Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

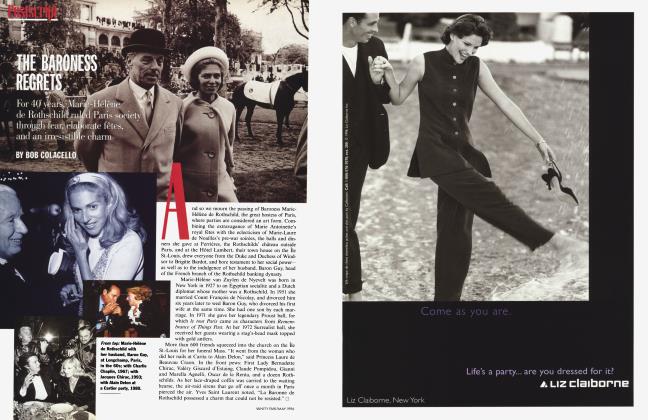

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFRANCE'S GILT COMPLEX

Behind the newly gilded splendors of Paris and the glamour of its couture shows, France is literally and figuratively bankrupt

ANDREW NEIL

Letter from Paris

n the night of Jacques Chirac's presidential victory last May, Paris was a party. Young people drove around in their cars waving the tricolor and tooting their horns while others danced in the streets and drank into the late hours of a hot spring night. Fourteen years of increasingly sterile socialism had been ended. A new dawn of conservative realism beckoned.

But Chirac had won on a false prospectus: impossible promises to cut taxes, increase government spending, and raise salaries— all in pursuit of higher growth and more jobs.

"We knew he was talking nonsense, but the country wanted a change," i says Christine L Ockrent, editor of I L'Express magazine. (She lives with Bernard Kouchner, a former Mitterrand Cabinet minister.)

For months after the election Chirac's government was frozen like a rabbit transfixed by the headlights of an oncoming car as it came to terms with the harsh realities of power: higher taxes, cuts in public services, frozen pay—the opposite of what he had promised on the campaign trail.

Usually it takes the French a couple of years to turn on those they have elected. With Chirac and his prime minister, Alain Juppe, it took only a couple of months. The fall from grace was fast and far: by late last summer, polls were already showing them to be the most unpopular president and prime minister in the 40-year history of the Fifth Republic. "The facts have boomeranged back very quickly to hit them," comments Ockrent.

France has a love affair with medicines because the country is a utopia for hypochondriacs.

The unions took to the streets even before Chirac and Juppe had screwed up the courage to renege on their fanciful election promises. A general strike paralyzed the country last October 10. Protesters marched through Paris chanting, "This is just the beginning." They were not kidding. More strikes and disruption greeted Juppe when he eventually announced an austerity package in November. In early December, France ground to a halt. Seventy miles of traffic jams turned the French capital into the world's largest parking lot as train and bus strikes forced workers to commute by car. The more adventurous tried cycling, rollerblading, or even hitchhiking: the main boulevards in and out of town were crammed with desolate folk trudging in the snow while holding little placards stating their destinations in the hope of catching a lift from somebody in the crawling traffic.

Christmas cheer was hard to find. Empty department stores closed early each day, reporting the worst Christmas sales in modern memory. Some hardships were typically French: supplies of foie gras dried up as deliveries ceased. Others were more basic: panic buying of essentials was widespread as rumors grew that Paris was about to run out of flour and sugar.

French TV news this winter has been dominated by pictures of marching strikers, idle railways, grounded planes, burning cars, and out-of-work kids throwing bricks or Molotov cocktails.

A government which had done nothing at all to prepare public opinion for its harsh U-turn had to face a remarkable reality: despite the hardship and dislocation, opinion polls showed that most Frenchmen actually sympathized with the strikers. The left-wing Le Monde and the right-wing Le Figaro both suggested that even the British coped with change better—conclusive proof that France really was in crisis.

ander around Paris on a sunny, brisk winter's day and it's hard to imagine you're in the capital of a nation in disarray and decline. What was already the most beautiful major city in the world has had a face-lift. From Notre Dame to the ChampsElysees the city center has been given a good scrub. The result is stunning.

But then, no expense has been spared. Not even Louis XIV, the autocratic Sun King, spent as much as Francois Mitterrand, the Socialist Sun King, who finally stepped down as president in 1995 after 14 years. He painted the town gold—literally.

The 18 rostral columns around the Place de la Concorde have been gloriously regilded; so have the angels at the approach to the adjacent Tuileries Gardens, which itself is the beneficiary of a $55 million restoration. Across the river the Institut de France, home of the Academie Frangaise (the country's cultural thought police, who try to deter French folk from using such foreign cognates as le weekend), has new gold leaf on its dome. The dome of the Invalides, farther down the Left Bank of the Seine, is now covered with 555,000 sheets of 24-karat leaf.

But all this represents only the small change spent on the refurbishment of Paris. The big money went on Mitterrand's grands travaux, which included renovating the Louvre ($1.25 billion, including I. M. Pei's glass pyramid), a new National Library of four L-shaped towers in the eastern part of the city ($1.5 billion), a new Bastille Opera, a $200 million modernistic music complex in the northeast, and the great glass-andsteel arch of La Defense, roughly twice the size of the Arc de Triomphe.

Mitterrand spent more than $6 billion to restore and recast Paris as the undisputed capital of the European Union. It was typically French thinking on a grand scale, uninhibited by considerations of cost. It is all the more remarkable when you consider that France is broke.

T he average French bathroom is I crammed with more medicines than I an American drugstore. Typically, Frenchmen visit their doctors eight times a year for 37 prescriptions; they take five times as many pills and potions as the British.

Not that the French are any less healthy than the rest of us. The country is simply a utopia for hypochondriacs.

No matter how minor a Frenchman's ailment or how insatiable his demand for pills, the government will pick up most of the tab. He can go to six different doctors a day and the state will still reimburse him for every prescription.

In last year's presidential elections, almost 40 percent of the voters opted for the loony-tunes of French politics.

It is part of a cradle-to-grave socialwelfare system that is among the most generous in the world. Once the glory of France, it was paid for by the postwar boom. In these more stringent times it has become an albatross: the cost is

crippling the economy. But weaning the French from their addiction to welfare is no easy matter.

The French welfare state is financed by massive payroll taxes, which means that if you employ somebody at $10 an hour you have to pay the state an extra $5—and then it's almost impossible to fire him. With such incentives

not to hire, no wonder the rate of French unemployment, at almost 12 percent, is more than twice that of America.

Yet, despite this punitive tax on jobs, the country's budget deficit is out of control: there is an accumulated deficit in the

welfare fund of $50 billion, and every year it has to borrow another $12 billion to meet the bills. "We can't go on racking up this debt," says Ockrent. "We'll end up like a Third World country."

The politicians have been scared to take drastic action because of what one British diplomat described to me as the French elite's "innate fear of rocks being thrown." This fear turned out to be legitimate: when Chirac and Juppe finally acted, rocks were thrown. Every generation or so, French politics is decided in the streets. The idea that France is again on the brink of one of these periodic revolutionary flurries has produced a collective nervous breakdown at the heart of French government.

11 should have been a glittering evening I late last September. The venue was the I Palace of Versailles. The guests were, quite simply, the people who run France. The occasion was the 50th anniversary of their alma mater, the Ecole Nationale d'Administration (ENA), the most prestigious educational establishment in France, which every year churns out the small number of graduates who will reach the commanding heights of French government and business.

There were cocktails on the Apollo Terrace, a light buffet in the Orangerie, dinner in the Gallery of Battles, a concert in the Royal Chapel, even a disco in the palace apartments.

The alumni of ENA, known as enarques, dominate the top jobs in France. Chirac is an enarque, as are eight of his ministers, including Alain Juppe, who succeeded Edouard Balladur, another enarque, as prime minister; even the leader of the Socialists, Lionel Jospin, is an ENA graduate.

The enarques have gradually colonized the top posts in the civil service and moved on to be captains of industry in telecommunications, banking, and transport, where the state is still pervasive. Their control of France almost total, they were entitled to feel they had earned the right to celebrate their anniversary in the opulent setting of Versailles, especially since they are not an upper class but a genuine meritocracy. But something was wrong.

Many chose not to wear the tuxedos normally mandatory for such occasions. The decision was made not to illuminate the beautiful Versailles gardens lest too much populist light be cast on conspicuous consumption by the elite. Worst of all, Chirac and Juppe were no-shows.

The festivities were subdued because the party goers sensed that France is today deeply disillusioned with its governing classes. In the first round of last year's presidential elections, almost 40 percent of the voters turned their backs on the mainstream parties and opted for the loony-tunes of French politics, from neofascists to Trotskyites. It was a chilling warning of possible things to come. Alain Madelin, Juppe's first finance minister, who was forced to resign within months of taking office for being too honest about the tough medicine France would have to swallow, has said the country is witnessing the rejection of an elite comparable to the events leading to the French Revolution of 1789.

All the mainstream parties are officially behind la pensee unique (single thought): that France's future is alongside Germany in the driver's seat of the European Union. The keystone of this policy is the franc fort (strong franc), which is meant to tie the French currency irrevocably to the mighty Deutsche mark.

Since the Germans have invaded France three times since 1870, this is not an ignoble strategy. But the economic costs are high. Vichy France was that part of the country which remained formally unoccupied during the Second World War, but was still very much under Nazi Germany's thumb. The whole of France today is a monetary Vichy, its economic policy effectively determined by Germany.

The overvalued franc is crippling French industry and has created a huge army of jobless, especially among the young, whose unemployment rate is over 20 percent. The 1992 Maastricht Treaty on European economic and monetary union stipulates that countries cannot join the European currency unless their budget deficits are no higher than 3 percent of their gross domestic product (G.D.R) by 1997. France's deficit is currently almost 6 percent.

So the government is taking an ax to public spending to meet the Maastricht deadline for monetary union. But it risks killing off what is already a weak recovery, making the unemployment lines even longer. In pursuit of its European ambitions, the French establishment has built itself a prison from which it does not know how to escape.

4T inish him off, finish him off," W screamed the French policeman I crouching near the badly wounded young Algerian who lay on his back, still holding his gun.

Khaled Kelkal was an unemployed 24year-old from a Lyon suburb whose fingerprints were found on tape linking a detonator to an unexploded bomb on the high-speed train line between Paris and Lyon, France's second-largest city. The interior minister claimed Kelkal had been involved in at least four terrorist incidents. His face had been on 170,000 wanted posters. Now he was lying, close to death, beside a bus shelter outside Lyon.

We may never know if he was the serial terrorist the government claimed, for more shots were fired and Kelkal was dead. A paramilitary policeman ran up to the corpse and kicked it just to be absolutely sure there was no life left in it.

The French government and media were triumphant: the prime suspect in a summer of terrorist bombings blamed on Muslim militants from Algeria, which had claimed seven lives and injured scores more, had been killed. A few voices said it smelled of an official execution, especially when French television refused to broadcast its videotape of the policeman shouting "Finish him off." But nobody much cared: the government said he was a terrorist and he was dead. End of story.

But it wasn't. The bombings continued. Soldiers in battle dress carrying assault rifles are still patrolling the Champs-Elysees. The streets are packed with police and paramilitary units. Trash bins have been removed or closed so that terrorists cannot leave bombs in them. Cars are banned from parking outside schools and other public buildings. Paris is an armed camp.

They rioted in Kelkal's suburb a few nights after he was shot dead-nothing serious, just the sort of mayhem that regularly afflicts France's immigrant ghettos. The authorities say the North African population makes them a breeding ground for the Islamic fundamentalism spilling into France from its former Algerian colony. Others deny that France's Algerian immigrants are in the grip of fundamentalist fervor. Most never even go near a mosque. Nor do they have jobs: in Kelkal's district the unemployment rate is 40 percent, and with current economic policies, jobs are likely to remain scarce. The police patrol such areas, which surround Paris and most other big French cities, in armored cars.

More than 40 percent of the estimated 3.6 million immigrants living in France (6.3 percent of the population) are from North Africa. The French have a successful tradition of absorbing foreigners of all colors. This is a far less racially divided country than the United States, and racial tensions have been relatively rare. Except when it comes to Muslims.

The French fear growing ghettos of Muslims unwilling to assimilate. This is great news for Jean-Marie Le Pen and his neofascist National Front. The National Front is France's main workingclass party, its racist appeal to white voters all the more potent because, at a time of high unemployment, it blames immigrants for stealing their jobs. It scored almost 16 percent of the vote in the first round of last year's presidential elections—twice as much as the Communists—and in its Mediterranean stronghold it has become the premier party of the right.

"The fight is no longer between left and right," says leading French designer Philippe Starck ruefully. "It is confined to right versus extreme right. We are paralyzed: we can't say too much against the present government lest it pushes people even further right. This makes the political situation in France very dangerous. We are opening the door to a Ftihrer."

ou'd think they'd learn to smile before learning to jog with a tray," said an English friend as we sipped a beer on the Boulevard St. Germain. We were watching waiters in a charity race in which they have to run six kilometers with a tray holding a Perrier bottle and three glasses. "I've never seen them move that fast to serve me." Since we'd waited 15 minutes for the beefs, he clearly had a point.

Some things never change: Parisian waiters are as surly as ever. "We're not renowned for being welcoming," one minister has admitted. "Even the most attractive girl needs a bit of makeup to seduce." In that spirit the government has started a "Bonjour" campaign to encourage taxi drivers and others to be more friendly. As yet it has had no impact on the attitudes of waiters.

France is witnessing the rejection of an elite comparable to the events leading to the French Revolution of 1789.

The franc fort means one gets less than five francs to the dollar, which makes this city unbelievably expensive. A coffee in a fashionable sidewalk cafe can cost over five dollars. A small room in the stylish Hotel Montalembert is over $300 a night—breakfast is extra.

France is still the world's most popular tourist destination, and tourism is by far its biggest industry, accounting for 9 percent of its G.D.P., supporting 200,000 companies, and providing two million jobs. But the number of foreign visitors has not risen for three years.

Last year was especially bad: an overvalued franc, terrorism, and protests against nuclear testing deterred many international travelers. The French Riviera had one of its worst years ever—when you can park in August on the Croisette in Cannes, you can be sure the place is in trouble.

The strikes don't help, either. Flights are regularly canceled, airports frequently closed. Driving to the Nice airport one morning last summer to catch a flight to Paris, I heard on the radio that the domestic airline was on strike. So were the trains. The buses were out, too. But at least I could park in Nice: the meter maids were also on strike.

T he Paris pret-a-porter collections reI main a twice-yearly tribute to organI ized chaos. You would think they'd have the hang of it after more than 30 years of practice, but no: Nothing ever starts on time. Shows seem to be specially arranged so that as one ends the next begins—at the other end of town. A pass is no guarantee of getting in: the essential passport is a sharp elbow to force your way through the melee, especially for the collection of John Galliano, who has recently taken up residence at the House of Givenchy, where he is showing his couture collection this January.

His invitation had come in the shape of a red ballet slipper in a chalky box. His show in the historic Theatre des Champs-Elysees has attracted more gapers than the Oscars, a heaving mass of humanity through which the fashionara—clad in regulation black, waving their precious tickets aloft—struggle to pass, for nobody (of course) has thought to clear a path.

Not that there is any rush—the show will start at least an hour late anyway. Once inside one finds a host of ushers with clipboards; none has a clue where anyone's pre-assigned place is. When the curtain finally goes up, half the audience is onstage. Nobody is quite sure if this is a subtle Brechtian touch—or the only place they could find a seat.

The models stream onstage, then up the aisles to mingle with the audience, all fairy tutus and white dresses from the antebellum South, with shells, bones, and leaves sticking out of their hair. They have been told to look lost, vacant, even to simulate minor tantrums. For most models this requires no acting. The lighting is gloomy. It looks more like a scene from A Midsummer Night's Dream than a fashion show.

Then a man with brown Rasta-looking hair and wearing scruffy blue pants wanders onstage. I think the electrician has finally arrived to fix the lights. But it is Galliano himself, the hottest ticket in town. The audience roars its approval. Le tout Paris is paying its respects. And the man isn't even French. Worse, he's a Brit.

Nor is he a lone invader. Paris remains the epicenter of international fashion. But the French no longer call the shots. Last fall's pret-a-porter collections for this spring and summer marked the first time ever that French designers were outnumbered by foreigners.

"Paris is still the capital of concepts," says Philippe Starck. "The level of sophistication here is unmatched anywhere else in the world." Maybe. But it is no longer as obvious as it was that the chicest females in the world want to look like Frenchwomen, and if you scratch many a famous French fashion label these days you're likely to discover a foreign name.

Chanel has a German (Karl Lagerfeld), Lanvin a Brazilian-Italian (Ossimar Versolato), Dior an Italian (Gianfranco Ferre), and an American (Oscar de la Renta) is at the helm at Balmain. There is an Irishman at Rochas, a Dutchman at Balenciaga, and a German at Nina Ricci.

The French fear that the decline in the supremacy of French fashion is a symbol of a far wider malaise in Parisian social and cultural life. Behind its impressive, immaculate facades, rigor mortis has set in. No great painter has emerged since Matisse died in 1954. The famous philosophes are silent. "Intellectual debate is missing," says Ockrent.

"I feel a sense of decline," says Starck. "The energy is draining, a negative atmosphere is growing." The worry is that France is past its best, its fabled quality of life increasingly unaffordable, its civilized ways under threat from foreign barbarians.

Gallery owners complain about sagging sales, dealers about how the market for even French-owned works of art has moved to New York and London. "There are no decent prices to be had in Paris," explains Princess Laure de Beauvau-Craon, the head of Sotheby's French operations. "But the French need money, so they ship their works to New York, where sales are booming. Our turnover is up 40 percent because of that. But the market is dying here."

In last fall's pret-a-porter colections, French designers were outnumbered by foreigners for the first time.

French cuisine is stuck in a time warp: red meats, heavy sauces, million-calorie desserts are still the order of the day. The healthier eating inspired by American cuisine over the last two decades has made little impact in France.

Despite the huge subsidies and state support for the French cinema, it is moribund, its stars seeking work in Hollywood because, like French audiences, they prefer the international appeal of American Films. "French films follow a basic formula," complains Sophie Marceau, one of France's most popular actresses, who played the Princess of Wales in Mel Gibson's

Braveheart. "Husband sleeps with Jeanne because Bernadette cuckolded him by sleeping with Christophe—and in the end they all go off to a restaurant. How many times can you act in that kind of film?" She is working in Hollywood, says this woman regularly voted the epitome of French womanhood, because "the French cinema is in a deplorable state."

greatest wish is that when my son and daughter grow up, they will become civil servants," wrote a mother to Le Figaro magazine recently. If Americans dream of getting rich, the French aspire to power and prestige. To become a civil servant sets you up for life. At worst you will enjoy secure employment, early retirement, and a handsome pension; at best you will run one of the great departments of state, or a great public enterprise—or even become president.

Entrepreneur is a French word, but there are precious few French entrepreneurs driving the economy. This is a country in which big is beautiful and big government thought to be most lovely of all. Roughly 25 percent of the workforce is employed in the public sector, compared with 14 percent in America. The French love government so much that they added more than 370,000 civil servants in the past decade.

The origins of a large and active state can be traced back to the 17th century, when Jean-Baptiste Colbert centralized power in the hands of his monarch, Louis XIV. It was enhanced by Napoleon and continued to grow after the Second World War under the dirigiste policies of left and right. Today the state spends 55 percent of France's G.D.P.— the largest share among the world's major economies—and the French have become one of the most highly taxed people in the world to pay for it.

They expect a lot in return. But the state can no longer provide all it is meant to deliver. It cannot create jobs for everyone, cater to every welfare need, keep the franc strong and taxes low, and spread its wings even further. It is already a leviathan stifling economic energy and cultural creativity. Something has to give. What and how will determine not just the future of France but also that of the European Union.

France has become Eu• rope's swing state. If Chirac * ^ and Juppe can keep the show on the road with only minor adjustments, then France will join Germany in an ever closer European Union. If it blows apart under the weight of its internal contradictions, then the sort of European Union envisaged by the Maastricht Treaty and encouraged by successive administrations in Washington is dead for perhaps a generation, and France will have entered uncharted waters.

As Christmas approached, the beleaguered Juppe showed signs of caving in, scaling back essential reforms for the public-sector pension system and money-losing state railway authority. Public-transport workers ended their three-week strike, but union leaders warned of further disruptions in the months ahead.

Will major change come with violence? "Always," says Starck without hesitation. "People don't believe in politics anymore. We're seeing the quiet before the storm."

The French have always needed a father figure, be it Napoleon or Mitterrand. Under Chirac, France is an orphan, and is once again up for adoption. But not even the French know whose tender mercies they will next embrace when they Finally emerge from this winter of discontent.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now