Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

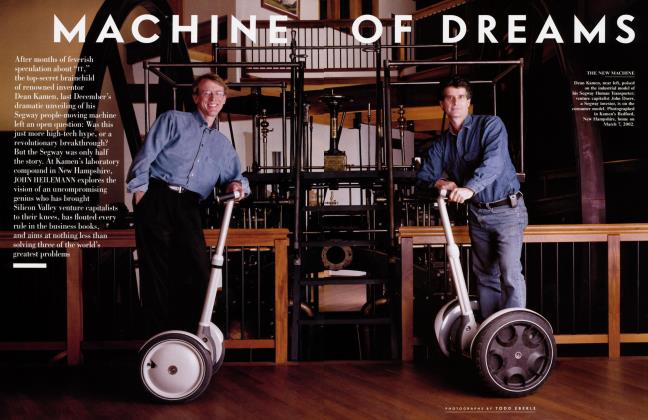

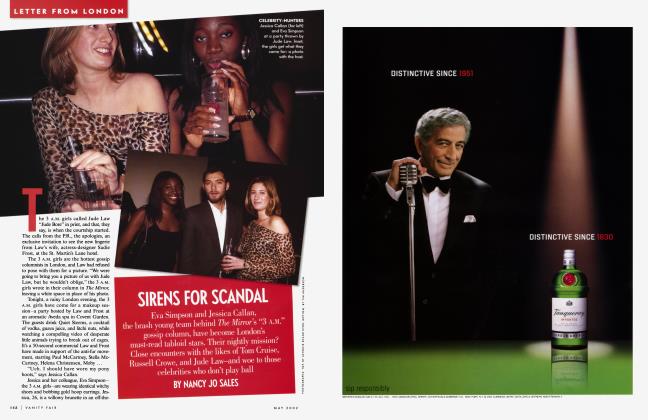

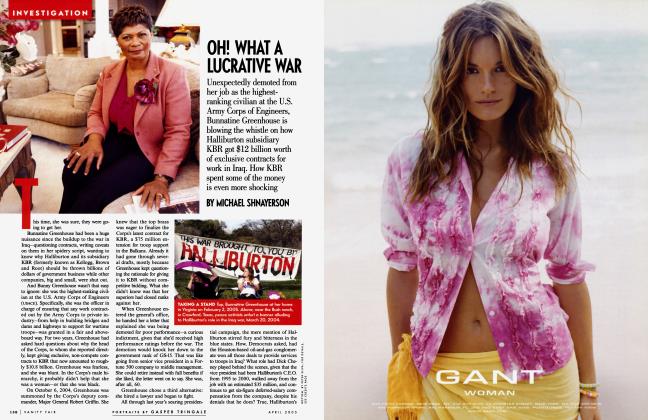

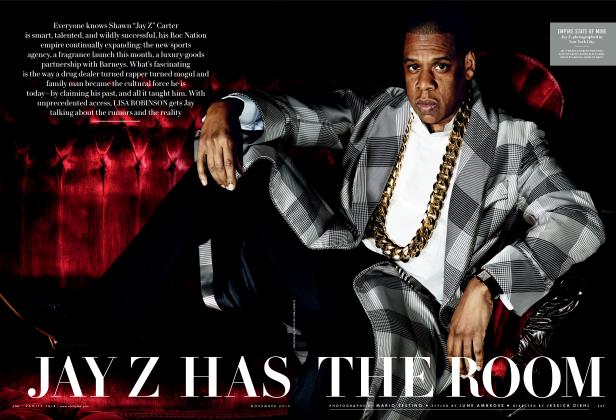

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowA teen idol since her 1994 breakthrough in Interview with the Vampire, Kirsten Dunst is making the transition to grown-up stardom with two very different roles: as sultry Marion Davies, opposite Edward Herrmann's William Randolph Hearst, in Peter Bogdanovich's The Cat's Meow, and as Mary Jane Watson, wide-eyed beloved of Tobey Maguire's Peter Parka, in Spider-Man. MICHAEL SHNAYERSON gets the 19-year-old actress to explain garbage-can bowling, her love of housework, and how she learned to upside-down kiss

May 2002 Michael Shnayerson Mario Testino Sarajane HoareA teen idol since her 1994 breakthrough in Interview with the Vampire, Kirsten Dunst is making the transition to grown-up stardom with two very different roles: as sultry Marion Davies, opposite Edward Herrmann's William Randolph Hearst, in Peter Bogdanovich's The Cat's Meow, and as Mary Jane Watson, wide-eyed beloved of Tobey Maguire's Peter Parka, in Spider-Man. MICHAEL SHNAYERSON gets the 19-year-old actress to explain garbage-can bowling, her love of housework, and how she learned to upside-down kiss

May 2002 Michael Shnayerson Mario Testino Sarajane HoareKirsten Dunst knows her life is about to change, and so do her security people.

“They told me I could make my house a ‘lockdown,’” she explains, all platinum-blond ringlets and wide blue eyes, as we stand surrounded by serpentine sofas and old industrial clocks at a Los Angeles furniture store called Blackman Cruz on La Cienaga Boulevard. “You put metal shades on the windows and doors, press a button, and—slam—they come down, and then no one can get in or out.” Dunst seems a bit awed at the thought. “I don’t know if I’ll do that, but after Spider-Man comes out, it could be a little scary.”

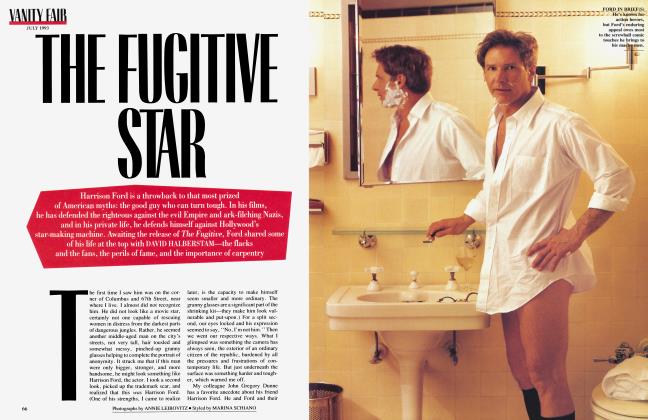

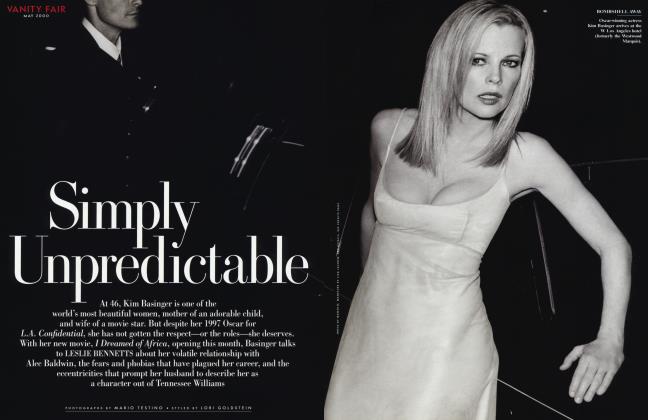

At the very least, passing as an ordinary 19-year-old Valley Girl will get harder when Spider-Man opens this month, with Tobey Maguire as Peter Parker (alias Spider-Man) and Dunst as Mary Jane Watson, the webslinger’s beloved girl next door. The dark horse of superheroes—younger and more vulnerable than Superman or Batman, and more likable too—is getting a big, splashy studio production from Columbia Pictures, which is sure to pump up the profiles of both young actors, but especially Dunst’s. Maguire is already the Dustin Hoffman of his generation, his sloe-eyed charm beautifully established in 1999’s The Cider House Rules and 2000’s Wonder Boys, not to mention The Ice Storm (1997). Dunst is an idol to the 12-to-17-year-old set for a string of fluffy teen movies, among them 2000’s surprise hit about rival cheerleader teams, Bring It On, but remains largely unknown to wider audiences.

For those who prefer films to flicks, Dunst has just opened in a nifty little period piece called The Cat’s Meow, in which she plays actress Marion Davies to Edward Herrmann’s William Randolph Hearst, aboard Hearst’s yacht in 1924. Her portrayal of Davies at age 27 is startlingly complex and beguiling: all flirting and fun in flapper’s beads and bangles, yet privately committed, in a poignant way, to the jealous newspaper magnate. In fact, The Cat’s Meow is just the latest of several small films that show Dunst taking well-chosen steps to make that most treacherous of passages, the one from teen actress to adult star, and doing it, so far, with all the grace and aplomb of one of her idols, Jodie Foster.

In real life, like many 19-year-olds, Dunst is part giggly girl, part ingenue. She’s stayed at home longer than a lot of teen actors, and when she’s there joshing around with her younger brother, her hair brushed straight and her figure knife-edge-thin, she seems about 14. Out and about, garbed in Marc Jacobs, with her hair done and makeup on, she seems a decade older. As for the house of her own—a rental, she quickly explains, and a cottage at that, but a first home of her own nonetheless—she hasn’t moved in yet, but she’s bought a white Philippe Starck sofa, and at the store on La Cienaga she pauses before an immense hanging cross. “Nope, I don’t think so,” she says cheerily. “I had enough of that at Notre Dame High School.”

The girl in Dunst can seem somewhat unformed, even about the movies. In her teen comedies she acts with the screwball charm of a Judy Holliday, yet she’s never seen a Judy Holliday film. A bit guiltily, she’s starting to watch classics, including, she says, that wartime one starring Burt Lancaster and Deborah Kerr with the scene “where they’re rolling around in the surf... From Here to the End of the Earth?" She waves a gorgeously elegant hand. “Or something like that.” Yet Dunst exhibits a quietly sturdy sense of herself. Like Foster, she’s acted since the age of three, first in television commercials, then in no fewer than 25 feature films, bit parts leading to larger ones, propelled by her breakthrough at age 11 as a young innocent turned ghoul in Interview with the Vampire. She knows the business and has an impressive depth of emotion to draw on—the upwelling of pure, unadulterated, natural talent. “Man, she can roll with anything,” says Peter Bogdanovich, who directed her in The Cat’s Meow. “She’s a pro.”

Bogdanovich, who knows a thing or two about talented young blonde actresses, admits that Dunst was the studio’s choice for Davies, not his own. He spoke to her on the phone from New York, and saw a video of Bring It On, but flew to Europe for the start of filming without having actually met her. “It’s called going with the flow,” he says wryly. He wondered if Dunst was too young for the part; he wondered if she could handle its sexual sophistication. At least, he thought, she has a period face.

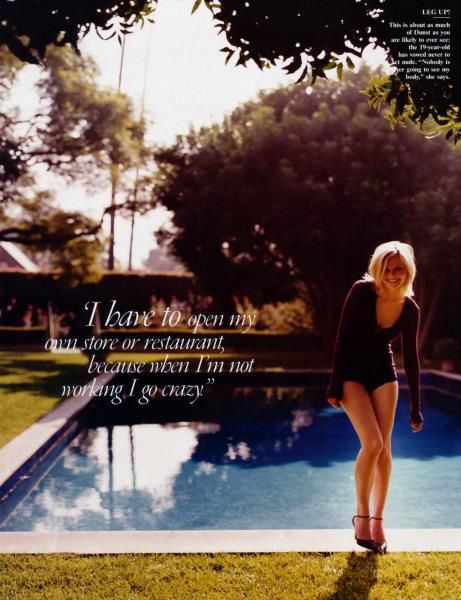

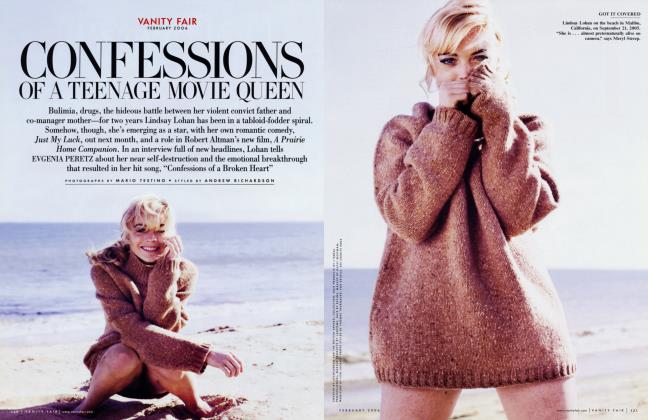

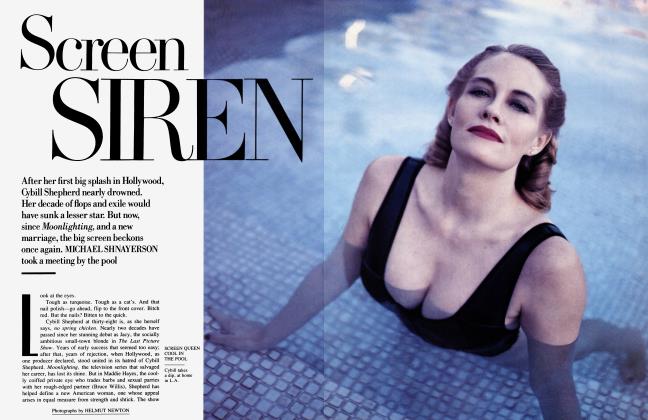

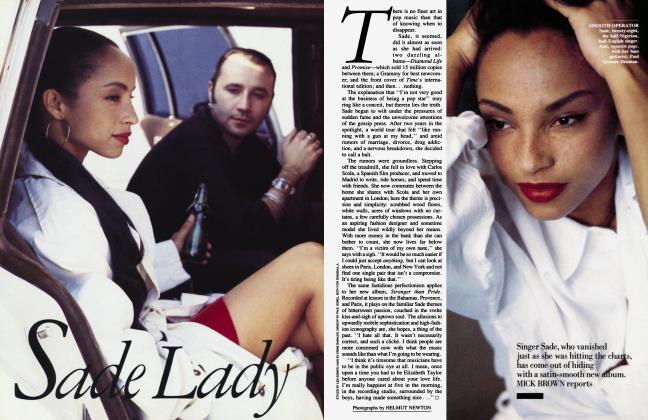

LEG UP! This is about as much of Dunst as you are likely to ever see: the 19-year-old has vowed never to act nude. “Nobody is ever going to see my body,” she says.

LEG UP! This is about as much of Dunst as you are likely to ever see: the 19-year-old has vowed never to act nude. “Nobody is ever going to see my body,” she says.

When Dunst arrived on set—perky but shy, with a boyfriend in tow to keep her company amid the adults—Bogdanovich regarded her with hope and trepidation. She could make or break a film the director had envisioned ever since he heard its story from Orson Welles in the early 1970s. Welles told him about a long-simmering Hollywood legend that Hearst had shot and killed silent-film maker Thomas H. Ince during a party trip aboard the press lord’s yacht, after mistaking Ince for fellow guest Charlie Chaplin, who Hearst believed was having an affair with his beloved young mistress, Davies. In fact, Ince did die after a trip on the yacht off the California coast; the cause, according to a medical report issued without autopsy, was acute indigestion. Aside from Chaplin’s chauffeur, who reported seeing Ince removed from the yacht on a stretcher with his head bandaged, no one on board ever publicly discussed the incident—including a young, ambitious columnist named Louella Parsons, who signed an unheard-of lifetime contract with Hearst newspapers soon after the trip.

In rehearsals, Bogdanovich began to relax. Eddie Izzard, playing Chaplin, improvised freely; Dunst, to the director’s delight, gave back as good as she got. Much of the script was rewritten in those first days. When filming began, Dunst was disconcerted by Bogdanovich’s penchant for long, one-shot scenes. There would be no “coverage”—other angles the editor could splice in later to cover mistakes. “But the actors who are any good come to love it, and want to do it with every scene,” Bogdanovich says, “Kirsten was like that.”

“I’m not sure she fully understood the fascination of a younger woman for someone significantly older,” muses 58-year-old Edward Herrmann, who plays the helplessly obsessed Hearst to perfection, “but she understood that Davies adored the guy, and so she threw herself into it with great enthusiasm, assimilating all the emotional dynamics of a more mature character. "I think she's an extraordinary girl. And I think she shows in this movie why she'll shortly become one of the best-known actresses we have on-screen.”

By the end of filming, Dunst had so inhabited her role that she could sit beside Herrmann, after the death of Ince, and in a long one-shot scene, without saying a word, convey a whole range of emotion—pity and tenderness for her older lover, mixed with guilt at her dalliance with Chaplin. “Orson [Welles] once said the camera photographs thought, not emotion,” Bogdanovich recalls, “and if you're thinking, the camera knows it. And, boy, was she thinking. It was like a gift.”

“At the beginning I don't think he really trusted me,” Dunst says. “He was always saying. ‘Lower your voice!’” And with his predilection for playing Pygmalion to young blonde actresses, Bogdanovich kept foisting books of film history on her—mostly his own. “But by the end,” Dunst says with shy pride, “he was asking me what my character should do.”

The film was shot in Berlin a lot of German money was in it—and it was there that Dunst got word that a desperate trio, the director, a producer, and the star of Spider-Man, would be flying over to audition her for a role she'd not even dreamed of getting.

Months earlier, after Dunst first heard that director Sam Raimi would be doing Spider-Man, she met with him in L.A. and thought they hit it off. While waiting in his office, she flipped through a comic book and decided she would be perfect for the role of Gwen Stacy, a character in the comic who was not even in the movie script. Months passed, and Dunst did not hear from Raimi. The role of Mary Jane Watson, though, went unfilled.

“We had seen a lot of great actresses,” Raimi explains. “They were believable and thrilling. But we were looking for the chemistry you see in all romantic pictures when they're working the chemistry that makes an audience want to see these two people together." None of those actresses clicked with Tobey Maguire the way Raimi thought they should. One month before the scheduled start of shooting, Raimi felt a cold vise of apprehension take hold in his chest.

That was when producer Laura Ziskin brought up Dunst again. “I mentioned her early on,” Ziskin recalls, “but [Sam] was so preoccupied with other things, he wasn't focused. So it wasn't 'Eureka!' But periodically I'd say, ‘What about Kirsten?'”

By the time Raimi agreed to read her. Dunst could audition only in Berlin and only after a full day of shooting The Cat’s Meow. From New York, Raimi and Ziskin called Maguire in Los Angeles to say that the three would have to fly over right away. Maguire had strep throat. "Sam,” he said, “you probably aren't even going to want to travel with me. I'm not saying I'm not going to go. I just want to talk it out.”

"Tobey,” the director said, “I'm leaving my kids and wife for the weekend. I'm making that sacrifice.”

"O.K., O.K.,” groaned Maguire, "don't say another word.”

When the trio checked in at their hotel in Berlin, there was a note for Maguire from Dunst, who had heard he was sick and wrote how much it meant to her that he'd traveled so far to see her. Maguire thought that was a pretty classy move, especially for a teenager. He'd seen Bring It On, and every day he was reminded of Dunst when he drove from his home past a huge image of her in a Gap ad on Sunset Boulevard. He'd figured Raimi must have called her earlier—she was such an obvious choice, he felt—so he hadn’t even mentioned her.

Dunst knocked on Raimi’s hotel door at the end of a day that had started at five A.M. She found the three inside with a video camera set up to shoot her right in the room. Maguire, still sick, looked miserable. Dunst could only imagine how poor the chemistry would be between them, but she did her best. She was so nervous that when the reading was over she left her CD case behind. But no one in the room looked the least bit displeased when she returned for it in acute embarrassment. “The moment she got in the room with Tobey,” Raimi recalls, “you saw it happen. They both just came to life.”

Raimi, a quirky director who started with cult horror films such as The Evil Dead (1982) and Army of Darkness (1993) and segued into the supernatural with 2000’s The Gift, had grown up loving Spider-Man and felt disinclined to mess with the icon that four decades of Marvel comics artists had portrayed. Not for him the dark personal phantasmagoria of director Tim Burton’s 1989 Batman. Raimi’s Spider-Man would be bright and fresh in its look, set in contemporary Manhattan, with duly bright and fresh young co-stars. But the director “tweaked” the backdrop with digital tricks. “There’s no building in our film that doesn’t exist in Manhattan,” he says. “There just wouldn’t be as many unique and fantastic buildings on one block.”

Against this backdrop, Maguire and Dunst (reborn as a redhead) enact a classic coming-of-age story, albeit one with a lot of spider-like jumping around and web-weaving aerial gymnastics. Spider-Man is an impetuous lad who has to learn how to use his powers wisely. He also has to find a way to get the girl he’s always loved—the girl who finds Peter Parker a bore; the girl he can’t date as Spider-Man either, because that would put her in danger. Mary Jane, for her part, has to realize she’s drawn to the wrong guys—the rich but shallow ones—and that Parker is the true love for her. Throughout the film, her only inkling that Parker may actually be Spider-Man is the result of a memorable moment that everyone on the set would refer to as the Upside-Down Kiss.

“He notices these two guys following me,” Dunst explains of Peter Parker. “They look like robbers. He quickly changes. Meanwhile, it starts to rain. They catch up with me, I’m starting to battle them off. And then Spider-Man appears—whisk, whisk—down his spider thread, and beats them up.” So quickly has Parker changed that his mask is not in place, so he whisks off, with Mary Jane crying, “Wait, wait!” Mask secured, he descends back into view, upside down, and the two share a kiss in the pouring rain that feels, for Mary Jane, oddly like a kiss Peter Parker plants on her lips not long after. “That,” says Laura Ziskin mischievously, “is when we said, ‘I wonder if there’s something going on between them.’”

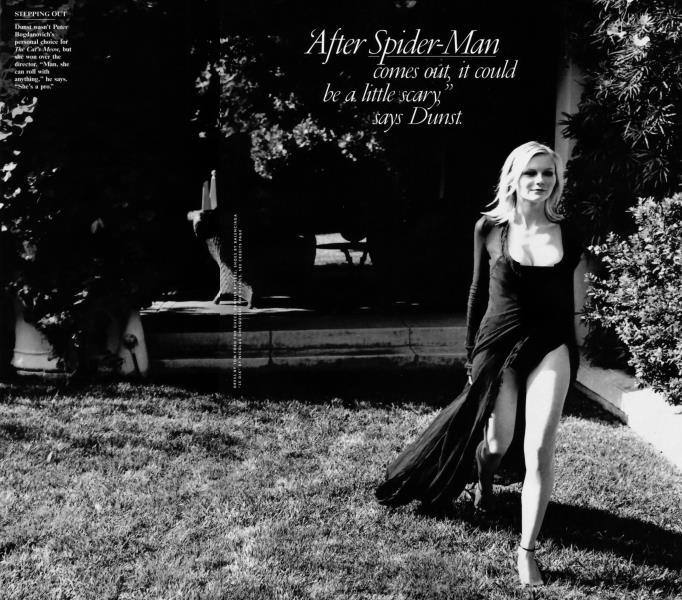

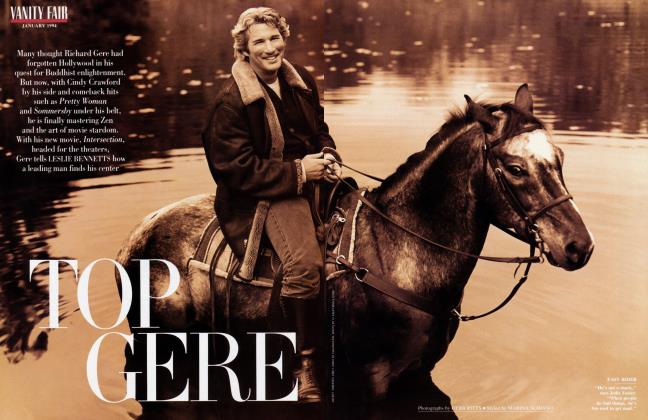

Dunst wasn't Peter Bogdanovich's personal choice for The Cut's Meow, but she won over the director. “Man, she can roll with anything," he says. “She's a pro.”

Dunst wasn't Peter Bogdanovich's personal choice for The Cut's Meow, but she won over the director. “Man, she can roll with anything," he says. “She's a pro.”

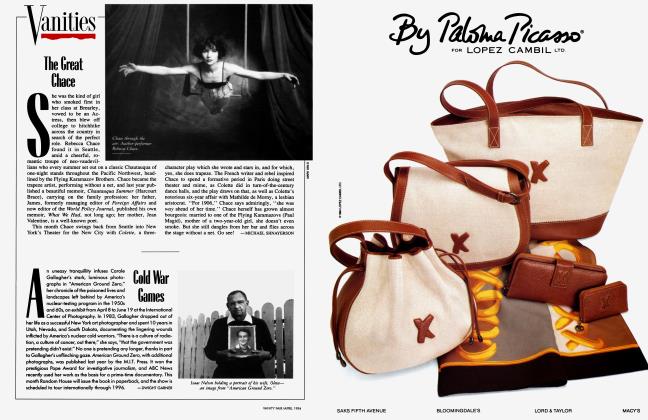

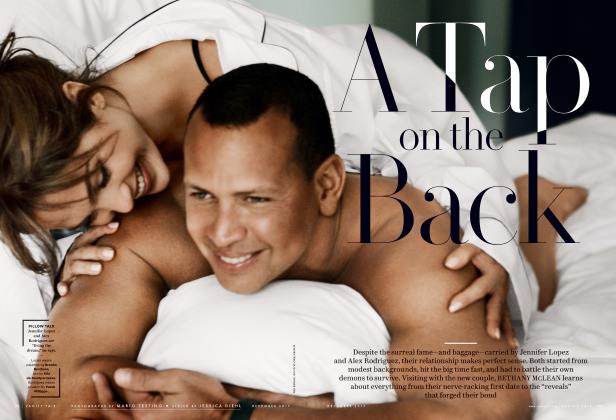

Despite tabloid rumors, Dunst says her co-star is just a friend, one she soon came to admire for his instant access to any emotion. “Tobey can cry just like that,” she marvels. “Whenever I have a crying scene, I have to listen to sad music, put my headphones on and kind of zone out.” Maguire found Dunst’s own emotional range amazing. “She’s very, very talented,” he says. “She’s very appealing and beautiful. She has a womanly quality, but also a very fun girl quality, an innocence. [And] there’s no vanity in her acting. She just commits and goes for it.” Also, Maguire says admiringly, “in the end, she had it tougher than me.”

The fact is that while Spider-Man has his share of aerial moments, thread-suspended in a hot, body-molded, spandex suit (“which he hated!” giggles Dunst), Mary Jane Watson is forever the damsel in distress. If Dunst wasn’t hanging off balconies, she was falling 80 feet in a hidden harness. (“They come to quite dramatic stops,” observes Raimi of actors put in such contraptions.) Jeff Habberstad, the movie’s stunt coordinator, confirms that Dunst did things that a lot of actors wouldn’t do. “There’s scenes where she’s falling off the Queensborough Bridge; in Times Square she falls off a 15-story balcony. In some of these shots, as a result, you actually see her falling quite a ways.” Dunst, says Habberstad, did it all without complaining. “She was a trouper,” says the gruff veteran of many a stunt fall himself. “And believe me, I wouldn't say it if it wasn’t true.”

Dunst says the scene that nearly broke her wasn’t a fall. It was a chilly, nightlong shoot for the upside-down-kiss scene in unremitting Hollywood rain. “It was January, freezing, and everyone else was in a warm coat,” Dunst recalls. “I was in a skimpy outfit with water up to my ankles.” A bit sheepishly, the director confirms this. “You can imagine what it’s like in a cold rain for an hour,” Raimi marvels. “But this was a 12-hour shoot! She’d be shivering uncontrollably between the takes. Then she’d muster the will and dispense with the shivers—and then deliver a performance as though she was perfectly warm.”

Raimi ended up as much a fan as Bogdanovich. “She has a complexity when you get the camera in close,” he says of Dunst. “She’s very intelligent, and there’s a lot going on behind the eyes.... I couldn’t even tell you what color they are. It’s about what’s coming from behind them.”

At the Dunst family’s Valley home, the door is likely to be opened by Kirsten’s mother, Inez, a big, garrulous woman who redefines the stage-mom type: passionate rather than hard-edged, proud rather than pushy. On one side of her is Kirsten’s twinkly-eyed and impish grandmother—Inez’s mom. On the other is happily obedient Kirsten.

All three generations of these women like to have fun, so they seize a holiday like Halloween and go to town with it. Last fall a constant stream of trick-or-treaters braved the open coffin and skulls in the front yard, the blasts of smoke from a bay window, and the sight of two black-robed, pointy-hatted witches at the front door—Inez and her mother—to reach their tiny hands into huge baskets of candy. Holding the basket was Kirsten as Gilligan of Gilligan’s Island, in round-brimmed white hat and red shirt. Occasionally one of the older trick-or-treaters would nudge his buddies and whisper, “Hey, that’s Kirsten Dunst!” But through the long evening she remained, like Mary Jane Watson in Spider-Man, the all-American girl next door.

Kirsten bought this house for her family so recently that it remains only partly furnished. Up a curving wood stairway, her bedroom is a jumble of boxes soon to be moved. The Philippe Starck sofa sits in the hall outside, also awaiting transportation. Out back is a gorgeous view of hills and water, unusual for L.A. Another young actor might swagger a bit at this show of her role as family breadwinner. Kiki, as she’s known to her family and friends, is simply delighted. It’s her contribution to a history of hard work among the family that traces back at least to her great-grandmother’s farm in Minnesota.

Kirsten’s grandmother is a midwestern Swede who grew up doing barnyard chores before moving east to the Jersey Shore. Along with that lineage, Kirsten has German blood from her father, whom her mother met when the two were in college at Carnegie Mellon University; despite marrying at 20, Inez worked for years in fashion design and as a flight attendant for Lufthansa. Eventually, she had the first of her two children with Klaus Dunst, began raising her daughter in Bricktown, New Jersey, and became, to her own surprise, a stage mother.

“She would be in the carriage when we were grocery shopping,” Inez explains of Kirsten at age three, “and she was very animated. People would say, ‘You should have her audition for commercials.’” Neither Inez nor Klaus, a medical-services executive, had any connections to the entertainment world, but Inez resolved to try. “We went into a [New York] modeling agency and that was that. You usually need an appointment, but when they saw her on my husband’s shoulders, they pretended she had one.”

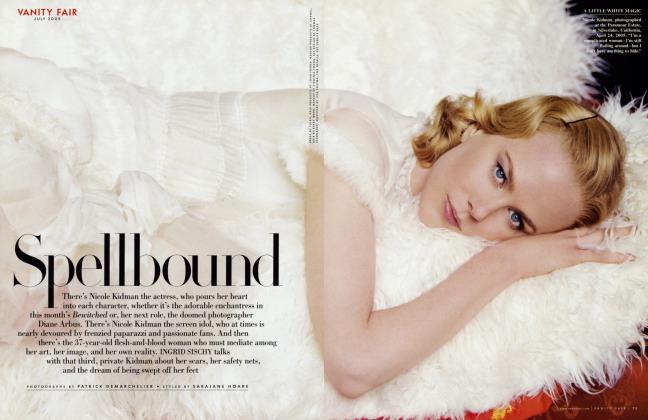

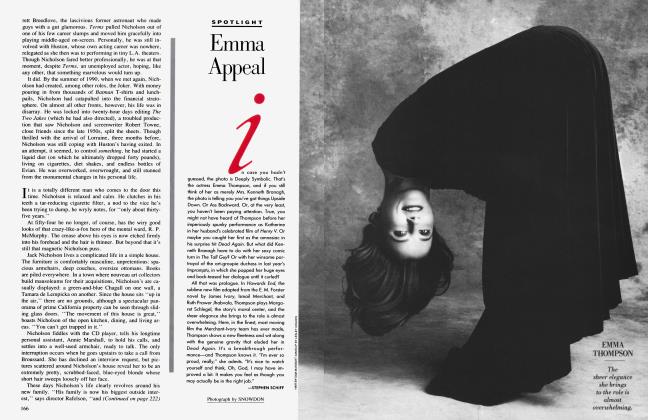

MORE THAN A WOMAN Despite tabloid rumors, Dunst says Tobey Maguire, her Spider-Man co-star, is just a friend. Of her, Maguire says, “She’s very appealing and beautiful. She has a womanly quality, but also a very fun girl quality, an innocence.”

MORE THAN A WOMAN Despite tabloid rumors, Dunst says Tobey Maguire, her Spider-Man co-star, is just a friend. Of her, Maguire says, “She’s very appealing and beautiful. She has a womanly quality, but also a very fun girl quality, an innocence.”

The agency was Ford, which directed Inez to take Kirsten to a first commercial audition—a cattle call with hundreds of kids—for Kix cereal. Kirsten got it. She had the angelic face, the Pre-Raphaelite hair, and an uninhibited charm. “She was a ham,” her mother says. Eventually, Kirsten appeared in more than 100 commercials. Inez swears she let her daughter set the pace. “There were times when I’d say, ‘You got a birthday party and a callback, which do you want to do?’ She’d say, ‘I’ll be late to the birthday party.’” Kirsten’s closest childhood friend, Lindsay Schlisserman, remembers Kirsten getting on the school bus some mornings with her hair up in pink sponge curlers in preparation for an after-school audition in Manhattan. “She’d get teased a bit for that,” Lindsay says, when the girls attended the private Ranney School. “But she was totally O.K. with it.” Kirsten herself recalls riding home from the city after dark in the backseat of her mother’s car, doing her homework in a tiny cone of light. But she was O.K. with that too.

Kirsten won her first movie role at seven—from director Woody Allen. It was a bit part in New York Stories (1989). “All I remember is that we were doing a scene at Tavern on the Green,” says Kirsten, “and I remember Woody getting ice cream for his daughter Dylan, who also was in the movie. He got ice cream for Dylan, but not for me and this other kid. And I remember Mia Farrow getting angry at him for that.” Tom Hanks was nicer; Kirsten was his daughter the following year in Bonfire of the Vanities.

With each new success, the need for Kirsten to move to Hollywood became clearer. Inez took the plunge in 1991; her husband stayed behind.

“When it started to get serious, it was hard for my dad,” Kirsten says cautiously over lunch at a little French bistro of her choice. Her father was always supportive, she says, but couldn’t imagine anything would come of her efforts. “He was just surprised that we were doing so well with it.” Surprised and, perhaps, marginalized, though tension over Kirsten’s career seemed symptomatic of deeper problems. “They were polar opposites,” Kirsten says. “My dad is very straitlaced, and my mom is very vivacious—she has a lot of energy.” The divorce, when Kirsten was 13, merely ratified the obvious. “They were never really happy together,” Kirsten says, “so their divorce never really affected me. I’d rather have them be happy and apart.” Klaus Dunst is remarried and, ironically, now lives a short drive away in Marina del Rey, where Kirsten sees him often.

By the time her parents were divorced, Dunst had beaten out thousands of other young actresses for her role in Interview with the Vampire as an innocent corrupted by jaded ghouls Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt. She earned a Golden Globe nomination for it, too. She began working almost without pause: as spoiled daughter Amy in the 1994 remake of Little Women; as the orphaned, prevaricating sister, Judy, in Jumanji; as an Albanian refugee featured in fake news footage in Wag the Dog.

Often teen actors on such a roll become legally emancipated from their parents, making them adults in the eyes of the law, a move which gets studios off the hook of hiring on-set baby-sitters and tutors for them, and presumably makes them more appealing prospects. Kirsten remained a child in the eyes of the law, struggled through tutoring to keep up on schoolwork during months-long leaves of absence, and tried, at the same time, against the odds, to be a normal kid.

Having a kid brother helped: Christian, five years her junior, kept her grounded. So did doing chores. Kirsten still loves housecleaning, or so she says. She’s a big Windex fan; Lemon Pledge is another favorite. “I think when I get my own place I’m going to love cleaning there too,” she says. Despite her long absences, Kirsten kept close friends and did with them what all teenage girls in the Valley do: go bowling, make prank phone calls, put popcorn in people’s mailboxes, throw rolls of toilet paper out the window, and go trash-can bowling. “You hold a trash can out the window and drive really fast,” Kirsten explains, “and then you crash the trash can you’re holding into another trash can: you let the first one go, and it crashes into the second one.”

Few actors of any age handle comedy and drama with equal aplomb, but Dunst did it with her first leading roles. Drop Dead Gorgeous (1999) cast her in a dark comedy of teenage beauty pageants, and in Bring It On she made cheerleading funny. For grown-ups as well as teens, there was the comic and original Dick (1999), with Dunst as one of two wide-eyed girls who have a crush on President Nixon and get drawn into the vortex of Watergate. (“I’d heard of Watergate,” Dunst ventures, “but I didn’t know a lot about it.”) In that same busy year, Dunst also starred in The Virgin Suicides, based on Jeffrey Eugenides’s lugubrious novel of five sisters who commit suicide, for first-time director Sofia Coppola. And in 2001 she became Nicole Oakley, the disaffected, drug-using rich girl in the underrated high-school drama Crazy/Beautiful.

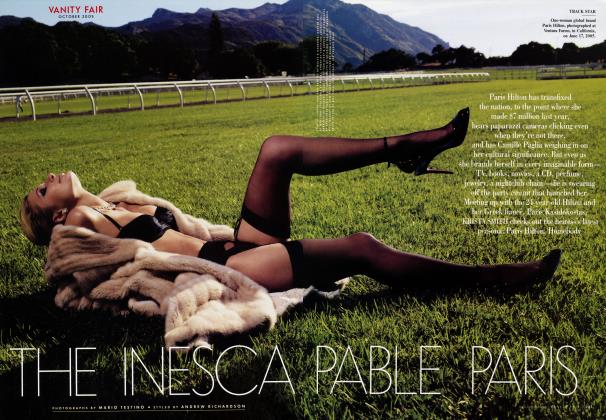

For The Virgin Suicides, Dunst agreed, cautiously, to a lovemaking scene in which she’s all but fully dressed (on a football field at night). But she’s on record as vowing never to act even partially nude. “Nobody is ever going to see my body,” she says. She doesn’t think it’s ever necessary. She’s just as discreet about real-life romance: no talk of a boyfriend on the set in The Cat’s Meow, or anyone else. With those elegant fingers, Dunst pantomimes zipping her lips.

About nearly anything else in regard to her person, Dunst is cheerfully candid. She thinks she has a fat face on-screen and smiles too much; she also thinks her head is too big for her body. She wears makeup to meetings “to hide the dark rings” under her eyes. She eats whatever she wants and never goes to the gym, though she’s noticed she can’t quite get away with anything the way she once did—when she was “young.”

Most actors are cagier about their job prospects than their personal lives. Not Kirsten. She’s gone five months without doing a movie when we first meet, and she’s about to tear her hair out. “I’m so antsy right now! I have to open my own store or my own restaurant, because when I’m not working I go crazy. I’m sort of busy now with getting the house and furnishing it, but still ... Right now I’m so dying to work that I know the next movie I do I’ll put so much energy into it.” By the time we talk again, she’s up in Montreal filming Levity, a small-budget drama starring Billy Bob Thornton, Morgan Freeman, and Holly Hunter. “Yes,” she says, “it is so good to get back to work.”

One thing she won’t do, besides nudity, she says adamantly, is go to college. “My friends in college, they don’t know what they want to do; I do! And I love what I do; college would just keep me away from it.” There are other reasons to go to college, obviously, but Dunst waves off the thought. “I’d like to take classes,” she concedes, “but I’d like to do it on my own time. College is so not for me.”

Strong words, but Dunst is old enough to make her own way—in every way. She’s not even a teenager anymore. As of April 30, she’s 20.

Leading ladies, look out.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now