Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowEditor's Letter

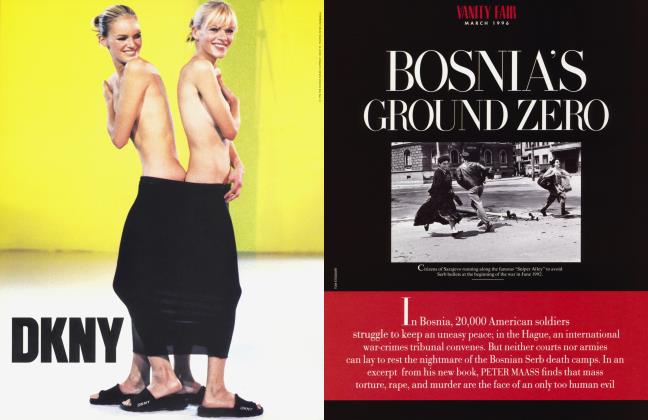

Bosnian Nightmare

The staggering dimensions of the tragedy in the Balkans have preoccupied Americans on and off for five years now, in a kaleidoscopic progression: the breakup of Yugoslavia, the Serb campaign to occupy and "cleanse" large parts

■ of Croatia and then Bosnia, the siege of Sarajevo, reports of rapes and massacres by Serb militias, an imperfect peace process that culminated in the Dayton agreement and the Christmas 1995 mobilization of U.S. troops and their halting deployment this year.

For reporters on the ground, like Peter Maass, who covered the conflict in Bosnia for two years for The Washington Post, the horror of what they saw was compounded by the constraints of daily journalism. "It nagged me that all these 800-word and 1,200-word stories were pieces of a puzzle that hadn't been put together," he says. And so he wrote a book, Love Thy Neighbor: A Story of War, to be published this month by Alfred A. Knopf and excerpted on page 145. Maass has produced a passionate and compelling account of the war, fueled by his anger over what happened in Bosnia—the mass murder, mass rape, and torture of the Serb "cleansing" campaign, and the West's acquiescence in the dismembering of a country.

In trying to come to terms with the Bosnian nightmare, Maass was reminded "that societies are much more fragile than

we think. There's this kind of inborn conceit we have that it couldn't happen here, because we're Western, American, the su9 perpower. We've become accustomed to such a level of violence in our country without thinking it's a sign of vulnerability." His description of the Serb-run death camps, in fact, derives much of its brute power from his awareness that the atrocities were taking place in what had been, only a few years earlier, a sophisticated European society. As he writes about his visit to one of the concentration-camp commanders, "What I find most remarkable about the session is that I cannot recall the chief investigator's face. It is a total blank, gone from my memory or sealed in a corner I cannot reach, no matter how long and hard I think. ... It is as though my subconscious were playing a trick on me, perhaps trying to send me a message that the man's identity is not important: he is just another human being, faceless. He is you, he is my friend, he is me."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now