Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

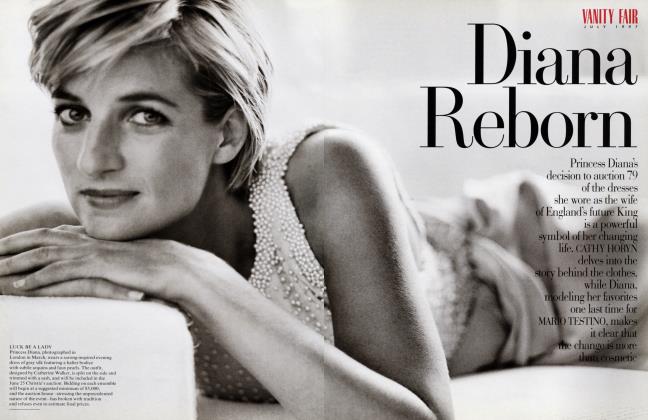

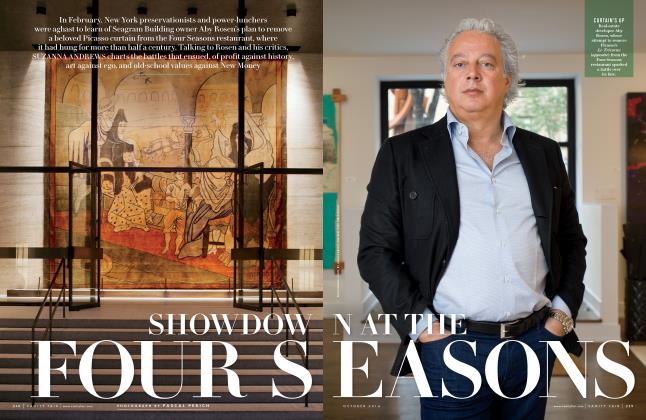

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Last Explorer

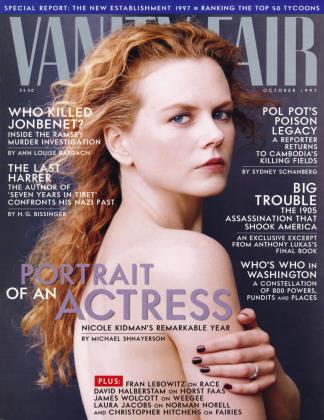

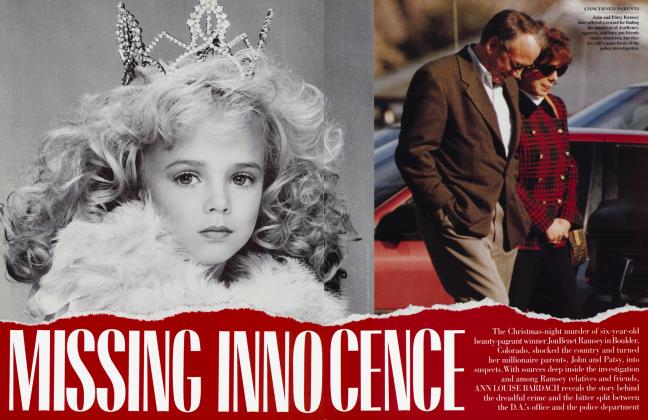

One of the century's greatest explorers, Heinrich Harrer scaled the "Murder Wall" of the Alps, ventured deep into the Congo and the Amazon, and, after one of the most astonishing escapes of World War II, became the Western guru of Tibet's young 14th Dalai Lama. But even as Brad Pitt stars in a movie based on Harrer's 1952 best-seller, Seven Years in Tibet, H. G. BISSINGER recounts, the 85-year-old Austrian national hero has been confronted with a terrible secret from his past: that he was a member of Hitler's SS

H. G. BISSINGER

"I was ambitious," said Harrer. "The purpose of life is to have a plan and stick to it."

In a rare act of Hollywood homage they traveled thousands of miles just to see him, to the treecovered hills of southern Austria. The remarkable caravan— Brad Pitt in goatee, his co-star David Thewlis in a pair of tiny, angular sunglasses, French film director Jean-Jacques Annaud, obsequious studio executives—looked like miniatures in the silent hills. But nothing, it seemed then, could make the man they had come to find look small.

Heinrich Harrer was a legend, the last of the great ones, along with Sir Edmund Hillary and Jacques Cousteau. David Swanson, a past president of the Explorers Club, ranked Harrer among this century's five greatest explorers. Galen Rowell, the superb outdoor photographer, summed him up: "There will never be another person to do this kind of renaissance adventuring."

In .1938, unfazed by the deaths of eight predecessors, Harrer and three others became the first to scale the 5,900-foot "Murder Wall" of the Eiger peak in Switzerland.

He had been a member of the 1936 Austrian Olympic Ski Team and would become a championship golfer. But his greatest moment, his ascension to the Roof of the World, where he climbed the steps up and up to the Dalai Lama's palace of the Potala, was still to come. He would never forget the smell of rancid butter there in the dark and gloomy corridors, just as he would never forget the young boy who, regardless of spiritual divination and title, viewed the world from long distance, through a set of binoculars. A prisoner in a holy cell, the child passed the time by taking apart watches and cameras given to him by presidents and ambassadors.

Until Harrer. The explorer became the gateway to the West for the 14th Dalai Lama, and in 1952 chronicled it all in Seven Years in Tibet, a book which has sold more than four million copies.

By the time Pitt and his retinue called on Harrer in the village of Hiittenberg, the Dalai Lama's former tutor had survived 84 years, but his body remained compact and sinewy, the physique of an exceptional athlete. His hair was as white as the snows of Everest, with tufts rising off the sides like eccentric wings, and he looked a bit like a man who had spent his life concocting potions. But he was anything but mad. His gestures were wildly emphatic yet precise. Everything—the walk, the way he drove, the way he paced— conveyed a heat-seeking drive and sense of purpose.

He wasn't particularly familiar with Brad Pitt, who would be playing him in the $70 million film version of his book. He had seen only one of Pitt's films, Seven, and found its violence ungerly agreed to take the visitors on a tour of the museum named after him with its thousands of artifacts collected from his expeditions to the remote corners of the world: the Congo, New Guinea, the Amazon region of Brazil, Suriname, French Guinea. Later they had gone to Harrer's home, in nearby Knappenberg, and Pitt—swept away by the life that had been spread out before him—had written in the guest book: "It's an honor to sit in your home. It's an honor to share in your life. We will not let you down."

Gracious words. But Harrer nearly always elicited praise. He was an octogenarian with the chromosomes of a teenager. He had given up skiing at 83, but one could still imagine him rushing down the steep slopes, tripping up snowboarders with lightning whacks of his pole, then apologizing as if it were all some accident.

At one point during our four days of interviews, Harrer and his wife drove us across the Alps from Liechtenstein, where they maintain an apartment in Vaduz, to their cabin home in the Austrian hills. Harrer commandeered the driver's seat, impervious to conservative notions of speed. Tour guide and raconteur, he was a showman, enchanted with places that should be routine by now. At other times, he spoke with detachment during the interviews, revealing the cool heart of an explorer who finds near-death and misery just another day at the office. There was the tale of the vicious dog in the Himalayas which he wrestled to the ground and choked until its tongue came out in surrender, not to mention the time in New Guinea when he fell down a waterfall as high as a six-story building and broke 15 bones—including his chin, shoulder, knees, and four ribs along the spine. "When I flew through the air I said, 'Well, this is the end.'"

His tone changed slightly when he turned to the searing reality of being poor and growing up without indoor plumbing. "There is an urge in everybody to excel," he told me. "I was ambitious. Without ambition, you can't succeed." And if there was anything that defined Harrer, it was the desire to succeed, always on his own terms. He married an 18-year-old woman from a prominent family but spent seven years in Tibet instead of coming home after World War II to meet his son.

"The whole purpose of life is to have a plan and stick to it," he said, launching into the story of the time during one of his expeditions when he was reading Michener's Hawaii by night and, in the morning, using the pages he had finished as toilet paper.

His life seemed magical, an unblemished storybook. But Heinrich Harrer had a secret. Amid the glorious tales there was a dark chapter.

It was a small but significant part of his life, something he did not want exposed. Perhaps because he truly thought it was inconsequential. Or maybe because he believed he had somehow lived beyond it, compensated with better deeds, as when, after the Chinese occupation of Tibet, he had spoken out so nobly and forcefully. His bravery had earned the respect of many, including Columbia University religion professor Robert Thurman. "Heinrich clearly spoke with the courage of his convictions," Thurman said.

But the hidden chapter remained, in the form of Harrer's name written in black ink on a file, sitting for years inside the German Federal Archives in Berlin. It was one file among, literally, a million, seemingly lost to the ages.

But it wasn't lost. Because Heinrich Harrer had a nemesis.

And so, nine months after Brad Pitt came to Hiittenberg, there was another meeting. And this time it was not set against the bucolic stillness of the Austrian hills but rather in the "Wegot-a-big-motherfucking-problem-onour-hands" hum of London. The filming of Seven Years in Tibet had been completed. The release had been set. But this was not a meeting of mutual admiration. An executive from Mandalay Entertainment, the company producing the film, was there. And so was Heinrich Harrer's lawyer.

There were no signed guest books, no inscriptions, no museum tours. The mood had changed, and the man from Mandalay was basically suggesting that in October, when the film premiered in the United States, it might be better for everyone if the subject stayed away from the festivities. The contents of that forgotten file showed that in 1938, in his native Austria, the explorer had joined an organization called the Schutzstaffel. But few ever called it that. Instead, it had a simple twoletter designation.

The SS.

In the aftermath of the revelations of his Nazi past, Harrer attempts to be contrite. To a certain degree he expresses remorse, calling it "the worst aberration of my life." But in another breath he seems almost indignant. "I can't go around with a plate on my chest," he says. "Everybody has something they are not proud to show off."

Many have rallied to Harrer's defense, correctly pointing out that he was not a war criminal. He did not commit any atrocities, and the only time he wore an SS uniform was on his wedding day in 1938. In 1939 he left his native Austria to go on an expedition to the Himalayas and did not return to Europe for 13 years. "He is one of the most noble and honorable men that I have ever met," says David Swanson.

But there was still the troubling question of nondisclosure, particularly in a life where so much has been willingly revealed through books and documentary films and the extensive biographical section at the museum. Even a close friend wonders why Harrer did not reveal the secret years ago when his explanation for his activities would have been more plausible.

"Why did Heini not tell people the truth 50 years ago?" asks Trudi Heckmair, whose husband, Anderl, had climbed the Eiger with him. "Every journalist asks this question. He probably thought there was never a proof of it. Now the proof is here and he is a liar 50 years gone. He never did do any harm to anyone. But he always did not tell the truth.

"We always say a lie has short legs," Heckmair continues. "His lie has long legs."

In the afterglow of Brad Pitt's visit, Harrer had been visibly excited.

He had proudly showed off the words that Pitt had written in his guest book and the poster for the movie. There was Brad Pitt in climber's fedora playing him, and there in painstaking replica was the western gate of the forbidden city of Lhasa, just as it looked when Harrer had entered in January of 1946.

"I come back, you see," he said excitedly. "I think this is how life works. It is normal."

He had come full circle, and the movie was the perfect dessert for a rich and full life. Until the revelation.

"The movie is not worth what has happened," he says now, as if longing for those times when he didn't have to worry about spin control or possible absolution but something far simpler:

How to stay alive.

So much of the famous journey to Lhasa in the 1940s seemed surreal, a twisted theme park of horror and wonder.

Harrer and the fellow Austrian he traveled with, Peter Aufschnaiter, came upon valleys of perfect strawberries, only to discover they were infested by leeches that dropped from trees and slithered into openings as small as the eyelet of a shoe. They witnessed burial ceremonies in which bodies—even the bones—were hacked to pieces by professional corpse smashers and carried away by vultures. They heard stories of criminals punished for theft by having their hands cut off. Following the amputations, the offenders were sewn into bodysuits of wet yak skin and thrown off a precipice.

The origins of the trip lay in 1939 when Harrer, then 26 and fresh from his triumph on the Eiger, left Austria to join a German-led reconnaissance expedition to Nanga Parbat in Kashmir. Four previous attempts to conquer the 26,600-foot mountain had failed and the goal was to find a new way up.

But war broke out, and Harrer, Aufschnaiter, and other members of the group were confined in a British prisonerof-war camp near Dehra Dun in India. Harrer and another prisoner escaped for the first time in 1943, but conditions made survival difficult. One night a campsite was transformed into a perfect feast for swarms of giant ants that bit savagely into the skin. Drinking from pools of fetid water resulted in prolonged spells of coughing and vomiting. Harrer dyed his blond hair black in an effort to blend in with the Indian population, but large clumps fell out. Not surprisingly, the prisoners were recaptured.

"It crawled down my spine that I have been standing side by side with the fellow who created such atrocities," says Harrer.

Another try came in 1944 and this one was successful. Five escapees originally set out for Tibet. The goal was to cross the breadth of the country to reach China and, ultimately, seek refuge with Germany's Japanese allies. But realizing the sheer ludi¾ crousness of the trek, three of the escapees went in another direction. Harrer and Aufschnaiter (played in the film by Thewlis) were on their own.

Their drive through the interior of Tibet seemed a brazen act of hubris, but both were skilled mountaineers, two distinct halves blending together in a perfectly complementary way. Harrer was unflinching, sure of himself, opinionated—a risk taker. Aufschnaiter, 13 years older, was self-contained, cautious, rarely swayed by others.

When they had first met at the outset of the Nanga Parbat expedition, Harrer was incredulous that Aufschnaiter, this "old man," as he later called him, would be his guide. But the more he got to know him, the more he liked and admired him, regardless of what he perceived as his limitations. Over the years of their partnership, the importance of conventional strengths paled. Skills that might have seemed a strange measure of a man took on great significance. Harrer later pointed out, of his companion: "After all, he wasn't capable of making a fire with yak dung."

The oil-and-water character of their partnership fostered their survival. "The two made a perfect combination," says Robert Ford, who had been a member of the British Mission in Tibet and went on to work for the Tibetan government in the late 1940s. "When things got tough, Harrer was the one who said, 'Let's push forward.' Aufschnaiter was the one who said, 'Let's hold on. Let's think about it.'"

Traveling southeast, they reached the town of Tradiin after three and a half months, hoping to receive official permission from the Tibetan government to travel deeper into the interior. But permission was denied, and they were told to leave Tibet and head for Nepal. Instead, they continued, finding temporary haven in the mud houses of Dzongka and the 9,000foot altitude of Kyirong. They grew accustomed to the food of the region—a flour made from barley, called tsampa, laced with beer, and horridtasting butter tea. They discovered a monastery's red rooms carved into a rock face 700 feet above the ground.

Reaching the village of Sangsang Gevu, they faced a pivotal decision: whether to make for China—which meant thousands of miles of walking— or, in an attempt to fulfill the dream of every explorer, try for Lhasa. Ostensibly at least, they were only several weeks on foot from the Holy City. But the route they chose to minimize detection, through the northern plains in the dead of winter, seemed insane, a terrain, as Harrer later wrote, "so inhospitable that only lunatics would wish to go there." Supplied with a yak by friendly Sherpas, they set out in December of 1945, heading off into territory as cruel as it was mesmerizing, two lonely pinpoints in the maw of infinity.

On that first night after they made their decision, Harrer had the same feeling in the pit of his stomach that he had experienced scaling the Eiger. Later he acknowledged that he and Aufschnaiter would certainly have turned back had they known what awaited them. The next day, they came to the top of a pass. There, like a vast and merciless ocean, was an unbroken plain of snow and the relentless bite of an ice-cold wind. At the end of several days of trekking, they found sanctuary in a nomad tent, and Harrer spent hours rubbing his toes after discovering signs of frostbite. They argued over turning back, putting an end to an exploration that now seemed like slow suicide. But they forged ahead.

They were forced to camp in the open, and expended so much energy finding the barest staples of survival that they were too tired even to speak to each other. Their hands became stiff with frost; the socks they wore as gloves were of little use. They found some meat to cook and ladled the gravy right out of the saucepan without fear of scalding themselves, because the boiling point was so low. Tormented by the cold, and the lice crawling over their bodies, they were unable to sleep.

At one point they found themselves fleeing from a band of robbers. It was night. The moon was full, and the added sheen of the snow gave them enough light to aim for a mountain pass. But the temperature was somewhere around 40 below. They went on for hour after hour, Harrer's mind seized by hallucinatory visions. At last they stopped, found cover, and tried to eat some tsampa, but the cold was such that the metal spoons stuck to their lips and had to be torn away.

The next day they spied the trickle of a yak caravan being driven by nomads. They marched three hours to join them, and the cruelty of their journey momentarily lifted. On Christmas Eve, a nomad presented each of them with a piece of white bread. "It was stale and hard as stQne," Harrer wrote, "but this little present on Christmas Eve in the wilds of Tibet meant more to us than a well-cooked Christmas dinner."

Using an old travel permit they had received upon their initial entry into Tibet, they successfully deceived local officials into thinking that they had been granted permission to continue their travels into the interior. They pushed toward a chain of mountains called the Nyenchenthangla, with passes as high as 20,000 feet. Making their ascent, the men found the pilgrims' road to Lhasa. They saw prayer flags in vivid colors, and a row of stone tablets with prayers inscribed on them. But the slope of the route was treacherous, a fact confirmed by the skeletons of animals that had slipped and fallen to their deaths.

Harrer suffered a horrible attack of sciatica. He bathed in the warm waters of a natural hot spring to ease the pain, and a crow stole away his last piece of soap. The woolen trousers that he and Aufschnaiter had been wearing were foul and stained. Their shirts were ripped and their shoes were in pieces.

They pushed past the village of Nangtse, and then Tolung, and then into the broad valley of Kyichu. For 21 months they had trekked across the Himalayas. They had gone through more than 62 mountain passes, traveling more than 1,500 miles. Then, after rounding a small hill, they saw something that seemed to have floated down from the heavens:

The golden roofs of the Potala.

The boy had no playmates. He rose at dawn from his bed of hard, woolstuffed cushions, his only concession to luxury a frame that had been painted yellow. He ate his lunch and dinner alone. Virtually all of his regular contact was confined to men two generations older than he was—his two teachers and the three abbots who attended to his food and clothes and

prayers.

In grand public processions, the boy sat in a sedan chair that was carried aloft by 36 attendees. Virtually anything the boy touched, the merest possession, was valued as sacred. He had been given many names: the Holy One, the Mighty of Speech, the Excellent Understanding, the Absolute Wisdom, the Defender of the Faith, the Ocean, the Living Buddha, the God-King.

He had already been designated the 14th Dalai Lama, the spiritual and temporal leader of Tibet. Blit he was still just a boy.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 369

"Heinrich Harrer never did do any harm to anyone. But he always did not tell the truth."

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 338

From his brothers, he heard the stories of this foreign man with yellow hair who taught the monks how to skate. The boy heard about the swimming parties in the Kyichu River. He heard about the makeshift games of volleyball and he could see the picnics. He scanned other streets of Lhasa and other gardens, until there was no more light. At night the doors of the Potala were all locked and bolted. The corridors were empty except for a night watchman.

Years later, after the boy had grown, he told the man what he had felt as he had watched him through the binoculars.

"If I had been free and not the king or not the Dalai Lama, I'm sure I would also have been naughty like you.

"A boy like any other boy."

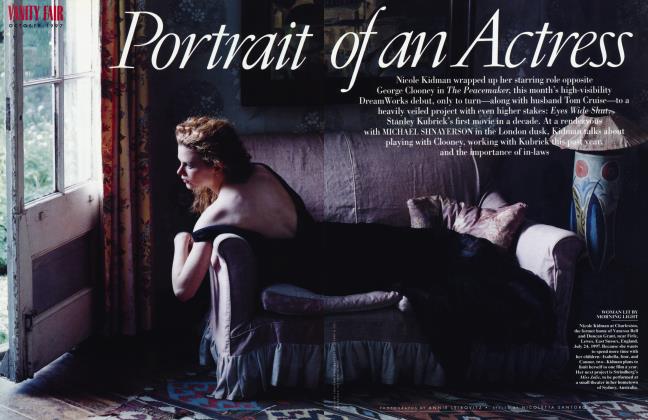

The Dalai Lama's mother saw how isolated her son was, how bereft he was of the joy that her other children experienced. And so Harrer was summoned to the summer palace, the Norbulingka. After the departure of a disapproving regent, the mother thrust the visitor toward the inner garden and a gate guarded by two ferocious mastiffs tethered on ropes. Then the door opened, and there the young boy was. Harrer handed him a white scarf, a token of greeting according to the Tibetan custom. Hie Dalai Lama took it in his left hand, then quickly blessed him with the right.

He was like a genie in a lantern, sealed up tight but now finally unleashed by the Austrian mountain climber. He asked a flurry of questions, so many that Harrer— who had became skilled in the Tibetan language-had difficulty answering them all. The boy wanted to know how a jet airplane flies, how an army tank operates, how Harrer signed his name. He showed Harrer a film projector, which, during his lonely nights inside the Potala, he had completely disassembled and then put back together. The Dalai Lama produced an exercise book in which he had transcribed the capital letters of the Latin alphabet. He insisted that Harrer immediately start teaching him English.

During that summer of 1950, Harrer— with the help of a globe—taught the Dalai Lama about geography and why the time in New York was so many hours behind that in Lhasa. As well as he could, he explained the principles of the atom bomb. Discovering some books that had never been used— The Correct Guide to Letter Writ- ing and English Pronunciation and Spelling— Harrer honored the young ruler's request by beginning their English lessons. Within the little theater that Harrer built inside the summer palace, they watched Henry V.

They made grand plans, dreaming of together leading Tibet out of what Harrer called "the fog of gloomy superstition" without destroying what made it unique. Modem medical care was then nonexistent in this antique land. The Dalai Lama's own brother, having suffered a heart attack, had been revived by a branding iron to his flesh.

The omens were everywhere—freak births, the dripping of water from a gargoyle at the cathedral, the falling of a stone from an obelisk. Then, in August of that year, an earthquake devastated eastern Tibet. Two months later, Communist troops from China crossed the border. "Go now, Henrig," the Dalai Lama told Harrer, fearful of what might befall his friend.

Harrer left Lhasa in November, taking a boat of yak skin down the Kyichu. The Dalai Lama fled temporarily soon afterward. Harrer kept vigil in India, postponing his departure for Europe as long as he could. But someone else was waiting, a boy virtually the same age as the Dalai Lama when he met Harrer. But the relationship was very different. After all, the boy on the pier in Naples wasn't the God-King. Or the Living Buddha He was just Harrer's son.

When Harrer was asked if he felt guilt about not returning home earlier to see the boy, he seemed almost puzzled. "No, why should I?" he inquired.

That very first moment on the pier had been happy and memorable. Peter Harrer, who had turned 12 just 10 days before, ran past the guards and instantly recognized the father he had never met.

Growing up had not been easy for Peter Harrer. His mother had divorced his father and left the boy when he was a year and a half old. Peter was raised by his grandmother, shuttled from place to place.

At the end of the film version of Seven Years in Tibet, Peter Harrer and his father go to the top of a mountain and plant a Tibetan flag together, a symbol of their happy reunion. This never occurred.

Peter Harrer was placed in a series of boarding schools and saw his father only sporadically. "He became a famous person, so he had no time," Peter tells me. "He was away the whole time. We didn't have much of a relationship. I would have liked to have had a family. I never had one."

By the time he was 18, he says, he had gone to almost a dozen different schools.

He returned to live with his father after boarding school, but when Peter was 20, he says, his father, upset with his conduct, threw him out of the house. When the explorer married a second time, his son was not invited. Nor was he asked to attend Harrer's wedding to his current wife, Carina. "That was his personal business" is all Peter will say.

Their relationship improved over time, and father and son now see each other about once a year. Harrer believes that his son retains a residue of anger, but Peter Harrer says he harbors no ill will. His father was an explorer, drawn to experiences that ran counter to family life.

Peter Harrer never tried to follow in his father's footsteps. His life as a technical expert for the Swiss television network in Zurich, with a wife and two daughters, is hardly the stuff of legend. His father was clearly disappointed by the waste of those explorer's genes. But Peter is not sure that Heinrich Harrer could have gracefully handled the competition. "I really do not know whether he would have liked it if I would have been as famous as he is," Peter Harrer says.

"He is the biggest."

The suspicions had lingered for nearly 60 years, ever since the Eiger conquest. Hitler had seized on the mountain's North Face—bending back on itself like a gigantic hangnail—and saw it as the perfect symbol of the Ubermensch. At the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, he offered a gold medal to anyone who successfully climbed it.

Two Germans had tried in 1935 but froze to death. A team of four climbers from Austria and Germany tried a year later. After three of the climbers died, the remaining mountaineer, Toni Kurz, found himself stranded. Attempts were made to rescue him, but one of his arms had completely frozen and eight-inch icicles hung off the crampons of his boots. "I'm finished," he said, another victim of the Murder Wall. Then he hunched forward, the sling he was in swinging as gently as a rocking chair off the face of the mountain, almost to the fingertips of those attempting to rescue him.

In 1938 two Italian climbers perished in the throes of a thunderstorm. Then along came Harrer and three others—Anderl Heckmair, Ludwig Vorg, and Fritz Kasparek. Climbing was different then, equipment and protection more rudimentary. Harrer wore an old hat that he stuffed with an extra set of gloves to soften the blow of falling stones.

The climbers reached the top on July 24, 1938, and were greeted by a swell of hoopla. At a sports celebration in Breslau, Hitler had his picture taken with the four climbers and told a cheering crowd of 30,000, "My, my, you certainly have achieved a lot!"

The picture of Hitler and the four climbers is actually on display at the museum in Htittenberg. When Harrer looked at it last spring, he said of the Ftihrer, "There he is," with a kind of whimsical laugh.

Gerald Lehner had read Seven Years in Tibet as a teenager. The Austrian had been struck by the remarkable saga, but sensed something missing: an absence of a convincing explanation for how Harrer had been able to join the expedition to the Himalayas in 1939. Austria had been under Nazi control in 1939. Every facet of life was in the hands of the Germans, so why would Harrer have been selected for the expedition? Was it just climbing skill? "I always had the feeling that this man had something to hide," said the 33-year-old Lehner, a radio reporter for the Austrian National Broadcasting Corporation.

He looked through old copies of a Nazi-controlled newspaper and discovered that the expedition Harrer had been on had been used for propaganda purposes. He did further research and discovered that an Austrian mountaineer, as early as the 1950s, had written that Harrer had been a member of the SS.

While working in New York, Lehner got a tip that German military records were available at the National Archives in College Park, Maryland. Raising what money he could, he stayed in a youth hostel near the White House. He went to the archives and gave the person who worked there Harrer's name. In five minutes, he had an answer to the question that had nagged at him for 15 years: microfilm records of Harrer's participation in the SS, even a picture. He felt no elation. He spent a couple of days trying to resolve his ambivalence. Then he went to the Holocaust museum, and while he realized that Harrer had never participated in any of the horrors he became convinced of something else: he must confront the hero.

Lehner interviewed Harrer at his home in Knappenberg. According to the journalist, the initial questions centered largely on Tibet and the Dalai Lama, and then Lehner asked about the rumors that Harrer had been a Nazi. At first, says Lehner, Harrer laughed. Lehner then spread out some of the materials he had found; he says that Harrer, when shown documents appearing to be in his own hand, denied that the writing was actually his. Harrer says he was astonished to see the documents, but immediately acknowledged they were his writing. Lehner says Harrer became increasingly indignant and told him he knew some of his chief editors. Lehner adds that Harrer's wife, Carina, remarked at one point, "I was married to a Jew. Why are you asking such questions?" Both men agree that the interview largely disintegrated.

Lehner then teamed up with a writer for Stem magazine, Tilman Muller, who also went to see Harrer, and this time there was no confusion: the explorer verified that the handwriting on the documents was his. Harrer had been a member of the SS since April 1, 1938; his rank, roughly, was sergeant-level. In what amounted to an application to the SS for permission to marry, he and his prospective wife had submitted proof of their ancestry back to 1800. Documents in Harrer's own handwriting further indicated that, in 1934, Harrer had been a member of the SA (storm troopers), another Nazi terrorist group operating illegally in Austria.

In the aftermath of the article in Stern, Harrer said that he had been asked to join the SS in 1938 as a sport and ski instructor and had agreed. He also confirmed that he joined the Nazi Party that same year to qualify as a teacher at the University of Graz. He said he never gave a single lesson as an SS instructor, and that he wore the uniform only once (on his wedding day in December of 1938). He said he had never been part of the SA, but had added that to his application for marriage to speed up the process. In a questionnaire Harrer filled out for the local Nazi Party, he also stated in several answers that he had been a member of the SA since October 1933. But in an interview, he once again said that he had put down such information only to expedite approval of the marriage.

The motivation behind Harrer's recruitment did not appear to be ideological, but rooted in the desire to advance his career. It was a classic case of going along to get ahead.

The three other climbers who scaled the Eiger were never selected for the Nanga Parbat expedition. They were all called into the German military, and one of them, Vorg, died on the Russian front. "The only one who was quite free and independent was Heini Harrer," wrote Anderl Heckmair in his book, My Life as a Mountaineer. While the storm clouds of war moved ever closer, Harrer, in the five-month period between his marriage and the Nanga Parbat journey, contracted to appear in a movie about skiing produced by Leni Riefenstahl.

He said it was only in Lhasa after the war that he saw pictures of the acts committed in the concentration camps. "It. crawled down my spine that I have been standing side by side with the fellow who had created such atrocities," he said, and yet his book never acknowledges what the Nazis did. Hugh Richardson, a member of the British Mission in Tibet during Harrer's stay, said he was not aware of the explorer's Nazi past but knew that he had taken part in "mountaineering activities under Himmler's aegis."

When informed that Harrer had been a member of the Nazi Party and the SS, the unshaken Richardson replied, "Enthusiasm of youth, I suppose."

The movie people did not take the revelations about Heinrich Harrer lightly. The stories started as a trickle, but attracted more attention after Rabbi Abraham Cooper, associate dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center in Los Angeles, announced publicly that he considered Harrer's explanation unacceptable.

The filmmakers tried to act as if nothing had happened. Their approach was novel: in the film, Harrer—until his spiritual redemption at the hands of the Dalai Lama—is portrayed as so arrogant and self-centered that there was no need to directly say that he was a member of the SS.

But behind the scenes they scrambled. "We have to do something," Jean-Jacques Annaud said over the phone to Harrer. Harrer's lawyer, Johannes Burger, made this point: "As much as Mr. Clinton likes to shake the hand of Michael—what's his name, Jordan?—or Michael Tyson before he raped women and bit people's ears off, Hitler liked to surround himself with the athletes of the time."

In London, according to Burger, John Jacobs of Mandalay said that he believed Americans reacted to information in only two ways: very positively or very negatively. There was no such thing as a gray zone, he said, emphasizing his concern that the public would draw negative inferences about Harrer and perhaps distance itself from the movie. The question of Harrer's presence at various activities in conjunction with the opening of the film was raised. Burger said there were only two options: either Harrer would not participate in any of the activities, or he would be a full participant.

"I don't know whether we want that" was Jacobs's apparent reaction to the idea of Harrer's participation. In Burger's mind, this created a bizarre situation: "There it is, his life story; they don't want him to come."

A suggestion was made during the meeting that something needed to be done, and two weeks later, at the end of June, Harrer met with Simon Wiesenthal in Vienna, hoping for some form of dispensation. The meeting was cordial. A picture was taken. Afterward, Harrer was hopeful that Wiesenthal would help moderate Rabbi Cooper's stance. But it didn't work.

Rabbi Cooper said that Harrer had been completely forthcoming with Wiesenthal. He called Harrer "arrogant and gutless," arguing that he had seen Wiesenthal only to stem further damage, not out of any sincere regret.

"Everything is in a total moral myopia," said Cooper. "There are millions of lawyers, doctors, architects, and sports figures who never thought for a second about joining the SS. He never hesitated for a second, never broke a sweat. There has to be some sense of a moral dimension."

The glow and excitement, the infectious enthusiasm Heinrich Harrer had shown when he had displayed the movie poster for Seven Years in Tibet in that pristine cabin in those pristine hills, have dissipated. Slight changes have been made to the film in order to acknowledge his ties to the Nazi Party.

Just months before the revelations, Harrer had expressed the hope that he and his wife would be invited to the U.S. premiere and be a part of all the festivities. Now he muses that it would be better to stay away altogether. "I have the feeling that it is not good to go there," he said, the tone in his voice unfamiliar, marked by doubt and resignation. It was the sound of a man who has finally been conquered—not by the Eiger's Murder Wall, or the leech-infested strawberry fields of Tibet, or bones broken at the bottom of a waterfall in New Guinea. Heinrich Harrer has been changed by something else: the judgment of those who could not effortlessly ignore his secret.

As he had.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now