Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLOVER GIRLS

With the superpublicized coming-out of sitcom star Ellen DeGeneres, lesbian chic has gone utterly mainstream. But who made gay women into the media culture's sexiest new properties? Straight white men

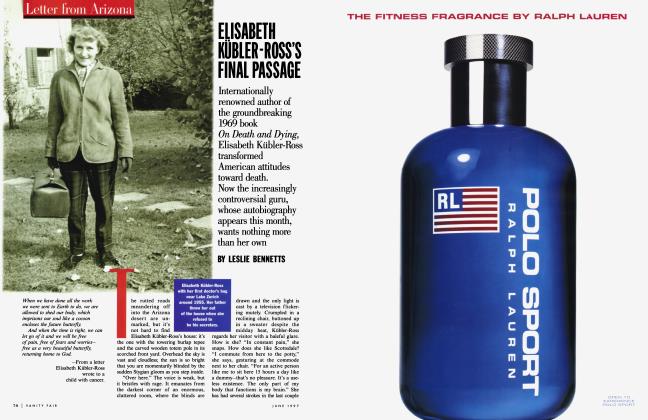

James Wolcott

A funny thing didn't happen on a recent edition of CNN's Crossfire (March 11, to be exact). The topic was federal funding of the National Endowment for the Arts, which had come under fresh bombardment from Republican congressman Pete Hoekstra, among others, who complained that taxpayer money was once again subsidizing smut. As a bearded and darkly clad Alec Baldwin, impressive and smoothly menacing in his new role as arts advocate, laid out a cogent defense of the N.E.A., hothead Crossfire co-host Pat Buchanan badgered away like Senator Joe McCarthy defending the sanctity of the American cave, demagoguing against some dinky documentary "about 12-year-old lesbian girls coming out"— which he called "child pornography," as if that would give everyone shudders. It didn't. Thrown off stride, Buchanan became flustered, hapless; his rhetorical punches turned puffy. Finally, in a lastditch effort to scare up some controversy, he latched onto another N.E.A. fundee, a film called The Watermelon Woman— 'It was about black lesbians," he barked. But again no one fainted. His mock outrage seemed quaint. Not for the first time, Pat Buchanan had misjudged the Mood of the American People. Although prejudice still exists, public ostracism is out. America has found a place at the table for the lesbian, adopted her as a comic sidekick and buddy. This development may dismay some hard-core gay activists as much as it dismays conservatives like Buchanan, but there's no returning to the old melodrama.

Even before Ellen DeGeneres began poking her head out of the closet and playing peekaboo, the media fascination with lesbians had reached nova stage. Where once the mere malicious mention of lesbianism could be life-ruining (see Lillian Heilman's play The Children 's Hour), now the word has acquired designer-label panache. In the 70s, "lesbian" was still a fighting word, a stigmatizer, used against feminists as a putdown (buncha dykes), then picked up and brandished by some militant feminists themselves as a proud and defiant up-yours. The word and everything it signified did prove to be a wedge. "Maleidentified" women still had to fuss over matters like how to dress nice for the office and their feelings for Stan and the kids. Forget Stan and the kids! Only lesbians, unencumbered by such petit bourgeois baggage, could be clean bullets for the feminist cause. They alone were in touch with their true nature. "All women are lesbians except those who don't know it," Jill Johnston wrote in her 1973 manifesto, Lesbian Nation, a book she dedicated to her mother ("who should've been a lesbian") and daughter ("in hopes she will be"). "Until all women are lesbians there will be no true political revolution," Johnston exhorted in italics. It was a message she carried to the stage of New York's Town Hall for the famous debate on feminism (primarily) between Norman Mailer and Germaine Greer, where Johnston giddily rolled on the floor with her girlfriends until Mailer, acting as M.C., snapped, "Come on, Jill, be a lady!" More futile words have seldom been uttered.

Instead of a triumphant worldwide upsurge, the lesbian movement, like so many liberation movements of the 70s, flaked off into grumbling factions and separatist communes. To some interested parties, this opting-out was a big step back. "Now that 25 years have passed, it's time to admit that lesbian feminism has produced only the ghettoization and miniaturization of women," Camille Paglia wrote in her slashing 1994 essay "No Law in the Arena" (Vamps & Tramps). Cutting themselves off from men hadn't made lesbians stronger, Paglia argued, but more co-dependent. "In such a situation, men are divided from themselves, and women simply fail to mature."

After the AIDS devastation of the 80s, which left gay women eclipsed in the deadly shade of gay men in the public mind, lesbianism surfaced as a sexy topic, due in no small part to ideological swashbucklers like Paglia, along with "sex-positive" postfeminist prose exhibitionists like Susie Bright and Lisa Palac. No longer was the stereotype lesbian an R. Crumb earth mama in overalls and work boots worshiping the Goddess within, the erotic equivalent to a Russian tractor. No, the new stereotype lesbian was a girlie girl and go-go dancer. The steamy lambada between Sharon Stone and Leilani Sarelle in Basic Instinct set the tone. The 90s have seen a cascade of articles on "lesbian chic," a lifestyle trend incorporating everything from Melissa Etheridge and her lover celebrating lesbian motherhood on the cover of Newsweek to the popularity of writers like Jeanette Winterson (who shocked and amused the literary world earlier this year when she claimed she had worked as a lesbian prostitute in London hotels—where she was paid for her services in saucepans) and Dorothy Allison (who posed for The New York Times Magazine in biker gear); from the date-night following for Go Fish (which turned the lobby of the Angelika Film Center into a cruising spot) to the torrid female wrestling of Bound. Xena: Warrior Princess, a popcorn machine for male hormones, has become a role model for teenage females and a huge lesbian cult hit as well, Xena's studded outfits being the last word in feudal bondage actionwear. Finally, a dominatrix the whole family can enjoy . . .

'Now the word lesbian has acquired designer-label panache.'

Not surprisingly, this flashy coverage has created corrugated brows among the punditry. For this is America, nation of worriers. "What concerns me is that the media will make lesbian chicness all about bell-bottoms and pierced body parts, and not about safeguarding basic rights," Wendy Wasserstein wrote in Harper's Bazaar, a sentiment echoed by Kara Swisher in The Washington Post: "Even with the welcome warmth of the spotlight, lesbians shouldn't allow anyone to exploit them for their trendiness. If they do, they will inevitably be left behind on the fringes of cultural acceptance with new and damaging stereotypes to counter." What perturbs such commentators is the fact that lesbians are being exploited as hot properties by the traditional custodians and peddlers of pop culture—straight white men. Anything that gets them going can't be good.

Macho men have often expressed an affinity for lesbians. They can relate to them as rugged equals—tomboys who didn't turn soft. The director Sam Peckinpah called himself "one of the foremost male lesbians"; Ernest Hemingway, a frequenter of Gertrude Stein's salon in Paris, used his attraction to lesbians to explore androgyny and homoerotic transfiguration in his fiction, most notably The Garden of Eden (the shorthaired girl serving as a substitute boy). The tenor of American pop culture is no longer set by such hairy-chested hardies but by weedier guys who might be called inverse-machos. They try to dominate women through whining. To lechy boy-men like Howard Stern or A1 Bundy on Married ... with Children, the kind who brag about how bad they are in bed, lesbians have acquired a kick-ass babe-osity. Not only can they sexually reject you but they can beat you up too, which some men find a thrilling combination. "Lesbians mean ratings," Stern has often said ("The Lesbian Dating Game" certainly boosted his), but the dumb wonder that glazes his face and clouds his glasses when your average silicone-enhanced, snake-tattooed, bodypierced lesbian stripper flops down in his studio speaks of more than Arbitron numbers. On El's Night Stand, a satire of trash TV, the host, Dick Dietrick (Timothy Stack), is likewise obsessed with lesbians, conducting a quiz on the subject "So You Think You're a Lesbian." What unites Howard Stern and Night Stand is a porn mentality linked to a slapstick ineffectuality. Good-looking lesbians are making out better with women than they are. If women don't want them, couldn't they at least hang around and watch? You know, pick up a few pointers.

Fox's "Married With Children" is joining the lesbian contingent . . . two days before ABC's "Ellen" airs its controversial "coming out" episode.

On the "Married" episode . . . titled "Lez Be Friends"—A1 (Ed O'Neill) makes friends with next-door-neighbor Marcy's identical cousin, Mandy—only to learn Mandy is a lesbian. . . . Amanda Bearse— who plays both Marcy and Mandy—is an open lesbian.

—New York Post, March 28, 1997.

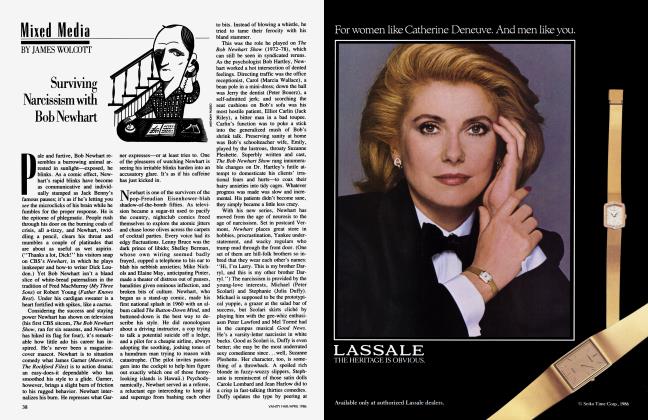

The feeding frenzy over which way a fictional character and his or her real-life counterpart swing is a fairly recent phenomenon. TV fans always suspected that Miss Hathaway on The Beverly Hillbillies wasn't saving herself for Jethro, and that Sheena, Queen of the Jungle—a precursor to Xena—was a trifle butch, even for an Amazon. With the exception of Maverick, the Warner Bros. Westerns of the late 50s and early 60s—The Lawman, Sugarfoot, Cheyenne, Bronco—were a fantasy dude ranch for gay wranglers, something sensed at the time but left unsaid. A trace of ambiguity gave the characters crossover appeal to the mass audience and a coded message to Camp followers. (The Chuck Connors series Branded was a gay allegory about public shaming, the show's theme song asking, "What do you do when you're branded? / And you know you're a man.") As gay pride came to the fore, there was less need and willingess to "pass," and uncloseted characters began to circulate. The yuppie gay man, with his droll quips and primpy fashion sense, became a sitcom fixture. Lesbians are less sharply defined and contained, more open to suggestion. (Even certified losers like Seinfeld s George Costanza and Rob Schneider's character on Men Behaving Badly think they have a shot with them.)

Take Roseanne, an invaluable flowchart for the Zeitgeist, even in its jagged decline. Its gay male couple, played by Martin Mull and Fred Willard, couldn't be more minty and cuddlesome. They're so selfconsciously retro that it becomes a protective coating of irony. Flinging themselves giddily into the enjoyments of middle-aged gay men (encyclopedic knowledge of Broadway musicals, etc.), they emerge as perpetual-adolescent elves, like the birdbrains in T!\e Birdcage. It's impossible to imagine Mull's and Willard's characters involved with women, they've built themselves such a private nest. In contrast, Sandra Bernhard's lesbian character is moodier, slouchier, sometimes sauntering into sex with men; her body language is pure laissez-faire.

This season, however, Roseanne betrayed a heavier hand. In the Thanksgiving episode, Roseanne's mother (Estelle Parsons) blatted out above the holiday family din that she was gay—a bombshell that was painful to watch and worse to hear, not only because it wasn't funny but also because it seemed so forced and unnecessary. You felt the punch-drunk old bat was being dragged out of the closet. The show's former live-and-let-live attitude had soured and deteriorated into in-your-face confrontation. But if the episode failed as comedy (every Roseanne episode this season has failed as comedy), it succeeded as a demonstration of the doctrinaire pressures placed on fictional characters and the actors portraying them to declare themselves. How appropriate, then, that Ellen Morgan would come out on Ellen by yelling "I'm gay!" over a loudspeaker. It's as if nothing can be said at less than top volume now. Words have no weight unless they're amplified.

'The director Sam Peckinpah called himself "one of the foremost male lesbians.'

We live in an era of full disclosure, which allows for greater frankness and freedom, and stronger rips of satire. But it's also a period which distrusts and devalues mystery, artifice, understatement, insinuation. Our pop culture wants everything and everyone nailed down, neatly labeled, explicit. The intellectual practitioners of postmodernism may preach a porous unisexuality in which male and female commingle and share each other's wardrobe (the body as Web site), but the tabloid press, which is the dominant influence on media culture today, works from a moralistic takedown mentality. Its job is to squeeze out confessions or, failing that, get the goods. Hence the off-guard grainy "Gotcha!" shots of a female celebrity with her "gal pal" which turn up in the tabloids almost every week. The tabloid foragers assume that each celebrity has a private and public face, like two sides of a trading card, and that when the two sides clash, it's open season. Some of the celebrities who come out may do so less from pride than from battle fatigue. They're tired of being dogged.

Of course, no one should stay in who wants to be out, whatever the reason. In the case of DeGeneres, her strained discomfort and overcompensation in playing a straight romantic lead in the movie Mr. Wrong was snickeringly noted by reviewers. She didn't receive the mortifying ridicule Lily Tomlin and John Travolta did for Moment by Moment (critics cracked up when Tomlin made heavy-lidded love eyes at Travolta in the hot tub), but the critical and commercial flop of Mr. Wrong may have convinced her that no one was going to buy her as a straight romantic lead anyway, so why bother? At least on her own show she could drop the pretense. "Yep, I'm gay," she told Time magazine.

The irony is that the superpublicized outing episode of Ellen may end up representing the final peak of lesbian chic. This pseudo-event comes at a time when the condition and definition of being a lesbian are undergoing so much scrutiny and erosion. The fun seems to be fading. In 1994, Sandra Bernhard, former Madonna playmate, told Kevin Sessums in Out magazine, "I don't care to define myself as a lesbian. I hate that fucking word. It's a nasty, dirty, fucked-up word. It's not a glamorous word. It's not a sexy word. It's dry. It's colorless." Two years later, k. d. lang told Out, "I feel like all the lesbians are starting to fuck men. All the straight girls want to be lesbians. I'm feeling very alone." As if to re-establish a beachhead, hypercerebral poststructuralist rallying statements like Sue-Ellen Case's The Domain-Matrix: Performing Lesbian at the End of Print Culture are attempting to do for the wired 90s what Lesbian Nation did for the heady 70s—demarcate gender lines and boost troop morale. That may be the mission for lesbian feminists in the 21st century; retaking lesbianism from all the wannabes, backsliders, and male gawkers. Good luck, gals!

In the meantime: if Pat Buchanan really wants to study lesbian style in action, he ought to check out the performance of his own sister Bay on CNBC's Equal Time, a hatchet woman with a tough hide who's living proof of Camille Paglia's adage "The real hutches are straight."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now