Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe ringside epiphanies of longtime Daily News photographer Charles Hoff, preserved in a new book, The Fights, lead GAY TALESE to examine the visceral allure of boxing

November 1996 Gay TaleseThe ringside epiphanies of longtime Daily News photographer Charles Hoff, preserved in a new book, The Fights, lead GAY TALESE to examine the visceral allure of boxing

November 1996 Gay TaleseFighters in the ring taste one another's sweat, breathe one another's air, smell the emanations rising from one another's guts; they lean their chins on one another's shoulders while administering body blows, occasional head butts, even neck bites. It is an intimate experience. only a few cuts above cannibalism, involving self-perpetuation and survival.

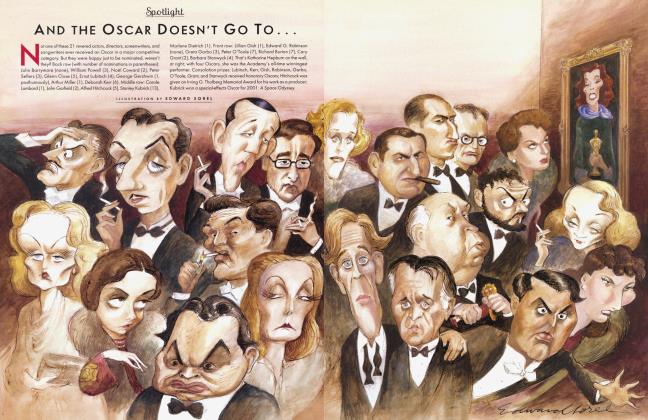

Every fighter's face bears the marks of other men and carries in each battered bone and trace of scar tissue a history of challenges met. prices paid, and fears overcome. It is little wonder that writers and other solitary artists and craftsmen are drawn to these most naked of athletes. Among the photographers who have truthfully depicted the graceful and terrifying choreography of the sport is the late Charles Hoff.

A feisty little man of five feet six inches from Coney Island. Charles Hoff parted his hair in the middle and usually arrived for assignments wearing a bow tie and sometimes a Stetson. He worked from 1935 to 1968 as a staff photographer for the New York Daily News, where he adjusted himself and his lens to thousands of newsworthy situations—parades, political debates, labor strikes, murders, fires, and such spectacular disasters as the one in 1937 that would launch his career and that would return to the headlines decades later in the announcement of his own death.

That headline read, CHARLES HOFF DIES: HINDENBURG PHOTOG. The crash of the 804-foot German dirigible, in which 36 passengers burned to death in the sky over New Jersey, was an event that Hoff observed and photographed so memorably that it would transcend everything he would later do with a camera—until the publication this month of The Fights, a collection of Charles Hoff's boxing photographs, which reveals his special affinity for the sport and his talent for anticipating the destructive moments of some of its most aggressive competitors.

All images are from The Fights: Photographs by Charles Hoff, edited by Constance Sullivan, essay selection and introduction by Richard Ford, with a biographical essay by Richard B. Woodward: to be published in November by Chronicle Books.

Every fighter's face bears the marks of other men.

From his ringside seat. Hoff would watch the movement and positioning of each fighter's feet. From the feet he could tell, in advance, when a heavy punch was about to be thrown. To get the closest shots possible, he would duck his head under the ropes of the ring and stretch his neck as far as it would go. His timing was such that he not only caught the receiving fighter's facial response to the blow, but also often showed the reactions of the surrounding spectators. One evening in 1967, during a semifinal event of the Golden Gloves at Madison Square Garden, a fighter was knocked out of the ring and landed on top of Hoff. The photographer's health was so affected by the assault that his career was essentially ended. He retired from the News the following year.

Now, more than 20 years since Hoff's death, his ringside camera work is suddenly being celebrated as it never was during his lifetime. Photo critic Richard B. Woodward writes in his biographical essay in The Fights: "The high quality of his work sets it apart from most sports photographs of the period. In fact, his boxing photographs are as impressive as any single body of work produced by an American from the late 1940s to the mid-1950s. While serving as an almost weekly record of the sport at the peak of its popularity (then second only to baseball). Hoff's photographs have a startling angularity and coherence that look forward to the frame-bending experiments of Winograd and Friedlander during the 1960s and 1970s."

The Fights presents more than 40 of Hoff's photographs of such champions as Joe Louis. Rocky Marciano, Jake La Motta, and Sugar Ray Robinson. It also contains a portfolio of boxing essays selected by the novelist Richard Ford, including Ford's own memory piece. Woodward's essay, and work by A. J. Liebling, Jimmy Cannon, and James Baldwin. They are among the most astute commentators on this sport, where fans pay money to sec pain and suffering, and where the financial welfare of the participants depends on how well they satisfy their audience's appetite for brutality. Charles Hoff's themes are timeless, rooted in caste and social constructions. The world he shows in his photographs still exists, reflecting the values he so dramatically explored.

Last July, in Madison Square Garden, dozens of impassioned fans broke chairs and instigated fistfights among themselves after witnessing a bout in which Riddick Bowe, a black heavyweight who had once been champion, was overwhelmed by Polish underdog Andrew Golota, who had entered the ring with a reputation as a relentless brawler and flesh biter.

Golota did not bite Bowe that night. But he did double him over with so many below-the-belt punches that the referee, whose threats of disqualification Golota had repeatedly ignored, finally awarded the decision to the fallen figure of Riddick Bowe, who had just collapsed to the canvas from the effects of yet another foul blow.

Numbers of riotous fans—some were Bowe's partisans who were inflamed by Golota's malevolence toward their exchampion, others were Golota's supporters—were later arrested by the police for disorderly conduct. One of Bowe's cornermen would also be discharged from his job because he participated in the disturbance. (He hit Golota over the head a number of times with a walkie-talkie, although the stalwart Golota hardly seemed to notice.)

While boxing's official record book now identifies Andrew Golota as the loser to Riddick Bowe, the notoriety that Golota achieved at Madison Square Garden has greatly enhanced his career. He has emerged from relative obscurity to join the ranks of fighters who can provide fans with what so many of them want to see—pain and violence. Since he was not suspended or even fined for his infractions, his handlers lost no time in negotiating a rematch, which will occur this December, and which will surely enrich Golota as never before.

Furthermore, because of his skin color, Golota qualifies to join boxing's long list of "White Hopes," a category of contenders who have usually proved disappointing against black champions. But as a marketing idea in a racist society, the notion has lasting appeal. The fighters themselves are rarely prone to racial or ethnic prejudice. Their boxing camps are pQpulated by individuals of all colors and creeds who live together, eat together, work out together; whatever animosity is verbally expressed by opposing fighters during pre-fight interviews is invariably done at the direction of promoters to arouse fans.

Fighters are impersonators. They are usually men of the underclass who are among the most fearless and desperate of their kindundereducated and close to unemployable except when expressing with their bodies the killer instinct that exists in multitudes of their followers who have few legal outlets for their fury except during wartime, or the hunting season, or when yelling out their instructions in a noisy boxing arena. The competing fighters in the ring are two lightning rods through which the dangerous currents in the surrounding atmosphere are channeled, and by which the society at large usually protects itself from the potential uncontrollable rage of a dissatisfied and frustrated public. On the night of the Bowe-Golota event, when the Madison Square Garden security measures were far from adequate, there was the rare occurrence of the fans' being better matched than the fighters.

But prizefighters, with few exceptions, are the least hostile of athletes. Unlike baseball players, who have been known to jump into the stands to assault heckling fans or to throw balls and other equipment at critical members of the media, the typical fighter responds to the crowd's boos and to a negative press in the manner that Golota displayed when being clobbered over the head with a walkietalkie—with equanimity. Young amateur fighters do not grow up being coddled and spoiled by the type of protective system that accompanies the most talented of high-school and college athletes in other sports. Yet despite all the blows and blood that fighters often exchange in the ring, at the conclusion of the ordeal there is a convincing sense of warmth expressed by their customary embrace.

Charles Hoff's work is attentive to every nuance of meaning occurring in the ring. But it is the spirit, the humanity, the grace of the fighters themselves that animate the photographer's eye. It is the desire of the fighters themselves that fills the frame and that oftentimes goes unrecognized.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now