Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowAfter firing a final, well-deserved shot into the corpse of Gary Condit’s political career, the author turns to the latest gossip from the Michael Skakel murder trial, a little dustup with the great Elizabeth Taylor, and—what diarist would miss it?—the scene at Liza’s wedding

May 2002 Dominick Dunne Michael O'NeillAfter firing a final, well-deserved shot into the corpse of Gary Condit’s political career, the author turns to the latest gossip from the Michael Skakel murder trial, a little dustup with the great Elizabeth Taylor, and—what diarist would miss it?—the scene at Liza’s wedding

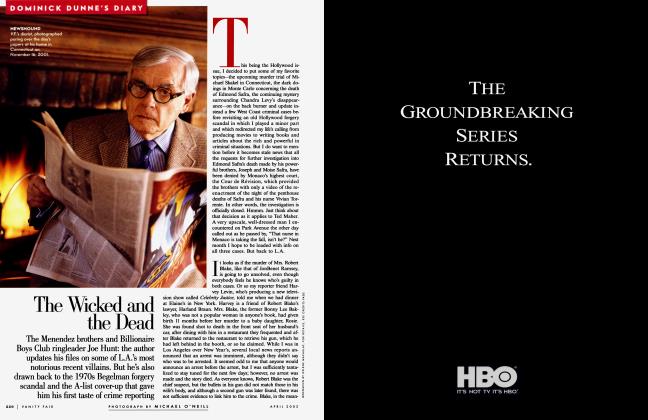

May 2002 Dominick Dunne Michael O'NeillNext January the 30-year political career of Congressman Gary Condit, of the 18th District of California, will come to an abrupt halt, and hopefully be over forever, to the huzzahs of many, including me. His blatant public lack of interest in the welfare of his discarded mistress, Chandra Levy, after her mysterious disappearance almost one year ago brought him the sort of fame that 11 years in Congress never had. It is difficult not to remember Condit at the time of the disappearance, smiling and walking jauntily past the battery of television cameras and shouting reporters, with his suit jacket slung casually over his shoulder, acting more like a man attending a film premiere than one whose lover had recently vanished without a trace. It was the beginning of the fame that would ultimately destroy him in a staggering defeat in the Democratic primary on March 5.

Shortly before the primary, Condit was interviewed by Frank Bruni in The New York Times Magazine, and he had the chutzpah to make a campaign pitch by saying, “I may be the best hope [the parents of Chandra] have to keep the issue alive. Somebody else gets elected— you probably won’t hear much about Chandra.” Such a lack of grace, I thought, considering his evasiveness on the several occasions when he had the opportunity to make a statement on the subject on television to a public eager to know what he knew.

My biggest moment of the past month was when Gary Condit dissed me on Larry King Live. He scolded Larry for having me as a guest on his program. He said, “You let him come on here and make up stuff.” I can’t tell you how much I enjoyed watching that. Obviously, I had gotten to him. Yes, before September 11, I had divulged the theory on Larry King’s show that Chandra may have disappeared on the back of a motorcycle driven by one of Condit’s biker pals in the Hell’s Angels. The story virtually vanished after that date. I had also said several months later on the show that a procurer of women for the nocturnal pleasures of Middle Eastern potentates and their ambassadors in Washington had told a horse whisperer in Dubai that my motorcycle theory, which he had seen me explain on the earlier Larry King show, was incorrect, because he had been in Washington at the time—delivering girls, I presume—and claimed to know that Chandra had been kidnapped, put in a limousine, drugged, and placed on a private jet.

Condit said early in his hour-long interview with King that he wasn’t going to discuss Chandra Levy. Certainly no one tuned in to that interview to hear about water rights in the 18th District of the state of California. I wanted a little light shed on Chandra’s disappearance, or a few details about the last time Condit was with her, or something, but that was not to be. Whether it was intentional rudeness or mere sloppiness, Condit twice referred to Dr. Levy, Chandra’s father, as Mr. Levy. He blamed the media for the bad publicity he had received, not allowing for a minute that he had created the atmosphere of distrust that mushroomed around him. He told the sad story of the mother of another missing person, who couldn’t get any attention paid to her child’s disappearance. If that poor mother’s child had been romantically involved with a congressman right up until the disappearance, she certainly would have gotten publicity, but Condit didn’t make that logical step.

There was a disturbing item on “Page Six” of the New York Post on February 19, describing a sexual scene of startling depravity—with an audience involved—in which Condit was the central figure. The Post credited the San Francisco Examiner with the story. I won’t go into the details here, tempted though I am, except to say that his body was reportedly entirely shaved for the orgy. Let’s, for the sake of argument, say that the story was totally false, that he had never been part of such an orgy, wearing the leather outfit the paper said he had worn. It is a sign of the smarmy public feeling he has created that such degrading stories continue to cling to him. To give the congressman his due, he was gracious in defeat. I firmly believe that one of these days the truth is going to come out about Chandra Levy.

Gloria Vanderbilt and I went to the stately mansion of Woody and Soon-Yi Allen, who were having a dinner party in their stunning new digs on the Upper East Side. It’s the kind of house a Vanderbilt might have lived in during the years of their glory. Woody played the docent, taking us from room to room, pointing out the magnificent winding stairway he had had installed, but Soon-Yi was the lady of the manor, calmly rearranging place cards when there was a last-minute no-show, indicating to the butler when it was time to serve, and leading us into the living room for coffee. When Woody talks, you don’t want to miss a word. Gloria and I had a great time.

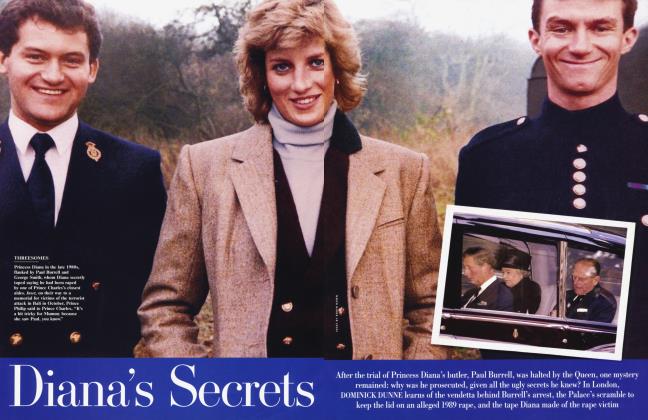

I was sad to hear of the death of Princess Margaret. She was the Princess Diana of her time, a description she would probably hate, for she shared her family’s disapproval of the late Princess of Wales. Once, at a lunch party at the vacation house of Prince Rupert Loewenstein, the business manager of the Rolling Stones, in the Hollywood Hills of California, I heard her say in reference to Diana, “The only one who’s behaved properly in this whole mess is Camilla Parker-Bowles.” Like Diana, Margaret was a public figure whose private emotions were laid bare for all the world to see as she carried out her royal duties in tiaras and jewels, photographed almost every day of her life. She loved a man her family would not allow her to marry. She married another man, had two children, went through a divorce, and had occasional inappropriate liaisons—all written about. She could be difficult and snobbish, but she could also be witty and entertaining. She knew the lyrics of practically every show tune of the musical theater. I remember a weekend at the Arizona ranch of a former ambassador to the Court of St. James’s, the late Lewis Douglas—whose daughter, Sharman, was for years a close friend of the princess’s—when she performed like a nightclub singer, with a microphone in her hand, moving about among the guests, completely enjoying herself. She was plagued by ill health in her last years and dropped out of the public eye. There was one tragic photograph of her, looking old and unrecognizable in a wheelchair, all glamour gone. Her son and daughter were a credit and comfort to her. Despite her being the only sibling of the Queen of England, her death barely made the news in this country. The Queen went right on with her duties, which included conferring a knighthood on former New York mayor Rudolph Giuliani. The funeral at Windsor Castle was private, attended by a few hundred invited friends. If it was even on the evening news in this country, I must have missed it.

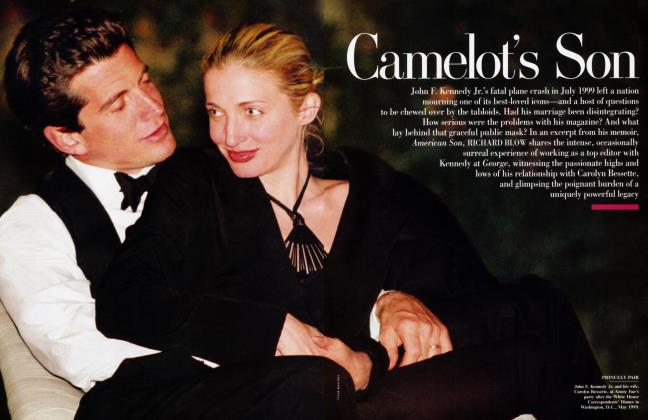

By the time you read this, the long-time-coming trial of Michael Skakel for the brutal murder of Martha Moxley in 1975 will be under way, but before it begins the defense team is using the media to create doubts, which is what it is expected to do. There was a plant in one of the New York tabloids and most of the papers in Connecticut, from where the jury will come, that a hair found at the crime scene has similarities to samples taken from Ken Littleton, the live-in tutor for some of the Skakel sons, whose first night on the job happened to be the night of the murder. Believe me, if Littleton could have been blamed for the murder of Martha Moxley, he would have been years ago, and the Skakels would not have had to endure the 27-year disgrace of being suspects.

Then came another bombshell, guaranteed to cause more than a ripple at the trial, which is to be held in Norwalk, Connecticut. As The Hartford Courant headlined on March 8, KENNEDYS WILL ATTEND SKAKEL TRIAL. Having once watched this legendary American family take over a courtroom, during the William Kennedy Smith rape trial in Palm Beach in 1991—with a priest in a Roman collar sitting among them during the closing arguments—may I say that they create a formidable sense of power. Priests in Roman collars are not held in high esteem these days, so that part will probably not be repeated, but Ethel Kennedy, the aunt of Michael Skakel, has, as the widow of a popular assassinated presidential candidate, achieved historical importance in our country, and she will surely outshine Dorthy Moxley, the mother of the victim, as the center of attention in the courtroom.

Actually, as I think about it, it is curious that Ethel Kennedy should plan to attend the trial. In 1998, before his arrest and indictment, Michael Skakel wrote a proposal for a book about his family called Dead Man Talking: A Kennedy Cousin Comes Clean, in which he was extremely critical of his Aunt Ethel in the matter of the death by drug overdose of her son David in the Brazilian Court hotel in Palm Beach in 1984. Skakel, who says he had been assigned the job of putting the desperate David Kennedy in a drug-rehab center on short notice, claimed that his aunt had forbidden him to use the Kennedy name to gain admission, and without using pull he had been unable to place David where he might have been helped. The proposal is also filled with dark stories about William Kennedy Smith, Robert Kennedy Jr., and especially the late Michael Kennedy, who was killed in a skiing accident in Aspen in 1997. I have heard through the grapevine that Richard Hoffman, the co-author of Skakel’s unpublished book, will be called as a witness. I have also heard that the young woman once known to the public only as the 15-year-old baby-sitter with whom Michael Kennedy had had an affair—an affair that broke up his marriage to Victoria Gifford, the daughter of Frank Gifford, the sports announcer—will be a witness. Allegedly, it was Michael Skakel who blew the whistle on the affair, after Michael Kennedy had fired him from his job at Citizens Energy Corporation, a nonprofit company that provides fuel and heating for the poor of Massachusetts. Robert Kennedy Jr. was quoted in The Hartford Courant as saying, “My mother, who joined the [Kennedy and Skakel] families together, never had any bitterness toward Michael [Skakel], She understands what he’s been through.”

Princess Margaret was the Princess Diana of her time.

Robert Kennedy Jr. told a reporter from USA Today that I led the lynch mob against his family. That’s not true. My specialty is writing about the rich and powerful in criminal situations, and his relatives have turned up as defendants in several cases I have covered. I make no bones about the fact that I am a strong advocate for victims—that’s the core of my trial reporting. When I met Dorthy Moxley in 1991, I swore to her that I would help her get justice for her daughter, even though the Skakels had been powerful enough to keep the murder on a back burner since 1975.

I’ve had a slight rift with Miss Elizabeth Taylor, the greatest I of movie stars, at least in my book, who has been a friend since I produced one of her films, Ash Wednesday, in Italy in 1973, when she was married to Richard Burton and they were the world’s most glamorous couple. She had just turned 40 and was at the peak of her amazing beauty. For a starfucker like me, spending the better part of a year in Cortina d’Ampezzo, a fancy winter resort in the Dolomite Mountains, with the Burtons, as they were called, and their considerable retinue, their 30 trunks, their Rolls-Royces and chartered jets, was the ultimate in surreal living. The movie didn’t turn out to be as good as the experience of witnessing the daily high-voltage drama that was their normal existence. I always meant to write about it and never did. Last month I got a telephone call from my old friend Michael Korda, the Simon & Schuster editor in chief, asking me to write the preface to an upcoming book called Elizabeth Taylor’s Jewels. Michael reminded me that Elizabeth still has one of the great jewel collections, and that pictures of them would be accompanied by Elizabeth’s stories of how she came to possess each of the beautiful pieces. I declined, pleading that I was very behind with my next novel, A Solo Act, that I was further committed to the monthly diary in this magazine and a new television show, and that there was just no time.

“Elizabeth said that you are friends,” said Michael.

“We are, but I don’t have the time.” That night I was talking on the phone to the playwright Mart Crowley, and he urged me to write the preface. “You could do it in an hour and a half,” he said. “You have such great stories about her, and you like her.”

So I called Michael Korda back and said that I would do it. It took a lot longer than an hour and a half. It took almost a weekend. But I enjoyed writing it, because I am fond of Elizabeth, although I rarely see her anymore. I thought the piece turned out to be funny and loving, even as it revealed a kind of life not many people have access to. Korda was pleased with it. “It’s very funny,” he said. Several people I read it to also enjoyed it. But Elizabeth apparently didn’t think it was funny at all. She suggested changes that would have removed every laugh in it. She said things hadn’t happened as I said they had, but I’ve kept a journal for 40 years, and I recorded the year I spent with Elizabeth and Richard in Cortina in great detail. I was furious with myself for having wasted so much time when I should have been working on the novel. Moreover, I certainly wasn’t about to take more time to do rewrites to suit the star, so I withdrew the preface and declined payment for my work. I am sorry if I upset Michael Korda, because I had written my first book for him, a terrible flop called The Winners. He provided the guiding light to my late-life writing career one day when he said to me, “There is nothing the public enjoys more than reading about the rich and powerful in a criminal situation.” Bells went off in my head, and found the niche I had long been looking for. Years later, when spoke to him about that line, he didn’t even remember saying it.

As Noël Coward wrote about one marvelous party, “I couldn’t have liked it more.” I’m saying the same about Liza Minnelli and David Gest’s wedding, which was the talk of New York for the week leading up to the nuptials. The crowds behind barricades at Marble Collegiate Church, where the ceremony took place, and the Regent Wall Street hotel, where the reception was held, were the size of crowds at Hollywood premieres. Everybody loves Liza for the ups and downs of her well-reported life, and her fans turned out in droves to let her know it. I’ve known Liza for years, though never well. Her mother, Judy Garland, once cleaned out my late wife’s medicine cabinet during a party at our Beverly Hills home, when she was married to her third husband, the producer Sid Luff. I knew Liza’s father, the director Vincente Minnelli, well, especially during his third and fourth marriages, when he was married to friends of mine. I went to Liza’s second wedding, to the late Jack Haley Jr., in 1974, given by Sammy Davis Jr. and his wife, Altovise, at the Comedy Store on Sunset Boulevard. Liza’s half-sister, Lorna Luff, who wrote a moving memoir of her family, Me and My Shadows, is a friend of mine. The sisters have an on-and-off relationship. Lorna did not attend Liza’s wedding, because she was performing in Australia.

Every woman in the wedding party was dressed in black.

Two nights before the wedding, I went to the bridal dinner, which was given by Liza’s former stepmother Mrs. Prentis Cobb Hale of San Francisco, at Le Cirque on Madison Avenue. There were 28 guests, including folks such as Clive Davis and Martha Stewart—a typically glamorous Denise Hale event. I hadn’t seen Liza for a year, since she had stopped by my place in Connecticut when she was house-hunting in the area. We went out to dinner with my neighbor Cynthia McFadden, who was doing a piece on Liza for ABC, and Sam Harris, a singer friend of Liza’s. She was then very overweight, slightly manic, and clearly unwell. Has she changed! She looked great at the bridal dinner. She was happy, funny, almost slender, not remotely manic. We were in the main dining room, and she was the center of attention for everyone in the restaurant. Liza is the kind of person total strangers root for. She said, “Dominick, you haven’t met David. You have to meet him.” Gest was at the far end of the long table. I went over and said, “Congratulations, David. I’m Dominick Dunne.” He replied, “Ann Rutherford sends her love.”

For people too young to remember, Ann Rutherford was Polly Benedict in the Andy Hardy series, which starred Mickey Rooney, way back when. She and Rooney were both at the wedding, because Liza invited all her mother’s friends from the MGM days, including Arlene Dahl and Ann Blyth. Janet Leigh, immortalized in a shower stall in Psycho, was there, as were Anne Jeffreys and June Haver, who was once a nun and who is the widow of Fred Mac Murray, a movie star of the 30s and 40s who made an extraordinary comeback on television in My Three Sons in the 60s.

The flowers in the church were the prettiest I’ve ever seen, thousands of white orchids cascading down from the pillars on gold wires. The ceremony was an hour late starting, and there was a certain sense of high camp. I said to the actress Marsha Hunt, who was sitting one over from me, “Maybe there’s been a last-minute change of plans.” It turned out not to have been the bride or groom who held up the works, but rather Elizabeth Taylor, the matron of honor, who had arrived in slippers and forgotten her shoes, which someone had to brave the St. Patrick’s Day parade outside and get from her hotel. She didn’t walk in the procession with the bridesmaids. Marisa Berenson, the second matron of honor, led her to a chair by the altar, where she sat throughout the ceremony. (She did not attend the reception.) This wedding was like a show in a church, with lots of applause and an inordinate amount of kissing, with tongues, at the altar, even before the minister said, “I now pronounce you man and wife.” At one point Gest kissed Liza romantically on her bare neck. She looked wonderful in her Bob Mackie white gown trimmed with pearls and brilliants. Michael Jackson, Gest’s best man, and Marisa Berenson took turns helping her with the train. Years ago in Beverly Hills, I was at Marisa’s wedding to a businessman named James Randall, which didn’t last, and Liza was her bridesmaid. Jane Withers, a child star when I was a kid, sat behind me in the church, wearing plenty of good diamonds but looking and talking exactly the way she had as a child. Margaret O’Brien, another former child star, was across the aisle. Marsha Hunt looked elegant and wonderful. “I went under contract to Warner’s in ... 1936, I think it was,” she said. “My career was ruined by the blacklist.”

When the ceremony started, Gina Lollobrigida, in a bouffant wig, was the first bridesmaid out, followed by the columnist Cindy Adams, Mia Farrow, and a dozen more well-known figures, all long past bridesmaid age. Every woman in the wedding party was dressed in black, a color not usually associated with weddings. The women had been told they could choose what to wear, but it had to be long and black.

Natalie Cole was an 11th-hour fill-in for Whitney Houston, who dropped out. Standing in front of the altar, she sang “Unforgettable” beautifully. During the ceremony, it was Liza, not Elizabeth Taylor or Michael Jackson, who dominated the scene. She got applause when she entered the church and again when she kissed the groom. As she walked out of the church, she stopped to hug people who caught her eye. The reception was wonderfully done. You realized how skillful David Gest must be at producing spectacles when you saw the effortless manner in which one musical act after another took the stage. Petula Clark sang “Downtown,” and the crowd went wild, as it did when the 5th Dimension sang “Up-Up and Away.” I left after midnight, and neither Liza nor Michael Jackson had yet taken the stage.

At one point, when I crossed the ballroom to go to the men’s room, a guard put his hands up and wouldn’t let me through, because I would have had to pass Michael Jackson’s table. The guard suggested an alternative route. Jackson was wearing a black outfit with a white Peter Pan collar, and an enormous diamond brooch with a pearl pendant at his throat. He was just sitting there, being more famous than anyone else.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now