Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

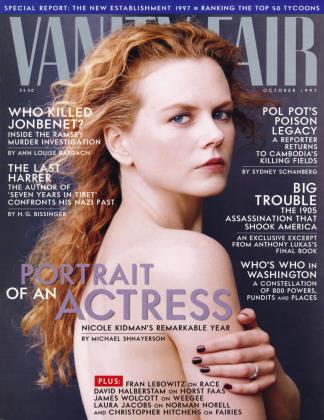

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBAD TROUBLE IN THE BIG WEST

Books

In 1905, when Idaho's former governor was blown up in front of his mansion, the killing ignited the American West, fueling a vicious labor war, heightening the bitter rivalry between two giant detective agencies, Pinkerton and Thiel, and setting the stage for one of the country's first celebrity murder trials

J. ANTHONY LUKAS

"Caldwell is a straight business proposition. It is a cold-blooded moneymaking proposition. Your health will improve in Caldwell with the swelling of your assets, and salvation comes easier with prosperity. "

—From the Caldwell Tribune, 1893.

It began to snow just before dawn, chalky flakes tumbling through the hush of the sleeping town, quilting the pastures, tracing fence rails and porch posts along the dusky lanes. In the livery stables that lined Indian Creek, dray horses and fancy pacers, shifting in their stalls, nickered into the pale light. Off to the east, behind the whitening knob of Squaw Butte, rose the wail of the Union Pacific's morning train from Boise, due into the Caldwell depot at 6:35.

Excerpted fromBig Trouble, by J. Anthony Lukas, to be published this month by Simon & Schuster; © 1997 by the author.

Sounding into Caldwell's jaunty new development in Washington Heights on that final Saturday of 1905, the whistle brought an unwelcome summons to Frank Steunenberg. The former governor of Idaho lay abed in his family's eccentric gray-and-white edifice, a hybrid of Queen Anne and American Colonial styles, bristling with gables, porches, columns, and chimneys.

The governor—as he was still known, five years out of office—had thrashed all night. So he hauled himself up and put on his favorite six-dollar shirt, with its flowered design.

"The good and evil spirits were calling me all night long," he told his wife before burying his face in his hands.

"Please do not resist the good spirits, Papa," Belle admonished, persuading her husband, who generally eschewed such rituals, to kneel and join her at the Scriptures.

Belle, a bit severe behind her spectacles, had "bundled up" and left for a time after her husband killed a fourth bull snake in the kitchen. A devout Seventh-Day Adventist, she had adopted the bleak ascetism of Ellen G. White, who likened each person's "vital force" to a bank account depleted by every withdrawal. Fearful of such diminishment, Belle largely abstained from conjugal relations.

After feeding his stock with the help of his English bulldog, Jumbo, the husky 44-year-old Steunenberg sat down with the children—Julian, 19, on Christmas vacation from college; Frances, 13; Frank junior, 5; and eight-month-old Edna, an orphan the family had adopted that year. Their hired girl, Rose Flora, served up a breakfast of wheat cereal, stewed fruit, perhaps an unbuttered slice of oatmeal bread.

If the governor had allowed his melancholy to infect the morning, it would have been out of character. With his children, he was puckish and full of sly doggerel. For his daughter he once composed: "Frances had a little watch / She swallowed it one day / Her mother gave her castor oil / To help her pass the time away."

Breakfast was followed by a phone call from A. K. Steunenberg, one of the governor's five brothers. A.K. served as cashier of the Caldwell Banking and Trust Company, of which Frank was president. A business associate, he said, wanted to meet the brothers. But Frank declined; he wasn't in the right frame of mind. The governor's disinclination to do business that day would later be much remarked upon.

Toward noon, young Theodore Bird, a representative of the New York Life Insurance Company, arrived from the capital to renew the governor's $4,500 life-insurance policy, which expired at year's end, barely 36 hours hence. Frank agreed to meet him later.

Most of the morning, as wind-driven snow hissed, the governor read and wrote. At four o'clock he put on his overcoat and a slouch hat, avoiding a tie: some said the aversion came from the governor's youth, when he was too indigent to afford such doohickeys. He just buttoned his shirt around his neck, leaving the uncovered brass collar button to glint like a gold coin at his throat. One bemused Wall Streeter remembered him as "a rugged giant who wore a bearskin coat flapping over a collarless shirt."

Bundled a bit awkwardly, the governor set off down Cleveland Boulevard, wondering at the transformation wrought in scarcely two decades. In 1887, fresh from the black loam of his native Iowa, he'd been dismayed by the alkali desert. He wrote to his father, of "land that ... is 'death' on shoe leather."

On December 9, 1883—when Caldwell was only canvas tents and frame shacks strewn along a dusty track, the first issue of the Caldwell Tribune dubbed it the Magic City. Like other booster papers across the West, the weekly Tribune "sometimes represented things that had not yet gone through the formality of taking place."

Now Caldwell was booming. Over five years, it had added electric power (the generators ran dusk to midnight), two phone companies, a waterworks, Idaho's first public park, a county fairgrounds, flour mill, creamery, hotel, and several dozen stores. A new City Hall was rising, too.

In their rampant boosterism, Caldwell's promoters appealed to the naked self -interest of settlers. "The spirit of the times, which we called the spirit of progress," wrote Kansas editor William Allen White, "was a greedy endeavor."

As dusk gathered, the governor slogged through ankle-deep snow and eyed the symbols of prosperity surrounding him. Some 80 feet in breadth, Cleveland Boulevard was lined for two miles with western-Colonial or bungalow-style

houses—rustic, rangy dwellings with graceful porch posts, bits of colored glass in door panels, dormer windows, and spacious verandas, for summer evenings amid the thrum of cicadas.

The turreted Queen Anne mansion of the governor's old friend John C. Rice, a lantern-jawed lawyer, was similar to dwellings rising in San Francisco and Chicago, and provided no fewer than four porches. Like the Steunenberg mansion, it was an outpost of gentility in a parvenu neighborhood that was home to no less than three saloonkeepers: Dan Brown, who ran the Caldwell Club, where he kept two bear cubs chained to a telephone pole; Perry Groves, co-owner of the Palace, which touted its fresh oysters and hot tamales; and Rasmus Christenson, whose Board of Trade saloon offered "clubrooms and pool tables." Christenson doubled as agent for Kellogg's Old Bourbon, one of the West's most popular brands.

Plunging into the storm, the governor managed to keep his footing on the icy boardwalk. Cement sidewalks were still rare in Caldwell, and in summer the powdery dust rose in choking billows. The municipal sprinkler wagon, with its driver dozing under his yellow umbrella, dutifully laid down a fine spray of water on each baking street twice a day.

Automobiles—"buzz carts" or "devil wagons"—had already appeared in Caldwell, among them a big black beauty belonging to the cashier of the First National Bank, and a sporty roadster belonging to Walter Sebree of the power company. But the roads were so bad that it took almost three hours to drive the 29 miles from Boise.

If the town still battled dust and mud, at least it had beaten back the damned desert. Irrigation had turned the landscape from ghostly white to vivid green. Alfalfa, timothy, clover, sugar beets, apples, peaches, and pears all flourished. In 1890 alone, Caldwell had planted more than 4,000 trees: sagebrush and greasewood gave way to cottonwoods, box elders, Lombardy poplars and catalpas, black willows and elms. Nobody was more thrilled than Frank Steunenberg.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 269

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 262

On a train trip in 1904, gazing at the dense woodlands of southern Indiana, he had written: "I never tire of looking at the graceful trees, now covering an adjacent hillside and again gracing a distant ridge with glory and grandeur. . . . Oh, the happy days of my boyhood amid the trees."

A weather vane in the shape of a great Percheron horse stood high for years atop one of Caldwell's stables. It was an appropriate symbol for a town where the bouquet of fresh manure hovered like the morning fogs that clung to the mud-slick roadways. (Some Cassandras believed that the practice of kicking piles of manure directly into Indian Creek might explain the raging typhoid epidemic.)

Livery was the town's principal industry: drummers rented rigs, fancy buggies, ladies' landaus, and arabesque sleighs, and the stables harbored vehicles from hackney coach to funeral hearse.

County. "Conditions in Idaho," he warned in a press interview, "are bad enough to make anarchists of nearly everybody." Judge Frank J. Smith of the Seventh Judicial District, which included Caldwell, feared that the railroads' clout could only stir deep unrest in Canyon

Yet when people said, "I'm going to the railroad," they meant Caldwell. The iron horse had made the town. The Oregon Short Line was so overburdened with freight and traffic that some businessmen thought of chipping in and hiring a man "to help the boys at the depot." That didn't mean the Short Line and its parent, the Union Pacific, were beloved institutions. Indeed, the "railrogues" were Idahoans' favorite objects of derision. Not so many years before, Populists had orated from a wagon near the Odd Fellows Hall in the light of a great bonfire made of railroad ties from "the great monopoly Union Pacific." In his 1901 polemic, The Octopus, muckraker Frank Norris had depicted the iron horse as the "galloping monster, the terror of steel and steam, with its single eye, Cyclopean."

Merchants, farmers, and mine operators alike seethed at the freight rates— which they considered extortionate—as well as at the railroads' practice of heavy rebates to the biggest shippers, like Standard Oil and Armour, which only drove rates up for smaller customers.

Picking his way through the manure-pocked, new-fallen snow, the governor hurried past C. E. Barnes's grocery, and signs offering candied orange peel and raisins. Reaching Main Street, he spied the familiar brick pressroom of the Tribune.

The future governor had published a small-town Iowa newspaper before A.K. bought the moribund Tribune and sent for help. By the time Frank and Belle arrived in Idaho on January 9, 1887, A.K. had published his first issue. "We are here for the money," he wrote, "because this country is going to go boom and we want to boom with it."

A.K., one of Caldwell's 45 randy bachelors, launched a column called "The Marriage Bureau," and invited ladies to write to "any name which may tickle their fancy." One addressed bachelor Orville Baker: "What's in a name? It's a man I want, and am perfectly willing to look over any minor issues. Do you mean biz? If so, say so and we'll hitch. I'm a gushing girl of 35 very short summers; your age is immaterial. . . . Yours for Business. Gushing Ann."

When Caldwell opened Idaho's first athletic club in 1891, its 40 members were "young and full of blood." ("They leaped into life like the boys they still were," A.K.'s daughter, Bess, recalled.) But marriage and children had inspired creeping respectability. Just days before Christmas, 267 residents had prayed for the city council to pass an ordinance closing the saloons on Sunday. The governor's wife and his sister Lizzie were charter members of their Idaho State men's Christian Temperance Union chapter, which held receptions at the Steunenberg residence.

At the corner of Kimball and Main, the governor turned north up Main Street, past Ah Kim's, one of the four Asian restaurants where the residents of Caldwell relished chop sueys and egg foo yungs.

Children bought firecrackers from the pigtailed Asian who ran a laundry on Main Street, and women purchased vegetables from wizened China Jim's wagon. But people weren't pleased with 88-year-old Guy Lee, who was said to be running an opium den, and weren't entirely comfortable with the influx of Chinese workers to the lower end of town.

Many of the Chinese were former railroad workers now digging Canyon County's irrigation ditches. Thousands of "coolies" had been brought into the Idaho Territory to lay track for the Union Pacific. By 1870 they had dispersed to the mining camps, and the territory had the largest concentration of Chinese in the trans-Mississippi West outside California.

Tolerated by the earliest pioneers, they were not welcomed by the white miners. By 1900 the Chinese foothold in Idaho had shrunk to 1,467. In 1904, when a lone Chinese man disembarked from a stagecoach in Twin Falls, 180 miles down the Snake River from Caldwell, a citizens' committee gave the "venturesome Celestial" the best meal the town afforded, then took him to the ferry and told him to "hit the breeze" for Shoshone.

Caldwell wasn't exactly partial to Jews, Negroes, Italians, Indians, or Basques either. The one Jewish merchant-clothier Isidor Mayer—was something of a curiosity. One Halloween he found his shop door blocked by a huge boulder.

No Negroes lived in town (in 1900, a scant 293 could be found in the entire state), and some young folk had never seen one, save for McKanlam's Colored Vaudeville troupe, which played Isham's Opera House once a year.

Caldwell's opera house was a modest theater, with rows of benches toward the back, lines of kitchen chairs, a few proper theater seats (35 cents if reserved in advance), and, flanking the stage, boxes draped in velour. It was a regular stop for vaudevillians, blackfaceminstrel shows, and itinerant culture on the Chautauqua lecture circuit, as well as traveling theatrical companies. On December 27, the place had been packed for the Great McEwan, a hypnotist and prestidigitator. Two other recent visitors, midgets known as the Lilliputian Sisters, offered Caldwell an "amusing, elevating and refining" evening of duets, dialogues, and posings.

The governor attended the theater every chance he got. A passionate fan of the dramatic arts, he preferred "those entertainments that pictured the lighter side of life," and that drew great guffaws from his substantial belly.

Across the street from Isham's, the Caldwell Banking and Trust Company was a graceful structure erected the previous year by Frank and A.K. at a cost of $20,000. Seeking something distinctive in the "commercial style," the Steunenbergs had turned to Idaho's pre-eminent architects, J. E. Tourtellotte and Company of Boise, who designed hallways lined with polished oak wainscoting. Frank's spacious corner office was bathed in light from five arched windows.

Theodore Bird, the agent whom the governor had agreed to meet at the bank, represented the nation's largest insurance company. New York Life had been active in Idaho for four decades, paying its first death claim there in 1865. In 1895, it had established an elite rank of agents called Nylics. At company conventions, cheerleaders sang "the Nylic Song."

If, after the departure of the insurance man, Frank Steunenberg had rested his feet on the big oak partners deskon which he liked to whittle with a favorite penknife—and gazed out his wide windows, he could have reflected on the solvency of his banking, real-estate, and commercial enterprises. Altogether, the governor was worth more than $55,000—equivalent to around $325,000 in 1997 dollars. It was an impressive figure for a man who had come west 18 years before with only a few hundred dollars, and who earned only $3,000 a year during his four years as governor.

Yet prosperity hadn't brought him peace of mind. The sepia photographs and other memorabilia of his gubernatorial years that covered his office walls never failed to stir a sense of loss, even bereavement.

The Caldwell Club had bear cubs; the Palace touted its oysters and hot tamales; at the Board of Trade, Kellogg's Old Bourbon was favored.

Frank, a Democrat from a Republican family, couldn't escape the feeling that high office had been snatched away from him unjustly, that he'd been blamed unfairly for mishandling labor unrest in the state's northern panhandle.

He dreamed of running for the Senate, and his frequent trips around the state, to his sheep ranches, banks, and irrigation projects, were convenient excuses to get back in touch with his supporters. On a recent election day, when talking of politics, Steunenberg had exclaimed: "Oh, I love it! It's a great game, and I would rather play than do anything."

As the governor left his office at about five o'clock, he paused in the blowing snow to cast a proprietary glance at his family's latest venture: the half-sunk foundation of a matching office building, to be called the Steunenberg Block, which would soon rise beside the bank. Three broad-shouldered emporiums would elbow one another at street level, with offices on the floor above. The name Steunenberg would be carved in a rectangular stone above the second-story windows. The governor could be pardoned if he relished the notion of future generations seeing his name chiseled there in stone, impervious to wind, storm, and the passage of time.

As Frank Steunenberg crossed Seventh Avenue, he approached the palecream facade of the Saratoga Hotel, built in the French-chateau style with a mansard roof, corner turrets, a Palladian window, and bay windows. From its arched doorway, a broad corridor led to a rotunda, where tables provided blackjack, faro, and roulette.

Just before six every Saturday the governor crossed the Saratoga's threshold to pick a Tribune from the stack of papers on the gift-shop counter. Press time was five P.M., so the copies were barely an hour old. How he loved their inky smell.

Sinking into a creaking leather chair by the hearth in the Saratoga barroom, Caldwell's first citizen may have ordered a cup of the hotel's mulled cider— strictly nonalcoholic—to dispel the blizzard's chill. Then, with a flush of satisfaction, he skimmed the week's news.

At six P.M. he set off through the darkening evening toward his own glowing hearth. As usual, he attracted his fair share of attention as he moved past the store windows still decked with illuminated balls, red and green crepe paper, and heaps of pine boughs. One amiable commentator once dubbed him "a fit subject for a portrait by Rembrandt." Another thought he had "the face of a Roman senator," not that of Marcus Antonius, but rather the slightly cockeyed visage of Popillius Laenas. A friend fondly remarked, "He didn't have so many peculiarities, but those he did have, he hugged very close."

Entering 16th Avenue, the governor saw warm light filtering through the lace curtains of his living room, where, minutes before, Belle and two of the younger children had knelt for evening prayers.

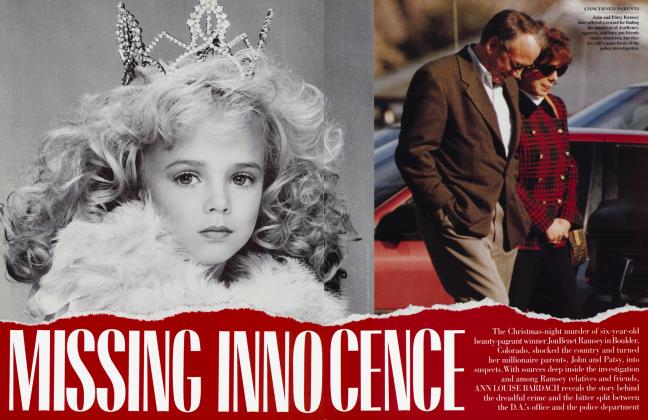

He reached down and pulled the wooden slide that opened the gate leading to his side door. As he turned to close it, an explosion split the evening calm, demolishing the gate, the eightinch-thick gatepost, and the nearby fencing, and splintering yards of boardwalk. The governor was hurled 10 feet into his yard.

Thirteen-year-old Frances, glancing out the window, watched her father fall. She was at his side in a few seconds, joined almost immediately by Belle. Mother and daughter stared in blank incomprehension at the governor, sprawled on his back, naked from the waist down, blood seeping from his mangled legs, staining the snow an ugly pink.

Across the street, the door of a modest one-story house burst open and C. F. Wayne, a nurseryman, sprinted toward Belle. "Is this Mr. Steunenberg?" he asked.

"Send for Mama," said the governor. Then he mumbled, "Who shot me? Take me inside. I'm freezing."

Wayne tried to lift him, but the injured man's limbs were "mere shreds of flesh." His favorite shirt now had a dozen holes in front.

Wayne raced out to Cleveland Boulevard, where Julian Steunenberg came running. A sturdy youth with a shock of blond hair, Julian was remarkably like his father in face and figure.

Strolling along, he had heard and felt the explosion, then dashed for home with pounding heart.

From all over Caldwell, townspeople streamed through the icy night. Eventually nearly 500 persons—fully a fourth of the town—were gathered across from the governor's house, now lit by kerosene lamps. The neighborhood's electric power had been knocked out. Windows on the north and west sides of the house had been shattered, as had those in other houses for blocks around. Shards of glass littered the floors. A large clock had toppled from its shelf, striking five-year-old Frank junior on the leather couch below. "Frank has shot himself somehow," Belle told her brother-in-law Will, upon his arrival. It was a curious conclusion for her to have seized upon.

The governor was writhing on his daughter's bed, his right arm barely connected to his shoulder, his right leg man-

gled, and both legs broken at the ankles. He kept asking to have his legs rubbed. Struggling to raise himself on his one good elbow, he spoke with eerie prescience, "I'm a dead man."

Three doctors arrived, but there was nothing they could do.

Cradling his brother in his arms, Will Steunenberg asked twice whether he'd seen anyone before the explosion, but the governor just stared up with wide, stunned eyes.

Just past 7:10 P.M., Frank Steunenberg gasped three or four times and said something unintelligible. As Will leaned closer, trying to hear those last syllables, his brother sank back and died.

Will, a shoemaker who grew indignant when anyone called him a cobbler, had always glowered at the world. Now his eyes would darken further. "Life has seemed like a never-ending nightmare since this happened," he would write. "I feel just as though I don't want to stay here anymore."

Frank Gooding, Idaho's new Republican governor, asked the Oregon Short Line for a special train to take him and his party to Caldwell. At 9:43, an engine, passenger coach, and baggage car left the Boise depot, bearing leading capital figures and volunteers brandishing squirrel rifles, broom handles, and baseball bats.

Although officials scrutinized the grounds around Steunenberg's house by lantern light, it was not until morning that the governor's party could assess the explosion's force. Drifting like specters through the mist, investigators found pieces of iron, brass, copper, and gun wadding, as well as a fragment of Frank Steunenberg's hat brim 200 yards from the gateway.

On a nearby lawn, Sheriff Angus Sutherland of Shoshone County found a dead yellowhammer, a bird with brilliant yellow and brown feathers, perfect in every particular.

One of the main searchers was Joe Hutchinson, Steunenberg's lieutenant governor, who had clambered aboard Gooding's special train. When investigators found a waxed silk fishline and part of a trigger mechanism, Hutchinson concluded that the assassin must have waited until the governor was inside the gate. Then he had pulled on the line.

A former mine foreman and explosives expert, Hutchinson recognized a distinctive odor on Frank Steunenberg's hat brim. He announced that the principal ingredient of the bomb that had killed the governor was nitroglycerin, probably in the form of dynamite.

Made with a "blasting oil" (nitroglycerin), which was developed in 1846, dynamite could be transported, stored, cut with a knife, and handled without accidents. It was ideal for this era of insurrection and assassination when European and, increasingly, American anarchists warred against capitalism. It had been widely used as a weapon of industrial warfare in the United States, notably at Haymarket Square in Chicago in 1886, where a bomb had been thrown into the ranks of policemen dispersing a workers' rally. The event became a symbol of the chaos lurking beneath the era's gilded crust.

The end of 1905 and start of 1906 was an especially nervous time. The memory of the assassination of President William McKinley remained vivid. Five days after Steunenberg's assassination, Mrs. Minor Morris—the 50year-old sister of an Ohio congressman — was seized roughly, when she demanded to see President Roosevelt about her husband's dismissal from the Army Medical Museum. Secret Service men had ripped her organdy dress. Mrs.

Morris—whom a White House memorandum described as "a woman of generous build"— kicked and tried to bite the officers, and screamed, "Do you know who I am? I am an authoress and a highborn lady!"

II

"I didn't believe one man should have so much service and another man should have none. "

—Leon Czolgosz, after murdering President William McKinley.

Floundering through snowdrifts toward his brother's deathbed, Will Steunenberg had thought, It's the Coeur d'Alenes! Within hours of Steunenberg's death, Governor Frank Gooding reached the same conclusion. Their simultaneous convergence on these "troubles" reflected the strange power of those remote episodes.

The mineral riches buried beneath the ragged peaks and sculpted valleys of the northern-Idaho panhandle had remained hidden until August 1883, when Andrew Prichard and his grizzled partner, Bill Keeler, strode to the bar of a Spokane Falls saloon, their buckskin pouches bulging with four pounds of gold nuggets and flakes. Two hundred men surged around the pair, pressing for details of the find, which had occurred on a small tributary to the North Fork of the Coeur d'Alene River. That euphoric night marked the start of the great Coeur d'Alene gold rush. Nearly 8,000 miners came, but by the time the spring sun and warm chinook winds filtered through the pine and larch forest, it was clear that most of the good diggings had already been snapped up.

In early 1884, swarms of the now resentful prospectors raced to sample the swift creeks emptying into the South Fork. They found not gold but a black substance called galena, or sulfide of lead, which was often mixed with zinc and silver. A few soon recognized its value, but knew that the impure veins of galena couldn't be exploited without capital, technology, and operations beyond the means of small companies. Into this vacuum moved heavily capitalized corporations with stockholders such as Andrew Mellon and John D. Rockefeller.

The hopeful prospectors were transformed into laborers with no hopes beyond survival.

"View their work!" wrote Eliot Lord of Nevada's Comstock mine workers. "Descending from the surface in shaftcages, they enter narrow galleries where the air is scarcely respirable. The stenches of decaying vegetable matter, hot foul water and human excretions intensify the effects of the heat. The men throw off their clothes. . . . Only a light breechcloth covers their hips, and thick soled shoes protect their feet from the scorching rocks and steaming rills of water."

By the 1860s, prompted by these difficult conditions, hard-rock miners in Nevada and California began to organize workingmen's associations. Unions reached the Coeur d'Alenes much later. In 1887, workers at the Bunker Hill and Sullivan mine formed the Wardner Miners Union, which was followed by similar units at the Gem, Burke, and Mullan mines. On New Year's Day of 1891, the four unions formed the Miners Union of the Coeur d'Alenes.

Seven weeks later, 13 mineowners founded an organization known as the Mineowners Association (MOA). By year's end, spurred by a decision of the Northern Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads to raise their rates for ores shipped to Omaha and Denver smelters, the mineowners shut down all mines under their control. Two thousand miners were out of work.

Though the railroads restored the old rates on March 15, the mineowners remained determined to reduce wages, at least for unskilled car men and shovelers. When the unionized miners struck, the owners locked them out, attempting to break the union. By June, 800 non-union miners had arrived, allowing some mines to resume operations.

Then, in early July, members of the Gem union discovered that one of its most trusted men, Charles Siringo, was an undercover employee of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, one of the huge companies which played a major role in law enforcement before the state and federal governments developed investigative capacities. The Pinkertons had become known as protectors—some said private police—of industry and often intervened in strikes.

In September 1891, as tensions built in the Coeur d'Alenes, the mine owners asked the Pinkertons to send an operative to infiltrate the union. The agency sent Siringo, a 44-year-old "cowboy detective" from southeast Texas. As a young man he'd run a combination cigar store, ice-cream parlor, and oyster bar in Caldwell, Kansas. A phrenologist who ran his hand through Siringo's hair declared, "This is a fine head for a newspaper editor, stock-raiser, or detective."

Siringo chose the latter.

By Saturday, July 9, 1892, Gem's single street was surging with angry union members brandishing rifles. Siringo was in hiding. At five A.M. on July 12, unionists in the hills above the Gem's neighboring Helena-Frisco mine began to exchange gunfire with non-union men behind the scab forts at the old four-story mill. At around nine, a charge of dynamite came hurtling down the penstock and the mill blew, killing one non-union worker. Some 60 scabs marched out under a white flag and were held prisoner in the union hall. At Gem, the gunfire killed a guard, a non-union worker, and three union men. Ultimately, 70 nonunion men surrendered.

Barely 48 hours later, Norman B. Willey, Idaho's Republican governor, ordered in six companies of Idaho's National Guard and asked President Benjamin Harrison for federal troops.

Beginning on July 15, the troops arrested some 600 union miners and sympathizers, placing them in "bull pens," wooden warehouses surrounded by 14foot stockade fences. For two months, the prisoners languished without hearings or formal charges. By September, most were released, but charges were brought against dozens of union leaders, with Siringo as principal witness.

As edited by A. K. and Frank Steunenberg, the Caldwell Tribune's, commentary on the Coeur d'Alene events was extremely cautious. As a Democrat, Frank Steunenberg might have assailed the pro-owner Republican governor. As a former union typographer, he might have rallied to support embattled labor.

He did neither.

As the 1896 campaign began, few Idahoans envisioned Steunenberg, the mild-mannered country editor, as governor. But in that year's presidential race, a Democratic Populist had risen from the Nebraska plains. At that July's Democratic convention, William Jennings Bryan mesmerized delegates with a fervent declaration: "You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold," he thundered.

Steunenberg's supporters seized on his youth and midwestern birthplace to align him with Bryan in the minds of voters. With the support of Democrats, Populists, some Republicans, and organized labor, Steunenberg defeated the G.O.P.'s David H. Budlong by the largest margin ever received by an Idaho governor. Bryan swept Idaho, but lost the nation to William McKinley. With Steunenberg as governor, the Populists and the miners' unions grew more confident.

On April 17, 1897, the Populist commissioners of Shoshone County wrote Steunenberg, asking him to disband two National Guard units widely perceived as the Bunker Hill Mining Company's private army. But after a non-union foreman of the Helena-Frisco mine was marched through the streets of Gem and fatally shot, Steunenberg declined, shattering the electoral alliance that had put him in office. In the election of 1898, the Populists detached themselves from the Steunenberg Democrats. The governor triumphed by a much narrower margin than before.

Along Canyon Creek, most mineowners gradually accommodated themselves to the Populists and the union, hiring union workers and paying all underground workers the union wage of $3.50 a day. But the Bunker Hill and Sullivan Company flatly refused to hire known union men.

The killing of Steunenberg was the first successful use of dynamite-associated with anarchism and industrial warfare-in an American assassination.

By April 1899, the miners' union concluded that the time had come to confront Bunker Hill. On April 26, some 150 unionists, many armed, forced workers away from the mine.

Early on April 29, the Northern Pacific's "down train" was about to make its seven-mile morning run when the engineer and conductor noted 250 miners, masked or armed with rifles, climbing aboard. A mile down the track, in the mining camp of Mace, a hundred more miners got on. The masked men ordered a stop at the powder house of the Helena-Frisco mine, where workers loaded 80 wooden boxes, each containing 50 pounds of dynamite.

At Gem, another 150 to 200 miners armed with rifles joined their colleagues.

At Wallace, the station platform seethed with 200 more armed miners. The masked men in the cab ordered the engineer to head for Wardner, 12 miles west. A mile from there, several hundred men from the Bunker Hill and Last Chance mines managed to squeeze aboard. When the "Dynamite Express" pulled into the Kellogg depot, which served as the railhead for Wardner's mines and mills, nearly a thousand men were jammed aboard.

Disembarking at Kellogg, many men sought "liquid courage" while others piled the dynamite into a five-foot pyramid in the street. Shortly thereafter, a group turned toward the Bunker Hill concentrator—one of the world's largest—which had cost the company some $250,000.

About a half-mile from the concentrator, this forward party halted. Riflemen fired toward the concentrator, and a 28-year-old union man was killed by his own colleagues. A non-union worker was shot in the hip and died a few days later. Another prisoner, a Bunker Hill company stenographer, was slightly wounded.

Sixty boxes of dynamite were placed at three locations beneath the concentrator. At 2:35, the union men lit the fuses. In a few seconds three consecutive blasts reduced the concentrator to splintered wood and billows of dust. The Bunker Hill office, and all its records, were also destroyed.

In bed with a severe case of the grippe at Boise's St. Alphonsus Hospital, Frank Steunenberg was unable to attend to state business. But against his doctors' advice, he hurried to his office, and met with his war cabinet. With all 500 members of the Idaho National Guard currently on duty in the Philippines, Steunenberg had no troops. He wired President McKinley, asking him to call in U.S. military forces.

The president had, by the evening of the 29th, delegated the matter to the War Department, where Assistant Secretary George D. Meiklejohn was temporarily in charge. McKinley, relentlessly political, avoided situations that might damage his reputation. The president, wrote William Allen White, "walked among men a bronze statue, for thirty years determinedly looking for his pedestal."

Adjutant General Henry C. Corbin chose the operation's commander, Brigadier General Henry Clay Merriam. Hastily assembling his field kit, Merriam and a young aide-de-camp set out for Boise on May 2.

In the general's mind his dismounted cavalry of 65 troopers was only a supplement to the force on which he counted to restore order: the Twenty-Fourth Infantry Regiment.

The Twenty-Fourth was widely regarded as one of the best of the 17,000 troops in the continental U.S. But it was also one of the army's four regiments of "colored" troops led by white officers. Merriam may have summoned these troops to ensure that his men wouldn't bond with the white rioters.

Reaching the Kellogg depot at noon on May 4, Merriam was delighted to find a contingent of the Twenty-Fourth. Also on the platform was Steunenberg's newly appointed personal representative in the Coeur d'Alenes, Bartlett Sinclair, the state auditor. He had been given authority to use all means necessary to suppress rioting and punish the guilty. On May 1, Sinclair had gone to Wardner to supervise the first round of arrests by state deputies.

On May 4, Sinclair organized a more ambitious venture into the Burke mining camp, where the Dynamite Express had been hijacked.

To Sinclair it was clear that the entire community of Burke "had been engaged in the crime" of April 29, so "the entire community, or the male portion of it, ought to be arrested."

Conner Malott of the Spokane Spokesman-Review, who witnessed the events, wrote, "It was one of the most remarkable arrests ever made in any country.

The captors recognized neither class nor occupation." They searched every house, and if nobody answered their thumps, they broke down the door. As Sinclair had ordered, they arrested every male: miners, bartenders, a doctor, a preacher, even the postmaster and school superintendent.

After a transfer by train to Wardner, about 10 P.M., the 243 men were herded into an old barn, 120 feet long by 40 feet wide, where prisoners from Kellogg and Wardner were already detained. The frame structure came to be known as the old bull pen. Sinclair later conceded that the men held there, most of whom had been snatched from their homes and workplaces without so much as a blanket, suffered from the cold.

Ultimately, the prisoners' ranks would swell to 1,000, the number aboard the Dynamite Express. On May 9, carpenters and reluctant prisoners set to work with raw pine boards on a new bull pen, which, for extra security, was surrounded by a six-foot barbed-wire fence patrolled by Winchestertoting soldiers. Conditions were primitive. Three inmates died. Accused of aiding and abetting the miners, the county's Populist commissioners were confined for days in the tiny guardhouse with only a scattering of hay on which to sleep.

Sinclair installed county coroner Hugh France, a pugnacious hard-liner, as the new sheriff. France summed up his duties tersely: "The disease," he noted, "needs radical treatment."

The day he had arrived in Wardner, Merriam telegraphed Washington: "Indications are most leaders of mob have escaped," he reported, "going east or west into Montana and Washington; others hidden in the mountains."

With Sinclair and Steunenberg pressing for vigorous efforts to capture these men, Merriam authorized a bold strike into Montana and chose as its leader Captain Henry G. Lyon, a seasoned veteran of riot duty.

His 65 black soldiers entrained for Missoula, where they arrested a reported ringleader named Eric Anderson, and later captured another suspect. At Thompson Falls, they made three more arrests.

But Montana officials wouldn't cooperate and attempted to free Lyon's prisoners through a writ of habeas corpus. Finally, on May 10—after intercession from Idaho, Lyon received a telegram from Governor Robert B. Smith, saying Montana "would not interpose any objection to removing prisoners to Idaho without requisition papers." Lyon turned 10 prisoners over at Wardner. One was a Montana resident with no connection to the Wardner events.

The legal deficiencies of the Montana raid were deep: a deputy of one state had no power to arrest citizens in another without authorization from that state. Moreover, it was by no means clear that Governor Smith was actually legally empowered to waive formal extradition proceedings. Altogether, Lyon's raid seemed "a gross violation of the law," as later charged by congressional Democrats.

The slightly recovered Steunenberg met in Spokane on May 12 with 11 of the district's leading mineowners. For four nights he was a guest of Charles Sweeny, an owner of the Empire State Mine. To a Statesman reporter, Steunenberg claimed he was determined to "totally eradicate from this community a class of criminals who have for years been committing murders and other crimes in open violation of the law." He claimed that "the Coeur d'Alene labor organizations have been, and are now, controlled by desperate men" who'd imposed a "reign of terror."

As descriptions of the bull pen and its deprivations filtered out, unions and other labor sympathizers raised hell. On May 14, New York's Central Federation Labor Union protested General Merriam's "unwarranted use of military power to browbeat the striking miners." Its statement was followed by a similar resolution from the Western Labor Union, charging that miners "have been thrown into a corral like so many cattle for the slaughter and have been denied the right of counsel and the actual necessaries of life."

Public charges of such an incendiary nature prompted second thoughts by the bronze statue in the Oval office. Returning to Denver, Merriam found a telegram from the secretary of war ordering him to tell his successor at Wardner "that he is to use the United States troops to aid the state authorities simply to suppress rioting and to maintain peace and order." Alger emphasized that these had been Merriam's original instructions.

With pressure building, the bull pen's inmates were being released in large numbers. Ultimately, only 13 men were tried in federal district court on a minor charge—interfering with the United States mails—based on evidence that the mail carried by the hijacked train had been delayed for 24 hours. Ten defendants were convicted and sentenced to 20 to 22 months in San Quentin.

These convictions scarcely satisfied Steunenberg, who still insisted that murder charges should be brought against some of the April "rioters." By midsummer, a state grand jury had indicted nine men for murder, arson, conspiracy, or some combination of the three. Most were ordinary unionists. James Hawley, one of the prosecutors, said later that the state wanted to try someone of high standing to demonstrate that "the law could reach anyone."

Ultimately chosen was Paul Corcoran, the 34-year-old financial secretary of the Burke Miners Union. The state had no evidence that he had wielded the rifle that killed the non-union worker, or that he had even been present at the scene of the crime. The state, however, did produce witnesses who had seen him riding atop the Dynamite Express.

In early July 1892, the Gem union discovered that one of its most trusted members was an undercover employee of the Pinkerton Detective Agency.

The father of three and a highly respected member of the Burke community, Corcoran went on trial on July 10. The decisive stroke came when prosecution co-counsel William E. Borah, at risk to life and limb, re-enacted Corcoran's putative ride atop the boxcar, grasping a rifle in one hand as the train raced down the track at 30 miles per hour. On July 27, Corcoran got 17 years of hard labor.

Facing an election in 1900, McKinley grew increasingly sensitive to the Coeur d'Alene furor. The War Department sent out a statement noting that "the presence of troops in Shoshone County, Idaho, is due to the request of the Governor of that State. . . . The constitution and laws of the United States required the President to comply with this requisition."

On September 28, the new secretary of war, Elihu Root, wrote Steunenberg, seeking once more to disassociate McKinley and the army from the troubles in Idaho. The secretary said he was "much disinclined" to have U.S. troops detain citizens "who have remained so long without being tried."

Steunenberg urged the administration to maintain the troops but gave the president the assurance he'd sought: "The State of Idaho is responsible for all that has been done in Shoshone County, relative to [the] call for troops, and the arrest, detention and care of prisoners."

Root declared later that the governor was "one of the strong men of the country." Although this was widely publicized, it did not dilute resentment toward Steunenberg, who was seen as a turncoat, a man who sold out his onetime supporters. Samuel Gompers, president of the American Federation of Labor, noted that Steunenberg had been an honorary member of the Typographical Union, adding that noble causes can engender ignoble acts. "Our revolutionary war . . . had its Benedict Arnold," he said. That organized labor should have a Steunenberg "may be cause for chagrin but not for dismay."

With the 1900 presidential race heating up, the furor became politicized. In December 1899, Congressman John Lentz, a partisan Ohio Democrat, demanded an investigation of charges that Merriam had imprisoned hundreds of United States citizens "under the most brutal and tyrannical conditions" and had otherwise violated the rights of Idahoans. The Committee on Military Affairs convened in Washington early in the New Year to hear testimony from the miners and many others.

Merriam spent four days at the witness table, but the governor got an antagonistic eight-day grilling. Representative Lentz vented his fury. "You do go breaking into the houses of innocent men and women, through soldiers, do you not?" he asked.

"I refuse to reply to such a question as that," said Steunenberg. ''It's an insult."

But he never dodged blame.

"I assume responsibility," he said, ''for every arrest made in Shoshone County. ... I acted according to my . . . conscience and desire to bring order out of chaos."

In mid-March 1900,

Steunenberg encountered F. B. Schermerhorn, a friend from the Iowa Agricultural College. Remarking, in melancholy tones, that this might be their last meeting, he produced a well-thumbed stack of letters threatening his life. "He knew that he was a marked man," Schermerhorn recalled, "and that it was only a question of time as to when the Federation would get him."

III

"When a detective dies, he goes so low that he has to climb a ladder to get into Hell. . . When his Satanic Majesty sees

him coming, he says to his imps, "Let him start a Hell of his own. We don't want him in here, starting trouble. "

—"Big Bill" Haywood

After the inconclusive questioning of several suspects, the attention of those investigating the murder of Frank Steunenberg was drawn to a man who had been in Caldwell on and off since September. On December 13 he'd signed the register at the Saratoga as "Thomas Hogan" of Denver. Dressed in a dark three-piece suit and a bowler hat, evidently "well supplied with money," he claimed to be an itinerant sheep dealer. Or a gambler. Other times he seemed interested in real estate. He was known to sleep late in the forenoon—a mark against him in Caldwell.

Most of the time he lounged around the hotel bar, playing cards. Cy Decker, the bellboy, thought he was "a nice little man" with hands "as soft and white as a woman's." Clinton Wood, the desk clerk, had noticed that Hogan seemed nervous during Christmas week. In a talk with Wood about Steunenberg after the explosion, Hogan said that when the governor left office he'd got a "big wad" from nor them -Idaho mineowners.

Before the murder, Hogan had been in the Saratoga's cardroom kibitzing a game of solo whist. He left briefly, but returned three minutes after the murder. (A detective later found that it took two minutes and 56 seconds to go from Steunenberg's gate to the Saratoga.) Half an hour after the explosion, Hogan was in the hotel dining room, but the waitress noticed that he ate very little.

On Sunday morning, George Froman, Caldwell's ex-marshal, passed the Saratoga with his friend Peter Steunenberg. Froman had been one of the first people whom Hogan had approached. A real-estate agent now, Froman had assumed the newcomer was "on the square" when he said he was looking for sheep and grazing land. When Hogan told Froman he was a Mason, the agent invited him to the annual installation banquet at Caldwell's Mount Moriah Lodge No. 39. But the traveling man revealed himself as ignorant of Masonic matters, and Froman grew suspicious.

Froman said, "He has plenty of money, but he doesn't have any business here. And a coupla times he asked about Frank."

Pete passed this on to Joe Hutchinson, the aggrieved former lieutenant governor. Meanwhile, a Sheriff Brown, who was visiting from Baker County, Oregon, thought he recognized Hogan as a miner he'd known in the Cracker Creek section of eastern Oregon. Hogan stoutly denied ever being there.

On the morning after the explosion, Hutchinson talked with several of the Saratoga's employees, who provided new information.

A Japanese chamber man known as Charlie Jap looked after Hogan's room at the hotel, and told Hutchinson, through an interpreter, that he'd worked on the railroad and was familiar with explosives. One day, in front of Hogan's bed, he'd noticed a "white substance" similar to guncotton used for blasting on the railroad.

Lizzie Vorberg, a waitress in the Saratoga's dining room, found Hogan a "perfect gentleman." He had a rifle and, on occasion, would invite Vorberg to go target shooting. A few days before the assassination he had grown "gloomy and morose" and told her, "You think me a good fellow, but I am not. Some time you may learn what a villain and scoundrel I really am and despise me for all time."

When Hogan entered the dining room after the explosion, Vorberg recalled, his face was white and his hands trembled. He didn't look up or smile, and kept his eyes on the tablecloth. Suddenly, with an "icy chill" in her heart, she realized that he was the assassin, and she should run to denounce him. But somehow she couldn't.

The next day, Vorberg got Hutchinson the key to Hogan's room, No. 19, on the second floor. It afforded a good view across Seventh Avenue into the governor's office at the bank. While Vorberg's sister stood guard, Hutchinson, George Froman, and Jasper P. "Jap" Nichols, the Canyon County sheriff, keyed in. They found that towels had been draped over the inside doorknobs so as to block the keyholes. In the chamber pot they found traces of plaster of Paris, which investigators believed had been used to hold elements of the bomb together. On the carpet they found traces of the powder Charlie Jap had described.

At the Canyon County Probate Court, the first business of 1906 was a complaint charging Hogan with murder in the first degree.

Soon after the jailhouse door slammed on the accused, a husky man with a walrus mustache stepped off the four P.M. train from Spokane. Captain Wilson S. Swain was northwestern manager of the Thiel Detective Service, headquartered in Chicago. The ever confident Swain arrived in Caldwell with a reputation for aggressive law enforcement and a spastic trigger finger which had been proven lethal.

After six years with Thiel's Spokane branch, Swain enjoyed close relations with the Idaho mineowners. He had supervised the agency's undercover infiltrations of union operatives into the mines and smelters to report on the union.

The moment Swain heard of Frank Steunenberg's assassination he calculated its connection to northern Idaho's persistent mining unrest. He wired Governor Gooding to say that he and several Thiel "operatives" were on their way.

The day after the murder of Steunenberg, Charles O. Stockslager had placed a call to the Pinkerton National Detective Agency in Denver, asking to speak with James McParland, the manager of Pinkerton operations west of the Mississippi.

Stockslager, Democratic chief justice of the Idaho Supreme Court, hoped to unseat Governor Gooding in the gubernatorial race. He saw the murder of Steunenberg as a political wild card which he hoped to play to his advantage. He and McParland had known each other for two decades. With a friend serving as chief investigator, Stockslager knew he might influence, if not actually control, the course of the inquiry.

Stockslager had asked the famously eccentric detective to catch the first train north. McParland demurred; Pinkerton protocol required that such requests go to the general superintendent in charge of the appropriate division within the region—in this case, James Nevins in Portland.

The next afternoon—New Year's Day— Stockslager drafted a telegram to Nevins. Governor Gooding had initially gone along with the McParland idea, and Stockslager wired his friend to prepare for departure.

But before Gooding could send his wire to Nevins, Swain had wired with the news that he and his operatives were on their way. Swain's association with the Coeur d'Alene mineowners put the governor in a bind; the mineowners were a powerful constituency he could ill afford to offend.

Undeterred, Stockslager continued to press for the Pinkertons, if only as partners with Thiel. The competitive Swain couldn't have welcomed this notion, but eventually acquiesced. The Pinkertons were then officially invited to join Thiel in the case.

The turn of the century was a boom time for the Pinkertons. In 1899 alone the agency had hired 58 new detectives, the next year another 65.

James McParland was the possible model for a celebrated Dashiell Hammett gumshoe who "could spit icicles in July."

Between 1895 and 1907 it opened 12 new offices, bringing its national network to 20.

The agency had become well known during the lawless period following the Civil War. A host of new banditti—the Youngers, the Daltons, the Renos, the James boys—had brought bloody terror to the plains, robbing trains and banks. "It must be war to the knife and knife to the hilt," Allan Pinkerton declared. Sometimes the agency's methods, which included kidnapping, seemed worse than those of the criminals. The men certainly believed in settling scores. When Pinkerton lost three agents in his pursuit of Frank and Jesse James and their allies, the Youngers, he vowed revenge. Hearing that the James boys were visiting their mother at her farmhouse in Clay County, Missouri, the Pinkertons threw an explosive into a window; it tore an arm off the Jameses' mother and killed an eight-year-old brother. But the James boys themselves weren't there.

Labor's Samuel Gompers noted somewhat later that "never has the private detective been used to such an extent, or with such unscrupulousness," as during the first decade of the 20th century.

Before leaving for Boise, McParland wrote superintendent Nevins in Portland, suggesting that the Steunenberg case could have important consequences for the agency—by weaning the mineowners away from Thiel. "This is one of the most important operations ever undertaken in the Portland District," he wrote, "and if through our offices we are successful, it will mean a great deal so far as the mine operators are concerned."

Shortly after Hogan had a hearing, Swain and Sheriff Nichols searched the prisoner thoroughly for the first time and found, secreted in his shoes, keys to his trunk, a suitcase, and a valise. The trunk contained clothing (a blue Cheviot coat, a Panama hat, two striped flannel nightshirts, a pair of balbriggan drawers); two pairs of rubbersoled shoes, one pair still wet and muddy; a stack of calling cards for "Thomas Hogan, Silverton, Colorado, Agent Mutual Life Insurance Company"; a fishing rod with tackle; a Winchester shotgun, sawed off so it could be hung around the neck and concealed under a coat; and a cloth mask.

In the valise they found a fishing reel with the line missing; a pair of field glasses; an electric flashlight; a set of brass knuckles; a loaded Colt automatic with a shoulder holster; 21 shells; a fuse; a pair of wire nippers of the kind miners used to set caps in gunpowder; a sack of plaster of Paris; four packages of chemicals, several of which were found to contain explosives; and a leather postcard with New Year's greetings addressed to Charles Moyer, president of the Western Federation of Miners, the Denver-based organization that represented all gold, silver, lead, and copper miners west of the Mississippi.

After completing this inventory, the investigators went to the Steunenberg house, where they picked up a few good tracks in the snow. When the wet shoes found in Hogan's trunk were fitted to these tracks, they—and particularly a set of nails in the soles— matched perfectly.

While examining hotel registers in Caldwell and Nampa, two of Swain's operatives discovered that Hogan had checked into hotels in both towns during the preceding months with a man named J. Simmons. From his description, the detectives suspected that Simmons was actually L. J. "Jack" Simpkins, a former organizer for the Western Federation of Miners in northern Idaho and, since 1902, a member of its executive board. When agents produced a photograph of Simpkins, several hotel employees said that he was indeed the man they'd seen.

Meanwhile, Sheriff Edward Bell of Teller County, Colorado—who had sped to Caldwell with an attorney of the Colorado Mine Owners Association—took one look and identified Hogan as Harry Orchard, a miner who had worked in the Cripple Creek-Altman region. This identification was confirmed by Sheriff Brown of Baker County, Oregon, who had thought Hogan reminded him of Orchard.

Another piece of the puzzle fell into place the same day with the arrival of a telegram from Spokane, paid for by the law firm of Robertson, Miller and Rosenhaupt. The message said simply: "To T. Hogan, care sheriff, Caldwell, Idaho: Attorney Fred Miller will start for Caldwell in the morning, [signed] M." Since Hogan had sent no messages since his arrest, Fred Miller must have been acting on his own initiative or in response to some client's wishes. The firm had close ties to the mining unions and had represented Idaho miners charged with serious crimes in 1899.

At seven the following Wednesday evening, as arranged, McParland met Stockslager and Gooding at Boise's best hotel, the Idanha. The governor told McParland that he hoped the Pinkertons would work "in conjunction" with Thiel. McParland flatly refused.

According to McParland's report, the governor, "a strong willed man," pondered the matter, then told the detective: "I accept your proposition."

Dashiell Hammett is said to have pat-

terned the Old Man in his Continental Op series after James McParland. No one can say for certain. But Hammett seems to have him right in Red Harvest: "The Old Man . . . was a gentle, polite, elderly person with no more warmth in him than a hangman's rope. The Agency wits said he could spit icicles in July."

McParland had begun on the Pinkerton agency's lowest rung, as a spotter on the city's trolleys, watching conductors suspected of pocketing fares. But he caught the attention of Allan Pinkerton, and was handed one of the most dangerous—and rewarding—jobs in the agency's history: infiltrating the Molly Maguires, a secret society in Philadelphia inspired by a group that had operated in north-central Ireland, which had threatened, beaten, and sometimes killed English landlords.

Infiltration had long been one of Allan Pinkerton's crime-fighting techniques, but this assignment required a special breed of operative. Since the Mollies were believed to be Irish Catholics, the agent must be one himself. Since they worked in mines, he must be strong enough to bear heavy manual labor. He should be a gregarious sort, who could drink and roughhouse. And since the Mollies were regarded as ruthless killers, he should be unmarried, so if it came to that, he wouldn't leave behind a widow and a brood of helpless babes.

If the Mollies had discovered McPar-

land's treachery, his penalty would almost certainly have been death. Twelve dollars a week was modest pay for such a risk. Pinkerton wrote that McParland would have to "degrade [himself] that others might be saved." The "savage" nature of the Mollies, on the other hand, allowed McParland to go beyond civilized techniques—to treachery and perhaps provocation of violence—in extirpating them.

Ultimately, 20 Mollies were convicted and sentenced to death. On June 21, 1877—Black Thursday in IrishAmerican circles—10 men were hung in the yard of the red-brick Schuylkill County jail in Pottsville, 4 others died in Mauch Chunk, 40 miles to the east. Over the next two years, 10 more Mollies went to the gallows.

Of the 20 deaths, McParland could be directly credited with 9, including a broad swath of the society's leadership. Indirectly, McParland's testimony paved the way for executing the other 11 men and sentencing another 26 to terms in county jails, as well as putting a price on the heads of 9 or 10 fugitives.

It was the 20 executions, the affecting stories of Molly after Molly walking to the gallows in the pale light of dawn, often holding a single rose sent by a wife or girlfriend, that stirred people's morbid curiosity. Some wondered how such men's deaths affected the detective who sent them there. After all, these were men with whom McParland had lived for two and a half years, working in the mines, singing ballads, swapping yarns, and getting drunk. Did he feel even the slightest pang of regret?

CONTINUED ON PAGE 291

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 286

Apparently McParland was able to move beyond whatever reservations he might have felt. For years he basked in the admiration of politicians, the press, and the public.

At 2:15 P.M. on Monday, January 22, McParland, whose heel had been amputated after a case of frostbite and who got around with the help of a gold-headed cane, boarded the streetcar outside the Idanha Hotel. He rode to the end of the line, at the eastern edge of town. There he was met by Warden Eugene L. Whitney, attended by two trusties, who drove him in a rig to the Boise penitentiary. Whitney escorted McParland to his office, introduced him to Harry Orchard, then left the two men alone.

Taking their seats on hard wooden chairs, the detective and the prisoner studied each other. Orchard saw a corpulent man of 62 with a broadbrim hat pulled well down over his forehead, covering all but a few thin strands of silver hair; a silk cravat fixed with a jeweled stickpin; and, behind gold-rimmed spectacles, a pair of shrewd blue-gray eyes, sizing him up.

What McParland saw was a stocky (five-foot-eight, 180-pound) man half his own age, whose face struck the detective as "about as determined a countenance as I have ever seen on a human being, with the most cold, cruel eyes I remember having seen."

McParland led off with a carefully prepared statement of some 25 minutes, in which he argued the case for cooperation with the prosecutors. If Orchard admitted his role, and gave evidence about his co-conspirators, he might reasonably expect a certain leniency in his sentence.

McParland asked if Orchard knew of the prosecutions of the Molly Maguires in the Pennsylvania coalfields some 30 years before, in which several important Mollies who became state witnesses were spared the death sentences imposed on the others?

Oh yes, Orchard knew about the Molly Maguires.

Had he ever seen a photograph of James McParland, the Pinkerton detective who assembled the most damaging evidence against them?

No, Orchard said, he hadn't.

Well, the detective said with calculated flourish, I am that McParland.

Once Harry Orchard realized just who his visitor was, he sat a little straighter in his chair. Quick to exploit the opening, McParland returned to his lesson: the happy fate of the Mollies who had turned state's evidence, notably one Daniel Kelly, alias Manus Cull, alias Kelly the Bum.

Orchard paid close attention to McParland, but offered nothing. Eventually, he began to complain that it wasn't right to put him on murderer's row before he was even tried. His cell was cramped, he said, and he needed exercise.

McParland explained that Orchard was in the pen to "protect him from his friends, as he was a menace to those whose orders he had obeyed, until such time that they killed him or that the state convicted and hanged him."

Harry Orchard struck McParland as haviig "about as determined a countenance as I have ever seen, with the most cold, cruel eyes I remember."

At 5:30 P.M., after three hours of conversation, McParland left the penitentiary, and that evening he gave the governor such a detailed briefing on his meeting with Orchard that the pair didn't adjourn until a half-hour past midnight.

The second meeting between the detective and the accused assassin lasted some three and a half hours. According to his reports, McParland began by asking whether Orchard had thought about their conversation, particularly about the treatment of state witnesses. Orchard said he didn't quite understand why the detective seemed to have such an interest in him.

Oh, McParland said, in one respect he had no interest in him whatsoever, no more than he would have in any other "wilful murderer." On the other hand, as an advocate of law and order, he had an interest in the welfare of not only Idaho but every state that was affected by the blight of the Western Federation of Miners. And knowing full well that Orchard was simply the tool of the federation's inner circle—something Orchard himself surely knew—he couldn't help having a certain sympathy. Clearly, McParland said, Orchard was a man of intelligence and reasoning. This was indicated by the shape of his forehead.

When Orchard asked if they were speaking confidentially, McParland assured him that they were. "That being the case," said the prisoner, "let us suppose a case for the sake of argument. I will now say to you I am guilty of the crime as charged. I have committed the crime." He paused.

"Now you understand this is not a confession," Orchard put in, "but for the purpose of getting information that I want, or rather for argument's sake." McParland readily assented.

"Now, you are the detective; you have already stated to me that you have absolute proof of my guilt. Such being the case, why do you come to me and talk to me as you have done?"

McParland reminded the prisoner that, on the first day they'd spoken, he hadn't asked whether Orchard set the bomb that killed the governor. The state had "proof positive" of that. But since Orchard was the tool of the W.F.M. inner circle, hanging him would give the state little satisfaction. If he'd confess, the state would "no doubt take care of him." But if he confessed, he must not cover up for anyone.

Orchard paused, fixing the detective with a hard look. "Suppose," he asked, "several parties had guilty knowledge of a murder that was committed and were not present at the murder, what good would it be for the murderer to make a confession?"

Absent other evidence, McParland went on, the state would simply try you, "convict you and hang you, but if you confessed, it would be quite different as your testimony would reach the very foundation and the head of these cut-throats known as the Inner Circle of the Western Federation of Miners. This being the case, the State would gladly accept your assistance as a State witness and see that you are properly taken care of afterwards." (In his report, McParland hastened to add that he hadn't promised Orchard immunity from prosecution, or even from the death penalty, though surely he came very close.)

According to McParland, Orchard exclaimed, "My God, if I could only place confidence in you. I want to talk. I ought to place confidence in you. . . . You certainly have not got to build a reputation as a detective, and I am satisfied that all you have said is for my good.

"I don't now look upon you as a snide detective, the same as the damned sons-ofbitches that they threw into the cell with me at Caldwell," he continued, according to McParland's report. "If it were not that their actions were so contemptible I would have pitied them. They are the kind of men that swear men's lives away. I know that you would not take the witness stand and testify as to one word that has passed between you and I here, nor would you add a word to what I have said. I have that much confidence in you."

Orchard may indeed have made the statements as reported, but they seem a trifle too convenient. The detectives placed in Orchard's cell at Caldwell were Thiel men, operatives of McParland's bitter competitor. It suited McParland's purpose to have Orchard disparage his rivals. Moreover, the encomium to McParland placed in Orchard's mouth fit perfectly with the way the legendary detective wished to be perceived—as the senior statesman nonpareil of his profession.

McParland returned to Orchard's cell day after day accompanied by his personal stenographer, Wellington B. Hopkins. Hour after hour, Hopkins took the confession in shorthand. By Thursday, February 1, the Great Detective held in his hands 64 pages of foolscap, the most extraordinary confession in the history of American criminal justice. Not only did Harry Orchard confess to setting the bomb that killed Frank Steunenberg, he accepted responsibility for killing 17 other men—two supervisors in a mine explosion, 13 men in the bombing of a railroad depot, a detective gunned down on a Denver street, and an innocent passerby who picked up a booby-trapped purse intended for somebody else. He also acknowledged attempting to assassinate the governor of Colorado, two Colorado Supreme Court justices, an adjutant general of Colorado, and several corporate officials, all on behalf of the inner circle of the Western Federation of Miners, particularly Charles H. Moyer, the federation's president; William D. "Big Bill" Haywood, its secretarytreasurer; and George A. Pettibone, the former Coeur d'Alene miner who had been imprisoned for a time after the hostilities of 1892 but was now an honorary member of the organization and a close adviser. Finally, Orchard identified other men, including Jack Simpkins, who had been accomplices.

Orchard's confession was so damning that McParland had to ask him whether he thought McParland himself or anyone else had used force or coercion to obtain the statement or had made any promises of immunity. To both questions, Orchard answered no.

Then why, McParland asked, would anyone incriminate himself and his confederates in this fashion?

"I awoke," said the accused man, "as it were, from a dream, and realized that I'd been made a tool of, aided and assisted by members of the Executive Board of the Western Federation of Miners, and once they had led me to commit the first crime I had to continue to do their bidding or otherwise be assassinated myself, and therefore, not caring what would become of me, knowing that I did not deserve any consideration ... I resolved, as far as in my power, to break up this murderous organization and to protect the community from further assassinations and outrages from this gang. That is all I have got to say on this matter." At the bottom of the last page, James McParland added the following note, an appendation offered in a spirit similar to his other "observations": "Orchard broke down and cried several times while making the above statements, but seemed very much relieved after he got through."

IV

"The jury are the most wonderful-looking men I've ever seen. They were all ranchers with the bluest eyes, like sailors' eyes, used to looking at great distances. They made me think of Uncle Sam ... without the goatee.

They were magnificent. "

—Ethel Barrymore

The most celebrated book of 1907 was The American Scene, the fruit of Henry James's year-long sojourn in his native land after an absence of 22 years. Twined in a dense thicket of Jamesian prose was a cranky, if original, view of America at the century's turn. Mildly apprehensive as he toured the Hudson River Valley in Edith Wharton's new motorcar, the expatriate had come in search of the "spirit" of the crude, pushy land he had once called his own.

What James discerned in Americans was a new kind of willingness, even eagerness, to live their lives in public. Some dated the change that James perceived to an evening in the 1890s when a former champagne agent named Henry Lehr induced Mrs. William Astor, the diamond-tiara'd queen of New York's aristocracy, to attend a dinner at Sherry's restaurant. The next morning, a society reporter exclaimed, "I never dreamt it would be given me to gaze on the face of an Astor in a public dining room." Henceforth, it was permissible for even the most exquisite members of the Four Hundred to venture into the public realm, where the eyes of the nation were increasingly focused.

The attention drawn by the trial of "Big Bill" Haywood and his fellow accused was further evidence of the new importance of things public. It was one of the first national events that would draw the collective attention of Americans in the decades that followed. Like those dramas—from crimes and assassinations to political scandals—that came later, it revealed not only the voyeurism of America, but also, in microcosm, the currents, conflicts, and values of a specific moment in American life.

The trial followed an almost certainly illegal Pinkerton-style, McParland-concocted extradition, or kidnapping, of the three defendants from Denver to Idaho. It was accomplished, with the help of the Union Pacific Railroad, through the use of a special train, later nicknamed "the Pirate Special" by socialist critics. Tracks, with the help of the railway companies, were cleared for most of the delicately timed, throttle-out mission. The special train consisted of a steam engine and three chair cars. Food ($44.95 worth) for the hungry servants of justice was supplied by Denver's Watrous Cafe, and it was a big spread according to the standards of most Colorado cookhouses or campfires: 20 turkey sandwiches, 20 chicken sandwiches, 20 beef sandwiches, 20 ham sandwiches, six cans of sardines, a quart of dill pickles, five bottles of olives, a bottle of mustard, three jars of raspberry jam, a basket of apples, three dozen hard-boiled eggs, a loaf of rye bread, a loaf of white bread, several pounds of Swiss cheese, a hundred cigars, three dozen quarts of Budweiser beer, and a quart of Old Crow bourbon.

The raid went off smoothly, but even the deputies from Iowa had some surprises. "Big Bill" Haywood, the towering, radical legend who supplied the Western Federation of Miners with both its volcanic anger and its penchant for violence, had told his wife, Nevada Jane Minor, that he would be spending the evening at a Turkish bath. When authorities burst in on him he was stark naked and in the company of his lover, stenographer, and sister-in-law, Winnie Minor. But the extradition was a legal nightmare; the subjects were literally abducted in violation of existing procedural regulations. Socialist leader Eugene V. Debs and other members of the American left would make the unorthodox methods of the reviled Pinkertons and police authorities into a national cause celebre which would remain a crucial issue throughout the legal battle, even after a Supreme Court ruling supporting the State of Idaho.

The prosecution team—given the technicalities of the extradition and the lack of substantial evidence against the indictees—faced a difficult day in court. The chief prosecutors were former U.S. attorney and Boise mayor James Hawley, the very model of a rough-hewn Western attorney, and William Borah, a brilliant courtroom attorney who was also Idaho's most accomplished orator and Boise's most celebrated playboy. (He was dubbed "town bull," and according to legend was a particular favorite at two of the city's most notorious bordellos— Hattie Carlton's and Dora Bowman's. Later, he was rumored to have fathered a child with Alice Roosevelt Longworth, the married daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt). A close friend of Frank Steunenberg's, Borah worked for a quarter of Hawley's fee. The salaries of the prosecutors would become a source of contention and debate when evidence appeared that, despite Governor Gooding's denial, Hawley's fees were partly being paid by the mineowners, who were also underwriting detective work and other state expenses.

The Western Federation of Miners, backed by the International Workers of the World and the rest of organized labor, were determined to give Haywood and company the best defense available. Chosen for the job was famed defender of the dispossessed Clarence Darrow, who during the winter of 1902-03 had played a starring role in another national drama, the bitter strike by Pennsylvania's anthracite miners. Darrow's inspired advocacy had given the union a notable victory, which Samuel Gompers described as "the most important single incident" in American labor history.

Darrow was something of a boulevardier, with literary panache to match his radical glamour. One newspaper remarked upon his "downright ugliness," but the novelist and social reformer Brand Whitlock termed it "a sort of beautiful ugliness," calling Darrow's smile "as winning as a woman's." George Bernard Shaw detected something wild in him. "With that cheekbone," said Shaw, "he wants only a few feathers and a streak of ochre to be a perfect Mohican."

Darrow spent the late spring and summer of 1906 rallying his forces. Knowing that he was confronting a formidable array of detectives under McParland, he put together his own detective force. McParland belived that, in the early summer of 1906, the Thiel agency turned, with its considerable information, to the aid of the defense.

By the first days of May 1907, scores of newcomers to Boise were shouldering their way through the brass doors of the Idanha Hotel and streaming across the gleaming Italian marble floor of the lobby to the reception desk, where the manager, E. W. Shubert, presided in black cravat and gray morning coat. There were defense attorneys (the prosecution team was "home-grown"), detectives from both camps, witnesses, reporters from New York, Chicago, Portland, and Denver, and a motley crew of stenographers, bailiffs, retainers, informants, grifters, courtesans, prostitutes, and all the other riffraff that public entertainments of the era invariably attracted.

Orchard confessed to setting the bomb that killed Steunenberg, and accepted responsibility for 17 other killings, one involving a booby-trapped purse.

For 15 months—since Governor Gooding and his family, in fear of assassination, had fled to a third-floor suite in the care of bodyguards—the hotel had served as prosecution headquarters. Governor Gooding had a close relationship with the place. His inaugural ball had been held there, with 800 of the state's elite waltzing in the glow of Japanese lanterns. One Sunday on the eve of the trial, Mrs. Gooding presided at a luncheon there, as if to demonstrate that she and her husband were unafraid of assassins.