Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

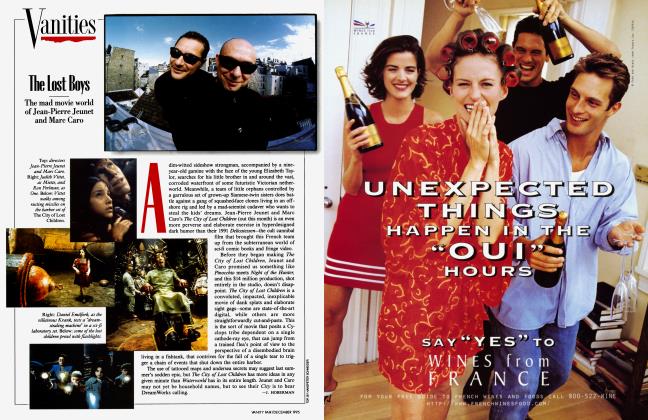

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDeneuve de Jour

A Buñuel-Deneuve triomphe unleashed from filmic bondage

Catherine Deneuve was not yet 23 when Luis Bunuel cast her for the title role in his coolly outrageous Belle de Jour. Many people thought her the most beautiful woman in the world. Look magazine even said so on its cover. Bunuel surely agreed.

First shown here in 1967, Belle de Jour has been out of circulation for at least 15 years.

The current re-release has been engineered by the enterprising Miramax, and the movie fits right into its slate of hits: in its deadpan, deceptively glossy way, Belle de Jour is trickier than Exotica, kinkier than The Crying Game, and more blasphemous than Priest. The erotic reveries of the then 66-year-old Surrealist have scarcely dated. Nor has Deneuve's ineffable chic as the

obscure object of BunueFs desire. As Severine, a well-bred Parisian matron who spends her afternoons working in a brothel, Deneuve appears in varying states of deshabille or, as dressed by Yves Saint Laurent, in many fetching outfits—her body fragmented, almost cubistically, by BunueFs camera into its different, fetishized components.

Perversely unresponsive to the exaggeratedly kind, handsome, devoted, and wealthy young surgeon to whom she is married (and whom she loves), Severine dreams of her husband's latent cruelty and amuses herself by imagining violent or humiliating bouts of anonymous sex. This haute bourgeoise housewife is no ordinary masochist—she is not attracted to pain but, rather, wishes to surrender her will. Severine is fascinated by brothels because, as a friend points out, "in those places one has no choice," although it's entirely her choice to be there (and on her own terms). The madam and whores in the respectable, if less than deluxe, maison where Severine works are never less than impressed with her breeding.

Bunuel, who never presumes to judge his heroine, was commissioned to adapt Belle de Jour from a once shocking psychological novel by Joseph Kessel—the 1928 equivalent of The Story of O. "I hope I can save such a stale subject by mixing indiscriminately and without warning in the montage the things that actually happen to the heroine, and the fantasies and morbid impulses which she imagines," the filmmaker said at the time—and indeed he does. Belle de Jour's, wide-eyed fantasies within fantasies within fantasies (within the framing fantasy of an advertising-perfect Paris) suggest a kind of erotic Alice in Wonderland.

As a movie, Belle de Jour is founded on BunueFs genius for free-associative chitchat and orchestrated Freudian slips. As moment-to-moment unpredictable as Un Chien Andalou or L Age d'Or, the venerable avant-garde shockers the young Bunuel made in collaboration with Salvador Dali, Belle de Jour reaches its climax when Severine's fantasies finally go violently out of control. The movie is, however, teasingly open-ended. In a final joke, suggesting the narrative equivalent of a spacially ambiguous Necker cube, Bunuel offers two mutually exclusive denouements.

Although slammed by irate French reviewers when it first appeared ("One can't believe that such bad dreams could go on inside Catherine Deneuve's pretty head," Le Monde sniffed), Belle de Jour turned out to be BunueFs biggest commercial success. It is also a perfect film.

J. HOBERMAN

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now