Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowJOAN OF ARKANSAS

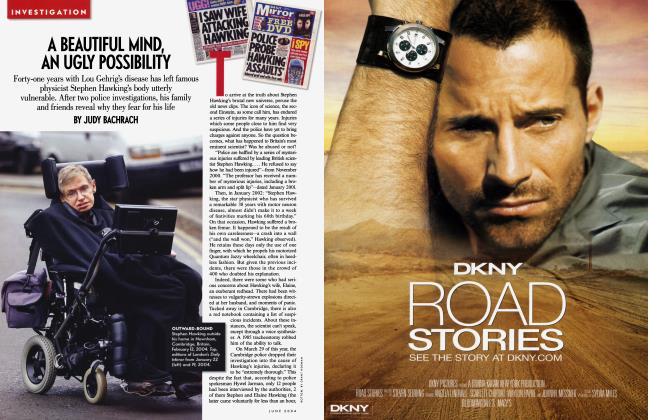

By defying Kenneth Starr—enduring nearly two grueling years in jail and facing perhaps a decade more for her refusal to testify before the Whitewater grand jury— Susan McDougal became a symbol of extraordinary courage and integrity Then even that hard-earned reputation was thrown into question when she went on trial for embezzling $150,000 from a wealthy Brentwood, California, matron, Nancy Mehta, wife of legendary conductor Zubin Mehta. With McDougal's acquittal, JUDY BACHRACH investigates the turbulent past and dramatic vindication of Whitewater's shackled martyr

JUDY BACHRACH

It is an amazing spectacle. In a narrow corridor of the Santa Monica courthouse, a squat modern building with a gorgeous view of palms and sparkling ocean, Susan McDougal is throwing a tantrum. Oblivious to practically everything and everyone around her, the only person in America to stand up to Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr lies prostrate on a wooden bench, her head tossing wildly. McDougal's dark, shining hair flails the thighs of Mark Geragos, her lawyer, who is seated beside her. "God! I'm gonna kill her!" she cries.

Those listening know whom she wishes dead—Nancy Mehta, a woman who has no connection to Starr, but who shares with him the desire to see McDougal behind bars. "I'm gonna punch her out!" cries the outraged defendant. Her small fists hammer away at the bench, then shift to Geragos's lap. "Just let me punch her out!"

Although she has been endlessly scrutinized by the media, McDougal remains an elusive and contradictory personality. Reticent and tactically clever at times, she can, without warning, turn bold, heedless, and explosive. Lately, she has been banging on tables, erupting unprovoked, and bursting into tears. You can understand why. Unlike the White House big boys—her longtime friend Bill Clinton, for instance, or his advisers Bruce Lindsey and Harold Ickes— all of whom have finally buckled under and testified before Starr, the 44-year-old McDougal remains resolute, silent and unbroken. She has adamantly refused to cooperate with the independent counsel, claiming that he wants her to ruin the lives of the president and First Lady by swearing that she witnessed crimes they never committed. She has even declined to shake Starr's outstretched hand. Because of this unflinching stance, Susan McDougal has become a national symbol of political defiance and been made to suffer as much as or more than anyone else in the Whitewater drama.

Cited for contempt, McDougal entered prison for the first time in 1996, wearing a short gray skirt, shackles, and handcuffs. Since then she has lost nearly everything she held dear: her health, her vitality, her liberty. She has experienced herniated disks and excruciating back pain, has been thrown into the same cellblock as some of Charles Manson's old gang of murderers, has been handcuffed to a courthouse toilet, has been stuck in solitary confinement 23 hours a day, and has been transported to court in cages.

"I can't remember a time when I wasn't indicted," she tells me. And her troubles are far from over.

In February, McDougal faces another trial for contempt and obstruction of justice in the endless Whitewater investigation. She may also face another jail term—up to 10 years—after enduring almost 2 years of prison. Uncowed, she intends to call Starr as her first witness. What does she have to lose? "Joan of Arkansas," old friends call her.

Now even that distinction is at stake. The charges against her in lovely Santa Monica have nothing to do with politics, obscure Arkansas land deals, or her friendship with the president of the United States. Here, in the courthouse with the million-dollar view, Susan McDougal stands accused of more venal crimes: forgery, embezzlement, and tax evasion. She says she is innocent of all, the victim of a woman who "ran her life."

Susan McDougal's enemy, Nancy Mehta, was once a beautiful starlet who played Darrin Stephens's former girlfriend on the old TV series Bewitched. She is now a wealthy 61-year-old Brentwood matron who still presents a voluptuous and dramatic figure. Her voice is deep and throaty. From Mrs. Mehta's long neck hangs a diamond pendant the size of a coin.

At Mehta's side is Deputy District Attorney Jeffrey Semow, a prosecutor in tight gray suits whom she invariably refers to as "my lawyer." Semow has a temper of his own. "That bitch!" is how he once referred—privately, he thought—to McDougal. Now he worries constantly that the judge or jurors will hear of his outburst.

Semow also worries about his star witness. Nancy Mehta, who believes McDougal embezzled more than $150,000 from her, happens to be the wife of Zubin Mehta, director-for-life of the Israeli Philharmonic, former director of the New York Philharmonic, and one of the world's wealthiest conductors. His circle of friends includes such musical celebrities as violinist Pinchas Zukerman and fellow conductor Daniel Barenboim. He is never far from the spotlight. It was Zubin who conducted "the Three Tenors" on their first hugely successful CD; it was Zubin who posed nude in a sauna for Paris Match.

It is Nancy, his wife of 29 years, who spends a good portion of his millions.

In the early 90s, one of the major beneficiaries of her largesse was McDougal, who became Mrs. Mehta's trusted chum and bookkeeper. Susan McDougal has told friends that her former boss meant to be especially generous with her. Airline tickets, hotel stays, expensive clothes, small vacations—these were McDougal's for the asking. She even claims she was permitted to sign Nancy Mehta's name on checks and a credit-card application. The unhappy wife, Susan insists, was eager to drain the bank accounts every month in order to hide her husband's money from his children, none of whom are hers. (One was the product of an affair between the conductor and a teenage violinist.)

Nancy Mehta, not surprisingly, has a different story. "I was screaming, screaming, screaming!" she tells me, describing her reaction upon discovering her beloved employee's alleged dishonesty. "She took far, far more than $150,000," the conductor's wife explains. "You know, Susan always used to tell me, The bay-est writers and storytellers ah from the South.' But where does that leave me? I don't know how to tell a story."

The details do much of the telling. The Mehtas have a talent for spending. The maestro, who, Nancy tells me, "thinks checks are just pieces of paper," managed to pay $45,000 for a tea set from Israel. His wife, as courtroom testimony makes clear, is a woman of frantic, if intermittent, generosity. She was happy to spring for a cousin's $100,000 wedding (complete with a pond of shimmering Japanese koi), but worried about the cost of raspberries. Together the Mehtas own five handsome houses in West Los Angeles and Malibu, and lease a villa in Florence. Their Brentwood mansion, peering over a hilly trail of Iceberg roses, jasmine, and aloe, once belonged to Steve McQueen. Inside, it is decorated in chintz, its dark walls warmed by the faint pink hues of hammered Incan gold.

It was in this extraordinary setting that McDougal, the displaced southerner, found herself a decade ago. The Mehtas had everything she did not—17th-century Florentine chairs, an $8,000 computer that looks like a makeup bag, a white RollsRoyce, and a nippy, ill-tempered borzoi (now deceased) named Tarras. McDougal claims that the dog devoured the most expensive cuts of Vicente's Market beef off the couple's Persian rugs. McDougal watched as her new benefactress paid for the plumber to fly to Italy; for a wedding cake to fly to San Francisco in the seat next to a hired cake guardian (Susan's younger brother); for a Christian Science counselor to travel, first-class, to New York to persuade Zubin not to leave the rocky marriage. Small wonder that in their household cascades of cash seemed to evaporate. "Nancy has never met a number she could get along with," says a source familiar with the Mehtas' finances. The Mehtas, I learn from law-enforcement officials, even tried to spring for the prosecutor's airfare to Italy so he could interview the conductor at his villa. Semow declined.

"I don't want to hear this as a vice, what we do with our money! That doesn't mean she has to steal from us!" Zubin Mehta snaps in the courtroom. He is wearing a beautiful navy blazer brightened by gold buttons. His pale French cuffs are adorned with cuff links, also gold.

The Mehtas had everything McDougal did not: 17th-century Florentine chairs, an $8,000 computer, a white Rolls-Royce, and a nippy, ill-tempered borzoi.

In Santa Monica the courtroom is packed. Yellow-haired ladies, trial regulars with nothing but time on their liver-spotted hands, are huddled next to right-wing columnist Arianna Huffington, pursing her orange lips. She is surrounded by Internet gossip Matt Drudge, the defendant's favorite Los Angeles rabbi, as well as her African-American pastor. The clerical advisers appear particularly bewildered: What is $150,000 to the Mehtas? Wiry did the state of California pursue the ease for five years?

Among the press Nancy Mehta has become a figure of fun. Can they seriously take the word of this imperious and fairly forgetful lady? Can they truly sympathize with a millionairess who declares, "I am not attentive to Visa and MasterCard or any of the cards I hold"? Can they identify with someone who, when questioned about a receipt found in her files, retorts, "I am not a filer!"? Or declares, "I am not an accountant!"?

Susan McDougal says flatly, "Nancy Mehta is ///." "I've never been ill in my life," Nancy says in disgust.

In fact, Nancy Mehta is a distinctive character, pampered but uncertain, destined, she believes, for her own public martyrdom. "I will be denigrated, torn apart," she informed me a few weeks before the trial. She then issued a careful warning concerning the defendant: "This girl is a very, very charming person. Oh, she will make you believe everything! Everything and anything. I have seen grown men swept away by this girl. I have seen it."

But there are, I notice in the courthouse corridor, cracks in McDougal's charm. There are times when it seems there are two distinct McDougals: the womshe and her intimates want you to know, and the one you end up knowing, despite them.

"Be mean, Mark! I want you to go out there and be mean!" the defendant instructs her lawyer as Geragos lopes off to crossexamine her angry former boss.

In preparation for the battle ahead, McDougal smooths the creases from her creamcolored pantsuit and gives her long hair a toss. She may be down, but she is far from disheartened.

"Susan always told me the whole trial would be over the moment Nancy opened her mouth," says a friend.

This is what the defendant is counting on.

"You know, I couldn't help seeing the notes you took on what my sister was saying earlier," says Bill Henley, Susan's older brother. Despite his mild tone, he is clearly incensed: he is Susan's watchdog, alternately nudging and snapping at the press. "'Be mean!' you wrote."

"Yes, indeed," I reply.

"Well, I'm going to make sure that it doesn't happen again!" He stomps off.

And it never does. She never slips up. During my formal interview with McDougal—the only one she's given recently— as well as in several other conversations, I get the distinct sense that her performance is calculated. McDougal's true self, it seems, is usually as carefully veiled as a politician's past. Asked about her experiences in jail, she smiles engagingly and replies, "I miss prison. In prison you feel each moment is so important. Each night in jail I'd go to sleep and find something special under my pillow. A note of thanks or a candy bar. It made me feel so alive!"

I tell her I have heard that during her incarceration in Los Angeles she had to wear a red uniform—the color used to designate convicted child-killers and other violent types. A former inmate claims that McDougal seemed singled out for punishment by especially vicious guards.

"Well, if I was singled out it was because I was Susan McDougal, someone they had seen on television and in the news," she explains. "And I thought the prison outfits were so beautiful. They were 60 percent cotton, and you know that's hard to come by. I tried to take one home after I was released."

McDougal, with her translucent skin and carefully plucked brows, is as conscious as any movie star of the disadvantages of being seen from an awkward angle. The instant we meet she leaps from a Jeep belonging to her fiance, Pat Harris, to envelop me in a bear hug. She repeats this performance on the first day of court in front of the prosecutor, tossing a look of contempt behind her like a grenade. Semow is a lonely fellow, without an adoring retinue. "I am very, very conscious that I am the bogeyman in this trial," he tells me.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 134

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 89

McDougal, on the other hand, sees herself as a genuine heroine in America. Clearly others do as well. This didn't simplify the jury-selection process at the Mehta trial. With each passing day the judge grew more frustrated, the prosecutor more livid, the pool of potential jurors ever more shallow. One by one, citizens expressed their deepest feelings about Kenneth Starr. To them, McDougal seems innocent by comparison.

"/ don't particularly like Judge Starr and was impressed she defied what he wanted."

"I saw her in chains. I thought, Why is she in chains? I was shocked because she hadn't murdered anybody."

'7 believe Ms. McDougal acted out of principle. She would rather go to jail than do something wrong."

"The sainted Susan McDougal!" bellowed the prosecutor after yet another excused potential juror took his leave (having mouthed "Good luck" to the defendant). For this outburst Semow was roundly scolded by Judge Leslie Light, a cranky Reagan appointee and—this is California, after all— a veteran actor from the now defunct TV show Divorce Court.

You can appreciate the prosecutor's dilemma. Although he voted twice for Clinton he is perceived as a Starr stand-in. Semow believes that the jurors dislike him. It is his opinion that McDougal is actually a sociopath, and Mrs. Mehta an honest, if troublesome, witness.

The quest for unbiased jurors dragged on with little progress. Finally, one man tempered his admiration. "I have respect for her," he said of the defendant, "but I am puzzled by the variety of charges against Ms. McDougal."

"Do you know the expression 'When it rains, it pours'?" asked the judge.

If Susan McDougal has seen a lot of rain in her life, much of it can be attributed directly to the first important choice she ever made. One of seven children, she was born Susan Henley to a Belgian mother and a tough army sergeant who ended up running a gas station in Camden, Arkansas.

Susan appears to have been pretty eager to flee this life. At 19 she met the late Jim McDougal, a brilliant scoundrel who also happened to be a political-science professor at Ouachita Baptist University in nearby Arkadelphia. She married him two years later in 1976. He was 40. In his autobiography, Arkansas Mischief, Jim McDougal describes his bride's family home as "ramshackle." He knew he was her ticket out. "I thought Jim McDougal hung the moon," she tells me.

But her husband was a recovering alcoholic, a man of domineering temperament and wild, fluctuating moods. Later the Henley family would learn, albeit not from his bride, that he was manic-depressive. "I told her not to marry the sonofabitch," recalls Bill Henley. "He used large words when he didn't have to. He dressed like some kind of dandy."

Even more impressive than his vocabulary and white suits were McDougal's political connections: J. William Fulbright, the senator who opposed Vietnam and who served Arkansas from 1944 to 1974, and Jim Guy Tucker, the state's future governor, were especially close to him. A third friend was the young state attorney general, Bill Clinton, and his smart new wife, Hillary. Jim McDougal did business with all these people. He was interested in deals—land deals, bank deals. Many made money, some in unorthodox ways. In Arkansas, however, politicians tend to view financial chicanery with forgiving eyes—particularly when it occurs among their peers. After all, in 1978 Clinton himself earned a paltry $26,500 from the state.

"I'd like to do something to help Bill Clinton," Jim McDougal declared to a business buddy more than two decades ago. "He's starving to death as attorney general." Soon after this declaration, the McDougals ran into their hungry friend and Hillary at the Black Eyed Pea restaurant. He told them about 230 magnificent acres that he had just discovered by the White River—a surefire investment deal, Jim promised.

The Clintons were thrilled with the notion of instant prosperity. They were already having marital problems, involving, among other things, sex, money, and Clinton's inability to arrive at events on time. ("I have to kick his ass every morning," Hillary once told Susan.) "Jim McDougal promised Hillary this would pay for Chelsea's education," explains Bill Henley. So the two couples became equal owners of the Arkansas acres Susan immediately named "Whitewater." She even wrote a cute brochure promoting the development, which read in part: "Clean rippling water and stepping stones—but it's really so much more. More than a place to live_ Serene, simple and honest."

The problem was, the Clintons never had the money to swing the $200,000 loan for the land; in fact, both couples had to borrow to make the 10 percent down payment. By the time Clinton became governor in 1978, the Whitewater investment had already started to go sour, and the friendship between the rising political stars and the McDougals became as strained as the Clintons' resources: the future First Couple claimed to have lost $68,900 on the venture; the McDougals, who by the end had to float the project alone, about a third more.

Susan had little use for Hillary. Jim McDougal's wife remained a perky small-town girl who never forgot her efforts to win over the statesman's wife: "Your parents must be awfully proud of you, married to the governor of Arkansas." Hillary's reply truly stunned her: "My parents think I should have been United States attorney by now. It's no big deal to be governor of Arkansas."

On the other hand, the handsome new governor liked Susan quite a lot. In fact, as reporter James Stewart points out in his book Blood Sport, he boasted to her about his sex life: "This is fun. Women are throwing themselves at me."

In those Arkansas days, Susan and Jim McDougal were the hot couple to know. "The blue sky is theirs, the mountaintop experience is theirs" is how Bill Henley describes the early years of his sister's marriage. "You begin to believe you cannot fall." In 1978, Jim bought a bank in Kingston, Arkansas, christening it the Madison Bank & Trust Co.; three years later he bought another, and named it similarly. The Madison Guaranty Savings and Loan was housed in an old laundry. The entrepreneur made his wife a stockholder. Susan, he claimed, "did most of the paperwork to win approval of our purchase."

Money was of no small consequence. For the McDougals it was always boom or bust. Mrs. McDougal bought a Jaguar, her husband a Bentley. For $600,000, Susan had the savings bank completely renovated, painted mauve, and redecorated Art Decostyle. A Madison affiliate she owned received $1.5 million for advertising services (work that federal regulators would later deem "questionable"). Jim hired three of his wife's brothers, fiddled with the books, lent heavily to himself, passed out cash to borrowers without equity—and engaged in an elaborate pyramid scheme to keep all his investment projects afloat.

"It was growing like a weed," says Henley, who worked for Madison. He now knows how it grew so fast. Jim McDougal, Henley says, "was taking major advertising money he was spending on one project," and shifting it to "one of the successful projects that I had. That made it look, in the books, like it was not nearly as successful."

And why would Jim McDougal do all that? "Because he was trying to juggle the— to make everything work," Henley hastily amends.

"We called it 'the Madison Bank of Socialism.' Because there was this idea we were all one big family," reports Pat Harris, who was employed at Madison Guaranty before his relationship with Susan began. "If you needed to make your payments, you'd just go in and get $5,000. Because you were owed $105,000."

Meanwhile, the McDougal marriage was becoming as messy as Mr. McDougal's banking practices. Mrs. McDougal found herself alternately bored and indignant. "Our marriage really seriously went on the rocks when we moved to Kingston. We were living in this small town, and there was nothing, really nothing, to do," Susan recalls.

"I was sitting in a house that for a good part of the time had no running water, O.K.? We had a big bucket in the kitchen, on the floor. One day I saw the dog lapping out of it—our drinking water!"

Furious, she turned on her husband, informing him she was going home to her mother. "Call me when you get running water," she said. She was tired of playing Eva Gabor in Green Acres.

Jim McDougal, for his part, learned that his pretty wife was having an affair with his friend Bill Clinton—or at least so McDougal claimed in his autobiography, which appeared shortly after his death in March 1998. It is a disquieting work, containing several accusations. Another is that Susan had an abortion without telling him. His exwife denies this as vehemently as she does the romance with Clinton. Jim McDougal broadcast his invented tale of cuckoldry, she says, in order to placate Ken Starr's sexobsessed investigators. Her take on the failed marriage is, in its own way, as peculiar as Jim McDougal's: "Four years is a fairly long time to have a great marriage," she says, deadly serious. "Four years. Four great years."

The relationship tottered on until the mid80s, while Susan drew large commissions for commercials she devised to celebrate her husband's land developments. (One of the more memorable featured her in tight pants, riding a beautiful white Arabian.) Meanwhile, Jim used his wife as a front to acquire illegally a $300,000 small-business loan from an investment company regulated by the Small Business Administration.

Under federal guidelines, disadvantaged borrowers are supposed to use the funds for a business-related purpose, and Susan McDougal signed a document swearing that this was exactly what she intended to do. Instead, the money was used by her husband to buy a development near Little Rock, and to retire some Clinton-McDougal Whitewater debt.

"Jim came to her saying, 'This'll help me get back on my feet,"' explains Pat Harris. "Their marriage was already over; she felt she should help him. And you know Jim McDougal. Whatever he asks for, he gets."

If Harris talks as though the engaging old con artist were still alive, that's because for him—for almost everyone in this drama, in fact—he still is, in a way. Susan's fiance, four years her junior, is a pale, gentle man; from his unfurrowed forehead sprout fresh tufts of hair. Even though he got his start in business more than a decade ago selling real estate for Madison Guaranty Savings and Loan, he hates Jim McDougal for what he did to Susan.

"Jim basically told her to go ahead and get out," he says. "He was tired of her."

Stepping into the breach, Pat Harris rescued the captivating, abandoned woman. In April 1988 he swept her off to California, where his new sweetheart fortuitously found a secretarial job working for Michael Hammer, the grandson and one of the heirs of Armand Hammer, founder of Occidental Petroleum. It was a job for which she was poorly qualified. (Indeed, to get it she wholly fabricated work experience on her application. One past supervisor was a certain "J. McDonald, ill—retired," who she noted had formerly headed the mythical firm Tucker, Smith, McDonald. An Occidental investigator phoned this person, Semow tells me, and was assured of the applicant's worthiness. "'J. McDonald' was Jim McDougal," the prosecutor explains, with a chuckle.)

The job at Occidental seems to have stumped Susan McDougal; it was a challenge. "She was out of her element here," reports an officemate. "She just couldn't do the work. At the time she was working for Michael she was a blonde. She said she didn't mind being seen as A Dumb Blonde."

Hammer, says this source, picked McDougal over far abler applicants, despite her clerical deficiencies. This is the sort of gallantry Susan seems to invite at every crisis. Mark Geragos, her lawyer, is representing her in three cases pro bono; Harris, also an attorney now, works tirelessly on her behalf.

You could perhaps argue that Harris has something to compensate for, as he once, inadvertently, did his fiancee a bad turn. In the summer of 1989, during McDougal's bumpy secretarial career, he introduced her to Nancy Mehta, a former Elvis Presley co-star (as Nancy Kovak) and a proprietress of luxury rental houses. These properties, let for as much as $18,000 a month, drew such discriminating tenants as Tuesday Weld, Tom Hanks, and Marsha Mason. Harris, who had managed the houses, was entering law school. He warned his girlfriend not to take his place. Nancy Mehta, Harris observed, had "started showing some unusual characteristics."

Like what? I ask him.

"She told me one time that she was the reason the Berlin Wall had come down," he recalls dryly. "And I, uh, was surprised, so I said, 'How was that?' She said she and Zubin were touring and they met Gorbachev and she took him aside and suggested the countries could get along and all they needed to do was communicate better. And right after that he came out with perestroika."

Around the time she became friendly with Nancy, Susan was abruptly fired by Hammer. (In court she insists she was merely offered a "lateral transfer," which she found unappealing.) She had spent less than a year on the job, and her office peers never were told what precipitated her departure. An astonished Occidental employee recalls tears streaming down the silent McDougal's face as she left the building. So McDougal was very much at loose ends. As for Nancy Mehta, she also was very much in danger of being fired— from her marriage.

In the late 80s, Zubin Mehta, who travels extensively and has an eye for the ladies, fathered a son by a 17-year-old Israeli violinist. He informed his distraught wife that he wanted a divorce; she begged him to stay. Nancy Mehta believed she had found a sympathetic confidante in Susan McDougal. Over a long lunch, the two women chatted away. The refugee from Little Rock was offered a job that paid $15 an hour.

Then, says Harris, "Nancy invited her to go shopping and bought her $2,500 worth of clothes from Neiman Marcus and Saks." When her new employee objected, he adds, Mehta absolutely insisted on the purchases. "This is something I really want to do. You need help with your clothes. You told me you need help with clothes."

In other words, it was love at first sight.

In all Susan's many close and confidential talks with her new boss, Nancy Mehta tells me, there were several things left unsaid. McDougal never mentioned that she had defaulted a year earlier on her smallbusiness loan, for example. Nor did she confide that the development secured by her husband, Jim, with the fraudulent loan had gone into foreclosure, or that he had suffered a severe stroke after Madison Guaranty had been declared insolvent, requiring an estimated $65 million taxpayer bailout. Unmentioned, too, was the fact that she and Mr. McDougal had been partners with the Clintons.

On the other hand, Nancy Mehta tells me, "Susan did say, 'I used to run Bill Clinton's campaign when he ran for governor of Arkansas.'" Mehta didn't consider that an actual lie. "I knew she was painting, as young women do, in broad strokes." (McDougal denies saying this.)

Nancy Mehta's lawyer, Grant Gifford, does recall hearing the young woman discuss "a trial where Jim McDougal was acquitted. She said she had to go back and testify." (This was in 1990, when not only McDougal's ex-husband but also her brothers David and James were tried on charges of sham real-estate transactions connected with Madison. All were exonerated; charges against one were dismissed.)

"Testify about what?" asked Gifford.

"Oh, about a bank," McDougal replied vaguely. Gifford wasn't too interested. "I thought maybe she was a bank teller."

But the Mehtas discovered a bit more about McDougal later that year when Susan said she could take care of Nancy's bookkeeping. It was a chore that would double her modest pay and one she could easily perform. "She said she and her husband had run a bank in Arkansas," Nancy recalls. ("Yeah, but did she tell you they'd run it into the ground?" the prosecutor asked his star witness the first time she told him that story.)

The Brentwood matron was so enraptured with her new bookkeeper that Susan was kept steadily supplied with batches of checks pre-signed by Nancy Mehta. To be sure, there were small problems. A number of Mehta's checks, as it happened, were used for purchases in Little Rock, a city Nancy doesn't frequent. These, however, McDougal grudgingly repaid.

Then, too, there was the matter of Susan's appetite: "I'm always feeding her," the conductor's wife complained to another of her employees. "Is it right?"

"You don't draw the line," she was warned. "It's your fault."

Indeed, the line between acceptable and impermissible must have grown hopelessly blurred for McDougal. There were gifts from her boss of Ralph Lauren jeans. But Susan took things a step further, beginning to wear outfits belonging to her employer when Nancy Mehta was away. Although the conductor's wife testified—perhaps fatally—that she "never" allowed anyone else to sign for her credit-card purchases, both the houseman and her own cousin were given the privilege. ("I thought she would show [the card] to the vendor, but not sign," a troubled Mrs. Mehta explains as the puzzled jurors burst out laughing.)

Susan McDougal began to use Mehta's credit card for practically everything her heart desired: restaurant dinners, clothes from Saks, a hotel in Arkansas. The first year, Semow alleges, she charged $38,000 worth of items. The next: $52,000. By the third year she was still going strong—until she was fired.

McDougal never truly set out to steal from her boss: of this the prosecutor feels certain. Semow thinks she simply took advantage of opportunities that arose. Prone to gestures of staggering munificence, Nancy Mehta was a magnificent hostess who welcomed strays from Arkansas and elsewhere. In 1989 a hired dog-walker, who had been staying at the Mehta estate with her granddaughter, left abruptly. After asking permission, Nancy Mehta took in the girl, a 12-year-old African-American named Darla, whose thick hair she proceeded to iron (and burn). Then she sent her off to the finest boarding schools and camps. The young woman still lives with Mehta. ("I once read an article about this woman in Indonesia who spoke of helping others, how to uplift mankind," Mrs. Mehta tells me by way of explaining why she took the child in. "And—I hope I don't embarrass you—I began to pray. And then Darla came along ... ")

"We are both exceptional women": this is what Susan McDougal claims her buoyant employer used to tell her. The hair of the two women, McDougal tells friends, was colored and styled in exactly the same fashion by Nancy Mehta's own coiffeur: indeed, McDougal was once mistaken for her boss by a neighborhood shopkeeper. McDougal never bothered to correct him. Perhaps she shared some of his confusion.

Meanwhile, two of the men in Susan McDougal's life were causing problems. In March 1992, when Bill Clinton was a presidential front-runner, her ex-husband started talking about the Clintons to reporter Jeff Gerth of The New York Times. This launched an avalanche that would become the Whitewater scandal. Deeply angry that his old friend Clinton had abandoned him in his lean years, Jim McDougal was willing to do and say just about anything: "He offered me money to verify [what he had told Gerth]," says Bill Henley. "If Jim could bring down a president, it would have meant the world to him," explains his former wife.

Also disturbing to her: month after month, Pat Harris was demanding her fulltime presence by his side at his Michigan law school.

"I just can't, I just can't!" Susan McDougal protested. In Israel, Zubin was filing a paternity suit, seeking more visitation with his out-of-wedlock son, then three. Nancy, Susan explained to both her boyfriend and her older brother, was suicidal. ("I never used that word!" Mrs. Mehta insists.)

Harris grew angry. "Susan, this is not going to end well."

Susan McDougal—albeit for other reasons—believed he was right. Pat Harris readily concedes that on vacation in 1991 his fiancee confided that she owed her boss a sizable sum of money. Specifically, he told the court, McDougal admitted that she "may have charged more than she was owed [by Nancy Mehta] and when she got back she would have to work until she made it up." McDougal realized, he added, that she would have to "stop making personal purchases." How much she felt she owed the Mehtas no one close to her will say, but supporters indicate a considerable debt existed. When asked to give a figure, Bill Henley replies: "I'm not going to go there. I'm not going to get into that. This should have been at best a civil case."

On July 22, 1992, Susan McDougal's worst nightmare came true. Returning home from a visit with Harris, McDougal was asked by her employer to attend a morning meeting at the Brentwood estate. Present were lawyer Grant Gifford and an accountant. Nancy Mehta explained that she had just received a strange call from BankAmerica MasterCard, warning her that she had exceeded her $10,000-a-month limit. This was news to her, said Mehta, who hadn't even known that she held this particular card (or that her name on the application had been signed by someone else, or that McDougal was her co-signer).

"I haven't had breakfast," the cornered employee retorted. Mehta went to fetch orange juice.

"Susan's demeanor was pretty cool, not surprised," recalls Gifford.

McDougal explained that the card was used to buy items for the rental houses.

"That's not the case, Susan," replied Mehta.

(Subsequently, Gifford recalls, McDougal changed her story, insisting that the credit charges were simply Mrs. Mehta's quaint way of paying for her accounting work.)

Late in the morning, as she got up to leave forever, the younger woman promised a reckoning. "I have probably used this for more than I was owed. I probably owe you something. And I will give you an accounting" is what Gifford recalls her saying. "I am very sorry for the trouble I caused. I will make it right."

Then something astonishing occurred. According to McDougal, Mehta embraced her paid friend, saying, "Don't worry, darling, everything is going to be all right." With that, she gave her fired employee a pretty green leather purse from Italy. ("That was the other Susan I was kissing goodbye," Mrs. Mehta later told an acquaintance. "The loyal Susan.") Then Mehta waited for some reasonable explanation of the credit-card charges from her friend. No satisfactory explanation came, she says.

She went through her checks. "I was shocked, I was just blown away," Mrs. Mehta recalls. "A cumulative momentum of forgery and stealing! So I went to the police."

"And they yawned," says Mehta. "They thought, Another stupid case."

So it was Mehta who hired a detective to locate McDougal: as it turned out, she was at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee. Once again, she had lied to get a job, claiming she had worked previously for Governor Bob Riley—but making no mention of her years in Brentwood.

In other words, nothing was "all right." Mrs. Mehta knows this all too well. "What do I have to gain from this? I have lost a great deal," she tells me. "A great deal."

deep in the Susan McDougal files at Santa Monica courthouse there is evidence that Mrs. Mehta's confidante was offered a bargain, namely reduced jail time if she repaid the missing money. How much McDougal owed, however, was the subject of serious dispute. One law-enforcement source claims that Nancy Mehta's former pal was "morally offended" by the thought of paying $150,000 to the Mehtas. But that was the sum Semow demanded.

There may have been an incentive to bargain. According to two pages of scrawled and typed notes in the court file, which appear to have been written by an observer close to the case, an earlier McDougal lawyer was worried that his client might face jail, even if her defense—that Nancy Mehta wanted her to make big creditcard purchases as payment for her accounting chores—should prove convincing to jurors. (If McDougal's contention is true, she is faced with the question of why she never reported the charges as taxable income.)

"C[our]t feels this is a prison case if Defendant] convicted," read the notes. "Thefts go over for long period, much deliberation, sophisticated, conscious stealing. Tax fraud looks like a slam dunk. If DA can get restitution] up front, will not seek prison."

McDougal's earlier lawyer, Leonard Levine, was unaware of any stories about Mr. Mehta's illegitimate children or the money that Mrs. Mehta allegedly wanted to keep from them. "I don't see how it's related—at the time I was representing Susan, that topic never came up," he tells me. Negotiations on the subject of the repayment eventually stalled. Henley recalls his sister's reaction to the idea of admitting to a felony: "Hell no!"

So a costly trial became inevitable. Members of the Los Angeles Police Department began scrutinizing the Mehtas' financial records: it was hard work figuring out what McDougal took. "She steals big and she steals little," says an insider. There were allegedly forged checks and pre-signed checks. There were plane tickets to Dallas as well as a $100 Mehta check cashed by McDougal at the local food market. Nancy Mehta was impressed by all the labor Semow and a detective put into their investigation. "I think, What can I do to honor their assiduousness? It took such a long time."

Years passed. The Whitewater scandal threatened to engulf Susan. An independent counsel was appointed to examine where the business lives of the Clintons and the McDougals intersected. By the mid-90s, when it looked as if Susan McDougal was going to stand trial for embezzlement in the Mehta case, she was no longer an obscure country girl.

She was, in the eyes of many, a media star, the rebel McDougal from the headlines. As late as one week before the Mehta trial began, McDougal's new lawyer was still trying to bargain with the prosecutor, says a law-enforcement insider. "Geragos wanted to plead her to misdemeanor tax counts, one count of income-tax evasion," recalls the official. But when McDougal refused to concede embezzlement, negotiations again broke down. "The issue was her vanity. She would have a lot of trouble now admitting she's nothing more than a common thief," says the official.

One thing becomes clear during the Mehta trial. The new Susan McDougal is very much at home in the courtroom. Clerks and guards are greeted like old friends. Her testimony includes bits of spicy information that have never been inquired into by her attorney or the D.A.: the unhappy life of Nancy Mehta intrudes on the narrative McDougal delivers from the stand, as does her own suffering during Whitewater—a reference that has been forbidden by the judge, who thinks it irrelevant to these proceedings. In vain does Judge Light scold McDougal for her " Ulysses stream of consciousness." The jurors laugh, flash McDougal small smiles of encouragement.

Indeed, a few of the sums McDougal is alleged to have received improperly are easily explained by the defendant and should never have been brought up by Semow. Others are of legitimate concern—not that the people in her audience notice. They appear as enchanted as Nancy Mehta must have been when she handed over her checkbook.

"Gradually, gradually, more and more I signed her name to checks," explains the defendant, moving away from her own lawyer and turning her open, agreeable face directly to the jury. "I did it in her presence. I did it with her. She knew." McDougal says she was there to carry Nancy's cash for her in order to pay parking attendants. She signed her employer's name to credit-card receipts, she claims, when Mrs. Mehta was too vain to wear reading glasses. McDougal lays particular stress on her old employer's extravagance: a $10,000 florist's bill, the $720 wedding cake. She is effectively setting up a middle-class alliance with her jurors.

"If we had excess cash, Nancy wanted it out of the bank," McDougal explains eagerly. "She told me, 'Zubin would spend it.' She said he was very generous and would spend it on his children." (Nancy Mehta denies this: "There's no way I would take any money from my husband," she says.)

McDougal's chores, such as they were, were of a peculiar and confidential nature. Together the women compiled an unusual telephone directory for Mrs. Mehta: "She wanted to have the number of the bathroom of the King of England," says McDougal, as well as "the number of the car phone of the Russian diplomat of Washington." The new friends went shopping together "every day, going through stores like tornadoes," McDougal tells jurors. At night they went to the movies, to restaurants.

Perhaps there was too much proximity. "More and more," the defendant explains, her new employer "controlled how I looked, who I spoke to, what I wore." McDougal claims the dying of her hair by Mrs. Mehta's colorist was especially sinister—yet another manifestation of Nancy's authoritarian ways. "I'm a blonde" was McDougal's horrified realization after the hairdresser was finished. She recalls this with a delicate shudder—conveniently forgetting that she'd been one just months earlier when she worked for Hammer.

Then Susan McDougal adds, quite gratuitously: "In the two and a half years I worked there I never saw a friend come to the house—of Nancy's. Never! Zubin had friends who would drop by. But as far as a girlfriend—I felt I was Nancy's friend."

Tears moisten McDougal's cheeks as she surveys the jury. "I felt at times I was her only friend." ("My friends are calling me nonstop!" Nancy replies, deeply stung. "I just don't have tons of personal friends." She is talking to me from her Brentwood home. Although she vowed to be in court each day to watch Susan's testimony, her absence is conspicuous. "My lawyer ordered me not to come to court and watch," she sighs. By "my lawyer," she means the prosecutor.)

Semow explains in a private moment that the constant presence of blonde, prosperous Nancy in the courtroom would only aggravate the jurors' sense that McDougal is a hounded creature, pursued by several enemies. And to some extent, one law-enforcement official guesses, that isn't so far off the mark. "I think this is Ken Starr's fault," the official says. He is sure that but for the independent counsel's badgering her all those years the case would have been resolved without a trial. "But then Ken Starr started screwing around with all this contempt stuff. She's got all this contempt shit thrown at her. So she got her hackles up."

As if to drive this point home, actor Edward Asner (Mary Richards's old boss) unexpectedly pops up in court one day to hug the defendant and proclaim: "It's a continuation of the Ken Starr saga.... She did not knuckle under."

"My hero!" cries McDougal.

Even the judge has gotten into the spirit of things, throwing out 3 of the 12 counts against the defendant. Semow, says Judge Light, has failed to show that McDougal embezzled more than $50,000.

'McDougal felt it was coming at her from all sides," says Bill Henley of his sister's feelings when she, Jim McDougal, and Arkansas governor Jim Guy Tucker were indicted on Whitewater charges in August 1995. At the trial in Little Rock a year later, Susan McDougal did not testify—but her ex-husband did. The fraudulent loan signed by his wife—which fetched him $300,000—he called "Susan's deal ... her undertaking."

One government witness, a businessman named David Hale, who had made the loan, insisted that Bill Clinton was present when the deal was discussed—indeed, wanted some of the money. (Clinton has flatly denied this; Jim McDougal would eventually claim that Clinton pushed the deal so that Susan could get some cash.)

On May 18, all three defendants were found guilty. It was Starr's first Whitewater victory and a major score for him in Arkansas. His people repeatedly urged Susan McDougal to confide in them. Jim McDougal, facing a threatened 84 years in jail, became Starr's lead singer.

"This will be very painless: this is all you have to do," McDougal recalls her exhusband advising. Susan had to admit to an affair with Clinton, her former spouse told her, because "[prosecutor] Hickman Ewing was driven crazy by the sex part of Bill Clinton's life.... And that would get you leniency."

"Hey! No way am I going to do that," Susan McDougal claims she said.

She also heard, she says, from Starr prosecutor Ray Jahn, who had ideas of his own: "Back up David Hale! Give us Bill or Hillary Clinton!" If she resisted, she claims to have been warned, she would face a federal tax indictment. But McDougal said she honestly didn't know of a single crime either Clinton had committed.

"Is there anything you can tell them— even if this [allegation about Clinton] isn't true?" asked McDougal's mother, Laura Henley.

"There is nothing," said her daughter.

When all else failed, McDougal's estranged spouse confronted her yet again. In his days as a flush Arkansas banker, he had given Hillary Clinton a fat, $2,000-a-month retainer for what he considered minimal legal services. (McDougal's autobiography calls the fee a "subsidy to Clinton.") This payment, Susan McDougal's ex-husband told her, very much intrigued Starr.

"I know you don't have any great love for Hillary, and Hillary is who they're going after, really," Jim McDougal told her soothingly. "It's really Hillary we're going to give them."

But even for a reduced sentence, Susan McDougal couldn't manage to brand the First Lady a bribe taker. "I don't think it's illegal for a friend to give a friend work," she says with a sigh. "Jim was totally trying to find something that he could use to be The Big Witness. It would have made Jim's life to be Monica Lewinsky. You know—to be on every television, every newspaper."

"I want a place in history and this is going to guarantee it," Jim McDougal pleaded, begging his former wife to cooperate.

It is one of the ironies of this story that Susan McDougal is the one to whom that place will likely be granted. From the judicial system she got a two-year sentence for signing the misleading loan application, 18 months for refusing to testify before Starr's grand jury—and a reputation for boundless courage.

In 1997, during "his last, bitter days," as Susan McDougal calls them, her ex-husband didn't speak to her at all. Instead, shortly before he went to jail, he talked to the prosecutors ("Starr had a trustworthy look" went his rationale)—and to Larry King: "I have hit rock bottom," he declared, without exaggeration.

The former banker was living in a trailer, supported by a monthly $591 disability payment from Social Security. He suffered from blocked carotid arteries. For days on end he sat in his armchair, the television always on. The small table on his left was piled high with medications; on his right was a stack of candy. He was tired, angry over his ex-wife's reluctance to trash the president, who, he insisted, "wouldn't have fixed a parking ticket for her."

But his former spouse says her stance with Whitewater grand juries—she has stonewalled two so far—has nothing to do with affection for Clinton. Susan McDougal is worried about herself. She fears perjury charges if she contradicts Hale's testimony. She has also considered the humiliating fate of young Monica Lewinsky. "You know, she has to keep going back and saying more," Susan McDougal tells me. And, finally, McDougal has thought about her ex-husband, so garrulous with Starr and his men. He told everyone, for instance, that he'd asked Clinton to pardon her. ("You can depend on it," the president supposedly replied.) Such a lie, she thinks. Even these days, he manages to make her angry.

Other times she's just mad at the world. "Jim had a right to be chicken if he needed to!" she shouts at me. "I didn't feel like my family or myself ought to make him hold to our standard—my standard of taking whatever came and standing up for what I believe to be the truth. Because he wasn't strong enough! He never was strong enough!"

This past March, Jim McDougal died in solitary confinement at the Federal Medical Center prison in Fort Worth, Texas. He was 61. He had been punished for failing to provide a urine sample for a drug test—a function he said he was physically unable to perform straight away because of medications he was taking for various ailments. When he suffered a heart attack, there was no one around to give him his nitroglycerin.

As for Susan McDougal's time in jail, the welcome she remembers at Sybil Brand (a now defunct women's facility in Los Angeles) was this: "You found yourself a prison, baby." Then the door slammed on her new six-by-nine-foot cell. She stayed in isolation, her only companions the cockroaches. "They beat me to breakfast," she told a reporter who phoned. Her brother Bill, on an early visit, said he waited for her five and a half hours, watching as later arrivals were ushered in.

When he was finally allowed to see her, he recalls, she was "in leg-irons and chains. They cleared an entire room for her. She told me they still had not brought her a Bible to read."

"Why is my sister being treated like this?" Henley asked the watch commander.

"It's because of who she is and the weight of the evidence against her," he says he was told.

In July 1997, after 10 months of such treatment in two different jails, the American Civil Liberties Union intervened; McDougal was moved to a federal detention center in Los Angeles. It wasn't Brentwood, but at least she was allowed to mix with the other inmates.

In her new environment, McDougal became a prison leader. "I was the Welcome Wagon lady," she explains briskly. She was also the local ward heeler, demanding extra medical care for the sick, badgering friends on the outside for jobs and shelter for inmates about to be released. Among visiting clergy, she became the favorite: a local rabbi brought her strawberries on Passover; she was befriended by a nun.

"She had quite a band of followers," recalls Carlotta Allum, an Englishwoman jailed for bringing the drug ecstasy into this country. "The first night I was there, she gave me some knickers and a bra." On discovering the new prisoner was pregnant, McDougal insisted she get double portions of food. "Because Susan would speak up, the guards didn't like her," she explains. "One of them came and took all her clothes out of the cell. You can't grasp how awful it was."

"I would think, If people only knew her they would know what an honest and good human being she was," says Patti Rowe, a cellmate, who had been convicted of creditcard fraud. "Every week Susan would go from room to room asking people—and there are an awful lot of people there— 'What do you need? What can I get for you? Do you need cigarettes? Need soap? Shampoo?'" McDougal would put all purchases for the indigent or those unwilling to pay on her tab, says Rowe.

Last spring, McDougal went to Rowe in great distress: "They're going to bring me before a grand jury again. I can't do it! I just can't do it. It's going to start all over again."

Her lawyer was worried. By now McDougal had already served more time than any other Whitewater defendant. But Geragos knew it could get much worse. "You're looking at a situation where you're facing 5 to 10 years," he said.

Time was becoming ever more of a concern to his middle-aged client. "Maybe I can have a family," she said wistfully to her fiance. But there was something she needed to do first: challenge Starr in the courtroom.

"We got to put this guy's feet to the fire," she told Harris. If she was going to be tried for contempt once more, she told him, she'd have her attorney call Starr to the stand, then his top prosecutor, Hickman Ewing.

In May, McDougal flung her defiance at a prosecutor questioning her before a Little Rock grand jury: "Mr. Starr should resign! That's my only answer to you." Even a question about her place of birth received no response. As she exited the courthouse in handcuffs and shackles, McDougal spoke with reporters: "I tried to explain to the grand jury my position and I hope they understand."

They did not. She returned to jail in shackles.

Two months later, in July, she was unexpectedly released. For the moment she is handcuff-free. U.S. District Judge George Howard Jr., citing the defendant's bad back and time served, said he had decided to lean "to the side of compassion and mercy." For once, McDougal's silence was the result of pure delight. Then she rallied, telling her liberator, "I am a much better person today than the one you sentenced. I promise you, you won't be sorry."

It isn't hard to decipher her words. The young, eager woman who remodeled banks, wore her employer's clothes, signed her checks, and ate her raspberries was yesterday's McDougal. The Mehta jury said as much. On November 23, McDougal—dressed in her favorite white pantsuit—was acquitted on all remaining charges. "Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you," she cried before falling into the arms of her lawyer.

Patti Rowe recalls old prison talks with her friend: "She said to me several times, 'You know, in my life I have lied. I have hurt people and done things in my past that I am not proud of. But there came a point when I had to say, "No more.'"" Rowe pauses. "She told me, 'I had to be honest. I had to say, "This is it. This is the defining moment in my life.'""

So, however unwittingly, the independent counsel has performed a remarkable deed: the moral transformation of his most implacable opponent. That opponent doesn't live in the White House. Perhaps—who knows?—Starr will be asked some questions about his role in the strange and difficult odyssey of Susan McDougal.

"This man is going to have to answer in a court of law for what he did," Susan McDougal promises.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now