Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEDGAR BETS THE HOUSE

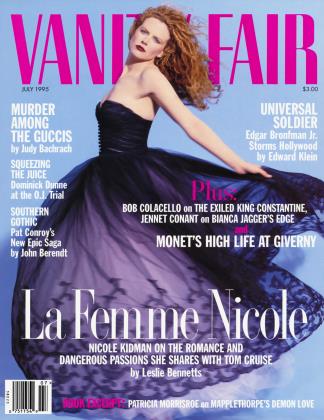

At 16, Edgar Bronfman Jr. fled the tormented history of the House of Seagram and escaped into the movie business. Twenty-four years later, reconciled with his father and wielding the financial might of the family liquor empire, Seagram's young C.E.O. is returning to Hollywood as the proud new owner of MCA and its fabled Universal studio. EDWARD KLEIN chronicles Bronfman's stealthy campaign for that glittering but dangerous prize

EDWARD KLEIN

'Money doesn't make you smart, but it doesn't necessarily make you stupid, either," Edgar Bronfman Jr. said about the merciless thrashing he was taking in the press over his purchase of MCA and its fabled Universal movie studio. "Perilous," "reckless," and "crazy" were just some of the words being used to describe his decision to take a ride down Hollywood's river wild. "There's no doubt about it," continued Bronfman, the president and C.E.O. of the Seagram Company Ltd., the spirits-andbeverage giant founded by his grandfather more than 70 years ago in Canada and bequeathed to him by his father, Edgar Bronfman Sr., "people are more skeptical of a person's ability if he's born with money."

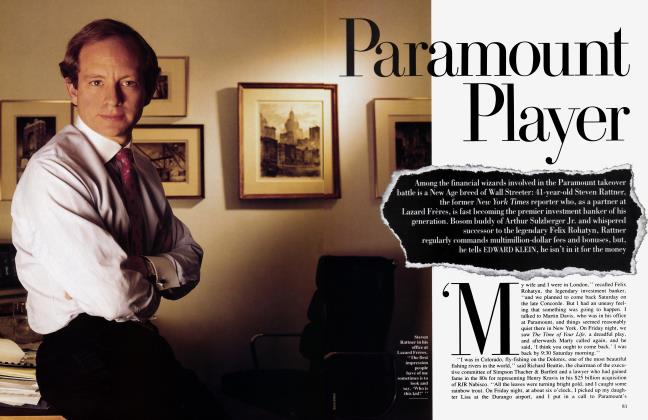

We were sitting in his office on the fifth floor of the Seagram Building, overlooking Park Avenue. Draped in Armani, Bronfman looked elegantly casual, but his stiff body language conveyed a different message. Like most inheritors of great wealth, he didn't have much pracr tice in justifying himself to strangers, and he was understandably uncomfortable talking to a reporter.

He was telling me about an extraordinary secret trip he had taken to Japan this past March, which led to the acquisition of MCA. "Going by myself to Japan was the key to the deal," Bronfman said. "If you sit around in a roomful of advisers, you feel far less comfortable than you do if you sit one-onone with your counterpart. That's why I went alone. I was convinced that if I could make a reasonable deal, Seagram could be transformed into a company in control of its own destiny."

By the time the Seagram Gulfstream IV jet touched down at Japan's Kansai International Airport on the afternoon of March 6, he said, he had been traveling for 16 straight hours. He was whisked off to the Miyako Hotel, where he barely had time to change from his jeans into a suit before rushing to a dinner appointment at a guesthouse in Kyoto. There he slipped off his shoes and ducked as he entered the Japanese-style tatami room.

Six feet three inches tall and weighing about 170 pounds, Bronfman is a handsome man, whose long attenuated nose, brooding expression, and reddish beard lend him a striking resemblance to the van Gogh portrayed by Kirk Douglas in Lust for Life. He celebrated his 40th birthday in May, but he looks and acts a good deal older, in part no doubt because of the crushing burden of running the House of Seagram, but perhaps in part, too, because he is driven by a consuming desire to establish his legitimacy and gain control over his own destiny, as well as that of his family's $6-billiona-year business.

It was Bronfman's fate to inherit Seagram, one of the world's largest producers and marketers of distilled spirits, just as public tastes in liquor were undergoing a dramatic shift and global liquor sales were shrinking. In response, he has spent a great deal of Seagram's money replacing its traditional low-end "brown" drinks with such high-margin brands as Martell cognac, for which he shelled out $850 million. He won vast distribution rights for the Gen-X drink of choice, Absolut vodka. He diversified the Seagram mix outside of its core liquor business by spending $1.2 billion to purchase Tropicana and another $2.2 billion to buy a nearly 15 percent interest in Time Warner.

By the time he arrived in Japan, he had plans to build a multibilliondollar war chest for a major foray into the media-entertainment-communications industry, which he is convinced is where the action will be in the next century. To speed along that process, he had decided to divest Seagram of nearly all of its 163 million shares of E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, a stake which had more than tripled in value to $9 billion since Seagram acquired it in 1981, and which accounted for nearly half of Seagram's annual profits.

"I asked myself, what kind of company did I want to leave when I passed on the baton, as my father had passed on the baton to me?" he said. "And the answer was, I wanted to leave a company that would outgrow the Standard & Poor's 500. The opportunity to do that with so large a percentage of Seagram's capital tied up in DuPont—half to 75 percent— wasn't there. That wasn't the way to create superior growth."

When MCA unexpectedly became available, Bronfman recognized it as the engine for growth he had been looking for. In order to win it, however, he knew that he would have to act swiftly, and with stealth, for since he is the scion of the billionaire Bronfmans, as well as a descendant on his mother's side of three of the most prominent "Our Crowd" Jewish-American families—the Loebs, the Lehmans, and the Lewisohns—his every move is scrutinized closely by the business community.

Considering how thirdgeneration rich kids often turn out, Bronfman strikes people as a refreshing exception to the rule. Ever since Prohibition, the liquor business has been notorious for its strutting, macho types, but Bronfman is dramatically different—a courtly, softspoken gentleman who does not shrink from displaying a sensitive side that makes him appear almost fey. "There's something enigmatic about him," says his friend publisher Jann Wenner. "He likes to talk really quietly so that you listen very carefully. But he's tough and he's proud of that. It's a part of him that he likes and that he nourishes."

"Edgar has no artifice," says Barry Diller, a friend who has known Bronfman since Edgar junior's late teens. "He is comfortable with himself, comfortable with his environment and with other people in a complete sense that is rare. I know maybe half a dozen people I see that in. He has extremely solid values. He intends to leave what he touches better than he got it."

Nonetheless, the jury is still out on Bronfman when it comes to the bottom line. His purchase of Tropicana was generally judged to be something of a disappointment, and his investment in Time Warner has produced little more than a frustrating feud with Gerald Levin, its embattled chairman, who erected a poison-pill defense against a Seagram takeover. In short, Bronfman has yet to prove that he deserves his impressive titles—he added C.E.O. to president at the age of 39—or his handsome remuneration, which amounted in 1994 to $846,000 in pay, $840,000 in bonuses, and millions in stock options.

Like his much-married father, who dallied in Hollywood in his heyday, Edgar junior struggled to overcome the reputation of being a starstruck dilettante. As a privileged youngster growing up on Park Avenue, he was an unremarkable student at Collegiate, the prestigious prep school, and skipped college in order to write popular songs and produce movies. He ran with a glittering show-business crowd, and numbered among his friends Wenner, Diller, Lome Michaels, Michael Douglas, banker Herbert A. Allen, billionaire Ronald Perelman, and agent-cum-dealmaker Michael Ovitz, who was a prime candidate to run MCA if Bronfman acquired it.

When people gossiped about Bronfman, they talked about his once stormy relationship with his father, and his rebellious young manhood, which included a marriage to a beautiful black actress named Sherry Brewer.

"At heart," says Paul Ford, a lawyer at Simpson Thacher & Bartlett and one of Bronfman's closest friends, "he's a very private guy. He's very responsible, a person of real substance. He cares deeply about his family. When his older brother's first wife was dying of cancer, Edgar junior dropped everything and went out to the West Coast to spend time with them. I find it ironic that he's being portrayed in the press as this superficial guy. Nothing could be further from the truth."

To prepare for his Japanese trip, Bronfman asked his advisers to put together briefing material on the man he was scheduled to meet: Yoichi Morishita, the recently appointed president of the Matsushita Electric Industrial Company, one of the world's largest consumer-electronics manufacturers. "On the way over to Japan," Bronfman said, "I read some of Morishita's speeches to his executives. They were long and detailed, also straightforward, determined, and sometimes even quite harsh. His remarks struck me as quite different than my experience with Japanese managers would have led me to expect. I felt that if he wanted to do a deal there would not be a lot of ceremony."

"Sid said, 'I don't want that job. I want to do something else."

Morishita turned out to be a tough, solidly built salesman who did not speak a word of English. His giant, $65-billion-a-year company, Matsushita, dominates the city of Osaka. Morishita had little in common with his smooth-talking, Tokyo-based rivals at Sony—Akio Morita *and Norio Ohga—which owns Columbia and TriStar Pictures, and he was not part of the original Matsushita team that bought MCA back in 1990 for $6.6 billion, the most expensive investment in the United States ever made by a Japanese company.

In the months since taking over, Morishita had been engaged in an embarrassing public dispute with Lew Wasserman and Sidney Sheinberg, MCA's proud pair of American managers. Wasserman had come away from the sale of MCA with a staggering $327 million, and though that left him technically a Japanese employee, he was still, at 82, considered Hollywood's eminence grise. A subtle, secretive man, Wasserman had run MCA for almost half a century, the past 35 years with his inseparable sidekick, Sheinberg, a caustic former lawyer, who made about $120 million on the sale to Matsushita.

From the start, the MCA-Matsushita marriage was a grand misalliance, in which the Japanese treated MCA like a minor corporate division, and Wasserman and Sheinberg behaved as though they had never sold the company. In recent years, Sheinberg had rarely missed an opportunity to humiliate his Japanese bosses in public, threatening that he and Wasserman would not renew their contracts, when they expired at the end of 1995, unless they were ceded complete control of MCA.

"The Matsushita people venerated Lew Wasserman for what he had accomplished over the years at MCA, and for being the patriarch of Hollywood," said Herb Allen, the immensely influential entertainment-industry investment banker, who was retained by Matsushita in its sale of MCA. "But they weren't getting along with Lew's number two at MCA, Sid Sheinberg. Sid was hitting them broadside, and they were confused. We told them that Sid was a straight and honorable guy. But they kept on asking, 'Why is Mr. Sheinberg saying these awful things about us?'"

"At, CAA, Mike is king. At MCA, he would only be the prince."

"What Edgar did was highly unusual, even in American corporate culture," said Stephen Volk, the senior partner of Shearman & Sterling and the lawyer who represented Seagram in the MCA deal. "Here was a C.E.O. going off by himself to Japan, with no staff and no aides, to establish a relationship of trust and confidence. He presented a contrast between himself and Sid Sheinberg."

'I found lots of similarities between the management philosophy of Konosuke Matsushita, the founder of the Japanese company, and my grandfather Samuel Bronfman," Bronfman said. H "Both of our companies have a commitment to improving society and behaving responsibly. My grandfather published his first moderation-in-drinking ad in 1934, and we've been refining that message for the past 60 years.

"I also wanted to let Morishita know that, for me, MCA was a great series of assets that really could grow into a highly competitive and lucrative communications company. It has the second-largest film-and-TV library in the world, after Ted Turner's. It has a strong music business. A good cash flow. It is the only company that can compete with Disney in the theme-park business. It has a small but strong publishing business. And it has a film studio that hasn't performed as well as it should, but still represents a major asset."

He knew that MCA would fetch a lot of money—Morishita had originally thought of asking $10 billion—but Bronfman did not bring up the subject in this first meeting. Instead, he spoke of his personal commitment to the entertainment business. His passion for movies and music was so obvious that it practically transcended the language barrier, and as an aide translated his words into the formal idioms of Japanese, Yoichi Morishita nodded.

The two men resumed their discussion at 8:30 the next morning. Bronfman was aware that Morishita had a number of other suitors for MCA. A year and a half before, a Matsushita executive had traveled to Denver to discuss selling a nearly 25 percent interest in MCA to John Malone, the head of Tele-Communications, Inc., the largest cable company in America. More recently, the Dutch owners of Philips, the Australians from News Corporation, and the Germans from Bertelsmann had all made overtures to Matsushita, and Ronald Perelman was said to be preparing his own bid.

"We didn't want to get into an auction," Bronfman said. "We felt that if we could acquire this company sensibly and fairly, O.K. But Seagram had no interest in pursuing an auction and bidding up the price. I told Morishita, 'If we want to do this quickly, it would be helpful for us to see your valuations of the various divisions of the company.' I also said, 'We would like an exclusive period of time to formulate a proposal.'"

Morishita agreed to both requests— with one important proviso. He did not want Sheinberg and Wasserman to get wind of the negotiations. Bronfman accepted the condition of confidentiality and promised that he would be back within 18 days. The two men stood and shook hands.

In less than 24 hours, they had put into motion one of the most important deals in Hollywood history.

'If I do well, I have 25 years in this job," Bronfman told me. "If I do poorly, I have significantly less time." A littie more than a week had passed since he had signed an agreement in principle to pay $5.7 billion for 80 percent of MCA. That left Matsushita with a face-saving 20 percent and, taking into account the sharp rise in the value of the yen, a foreign-exchange loss of about $2 billion. In Hollywood, the deal was compared to Japan's surrender aboard the battleship Missouri at the end of World War II.

Bronfman's name was splashed all over the papers, and his face was on TV. It was said that he had embarked on a risky course of action that was certain to change the legacy of his family business. What's more, he had set in motion powerful forces that would bring an end to the Wasserman-Sheinberg reign at MCA and could also affect the relative ranking of the major studios and talent agencies, as well as alter the futures of Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg, and David Geffen and their new DreamWorks SKG studio. Though Barry Diller and Warner Bros, co-chairman Terry Semel were among those mentioned as the possible new head of MCA, speculation centered on Michael Ovitz, who had been a key Bronfman adviser on the MCA purchase. Everyone said that it would take an extraordinary offer—hundreds of millions of dollars in rights, options, warrants, and bonuses—to lure him away from CAA, the Hollywood agency he had created, and even all that might still not be enough. Many were just as certain that, whoever ended up with the top title at MCA, Bronfman would keep "the Lew Wasserman seat" for himself.

"Morishita is I not entitled to insult a man who has done what Lew Wasserman has done.

In Bronfman's office, a Miro and a Picasso share wall space with a photograph of Mr. Sam, as Bronfman's grandfather was known until his death in 1971. Beneath the portrait of the pugnacious Seagram founder is a copy of his most famous saying: "Shirtsleeves to shirt-sleeves in three generations. I'm worried about the third generation. Empires have come and gone."

That concern is now shared by many in the financial community, who point out that Seagram bought a studio that was in danger of losing its shirt on Waterworld, the Kevin Costner movie alleged to have cost as much as $175 million and scheduled for release in July. In the course of the MCA purchase, Seagram's stock plunged by almost 20 percent, giving the Bronfmans, who own 36 percent of the company, a reported paper loss of about $800 million. The Wall Street Journal, which was the hardest on Edgar junior, attributed his motives to "a lifelong infatuation" with Hollywood, and suggested that the first movie made under the Seagram banner at MCA should be called Dumb and Dumber II.

"It's a nutty thing he's doing," an investment banker told me. "A studio is like a ball team: you make money when you sell, but there's not much cash flow in between. Given the large amount of growth in that business, you can make the case that on an asset basis, not an earnings basis, with good management, you could have real value over time. But it's a play. It's a guess."

"I'm dumbstruck," said a chief executive who, like Bronfman, had inherited a giant family business. "I'm not saying they shouldn't have gotten out of DuPont and put their own and their stockholders' money to better use. But this is gunslinging. Father and son played around in Hollywood, fine, but that's very different than betting the crown jewels."

Not everyone saw it that way, however. "MCA is a great company that has been run by conservative businessmen," said David Geffen, who, along with his DreamWorks partners, wasted no time opening negotiations with Bronfman over a possible future business relationship. "It's an underexploited asset, the equivalent of where Disney was when it was taken over 11 years ago by Michael Eisner. Frankly, Edgar's gotten a good deal."

"We bought MCA with no debt," Bronfman said. "Matsushita has eaten the costs of Waterworld. . . . Let's say that between postproduction and marketing the movie will cost us $57 million. That's 1 percent of what we paid for MCA. If it is the biggest hit in creation, it won't make any difference. And if it's the biggest flop in creation, it won't make any difference, either, from a financial standpoint. But if you're going to print that, print this: We're going to make every effort to make Waterworld a hit. You stand behind your creators in good times and bad. Kevin Costner is a great star and filmmaker, and I want to stick with him, and I've told him that."

The intense public scrutiny was beginning to take its toll on Bronfman, who had dropped almost 10 pounds in the month following the deal. To avoid the press on his trips to Los Angeles, he started checking into the Hotel Bel-Air under the pseudonym "Mr. Alcock"—his second wife's maiden name.

He got a lot of support from his father, a virile-looking man of 66. "Psychotherapy alone was not responsible for Edgar's and my relationship improving," he said, referring to his father by his first name, "but it would also be inaccurate to say it's had nothing to do with it. A relationship takes two people, and both Edgar and I have grown."

Four years ago, when Edgar senior married for the fifth time, to Jan Aronson, an artist, Edgar junior donated money in their name for an art program run by the Fund for New York City Public Education. Edgar senior devotes most of his time to the major passion of his latter years, the World Jewish Congress, of which he is president and chief financial benefactor. He can well afford it; the latest Forbes-magazine ranking of America's richest people estimates that Edgar Bronfman Sr. has a personal net worth of $2.5 billion. Edgar junior makes no secret of the fact that he has never been as close to his father as he is to his mother, the former Ann Loeb, the daughter of John Langeloth Loeb, the ex-chairman of Loeb, Rhoades & Company, and the former Frances Lehman.

Edgar junior and his second wife, Clarissa, a tall Venezuelan beauty, whom he married less than a year and a half ago, live in a town house on Manhattan's Upper East Side, which was occupied in the 1970s by Edgar junior's mother after she left his father. There is a gym, where both Edgar and Clarissa, who excelled at broadjumping in her native country, work out. The house is filled with antiques and comfortable chintz-covered chairs and sofas. Recently, Bronfman plunked down $4.4 million for a five-story town house on a nearby side street, which he is gutting and redoing for them.

Bronfman and Morishita had put into motion one of the most important deals in Hollywood history.

Edgar's two-and-a-half-year-long courtship of Clarissa was typical of his relentless determination. During one period of his romantic pursuit, he sent her two dozen roses, then two dozen orchids, every day. Clarissa finally relented. She is from a wealthy family: her father, a former high-ranking executive in Petroleos de Venezuela, the state-owned oil monopoly, is retired; her mother comes from an old Venezuelan family that controlled extensive land interests. Not surprisingly, Clarissa's Catholic parents did not see Bronfman as an ideal catch, and Clarissa is fond of telling the story of how she broke the news that they were going to get married. "She said, 'There are a few things I have to tell you about him,' " according to Bronfman. " 'One, he's Jewish. Two, he's been married before. And three, he's got three children.'"

The wedding was presided over by a rabbi, a priest, and a local bishop, and it took place on the mountaintop property in Caracas owned by Clarissa's grandmother. The ceremony was a grand, torchlit production attended by 1,200 people. At the reception, there were three bands, and Bronfman's longtime music collaborator, Bruce Roberts, sang a song that he and Bronfman had written for Barbra Streisand, which she has yet to record, called "If I Didn't Love You."

On alternate weekends, Bronfman and Clarissa climb into their van and pick up his three children—ranging in age from 7 to 14—who live with their mother in a town house on Riverside Drive. They then head to Bronfman's 125-acre Pawling estate in New York's Dutchess County, which has an 11-acre lake, a tennis court, an indoor swimming pool, and a private golf course. The red-brick, 12,000square-foot Georgian mansion once belonged to radio newsman Lowell Thomas, and it had passed through the hands of Dino De Laurentiis before Bronfman bought it for $3 million.

When he finds time, Bronfman still writes songs with Bruce Roberts. "A few weeks ago," Roberts told me, "during the most crucial part of the negotiating for MCA, I kept calling him and annoying him for a lyric. He told me, 'Honey, I love you, but I'm too busy at the moment.' I have a new CD coming out on Atlantic in August," Roberts continued. "Edgar wrote one of the songs, called 'Intimacy,' for Clarissa." Roberts then sang the first stanza:

Intimacy, I bless you.

I worship at your feet.

You're the gentle breath on an open sore,

You're the savior I've been waiting for.

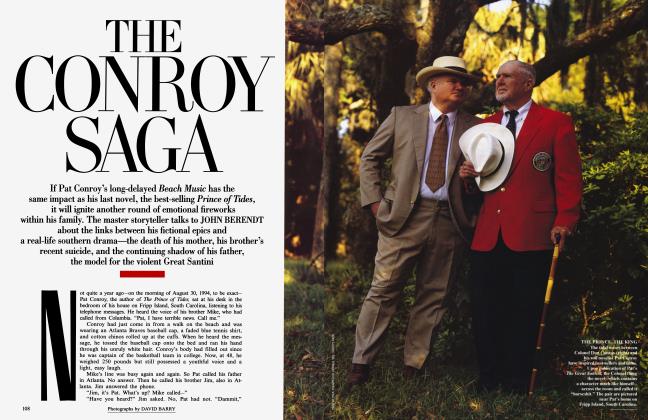

To understand Edgar Bronfman Jr.'s open sore, it is necessary to know something about the tangled Bronfman family history. "I didn't know him very well," Bronfman told me about his paternal grandfather. "He passed away when I was 16. But he was such a canny businessman that I think he'd see the potential and the opportunity in MCA."

Samuel Bronfman (the family name means "whiskey-man" in Yiddish) was not a man to miss an opportunity. The Bronfman family was washed ashore in Canada as part of the late19th-century wave of Jewish immigration from the East European Pale of Settlement. Sam and his three brothers, Abe, Harry, and Allan, started off in the hotel business in the frontier towns of Manitoba. "Many years later, in 1951," Mordecai Richler wrote in the Canadian magazine Saturday Night, "a small-time hoodlum, testifying before Estes Kefauver's Special Senate Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in the U.S., volunteered that the Bronfmans' prairie railroad hotels were actually a chain of whorehouses. Confronted

with this story in his last years, Sam countered, 'If they were, they were the best in the West.'"

Sam was a brilliant, profane, harddrinking man, and, like Joseph P. Kennedy, he made his fortune in bootlegging. "The Bronfman customers during Prohibition," wrote Peter C. Newman in his biography of Sam, King of the Castle, the Making of a Dynasty: Seagram's and the Bronfman Empire, "were an army (and navy) of bootleggers taking delivery in ships off the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, in small craft at handy crossings along the St. Lawrence-Great Lakes system, in cars and trucks at dusty prairie towns bordering on North Dakota and Montana."

Years later, after he had forced his only surviving brother, Allan, out of the liquor business, had merged his operations with the venerable Joseph E. Seagram and Sons Inc., and had built a huge mansion in the posh Westmount section of Montreal, Sam tried to sanitize his early history. He hired his own personal poet laureate, A. M. Klein, who composed panegyrics to Sam on his birthdays and important business occasions. Sam desperately wanted to be accepted by the ruling elite, and, above all, to be made a senatorin Canada, a prestigious lifetime appointment. He never achieved either of these goals. In the prudish, bigoted atmosphere of Canadian society in the 1920s and 1930s, he was ostracized for being a bootlegger and a Jew, and was refused entry into such "proper" institutions as the Mount Royal Club and the Mount Stephen Club. He reacted to his disappointments by creating an upper-class British fantasy life.

He and his wife, Saidye, who, at age 99, still lives in the Westmount mansion, had four children—Edgar, Charles, Phyllis, and Minda. Sam tried to instill his win-at-any-cost values in his children. The mild-mannered Charles was the least like his father, and yet he chose to remain in Canada, where he was the convenient victim of his father's merciless bullying. Charles became active in Jewish affairs and was a founding owner of the Expos baseball team. He achieved one distinction that had always eluded Mr. Sam; Charles was admitted as a member of the Mount Royal Club.

(Continued on page 129)

(Continued from page 81)

The handsome, haughty Minda moved to France, where she became the Baroness de Gunzburg, and was interested in cultural affairs until her death in 1985 from leukemia. Phyllis became an architect, and in 1954 it was she who personally chose Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson to design the bronze tower that became New York's landmark Seagram Building. A divorcee, Phyllis lives today in a grand loft in a former peanut factory in Montreal, not very far from where she has established what many consider the finest museum of architecture in the world.

When Edgar Bronfman married Ann Loeb in 1953, it was viewed as a brilliant match for both families. The union gave the Bronfmans their long-sought social legitimacy. As for the Loebs, Ann's father was overheard to say at the wedding, "Now I know what it feels like to be a poor relation." To their sumptuous New York apartment Edgar and Ann attracted a glittering circle of friends from the worlds of theater and politics, and they produced a large family consisting of four boys and a girl: Samuel Bronfman II, Edgar junior, Matthew, Adam, and Holly.

Though Edgar junior was the second son, and therefore not first in the direct line of succession, he was a natural leader, and a far more commanding presence than his elder brother, Sam. This gave rise to a tense triangle among the father and his two oldest sons. Matters weren't helped much by the fact that the marriage between Edgar senior and Ann was deeply troubled. Edgar hardly bothered to hide his liaisons with models and society women. And friends of Ann, who was known to be a warm, nurturing woman, said that as the years went by she became increasingly fragile.

"The breakup of the Bronfman marriage was very traumatic for all the kids," said a close family friend. "I don't think Edgar junior assumed real responsibility for anything until that happened. And then he stepped into the breach and became a surrogate father to his siblings."

More family trauma soon followed. In 1973, Edgar senior married a British aristocrat named Lady Carolyn Townshend. On their wedding night, and during their honeymoon in Acapulco, Carolyn refused to sleep with Edgar. "Nels R. Johnson, a friend of the bride's, testified that Dr. Sheldon Glabman, a New York specialist in internal medicine, had boasted that Lady Carolyn had spent most of her wedding night with him," wrote Peter Newman. "Johnson also told the court she had confided to him in Switzerland two months previously that Edgar had screwed a lot of people and 'it gives me a lot of satisfaction to screw him without having to deliver.' "

By the time his father's second marriage ended, Edgar junior was living on his own in Hollywood. He had already worked in London on two movies with the producer David Puttnam, and he was trying to make it as a producer himself.

Bronfman was by his family's side in 1975 after his elder brother, Sam, was reportedly kidnapped and held for $2.3 million in ransom for nine days. In the confusing denouement of this lurid episode, Sam was rescued, and one of the men charged in his kidnapping claimed that the whole thing had been a hoax, and that he and Sam had been homosexual lovers. "I knew Sam Bronfman while we were both teenagers, and I was with him the night before he was kidnapped," said a friend. "I don't believe that Sam is gay. But something happened. And I believe that within the family there was a secret pact that nobody would ever talk about it."

Edgar senior was to marry three more times—twice to the same woman, Georgiana Webb, the daughter of the proprietor of an English pub called Ye Olde Nosebag. The estrangement between him and Edgar junior grew to the point where some people wondered if it was irreconcilable. In the mid-70s, Dionne Warwick, who would later record one of Edgar junior's songs, "Whisper in the Dark," introduced him to her friend Sherry Brewer. Despite—or perhaps because of—his father's vehement objections to an interracial marriage, Edgar junior eloped with Sherry.

Years went by with father and son hardly exchanging a word. "Nobody will believe this," Edgar junior told me, "but when I arrived in Hollywood my trust fund was $20,000 a year. I was working for a living. I lived on my per diem from Universal. I didn't have any money."

However, in 1982 Edgar junior was persuaded to invite his father to a dinner at La Cote Basque in New York celebrating the premiere of The Border, his first major Hollywood project, starring Jack Nicholson. The next day the two of them sat down in the Seagram offices for their first heart-to-heart talk in a long time. Edgar senior, who was 51 at the time, was growing weary of his corporate responsibilities. Edgar junior, who was nearing his 30th birthday, was growing unhappy in his marriage and career.

"Will you join the company with a view to eventually running it?" his father asked.

"If my brother Sam had said, 'No, don't take it,' I wouldn't have accepted my father's offer," Bronfman told me. "Because to do it against his wishes would have created a situation which we're in business to avoid: a schism in the family. The whole point is that the family acts together, works together, and invests together, in a vehicle called Seagram."

'Edgar junior needed to establish his identity and legitimacy in his own eyes first," said the writer Barbara Goldsmith, who has known the Bronfmans since childhood.

After serving apprenticeships in London and New York, young Bronfman was made president of Seagram in 1989. About four years ago, he turned his attention to long-range planning. As his right-hand man, he chose Stephen Banner, a brilliant, 53-year-old strategist who had been head of corporate law at Simpson Thacher. Seagram's 24 percent stake in DuPont was in many respects a sweet deal; it produced $300 million a year in dividends at a very low, 7 percent intercorporate tax rate. But it was like a one-stock mutual fund—a passive investment that promised little future growth. Bronfman wanted to avoid selling the DuPont shares on the open market and incurring a capital-gains tax of about $2.1 billion. Instead, he arranged to sell the shares directly back to DuPont—a sale in which the proceeds would be counted as corporate dividends, carrying a tax liability of only $615 million.

"What you had in Edgar junior," said Herbert Allen, "was a young, active, aggressive manager, who wanted to transform his company from a mutual fund to being an operating company, and once he made that decision, it was only a question of 'What would I be good in, and what do I like?"'

"As I went around the world," Bronfman told me, "there was one invariably accepted United States export that dominated its field—popular culture, whether sports, entertainment, or fashion. It's an extraordinary force in international markets, and I believe we have just begun to tap those markets, especially in China and India, with their two billion people."

Seagram already had a foothold in the pop-culture future, thanks to its stake in Time Warner, the largest communications company in the world. Over a period of months, Bronfman and Time Warner chairman Jerry Levin lunched regularly on the balcony in the Grill Room of the Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram Building, and at one point Bronfman offered Levin up to $3 billion to help pay down his company's mountainous $15 billion debt. In return, Bronfman wanted at least a couple of seats on the Time Warner board. Levin, fearing a creeping takeover, didn't even accord Bronfman the courtesy of an answer. Frustrated and annoyed, Bronfman began about a year and a half ago to look elsewhere.

While Bronfman was shopping for an entertainment company, Yoichi Morishita, the president of Matsushita, was running into serious trouble in Hollywood with MCA. "The Matsushita people are essentially very solid businesspeople, but they bought something they didn't understand," said an American who had worked with Matsushita during its 1990 purchase of MCA. "With a little help from American management, courtesy, and respect, a lot of problems could have been avoided. But Sid Sheinberg and Lew Wasserman studiously kept anyone who had been close to Matsushita away from MCA. They poisoned the well with all of the advisers who had served Matsushita with the purchase of MCA, including the lawyers at Simpson Thacher, Mike Ovitz, and Herb Allen."

Morishita, a no-frills executive, did not have a personal stake in his company's glamorous Hollywood venture. He had come to power following a disastrous, multimillion-dollar recall of faulty Matsushita refrigerators, which had contributed to a management shake-up and the resignation of president Akio Tanii and key members of the Japanese team responsible for the MCA purchase. In the fall of 1993, shortly after Morishita was made president, moreover, a bidding war broke out for Paramount, which started him thinking about whether he should cash in his Hollywood chips. Most important of all, he discovered that the vaunted synergy between software and hardware had never materialized, and that Wasserman and Sheinberg were now talking as though the future lay not in such low-cost hardware gadgets as digital laser boxes that played music and movies but in giant record companies and in cable and broadcast distribution systems requiring billions more in investment.

In October 1994, Wasserman and Sheinberg, who had already been rebuffed by the Japanese in their effort to buy Virgin Records, flew to Osaka to see Morishita. Their intention was to convince him of the wisdom of launching a joint offer with the American conglomerate ITT to buy CBS from Laurence Tisch, who was reportedly asking $5 billion for his network. Japanese companies are slow-moving, multilayered bureaucracies, and Morishita's aides were not properly briefed in advance by their counterparts at MCA. As a result, Japanese underlings scurried back and forth, while a confused Morishita refused to come out of his office and greet Wasserman and Sheinberg. The pair of proud and powerful Hollywood titans were left in the humiliating position of waiting for hours in an anteroom.

When Sheinberg got back to Hollywood, he composed a scathing letter to Morishita's boss, Masaharu Matsushita. "Sid wrote the letter because Lew was furious, but would never have said anything, and Sid had to protect his honor," said a high-ranking executive at MCA, who saw the letter before it went out. "In effect, the letter said, 'I have to protest the conduct of Mr. Morishita. He deliberately and willfully insulted Lew Wasserman. He's not entitled to insult a man who has done what Lew Wasserman has done.' Lew read the letter and approved it, although he had Sid tone it down."

"I did send a letter to the chairman after the now infamous trip we took to Japan in connection with a proposed investment," Sheinberg told me. "We were given all the reasons in the world why it was inappropriate even to present it. I thought we were treated excruciatingly rudely, and I said so."

"Sid will never admit it," said a source at MCA, "but I believe that he wanted to bring the situation to a head. By now, don't forget, we were in the midst of Sony's travails with their Hollywood studio, and the one thing we know about Matsushita is that they are extremely sensitive to and paranoid about Sony."

Sheinberg demanded a meeting with the top brass of Matsushita, and it was scheduled to be held in Hawaii, until the press got wind of it, at which point the venue was secretly switched to San Francisco. The Americans gave the Japanese an ultimatum: Grant us total control of the company or we will quit. "Sid was playing a giant game of poker," said the MCA source. "He was betting that Matsushita wouldn't risk losing MCA's top management, who would take DreamWorks along with them."

n November 2 of last year, a Matsushita executive reached investment banker Herbert Allen, the chairman of Allen & Company Inc., who was in the airport in Nairobi, where he had just finished an African safari, and asked him to fly to Japan to give Matsushita a thorough assessment of its options. The Japanese did not initially call Michael Ovitz of Creative Artists Agency, whom they held in high regard, because they thought he might have a conflict of interest; Ovitz represented Spielberg, and the Japanese feared that if Spielberg learned of a pending sale he would feel obliged to tell his mentor, Sidney Sheinberg. But Allen insisted, "I can't get involved in this without Mike." And within a month Ovitz was in Osaka, where he personally apologized for the way the Japanese had been treated by Wasserman and Sheinberg.

Soon Matsushita had four American companies looking at its Hollywood problem: the investment firms Allen & Co. and Goldman Sachs, the talent agencycum-advertising agency-cum-deal-maker CAA, and the law firm Simpson Thacher, which was driving the transaction. Significantly, all of them had close relationships with Seagram, which raised the ticklish question of whether that ultimately gave the Bronfmans an inside track.

"We knew they were looking at the books," said a top executive at MCA, "but we didn't know that it was in connection with a sale. We thought they were just looking at their various options— bringing in a strategic partner or making a major investment. . . . During all of this, Sid refused to believe that Mike Ovitz would be involved in anything without telling him. He kept on saying, 'Mike would never betray me, he'd never do this to me.' And David Geffen—there's no love lost between him and Mike Ovitz—kept telling Sid, 'Don't be naive.' "

"I felt obliged to tell Sid," Ovitz told me, "but I had a confidentiality agreement with Matsushita. And I had given Edgar my word that everything would remain confidential. There was no deal yet. Everything was still in the talking stage. What could I do? Ultimately, I'm a businessman bound by a code of ethics. It was a torturous experience."

In January, after Allen & Co. and Goldman Sachs had completed their evaluations, Ovitz went back to Japan, taking with him Sandy Climan and others of the same top CAA team he had used five years before to advise Matsushita on its purchase of MCA. In the course of a nine-hour meeting, they made a fourhour bilingual presentation with charts and graphs. The Japanese listened, and were impressed, but they did not commit to selling MCA. Of the half-dozen names the Ovitz team gave them as possible buyers, they kept asking, "Who can close?" And Ovitz told them that the Bronfmans could cut a check. Eighteen hours after Ovitz left, Japan was rocked by its worst earthquake in 70 years.

In New York, Stephen Banner, the former Simpson Thacher attorney who now worked for Edgar Bronfman Jr. as Seagram's senior executive vice president, started picking up signals that MCA was for sale. "There were certain things we couldn't talk about, and Steve honored that," said Harold Handler, Simpson Thacher's chief tax expert. "But he was aware of the fact that Matsushita was conducting a review, and that we had been retained. That had been published in the trade journals. There were some very appropriate conversations that, if and when there was an opportunity, Seagram might be interested. And of course we said that if the time comes when there is an opportunity to talk we'll let you know. Steve had his own relationship with people at Matsushita, who were still involved with the MCA relationship. There was a lovely guy named Kaoru Takada, a Matsushita lawyer. And Kaoru and Steve had a conversation sometime at the beginning of 1995."

By late January, Bronfman recalled, "Steve telephoned me and said, 'There's someone coming to visit me from Matsushita, a guy I know named Takada. It would be nice for you to pop in and say hi.' "

On February 27, Banner got in touch with Stephen Volk of Shearman & Sterling, and hired him to represent Seagram. On March 2, Banner, 56, who had a wife and four children, checked himself into New York University Medical Center. He had been diagnosed with lung cancer. Eleven weeks later he died.

'If Seagram was going to be a company in control of its own destiny," Bronfman told me, "then I was convinced that we could and should make this deal. By March 24, we had put together an offer letter and were going to send it to Japan. Conventional wisdom was that the Japanese would need time to talk to their advisers and then get back to us. I felt that I should go to Japan and explain the proposal. There were parts of the proposal that were difficult to put into words, and I felt that the personal relationship I had established with Morishita would be critical to coming to an agreement."

A fierce debate broke out among Bronfman's advisers over whether he should go to Japan. Ovitz, who knew the Japanese best, was in favor of personal diplomacy, and his influence carried the day. Bronfman arrived in Osaka on March 26. He was served club sandwiches and potato chips, and informed that his bid of under $7 billion was not high enough.

"My second trip was all about building trust and confidence," Bronfman said. "But shortly afterwards the rumors started to fly. This was bad news. From Seagram's point of view, it could create what we had sought to avoid—an auction."

On April 6, Seagram sold nearly all of its 163 million shares back to DuPont for $8.8 billion. That same day, Lew Wasserman was asked to comment on the impending transfer of ownership of MCA. "I have no idea," said Wasserman, making one of his rare public comments, "because no one has called me. I've heard nothing."

At eight o'clock in the morning on Sunday, April 9, two Gulfstream IV jets left White Plains, New York, for Santa Monica, California, with Edgar Bronfman Jr. and his advisers on board. At about the same time, another Gulfstream IV, with Edgar Bronfman Sr., left an airstrip in Virginia, near the Bronfman farm, and also headed for California.

By 2:30 in the afternoon, as the lawyers and advisers for the two sides began to assemble in a conference room of the Los Angeles offices of Shearman & Sterling, Herbert Allen arrived from his ranch in Wyoming, wearing cowboy boots, and Michael Ovitz, tanned from a cruise in the Bahamas, went down to the lobby to greet Morishita and the Japanese contingent. The two Edgars went into a nearby office and closed the door behind them. Senior called Wasserman and told him what was about to happen; Junior tried to reach Sheinberg, but couldn't get through to him. A few minutes later, formal papers were being exchanged on the 20-foot-long conference table, and as Edgar senior looked on, his son signed his name.

Edgar junior's first order of business was to find someone to replace Wasserman as chairman of MCA. The 60-year-old Sid Sheinberg was not in the running to fill his mentor's colossal shoes, and he didn't bother to seek the position. "Sid said, 'I don't want that job,' " Bronfman told me. "He said, 'I want to do something else.' I told Sid that I would like him to remain associated in some capacity with MCA, and until he and I got that settled and out of the way I wasn't ready to move on filling the top job."

Hard-nosed Hollywood executives found it hard to believe that Bronfman had bought an entertainment company for nearly $6 billion without having a clear idea of who was going to run it. But, in fact, that was precisely the case. "When you're going through these deals, reality is suspended," he told me. "There is a moment in time when either you make a deal or not. It's easy to sit back and say you should line up management. This was a unique opportunity to buy a great asset at a favorable price, and there wasn't time to line up management. . . . It's not going to make a lot of difference to our shareholders whether we have new management on day 1 or day 91."

With the question of management left up in the air until after due diligence was completed and the sale was final, the Spielberg-Katzenberg-Geffen team abruptly suspended negotiations over a future distribution deal with MCA. David Geffen was telling everybody that the likeliest choice for the new top man would be Michael Ovitz. Yet near the end of May, Bronfman told me, "Mike is unique. I talk with him every day. But I haven't talked to him about management."

Ovitz, as always, was keeping his own counsel, though he confided to close friends, "The truth is, I have done absolutely nothing regarding this job, and yet the whole world's talking about it. It's a big hoot." He was less amused by the suspicion that his competitors, in an apparent effort to destabilize CAA, were spreading rumors that a handful of top young CAA agents were on the verge of leaving his company.

There were many in Hollywood who believed that Ovitz was the only serious candidate, and that if on the remote chance Bronfman didn't get him he'd opt for a prestigious name from outside the movie community. "If I were Bronfman putting all that money in there," said one former studio head, "I'd want a wow choice, and Mike is clearly the most exciting possible choice." According to this line of reasoning, Ovitz has grown tired of being at the beck and call of immature superstars with overgrown egos, and wants to follow in the path of his idol, Lew Wasserman—the gold standard in Hollywood. What's more, the men in the movie industry whom Ovitz respects—billionaire David Geffen and near billionaires Michael Eisner and Steven Spielberg—have amassed far larger fortunes than his, which is estimated at about $100 million. It is said that the time is ripe for Ovitz to cash in his halfownership of CAA, which could bring him more than $200 million. At MCA, moreover, Ovitz would have the opportunity to replicate Michael Eisner's experience at Disney and also make hundreds of millions of dollars more in rights, options, warrants, and bonuses. A potential snag: anyone buying CAA would deem it of less value without Michael Ovitz.

Before Ovitz and Bronfman could make a deal, there are two major precipices that they would have to cross, according to those familiar with their thinking. First, Ovitz would have to decide whether he wanted to walk out the door of CAA, perhaps taking with him his right-hand man, Sandy Climan. For his part, Bronfman would have to decide how much he could afford to give Ovitz, from both a financial and power point of view. "It all comes down to a supply-and-demand issue," said a person in a position to know. "There's a very limited supply and a great demand for the heads of these huge entertainment companies."

But others felt sure that, in the end, Ovitz would not go to MCA. "I don't think he will take the job," said an Ovitz confidant. "At CAA, he is king. At MCA, he would only be the prince. At MCA, Mike would be more exposed. There are many people in this town who don't like him, and want to get him. ... At MCA, his power would be circumscribed, and he wouldn't be as protected as he is now. He would be more vulnerable to attack."

"Money for Mike is not the issue," said someone who was familiar with his thinking. "If net worth were the issue, Mike would have chosen a different career path a long time ago. Keep in mind, Mike has many options other than MCA."

Perhaps the most tantalizing option for Ovitz would be to raise about $2 billion in order to buy the 14.9 percent Seagram ownership of outstanding Time Warner common shares, which would put him within striking distance of controlling the company.

"This issue of who runs something is always a difficult one, because you get into very small indices, and semantics, and you have to be very careful," said Barry Diller, who has taken himself out of the running for the MCA chairmanship. "Edgar isn't going to move to Los Angeles and quote run unquote MCA. He isn't going to go to dinner at Hollywood restaurants and be in meetings with writers, directors, and actors. But he will be the senior officer. Anything other than that is unrealistic and just babble. He's the senior executive officer of the company, and he will function as such, nomatter who it is that reports to him. I don't think there is any question that Edgar Bronfman Jr. is going to deal with his responsibilities."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now