Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFAIRY TALES CAN COME TRUE...

Christopher Hitchens

A new movie starring Peter O'Toole and Harvey Keitel recalls the 1920 "fairy photographs" hoax that fueled the feud between Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini. But as the century ends, fairies are back— they may even oust angels as the mythological fetish of the moment

While making a film on religious racketeering in Los Angeles, I once went to interview the manager of the Bodhi Tree Bookstore: a spiritual supermarket in West Hollywood. He lurked lugubriously in a room piled high with books on healing, magic, and the transcendent. The session was not a howling success, partly due to his dismal catarrh and also to the weeping sores which covered all the unbearded bits of his face. Business appeared brisk and I strove to brighten him up by pointing this out. Yes, he agreed, in a voice that could have come from the tomb, sales were pretty strong. Anything going especially well these days? I cheerily inquired, hoping to salvage something from the shoot. He turned his suppurating features to the camera and, in the tones of a man forced to choose between the noose and the blade, announced that "angels are very big this season. Anything about angels."

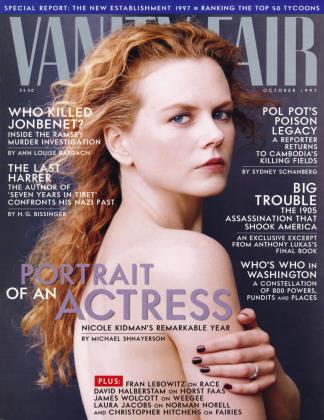

That was then, of course. The angels have fluttered off, at least for now, and as the beating of their wings dies away we hear the tiny pipes and tripping feet of the fairy folk. Soon to fall from the press is Fairies: Real Encounters with Little People, an anthology of credulity slapped together by Janet Bord. A movie entitled Photographing Fairies, starring Ben Kingsley, is in readiness, and its producer, Michele Camarda, has candidly announced that 1997 is, in effect, the Year of the Fairy. "We are tapping into the millennium fever, where people are seeking something they cannot find in contemporary religion." The film takes its fictional point of departure from a real episode in the long, loopy history of psychic phenomena. It has been exactly 80 years since two British schoolgirl cousins, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, returned from a ramble in Cottingley, West Yorkshire, and blithely declared that they had captured fairies on-camera. The Case of the Cottingley Fairies, a book on the controversy by the Yorkshire journalist Joe Cooper, is to be published in England next month. It will coincide nicely with Fairy Tale: A True Story, another feature film based on the Cottingley episode, more in the docudrama style, in which Peter O'Toole plays Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Harvey Keitel takes the part of Harry Houdini. In their day, these men were the antagonists in an argument of Roswell-like proportions.

'Nineteen ninety-seven is the Year of the Fairy.'

In 1917, Elsie and Frances, aged 16 and 10, respectively, borrowed Elsie's father's Midg camera, loaded with one cumbersome old-fashioned plate, and set off down the stream, or beck, at the bottom of their garden. The plate they came back with, when developed by Frances's father, seemed to show her festooned by a posse of prancing fairies. In the face of parental skepticism, and given a certain amount of notice, the two girls produced more exposures over the next few months. But the unimpressed senior members of the family kept the miracle dark, so to speak, until 1919, when Elsie's mother attended a local meeting of the Theosophical Society. This group had quite a vogue in the immediate postwar, because the loss of millions of men and boys between 1914 and 1918 had created a huge appetite for communion with the dead and missing. Mrs. Wright shyly mentioned the existence of the plates to the visiting speaker, who put them into the hands of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Doyle had lost his own son, Kingsley, in the war and had become a fanatical spiritualist. Utterly persuaded by the photographs, he wrote a then famous essay called "Fairies Photographed: An Epoch-Making Event," and submitted it to the Strand magazine. It ran as the Christmas cover story in 1920 and formed the core of a later book. Conan Doyle also asked the two girls to produce more photographs, which at first they found they could not. Then they discovered they could—to the tune of three more. Then they stopped altogether. We do not, for the purposes of a controlled experiment, have the plates of the failed shots, but we do have the "Cottingley Fairies" sequence: five exposures which convinced, and still convince, many people that "there must be something in it."

The episode highlighted the growing dispute between Conan Doyle and his onetime friend Houdini. The latter, having lost his adored mother and having tried the "spiritualist" route of re-establishing contact, had become utterly persuaded the other way. He toured far and wide, exposing and denouncing the callous hoaxes of the ectoplasm-artists and of those who dealt, for coin, in burblings from the beyond. He claimed that he could explain or duplicate any of the "special effects" produced at any supposed seance. This cut Sir Arthur to the very quick. What an ideal confrontation. In one corner, the noble creator of Sherlock Holmes and the respected author of forensic and detective prose. In the other, the hardscrabble immigrant son of a Hungarian rabbi, making an equally fabulous salary out of prestidigitation. But it's the magician who holds out for hard evidence and the use of reason, while the old sleuthfancier falls to pieces in a Watson-like fit of buffoonery.

Fairy Tale is directed by Charles Sturridge, who brought Brideshead Revisited and A Handful of Dust to the screen. As before, his evocation of period and setting is masterly. He can "do" the London of the music halls and the magic shows, the country houses of Doyle and his circle, and the hermetic and fey world of a cutoff hamlet in the Yorkshire dales.

Only in context does the Cottingley affair make any sense, because the actual pictures were of a "Don't make me laugh" quality. Conan Doyle's 1922 book, The Coming of the Fairies, and the pro-fairy propaganda campaign waged by E. L. Gardner of the Theosophical Society could have succeeded only in a time when popular photography was in its infancy, and when people tended to believe that the camera could not lie. It also helps to have a fairy-saturated popular culture. Chaucer's Wife of Bath goes on about the fairy ancestors of the English in The Canterbury Tales. Edmund Spenser's Faerie Queene, a suck-up to Elizabeth I, draws on the same mythology. And there's always A Midsummer Night's Dream. Nearer the time of Cottingley there had been J. M. Barrie's Peter Pan and the elfish children's illustrations of Arthur Rackham and Edmund Dulac. My own favorite is the sinister midVictorian painter Richard Dadd, who executed two masterpieces on spectral themes. Dadd was a barking lunatic who, while confined in Bedlam hospital for the bloody slaying of his father (whom he mistook for the Evil One), painted Contradiction: Oheron and Titania and—one of the great canvases of all time in my opinion—The Fairy Feller's Masterstroke. (Somehow it's eerily appropriate that Contradiction was acquired in 1992 for $3.1 million by Andrew Lloyd Webber.) Good old Dadd reminds us that these illusions are not just whimsy and romance but have their noir side. Conan Doyle himself probably understood this in a confused way, since his own father also spent many years in a Victorian asylum, drawing fairies as if they were going out of style.

'Aren't the fairies dressed somewhat like fashion plates?'

To my immense surprise, both Joe Cooper and Charles Sturridge return a sort of open verdict on Cottingley. No doubt this makes for a more intriguing book and a more multifaceted film. And don't get me wrong. I'm not one to spoil children's fun by brutish literalmindedness. I dress up as Santa with the best of them ("Mummy, Father Christmas has fallen down again"). But actually, Elsie and Frances inverted the usual process. They were a pair of rather knowing children who did a great deal to sow superstition among adults.

Take a look at the first photograph. It "shows" Frances posing with a gaggle of merrymaking fairies. And at the second. It "shows" Elsie allowing a gnome to clamber on her skirt. Take another look. Frances isn't even directing her gaze at the tiny sprites. And what has happened to Elsie's hand in the second photograph? In both cases there are explanations from true believers. Conan Doyle and his friends declared that Frances was more fascinated by the novelty of a camera than oy the appearance of tiny persons from another world or dimension, and thus fix d her eye on the lens. As for Elsie's grotesque fingers, they must be a trick either of the light or of (aha!) the camera or an ectoplasmic manifestation! A vast audience followed this ridiculous dispute. Since the girls had never asked for any money, it was argued that their naivete favored their claim (a logic that would have amazing consequences if applied in general). Innocence was at a premium, since Elsie was approaching the awkward age and, as Conan Doyle gloomily minuted, "I was well aware that the processes of puberty are often fatal to psychic power." (Don't you hate it when that happens?) And then take another look. Aren't the fairies dressed and accessorized somewhat like fashion plates? And isn't the gnome a bit like our expectation of a cartoon? Who does these babes' hair? Where are their dressmakers? Why do they care about our standards of modesty? And don't they remind us of something? To be exact, of the drawings of fairies in Princess Mary's Gift Book, a popular volume for children published in 1915.

Let me not keep you in suspense. Joe Cooper had been in touch with Elsie and Frances until close to the end of their days—they survived into the

1980s—and one fine afternoon in September 1981 he kept a date with Frances. She asked him to take her to Canterbury cathedral, leave her there awhile, and pick her up, and then she told him, of her strangely disinterested gaze in the first photograph, "From where I was, I could see the hatpins holding up the figures. I've always marvelled that anybody ever took it seriously." And yes, she had owned a copy of Princess Mary's Gift Book, and given it to Elsie for tracing purposes. Quite simply, the two girls had got together, cut out some fairy silhouettes from cards, propped them up in the grass, and snapped away. The detail about the hatpins is especially worth having because one of them protrudes faintly through the middle of the gnome photograph, and this childish blunder caused Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to pronounce gravely about gnomish navels and umbilical correctness, and the exciting (to him) idea that the little people reproduced in the same gross way that we do. But having led everyone on a fanciful dance for decades, Frances had decided to let go and come clean. In 1983, Elsie told the Daily Express the same story. The hoax had got out of control, she said, when someone as famous and beloved as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle became involved. "I felt we couldn't now say they were fakes. It might have upset him dreadfully." E finita la com media.

But it's not so easy being a fairy-flattener. You take your shovel, you squash them like roaches and ignore their tiny yells, and then they leap up again giggling and gibbering in some other part of the garden. I had a long talk with Joe Cooper, a jovial and intermittently learned man who asked me my birth sign, enlightened me about my astral position vis-a-vis Mercury, and informed me about ectoplasm, about reincarnation in what he revoltingly termed "solid form" after three days, and about much else besides. In spite of having been given, somewhat against his will, every evidence of fraud, he is still convinced, as he maintains Frances was convinced, that the so-called "fifth photograph" of a gossamer fairy bower is absolutely genuine. As an adviser on the making of Fairy Tale, he says that without the "fifth photograph" he doesn't think Sturridge would have gone ahead. And then he lowers his voice. "Here's a bit of scoop for you. Frances was a suicide at the end. And Elsie wanted to kill herself, but her son wouldn't have it. They both had very painful years of illness. You see—the fairies like you to play straight with them."

Now, as it happens, this is exactly what Conan Doyle insinuated about the death of Houdini. The master illusionist had been injured in a freak accident offstage, and had died in agony from peritonitis, and the spiritually correct view was that this was otherworldly revenge for his subversive views about the crappiness of the occult movement. (Let us note in passing that men like Conan Doyle and Cooper, who normally hail fairies as lovely and stainless visions from wherever, can switch automatically when pressed, and give these same delicious pixies the power to inflict osteoporosis, peritonitis, cancer, and other less ethereal visitations.) Sturridge, when I spoke to him, said that he had always been "fascinated by the idea of a separate order." All right then—which one? The sweet, innocuous sprite or the rodent cell that metastasizes into the newborn's testicles? Which of these represents the unseen purpose? I only ask because Sturridge attended the same Jesuit school as Conan Doyle, and by the second millennium there ought to be some kind of on-therecord answer to this question.

His second reply—that "I've always been interested in why people want to believe things"—was altogether more promising. As the resigned old Jesuit Father Mowbray says in Brideshead Revisited, "the trouble with modern education is you never know how ignorant people are. With anyone over fifty you can be fairly confident what's been taught and what's been left out. But these young people have such an intelligent, knowledgeable surface and then the crust suddenly breaks and you look down into depths of confusion you didn't know existed."

I attended a screening of Sturridge's beautiful film in the company of Dr. Michael Shermer, the editor and publisher of Skeptic magazine and author of the splendid book Why People Believe Weird Things. Fairy-flattening is only one of Shermer's regular tasks these days. He also has to go on the chatshow circuit and combat Hale-Boppers, regression therapists, creationists, Roswell freaks, Bible Code babblers, Holocaust deniers, Farrakhanite spaceship cultists, astrologers, ESP artists, and escaped psychics. It sometimes seems as if the world's most advanced modern society has collapsed utterly into the worship of pseudoscience, with people possessing just enough education to get everything spectacularly fouled up in their minds. What could be more enthralling and awe-inspiring than to follow the adventures of Stephen Hawking, a genuine devotee of science and history and literature? Yet people will spurn this chance in order to gape at a palpably confected video of alien autopsies. It's like throwing away the truffle in order to gulp down the wrapper.

But there is always hope. Allied with Shermer and the Skeptics Society is James Randi, the Houdini of our time and a tremendous popularizer of reason and mental hygiene. There's nothing dry about Randi. He has unpacked Uri Geller, tossed and gored George Harrison's levitating maharishi, showed the dowsers and water-diviners to be all wet, and untrousered the faith healers and psychic surgeons. It's been 15 years since, in his fabulous book Flim-Flam!, he showed (without any knowledge of the confessions of Frances and Elsie) that the Cottingley snaps—particularly the "fifth photograph"—were a not-veryingenious practical joke that got out of hand. Like his role model Houdini, Randi has issued a challenge to all peddlers of paranormal piffle: if they will submit to a test of their miraculous skills, under agreed-upon controlled conditions, and bring off a result, he will pay them $1.1 million. Since he doesn't have the money himself, Randi has a thing called the 2000 Club, whereby supporters pledge a minimum of $1,000 to insure him against any defeat at the hands of the wizardwitch-and-warlock community. (Penn and Teller have kicked in $100,000.) Some takers so far, but no winners, and the bounty is getting bigger all the time. As my contribution to the millennium celebrations, and the tsunami of piffle that is about to break over us, I have pledged my apartment to the 2000 Club, and I expect to be living there, reading stories of enchantment to my children, but with no pixie-ridden brook to excite any feebleminded adult neighbors, at least until I move, or until I have passed over to that undiscovered region that is beyond the reach of Tinkerbelle's hideous vengeance.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now