Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWHITE HOUSE AT WAR

When Bill Clinton finally confessed to sexual contact with Monica Lewinsky, his vaunted White House spin machine blew a fuse. Betrayed and confused, Clinton's closest aides struggled with the president's rage, conflicting leaks about Hillary, rumors of a Second Intern story, and the looming avalanche of the Starr report

HOWARD KURTZ

Letter from Washington

It was a day of roiling emotions at the White House, a combustible mixture of anger, depression, and stomachchurning uncertainty. For seven long r months, the president's closest aides had been telling reporters and the country that Bill Clinton had not I had sexual relations with "that woman," putting their own cherished reputations on the line. And now, on the afternoon of August 17, 1998, the stone wall had collapsed. The president was in the historic Map Room, telling Kenneth Starr and his grand jury that he had indeed had sex with Monica Lewinsky—that in essence he had wagged his finger at the country and lied, that he had lied as well to White House spokesman Mike McCurry and top aides Paul Begala, Rahm Emanuel, Ann Lewis, and Joe Lockhart, and encouraged them to lie on his behalf.

They were the key players in the vaunted Clinton spin machine, a round-the-clock operation with a dizzying ability to beat back scandalous headlines, attack the accusers, change the subject, bully the press, and keep the president's all-important poll numbers at gravity-defying levels. The masters of spin would alternately castigate and coddle reporters, stage events for television, leak good news about the president (and leak bad news in order to soften the blow), blitz the morning talk shows, and generally work the press in every conceivable fashion. They had raised the art of media manipulation to unprecedented heights.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 37

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 32

Every administration tries to cast its leader in the most favorable light. But spin had become a survival strategy in the Clinton White House—a way to get through the treacherous Whitewater mess, the seedy spectacle of Johnny Chung and Charlie Trie steering funny money into Democratic campaign coffers, the lurid pants-dropping accusations of Paula Jones. Each time the increasingly hostile journalists felt they finally had Clinton cornered, the president would somehow manage to escape.

But now the spin machine had sputtered to a halt. McCurry, Begala, and the rest knew that political spin could be successful only as long as it was tethered to reality.

They would not insult reporters by making some sort of robotic argument that minimized the humiliation of the moment and the grave threat to Clinton's presidency. In an administration in which virtually every move was scripted, every photo op carefully staged, every presidential answer to a reporter's question rehearsed in advance, there was, for the moment, no real game plan.

And yet the urge to gloss over the unvarnished truth was so deeply ingrained among the Clintonites that staff members were handed a set of "talking points" for the occasion. The three-page memo, written by White House scandal spokesman Jim Kennedy, was meant to prepare Emanuel and Lewis for their network appearances the next morning. But it was distributed throughout the West Wing, guiding officials on what to say if reporters asked about their personal reaction to the president's deception.

Sample question: "Do you forgive him for misleading you and the country?"

Suggested answer: "It's been said that he who cannot forgive others breaks the bridge over which he must pass himself. Of course I do."

McCurry couldn't believe the stupidity of the memo; he didn't know whether to laugh or cry. Lockhart crushed the paper and tossed it into the trash can. No one was going to tell him what to say about his own feelings. His advice was simple: Say whatever you want. If it hurts the president, don't say it. If it's that bad, quit. And that was an option that could not easily be dismissed.

Ever since the third weekend in January, when Clinton learned that "The Sludge Report," as he called Matt Drudge's gossipy Web site, had run an item on his illicit relationship with Lewinsky, the inexorable tension between the cover-up of a sexual affair and an increasingly tabloid media had been building toward this day. The reporters had squeezed out the evidence in dribs and drabs—the frequent Lewinsky visits, the tacky gifts from Clinton, the Secret Service suspicions, the famously stained Gap dress—but the president who had promised "more rather than less, sooner rather than later" kept brushing aside their questions. Clinton's approval rating remained over 60 percent, and he was convinced that ordinary Americans cared far less about his private life than did the inside-the-Beltway media elitists who had long viewed him as a slippery rube from a backwater state.

The animosity between the president and the press had never been more palpable. Many of the journalists who had covered Clinton since the I-didn't-inhale days of the '92 campaign had since learned to parse his every word. They had seen him wiggle his way out of controversies involving Gennifer Flowers, the forgotten draft notice, Travelgate, Filegate, and a host of lesser Gates, and they were frustrated by their inability to hold him accountable, to make the public share their outrage at his lack of candor. They had derided his second-term issues, from cutting school-class sizes to a patients' bill of rights, as small change, but Clinton had a way of connecting with the public over these back-fence concerns. Each day, each hour, had evolved into a clash of alien cultures—a White House determined to break through the media static and a press corps seemingly obsessed with the latest scandalous allegations.

To the press, the Lewinsky story wasn't just about sex—although sex was certainly boosting the ratings of the cable shows that feasted on the salacious details night after night. It was also about Ken Starr's investigation of perjury, subornation of perjury, and obstruction of justice. When the ⅝ public finally grasped the larger picture, the journalists believed, Clinton would surely be run out of town. And so, from the claustrophobic confines of the dingy White House pressroom, they clamored for answers.

Each time journalists felt they had Bill Clinton cornered, the president would somehow escape.

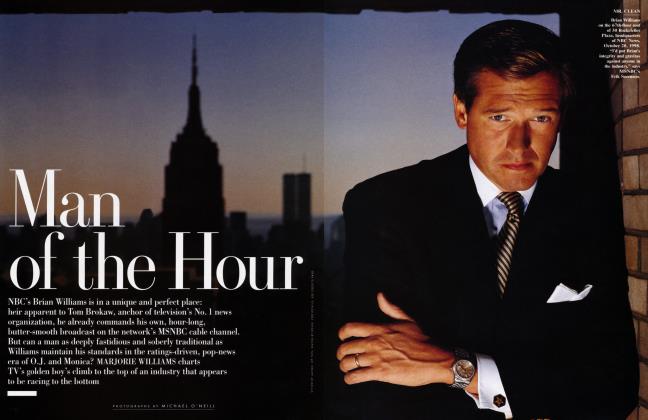

Mike McCurry bore the brunt of their frustration. A Princeton graduate who had cut his teeth on Capitol Hill and at the State Department, he was the public face of the spin machine, the witty but increasingly testy press secretary who got pounded each day by the likes of ABC's Sam Donaldson, NBC's David Bloom, and CNN's Wolf Blitzer. McCurry had been the man on the podium for nearly four years now, and he knew how to bob and weave and dance out of danger.

On the Lewinsky story, however, he was curiously disengaged. McCurry could not field the questions and, fearing a Starr subpoena, did not want to know the answers. He proudly proclaimed himself to be "out of the loop." He was "doubleparked in a no-comment zone." He noted that he was simply repeating the meager bits of information given him by David Kendall, the president's private attorney, and Charles Ruff, the White House counsel.

McCurry had announced that he would be leaving the White House in early October. He had long planned to bail out sometime in 1998, and had been worn down by the endless Lewinsky inquisition. He knew he was becoming the butt of jokes, a human synonym for stonewalling, and it gnawed at him. McCurry became even more detached as the workload shifted to his hard-charging deputy, Joe Lockhart, who would succeed him in the daily televised warfare.

By the last day of July, as the usual summertime haze settled over the capital, it had become obvious to everyone that Clinton would have to admit to some kind of sexual contact with Lewinsky, especially now that she had turned over the semenstained navy-blue dress. The former intern had finally struck an immunity deal with the independent counsel, who in turn had subpoenaed the president—although McCurry infuriated reporters by refusing to confirm the subpoena until well after the news had leaked out. Now that Clinton had agreed to testify, the question was whether he would change the story he had told seven months earlier in his deposition in the Paula Jones sexual-harassment suit, when he denied having had sexual relations with Lewinsky. "I've never had an affair with her," Clinton had testified. The pundits and the politicians were pressing for what came to be called "the mea-culpa scenario," in which Clinton would confess wrongdoing and ask the country's forgiveness; everyone, it was said, would be ready to move on.

While Clinton was announcing some second-quarter growth figures in the Rose Garden, the reporters were herded behind a distant rope line. In a scripted finale, the president said that he planned to testify fully and truthfully to the grand jury, then abruptly turned and walked back toward the White House. Sam Donaldson's voice could be heard above the din of shouted questions, asking if Clinton would provide prosecutors with a DNA sample. Two weeks later, the high-decibel ABC correspondent was still trying to pin down McCurry at the afternoon briefing.

"The president said that he would testify truthfully and fully next Monday. Does 'fully' mean that he intends to answer all the questions put to him?"

"Sam ... the president addressed these matters and made it clear he wasn't going to have anything more to say on it until he testifies on Monday.... I'm not going to play that game."

These are legitimate questions, Donaldson said.

"I don't have anything to add," McCurry snapped a moment later.

"Why can't you say he'll testify fully.... Why would you try to be cute about that?"

"You played this same semantic game with Mr. Lockhart yesterday. . . ."

"This is not a semantic game. . . ."

"I'm not playing this game today."

McCurry felt he should not have held a briefing right after returning from vacation. He had let Donaldson get under his skin, had looked peevish and defensive. The reporters in the briefing room always taunted him, hoping he would lose his cool and make some news. Today he had played into their hands.

The White House political advisers favored the contrition route, but they had long since lost control of the case to the president's legal team. The lawyers, concerned more with criminal liability than with political strategy, held each scrap of information closely, and generally would allow no public comment. McCurry and Lockhart were stymied. They couldn't provide any guidance to reporters, even off the record, because they were being kept in the dark. Lockhart wouldn't have trusted any guidance about Clinton's upcoming testimony, because it wasn't clear who really knew what was happening.

The next morning, Friday, August 14, the debate spilled onto the front page of The New York Times. Clinton's senior advisers had decided to use the press to send the boss a message: It was time to come clean about Lewinsky. The story said the president had had "extensive discussions with his inner circle" about acknowledging "intimate sexual encounters" with the smitten young woman from Beverly Hills. But no one on the political staff was sure of Clinton's final decision.

"What's he going to say he did?" McCurry asked John Podesta, a deputy chief of staff.

"I don't have a clue," Podesta replied. McCurry warned Kendall that they had to be careful about a public defense that would seem to be parsing the definition of sex. The press secretary had long believed that Clinton probably engaged in heavy petting with Lewinsky but had stopped short of full-fledged sex. But if the president was about to acknowledge some kind of sexual activity with Lewinsky, there were going to be a lot of hurt and confused people in the White House. Clinton had looked them in the eye and told them he did not have sex with Lewinsky. McCurry sent word to the president that he should not forget about making things right with those who had loyally defended him. The president's conduct, he felt, had been exasperatingly stupid.

By Sunday, Washington Post investigator Bob Woodward was quoting a person who had spoken with the president as saying that Clinton's lawyers believed he would change his story and could acknowledge engaging in "sex play" with Lewinsky. The problem, it seemed, was that the president had not warned Hillary or Chelsea of the trauma to come. "He has not prepared the family," an unnamed source said ominously. Woodward had long been friendly with Chuck Ruff, the wheelchair-bound former Watergate prosecutor, and Woodward's byline always carried an extra bit of authority. Clinton was annoyed at these accounts, which made it appear he was choosing among different versions of the truth, but the White House did not deny them.

Even in off-the-record conversations about the president, Paul Begala would lower his voice and say, "I believe him."

As Clinton and Starr took their seats in the Map Room the following afternoon, CNN was driving Lockhart crazy by running a small "game clock" on the top of the screen, ticking off the elapsed minutes. Lockhart twice called CNN correspondent John King to complain that the clock wasn't accurate, since the two sides were taking unspecified breaks. CNN killed the clock, a small if meaningless victory for the administration.

At 10 P.M., Clinton was back in the Map Room, confessing to the country that his relationship with Lewinsky was "not appropriate.... I misled people, including even my wife." But the expression of regret seemed perfunctory, giving way to a passionate assault on Ken Starr for "prying into private lives." The staff was horrified. And the pundits, that omnipresent Greek chorus that seemed to hector the president at every turn, were trashing the speech within minutes.

"He didn't come clean tonight with the country," declared Sam Donaldson.

"This was Slick Willie in operation," said Fox's Morton Kondracke.

"I'm not sure he's come to terms yet with how much he has soiled his own presidency," said Newsweek's Jonathan Alter.

The speech was such a disaster that the usually disciplined strategists began furiously leaking, in an effort to distance themselves from the mess. The address had been drafted by Paul Begala, a redbearded Texan with a fondness for profane talk and cowboy boots. Begala was among the most evangelical of Clinton's loyalists—even in off-the-record conversations with reporters, he would lower his voice and whisper, "I believe him"—and was particularly crushed by the admission of lying. Begala's first draft contained a stronger apology and no attack on Starr. Kendall wanted a limited apology that would not increase the president's legal liability. Sidney Blumenthal, a former journalist who viewed Starr as part of a conservative cabal, pushed for blunt criticism of the prosecutor, faxing in his suggestions from a European vacation.

Hours before the speech, Mickey Kantor, Clinton's friend and legal adviser, gave Begala the president's handwritten notes, which included the harsh language against Starr. Begala took it out of his next draft, but in a meeting in the White House solarium an hour before airtime, the political aides saw that Clinton had put the attack back in. As the wrangling continued, Hillary told her husband that it was his speech and he should say what he wanted.

The next morning, the First Lady's advisers debated whether she should make her own statement. They were worried that she was an emotional wreck, but they also needed to know the truth: Had she really believed that Bill was "ministering" to a troubled young person, as she had told Sid Blumenthal? Once they were persuaded that Hillary had actually been kept in the dark, they urged her to go public to preserve her credibility. After all, she had dismissed the allegations on the Today show as the product of a "vast right-wing conspiracy."

Hillary phoned Marsha Berry, her spokeswoman, and told her to put out the word that the president had deceived her. Berry called 100 reporters to say that her boss had been "misled." White House officials openly scoffed at this notion, telling reporters that Hillary must have known of the affair. Hillary was angry at these leaks, which seemed to compound her misery by painting her as a liar. It was an extraordinary spectacle, a president and First Lady peddling competing accounts of her awareness that he was cheating on her.

When the Clintons and their daughter retreated to Martha's Vineyard the day after the speech, McCurry and others told reporters that things were tense and that the president was in the doghouse. The spin, it seemed, was that Clinton was being duly punished on the home front. But Newsweeks editor-at-large, Kenneth Auchincloss, on vacation near the presidential compound, saw the couple locked in a long embrace as they wandered onto his private beach. He notified Newsweek executives, but they decided the incident was ambiguous and didn't fit into their coverage.

"I'm not playing this game today," snapped Mike McCurry after Sam Donaldson confronted him at a press conference.

A variety of polls showed that 6 in 10 Americans believed the president's apology had been sufficient, but the reporters and commentators continued to hammer him.

Joe Lockhart thought the sharks were in the water. Lockhart, who had been the spokesman for Clinton's 1996 campaign, understood the media mentality better than anyone at the White House, having been a producer and assignment editor for three networks. The press pack, he believed, wanted Clinton to grovel. The talking heads spent hour after hour prescribing the proper degree of humility, yet whatever Clinton said they started picking it apart 15 seconds later. They wanted him to apologize to every MSNBC pundit and CNN analyst who had used the Lewinsky story as their ticket to media stardom. It was absurd; no amount of contrition would be enough for that crowd.

The master of compartmentalization was in the Kremlin, trying to leave the Lewinsky mess behind. It was September 2, and Clinton had spent two days dealing with Russia's economic collapse. Now he was preparing for a joint news conference with Boris Yeltsin.

The Clintonites had been through this drill before. They knew that a minor matter like the political and economic disintegration of a nuclear power would not distract reporters from their Lewinsky obsession.

When Clinton had been in Europe to sign an agreement aimed at expanding the NATO alliance into Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic, the reporters asked about Paula Jones. When Clinton had been in Mexico meeting with President Ernesto Zedillo, they asked about Whitewater. When Clinton had been meeting with Chilean president Eduardo Frei, they asked about campaign-finance abuses.

In the final minutes of an hour-long prep session, McCurry, Lockhart, and Doug Sosnik, the White House counselor, told the president that most of the American reporters' questions would be about Lewinsky.

"Really?" Clinton said, sounding surprised. He had convinced himself that the press would focus on the Russian economy.

The president seemed drawn and downcast as he sat with the ailing Yeltsin. But when Larry McQuillan of Reuters asked about the adequacy of his August 17 speech, Clinton engaged in a bit of revisionist history so audacious that the reporters could only shake their heads in wonder. "I thought it was clear that I was expressing my profound regret to all who were hurt.... I have acknowledged that I made a mistake, said that I regretted it, asked to be forgiven." Clinton had never asked to be forgiven or apologized to those who were hurt, especially Lewinsky, but now he simply decreed that he had.

As the media continued to demand a more abject apology, Clinton's staff tried to persuade him that even his Democratic allies on Capitol Hill felt he needed to say more. The drumbeat had become deafening, they told him; he couldn't just return to business as usual.

But first, his closest aides came to realize, Clinton had to let go of his anger. He had raged about Ken Starr for four years now, and was equally enraged at journalists for seeming to gobble up Starr's improper leaks without holding him accountable for prosecutorial abuses. The president would rant and rave about this. One reason the spin team always conducted a "pre-brief"—a formal session in which Clinton practiced his answers before venturing within earshot of reporters—was to give him a chance to vent in private.

As McCurry, Lockhart, Begala, and the rest urged Clinton to make a more complete apology, they saw that he was just starting to internalize the grief he had caused those around him. He could not have delivered a more heartfelt apology on the 17th, because he wasn't there yet. As Clinton finally came to grasp the utter inadequacy of his earlier comments, a consensus emerged that he should try again at an upcoming White House prayer breakfast. Clinton began drafting his remarks in Europe and, in a startling move, did not review them with the staff. His aides realized that he had to work this out on his own. "I don't think there is a fancy way to say that I have sinned," Clinton told the assembled religious leaders, his voice choked with emotion. By now, though, the punditocracy that had demanded greater contrition was ridiculing Clinton's apology tour.

The press had turned on the president with a vengeance. More than 140 newspapers— The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Des Moines Register, The Seattle Times, even the administration's favorite paper, USA Today— were urging him to resign. The Clintonbashing columnists were in full cry; Michael Kelly of the National Journal dismissed the president as "a pig and a cad and a selfish brute." Even reliably liberal columnists who had defended Clinton—Clarence Page of the Chicago Tribune and Lars-Erik Nelson of the New York Daily Nevus'—insisted it was time for the "moral pygmy," as Nelson called him, to pack his bags.

The news coverage, filled with dark talk of impeachment, was as overheated as ever. Even one of McCurry's favorite journalists, a fair-minded, bearded CBS producer named Mark Knoller, seemed disillusioned. When Knoller mentioned that he would never look at Clinton the same way again, the White House team was shaken. If they lost Knoller, McCurry thought, they had lost the press corps.

McCurry felt as if they were in a sailboat being buffeted by a raging hurricane. But he couldn't complain about the reporting; all the sexual allegations he had thought were unfair when they had been published months earlier had turned out to be true. The reporters, McCurry believed, felt that Clinton had lied to them personally. They had been in the Roosevelt Room back in January when the president had made his impassioned denial, and he had wagged his finger at them. Whatever he said on any subject was now automatically discounted. "The White House lies about everything; our credibility is zero," McCurry said sarcastically. That was the price they were paying for the president's cover-up.

Away from the spotlight, in hundreds of whispered conversations, both the White House and the press had become consumed by the Second Intern story. Rumors swept the city that some reporter, usually Bob Woodward, was about to disclose that Clinton had had sex with another White House intern and, in some retellings, a third or even a half-dozen. This, everyone agreed, would finish him off. Rahm Emanuel became so frustrated that he called a Washington Post editor to find out whether such a story was imminent. It wasn't, but that did nothing to quell the storm.

Chuck Ruff, who knew that Woodward always visited a family retreat in rural Michigan in late August, tried to calm the staff. "I don't know how he's breaking the story," Ruff said. "I think he's on vacation this week."

When Peter Baker, a young, workaholic White House correspondent for The Washington Post, arrived at Andrews Air Force Base for the trip to Moscow, NBC's David Bloom pulled him aside to ask about the second-intern rumor. "You guys are going with it, right?," Bloom asked. Baker explained that nothing, as far as he knew, was in the works.

On Clinton's last day in Ireland, Brian McGrory, a Boston Globe reporter, asked Baker, "If a reporter wanted to stay over for an extra day to play golf but didn't want to miss a big story, what would he do?" Baker said he would probably be safe.

As they were boarding the plane, Doug Sosnik asked Baker if the Post was about to break the story. On board, Mark Knoller asked if he should worry about filing a radio dispatch from the air. Baker began to hedge his categorical denials. While at first there had been no Woodward story, who knew what kinds of leads he was pursuing?

Every night around 10, The New York Times or the Los Angeles Times or the A.P. or CNN would call Lockhart at home, asking if the story was about to surface. The New York Post, the Fox News Channel, and Rush Limbaugh all publicly mentioned the rumors of a second intern. But, for the moment at least, the press had to content itself with just one.

"The White House lies about everything/' Mike McCurry said sarcastically. "Our credibility is zero."

Within the West Wing, top aides were so worried about their own credibility that they called reporters to say they had never knowingly provided bad information. Begala was downright angry over Clinton's conduct—"He looked me in the eye and lied to me," he told a friend—and considered not coming back after his August vacation. McCurry felt that it had been grievously wrong for Clinton to send him out to lie on his behalf. Erskine Bowles, the chief of staff, was deeply disappointed in his boss. Emanuel, who had lectured reporters for obsessing on the president's sex life, felt he had no choice but to accept Clinton's apology. Since they had all been tarnished and were largely staying off television, the administration's chief spearcarrier was now Lanny Davis, a raspyvoiced former White House lawyer. But Davis was disgusted with the stonewall strategy; he could hardly blame reporters for distrusting the White House in the face of a total information blackout. Davis himself kept getting stiffed when he checked in with his old friends in Ruff's office:

"Can you confirm the president was served with a subpoena?" They would not.

"Well, what am I supposed to say on Larry King or GeraldoT'

The tense atmosphere soon turned poisonous as the Hill was hit by a wave of sexual McCarthyism. Media outlets found reasons to trumpet old extramarital affairs involving three Republican members of the House: Dan Burton, Helen Chenoweth, and Henry Hyde, chairman of the Judiciary Committee, which handles impeachment proceedings. "Ugly times call for ugly tactics," said the on-line magazine Salon in revealing Hyde's 30-year-old relationship. White House officials adamantly denied leaking any of the stories, but McCurry grew nervous over reports that the president's lawyers had private detectives unearthing dirt on Judiciary Committee members. "If that's true, we're going to have a little exodus here, aren't we?" he told John Podesta.

"Yeah, and I'll be out the door ahead of you," Podesta said.

Soon the entire city was bracing for Ken Starr's avalanche of evidence. White House aides, determined to seize the initiative, began passing along tidbits from the president's grand-jury testimony: He had given Lewinsky gifts the last time he saw her. He had promised to try to bring her back to the White House from her Pentagon exile. It was one of the administration's battle-tested techniques, leaking compromising information with a sympathetic spin in order to pre-empt the investigators. Perhaps they could make much of Starr's report look like old news.

But the prosecutors could play the same game. Once Starr's office made known that its report on impeachable offenses would be delivered to Congress the week of September 7, the most graphic details began to dribble out in what the Clintonites viewed as an orchestrated campaign to destroy the president's reputation and drive him from office. NBC's Lisa Myers, whom administration officials particularly disliked for what they saw as her consistently negative scandal stories, reported that Clinton and Lewinsky had sex after the president had attended church on Easter Sunday. Reporters were even tipped off when Starr's 36 boxes of evidence were sent to the Hill, leading to the first live cable coverage of the unloading of a van.

Lockhart was disgusted by the deluge of leaks, which he considered contemptible and probably illegal; it was, after all, a federal crime for prosecutors to disclose sensitive grand-jury information. But none of the reporters would take on the issue; they were all panting after exclusives. One day an anonymous ABC staffer called Lockhart to say that ABC reporter Jackie Judd was getting material directly from Starr. Lockhart's caller ID showed that the person, clearly upset with the network's coverage, was in ABC's Washington bureau. Judd found the call "pretty disturbing." ABC had been bedeviled by leaks on the Lewinsky story; White House officials had learned more than once what was in Judd's script before she went on the air, and ABC executives had threatened to fire any such leaker.

The White House political team and the lawyers, who had been at odds for months, were debating whether to steal Starr's thunder by slamming his report in advance—a "prebuttal," in White House lingo. Some of the lawyers hated the idea. This was not how attorneys did business, Ruff said. What if they wound up responding to charges that weren't in the final report?

At 6:30 on September 10, the night before the House was scheduled to release the Starr report, Lockhart, Begala, Emanuel, Kennedy, and other senior aides gathered in Ruff's second-floor office to watch the evening news with Ruff's lawyers, Lanny Breuer and Cheryl Mills. Ruff fingered the remote control, flipping between ABC and an NBC feed out of Baltimore.

Here was Jackie Judd: "Ken Starr and his prosecutors accuse President Clinton of 11 offenses which they consider grounds for potential impeachment." She ticked off some of them, from count 1 (perjury in the Paula Jones suit) to counts 10 and 11 (obstruction of justice and abuse of power by invoking executive privilege).

And here was Lisa Myers: Also included in the report are lurid details of the president's encounters with Lewinsky One example, legal sources say, will be made public in the report, a sexual episode involving a cigar."

That sealed it. The lawyers had been angry about the leaks, but now they realized that leaks were their best friends. They knew virtually everything that would be in the report. After all, Judd and Myers had been aggressively covering Whitewater for years and always seemed to have a good pipeline to Ken Starr's office. Starr's zeal to screw the White House, Breuer concluded, had worked to their advantage. It was time to move. Ruff, Breuer, and Mills repaired to David Kendall's law office, a few blocks from the White House, and worked past one A.M. on a response to a report that none of them had seen.

Lockhart insisted on a deadline of 12:30 that afternoon, and six minutes before the appointed hour he began handing out the 73-page rebuttal. The timing was perfect; all the cable networks were live but had no news to report. The correspondents marched onto the North Lawn and began reading highlights of Kendall's attack on Starr. For two hours, until reporters got their hands on the independent counsel's 445-page report, the White House line dominated the airwaves. The spinners were surprised at how much coverage they had received. There had been so many leaks of Starr's evidence, from the infamous cigar to the president's oralsex-isn't-sex argument, that nothing, beyond Lewinsky's sad, self-absorbed tale of unrequited love, seemed shockingly new.

Mike McCurry and Paul Begala kept Pressing for details: Was the president angry? Did he lash out at the prosecutors? Did he storm out of the room?

It was September 18, three days before Clinton's videotaped grand-jury testimony would be broadcast to the nation, and Nicole Seligman, Kendall's law partner, was briefing them on the testimony in Ruff's office. But Seligman, reading from the notes she had scribbled, wasn't sure of the emotional temperature. Yes, there were some sharp exchanges, she said. Yes, Clinton once looked angry when they took a break. But she didn't recall any fireworks.

For days, journalists had been reporting that the tape would reveal Clinton in a purple rage. "Our sources say the president was not just evasive but profane, at times lost his temper, and at one point, stormed out of the room," said CBS's Bob Schieffer. Clinton had "exploded in anger," said the New York Daily News. It was not McCurry and Begala who had been pushing this line; the stories were floated mainly by Democrats on Capitol Hill, who had not seen the tape and were just playing the gossip game with reporters. But the White House spinmeisters made no effort to knock down the overwrought accounts. If the media wanted to prepare the country for a Clinton meltdown, so much the better. Over the weekend, Kendall's team leaked a more measured description of Clinton's testimony to The New York Times, but the idea of an impending doomsday had already taken hold. Critics were denouncing Clinton's attorneys for allowing the videotaping. Lanny Breuer's brother called to say, "Lanny, you're smart. How could you have done this? It was so stupid."

When the four-hour tape premiered on seven networks on Monday morning, viewers saw a president clearly uncomfortable, often evasive, gamely insisting that Lewinsky had had sex with him but he had not had sexual relations with her. He kept his anger in check, though, and people seemed to sympathize with the target of what appeared to be a sexual interrogation. Clinton's job-approval rating jumped from 59 to 68 percent in a CBS survey. There was talk of another Comeback Kid performance.

Begala felt they had turned an important corner. No amount of negative media coverage was going to convince the public that Clinton should be impeached. The president and his defenders had survived a thermonuclear attack by the press, and they were still standing. To hell with the Beltway blowhards demanding Clinton's scalp.

Rahm Emanuel was appalled at the R-rated coverage of Starr's report. A former ballet dancer and Chicago fundraiser with an almost robotic allegiance to the president, he often complained that Washington journalists were affluent insiders with little feel for the concerns of average Americans. The press liked to dress up the Lewinsky story with high-minded legal and constitutional ornaments, Emanuel felt, but here, when it counted, the reporters were gorging on the raunchy details. It really was, at bottom, just about sex. Clinton's wrongdoing was purely personal, and for all the journalists' disdain, most people got it. "The elite get more times at bat, but the public still has a vote," Emanuel would say.

The dark mood had lifted, and the Clintonites felt emboldened enough to step up their spinning. They loved to turn the tables by assailing their accusers. James Carville, the president's shoot-fromthe-lip pal and mastermind of his 1992 campaign, was magnetically drawn to such situations. It was Carville who had dismissed Paula Jones as the unfortunate result of dragging a hundred-dollar bill through a trailer park. The so-called Ragin' Cajun had been the chief lieutenant in the administration's war on Ken Starr; now he seized the moment by denouncing Newt Gingrich on Meet the Press. Clinton's allies were determined to make the impeachment inquiry look partisan by demonizing their favorite bogeyman, the Speaker of the House, and Carville was the perfect pit bull. While he often plotted strategy with the president, his outsider status gave him a veneer of independence.

"Get anyone you want to call me," said James Carville, "but I ain't gonna shut up."

"You can get the Holy See in Rome, the International Court at the Hague, you can get anyone you want to call me and it ain't gonna do any good, because I ain't gonna shut up," he said. Carville believed it was downright stupid not to make Gingrich the issue. He had been through this before when he declared war on Starr nearly two years earlier.

The president had asked that he cool it, and he briefly toned down his act. But Clinton later told Carville that he, the president, had been wrong, that the attacks on Starr had been smart politics.

Clinton soon began to despair that the press might not cover what was left of his political agenda, but McCurry and Lockhart told him not to worry. The cable networks were carrying most of his events live, hoping he would say something, anything, about Lewinsky. The staff decided to exploit such moments by having the boss recite a laundry list of initiatives. Clinton complained that he was boring his guests with this kitchen-sink approach, but the spin team was more interested in the television audience.

Foreign policy was their ace in the hole. When Clinton held an Oval Office photo op with Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat to announce modest progress in their peace talks, Emanuel asked NBC's David Bloom not to cast the event as a mere distraction from impeachment. "We know you're going to frame this in terms of Monica, but at least you could do us a service by getting our message out," he said. Emanuel believed the press would screw them either way: If the Mideast talks failed, it would be because the Lewinsky scandal had diminished Clinton's power; if they succeeded, it would be a desperate political attempt to change the subject. Emanuel was so sensitive about

Begala, who had been Carville's consulting partner for a dozen years, called to say that the White House viewed his latest antics as unhelpful. Carville was unmoved. Clinton's perceived weakness that when Washington Post reporter John Harris wrote a piece about the president's trying to cope with several crises at once, the man known as "Rahmbo" called to complain. As Harris tried to defend the story, Emanuel snapped, "I can't put up with this idiocy," and hung up.

Lockhart was disgusted that afternoon when MSNBC and the Fox News Channel largely ignored Secretary of State Madeleine Albright's discussing the Middle East talks but gave fuller coverage to McCurry's briefing, when reporters could again ask about Lewinsky. The cable executives, Lockhart believed, had obviously made a marketing decision to endlessly exploit the scandal.

The staged events continued. On September 30, the final day of the fiscal year, the president appeared in the Old Executive Office Building claiming credit for a $70 billion budget surplus, the first after 29 years of red ink. McCurry decided not to allow a photo op at the next event, a meeting with the Kennedy-assassination review board, to shield Clinton from the inevitable shouted questions about Lewinsky. When a reporter complained, McCurry shot back: "We were trying to put the focus on the surplus_We do that every single day— every single hour of every single day.... We offer up all kinds of stories ... and it's been Monica, Monica, Monica, Monica." This time, however, the budgetary boasting led the three network newscasts.

Two days later, transcriptions of Lewinsky's taped conversations with Linda Tripp were released as part of Starr's 4,600 pages of evidence. At 12:30 P.M., White House aides got one copy from the Government Printing Office, ripped it apart at the bindings, and distributed pieces to a half-dozen attorneys, who funneled their comments to Greg Craig, the new White House impeachment lawyer. Late in the afternoon, Craig walked onto the White House driveway to tell reporters that Tripp was the chief villain, the woman who had told Lewinsky that she should demand that Clinton find her a job in exchange for her lying in an affidavit.

The media assault was unrelenting. On the morning of October 7, Lockhart was furious at a front-page Washington Post story declaring that Clinton and A1 Gore were "personally leading an extensive last-minute lobbying effort" to persuade House Democrats to vote against the Republican plan for open-ended impeachment hearings. This was a crock of shit, Lockhart felt. The Hill was up in arms, and he had to spend the day reviewing the president's call sheets and insisting to reporters that Clinton had made only a handful of phone calls, some of them in response to lawmakers' calls. John Harris called to say that a memo he had given his Post editors had been hyped, but Lockhart was out of patience with these bogus stories.

When the House approved the impeachment inquiry the next day, reporters openly smirked at Lockhart's insistence that the president was focused on his job and not worrying about a legislative process that could cut short his tenure. Lockhart had been in the Oval Office that morning, listening to Clinton talk to French president Jacques Chirac about bloodshed in the Balkans. But the press, Lockhart felt, was too obsessed to care about anything besides impeachment.

The staff, for its part, spent the morning debating whether Clinton should personally respond to the impeachment vote. Some advisers suggested that Greg Craig speak on his behalf. But John Podesta and others said the magnitude of the moment required a presidential response. Lockhart warned that reporters would hound Clinton for days until he offered up a comment. They decided to allow a "pool spray," a brief question session with a small White House press pool, as Clinton convened a budget meeting in the Cabinet Room. A White House speechwriter drafted some remarks, but Clinton rewrote them in his own voice.

"It is not in my hands," Clinton said, sounding strangely detached. "It is in the hands of Congress and the people of this country, and ultimately in the hands of God." Lockhart tried to usher the reporters out, but Clinton took one more question, saying, "I have surrendered this." Lockhart was puzzled by the choice of verb. "What did that mean?" he asked his colleagues. Begala explained to Lockhart and Emanuel that it was a Southern Baptist expression, a matter of surrendering one's fate to God. The political team would still be fighting like hell.

The bottom-line White House strategy— perhaps the only available option at the moment—was to demonstrate that the president was immersed in his job while Congress was consumed with partisan bickering over impeachment. After days of marathon budget talks, Clinton managed to salvage some of his favorite initiatives, securing more than a billion dollars to hire the first of 100,000 new teachers. Clinton had won a political round, but that could not dispel the dark shadows. When NBC's Bloom reported the victory, he noted tartly that the president was trying to "focus attention away from upcoming impeachment hearings."

On Election Night, as he munched on pizza in Podesta's office, Clinton was thrilled by the Democrats' surprisingly strong showing. He exulted as political director Craig Smith showed the computerchallenged president how to pull results off the Internet. ("How do you make it go up?" Clinton asked.) None of the brilliant pundits had predicted that the Democrats would pick up five seats in the House. The voters were clearly sick of impeachment. But Carville told Begala and Blumenthal that they had to set up a "gloat patrol" to make sure nobody crowed in public. That, it turned out, was not a problem. None of the staffers touched the wine and beer. Begala called Emanuel to say they had been through too many highs and lows, had accumulated too many scars, to start celebrating now. ful of aides watched in his office as Henry Hyde announced that his Judiciary Committee would hear from just one major witness, Ken Starr. Lockhart stopped by to join the discussion. The incredible shrinking hearings were surely good news, but the consensus was that Hyde was still moving toward a vote on impeachment. The Clinton team remained nervous, and their ranks were growing noticeably thin. Mike McCurry was gone. Rahm Emanuel had just left, along with Erskine Bowles. Paul Begala turned down the chance to move into the cubbyhole office next to Clinton's and started making plans to leave. All had reasonable explanations about career plans, but all had clearly been wounded by the president's lying.

The week's drama was not yet exhausted. At 6:04 P.M. that Friday evening, Lockhart reached for the remote as he saw Tim Russert silently holding forth on MSNBC with some sort of breaking news. As the sound came up, he learned that Newt Gingrich had decided to quit. It was incredible; their arch-enemy, the man behind the impeachment drive, limping off the battlefield. A stunned Clinton called Podesta from Arkansas to talk about putting out a statement, which Lockhart felt passed the graciousness test—just barely. Lockhart told reporters that Gingrich's departure was a mixed blessing because many House Republicans had considered him too moderate. But the press, always hungry for a new story line, was declaring that Gingrich, not Clinton, would be the highest-ranking victim of the Lewinsky scandal. The journalists even bought the notion that Clinton was paying Paula Jones $850,000 to settle her suit because he wanted, in the administration's preferred phrase, to "move on."

Subtly, perhaps subconsciously, the White House strategists had managed to frame the debate around Bill Clinton's survival in office. If he dodged the impeachment bullet, in this view, he had "won." But that bit of sophistry ignored all that had been lost. The ambitious second-term agenda that Clinton had espoused a year earlier had been obliterated by the Monica mess. No amount of administration spin could disguise the scandal's collateral damage. The president had become an object of ridicule, a source of embarrassment for parents talking to their children. He would probably cling to power, but he could not erase the judgment of history.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now