Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE LADY & THE TITAN

With Standard Oil, John D. Rockefeller built America's first great industrial monopoly, refining and selling nearly 90 percent of all oil produced in the U.S. But by 1902 he faced two threats: a trust-bustin president, Teddy Roosevelt, who would dismember Rockefeller's empire, and a crusading journalist, Ida M. Tarbell, who would destroy his reputation—and unleash his worst nightmare. In an excerpt from a new biography, RON CHERNOW describes how a 45-year-old muckraker hounded the richest man in the world and the most feared mogul of the Gilded Age

By the time that John D. Rockefeller Sr., the co-founder of Standard Oil, retired in the late 1890s, he hadn't yet become history's first billionaire. That came in 1913. But Rockefeller had already created the image of the mythic tycoon. Shrewd and secretive, tightfisted and daring, he plotted his moves in private, universally known but unseen by a public who followed his exploits as wizard of the world oil industry. Aspiring to reclusive glory, he seldom spoke to the press, leaving the curious to ponder his true nature. No other mogul of the Gilded Age was so admired for his financial acumen or so feared for his lethal business tactics.

tusville, Pennsylvania, touching off pandemonium. Eleven years later, Rockefeller and his partners launched Standard Oil in Cleveland with the express purpose of dominating the business. Propelled by ferocious wills, they took an industry disrupted by boom-and-bust cycles and introduced huge economies of scale.

By the 1880s, Standard Oil refined and sold nearly 90 percent of all the oil produced in America, fostering the first great industrial trust. Its kerosene lit America's homes, its lubricants greased the nation's machinery, its fuel fired the boilers of offices and factories. Everything about it seemed colossal, unprecedented, and— to a society schooled in the pieties of individual enterprise—quite terrifying.

Rockefeller's career mirrored the rise of the global oil market. In 1859, Colonel Edwin Drake had struck oil in Ti-

Excerpted from Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., by Ron Chernow, to be published in May by Random House; © 1998 by the author.

The trust's dimensions were vast: Twenty thousand wells poured their output into Standard Oil's 4,000 miles of pipeline and its 5,000 tank cars. Three thousand Standard Oil horse-drawn tank wagons marketed oil in 37,000 towns and cities across America. As the biggest business on earth, with more than 100,000 employees, the combine's power extended across the globe. Sampans laden with Standard's products floated down rivers deep in China's interior, while its kerosene kept lamps flickering in the ancient bazaars of Babylon and Nineveh.

The trust was so huge that, despite the fact that it was dismantled by the federal government in 1911, its offspring-including today's Exxon, Mobil, Chevron, Amoco, Conoco, Arco, and BP America—still largely rule world oil. With a few notable exceptions, such as Gulf, Sun, and Texaco, the major American oil companies of the 20th century are lineal descendants of Rockefeller's creation.

The titan of Standard Oil constructed a self-contained industrial universe, overseeing plants that made acid, chemicals, staves, barrels, wicks, pumps, even tank cars. Though Standard Oil never owned more than a third of the nation's oil wells, that fraction encompassed hundreds of thousands of acres in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio. Rockefeller mostly left the uncertain task of drilling to thousands of independent producers, who then competed furiously to sell him crude oil at the cheapest possible price. As a result, he was loathed by the drillers, who saw him as an omnipotent deity shadowing their lives.

Rockefeller was such a bogeyman in western Pennsylvania that local mothers scolded their wayward children by saying, "Run, children, or Rockefeller'll get you!" His legend grew larger, but he became an even more enigmatic figure. He shied away from being photographed in an oil field or refinery or in his secluded lower-Manhattan office at 26 Broadway, where the Standard Oil headquarters were located. Rockefeller preferred to be pictured at one of his four estates. These included Pocantico Hills in Westchester, New York, a private duchy of more than 3,000 acres overlooking the Hudson River and laced by dozens of miles of winding roads, not to mention a 12-hole golf course for the master. There was also Forest Hill in Cleveland, with its rambling Victorian mansion, splendid views of Lake Erie, half-mile racetrack, two artificial lakes, skating pond, 20 miles of bridle paths, and nine-hole golf course; Golf House in Lakewood, New Jersey, a former country club, discreetly tucked away within 75 acres of spruce, fir, pine, and hemlock trees; and The Casements in Ormond Beach, Florida, where the terraced gardens were ventilated by ocean breezes and tall palms.

Rockefeller's competitive maneuvers seem muscular, even savage, today's more cautious standards, because forged his monopoly before legislation such as the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act outlawed many of the practices that he had perfected. His repertoire of anti-competitive schemes was almost diabolically clever. He colluded with railroads to win special rates, established secret subsidiaries that posed as Standard Oil's foes, developed industrial espionage to high art, and thrashed rivals with steep price cuts, a practice known as predatory pricing.

Oil drillers foolish enough to defy Rockefeller felt his crushing yet invisible force. They might find their oil barred from Standard's pipelines, which monopolized every field, or—if shipping by rail—they might discover a mysterious shortage of tank cars or prohibitive freight rates.

The architect of these astonishing intricacies was an implausible blend of sin and sanctity—a devout Baptist given to Puritan thrift. The self -made Rockefeller, who had risen from neither royalty nor riches, firmly believed that God had blessed the economic rationale behind Standard Oil. Challenging the verities of small-town America in the 19th century, Rockefeller envisioned a new industrial order based on monopolies and trusts instead of competitive struggle. As the prophet of this vision, he sometimes sounded as if he had personally enlisted the Lord among his shareholders.

Frequently stereotyped as a cold curmudgeon, Rockefeller was actually a genial, eccentric man with a droll wit and a fatal passion for cornball stories. If he came to symbolize the best and worst in the American character, it had something to do with his crazily mismatched parents, country folk from upstate New York. His mother, Eliza, was a stern, churchgoing woman who pounded precepts about duty and religion into her son; his father, William, a colorful scamp, was a smalltime con artist and snake-oil peddler. (He deserted the family when John was an adolescent, entering a bigamous second marriage under the pseudonym of Dr. William Levingston.)

John himself would exhibit, in striking relief, his mother's frugal habits and Baptist piety along with his father's canny rascality. The two personalities, lashed together under great pressure, made him the archetypal businessman for a nation torn between its guilty Puritan conscience and its lust for riches.

In the typical business saga, the tycoon amasses money by unscrupulous means, then fumigates the fortune with widely advertised charity. Rockefeller, however, spent a lifetime building up a philanthropic empire no less far-reaching than Standard Oil. Even as a teenage clerk, perched on a stool in a Cleveland commodity house, John Rockefeller had already begun to tithe. By the 1880s, while still in his 40s, he had emerged as the patron of what is now Spelman College in Atlanta, an institution then devoted to educating emancipated female slaves.

A decade later, he bankrolled the University of Chicago, transforming it, almost overnight, into a school comparable to an Ivy League college. In the early 1900s, he sponsored America's first major medical-research institute—now Rockefeller University in Manhattan—followed a decade later by America's foremost philanthropy, the Rockefeller Foundation.

By the early 1900s, Rockefeller's name had become synonymous with money, although his holdings didn't peak until 1913, when he essentially became a billionaire. (After more than $45 million in charitable donations that year, his net worth was actually $900 million. To put this figure in perspective, the accumulated national debt of the United States stood at $1.19 billion that

year—equivalent to 3 percent of the gross national product.) Both figures considerably understate his fortune; he had probably earned at least $2 billion but had given away lavish sums annually. In 1917, two years before his yearly contributions hit the $139 million mark, Rockefeller estimated that, had he invested all he had earned, he would have been worth $3 billion.

As critics carped at his rapacity, Rockefeller was besieged with financial requests from every quarter, including from those who professed to despise him. As if he were Santa Claus, he received up to 50,000 "begging letters" per month. People simply put his picture on envelopes, stamped them, and mailed them; the letters always reached him within days.

In the early 1890s, Rockefeller veered toward a nervous breakdown, less from business burdens than from the excruciating pressures of his charitable commitments. Making matters worse was a devastating personal blow in 1901: a total loss of body hair, a malady known as generalized alopecia. Within months, he was transmogrified from a handsome, rather youthful-looking man into a hairless ghoul. Nearing 60 in the late 1890s, he had decided to retire, play golf, dabble in stocks, croon hymns, and enjoy family gatherings with his wife, Cettie, and their children, who by 1900 had their own lives. (Bessie was 34; Alta, 29; Edith, 28; and John D. junior, 26.)

Whatever his hopes, it was too late for Rockefeller to extricate himself fully from Standard Oil, which was embattled in what would shape up as the fiercest clash between government and a private firm in American history. "These cases against us were pending in the courts," explained one Rockefeller partner, "and we told him that if any of us had to go to jail he would have to go with us!"

Rockefeller, who owned more than one-fourth of all Standard Oil shares, wanted to escape operational responsibility, yet his colleagues insisted that he remain honorary president. "I urged my brother [William] to take this position," Rockefeller later said, "but as he declined ... I was called the president . . . although the position is entirely nominal."

Unbeknownst to the general public, Rockefeller never attended a meeting thereafter and in 1905 even stopped taking a token salary. John D. Archbold, the new vice president, began to run the organization, which was thriving. By the late 1890s, the future for oil and its by-products had never looked brighter. Sales boomed in everything from oil stoves to parlor lamps to varnish, soaking up oil supplies and driving prices skyward.

New petroleum applications more than offset the decline in Standard's kerosene business after the introduction of electricity. In 1903, the British navy outfitted some battleships to use fuel oil instead of coal, attracting the notice of the U.S. Navy. Paraffin wax had become a vital insulator in the burgeoning telephone and electrical industries. Most momentous of all, the automobile promised to consume that once vile, useless by-product, gasoline, and Standard Oil cultivated the new car-makers.

Rockefeller, said his closest associate, "would do me out of a dollar today—if he could do it honestly."

When Henry Ford rolled out his first vehicle, Charlie Ross, a Standard Oil salesman, stood by with a can of the trust's Atlantic Red Oil. The number of registered automobiles in America leapt from 800 in 1898 to 8,000 in 1900. When the Wright brothers took off from Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, in December of 1903, their flight was powered by gasoline brought to the beach by Standard Oil salesmen.

Despite the upsurge in prosperity following the election of President William McKinley in 1896, the electorate grew more and more wary of the so-called trusts which increasingly dictated the fate of one industry after another. These protean combines took many forms— including holding companies, pools, and other creative forms of collusion— but they all shared a common objective: to restrain trade in a given industry, subjecting it to the whims of a single group of men. Since corporations still couldn't acquire stakes in other corporations, their stockholders would transfer their shares to a committee that held them "in trust"; through this legal legerdemain, they were able to control most or all of an industry. Over time, the word "trust" became more or less interchangeable with "monopoly."

Between 1898 and 1902, nearly 200 trusts or giant corporations were cobbled together in industries ranging from steel to coal to sugar. Their monstrous size and inexorable growth prompted a rising clamor from outraged citizens worried about the threat they posed to democracy, the vitality of small-town business, and America's vaunted individualism.

Rockefeller and Standard Oil were reviled with special fury. From the industry's earliest days, their brawny tactics had stirred enmity among oil producers and refiners. Standard's bullying methods created a broad-based constituency for reform in every congressional district.

Enamored of secrecy, Rockefeller was a target tailor-made for anti-trust crusaders and was accused of sins great and small. His clandestine deals with the railroads drew vociferous protests, and he was charged with isolated acts of cruelty and mayhem—such as blowing up a rival refinery in Buffalo and crushing a supposedly defenseless Cleveland widow named Mrs. Backus, who sold her late husband's lubricating plant to Standard Oil.

On October 11, 1898, Rockefeller was summoned to testify at a hearing over charges brought against Standard by the Ohio state attorney general. It was held at Manhattan's New Amsterdam Hotel. Standard's lawyers spent much more time objecting to questions than Rockefeller did answering them. Reporters noted that he kept shifting his weight, crossing and uncrossing his legs, rubbing his nape, blowing out his cheeks, and biting his mustache. The next day's World ran the headline JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IMITATES A CLAM.

Rockefeller's anxiety was not entirely baseless. After a young anarchist assassinated William McKinley in Buffalo in September 1901, there were widespread fears of a broader conspiracy. In Chicago, reporters learned of a conversation in which both financier J. P. Morgan and Rockefeller were mentioned as potential targets.

As it turned out, however, the gravest threat to the titan's welfare emanated from 43-year-old Theodore Roosevelt, who succeeded McKinley in 1901.

Roosevelt, whom Rockefeller considered "the shrewdest of politicians," was descended from Dutch settlers who immigrated to New Amsterdam before 1648 and later made a fortune in Manhattan real estate. Like many of his social peers, the cultivated new president was scandalized by the sordid ethics of the new industrial class.

As a New York State assemblyman in 1883, this aristocratic renegade berated financier Jay Gould and his ilk as members of "the wealthy criminal class.

The misgivings of those who feared Teddy Roosevelt as a trustbuster were actually somewhat exaggerated. Roosevelt distinguished between bad trusts, which gouged consumers, and good trusts, which offered fair prices and good service. Rather than beginning a wave of indiscriminate trust-busting, he concentrated on the worst offenders, singling out the Rockefeller empire.

In stalking Standard Oil, Roosevelt had no more potent ally than the American press, and, with advertising on the upswing, many periodicals were swelling in size. Aided by new technologies, including Linotype and photoengraving, spiffy illustrated magazines streamed forth in such numbers that the era would be memorialized as the golden age of the American magazine. Paralleling this was the rise of mass-circulation newspapers, which catered to an expanding reading public. Joseph Pulitzer, William Randolph Hearst, and other press barons plied readers with both scandals and crusades, while the more sophisticated publications tackled complex stories and promoted them aggressively.

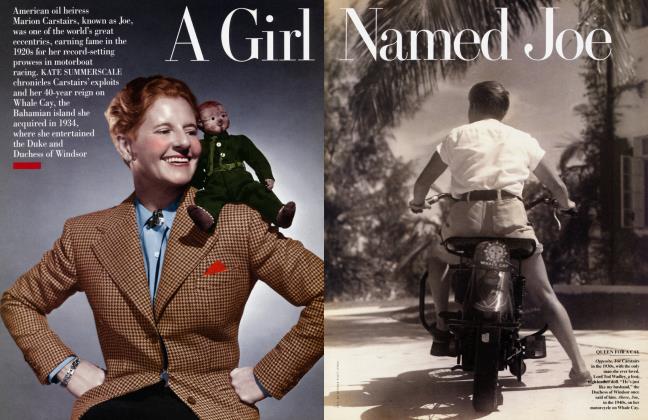

Studded with star writers and editors, the most impressive periodical was McClure's Magazine, a monthly started by Samuel S. McClure in 1893, which managed to outdistance competitors such as Colliers, Leslie's, and Everybody's. In September 1901, the same month that Roosevelt ascended to the presidency, the magazine's managing editor, Ida Minerva Tarbell, sailed to Europe to confer with McClure, who was then in Vevey, Switzerland, taking a rest. In her suitcase Tarbell carried an outline for a threepart series on Standard Oil, though she wondered whether anyone would ever wade through it.

The Standard Oil story was intertwined with Ida Tarbell's early life. Born in 1857 in a log cabin 30 miles from where Drake would strike oil two years later, she was a true daughter of oil country. "I had grown up with oil derricks, oil tanks, pipelines, refineries, and oil exchanges," she wrote in her memoirs. Her father, Franklin Tarbell, crafted vats from hemlock bark, a trade easily converted into barrel-making after Drake's discovery. The Tarbells lived beside his Rouseville barrel shop, and as a child Ida rolled luxuriously in heaps of pine shavings.

"We have to be patient," Rockefeller told his son. "We have been successful and these people haven't."

In 1865, Ida watched men with queer gleams in their eyes swarming through Rouseville en route to the miracle turned mirage of Pithole, Pennsylvania. Franklin Tarbell set up a barrel shop there and cashed in on the craze before Pithole's oil gave out. He then sought his fortune as an independent oil producer and refiner, just as Rockefeller was snuffing out small operators.

In 1872, as an impressionable 15-yearold, Ida saw her paradise torn asunder by the South Improvement Company (S.I.C.), a conspiracy that Rockefeller had hatched with the railroads to drive the small local refiners of western Pennsylvania out of business. As her father joined vigilantes who sabotaged the conspirators' tanks, she thrilled to the talk of revolution. "The word became holy to me," she later wrote.

She remembered the Titusville of her teenage years as a place divided between the valiant majority who resisted "the Octopus" and the small band of opportunists who defected to it. "In those days I looked with more contempt on the man who had gone over to the Standard than on the one who had been in jail," she said.

Although Ida Tarbell, raised as a Methodist, had more books, magazines, and small luxuries than the youthful John Rockefeller, one is struck by the similarity of their households. Like the Baptist Rockefellers of John's childhood, the straitlaced Franklin Tarbell forbade cards and dancing and supported many causes, including temperance. Ida attended prayer meetings and taught an infant class at Sunday school. Shy and bookish, she tended, like Rockefeller, to arrive at brilliant solutions by slow persistence.

What set Tarbell apart from Rockefeller was her intellectual daring and fearless curiosity. As a teenager, despite her family's fundamentalism, she tried to prove the truth of evolution. In 1876, when she enrolled at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania, she was the sole girl in the freshman class.

She loved to peer through microscopes and planned to become a biologist. But after graduation Ida Tarbell taught for two years, then got a job in Meadville on the editorial staff of The Chautauquan, an offshoot of the summer adult-education movement, which had originated as a Methodist camp meeting. The fiery Christian spirit of her peers made the young woman even more high-minded.

Tall and attractive, with dark hair, large gray eyes, and high cheekbones, Ida Tarbell had an erect carriage and innate dignity and never lacked suitors. Yet she decided never to marry and would remain self-sufficient throughout her career.

In 1891, the 34-year-old moved to Paris with friends and set up bohemian quarters on the Left Bank. She was determined to write a biography of the Girondist Madame Roland while selling freelance articles and attending classes at the Sorbonne. She mailed off two articles during her first week in Paris alone. While she was in France, Tarbell interviewed Louis Pasteur and Emile Zola, and won admirers. Still, she struggled on the "ragged edge of bankruptcy" and was susceptible when McClure wooed her in 1892 as a writer for his new magazine.

Two events that occurred while the young woman was still in Paris would help lead her to Standard Oil. One Sunday afternoon in June 1892, she read in Paris newspapers that Titusville and Oil City had been ravaged by flood and fire, with 150 people killed. The next day, her brother William Walter Tarbell's single-word cable—"Safe"—relieved her anxieties, but not her regrets over leaving her family.

The next year, one of Tarbell's father's oil partners shot himself in despair over poor business, forcing Franklin Tarbell to mortgage his house. Ida's sister was in the hospital at the time, and "here was I across the ocean writing picayune pieces at a fourth of a cent a word," the journalist later recalled. "I felt guilty." Around this time, Tarbell laid her hands on a copy of the first expose of Rockefeller, Wealth Against Commonwealth, published in 1894 by Henry Demarest Lloyd. Here she rediscovered the author of her father's woes: John D. Rockefeller.

Back in New York in 1894, Tarbell published two biographies in McClure's in serial form. These may have helped further her interest in Rockefeller. The presented Napoleon as a gifted megalomaniac, a great man lacking "that fine sense of proportion which holds the rights of others in the same solemn reverence which it demands for its own." By the end of the series, McClure's circulation had leapt from 24,500 to 100,000.

Next came Tarbell's celebrated 20part series on Abraham Lincoln, which absorbed four years of her life (1895-99) and boosted the magazine's circulation to 300,000. She honed her investigative skills as she excavated dusty documents and courthouse records. In 1899, after being named managing editor of McClure's, Tarbell took an apartment in Greenwich Village and befriended literary notables including Mark Twain.

Having sharpened her craft, Tarbell was set to publish one of the most influential pieces of journalism in American business history. The idea of dissecting Standard Oil had fermented in her mind for a long time. "Years ago ... I had planned to write the great American novel, having the Standard Oil Company as a backbone!"

Her experiences as a reporter made her realize that the facts were better than anything she could make up. After receiving McClure's blessing, Tarbell launched her Standard Oil series in November 1902, feeding the American public rich, monthly servings of Rockefeller's past misdeeds. She went back to the early Cleveland days and laid out the whole story of his evolution for careful inspection. All the depredations of a long career, everything Rockefeller had thought safely buried and forgotten, rose up before him in haunting and memorable detail.

"If I had met him on the street, I know that I should have shot him," Frank Rockefeller said of his brother John.

Tarbell was encouraged by Samuel McClure, one of the most inspired windbags ever to occupy an editor's chair. High-strung, seized by hourly brainstorms, McClure was described by Rudyard Kipling as a "cyclone in a frock coat." Moving frenetically, he seemed forever lurching toward nervous collapse. "Able methodical people grow on every bush but genius comes once in a generation and if you ever get in its vicinity thank the Lord & stick," Tarbell advised.

McClure would collar every talented young writer in America—Frank Norris, Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser, and Willa Cather—as well as more established figures, such as Mark Twain, Kipling, O. Henry, Damon Runyon, and Booth Tarkington. Yet it was in journalistic nonfiction that McClure left his lasting imprint.

A man with a weakness for startling facts, McClure wanted to analyze complex issues with scientific precision. Aiming at a comprehensive critique of American society, he concluded by 1901 that two great issues confronted the country: the growth of industrial trusts and political corruption. Before long, Lincoln Steffens was digging out municipal corruption in "The Shame of the Cities," which began in McClure's in October 1902 and ran for seven installments.

The country's finest investigative reporters gradually made their way to the magazine. One of them, Ray Stannard Baker, called it "the most stimulating, yes intoxicating editorial atmosphere then existent in America—or anywhere else."

Tarbell had contemplated exposing the steel and sugar trusts before the discovery of oil in California turned her attention to Standard Oil as the "most perfectly developed trust." Since the company had been investigated by various government bodies for three decades, there was a long documentary trail. At first projected to run over three successive issues, the Standard Oil series eventually stretched, by popular demand, to 19 installments. It was inaugurated in November 1902 against an especially timely backdrop: an anthracite-coal strike during the winter of 1902-3 deprived the poor of coal, forcing them to heat their homes with oil. The subsequent rise in oil prices created an incendiary issue.

Although Tarbell pretended to apply her scalpel with surgical objectivity, she was never neutral, and not only because of her father. Her brother William had been a leading figure in forming the Pure Oil Company, the only serious domestic challenger to Standard Oil, and his letters to her were tinged with anti-Standard venom. As Pure Oil's treasurer in 1902, Will steered legions of Rockefeller's enemies to his sister and even vetted her manuscripts. Amazingly, nobody made an issue of Tarbell's objectivity—or motives.

When Franklin Tarbell heard that his daughter was eyeing Standard, he warned of extreme danger. "Don't do it, Ida—they will ruin the magazine," he said, hinting as well that Rockefeller might have her maimed or murdered. But she kept on.

As Tarbell's research began, a sentimental trip to Titusville almost certainly rekindled her animosity toward her subject. Her father's terminal illness—Franklin had stomach cancer-may have further embittered her.

During the course of Tarbell's reporting, Standard Oil remained haughtily silent, and the closest the reporter came to being threatened during the project was at a Washington dinner party. Frank Vanderlip, a vice president of National City Bank, drew her into a side room to voice his strong displeasure with her work. Ignoring her sense of some vague financial menace to McClure's, she retorted, "Well, I am sorry, but of course that makes no difference to me."

Tarbell approached her work methodically, like a carpenter, but she soon reeled under the weight of the interviewing and research. After a week of combing through reports from the Industrial Commission in February 1902, she wrote despairingly, "The task confronting me is such a monstrous one that I am staggering a bit." By June, having completed three installments, she confessed that the material had acquired an obsessive hold over her. On the eve of a needed holiday in the Alps, she told her research assistant, "It has become a great bugbear. ... I dream of the octopus by night and think of nothing else by day."

Upon her return, she met with Henry Demarest Lloyd, the eloquent, reformminded author of Wealth Against Commonwealth, at his seaside estate in Sakonnet, Rhode Island. He told her, barely containing his rage, that Rockefeller and his associates embodied "the most dangerous tendencies in modern life." Later, when he learned that she had met with Henry H. Rogers, one of the chief executives at Standard Oil, Lloyd thought Tarbell might be in cahoots with the company and warned his contacts to watch out. But his doubts were dispelled when the series got under way. "When you get through with 'Johnnie,' " he told her in April 1903, "I don't think there will be very much left of him except something resembling one of his own grease spots."

Shortly before Tarbell began her research, McClure had tried to coax Mark Twain into editing a new magazine, but Henry Rogers, a close friend, persuaded Twain to resist. Rogers, who had spotted an ad announcing the forthcoming Standard Oil series, was startled that nobody there had been contacted by Tarbell. Concerned, he wrote Twain that "any person desiring to write a veritable history would seek for information as near original sources as possible." When Twain confronted McClure, the editor balked, saying, "You will have to ask Miss Tarbell." To which Twain replied, "Would Miss Tarbell see Mr. Rogers?" She couldn't resist the opportunity.

A veteran charmer, "Hell Hound" Rogers, as he was known on Wall Street, invited Tarbell for a two-hour chat at his home on East 57th Street. Having never met a real captain of industry before, the reporter was entranced. "His big head with its high forehead was set off by a heavy shock of beautiful gray hair; his nose was aquiline, sensitive," she wrote years later.

Tarbell agreed to give Rogers a chance to react to any revelations she unearthed, and for two years she periodically visited him at 26 Broadway. These encounters had a quasi-clandestine aura, with the reporter whisked in one door and out another. Tarbell spoke with the executive for nearly a year before the series started and held her breath when the first installment appeared. "I rather expected him to cut me off." But to Tarbell's astonishment Rogers continued to receive her, and, while occasionally miffed by this or that article, he remained on friendly terms with her.

Rogers's complaisance has always been a huge mystery, engendering two schools of thought. Tarbell cited the executive's selfinterest; she believed that he was willing to see Standard Oil's reputation sullied if his own was preserved. He and John Archbold had been stung by accusations that they had conspired to blow up the Buffalo refinery. "That case is a sore point," he told Tarbell. "I want you to go into it thoroughly."

Other observers hypothesized that Rogers was deflecting attention from his own misdeeds and taking revenge on Rockefeller, who privately denounced Rogers as a traitor. Tarbell's notes reveal that Rogers often defended Rockefeller while also carefully keeping the spotlight on his boss.

Rogers terminated his meetings with Tarbell in February 1904, when she published a shocking account of railway agents spying on Standard Oil competitors—a practice that Rogers had strenuously denied. When she next arrived at 26 Broadway, he demanded, "Where did you get that stuff?" That tense meeting ended their relationship.

While stewing about Rogers, Rockefeller would have been equally shocked and wounded had he heard the acidulous comments made to Ida Tarbell by his old pal Henry M. Flagler, a co-founder of Standard Oil back in 1870 and his closest business associate. Tarbell was taken aback when Flagler portrayed the titan as petty and miserly. Tarbell noted, "Mr. Flagler talked to me of J.D.R. Says he is the biggest little man and the littlest big man he ever knew. That he would give $100,000 one minute to charity and turn around and haggle over the price of a ton of coal. Says emphatically: 'I have been in business with [Rockefeller] 45 years and he would do me out of a dollar today—that is, if he could do it honestly.' "

The subject of this description saw no need to speak to the reporter from McClure's. Rockefeller, who had no notion that Tarbell could wield her slingshot with such deadly accuracy, had weathered 30 years of assaults in courts and statehouses. He must have felt invulnerable. When associates clamored for a response to Tarbell, Rockefeller replied, "Gentlemen, we must not be entangled in controversies. If she is right, we will not gain anything by answering, and if she is wrong, time will vindicate us."

From the perspective of nearly a century later, Ida Tarbell's series remains the most impressive thing ever written about Standard Oil—a tour de force of reportage that dissects the trust's machinations with withering clarity. Her careful chronology provided a trenchant account of how the combine had evolved, and made the convoluted history of the oil industry comprehensible. In the dispassionate manner associated with McClure's, she sliced open America's most secretive business and showed all the hidden gears and wheels turning inside it. Her relatively cool style made readers boil.

Like Teddy Roosevelt, Tarbell did not condemn Standard Oil for its size—only for its abuses. She did not argue for the automatic dismantling of all trusts, and pleaded only for the preservation of free competition. While by no means evenhanded, Tarbell was quick to acknowledge the genuine achievements of Rockefeller and his cohorts and even devoted one article to "The Legitimate Greatness of the Standard Oil Company." She wrote, "There was not a lazy bone in the organization, not an incompetent hand, nor a stupid head." What most exasperated her was the fact that these intelligent men could have succeeded honestly. "They had never played fair," she wrote, "and that ruined their greatness."

It was in the trust's collusion with the railroads—the intricate and highly developed system of rebates, drawbacks, and other forms of favoritism—that Tarbell found her irrefutable proof that Rockefeller's empire had been built by devious means. She took pains to contradict the titan's defense that everybody practiced such collusion. "Everybody did not do it," she protested indignantly. "In the nature of the offense everybody could not do it. The strong wrested from the railroads the privilege of preying upon the weak."

Tarbell argued that Rockefeller had succeeded by imbuing subordinates with a ferocious desire to win at all costs. "Mr. Rockefeller has systematically played with loaded dice, and it is doubtful if there has ever been a time since 1872 when he has run a race with a competitor and started fair." Tarbell rightly surmised that Standard Oil received secret kickbacks from the railroads on a more elaborate scale than its rivals.

Tarbell showed that Rockefeller had taken over some refineries in an orchestrated atmosphere of intimidation. She exposed the deceit of an organization that operated through a maze of hidden subsidiaries in which connections to Standard Oil were kept secret from all but the highest-ranking employees. She sketched out many abuses of power, including how the company, through its monopolization of the pipelines, subdued refractory producers while favoring Standard's own refineries. And she chronicled the terror tactics by which the trust's marketing subsidiaries got retailers to stock their products exclusively. She also decried the trust's threat to democracy and the subornation of state legislators, but never guessed the depths of corruption now revealed by Rockefeller's papers.

Nevertheless, as historian Allan Nevins and other defenders of Rockefeller pointed out, Tarbell committed numerous errors. The most celebrated and widely quoted charge that Tarbell made against Rockefeller was the least deserved: that he had robbed Mrs. Fred M. Backus—forever known to history as "the Widow Backus"—blind when buying her Cleveland lubricating plant in 1878. "If it were true," Rockefeller later conceded, it "would represent a shocking instance of cruelty in crushing a defenseless woman." He added that the story had "awakened more hostility against the Standard Oil Company and against me personally than any charge which has been made."

To recount the Backus case in brief: Mrs. Backus had valued her operation at between $150,000 and $200,000 and hotly told any reporter who would listen that Standard Oil had cheated her by paying $79,000. Rockefeller mocked the plant as antiquated and poorly situated and argued that he could build new, more modern facilities for less money. As it happened, Mrs. Backus's own negotiator, Charles H. Marr, later swore that his client had valued her plant at a figure only slightly higher than the ultimate purchase price. Far from being doomed to Dickensian misery, the Widow Backus invested her proceeds in Cleveland real estate and died a rich woman.

Tarbell, however, had the honesty to debunk another story, specifically that Rockefeller had blown up a competing refinery in Buffalo. (It was this allegation that had so upset Henry Rogers.) Constantly brandished by Joseph Pulitzer's highly sensational New York newspaper, the World, the tale was a perennial of the anti-Standard Oil literature.

But, despite Tarbell's careful analysis of that incident—enriched perhaps by material from Henry Rogers—she was vulnerable to criticism of other, broader dimensions, namely that she was swayed by her childhood memories. She excessively ennobled the oil drillers from her home state of Pennsylvania, portraying them as exemplars of a superior morality. "They believed," she wrote, "in independent effort—every man for himself and fair play for all. They wanted competition, loved open fight."

To support this romantic vision, Tarbell had to overlook the baldly anti-competitive agreements proposed by the producers themselves. Far from being free-marketeers, they repeatedly tried to form their own cartels to restrict output and boost prices. And, as Rockefeller pointed out, they happily took rebates whenever they could. The world of the early oil industry was not, as Tarbell implied, a morality play of the evil Standard Oil versus the brave, noble independents of western Pennsylvania, but a harsh dog-eat-dog world.

One of the first and most shocking revelations dug up by Tarbell and her research assistant, John Siddall, came from a teenage boy who had been assigned to burn records at a Standard Oil plant each month. He was about to incinerate some forms one night when he noticed the name of his former Sunday-school teacher, who was an independent refiner and Standard Oil rival. Leafing through the documents sent for burning, he realized that they were secret records, obtained from the railroads, detailing the shipments of rival refiners. Tarbell knew Standard Oil was ruthless, but she was shocked by this outright criminal activity.

Yet the team of journalists was willing to take its own moral shortcuts to expose Rockefeller. To spy on the millionaire, Siddall had a friend from the Cleveland Plain Dealer impersonate a Sunday-school teacher in order to sneak into the annual church picnic at Forest Hill, the Rockefellers' Cleveland estate. At Siddall's behest, an old Rockefeller friend, Hiram Brown, pumped the unwitting mogul on several matters (including his reaction to the McClure's series).

Since Rockefeller banned Tarbell from his presence, Siddall searched for a way to obtain a firsthand glimpse. During summers spent at Forest Hill, Rockefeller appeared in public only for services at the Euclid Avenue Baptist Church. By the early 1900s, this event had taken on the air of a circus spectacle as hundreds of people massed outside the church to view him. As the Tarbell series swelled the gaping throngs, Rockefeller would gingerly approach his church bodyguard before the service and ask, "Are there any of our friends, the reporters, here?" Sometimes, he confessed, he wanted to bolt from the service, but he feared that people would brand him a coward. At one Friday-evening prayer service, Rockefeller grew rattled when a radical agitator sat opposite him all evening, his hand stuffed menacingly in his pocket.

It probably hurt Rockefeller's image that he appeared in public only at church, for it played to the stereotype of a hypocrite cloaking himself in sanctity. In fact, his motivation for churchgoing—beyond the spiritual comfort of prayer—was quite simple: he relished the contact with ordinary people, many of them old friends. The church retained many blue-collar members, enabling Rockefeller to chat amiably with a blacksmith or a mechanic. Such everyday experiences increasingly eluded him as he withdrew behind the high gates of his estates.

On Sunday, June 14, 1903, John Siddall got a windfall beyond his most feverish hopes when Rockefeller, just a month short of his 64th birthday, not only appeared but delivered a short "Children's Day" talk at the Sunday school. "If I had been able to foretell what happened yesterday I should have advised you to come from Titusville to spend Sunday in Cleveland," Siddall told Tarbell. Tarbell's assistant described Rockefeller, in ministerial coat and silk hat, sitting before the pulpit and surveying the crowd apprehensively, as if fearful for his safety. "He bows his head and mutters his prayer, and sings the hymns, and nods his head, and claps his hands in a sort of a mechanical way. It's all work to him—a part of his business. He thinks that after he has done this for an hour or two he has warded off the devil for another week."

Only months later did Siddall learn of the anonymous charity Rockefeller practiced each Sunday morning, handing out money in small envelopes to needy congregants. "Doesn't this shake your belief in the theory of pure hypocrisy?" Siddall asked Tarbell. He noted the curiously compartmentalized nature of Rockefeller's mind. "In one part is legitimate business, in another corrupt business, in another personal depravity, in another—somewhere in his being-religious experience and life."

In the early fall, Siddall found out that Rockefeller, before returning to New York, would deliver a short farewell address at the Sunday school, and the eager researcher begged Ida Tarbell to attend. "I will see that we have seats where we will have a full view of the man," he promised her. "You will get him in action."

On the day itself, the observers succeeded in squeezing between them an illustrator, George Varian, who executed a rapid sketch of Rockefeller, which subsequently appeared in McClure's. Tarbell felt "a little mean" about secretly ambushing Rockefeller in church, and she dreaded being caught. To prevent this, she asked Siddall to pack the pew in front of them with three or four tall confederates who would shield Varian and his notebook.

When Tarbell and Siddall arrived at the Sunday-school room that morning, she wrinkled her nose at the shabby surroundings, "a dismal room with a barbaric dark green paper with big gold designs, cheap stained-glass windows, awkward gas fixtures." Suddenly, Siddall gave her a violent dig in the ribs. "There he is," he breathed.

The hairless figure in the doorway did not disappoint Tarbell. As she wrote, "There was an awful age in his face—the oldest man I had ever seen, I thought, but what power!" He slowly took off his coat and hat, slid a black skullcap over his bald head, and sat flush against the wall, where he had an unobstructed view of the room. (Tarbell believed he made his choice of seating for security reasons.) During his brief talk to the children, she was impressed by the clear strength of his voice. After the Sundayschool speech, the McClure's contingent packed a church pew in the auditorium for the service. Self-conscious about being there, Tarbell was convinced that Rockefeller would pick her out of the crowd, but he apparently did not.

Despite her fears, Tarbell and her associates evaded detection at the Euclid Avenue Baptist Church that Sunday morning. It was the only time that Tarbell was ever actually in Rockefeller's presence. Ironically, he never knowingly set eyes on the woman who did more than any other person to tarnish his image.

Though billed as a history of Standard Oil, the Tarbell series presented Rockefeller as the protagonist. She made Standard Oil and Rockefeller interchangeable, even when covering the period after Rockefeller retired. This great-man approach to history gave a human face to the gigantic, amorphous entity known as Standard Oil, but also turned the full force of public fury on Rockefeller, who became the most hated man in America. It did not acknowledge the bureaucratic reality of Standard Oil, with its labyrinthine committee system, and stigmatized Rockefeller to the exclusion of his associates. Flagler emerged relatively unscathed, even though he had negotiated most of the secret freight contracts that loom so large in the McClure's expose.

By the third installment of Tarbell's series, in January 1903, President Roosevelt himself sent her a flattering note. Tarbell's celebrity spread with each issue. "The way you are generally esteemed and reverenced pleases me tremendously," McClure told her. "You are today the most generally famous woman in America."

Samuel McClure would let a series run as long as the public snatched up copies. The Standard Oil saga profited from a tremendous crescendo of attention, which drew more and more Rockefeller critics from the woodwork. The circulation of McClure's had risen to 375,000 by the time Tarbell's 19-part series was finished. Though it was published as a two-volume book in November 1904, she then capped it with a scathing two-part character study of Rockefeller in McClure's in July and August of 1905.

In the study, Tarbell stressed Rockefeller's fidgety behavior, the way he had craned his neck and scanned the church that Sunday morning, as if searching for assassins. This was vitally important for Tarbell: it suggested that Rockefeller had a guilt-ridden conscience, that he could not enjoy his ill-gotten wealth. "For what good this undoubted power of achievement, for what good this towering wealth, if one must be forever peering to see what is behind!" It never occurred to Tarbell that Rockefeller might be searching the congregation for charity recipients.

Throwing off any semblance of objectivity, she found in Rockefeller "concentration, craftiness, cruelty, and something indefinably repulsive." She described him as a "living mummy," hideous and diseased, leprous and reptilian, his physiognomy blighted by moral degeneracy. The pious, churchgoing image that Rockefeller projected was only a "hypocritical facade brilliantly created."

Rockefeller could brush off Tarbelfs critique of his business methods as biased, but he was deeply pained by the character study. He was furious that Tarbell converted his alopecia, which had produced so much suffering, into a sign of moral turpitude. He was no less upset by her charge that he was ill at ease in his church, for this struck at the heart of his lifelong faith. As he later said, he was not fearful in church, "because there was no place where I felt more at home in a public assembly than in this old church, where I had been since a boy of fourteen years and my friends were all about me."

A mong the legions of Rockefeller enemies who had interviews with Tarbell was the mogul's most vituperative foe, Frank Rockefeller, his envious, disgruntled younger brother. Frank had never forgiven John after the titan refused to extend a loan made to one of his brother's close friends. Frank popped up in the press from time to time to deliver flaming imprecations against John. But Frank had not set eyes on his brother in years and knew only gossip.

Tarbelfs breakthrough with Frank occurred in January 1904, when Siddall learned that the Tarbell series had won two unexpected admirers: Frank's daughter and son-in-law Helen and Walter. Using the latter as a go-between, Frank stipulated his conditions for a tete-a-tete with Tarbell in Cleveland: "I want no member of my family to know of this interview. ... I shall see Miss Tarbell in my Garfield Building office. No one is to be present. No clerk is to know who Miss T is."

Following instructions, Tarbell even concocted a disguise for what would be one of the most disturbing interviews of her long career. Frank seemed candid as he chewed tobacco, but talked incontinently, spewing forth bile against his brother. At moments, his self-pitying harangues suggested a deranged man.

Unaware of the stormy history between the two brothers, Tarbell was appalled by the ugly emotions that Frank betrayed. But she welcomed his information. Frank portrayed John in a lurid, distorted light as a sadist who took pleasure in lending people money, then seizing their collateral and destroying them when they did not repay: "Cleveland could be paved with the mortgages that he has foreclosed on people who were in a tight place."

Frank contributed few revelatory facts but vented his spleen. He told Tarbell that John had only two ambitions—to be very rich and very old—and even chastised his brother's wife, the former Laura Celestia Spelman, known as Cettie, calling her a "narrow-minded, stingy and pious" woman, whose greatest goal was "to be known as a good Christian, and to impress the world with the piety and domestic harmony of the family."

Touching up this gruesome portrait, Frank later added: "[John] has the delusion that God has appointed him to administer all the wealth in the world, and in his efforts to do this he has destroyed men right and left. I tell you that when you publish this story the people will arise and stone him out of the community. ... He is a monster."

Frank's Finale to his ravings about his brother shocked even Tarbell. "I know you think I am bitter and that it is unnatural, but this man has ruined my life. Why I have not killed him I do not understand. It must be that there is a God who prevented me doing such a thing, for there have been a hundred times when, if I had met him on the street, I know that I should have shot him." But Frank did not mention that John had bailed him out of bankruptcy several times.

Such lunacy should have warned Tarbell to exercise extreme care with information gleaned from this volatile source. Instead, in a lapse of judgment, she used Frank's material in such a slipshod, misleading manner that John justly accused her of slanting the story.

Tarbell never knew about Frank's hypocritical reliance on his brother's generosity. Unable to curb his speculative appetite, Frank took an emergency loan of $184,000 from his brother William during the 1907 Wall Street panic. What Frank did not know—but surely must have suspected—was that John, who had already loaned him so much, had guaranteed half the loan. In fact, John carried the debt until Frank died. In early 1912, however, when Frank again sounded off about his brother to reporters, John dispatched a lawyer to inform the ungrateful Frank about the true source of the money that had sustained him.

TT'or nearly three years, from November X1 1902 to August 1905, Ida Tarbell launched projectiles at Rockefeller and Standard Oil without taking fire in return. As one newspaper speculated, "Is the pen mightier than the money-bag ... Is Ida M. Tarbell, weak woman, more potent than John D. Rockefeller millionaire?" At moments, Tarbell herself was startled by this kid-glove treatment.

From today's perspective, when corporations have teams of publicists who swing into action at the first whiff of trouble, Standard Oil's muted reaction appears to be a perplexing miscalculation. Tarbell got enough wrong that a modern publicrelations expert could have dented her credibility and shaken Samuel McClure with the threat of a libel suit.

So why did Rockefeller stick to his selfdefeating silence? One side of him simply did not want to be bothered by libel suits. "Life is short," he wrote to a friend, "and we have not time to heed the reports of foolish and unprincipled men." He was also afraid that if he sued for libel it would dignify the charges against him and only prolong the controversy. Strolling about Forest Hill with Rockefeller, a friend suggested that he respond to the Tarbell series. At that moment, Rockefeller spotted a worm crawling across their path. "If I step on that worm I will call attention to it," he said. "If I ignore it, it will disappear."

But the main reason for Rockefeller's silence was that he couldn't dispute just a few of Tarbelfs assertions without admitting the truth of many others, and a hard core of truth lay behind the scattered errors. Tarbell herself reached this conclusion in McClure's: "His self-control has been masterful—he knows, nobody better, that to answer is to invite discussion, to answer is to call attention to the facts in the case."

Rockefeller claimed that he had not even deigned to glance at McClure's, a claim inadvertently refuted by Adel la Prentiss Hughes, Cettie's nurse and companion, who traveled with the Rockefellers on a western train trip in the spring of 1903. "He liked to have things read to him, and during these months I read aloud Ida Tarbell's diatribes," she recalled. "He listened musingly, with keen interest and no resentment." He tossed out wisecracks about "his lady friend" Tarbell.

Nonetheless, it is true that Rockefeller never formally sat down and read her searing indictment. "I don't think I ever read Ida Tarbelfs book: I may have skimmed it," he said a decade later. "I wonder what it amounts to, anyway, in the minds of people who have no animus?"

Rockefeller's private comments about his Boswell were marked by a dry mockery that he never revealed in public. "How clever she is," he noted. "She makes her picture clear and attractive, no matter how unjust she is." With friends he referred to the reporter who plagued him as "Miss Tarbarrel."

Far from making Rockefeller repent and reconsider, the Tarbell series hardened his faith in his career. How dismayed Tarbell would have been to find the titan writing to his successor, John Archbold, in July 1905: "I never appreciated more than at present the importance of our taking care of our business—holding it and increasing it in every part of the world."

The press was rife with speculation about Rockefeller's reaction to his nemesis. "Mr. Rockefeller's friends say that it is all cruel punishment for him, and that he writhes under these attacks," reported one Detroit newspaper. A Philadelphia paper chimed in that "the richest man in the world sits by the hour at Forest Hill, his chin sunk on his breast. ... He has lost interest in golf; he has become morose; never free in his conversation with his employees, he now speaks only when absolutely necessary, and then gives his directions tersely and absently." These reports tell more about the popular thirst for revenge than about Rockefeller's actual response. He was never tormented by guilt and never curtailed his golf.

Rockefeller's children had to fall back upon a reflexive belief in their father's integrity. During this period, the titan grew closer to his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., who became his confidant just as Cettie's health, which had grown uncertain, made it more difficult for her to discharge that function. John junior—whom historians would refer to simply as Junior—remembered, "He used to talk to me about the criticisms to which he was exposed, and I think it eased his mind to do so, because beneath his apparent insensitiveness, he was a sensitive man, but he always ended up by saying: 'Well, John, we have to be patient. We have been successful and these people haven't.' "

Rockefeller's decision to refrain from specific rebuttals tormented his son, who had taken his parents' morality at face value. Junior had always been prey to tensionrelated symptoms, and they intensified with each new installment of McClure's. By late 1904, gripped by migraine headaches and insomnia, he wavered on the edge of a breakdown. Under doctor's orders, he, his wife, Abby, and their baby daughter sailed to Cannes in December 1904 for what would extend into a yearlong absence from 26 Broadway. They toured the charming Languedoc country towns, drove through the Maritime Alps, and ambled along the Promenade des Anglais in Nice. But Junior's troubles were so intransigent that their projected one-month stay lengthened to six. Junior's breakdown has been variously attributed to overwork, exhaustion, and an identity crisis, but he himself privately emphasized the toll of the Tarbell series.

While Tarbell's articles were running, Rockefeller, his wife, his son, and two of his three daughters were afflicted by serious medical problems or nervous strain. In 1903, Rockefeller himself had such severe bronchial troubles that he took a rest cure near San Diego. That spring, his eldest daughter, Bessie, suffered a stroke or heart ailment that left her sadly demented, and the following April, her husband, Charles Strong, took off with her for Cannes, where she and Junior may have consulted the same nervous-strain specialist. In April 1904, Cettie, the declining matriarch, had an attack that left her semi-paralyzed and from which she took two years to recover. Finally, plunged into depression after the birth of her youngest child, Mathilde, in April 1905, Edith, Rockefeller's youngest daughter, fled to Europe. Understandably, the Rockefellers did not wish to broadcast their misfortunes to the world. The price that the series exacted from them, like so much else, was scrupulously hidden from the public and posterity.

The McClure's expose inflicted far more than just emotional damage on Rockefeller. It appeared just as Teddy Roosevelt was scouting the horizon for an especially notorious combine to prosecute under the Sherman Antitrust Act. Tarbell's stunning indictment virtually guaranteed that Standard Oil would be the central target of a federal trust-busting probe.

On November 18, 1906—a mere 15 months after Tarbell's character study of Rockefeller appeared—the federal government filed an anti-trust suit against Standard Oil of New Jersey (the holding company), 65 companies under its control, and a pantheon of powerful chieftains, including John and William Rockefeller, Henry Flagler, John Archbold, and Henry Rogers. They were charged with monopolizing the oil industry and conspiring to restrain trade through a litany of tactics already made infamous by Ida Tarbell: railroad rebates, the abuse of the pipeline monopoly, predatory pricing, industrial espionage, and the secret ownership of ostensible competitors. The proposed remedy was sweeping: to break up the massive combine into its component companies.

On May 15, 1911, the Supreme Court upheld an earlier court decision and ordered the dissolution of Standard Oil. The trust was given six months to spin off its subsidiaries as separate companies, with its officers forbidden to re-establish the monopoly. The longest-running morality play in American business history ended with the dismemberment of Standard Oil after 41 turbulent years of ruling the industry. And the catalyst had been the steady, cogent, luminously intelligent reportage of Ida Minerva Tarbell, who had fearlessly torn the veil from America's most mysterious and reclusive businessman.

For Tarbell, the Standard Oil series was her valedictory at McClure's. After a lacerating feud with McClure over business matters, she resigned in 1906, spending the next nine years as editor of American Magazine. Mellowing with age, she not only found much to admire in American business, but developed unexpectedly cordial relations with John D. Rockefeller Jr. when they served together on an industrial conference convened by Woodrow Wilson in 1919. "Personally I liked her very much," Junior said of Tarbell, "although I was never much of an admirer of her book." Tarbell reciprocated this fondness, telling a friend, "I believe there is no man in public life or in business in our country who holds more closely to his ideals than does John D. Rockefeller, Jr. In fact, I will go so far as to say I do not know of any father who had given better guidance to a son than has John D. Rockefeller." In 1925, the aging, more conservative Tarbell published a laudatory biography of Judge Elbert H. Gary of U.S. Steel, followed in 1932 by a favorable life of Owen D. Young of General Electric. Yet whatever the softening influence of the years, she never regretted her expose of Rockefeller or recanted a word of it. True to her vow, she remained unmarried until she died in 1944.

Rockefeller gave way to many lonely moments after Cettie's death in 1915. But he would grow more ebullient with time. Though he lived a solitary life in many ways—Bessie had died in 1906, Edith was in Switzerland or Chicago, and Junior was busy disposing of the family fortune—the old man seemed lighter, more at ease than in previous years. Rockefeller's romance with the southern latitudes blossomed during his February golf vacations in Augusta, Georgia, where he could hop a trolley car or wander the streets without bodyguards. Beginning in 1913, he started spending his winters in southern Florida, at the Ormond Beach Hotel, created by the recently deceased Henry Flagler. He bought a house there in 1918 when he was 79 years old.

The new home, known as The Casements in honor of its awning-covered windows, was gray-shingled and had three stories. Simply furnished and unassuming by Rockefeller standards, the house had 11 guest bedrooms to handle his growing brood of descendants, though it never teemed with as many family members as its owner had hoped.

Rockefeller would grab a walking stick and outline additions to the new place in the wet sand or make quick sketches with a stubby pencil. A veteran sun worshiper, he installed an enclosed porch, which enabled observers to view him, like some American waxwork, sitting inside. Hoping to flood the place with music, he furnished the residence with a Steinway piano, a Victrola, and a lovely church organ. "I reverence a man who composes music," he once exclaimed after listening to the music of Richard Wagner. "It is a marvelous gift."

Now, finally free, Rockefeller for the first time developed true friends, not just golf cronies and acquaintances. His most frequent companion was the ancient Civil War general Adelbert Ames, a ramrod-stiff West Pointer who had been wounded at Bull Run, and who had served as the governor of Mississippi during Reconstruction. On the golf course, Ames was amused by the petty economies practiced by his thrifty friend. Around water holes, Rockefeller insisted that they switch to old golf balls and professed astonishment at players who used new balls in these treacherous places. "They must be very rich!" he told Ames.

Rockefeller, at this time, began to display new sensitivity toward public opinion. In 1914 he and his son retained Ivy Lee, a pioneer in corporate public relations, to help burnish the family's image. Under Lee's tutelage, Rockefeller began to distribute shiny dimes, a custom which endeared him to the public. The world seemed to lighten around the old man. When the 61year-old John Singer Sargent began to paint Rockefeller at Ormond Beach in March 1917, he discarded the stereotypical perspective. Instead of painting him in somber business black, he captured him in one painting in a casually elegant mood, wearing a blue serge jacket with a white vest and slacks. The face was thin but not yet gaunt, the eyes pensive, and the pose softer and more tranquil than in Eastman Johnson's 1895 painting of the tycoon.

With Rockefeller relaxed and serenely confident about his place in history, Junior decided to ease him into a biographical project. In early 1915, William O. Inglis, a genial New York World editor, had been approached to write it. He was sufficiently malleable to toe the line.

During the project, which was never published, Inglis saw Rockefeller's selfmastery crumble only twice, both times when responding to allegations made by Ida Tarbell. The first time came when he read aloud her charge that in 1872 the 32year-old Rockefeller had taken over many Cleveland refineries by threatening rivals. "That is absolutely false!" exclaimed Rockefeller.

"His face was flushed," noted Inglis, "and his eyes were burning. He did not beat the desk with his fist, but stood there with his hands clenched, controlling himself with evident effort."

Rockefeller reserved his most bitter epithets for another passage, where Tarbell dealt with the touchiest matter in his personal life: the character of his colorful, raffish father, William Avery Rockefeller. Tarbell's "character study" was filled with venomous portrayals of the elder Rockefeller, the itinerant peddler of patent medicines who had led a shadowy, vagabond life. William had been the sort of fasttalking huckster who thrived in frontier communities, and Tarbell amply reported his misdemeanors. At one point she wrote, "Indeed he had all the vices save one—he never drank."

The thrust against his dead father probed some buried pain, some still-festering wound inside Rockefeller, and he suddenly erupted: "What a wretched utterance from one calling herself a historian," he declared.

For a moment he could not regain his self-control. His famous granite composure had utterly broken down. And, for one of the few times in his life, he let forth a torrent of intemperate abuse. Sputtering with rage, he railed against the "poison tongue of this poison woman who seeks to poison the public with every endeavor ... to cast suspicion on everything good, bad, or indifferent appertaining to a name which has not been ruined by her shafts." Aware that he had, uncharacteristically, let down his guard, Rockefeller soon checked himself and resumed his old pose of philosophic calm. He reassured Inglis: "After all, though, I am grateful that I do not cherish bitterness even against this 'historian,' but pity."

The titan, upon regaining his dignity, made certain that his tightly fitted mask never slipped again in front of any living soul. He died in 1937.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now