Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowYOUTH OR CONSEQUENCES

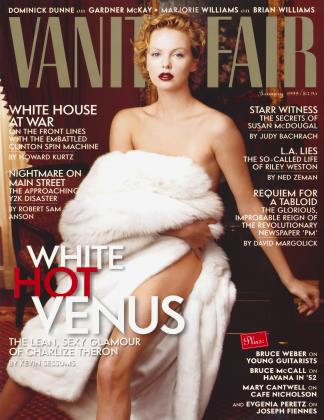

When youth-obsessed Hollywood thought Riley Weston was 18, the actress was showered with opportunities—a writing job and a guest role on the new Warner Bros. show Felicity,; and a $500,000 deal with Disney. Her unmasking as an ancient 32 sent the entertainment industry into an uproar

NED ZEMAN

Show Business

On October 14, the hottest young liar in Hollywood arrived early for her last day of work—a day she knew would end in screaming tabloid headlines. It was eight A.M., well before she usually showed up, lugging her bottled water and her spray-top container of I Can't Believe It's Not Butter, the synthetic, margarine-like substance that had become her personal talisman. Professionally, this was the biggest day of her famously young life. Elfin, doe-eyed Riley Weston, who had dreamed of such moments since she was four years old, was finally getting her shot on the most publicized TV show of the fall season, Felicity, a stylish WB drama about well-groomed college students in Manhattan who break one another's hearts and wrestle with their collective ennui.

Weston had been cast as a precocious teenager visiting for the weekend—a juicy guest role tailor-made for the tiny actress, who was nothing if not the archetype. Several months earlier, she had been among the first writers hired at Felicity, largely because of who she was: a goofy, bouncy 18-year-old who, it turned out, had a knack for writing in the teen vernacular that shows such as Felicity exploit so lovingly. "I'm so not into that," she'd say. Almost as a lark, she'd written a few spec TV scripts, which her agents had peddled as the pitch-perfect work of a teenage wunderkind.

Just a few weeks earlier Disney had signed the kid to a lucrative deal to develop TV shows, and Riley Weston had become a minor sensation, courted by producers and getting big play in the trades. Plus, she seemed like an ideal channeler for the benignly angst-ridden characters on Felicity. "In many ways," Weston told Entertainment Weekly, which placed her on its annual "It List" during the show's ferocious preseason publicity orgy, "I am Felicity," the show's flighty protagonist.

Although Weston was now a full-time writer, she still thought of herself as an actress, and she often left the offices early to attend evening auditions. Meantime, the writing job paid the rent and got her foot in the door while she waited for the plum roles which had thus far eluded her: her resume listed only several small TV and theater credits. Weston made no secret of her acting ambitions, and the Felicity staff sympathized. The producers let her audition for the show's seventh episode, which she had co-written, and she nailed it. After all, she was the model for the character. The character's name was Story.

But when Weston showed up at the set, located in an anonymous industrial park in central Los Angeles, she was a wreck. She couldn't sleep, couldn't hold down food. Her slight, four-foot-eleven frame seemed to be withering; her eyes were rheumy and swollen. My God, she kept thinking, everything I've worked for is going to stop today.

Weston's agents at the United Talent Agency had shifted into full crisis mode, strategizing about how to break some rather awkward news to Disney and the rest of Weston's suitors. A reporter from Variety paged Weston on the set all day; a producer from Entertainment Tonight was also demanding answers. Rumors had been flying around town for days—"vicious rumors," thought the show's co-creator, J. J. Abrams, "crazy rumors"—but now it was obvious to everyone on the set that the rumors were true.

Weston, wearing pigtails and baggy clothes, gritted through her final two scenes and, shaking, made her way upstairs to Abrams's office. Abrams, along with three other producers, was waiting for her. "O.K., well, I lied to you," Weston said. She told them that her real name was Kimberlee Kramer, and that she had been born in ... 1966. Then, as the producers blinked incredulously, the youngest 32-year-old in Hollywood dissolved into tears and asked if she could call her brother, Brad.

It's been a banner year for big lies, buffed I and polished by award-winning journalI ists and the commander in chief. But for months things had been eerily quiet in Hollywood, where mendacity and fraud are the touchstones of daily life. Then along came Westongate, with its convulsive denouement and its inevitable aftershocks of betrayal, sanctimony, and finger waving, and finally Los Angeles seemed normal again.

Within days of Weston's revelation, the scandal was everywhere—in national newspapers, in Time and Newsweek, on every talk-radio station in town; Dateline and 60 Minutes began sniffing around. The early line, in the media and on the Hollywood lunch circuit, was that an industrious young actress had poked her thumb in the eye of Hollywood, and hooray for that. The scandal also raised the evergreen subjects of ageism and sexism in Hollywood, and they, too, were bruited about. Larry Gelbart, the legendary TV producer who wrote Tootsie— the 1982 film in which Dustin Hoffman plays a struggling actor who passes himself off as a woman-spoke for many when he wondered whether Weston was being used as a Hollywood scapegoat and "dying for all our lies." If the suits at Disney and the WB thought that this would be a oneday blip of bad publicity, they underestimated Riley Weston—just like everyone else who had worked with her. By the next morning, Weston had done what everyone in Hollywood does when they screw up. She had hired a publicist.

Two weeks later, as the scandal continI ued to percolate, Weston appears in the I lobby of the Chateau Marmont, a hyperkinetic smurf of a woman lugging a bottle of water and dressed in her signature outfit: baggy sweater, baggy jeans, sneakers. "This is what I'm comfortable in," Weston says, almost reflexively. "I wore baby clothes when baby clothes were so not in. And people looked at me as if I were ridiculous. I've never been into girliegirlie stuff, and I own one skirt. Like, one velvet dress." To say that she looks 19 would be a stretch, but 32 seems impossible. She looks 23. Her eyes widen when she discusses her story, which everyone involved describes as "surreal."

Case in point: Weston's original name is not Kimberlee Kramer, as has been widely reported; it's Kimberlee Seaman. In fact, the perfectly canned "Kimberlee Kramer" is just one of a number of fake names Weston has used since she arrived in Los Angeles 15 years ago, escorted by her mother, Betsy, who had been divorced from Kimberlee's father for many years. They had traveled from horsey Pleasant Valley, New York, near Poughkeepsie, where Kimberlee was a cheerleader voted "Most Popular" during her senior year at Arlington High School. "Everyone liked each other," she says. "Nothing bad ever happened there."

After graduation, in 1984, Weston recalls, the Seaman gals headed west—mother with a wad of cash stuffed into her bra, daughter with big dreams. Reasoning that anything near Hollywood Boulevard must be good, they found a wretched apartment not far from the Ripley's Believe It or Not museum. "Swear on my life," says Weston, who has a gift for dramatic emphasis, "there was, like, blood smeared on the walls." Betsy served as Kimberlee's unofficial publicist before heading back to New York. Eventually an agent took notice, and for the next few years Weston landed the occasional bit role. In between, she babysat all over town, pulling in hundreds of dollars a weekno one plays a more convincing baby-sitter than Riley Weston.

Which was fine until the Dorian Gray Syndrome took hold. With each passing year, Weston looked younger. When she was 21, they wanted her to play 14; when she was 28, they wanted her to play ... 13. "She was this little bitty person," recalls Judy Savage, an agent who represented Weston in the mid-90s. "She was not gorgeous ... just cute. That's hard to place. A certain role has to come along. While she was with me, she only got one."

She sought solace describing a turbulent childhood; she said she was home-schooled.

Kim Seaman

"Believing is the beginning of a dream coming true." Love to all who've made my years fabulous!

Drama 34 Chorus 1234 Hamilton Jl Chcerlcading 123 Stu. Gov't 34

That was Sister Act 2: Back in the Habit, a pointless 1993 Whoopi Goldberg vehicle in which Weston, then 27, played a 15year-old schoolgirl. Weston says that she was called in for the role of John Travolta's teenage daughter in Face/Off and was up to replace 17-year-old Natalie Portman in the Broadway revival of The Diary of Anne Frank. "When she was 30," says a casting director who worked with Weston, "she could have been cast as a fetus."

Savage adds, "Everyone here lies about their age. Even me." Weston's reasoning was simple: "If I'm 29 and the part's for a 14-year-old, I'm not getting in the door. If I say I'm 22, I'm not getting in the door. If I say I'm 18, I'm getting in the door."

By last year, it had all become just too much. Auditioning for the part of yet another eye-rolling teenager, Weston decided she couldn't stomach it. "Crappy," she called the roles. If Hollywood wasn't going to produce credible scripts, she'd just have to write them herself. And if casting directors were going to treat her like a hairtwirling mall rat, well, she'd become the best one they'd ever seen.

Kimberlee Kramer, 30, officially morphed into Riley Weston, 18, in May 1997, thanks in part to her manager and muse, Brad Sexton, whom she had quietly married in 1994. Secrecy was vital—by all appearances, the union made the 26year-old Sexton a cradle robber. An obscure manager with no major clients, Sexton agreed that his young wife had been wasting her myriad talents. It was time for a change, and Sexton was all about change. He encouraged her to find a fake driver's license—even as a casting director who knew her well warned Weston about crossing the line between white lies and outright fraud—and to jettison old TV credits. Managers do this all the time, Sexton reasoned. That's a manager's job.

There was another problem, and it was every actress's nightmare. In 1993, Weston says, a man began stalking her—a terror that would periodically haunt her for years. She covered her windows with sheets; she was afraid to answer the phone at night, as if she were in some awful sequel to When a Stranger Calls. Terrified, Weston eventually moved to the Valley, and her house became a temple of homesecurity technology. Determined to hide, she routinely changed her name on bills and with utility companies.

Meantime, Sexton had grown tired of Weston's complaints about the lack of grown-up roles for waifish, 93-pound 31year-olds. "Go write something yourself," he dared her, and write she did. Sitting at home in her pajamas, gobbling egg whites for sustenance, watching TV nonstop, Weston banged out script after script on her ancient MS-DOS software. She left the house only to baby-sit, and had few friends aside from her Game Boy. One day she rented Ice Castles, the touchy-feely 1979 Robby Benson figure-skating movie, and, clicking the pause button on and off, copied down every single line of bad 70s-era dialogue. Then she wrote a 90s version of the movie. This, she figured, could be the quintessential directorial vehicle for Robby Benson.

Her best effort was a spec TV pilot called Holliman's Way, which was about a quirky suburban family (and which had a starring role for her). Sexton ate it up. So did two of the top Young Turks, Billy Goldberg and Rob Golenberg, both in their 20s, at the vaunted William Morris Agency. Unaware that she was older than they were, the team signed the wee genius. The agents began shopping her work all over town. The timing was golden. The 12to-21 demographic had never been more lucrative, as evidenced by the success of such postcamp teen shows as ABC's Sabrina, the Teenage Witch and the WB's Dawson's Creek. Goldberg and Golenberg have declined comment, but a source at William Morris confirms that her age was the primary hook in the selling of Riley Weston.

Soon the young dramaturge was taking meetings everywhere, including Columbia-TriStar and Touchstone Pictures. Kristi Kaylor, an executive at Pacific Motion Pictures, was briefly attached as an associate producer on Holliman's Way, and has recalled that Weston's unwitting lawyer said during negotiations, "Please don't stand in the way of this poor 18year-old's career." At one point, Sarah Timberman, an executive at ColumbiaTriStar, said to her husband, "Boy, I just met this weird 18-year-old girl—you should meet her.... She's kind of this little kid, and she's a force of nature."

Timberman's husband, Ed Redlich, eventually did meet Weston—in the offices of Felicity, for which Redlich had been hired as co-executive producer. The meeting occurred after an executive at Imagine Television, which produces Felicity, sent Weston's writing sample to the show's co-creators, J. J. Abrams and Matt Reeves. Although the two were established screenwriters, they were television neophytes. "I met with her," recalls Abrams, "and she knew more about television than Matt or I did. She was interesting; she was such a little kid. We thought, Wow, it would be great to have someone on our staff who had a perspective from approximately the age of the show."

Weston hedged. Her first priority was to continue acting. But the suits kept telling her that she needed more TV experience, so in April she began a six-month $60,000plus writing deal with Felicity. Weston was one of the first writers hired on a staff that would eventually grow to eight, almost all over 30. Her writing was viewed as raw but promising—for an 18-year-old. "Here's the thing," says Abrams, using the preface favored by the show's title character. "We were going to hire a creative consultant for that position—someone of that age—so it was like killing two birds with one stone."

For the Felicity writing staff, the first couple of weeks were typical. They spent most of their time kicking around ideas, spilling personal stories, and generally sniffing one another. But Weston just sat there, mute, for hours at a time. When a writer asked how old Weston's brother was, Weston replied, "Oh, 24, 26—1 don't know, maybe 28." Eyebrows were raised, but the staff wrote it off to youth.

A few of the female staffers smelled trouble. "I couldn't understand their hostility," says Redlich, who admits he was completely fooled. "To me, she was just this sad girl who was turning out not to be very valuable." When one writer challenged Weston to say something about herself, Abrams defended his young charge and said, in essence, Take it easy on the kid. Then Weston called in sick for nearly a week. "I don't think she was ever sick," says one of the writers. "I think she was imploding."

"I just met this weird 18-year-old girl. She's kind of this little kid... and a force of nature."

Weston, employing some interesting logic, blames it on her youthful inexperience. "I'm not the smartest of people," Weston says, thinking back. "I was a young writer who didn't know a lot of things. The staff was very smart and talented ... and I was insecure. I wasn't comfortable in that environment at all."

Weston gradually warmed to the staff, up to a point. She filled her office with stuffed animals, hung a Titanic poster on the wall, and mooned about the 17-year-old actor Jonathan Taylor Thomas. (Weston denies swooning over the teen heartthrob, but several witnesses recall such episodes.) One particularly hot morning, Weston arrived at the office wearing boxer shorts, then pretended to ice-dance Torvill & Dean-style on the carpet. When a staffer warned her that a studio executive was in the office, she replied, "O.K., I'll dance for him too," and dance she did. She wanted others to feel her joy. When no one joined in, she thought, How sad that you won't dance with me.

Things grew increasingly Romper Roomish. If anything, the staff agreed, Weston seemed younger than 18. She blushed at sexual themes and profanity—the "f-word," she'd whisper—and once brought in her mother, who thanked the staff for taking such good care of her young daughter. And Weston would go on and on about the virtues of I Can't Believe It's Not Butter—the spray-top kind, which she often carried to meetings. ("That was her thing," says a staffer, "her thing that said, 'Look, here I am, this quirky young girl.'") One day Redlich suggested a story line about Maurice de Rothschild, who attended Duke by pretending to be the scion of the famous Rothschilds. "I remember thinking, This is a news story—I don't know if Riley reads the newspaper," Redlich recalls. "I pitched it to her.... She just stared blankly, as she did a lot of the time."

Although Weston had a knack for snappy dialogue, staffers say, she still offered no keen insights or stories. "Clearly," says one writer, "she had no idea what a 19year-old was like—a 15-year-old, maybe ..." In order to help her along, Abrams quietly outlined an episode for her to write, then quietly rewrote her draft. ("I was sympathetic," says Abrams, who at 24 sold his spec script for Regarding Henry, the critically unacclaimed 1991 Harrison Ford drama—a deal that reportedly earned Abrams more than half a million dollars and an equal measure of criticism.)

Weston understood that she was being treated like a teenager, and she recalls that she was sometimes excluded from meetings and that she never socialized with the staff outside the office. She says she was basically a punch-in, punch-out employee who indicated that she didn't divulge personal details, but her former colleagues find this hilarious. Weston— the ex-cheerleader voted "Most Popular" back in Pleasant Valley, where "nothing bad ever happened"—often sought solace at work while describing a turbulent childhood, during which she was homeschooled and deprived of access to other children. She insinuated that she was inexperienced with "boys"; she cried when she felt that staffers weren't being nice to her; she cried when, on August 26, they decorated her door and celebrated her 19th birthday. "She cried all the time," says a staffer who ministered to Weston's needs. "When she hugged you, it was literally like when you see those chimpanzees cling to their mothers. It was a clinging feeling, like she was desperate."

As fall approached, Weston received more attention than she'd ever imagined. The WB saw her as a publicity magnet, and Entertainment Weekly and Variety took the bait; even Entertainment Tonight was preparing a segment. Weston and Sexton began to sweat. But Abrams soon put a stop to the publicity, and with good reason: he and co-creator Matt Reeves had decided not to renew Weston's contract. As a parting gift for her, Abrams created the small role of Story Zimmer, a ditsy girl who thinks she's a grown-up trapped in a teenager's body.

A mid the chaos, Weston was introduced to Bo Zenga, a writer-producer who is currently working on a movie for DreamWorks. He liked the kid and saw potential in her writing. "I was, like, 'How old is that little girl?'" recalls Zenga, who notes that Weston was wearing a teddybear backpack and a pinafore. If this is her starting point, Zenga thought, then this is really good. Determined to work with her, he excitedly called Billy Goldberg at William Morris. "She left us," said Goldberg, who had just gotten the bad news himself.

Weston had bolted to the United Talent Agency, where she had signed with agents James Degus and Chris Colen. Although agent-hopping is standard Hollywood blood sport, Zenga urged Weston to think twice about ditching the agency that had signed her to the hottest television show of the season. But she had her reasons. Golenberg and Goldberg were "great," Weston says today, but "they didn't get the acting thing." When she wanted to audition for the Broadway revival of The Diary of Anne Frank, Weston claims, the guys at William Morris looked at her, puzzled, until she said, "As in, the attic."

At UTA, Weston was assured, she'd get acting roles and development deals. By September, billing her as a kind of poet in pigtails, Degus and Colen had landed her a two-year, $500,000 development deal with Disney's Touchstone Television. "When you're a salesman in this town," Degus explains with a verbal shrug, "you find a hook." No one at Disney had bothered to call Felicity for a reference. When a Disney executive later phoned Abrams to inform him of the hire, Abrams smiled and said, "She's all yours."

"She cried all the time. When she hugged, it was a clinging feeling... like she was desperate."

But first there was Story Zimmer, a part that had been specifically modeled on Weston—right down to Story's unslakable thirst for I Can't Believe It's Not Butter. Somewhere along the line, she had decided that she'd been relieved of her duties because of the Disney deal, but who really cared if she was spinning the story? Everyone in Hollywood does that, Abrams knew. Everybody lies.

Everyone also gossips, which is why no one at Felicity paid much attention when rumor had it that Weston wasn't 19. Fine, the producers figured, maybe she's 21. Big deal. In typical fashion, none of Felicity's four "teen" stars were actually teenagers— they're all in their mid-20s. Besides, Weston was on her way out—no reason to open that door. Which is exactly what Weston was thinking. "Every day I wanted to tell J.J.," she recalls, "but every day you go, O.K., it's just a number, and I look the way I do, so should it matter?"

Ed Redlich was at a party one night when the Riley Rumor surfaced again. "I can't believe you haven't seen Sister Act 2," someone said to him. Soon Redlich and several other staffers were sitting in the Felicity office, watching the nun comedy in which Weston, who would have been 13 in 1993, looks roughly the same age as she does today. Reacting to all the rumors, a staffer also traced Weston's Social Security number, which indicated that she had been born in 1966—the same year as Abrams's birth. My God, Abrams began to think, she saw the lunar landing. She's not someone I needed to defend so many times.

If Weston is the Monica Lewinsky of this story, then there must also be a Linda Tripp. That would be the anonymous source who tipped off the Felicity producers, UTA, and Entertainment Tonight, which was in the midst of profiling the 19year-old phenom. Guessing the identity of the source has become a Hollywood parlor game, and everyone has a theory. In fact, there were at least two sources, one of whom knows Weston professionally.

Brad Sexton knew the jig was up, and told Weston to "come clean" about her socalled life. Weston told her agents, who were floored. They'd seen plenty of clients who stretched their ages, but this was nuts. "After we talked, I remember saying, 'O.K., kiddo, I'll see ya,'" Colen recalls. "Even after she admitted everything, I was still talking to her like she was 19. That's just how you get around her."

Weston arrived for work that morning accompanied by a bodyguard. She looked exhausted, and said she'd been having stalker problems again. I've let everyone down, she thought, and I'm gonna lose the best clip of my life. Because she had scenes to film, however, no one said a word about The Secret. She and Redlich chatted mindlessly about the day's pumpkin soup. On film, Weston looked wan but impressive.

Weston was summoned to Abrams's office, where she sat with Reeves, Redlich, and producer Mychelle Deschamps. Without prompting, Weston confessed her age, apologized, and began sobbing like a child. "Look at me!" Abrams recalls she cried, nearing hysterics. "I'm a physical freak. This is who I am. This is what I look like. I dress like this because I don't like people looking at my legs. That's why I look like this. What else can I do?"

The producers listened patiently, wished her well, and, sitting her in a conference room, let her call her brother. Fearing for Weston's mental state—and warning that the press would soon be all over her—they reserved a room for her at the Chateau Marmont, where she wouldn't be bothered. Reporters were already calling every five minutes. Redlich peppered her with questions: Why? How? Only weeks earlier, she'd gone on and on to him about her crummy teenage life, and now he was riveted. Deschamps offered the name of a therapist, saying, "You should talk to someone." Weston replied, "I already have a publicist."

She was still crying, so a production assistant was ordered to drive her to the hotel. All day Weston had been thinking, Who did I hurt? Who did I physically impair? What did I devastate? What did I endanger? As they headed up Fairfax Avenue in Weston's S.U.V., her despair quickly shifted to anger. "Everyone does this," she kept complaining. "Why are they punishing me?" Weston's "brother" was waiting for her when they reached the Chateau Marmont, and the production assistant recognized him. It was Brad Sexton.

The aftermath was a festival of misinformation, and it took a while to sort things out. At UTA, Degus and Colen were doing damage control—pleading ignorance, pleading for understanding, trying to mend fences all over town. Agencies don't conduct background checks, they explained. "To some extent, we probably got caught up in the whole youth craze," says Degus, who, at 27, is a walking example of it. "Maybe we needed her to be 18."

While some executives were understanding, others felt duped, none more so than the higher-ups at Disney, who were said to be embarrassed. During a building-dedication ceremony, Disney chairman Michael Eisner was asked questions about an impish, 93-pound actress he'd never seen before.

(He pleaded ignorance.) "The one thing Disney hates more than anything is scandal," says a source. "They want out, but they fear an age-discrimination suit."

The Felicity staff reacted with a confluence of shock, anger, and amusement when Weston was portrayed in the media as Hollywood's latest slaughtered lamb. No one cared that Weston had fibbed in order to act. Several years ago Edward Norton, a then obscure Yale graduate, passed himself off as a southern rube while auditioning for his psycho-cracker role in Primal Fear. What bothered the Felicity staff was the fact that, as Abrams puts it, "someone who was working closely with us for months was deceiving people who spent hours of their time helping her while she was in crisis about being 19 in Hollywood."

Felicity staffers still occasionally stop typing and, apropos of nothing, think, / can't believe she's 32. They feel suckered by a writer who, they say, used her "youth" to camouflage inferior skills. Some blame Brad Sexton, whose relationship with Weston is unclear. (Neither will discuss whether they are still married, and the word around town is that his career is over before it started.) "Perhaps we'd be angrier if we honestly believed that Riley was in complete control of the charade," says Redlich, who feels sorry for her, "that when she got home at night she poured a scotch, put on a short skirt, and laughed at us."

The next day the staff watched Weston as she was unmasked on Entertainment Tonight —watched as she laughed, flipped her hair back, and spoke with a certain self-assurance they'd never seen. "Well, she seemed more mature," says Redlich. Even more bizarre was the revelation that in the mid-80s Weston had briefly attended New York's Adelphi University—bizarre because the Felicity staff once considered sending her to college.

"Perhaps we'd be angrier if we believed that Riley was in complete control of the charade."

These claims bug Weston, who sent written apologies to most of the Felicity staff. "This is me," she says, adding that at home she does not wear tiaras, does not booze it up, and does not speak in a deep, sexy voice. "I'm not going to apologize for looking the way I look." Tonight, she says, she will go home, put on her pajamas, sit in front of the TV, eat egg whites, and play with her Game Boy. "Should I not do that because I'm over the age of 21?" she asks, mocking the skeptics. "No chair swiveling! No running outside!" And she still can't understand why she's been singled out in a city that celebrates Courtney Love's brand-new body and Madonna's Etonian accent.

Lately, Weston has made herself the poster child for the serious problem of ageism in Hollywood, where writers over 30 face ever diminishing job prospects. Just this morning, she was commiserating about this with her new friend, producer Larry Gelbart, who reminded her that if Hollywood contracts had morals clauses, no one would work. She was "psyched" that a Hollywood legend had rallied to her defense. After she hung up, Weston says, she sent him one of her scripts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now