Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowNo One But Norell

To women such as Lauren Bacall, Babe Paley, Lena Home, and Lyn Revson, the Norman Norell label meant Paris-couture-class fashion made on Seventh Avenue. To Norell, the midwesternborn designer behind the first ladies' tuxedo suit, the first flash of 60s mod, and the first U.S. designer perfume, his label meant everything LAURA JACOBS chronicles the dramatic ascent of America's pioneering fashion icon

LAURA JACOBS

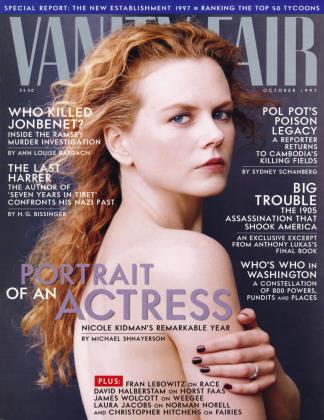

Norman Norell's white-lily, black-tie fashion shows were like theater premieres.

NORMAN NORELL New York

That's all his label said. The name was in block letters, and the city was smaller, centered beneath. No manufacturer's name marred the white space. No "Paris," "London," "Tokyo." Just "Norman Norell" and "New York."

He was from Noblesville, Indiana, a sickly child, a slight man. But in the history of fashion he is huge. Norell isn't famous for a New Look like Christian Dior, though in that big year of 1947 Dior bought Norell's Triangle Coat and proclaimed it "coat of the year." (He forgot to mention that Norell, who lengthened skirts and nipped waists in 1946, actually beat him to the New Look.) Norell didn't make revolutionary use of black jersey like Coco Chanel, though his little jersey dresses were legend in the business. He didn't hide behind a wizard's white curtain like Cristobal Balenciaga, though he could be as shy as the mystical Spaniard, could set a sleeve as serenely, and was often called "the American Balenciaga."

Norman Norell might have gone the couturier route of his two American contemporaries Charles James and Mainbocher—he had the training and the imagination. But he did something infinitely more difficult. He settled into Seventh Avenue, with its industrial rows of sewing machines, its hard nose for cash, its back-of-the-hand attitude toward designers, and he made the highest-quality clothes—couture quality—the wholesale had ever seen. American designers today may be C.E.O.'s with I.P.O.'s (forget hemlines— is their stock up or down?), but Norell hit a different kind of height, one that prepared the way for Ralph and Donna. Out of rag-trade anonymity he emerged as our first Fashion Avenue icon, his career a long climb to that lovely label that said it all by saying only "Norman Norell New York." When he died 25 years ago, in 1972, the headline on the New York Times front page was a one-man show: NORMAN

NORELL . . . MADE 7TH AVE. THE RIVAL OF PARIS.

Norman David Levinson was born with the century, in 1900, the younger of two sons. His mother was Methodist, his father Jewish, the family trade haberdashery. The earliest piece of Norman lore is his response to Methodist Sunday school: he hated going, balked like a mule, and threw his service penny in the dirt. The earliest picture of Norman, from around 1905, is a photograph of a boy in a sailor suit: his big brown eyes seem to take in every detail. Stubborn and seeing— Norell in a nutshell.

Weakened by rheumatic fever, Norman was out of school as often as in, and spent days in bed leafing through his mother's fashion magazines, preferring paper dolls to baseball. He was spoiled, but no one took him for a sissy. "From the beginning, he got to be known as artistic," says his nephew Alan Levinson. "He was the first boy in the county to have a corduroy suit." And the first boy in America (maybe in the world) to have a round bed, which he designed himself. "My family," Norell said, "they were really embarrassed about that bed."

When the Levinsons moved to Indianapolis, Norman worked in his father's hat shop; its motto: "$2 hats and $1 caps." "My grandfather put him to work in the store trimming the windows," Alan Levinson recalls. "That was his first artistic job." Indianapolis was the beginning of something else as well. A major stop on the Keith Circuit—shades of Gypsy—the city saw all the best touring shows and vaudeville, and because Norman's father advertised in the program, the family saw it all, too, for free. Norman was smitten and decided to be a set and costume designer.

Look up "Norell" in any fashion encyclopedia and you find that the Dean of American Fashion had a pretty motley C.V. It's also riddled with myth. Between the motley and the myth, the evolution of Seventh Avenue runs parallel to the ascent of Norman Norell.

1919, Parsons School: It's listed in every book about Norman, but he never went there, because he wasn't accepted. According to a friend, he used to say, "The only people that could get into Parsons in those days were girls from good families who were strictly 100 percent Wasp and who couldn't get by Mrs. Chase at Vogue.'' Later in life, flattered that Parsons wanted to claim him as an alum, he conspired with the story. But even then he gave a naughty twist to the tale, telling younger friends that, yes, he'd gone to Parsons, but one day Mr. Parsons called him into the office and chased him around the table, so he never went back.

1920 to 1922, Pratt Institute: When Norman won a contest for blouse design ($100 prize), his path swerved toward fashion. He changed his surname to Norell, decoding it this way: "Nor for Norman, / for Levinson. With another / added for looks." Bien sur! In those days a dress designer had to be French.

1922, Paramount Pictures, Astoria Studio: Norell didn't actually work for Paramount; he worked for Gilbert Clark, a celebrated, now forgotten theatrical designer who hired the green kid straight out of school and had him designing costumes for Rudolph Valentino (The Sainted Devil) and Gloria Swanson (Zaza). Swanson liked to make it clear who was boss. She carried a six-foot staff to her fittings, struck the floor twice for attention, then gave orders to her maid, who relayed them to Norell two feet away.

1923, Brooks Costume Company: "The tone of the job was set by my first client," Norell once said. "I asked the man what he wanted. 'Anything that goes with a black patent-leather hat.' "

1924 to 1928, Charles Armour, dress manufacturer: At Armour, Norell hit on his vision of sport habille, dressy sportswear, and had his first success, a gold lame dress with a wide suede belt. It was also his first failure: that

wide suede belt turned the dresses purple at the hips. They all came back and Norell was out.

1928 to 1940, Hattie Carnegie, design house: This was Norell's big break and an education equal to a stint at the Ecole de la Chambre Syndicale in Paris. The Carnegie label was monographic in its own way. It meant Paris fashion made on Seventh Avenue. Carnegie had a stable of designers (an illustrious bunch, later including the design comet Claire McCardell), and she brought a keen editorial eye to the cutting-room table. Norell got the job through sheer chutzpah. Or was it extreme modesty? Hearing that head designer Emmet Joyce had left, he went to Carnegie's office with sketches and waited all day. "He just sat there in the office," his nephew relates, and by chance caught Carnegie's eye as she was leaving. "He said, 'If I could work for you for several weeks, I'll do it for nothing. And I'll even pay for material I ruin.' That's how he went to work for Hattie Carnegie."

'Ilearned everything I knew from her," Norell would later say of Carnegie. But she wasn't easy. He was retiring, she was tough; he was self-contained, she had tantrums. Still, he stayed with the taskmaster for 12 years, learning the Paris ropes, dissecting the couture they brought back to New York (Vionnet, Chanel, Patou), perfecting technique, and, most important, figuring out how to recast Parisian proportions for the American shape, the American life. At Carnegie he also began dressing celebrities—Joan Crawford, Constance Bennett, Paulette Goddard, Katharine Hepburn. Which brings us to our first lesson in Norellia—those events, themes, motifs that are the sine qua non of Norman's life. These are not to be confused with Norellisms, favorite fashion gestures like sable trim, pussycat bows, big buttons, culottes, polka dots.

Norellia No. 1: Lady in the Dark. The Kurt Weill-Ira Gershwin musical of 1941, about a fashion-magazine editor who gets psychoanalyzed, had costumes for Gertrude Lawrence designed by "Hattie Carnegie," i.e., Norman Norell. These costumes caused a blowup between Carnegie and Norell, but the exact reason has remained "in the dark." Here's the historybook explanation. Carnegie was out of town when Norell designed the costumes, and threw a fit when she finally saw them. They were too extravagant, too expensive, to mainstream, especially the blue gown with upside-down ostrich feathers. Norell quit. Here's the inside story. Hattie and Norell both designed dresses for Lawrence, who naturally preferred Norell's. He doubled the insult by saying, "Oh, Hattie, you take care of the old-lady clothes." Norell was fired. Final diagnosis, according to Denise Duldner, Norell model and his last assistant: "He was ready to go, he just needed a catalyst to go."

And he went—out of the frying pan into another frying pan, from Hattie Carnegie to Anthony Traina. But this time there was a deal: more money if the label read "Traina," less money if it read "Traina-Norell." Norman chose less money. Far less. From more than a thousand a week at Carnegie he dropped to a starting salary of $500 a week at Traina. "At Traina-Norell I think he finally got $800 a week," claims designer Louis Clausen, "but that was nothing for a man of Norman's stature." Still, Norman chose right, and in more ways than one.

"He was mean as hell," says Neiman Marcus president Stanley Marcus of Anthony Traina. "But he was a master behind-the-scenes man."

"Tony Traina was one of those big, old-time Seventh Avenue manufacturing guys, and they really ran their company," explains Carrie Donovan, former fashion editor of The New York Times Magazine. "In those days, when you were the designer, you made the collection and then you got out of town.

In which case they would alter the designs. But they didn't alter Norman's."

Lynn Manulis, daughter of the legendary Park Avenue boutique owner Martha Phillips and herself a champion of young designers: "Traina was a perfectionist. There was no margin for error with this man. He kept Norell a prisoner in his office. Nobody ever saw Norell, he was a phantom." But he did get out for lunch.

Norellia No. 2: Schrafft's, 43rd Street, east of Broadway. Members of the "Schrafft's Lunch Club" likened it to the Algonquin Round Table, but this table was small and square, and these lunches were one hour, one drink (when someone was on the wagon, no drink). Members of the club: Norell and Seventh Avenue colleagues Bobby Knox, Wilson Folmar, Alan Graham; later Louis Clausen, Frank Adams, John Moore; and in the 60s, Women's Wear Daily chief John Fairchild. Gals were rare, but invitees included Carrie Donovan, manufacturer Mattie Talmack, and designer Ruthie Alexander.

Out of rag-trade anonynuty Norell emerged as our first Fashion Avenue icon.

In the movie Sweet Smell of Success, Burt Lancaster says to a sly bimbo, "Your brains may be Jersey City, but the clothes are Traina-Norell." And a sweet success Traina-Norell was, too, right from the start. "The best-made ready-to-wear merchandise in the world was Traina-Norell," declares Donovan. "Norman made these clothes that had a poster quality to them." And he made them from 1941 to 1960, still trekking to Paris collections, buying his fabric in Europe, developing an identity, not with a capital / (as in flamboyant self-expression), but with an unstinting eye for workmanship, fit, the richest materials, and a pristine (but never precious) silhouette.

It was in the early 40s that America's fashion press and buyers started paying attention to Seventh Avenue—World War II was on and the Paris couture was otherwise Occupied. was in the 40s—and in his 40s—that portraits of Norell started making the papers. How debonair he looks, a cross between Cary Grant's dark directness and Fred Astaire's small-framed, elfin elegance. There's a real RKO gleam to him, the Swing Time cut of his suits, those smiling eyes. It was in 1943 that Norman won the first Coty award (he later fretted that Claire McCardell should have won it first), and in 1943 that he turned down Harry Cohn's offer to design for Columbia Pictures in Hollywood, suggesting Jean Louis for the job instead (which launched Jean Louis and also, shrewdly, got an up-andcoming competitor off the East Coast).

"Mr. Norell's dream was to have his own business," says Denise Duldner. "He did not want another boss." After Swanson and Brooks and Armour and Carnegie, and deep in the trenches of Traina—a boss, not a partner—Norell aimed toward autonomy. He and Traina, however, with their stratospheric standards, were a formidable team. Bottom-line as he was, Traina stayed out of Norell's way when it came to designing. Louis Clausen recalls, "When Norman did the first black dinner suit with a bow tie for a woman—it would be a smoking today—Traina looked at it and said, 'Norman, don't you think that's a little Lisbon?' Norman didn't pay any attention. It was a big, big success." (And pre-YSL by a decade.)

"He had this idea of a sportswear mentality done in something opulent or unexpected, and that has always been a favorite idea of mine," Bill Blass suggests. "I remember one spring I was at the Ritz in Paris having lunch, and Bogart and Bacall were there. They were just married. And she was wearing Norman Norell's gray flannel jumper, a childlike jumper, with a white organdy blouse with rather big sleeves. And no hat. It was a delicious way to look, and so un-French. It really created a sensation, and this was at the height of Paris clothes."

Seam for French seam—not to mention silk linings and interlinings, invisible hems and hand finishing—a Traina-Norell stood up to a Paris original (it could be just as expensive). And Trainas were younger, fresher, with an American snap, a Manhattan swagger. In the 19 years the label said TrainaNorell, Norman became an institution, and by the time Tony Traina was ready to retire in 1960, certain Norellia were institutions, too. For instance:

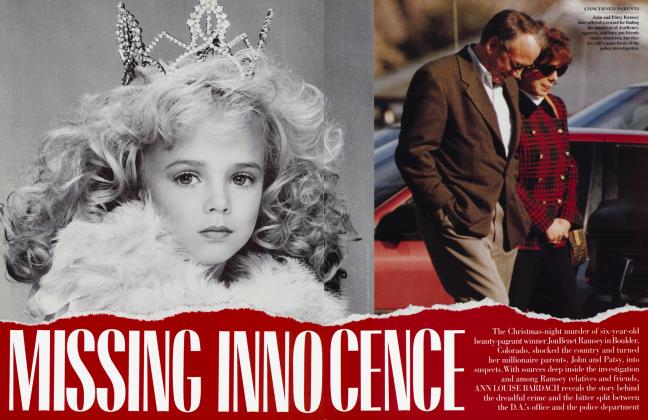

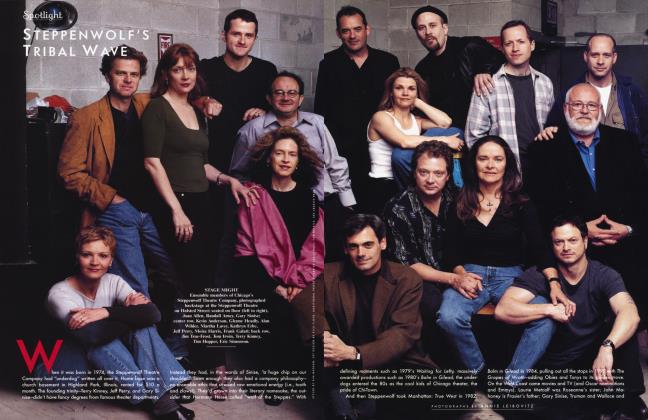

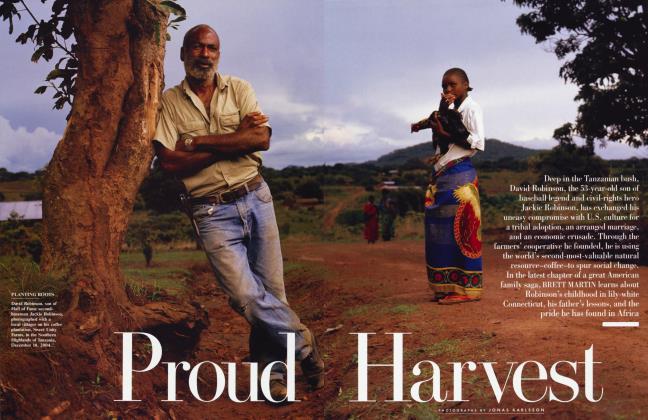

Norellia No. 3: The nine P.M. openings. Norell's white-lily, black-tie fashion shows, though silent, were like theater premieres, complete with champagne intermission. (Norell called the models' earrings "spotlights.") "It was like going to Shangri-la," exclaims Lynn Manulis. "You sat on little gold ballroom chairs, and you saw everyone that was anyone in the fashion world on that 10th floor."

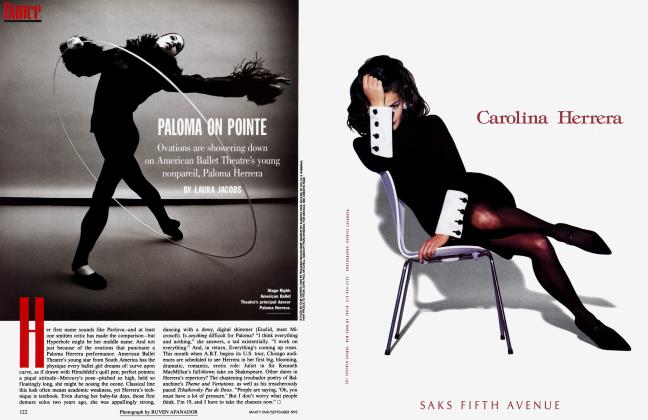

Which leads to Norellia No. 4: The cabine. Though he called them "the Kids," the rest of the industry referred to Norell's models as his "cabine" He fitted each collection on four girls only, which is why the coveted end-ofseason samples could be snapped up the second they got to Loehmann's: women called and said, Save me the Claudias, the Dorines, the Denises. "Mr. Norell liked his living mannequins to look like a store mannequin," says model Yvonne Presser. "He wanted the clothes to make the statement, not the girl."

And, of course, Norellia No. 5: Mermaids. Lauren Bacall wore a black one in Applause, Jane Fonda, a blue one in Klute; Lena Home had a gown in garnet; Lyn Revson swam through society in rainbow hues through the 50s and 60s. What made these sequined sheaths the most expensive dresses in America (as high as $3,500 in 1967—the equivalent of $15,000 or so today)? Jack Miles of I. Magnin: "They fit a woman like a second skin." James Galanos: "They last forever." Lynn Manulis: "Every single sequin sewn by hand, every one, on pure silk jersey." What did they mean to Norman? Spangles (he never called them sequins) equaled theater, and theater was "the nuts," meaning the best. How did he want them to fit? Lyn Revson recalls a fitting that was her first experience of Norell's salty way of speaking: "Take it in two inches under the butt."

Perhaps the most important piece of Norellia is the Kees Van Dongen. Norell's pride and joy, it is a painting he bought at Parke-Bernet in the 40s for $125, a portrait of the Marquise Cassati walking along a canal in Venice, a gondolier nearby, surreal on a wave. Her skin is so white it's almost green; her eyes are like bruises, her dress a flapper's chemise. Everyone who knew Norman knew the painting, not only because he'd sometimes hang it in the salon for openings, but also because his collection for fall 1960—his first as Norman Norell, Inc.—seemed to step right out of it, and became known as "the Van Dongen Collection."

"He sent the girls out with all this slick black hair, these searing eyes, this white skin," Lynn Manulis recalls. "The attitude of those girls with those clothes—the audience was spellbound." Yvonne Presser, who modeled in the show, says, "It was the first time he had total freedom, almost like he'd been set free from a cage. Mr. Norell was very inspired by those years when Van Dongen was painting." Those years were the 1920s, for Norell, fashion's finest hour. With regrets to Sassoon and Courreges, here was the first flapper flash of 60s mod. Norman Norell, fall 1960!

But Norell didn't buy into the youthquake, did not do 60s kooky. "I can't make clothes the way the young people do, because I know too much," he explained. He had his backers (Prewitt Semmes of Detroit, Daniel Dietrich of Philadelphia); he had his name on the label. He would spend his 60s refining, simplifying. A son of Seventh Avenue, not Roland Barthes, Norell was unwilling to go for faux effects. While Saint Laurent might turn a dress into an abstraction by Mondrian, the only sleight of hand you got from Norell was the death-defying roll of a Norell collar, the operabox security of a Norell sleeve. "Blown on" is the way designer Isaac Mizrahi describes Norell patch pockets, which could take a day to make and sew on. "Balance" is the way Rose Simon, senior lecturer at the Fashion Institute of Technology, describes Norell tailoring. "Every part of the garment was on such a perfect grain that it fell on the body ideally. You felt graceful in it—psychologically happy and helped. You were free."

"Norell made American designers into gods" says John Fairchild.

A Norell collection contained only three to five new shapes or "bodies," but in infinite variations. "Do you know what kind of creator it takes," Ann Keagy, then chair of Parsons Fashion Design department, once asked, "to take five ideas and do 200 pieces in coloration, combination?"

And the shapes themselves? Though Norell, to the end, began collections by spending hours in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the New York Public Library, he made no secret of his continued respect for both Chanel and Balenciaga. In Norell of the 60s you feel Chanel's swingy ease shoulder to shoulder with Balenciaga's stoic seamsmanship. So there was still Parisian lineage. But there was also Anything Goes, the boat home, flags flying. It was the decade of Norell nautical suits and anchor insignia, sailor dresses and sailor gowns. (Lyn Revson was famous for wearing one in white organdysailor as angel.) There was Optimismsilhouettes of childlike directness. Norell took teasing from fellow designers for finding so much to copy in children's clothes, their caped coats, Peter Pan collars, buttons in lines of two like Madeline at school. (He worked a ratio of innocence to experience worthy of William Blake.) And there was Arrival—New World rising with its glittering cities; new money finding its place in the footlight parade; New York. A Norell by day was a Cadillac Coupe de Ville; by night, the Chrysler Building. Old-world aristocrats and robber-baron aspirees wore Balenciaga and Mainbocher, but in America the wives of the captains of industry wore Norell. "Husbands loved his clothes," says Gus Tassell, the man who was designer at Norman Norell for the four years it continued after Norell's death. "He made their women look beautiful. And rich."

Norman Norell was the Seventh Avenue success story, as esteemed in the ateliers of Paris as in the dreams of women on the social climb. That Diana Vreeland, Vogue editor and empress of fashion in the 60s—a woman devoted to Paris couture, and usually absent from Seventh Avenue—attended Norell's nine P.M. openings is no small symbol of his importance. She gave him splashy, full-color coverage in Vogue, and was a friend and admirer of 30 years. For the younger Grace Mirabella, who would succeed Vreeland as editor of Vogue, Norell was symbolic in a different way. "What the women who shop in my market want is quite simple," she once explained in exasperation. "They want us to tell them what Norman Norell wants them to wear."

Primus inter pares: that's how the late maestro Erich Leinsdorf once referred to the role of an orchestra conductor—"first among peers"—and it's not a bad way to think about Norman Norell at that time. (When Pierre Berge met Norell in 1965, he said, "He looks like a symphony-orchestra director, that hair, that profile.") Norell, certainly racked up the firsts: first Coty American Fashion Critics' Award in 1943, first Coty Award Hall of Fame in 1958 (meaning he'd won three times), first president of the Council of Fashion Designers of America in 1965. Even the first fund-raiser for the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute, in 1963, was put over as a "party for Norman."

The name Norell was instant authority. "You don't know what an icon and a hero he was," says Carrie Donovan. "I got some of my first jobs designing because the market knew I knew Norell."

"He was somebody enormously to be respected," says designer and writer John Weitz.

"I never called him Norman. I f called him Mr. Norell."

"He would not ever make a concession where a principle of his was involved," states Max Bernegger, Norell's business manager from 1963 to 1969. "For that he would fight like a tiger."

Yet "he was very, very kind," says Bernadine Morris, former New York Times fashion critic and author of the chapter on Norell in the 1975 book American Fashion.

"I think he set a tone that other people tried to follow," says fashion grande dame Eleanor Lambert, also from Indiana and a friend who worked closely with Norell on the Council of Fashion Designers of America and numerous other industry organizations. "Instead of going the other way like Halston—Halston sort of debauched everybody because he loved nightlife and all that—Norman was the most discreet man. I've never known such gentlemanly behavior. He had great dignity. He would have been horrified by Halston and the others—by the showiness of their lives." But there was a private life.

The story of Norman Norell has always been told with the love life missing. It's sometimes told as if there were no social life at all. True, designers then didn't "climb." Norell worked in an era when the unwritten rule was "Seventh and Fifth don't mix"—to be a fashion designer was practically a faux pas. Mainbocher might take cocktails with his clients, but he'd set up shop in Paris, not in Manhattan's garment district. Norell preferred New York. ("In Paris I don't think I'd work as hard," he said. "You've got to fight to make something beautiful here.") He had no interest in the social whirl, used his "shyness" to stay behind the scenes, was blunt about star ladies ("Never expect anything but grief'), and was happiest lunching with the Kids, whom he doted on like daughters and who loved him like a father. Dinner out—Schrafft's, Hamburger Heaven, Le Pavilion, or La Grenouille—and the best seats at the theater were the extent of his evenings on the town. Norell was a man who lived for work, though he did not always live alone.

A Norell by day was a Cadillac Coupe de Ville; by night, the Chrysler Building.

There were three relationships. The first was the deepest, but also the least known because it went farthest back. That man was Alan Arthur, a very handsome, well-brought-up, well-read pianist from Connecticut. Norell was devoted to Arthur, and they lived together for 20 years, from the 1920s to the early 40s, with Norell handing over his paychecks and Arthur managing the household. (He's the one who pushed Norell to approach Hattie Carnegie for a job.) Arthur had great taste, extravagant taste—he'd buy 12 dozen embroidered linen handkerchiefs at a pop. He also had a taste for liquor. This chapter in Norell's life closes in one sad sentence: Arthur lost his looks with age, suddenly found that Norell was important while he himself had achieved nothing, and died of alcoholism in his early 40s. It was with Arthur in mind that Norell spent weekends during World War II doing volunteer work at a hospital. It was Arthur's grave in Connecticut that Norell visited every Memorial Day.

"Alan Arthur, that was the one he loved with heart and soul," maintains Alan Graham, who was a young designer when he met Norell around 1943 and became his next close companion. "Norman's crush on me was more of a continuation of Alan Arthur. He said, 'What is your first name?' And I said 'Alan.' And he said, 'A-L-A-N?' And I said, 'A-Lr-A-N,' and he was absolutely still." Graham and Norell lived together for a few years in the 1940s, but unlike Arthur, Graham was always after Norell to forgo the latest bargain at Parke-Bernet (his passions: 18th-century French furniture, solid-colored Chinese porcelain) and instead pay his taxes. Extravagance "was Norman's idea of funny," says Graham, who settled in Paris in the late 40s. "My biggest fight with Norman was another thing about taxes. Jean Schlumberger had made a lighter that was one of those flexible goldfish, so well balanced. Norman said, 'I want you to have it, he's made me a special price.' I said, 'Give the $800—you can add a zero to it today, or two—to the income-tax bureau,' and I walked out. Norman was furious, so the first thing he gave to John Moore was that lighter."

John Moore. They never lived together, but he was Norell's third love, a 20year relationship everyone knew best because it was the last. In some ways Moore was Norell's greatest extravagance.

"John met Norman as a student at Parsons," around 1950, when Moore was 22, says the illustrator Hilary Knight, who came to know Norell through Moore. "John was very ambitious. He wanted to be glamorous. And here was this wonderful, handsome, rich, successful man. And they hit it off. They both truly loved the fashion business. And both had a mischievous sense of humor." Moore not only accepted the articulated goldfish lighter, he flaunted it.

The problem was—that old refrain— Moore drank. He flaunted that too. Fellow designers remember him as a holy terror, throwing drinks at cocktail parties, throwing plates at dinner. He was charming and childish, beautiful (pink and blond) and blotto. Norell had seen the results of drinking once before. Why didn't he stop Moore?

"Everybody else worshiped Norell," says Bemadine Morris, "and I think there was a need for him to find bad boys." A close friend says, "He felt if he was too strong he might lose John. And John was his private life." He then concurs with what others have said: "Norman had a little streak of masochism in him. And John had a streak of sadism. I don't mean that came out physically. Never. Norman had nothing to prove. He was at the top of his profession and could afford to be beaten down. And John would do it."

Max Bernegger has a different perspective on the dynamic. "Norman's biggest problem was that if he liked somebody very much, or loved a person, he had a tremendous tendency to control. And that could be very destructive. He was controlling John. And John became dependent upon him almost, and suffered because of it."

"Absolutely true," agrees Alan Graham. "Yes, Norman was very kind and thoughtful. And he was extremely generous—to a fault. That didn't stop him from being a perfect bitch in his private life."

In 1963, Norell helped back Moore in his own business, a big responsibility that should have cut into the young man's benders, but didn't. Moore had successes, most notably in 1965 when he designed Lady Bird Johnson's yellow satin inaugural gown. But then, says Carrie Donovan, "John began to make these convoluted, draped, very strange costumes." Norman's support remained unconditional, absolute, and Moore became a blind spot professionally—which hurt them both.

"Norman interfered in ways that were meant to be helpful to John," says Hilary Knight, "and worked the reverse." Case in point: Norell's belief that Moore had a Coty award coming. In 1963, when the superhot Rudi Gemreich won, Norell expressed disapproval (unspoken unhappiness at Moore's not winning) by returning his own Hall of Fame award to Eleanor Lambert. In 1964, when the brilliant young Geoffrey Beene won, Norell remained grudging on John's behalf. In 1965, Women's Wear Daily forecast a win for Moore. So it was insult to injury when nobody won that year. Asked for his opinion, Norell said, "No comment."

Moore, drinking heavily, would close his company in 1970, taking work with another Seventh Avenue firm. He never did win that elusive best-designer Coty. And he did not receive the $40,000-a-year stipend left to him in Norell's will. (The company didn't have the profit and folded in 1976.) When Moore died last year in Alice, Texas, he was running an antiques shop. In a scrapbook found in his apartment, there are telegrams from Norell to Moore, dated late in the relationship. They are signed "ILY ILY ILY"-I love you.

Photographs of Norell up through 1961 invariably feature a cigarette held louchely between two fingers or hanging from his mouth. One day in 1961, after months with a sore throat, visits to a doctor who found nothing, and nagging from Moore, he went to a specialist and heard the words "Mr. Norell, you have smoked your last cigarette." Norman had throat cancer.

As he himself told the story, he didn't go back to his office, but straight home to his apartment, where the first person he told was his houseboy. "I've just been to the doctor and he tells me I have cancer of the throat and of course I'll never be able to smoke again." The houseboy looked at him in horror and said, "Oh, Mr. Norell, and I've just bought you a whole new carton."

Norell stood up to the illness. Lynn Manulis tells of how just months after his surgery she asked Norell and his models to put on a fashion show for a cancer benefit in Palm Beach, the first of its kind. (Bob Hope would be the M.C., .and for the opener, a young unknown named Barbra Streisand.) Norell could not speak yet—his surgeon, Dr. John Conley, had rebuilt his voice box with tissue from his thigh—but he nodded yes. "He showed 80 pieces in less than 15 minutes," Manulis says. "It was like fast movies. At the end, the whole audience of 2,200 people was standing."

But that was only the overture. Something silent, private, occurred the next day, when a woman well known in Palm Beach and in the country called the store. Manulis speaks carefully. "She had recently undergone a mastectomy, and she was absolutely destroyed. She loved clothes, she wore Norell's clothes for years. She said, 'I would like to come and have a private appointment with Mr. Norell.' " The woman arrived in slacks and a simple white blouse, and waited nervously in the dressing room. When he walked into the room, Manulis recalls, the woman said, "'Norman, look what they've done to me,' and pulled open the blouse. He had a pad and pencil in his hand because he could not speak. He looked for a brief moment at this scene, and he took his pad and he wrote these words—I'll never forget—'We are the lucky ones. We have survived.'"

Inside the story of Norman Norell lies the beginning of another fashion story, that of John Burr Fairchild, the newspaperman who turned 70 this year and is now editor-at-large of WWD and W. Bom only a year before John Moore, this John became the new publisher of Women ⅛ Wear Daily in 1960.

In the early 60s, Norell was the name, Fairchild the new kid. Norell was worldclass, WWD backyard, a boring rag-trade paper. Women's Wear began to throw its little light on big Norell in early 1962, calling his spring '62 silhouette "the strongest—and most flattering—since Christian Dior's postwar New Look." The friendship was forged months later when Norell, unhappy that The New York Times had dispatched a (negative) review before his show was even over, banned the Times from his fashion shows—just the kind of "stinkerooni" (John Weitz's word) Fairchild loved. Women's Wear gave Norell its spotlight, and, not surprisingly, its spotlight grew.

While the Times had called Norell, understatedly, "America's No. 1 designer," in Women's Wear he was the Great Norell, one of four big-name creators (with Chanel, Balenciaga, and Saint Laurent). There were rave reviews, spreads galore. There was Norman chatting, Norman cheerleading for Seventh Avenue, Norman critiquing Seventh Avenue. It was heady stuff. Headswelling stuff. "Norman shouldn't have been buttered up by John Fairchild, because Norman was no sucker," says Alan Graham. "But that's what happens with age." And it was head-game stuff, too. Everybody knew Fairchild's priority was Paris couture. This was the man who told his colleague James Brady, regarding American ready-to-wear designers, "Show your disdain for them, they're no good anyway." ("That's not an accurate quote," responds Fairchild. "And the predominance of Paris was obvious.") Fairchild respected Norell: "He was the one who made American designers into gods." He also needed Norell. And not just as a subject.

"Let me explain," says Bemadine Morris, who worked at Women's Wear in the early 60s. "Norman started his own business in 1960. John Fairchild came back from Paris to take over WWD in 1960— to build a new kind of Women's Wear. So it coincided. John knew Norman because Norman would go to Paris to buy fabrics. John would tell other designers on Seventh Avenue, 'If you don't let me have sketches in advance I will fill up the paper with Norman Norell,' meaning Norman was top-of-the-line. He'd fill his paper up with Norman Norell and French designers. It was one of the things that made an impact." "I don't think I said that," Fairchild recalls. "But I was really determined to have the sketches before anybody else."

If no American designer in the 60s had the profile in WWD that Norell did, no American designer was dropped with such a sneer. The worm turned in 1967. Sift the review of Norell's spring collection and you see signs: there's a slap at the Kids ("Norman's mannequins of a certain age"), a reference to Norell as "the Fallen Angel," and bestowal of the title "Old Master," which Fairchild had coined earlier for Balenciaga and would soon inflate to Grand Old Master, or G.O.M., for Norell. It was a mock curtsy a la Iago.

The "why" is moot. In fallouts with Fairchild there are many explanations and there are none. Max Bernegger brings it down to business: "Norell did not want to have pictures publicized of his fashion shows, because he got knocked off. The stores were very upset about that, too. Norman made me tell Fairchild that he could not publicize pictures of the show. So in the next issue that Fairchild did, he blurred the pictures so you couldn't see the details, but Norell was upset about that also. So the next time Fairchild put in pictures, there were X's through them, like it's bad stuff. John, as nice as he can be, can also be very, very nasty."

The coup de grace came on February 8, 1967. On its front page WWD called James Galanos "the leader of American fashion," implicitly demoting Norell (and playing friends against each other). An X made of white adhesive tape went up on Norell's portrait in the offices of Women's Wear. It was Rise and Fall at WWD.

Except there was no Fall. Retailers were as devoted to Norell as ever. Many knew nothing of the freeze with Fairchild, or, if they did know, couldn't have cared less. Besides, bigger things were brewing. Understanding that the company was sitting on a name with legs—and that no American designer had ever done a fragrance—Bernegger got permission from Norell to approach Revlon founder and chairman Charles Revson about a perfume deal. Revson was interested. And when he asked his wife, Lyn, what she wanted for Christmas, and she replied, "A perfume for Norman," it was all systems go.

In 1968, while the other "Old Master," Balenciaga, was retiring, Norell was reaching designer Nirvana, a place you get to not through clothes but through the nose. Norell perfume was launched with a bash at Bonwit Teller. A year and a half of mixing and wrist sniffing had produced a scent with a bite—a sharp shock of green that softened into a lily note. Billed as "the First Great Perfume Bom in America," it was yet another first for Norell.

"That theme was a good one, strong and audacious and legal to say," explains Paul Woolard, vice president of Revlon at that time, and the man who oversaw the development of Norell perfume. "Revlon changed the fragrance business dramatically in terms of concentration, and it began with Norell, which had a much larger concentration of fragrance oil, at least double. It lasted very well. Norell's clothes lasted well. So it all fit in."

And it took off immediately. "Like a house afire," remembers Edna Sullivan, the woman who ran Norell's salon. "We like to make money at Revlon," says Woolard. "It was profitable from the start."

With die perfume came powerful brandname identity. Norell, so long sequestered in hushed, upper-floor salons, was now on first floors, where Norell perfume was a splurge within almost anyone's reach. The perfume bottle was a stunner—cut crystal, heavy, like the ashtray Woolard had seen on Norell's desk. In fact, its rectangular shape is the same shape as a dress label. It wore only one word—norell—stretched tall to fill the entire side of the bottle. "Norman is the one who said, 'Double the height,'" Woolard reveals. On the box, black against white, those letters look like a row of New York City skyscrapers. On the bottle, black against the goldenhued perfume, they suggest elegant afternoon shadows lengthening into night.

With the perfume came self-possession— a lifelong dream realized. Norell was now 71. Worried about the changing economy and how it was affecting the sale of luxury goods, concerned about his own financial security, as well as Moore's, Norell called Bemegger, who suggested they offer the royalties and rights of Norell perfume back to Revlon. The early 70s were the beginning of the boom in licensing, a boom Norell had no interest in (all he ever wanted was to oversee his own business, pattern by pattern, dress by dress), and Revlon was pleased to make the deal—$1,247 million. With this money, Norell, who'd owned a mere 15 percent of his business, bought out partners Semmes and Dietrich. In March of 1972, Woolard states, "Norman became a free man."

"He had not owned his own name and it concerned his pride," explains Dr. Kevin Cahill, Norman's close friend and physician. "The perfume was important in terms of making him independent—and his joy in that,"

'They usually do retrospectives when you're dead." That's what Norman said to Denise Duldner, two days before the 50-year Norell retrospective fashion show, to be held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Monday, October 16, 1972. It was the brainchild of Parsons's Ann Keagy, a gala evening a year in the planning—both a celebration of Norell and a way to thank him for 20 years of dedicated teaching at Parsons. (Even while he was being treated for cancer, he never missed a class.) Women from all over the country—including Lauren Bacall, socialite Hope Hampton (who bought a mermaid a year), Lady Bird Johnson, Babe Paley, Martha Phillips, Lyn Revson, and Dinah Shore— were lending Norells from the 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s. Afterward, dinner at La Cote Basque.

Everyone recalls how caught up in the show Norell was, which wasn't unusual. "He was a perfectionist," says Duldner. "He'd get very consumed." But there were other anxieties. John Moore was drinking badly, getting belligerent with Norell, and threatening a scene at the retrospective (a measure, perhaps, of just how small Moore was feeling). Also, Time's winged chariot was hovering close. No matter that Norell's last collection, fall 1972, had been one of his best. (In the Times, Bemadine Morris compared its wintery simplicity to late Matisse.) The industry was changing fast, loosening its seams. Even Balenciaga went and died that year. The retrospective would be a summation and Norell wanted it right. "His craft was very important to him," Duldner recounts. "He didn't want to be called old hat."

All day Saturday, the 72-year-old designer was moving big boxes in the storeroom, looking for shoes to match some mermaids. On Sunday morning he made at least two phone calls, one to Kevin Cahill and one to Lyn Revson, both alarming. There was slurred speech, long silence. When the super finally got into Norell's Amster Yard apartment, he was found unconscious ... a stroke.

Norell never came to. It is said he gave the go-ahead for the show—which went on—by squeezing someone's hand, though this may be a spangle "sewn on by hand." For 10 days the lobby at Lenox Hill Hospital was a second, silent Le Cirque to the ladies who loved him. Norell suffered another stroke and died on October 25.

Twenty-five years later, the church service is still described as beautiful. White lilies, Psalm 121, the cabine in the front row wearing shades of gray, ivory, beige— the last collection! The music was Moore's idea and a touch Norell would have adored: Bobby Short at a baby grand playing Cole Porter, Noel Coward, and a love song from Lady in the Dark called "My Ship." One of Norell's favorites, the song begins, "My ship has sails that are made of silk." It's Norman Norell's life in a single line—mermaids glittering, watchful, then gone.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now