, say, "Richard Widmark's Hamlet" or "Wally Beery's Dane."

The flip side is that daunting as the play may be—a full, uncut Hamlet can run in excess of four hours—the Dane's role in many ways works in an actor's favor. No matter how he fares in the papers the morning after opening night, he who dares to be Hamlet ensures himself a kind of immortality. Alexander Woollcott, raving over John Gielgud's 1936 Broadway version in one of his "Town Crier" radio broadcasts, put it this way: "I can't pretend that this play is my discovery. Indeed, it was a four-star success before ever the first white men disturbed the peace of the James River in Virginia, and it will still hold humanity enthralled long after. . . . The shouting and the tumult dies. The captains and the kings depart. Still stands the play called HamletHamlet, Prince of Denmark." As the play stands, so do those who have engaged it; theater reviewers collect Hamlets the way wine writers keep logs on Saint-Estephes, and we've become accustomed to reading their rapturous, knowing references to "Gielgud's Hamlet," "Burton's Hamlet," or "Michael Redgrave's Hamlet."

At this particular moment in theater history Hamlet is, inevitably, being interpreted as a sexually ambiguous figure, possibly gay.

Furthermore, no sentient audience member can escape the show's charms. As Olivier wrote late in his life, having played Hamlet at the Old Vic, on the original site of Elsinore, and in his own 1948 movie, "Hamlet is spectatorproof. He fascinates every member of the audience, who recognizes—always—something of himself or herself in the dramatic ebb and flow of Hamlet's moods, his inhibiting self-realizations and doubts, his pitiful failure to control events." And just as Hamlet has come to be seen as the embodiment of us all—what Frank Kermode refers to as "the world's remaking of Everyman in Hamlet's image"—so has the play come to be seen as immensely adaptable and subject to artistic interpretation, to the point where Hamlet is routinely treated as a parable for whatever time and place you happen to be seeing it in. Michael Billington, writing recently in The Guardian, called David Warner's 1965 Hamlet for the Royal Shakespeare Company "very much the Hamlet of the Sixties. . . . His long, lank frame, his rust-red ruffler, his tow-haired uncertainty went straight to the heart of a generation of misunderstood students." Jonathan Pryce, perhaps mindful of the gut-wrenching malaise that was gripping England and America alike in 1980, actually summoned Hamlet pere's ghost from his intestines; the dead king issued his admonitions through Pryce's mouth in gaseous bursts, Linda Blair-style. Branagh played Hamlet in 1992 as a sort of mopey Prince Charles presiding over the dissolution of a troubled royal family. And at this particular moment in theater history, with Dillane playing the prince on the heels of having appeared in the London production of Angels in America, Hamlet is, inevitably, being interpreted as a sexually ambiguous Figure, possibly gay. ("'Tis unmanly grief," admonishes Claudius in Act One. So there you go.)

This tradition gives an actor considerable leeway, not to mention margin of error: even an atrocious or uneven performance can be passed off as a bold "interpretation." The notoriously fragile Daniel Day-Lewis walked off the stage in the midst of a performance in the Royal National Theatre's 1989 production, never to return, having conflated the dead King Hamlet's apparition with that of his own dead father, the poet Cecil Day-Lewis—a succinct expression of Hamlet's angst if ever there was one. Barrymore boasted of playing Hamlet dead drunk on a London stage: "The heat of the footlights made me dizzy. I had to lean on Polonius to keep from falling on my face. I had to make several unrehearsed exits in order to vomit in the wings. I returned once barely in time for my soliloquy. Unable to stand, I sprawled in a chair and recited the God-damn speech sitting down and trying to keep from blacking out." Of course, the reviews in the papers the next day were unanimously raves, according to Barrymore. The similarly lauded Dillane concedes that his early performances as Hamlet were inordinately affected by his just having played Prior Walter, the protagonist afflicted with AIDS in Angels in America. "It took a while to shake Prior off," he says. "There was a fair bit of him in my Hamlet the first few weeks—a lot of hysteria. They are both dying men."

For such actors as Reeves and Mel Gibson, Hamlet may have been a reach, but it reflects well upon them that they tried. For the more stage-suited of actors, your Ralph Fienneses and Daniel Day-Lewises, playing Hamlet is a rite of passage mandatorily undertaken by all those who hope to be inscribed alongside the greats in The Oxford Companion to the Theatre. On a more personal level, the role is a glorious, if excruciating, challenge. "Having played Hamlet twice," says the 47-year-old Kline, "I'd do it again if the first row was 100 yards away and we decided that Hamlet was a 40year-old perpetual grad student at Wittenberg University. I think playing Hamlet is something an actor should do every 5, 10 years, until you look ridiculous doing it."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now