Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

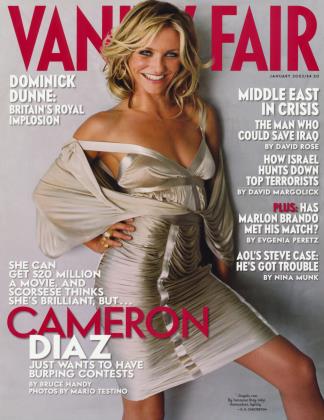

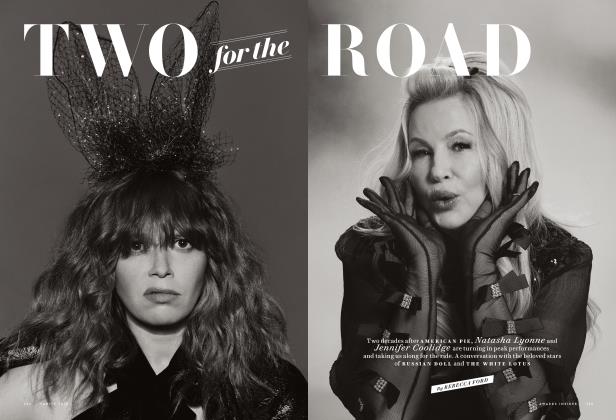

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAfter the trial of Princess Diana's butler, Paul Burrell, was halted by the Queen, one mystery remained: why was he prosecuted, given all the ugly secrets he knew? In London, DOMINICK DUNNE learns of the vendetta behind Burrell's arrest, the Palace's scramble to keep the lid on an alleged 1989 rape, and the tape Diana made of the rape victim

January 2003 Dominick DunneAfter the trial of Princess Diana's butler, Paul Burrell, was halted by the Queen, one mystery remained: why was he prosecuted, given all the ugly secrets he knew? In London, DOMINICK DUNNE learns of the vendetta behind Burrell's arrest, the Palace's scramble to keep the lid on an alleged 1989 rape, and the tape Diana made of the rape victim

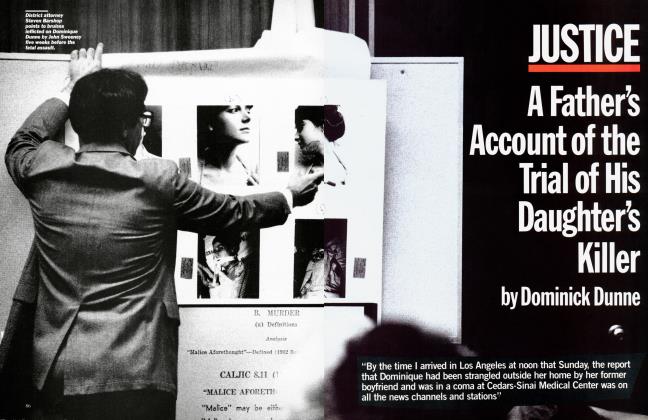

January 2003 Dominick DunneYou wouldn't believe how classy the trial of Paul Burrell, the butler of the late Diana, Princess of Wales, was when it started, although why anyone ever allowed this fascinating fiasco to get started in the first place defies imagination, but we'll get to that. As an American who frequently writes about criminal cases, I was thrilled to cover my first trial at the Old Bailey in London, as part of a limited cadre of print and television reporters in Courtroom No. 1, where some of the greatest trials in English history have taken place. The Old Bailey inspires reverence. The defendant sits in the raised dock in the middle of the courtroom, with a guard in attendance, for all to see. There is a stairway to a cell below, but the defendant in this case, who was on trial for stealing more than 300 of Diana's possessions, was never a prisoner. He moved about with the rest of us, wearing Turnbull & Asser-looking shirts and ties, and ate in the commissary where we had lunch. Protocol in the courtroom was very formal. The lawyers wore black robes and those little white wigs whose significance I had never quite understood. The point of them, it was explained to me, is to put the Crown, meaning the prosecution, and the defense on equal footing. The judge's name was Anne Rafferty, but she was always referred to with the greatest deference as Mrs. Justice Rafferty, and the lawyers, when they addressed her, referred to her as "Milady." A small but commanding figure of 52, Judge Rafferty wore a scarlet robe with wide strips of ermine on the sleeves. She also wore the little wig. Whenever any of us had to leave the courtroom while the trial was in session, whether it was to go to the bathroom or a television interview, we had to stop and bow our head to her. Once, when people were talking as she was leaving the courtroom, she turned with an icy glare that silenced the room, and then proceeded to her chamber. But no matter how classy the case had started out to be, it ended right at the bottom of the cesspool, with royal revelations guaranteed to ruin the glory of the Queen's Golden Jubilee.

"You wait," one of my new British media friends said to me. "The rape tape is going to become the story."

What a can of worms these grand folks opened to bring down a butler, who they thought had gotten too big for his britches and taken things from the palace where he had been the Princess's closest confidant for 10 years. It was as if the royal family, known as the Windsors, and her blood family, the Spencers, still did not realize—even after participating in what was possibly the most publicized funeral in history—that the drawing power of the late Princess of Wales continued undiminished five years after her death and will probably never abate. She was led like a lamb to the slaughter in a fake marriage that everyone was in on except her, and she is still getting even. Sailing up there on her broomstick, as they say about her, she took over the whole show. During the two weeks I was in London, there were more photographs of Diana in the newspapers than of the Queen or anyone else. The Windsors may have stripped her of her royal title, but anyone could have told them that they will never obliterate her memory as one of the outstanding legends of English history, a latter-day Anne Boleyn. As for the Spencers, couldn't someone have advised them that, no matter how desperately they wanted the uppity butler to do time in prison, the secrets he was capable of revealing could bring disaster down on them? This story has sunk so low in disgusting details that we now even know that Prince Charles had his valet hold the bottle when he gave a urine specimen during a stay in the hospital.

Paul Burrell's alleged criminality never made sense to me. This man's loyalty to the Princess had been so great that he flew to Paris after her death in the car crash with Dodi Al Fayed, helped prepare her body, dressed her corpse, and maintained a vigil by her casket in Kensington Palace the night before the funeral. The nurses in the hospital in Paris had given him a bundle of the clothes she had died in. Her great friend Susie Kassem, a magistrate, told me, "Her white jeans had turned black with her blood. At first Paul put the package in the refrigerator at Kensington Palace. Then he burned the clothes." She added, "He wasn't just a butler. He was her eyes, ears, her protector in life and in death, and he's paying the price for her.... Diana said to me, 'Apart from my sons, the only man I trust is Paul.' Look at the responsibility that puts on Paul."

The idea that Burrell would steal things from Diana seemed alien to his character. She was the most famous woman in the world, and he was probably in love with her in some obsessive way. That she could be difficult at times became more and more apparent, and he doubtless bore the brunt of her anger and frustration, but his devotion never flagged, or never for long. "She needs me," he said to one person I know who asked him why he stayed. "She has no one." I spoke on the phone to another of Diana's closest friends, Lucia Flecha de Lima, the wife of the former Brazilian ambassador to London, Paulo Tarso, just as she was leaving for Sao Paulo to fly to England "to hug Paul." She told me, "On the first Christmas, when the boys were at Sandringham with the royal family, she was alone. Then she announced, 'I'm going to Althorp [the Spencer-family home, where she had grown up] for Christmas.' The very next day, Boxing Day, a family day, she arrived at the Brazilian Embassy in tears. She said it had been the most horrible Christmas of her life. She said, 'My family told me I was disgracing them and ruining their lives.' She only trusted Paul. She didn't trust her mother. She wasn't sending her old clothes to her sister Sarah anymore. She thought Sarah was envious of her and wouldn't say thank you. It was a huge surprise for me to hear that they were the executors of her will. Diana was young. She didn't expect to die, but she once said to me, 'I'm sure if something happens to me they'll destroy all my papers.' She stored a box of letters and documents at the Brazilian Embassy for two years. I never looked at what was there."

I must confess to being predisposed to favor Burrell in this trial before I ever entered the courtroom. I had once had the extraordinary experience of speaking in depth with Princess Diana, and I was utterly captivated by her charm, her beauty, and her star power. It happened during a three-day break from the O. J. Simpson trial in Los Angeles, when I flew to London to attend a Vanity Fair party at the Serpentine Gallery, where she was the honored guest. When I was introduced to her, she put out her hand and said in the friendliest manner, "Don't tell me they've let you out of that trial." She had been following the Simpson trial on Sky television, and she wanted to talk about it, as so many people did during that period. "He's going to be acquitted," she said to me with a confirming gesture of her hand.

I said, "Oh, no, Ma'am," but indeed she turned out to be right. That night, the adjective I used in my journal to describe her was "awesome." So I was all for the butler she had called her rock.

Burrell and I spoke to each other in the cafeteria of the Old Bailey on the first day of the trial. I was feeling slightly shy, not knowing anyone in the media there yet, and was looking for a place to sit. As I walked by his table, where he was having lunch with his wife and brother, our eyes met. He rose from his seat, I put my tray down on a table, and we shook hands. I said something like "This has to be the most terrible ordeal for you." And he replied, "I never thought anything so terrible could happen to me." I wished him luck and told him I was rooting for him, and he thanked me. After that, we spoke briefly every morning in the corridor before entering the courtroom. He was clearly tense and nervous, but he was also polite and friendly. One day he said, "Happy birthday, one day late." I replied, "How in the world did you know it was my birthday?" I'm at an age where I don't go around announcing my birthdays. He simply said, "Oh, I know." Then, at his moment of triumph, after unexpectedly and abruptly being acquitted of all charges through the 11th-hour intervention of the Queen, he left the courtroom surrounded by policemen, lawyers, and reporters. When he saw me observing the scene, he broke away and walked over to me. He had just been sobbing in the courtroom, with his head on the shoulder of his attorney Lord Carlile, and he still had tears in his eyes. He put out his hand and said, "Thank you for believing in me." I said, "I'm thrilled for you, Paul." Then he made his way down the stairs of the Old Bailey and out onto the street to the cheers of the crowd that had gathered there. He said quite gallantly to one reporter, "You know, I've always had admiration, trust, and respect for Her Majesty. The Queen came through for me."

He went on to a celebratory lunch at Luigi's, one of Diana's favorite restaurants, with his lawyers and Susie Kassem. Within 72 hours of Burrell's acquittal, however, his love and devotion came into serious question. In three words, he blew it. Public opinion promptly turned against him when it was announced that he had made a deal with The Mirror, an English tabloid, to tell his story for £300,000, or $480,000.

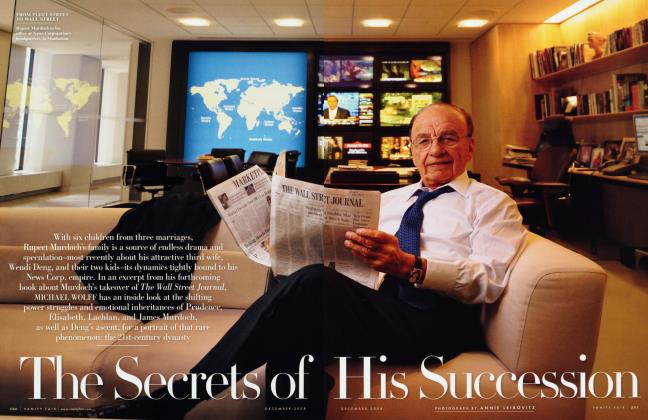

Then, in a startling example of dirty one-upmanship, a rival tabloid, the News of the World, owned by Rupert Murdoch, who is known to be hostile to the monarchy, pulled the rug out from under The Mirror by printing a leaked copy of a highly confidential deposition made with Burrell's cooperation to document his closeness to the Princess. Who actually leaked the report to the News of the World is unknown, although a public-relations person Burrell had passed over in favor of another was suspected of being the culprit. In this statement, which was never meant to be made public, Burrell told how he would deliver Diana's lovers to Kensington Palace at night in the trunk of his car so that the palace guards would not see them. He told how she once came out naked under a fur coat and jewels to meet a Pakistani heart surgeon with whom she was besotted. Burrell's statement also revealed Diana's interest in common prostitutes and related how she would give them money and tell them to go home and get out of the cold. It has been rumored that Prince Philip called Diana a "harlot" and a "trollop" in angry letters to her, and that is exactly what the deposition made her sound like. Overnight, people who had stood loyally behind Burrell throughout the ordeal of his arrest and trial turned on him and called him a traitor. Richard Kay, the reporter from the Daily Mail who had been the Princess's most trusted confidant in the British press and who had made Burrell godfather of his elder daughter, told me, "He has been so dishonest. All of us who were going to take the stand for him are horrified."

Burrell's trial was jinxed from day three, when Mrs. Justice Rafferty dismissed the first jury. Things were made worse when the reporters were told not to reveal the reason for the dissolution of the jury; making a mystery only created endless speculation. The British system of jury selection is very different from our own, which in high-profile trials can take weeks while jury consultants whisper in the ears of attorneys to eliminate this individual or that one. The Brits pick a jury in about an hour. In this case the pool of jurors was asked only if they knew anyone who worked or had worked in any of the royal households. People who wanted to be excused had to explain their reasons to Mrs. Justice Rafferty. Some she let go, some she kept. In the British system there are no alternate jurors to fall back on, but a trial can proceed if one or two jurors drop out. On the third day of the Burrell trial, however, the judge decided to dismiss the entire jury. The second jury was picked in less than an hour, and the trial began again as the prosecutor, William Boyce, read aloud a list of 300 objects belonging to Diana which the police had found in Paul Burrell's house in Farndon, near Cheshire.

It is impossible for the average person to understand the complex relationship the royals have with their servants. The denizens of palaces live at such a rarefied level of existence that they see and trust few people in their private hours, when they are not performing their official duties of greeting dignitaries and attending functions in tiaras and diamonds. Their fear of betrayal is constant, and the Windsor-family members do not seem to enjoy even one another's society, although the Queen was known to be close to her late mother and sister. Often the only people they can totally relax with are trusted valets, maids, and butlers who have been in their service for years. There's a famous story, probably apocryphal, about the late Queen Mother Elizabeth, who was known to like her gin. One night, H.R.H. supposedly rang downstairs to her butler and footman and said, "Will one of you old queens bring this old Queen another gin-and-tonic." That was an amusing thing for an old lady to say, but it also shows the easy, open relationship she had with her servants. In retrospect, Diana became far too close to Paul Burrell. He knew enough about her to sink her, and the outcome of his trial has resulted in a deplorable sullying of her name five years after her death.

Prince Charles is also known to be extremely loyal to his servants, who number 85, according to outraged reports in the English press. He has shown particular favor toward one of his closest aides, whose legal bills in the matter of the alleged rape of another palace staffer have been paid by the Prince to the tune of £100,000. Michael Fawcett, his personal assistant, is being investigated for fencing up to £100,000 a year in unwanted gifts for the Prince. Because palace servants are underpaid, they are often rewarded with gifts the royals have been given or clothes they no longer wear. Someone in the service of the Prince of Wales told me about a rarely used dining room in St. James's Palace, which has been Charles's home since his divorce. When the Prince entertains with Camilla Parker Bowles, they have small groups and dine in smaller rooms. The dining table in the large dining room, which seats 40, is covered with gifts that have been sent to the Prince from foreign leaders or presented to him during public appearances. I was told that once, walking through that room, the Prince said to an employee, "Oh, take anything you want." That same person told me that the small apartments in town and cottages in the country occupied by royal servants are often furnished like small rooms in one of the palaces, with bounty they have been given by grateful royals.

Speaking of royals, I had an extraordinary encounter in a revolving door at Claridge's a few days after I arrived in London. I was 15 minutes late for dinner at Green's restaurant on Duke Street with Simon Parker Bowles, who owns the restaurant, and my old friend John Bowes-Lyon, who was related to the late Queen Mother. I try to be an on-time sort of person, so I was rushing. I ran through the lobby, went much too fast through the revolving door, and came within an eighth of an inch of colliding with a woman who was entering from outside. I found myself looking directly into the startled face of the Queen of Spain. I did all the right things. I called her Your Majesty. I bowed my head the way you do to members of royal families. I also apologized for my thoughtlessness in racing through the door. She could not have been nicer or more gracious. She shook my hand. I introduced myself. We had an eye-to-eye moment and went our separate ways.

For me, in hindsight, it is inconceivable that the Burrell case ever got to trial. In the simplest terms, it is like your cleaning lady nicking a few things she thinks you're not going to notice. It goes with the territory. You don't call the police. A murder has not taken place. You sit down and talk about it. But the Windsors and Spencers, who go back in history together, utterly despise each other because of Diana. It is clear that she was toxic to both of these families. However, the fact that no go-between tried to reason with them and persuade them to dismiss this case wound up doing all concerned great harm. The perfect person for that role, according to someone close to the royal family, would have been the Bishop of London, who was friendly with both Princess Diana and Prince Charles and who confirmed Prince William. In addition, he was an executor of Diana's will, although he had been left in the dark when her mother and sister, in their roles as executors, ignored Diana's bequest of a quarter of her "personal chattels" to her 17 godchildren, with the other three-quarters going to her sons. Since Diana left an estate of £21 million, each godchild could have expected to receive in the vicinity of £300,000. However, the legal definition of chattels is debatable, and Mrs. Shand Kydd and Lady Sarah McCorquodale instead sent keepsakes—like the odd bit of china—to the godchildren. Rosa Monckton, a close friend of Diana's whose daughter, Domenica, was one of the Princess's godchildren, was understandably irked when she received what she described in an irate article in The Sunday Telegraph as a tatty brown box with Herend china wrapped in newspaper inside, together with a receipt for her signature.

Burrell, the ever present butler, knew all the ugly secrets of Diana's relationships with her family—bad with her mother, bad with her brother, bad with one sister, and not great with the other. They had all let her down. In life she had been a public embarrassment to them, but they moved with record speed to commemorate her in death, making her grave at Althorp a paid tourist attraction, although she had been turned down by her brother when, after her separation from the Prince of Wales, she had asked for one of the cottages on the estate as a place to take her kids when they were not in school. She had already picked out fabrics and rugs when he told her no. They never spoke again. Her mother admitted on the stand that she hadn't spoken to Diana for four months before she died—according to Burrell it was six, and I believe him. At the funeral in Westminster Abbey, Lord Spencer delivered his blistering eulogy of pent-up rage against the Windsors for the treatment of his sister while the royals just sat there, on worldwide television, and showed no reaction. Back at the palace, however, there was fury, and the fury on both sides has grown through the years. One of my royal sources told me that even William and Harry have nothing to do with their mother's family.

In Kensington Palace after Diana's death, Paul Burrell, the keeper of the flame, was so horrified to see Mrs. Shand Kydd and Lady Sarah McCorquodale stuffing the Princess's letters into a shredder that he went to the Queen, whom he had served as a footman for 10 years, and told her he was taking some of Diana's things to his house for safekeeping. Five years later, that meeting between him and the Queen, who was known to be fond of him, would suddenly take on great meaning. In the back of the family Bentley, on their way to St. Paul's Cathedral to a memorial service for the victims of the terrorist attack in Bali, the 81-year-old Prince Philip said to his 54-year-old son, Prince Charles, "It's a bit tricky for Mummy because she saw Paul, you know." Spokespeople for the Queen later explained that she had been unaware that the prosecution's case was built on the premise that Burrell had taken the property and never told anyone about it.

He had, of course, told someone, and that someone was the Queen.

This shook Prince Charles into action. After the memorial service, he called his secretary, Michael Peat, and told him to phone his lawyer, Fiona Shackleton, and have her phone the police and the prosecutors—calls that would bring the trial to a screeching halt the day before Burrell was to take the stand. Burrell knew everything there was to know about the royal family, and he was facing seven years in prison for theft. Loyalty goes just so far when prison is staring you in the face. He was sure to talk. How could the Windsors and the Spencers not have realized that the greatest victims of this farcical trial would be the Princes William and Harry?

I have my own little role in this story. On my second day in London, an English friend who is close to the Prince of Wales read in a gossip column that I was covering the trial and staying at Claridge's. He called me and made a date for lunch. I have known him for roughly 35 years, but we rarely see each other. I told him I couldn't get him into the Old Bailey cafeteria, because you had to have a press badge to get into the building, but I could meet him outside. There were photographers flanking the front entrance of the courthouse all day, so I met my friend on a street corner a block away, and we walked to a restaurant. My friend, who shall remain nameless, moves in royal circles and has the highest sort of connections. After we got caught up on our families, we started to talk about the case. I said, "How could they have let it get this far?" He told me that the hatred of the two families knew no limits. He also told me two interesting stories.

First, he said that a secret meeting between Burrell and Prince Charles had been arranged sometime in the past, at which Charles was going to ask him to give back the objects the police had found in his house, and Burrell probably would have, because he too must have known what could come out in a trial. In order to ensure secrecy, I learned from another source, a house in the country had been borrowed for the meeting. The mistress of the house and the servants were to be away, and the Prince and the butler were to arrive at different times to avoid detection. That morning, however, the Prince played polo, took a nasty fall, was knocked unconscious, swallowed his tongue, and was put in the hospital. So the meeting between the two that could have straightened things out didn't take place, and it was never rescheduled. Soon the Prince cooled on the idea of a meeting. The police had convinced him that there was a photograph of Paul Burrell wearing one of Princess Diana's evening dresses, and that Burrell had been secretly selling her things. Both of these accusations were false. There was no such picture, and the reason Burrell had money in his bank account after Diana's death was that he had written a best-selling coffee-table book called Entertaining with Style, in which he explained how to eat a banana with a knife, how to fold a napkin properly, and what the distance between forks should be in a place setting for a dinner party. In addition he had become a popular figure on the lecture circuit.

My friend also told me that Burrell had earlier been to see the Queen, information he had heard right from the Queen's lips. He told me, "The Queen is best late at night, after 11, when the phones have stopped and she has had a few drinks and is relaxed. She enjoys talking. That's when she told me that she had seen Burrell. She said that the royal family couldn't interfere with the court of law." At that time, I did not get the full significance of what he was saying.

A few nights later, I was at a dinner in a private upstairs room at a restaurant with several journalists, including Richard Kay. Without mentioning my friend's name, I said, "Burrell went to see the Queen after Diana's death." I was assured by several people that that simply was not true, although, as we were to find out in due time, it was.

After Burrell's case was dismissed, I went on several television shows, and the BBC taped me for an evening radio broadcast. On that show, which I have not heard, I apparently said that I had known of the meeting between the butler and the Queen for several weeks. I said that I couldn't understand how it was that I, an American, could know such a thing when key people in the case did not.

As Prince Charles and Camilla Parker Bowles were driving to an estate—not their own—for a hunting weekend, they heard me on their car radio saying that I knew Burrell had been to see the Queen. Prince Charles called one of his public-relations people and said, "How come Dominick Dunne knows Burrell went to see my mother? Camilla says you know him. Find out who told him." That person came to see me for lunch in the Reading Room at Claridge's the next day, and Richard Kay joined us. We talked about the case, point by point. Kay expressed some worry that Burrell, for whom he had been prepared to take the stand, might be making serious mistakes in dealing with his representation in forthcoming matters of television and book offers, which had begun to pour in. After Kay left, my other guest said that Prince Charles wanted to know who had told me that Burrell had been to see the Queen. Naturally, I didn't tell. I never tell those things under any circumstances. In any case, it would soon develop, the Prince had much more serious things to worry about. So did his mother. The monarchy was in crisis again.

When the police, spurred on by the Spencers, brought charges against Paul Burrell for theft of properties belonging to Princess Diana, Prince Charles, and Prince William, they could have had no idea of the possible consequences of their inadequate case, including the exposure of the alleged gay rape of a young valet named George Smith by one of Prince Charles's most trusted manservants. Smith was a friend of Burrell's, and several years later Burrell told the story to Princess Diana. Smith was then in the hospital for stress and rehab, and Diana went to visit him. One of the things that made her the people's princess was her habit of visiting the sick and disabled and bringing them joy and comfort. It's the next part of this story that I find so indicative of Diana's complex nature. Apparently Smith poured out his story to her, but what he didn't know was that Diana was secretly taping him the whole time. That gay-rape tape would become the focus of the media in the days following the termination of Burrell's trial. Diana had kept the tape in a wooden box with the initial D on it, along with several letters, which are said to be churlish in the extreme, from Prince Philip, her former father-in-law. If so, the publication of those letters would be an abomination for the Queen, particularly as she comes to the end of her grand Jubilee year.

The third thing in the box was a piece of jewelry, which the prosecution made a great mystery about, saying the subject was too sensitive to be mentioned aloud and had to be written on a piece of paper by the police witness on the stand and handed to the judge, who would not tell Lord Carlile anything except that it was small. It turned out to be a signet ring belonging to James Hewitt, the man known as "the love rat" because he had written a detailed book about his five-year love affair with Princess Diana, which caused acute embarrassment to many individuals and was thought of as a betrayal by Diana. (The very night the ring was introduced in court, I was having dinner with my friend Afdera Fonda, the fourth wife of Henry Fonda, and a group of friends at Riccardo's on the Fulham Road, and there, two tables over, was the love rat himself, pouring wine for two fabulous-looking ladies and a couple. You'd never have known there had been all this sensitive talk about the signet ring he had given the Princess.)

The rape tape, which was in the box, is missing. As I was saying good-bye to my new British media friends, one of them said, "You wait. The rape tape is going to become the story." I think he's right. Already, we have been told in the English papers that Prince Charles paid £38,000 to George Smith, the alleged victim in the rape, who has left royal service. No wonder the Queen had a sudden memory revival the day before Burrell was to take the stand.

Something about this story still doesn't hang together. It seems to me that if the Queen and her son and heir ever have chats together, they would have certainly gotten around to the potential consequences of the Burrell case before it was too late. If you look at photographs of the Queen, Prince Philip, and Prince Charles in the back of their Bentley on their way to the Bali memorial service, they appear to be three of the unhappiest people imaginable, none of them talking, all of them in their private worlds of troubled thoughts. If we are to believe what they tell us, that the Queen finally told Charles about her meeting with Burrell five years earlier, then must not Charles have made known to his mother the existence of the rape tape, and isn't that why they went into action?

If the Burrell case did nothing else, it probably ended the fantasy held by Mohamed Al Fayed, the controversial owner of Harrods, that his son, Dodi, and Princess Diana were one of the world's great love stories. Diana's relationship with Dodi lasted only six weeks, and they spent a grand total of 32 days together. She told Burrell that she thought he had a cocaine problem, because he went to the bathroom so often and always locked the door. As I was leaving London, Mohamed Al Fayed threatened to sue Burrell for saying that Dodi was a cocaine addict, but I would bet that he will not pursue such a suit. Far more interesting was Burrell's revelation in The Mirror that the Queen had told him, "No one, Paul, has been as close to a member of my family as you have. There are powers at work in this country which we have no knowledge about." We have only Burrell's word that the Queen made the statement, but Mohamed Al Fayed has pounced on it. He has often said that Diana and Dodi were assassinated, and has accused Prince Philip of being the principal figure behind their deaths. He recently went on television to say that the Queen's statement bolstered his belief that Diana and Dodi were murdered in the tunnel in Paris.

As I write this in my New York apartment, Paul Burrell is also in Manhattan, being famous and lining up a fortune. He is here with his wife and two sons, who used to be playmates of Prince William and Prince Harry's, when their father was Princess Diana's butler and their mother was her dresser. The press is following them everywhere, even as the English papers are circulating backstairs gossip of a prurient nature, most of it gay. Burrell himself is not exempt. His wife says she knew everything when she married him. I tried to call Burrell at the Millennium hotel, where he is staying, but the operator said no person was registered there under that name. Then I watched him on television, surrounded by cameras, walking on the street and making a statement but refusing to answer questions. He did say that he was shocked by the falsehoods that were being said about him, especially by people who used to be his friends in the media. His eyes looked dead to me. It seemed as if he was beginning to understand the consequences of selling your soul for money.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now