Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowPlaying Jane

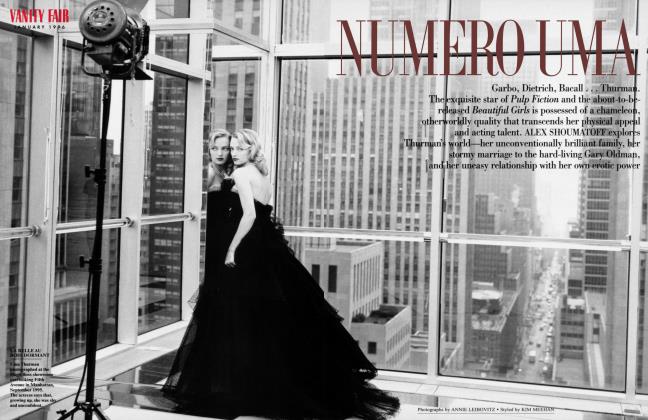

Right now, the hottest writer in show business is not John Grisham or Michael Crichton, but Jane Austen. The BBC is following its movie of Persuasion with a television adaptation of Pride and Prejudice, Emma Thompson has done a film version of Sense and Sensibility, and there are three Emmas in the works. LAURA JACOBS screens the novels

LAURA JACOBS

If Hamlet is the first son of English arts and letters, Elizabeth Bennet is the daughter most dear. Female readers of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice immediately see themselves in the second sister. Not the angelic eldest, Jane, but the next girl, the one with fine eyes and spirited seeing. She is her father's favorite—"Lizzie has something more of quickness than her sisters"—and her author's favorite, too: "I must confess that I think —her as delightful a creature as ever appeared in print." Even Mr. Darcy, the man who slights Elizabeth within the novel's first pages, soon concedes that she is rendered "uncommonly intelligent by the beautiful expression of her dark eyes."

To film Pride and Prejudice you need a perfect Lizzie—a bit of casting magic akin to the search for Scarlett, another heroine who was not your typical beauty. Hope and apprehension do battle as we await the first glimpse of a new Elizabeth, and in the six-hour BBC adaptation of Pride and Prejudice that airs this January on the Arts & Entertainment cable network, we do not wait long. The credits roll, a hunting horn sounds, two men on horseback survey an estate, a young woman watches from a hill. With her face snug in a straw bonnet, she's a pink-cheeked miniature released from a locket, almondeyed and surrounded by sky. A scene later, when we hear her speak the novel's famous opening line—now said as an amused aside to her sisters—it's in a red-rose voice, surprisingly deep-toned, lush-layered, potentially thomed. Jennifer Ehle's Elizabeth is irresistible.

Indeed, this Pride and Prejudice, directed by Simon Langton, has become the highest-rated costume drama in BBC history, an event of runaway momentum that pulled in audiences of more than 11 million regularly. For weeks U.K. viewers risked speeding tickets as they raced home to the telly. Newspaper articles wondered anew (and rather anachronistical ly) if women always marry for money. Literary laureates wrote their Reconsidering Austen articles. Even Private Eye addressed Jane mania. Pitting Pride and Prejudice against its time-slot competition, the existential cop show Cracker, the magazine published a chart that showed "How They Shape Up": Pride rated three zeros for rape, murder, and assault with a chisel to Cracker's sum total of eight, and contained 17 quadrilles to Cracker's none.

Those zeros are no small part of Austen's appeal. Coin of the Realm right now, she's a prime-time English export that includes, along with the BBC Pride and Prejudice, an earlier BBC adaptation of her Persuasion, released in theaters in the U.S. last fall, and actress Emma Thompson's accomplished adaptation of Sense and Sensibility, opening this month. An Emma-fest follows, with three treatments in the works for 1996 and '97: Miramax is currently filming a version that stars Gwyneth Paltrow, Greta Scacchi, and Juliet Stevenson; Britain's ITV is producing a two-hour film; and the BBC has a five-part serialization planned. John Grisham, Michael Crichton, remove your hats: the hottest property in town is a writer who could barely get a byline. Austen's first novel, Sense and Sensibility, was signed: By A Lady.

For most of us, MGM's Pride and Prejudice of 1940 is the primary point of reference, our first experience of Austen on film. The movie opens with the titles "It happened in OLD ENGLAND ... in the village of Meryton ... ," but one glance at Ye Olde sets shows we're in the glycerin hills of Hollywood. Costume designer Adrian sets the wonky tone with historically incorrect crinolines straight out of Little Women, surreal hats like imploded hatboxes. Aldous Huxley and Jane Murfin's screenplay isn't shy with liberties, either. In this script "Every savage can dance" becomes "Every Hottentot," and it's fun to hear Laurence Olivier's Darcy hit all four t's. Looking gorgeously out of sorts, as Darcy would, he delivers his lines with a violin quiver of condescension. On the other side of the Actors Guild map, Maureen O'Sullivan's Jane Bennet practically twangs her lines, and Greer Garson—Elizabeth Bennet Forever—Glinda-glides from scene to scene as if on casters, not so much acting as advertising her eternal twinkle. It's Austen in Oz, which is to say, a hugely entertaining purist's nightmare.

(Continued on page 122)

To film Pride and Prejudice you need a perfect Lizzie.

(Continued from page 76)

The current crop of Austen adaptations reflects our era's interest in authenticity, a standard embodied in classical music's original-instruments movement, in the cleaned ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. The BBC productions of both Pride and Prejudice and Persuasion rub away the waxy buildup of preconceived performance, and the pendulum takes a corrective swing to the nature state. Persuasion shows us crumbs on tables and weathered hems, chalk complexions and crow's-feet creeping into view. Pride and Prejudice moves outdoors, on location, too, though with less sense of hazard, more blue air and sun and simple pleasure.

The Bennet girls—bosoms perched high by Regency corsets—play horseshoes, stroll the parks, trip into town.

Elizabeth, when alone, loves to run.

"Our Pride and Prejudice is more fluid, more filmic, than previous BBC versions, which were done mostly in the studio," says Andrew Davies, the man who adapted Austen for this series (and, before that, BBC's Middlemarch last spring). It didn't hurt that the production was conceived as six hours. Unlike Huxley and Murfin, whose script he admires for its compression into 118 minutes, Davies did not often alter Austen's dialogue, contenting himself with cuts and adjustments of vocabulary, writing small interpolation scenes only when necessary. "One could get the whole story and could even add bits by going into flashbacks," Davies explains. "Pride and Prejudice is a very speedy book. People think of Jane Austen as being sedate, but the story just crackles along. You do a really bad job if it feels slack, because there's always some surprise or reverse. I had to be firm about resting the pace, to allow the characters a little lull where they are just moving about doing their little tasks."

Those little lulls are part of the series's special grace, long looks in which to savor Ehle's Elizabeth, her mahogany ringlets, her sidelong considerations, her quick coloring as a shock or snub rounds the corner. She's mercurial and maidenly at once. But then, Ehle—the daughter of American writer John Ehle and English actress Rosemary Harris—admits a similarity between the dialogue of Austen and Shakespeare, where "the meaning of the line comes at the end," requiring dexterous understanding. Susannah Harker's Jane is more legato, a swan-necked, Sauterne beauty, and Julie Sawalha (Saffy from Absolutely Fabulous) is the saucy, snorting, lovably awful Lydia. As for Alison Steadman's squawking parrot of a mother, Mrs. Bennet, we feel the mortification she inflicts as if it were our own. And then there's Mr. Darcy.

It was Olivier who set the precedent for Darcy as Melancholy Dane. His "It's no use" proposal to Elizabeth is a stunning soliloquy, and brings a muchneeded erotic ember to the 1940 film. Still, it's a matter of record that Olivier was unhappy with the director's treatment of Darcy—in close-ups the camera favored Elizabeth by a ratio of 20 to 1. There are no such insults in the BBC production; its creators especially sought to develop Darcy. "We've concentrated quite a bit more on the men, and tried to write some things that Austen didn't write about what Darcy was doing while Elizabeth wasn't on the scene," says Davies. "When he goes back to his aunt's after his disastrous proposal to Elizabeth, all upset, we go with him. We sit up all night with him while he writes his letter, and we go into flashback with him about his early childhood and his young manhood." The payoff of such expansion is a romance of better blossoming. The risk, Davies confesses, is that of making Darcy less mysterious. With pulse quickener Colin Firth in the role, no need to worry. His Byronic brooding, his miserable isolation at Meryton assemblies, evolve into pure longing, a grave tenderness at the sight of Lizzie. Davies laughs, "If you can get Darcy right, he's just about the sexiest hero in British literature."

And anyway, mystery is not the player in Austen plots that Withheld Information is. Secrets sit like black holes in the drawing room, revelations that will turn reality into abyss. And they give the lie to the notion that Austen is a cozy writer. (Her own family may have had something to hide: recent evidence suggests that Jane's reverend father buttressed the family income by smuggling drugs.) Actually, Austen is in tune with today's mantra: Knowledge is power. Perhaps that's why last summer's Clueless, a 90210 update on (what else?) Emma, was such a natural fit—the plastic pastoral that is Beverly Hills could be Austen in overdrive. Intellectuals have long fought the coziness quotient, none more patiently than Lionel Trilling. He understood, without approving, that readers mistake Austen's focused field of invention, her aesthetically complex idylls, for hearthy charm.

Jane Austen is in tune with today's mantra: Knowledge is power.

In filming Sense and Sensibility, Ang Lee, whose previous credits include Eat Drink Man Woman and The Wedding Banquet, was keen to avoid the curse of cozy. He does not care for the 1940 Pride and Prejudice because it is so unchallengingly light and doesn't quite skirt sentimentality. Lee's vision of Austen's England is pictorially opulent, symphonic in scale, yet powerfully raw and unprotected (he feels Britain's early19th-century transition from feudal society to modernity parallels that of Chinese society today). Where the BBC Pride and Prejudice is buttery-hued, with top notes of canary, ivory, and persimmon, Lee lets the colors of the Devon countryside dominate, and they come on aggressively, in sheets of blue gray, gray green, spanking white. We feel the chill sea air, hear wuthering heights in the distance. Salt mist gathers into thunderheads and hearts. Gritty shadows—inspired by the Dutch-master paintings Lee saw in English manor houses—hang in the camera frame's corners, watching for ruin.

Lee was chosen to direct as much for his wit as for his eye, and the film's mighty atmosphere is matched by concentrated character observation. Duality is everywhere, Lee points out, starting with the author herself—"Austen is a combination of sharp satire and emotional drama"—and continuing in the book's title: "It's usually seen as sense being Elinor and sensibility Marianne. But I think everybody has both in them. It's an irony that Elinor marries for romance and Marianne for righteousness." Even the posture of the time contained a contradiction: "The sense of deportment had a very passionate spirit underneath." And so plumed puns and explosions of farce ride alongside sadness and stoicism. Lee worked closely with Emma Thompson, who wrote the screenplay in 1992 after she filmed Howards End. Thompson loosens up the language and slips into contemporary rhythms—the dialogue has something of her own openness.

"Keeping balance," repeats Lee. "It's really about personal will set against the rest of the world. It's about maturity, and how you find happiness." Austen's novels are founded on doublings and reversals, compositional strategies that bring symmetry to her stories, creating a self-contained, morally weighted world capable of righting itself in a storm. In this she is like Mozart (who has, ad infinitum, been dressed up and dressed down, deconstructed and restored). In fact, in Mozart the Dramatist the late English critic Brigid Brophy could find no higher peer for the beloved composer than Austen.

Both abided by the "clarity, form, and wit of the enlightenment." Both directed their genius to seeking peace between opposites, be it sense and sensibility, duty and desire, nature and artifice. "Jane Austen is not dazzled by her heroes and heroines for an instant," Brophy wrote. "Not being infatuated, she is free to like them, and she prefers to save rather than drive them to a romantic damnation." With romantic damnation the cinematic norm (hey, how about another vampire movie!), it's little wonder there's an appetite for Austen's principled omniscience. She's correcting the balance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now