Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

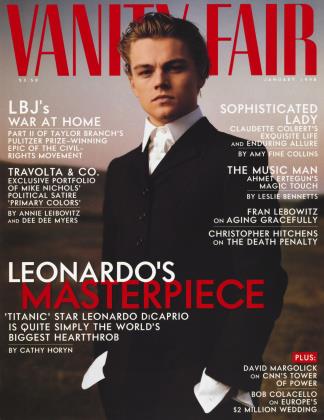

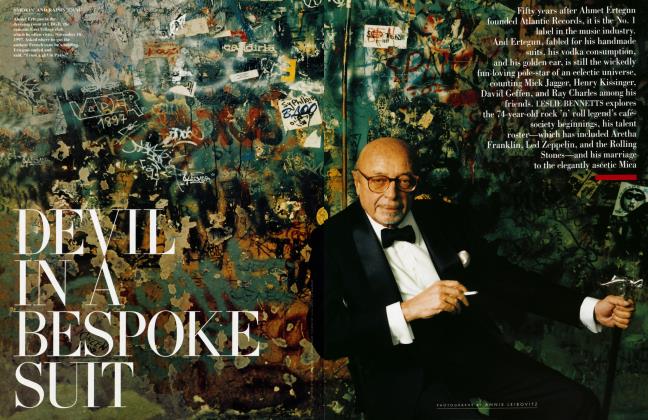

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowFran Lebowitz on Age

In which the famously contrarian humorist explains the difference between growing old and growing up

Most children think being an adult means freedom. Do you think this is true?

A perfect example of a childish thought. There are certain lessons in life that tend to dispel such notions—that are little stepping-stones to adulthood. For me, the first one that I can recall was being about four years old and having my tonsils out. When I was a child, everyone had their tonsils out. The second you coughed, they ripped them right out of your throat. One little rasp, boom, you're in the hospital, your tonsils are gone. It was a common occurrence; it was something that you wanted to do because everyone else did it. It was exciting. I led a fairly dull life as a child, so just the break in routine was something that I didn't really mind. And here's how my parents described it: "You're going to have your tonsils out. You're going to have to go to the hospital, and have an operation, and sleep there overnight by yourself. But it's going to be O.K., because after the operation you can have all the ice cream you want." This was, of course, a stupendous dream. And also my first lesson in adulthood: Yes, you can have all the ice cream you want, but first we're going to slit your throat. If you take that lesson, which I certainly did, you become an unusually bitter four-year-old, or an unusually wise one—how often those two things go hand in hand. And so, my first exposure to adulthood was knowing that at every moment in your life when they're going to let you have all the ice cream you want, you will not be able to swallow it.

Did you ever want to be older so you could stay out late, so you could do whatever you wanted, so you could have sex? No, not to have sex. I didn't want to have sex at four. I seem to be one of the only writers in the country who wasn't having sex at four. But, certainly as a child, I wanted to do the things adults did. The distinction between adults and children was far greater then than it is now. Modern children have hard lives. We were really kept in the dark—away from the world. We didn't have the responsibility of knowing things. Children were expected to be innocent, and it was considered the responsibility of all adults to maintain the innocence of children. For a child to walk into a room where adults were talking in the 1950s was almost invariably to have the adults stop talking. Not only did this spare you the burden of adult knowledge, but it also enticed you by engendering the idea of adult knowingness. In other words, it seemed exciting. It made you want to be an adult. It was forbidden, and so it took on a little of the quality of sex. Therefore, I had quite an innocent childhood, except for what I could manage to overhear, and as I wasn't exactly living with Oscar Wilde and Lord Alfred Douglas, I remained relatively unscathed.

Did you find childhood confining?

Yes, in a certain way. Because we had a lot of rules that children do not have now. We were very strictly brought up. There was no aspect of life for which we did not have a rule.

Parents now burden their children with what is rightfully their own responsibility—that of making decisions. You hear parents ask their children what school they want to go to. What school do they want to go to? Why would a child be capable of making this decision? If you're still of an age when you have to go to school, that would be the hint that you can't choose it.

I do not remember my childhood as being one of questions directed at me. The only thing I can ever remember being asked—and even this only occasionally—was "Which would you rather have, string beans or spinach?" Clearly a seven-year-old wants neither. So I began to have a view of the world where these were your choices. Here are your choices in life: string beans or spinach. Here are not your choices in life: string beans or candy. I think that's a good way to grow up, because the truth is: Here are your choices in life, string beans or spinach.

I hear mothers say, "She has one dress that she wears all the time—I can't get her to wear anything else. " Did you do that when you were a kid?

I didn't. I'm not saying I was a child without desires of my own, but simply that my desires were routinely thwarted. "I can't get my child to do something" is not a phrase I ever heard. What does that mean? They're two feet tall— you're at least three feet taller. You're in charge of them. Our parents knew that. We were scared of them. I don't mean physically—my parents didn't hit us. But they were the boss. We responded to that. We believed in it, and so did they. They spoke with authority. When they said no, it wasn't negotiable. It wasn't a conversation. We didn't have conversations with our parents. I don't mean I didn't talk to my parents; I did. But we didn't discuss what I might do. Even my parents didn't have that many decisions to make, because they had the rules in their heads: This is what you do, this is what you don't do. The whole society had these rules. There wasn't much difference in child rearing from house to house. Some parents were more permissive than others; some were stricter. Some people's parents hit them. Some parents were richer and bought more things for their children, and some parents were poorer and bought fewer things for their children.

But basically a mother was a mother, and all the parents watched you. There were approximately one million mothers. You couldn't do anything. I grew up in a small town. You did something in the street 10 blocks away, the mother standing in that street called your mother. It was like living in East Berlin. If there was one thing I knew, it was that the phones were tapped. I knew that no matter where I was, I was being spied on. Someone was going to tell on me. From a contemporary standpoint I suppose that's considered bad, because children don't develop autonomy, or whatever. And it certainly made me angry as a child, and I certainly found it limiting. On the other hand, it did provide a kind of serenity, as fascism always does. It's like going to Japan: the place is like a giant military camp and it's relaxing to be there. So, probably, if you have to weigh these two things— which you do if you're a parent—I think it's better to go in the direction of fascism. You have a lifetime to make the wrong choices. Don't make them all when you're a child or you won't have anything to look forward to.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 134

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 95

Such as?

I would say, Let's make distinctions. Let's give children something to grow up for. For instance, our parents had adult habits. They smoked cigarettes. They drank martinis. They drank coffee. They ate different food than we did. Children had to have children's food: milk, cookies, apple juice—things like that. Adults had shrimp cocktails, hors d'oeuvres, coffee with lipstick on the cup. Your mother would drink a cup of coffee, there would be lipstick on the cup. That was something: Hey, someday I'm going to grow up . . . What could be more futile than the current goal, which is living forever? Modern parents don't have those bad adult habits, which are now construed to be not merely bad but actually criminal.

When I was a child, I thought only children ate breakfast. Children and men. Even as a child, I knew men were more like children than women were. My father ate breakfast, so I thought men ate breakfast because they had to go to work, they needed a lot of energy. Mothers, all they did was lie around the house, cooking, cleaning, and scrubbing. Mothers didn't eat breakfast, because my particular mother didn't eat breakfast. She had toast and coffee, and cigarettes. That, to me, was what a woman ate, that was a real woman's breakfast. Men and children had orange juice, eggs, and cereal. That's a childish meal. But now most adults don't smoke cigarettes, and I see them drinking apple juice. This seems like such a childish food, almost a baby food. I guess they need the sugar to cheer them up because they're so depressed about not smoking.

Who is responsible for the escalation of youth worship in this country?

The worshipers. The un-youth. And what is most bizarre is that there now seems to be a consensus that there is one desirable age to be, or, more accurately, to look, which is around 23. This is the age to which everyone aspires, or actually I should say perspires. This is shocking not only because it is silly but also because where is the constituency for this? Who does this serve? Where is the segment of the population that will be forever 23? Who thought this up? It can't be the people who actually are 23, since they don't mind getting older, and by older I—and they—mean 24. It can't be the people who are so young that they can't imagine being that old. So it must be the people who are literally old enough to know better—or worse—because they've already passed that age. This makes no sense. You're never going to be 23 again, so why promote this idea? Why cede power not only willingly but stupidly? Why sabotage yourself?

It's like the newspapers and magazines, which are always running charts showing how much money teenagers have, which is always something like 80 zillion dollars of what is always called disposable income. And while it may, in fact, be 80 zillion dollars, the reason it's so disposable is because it is not, in fact, income, at least not theirs. From whence comes this money? From people older than 15. Much older. The money spent by teenagers is largely, vastly given to them by people much older. Why? Why did the people actually in power, i.e., the people holding the cash, give over that power? It's unprecedented. It violates self-interest. Why didn't they instead use that power to say, "Some day, you, too, can look like us, because what comes along with that five pounds you can never lose again and that hair that's never coming back is that platinum credit card, that money in the bank, that undeniable pleasure of having, at long last, all the answers."

Wouldn't this be the better path? The easier, more sensible way? Because this other thing is completely insane. Clearly, the people who thought this up are people who don't have enough to worry about, who don't have enough anxiety, who don't find real life risky enough. Say you've solved all your problems by the time you're 40. Perhaps some people have. I don't know them. Say you've at least solved your financial problems—that happens. Say you've achieved all your goals, even though most people haven't. Now what can you do? What would be really a mountain to climb? Trying to look 23. That's an endless job. That's labor-intensive. That costs a fortune. And, on top of that, it absolutely cannot be done. It doesn't work. There's a challenge for you. Better even than the impossible dream—the impossible nightmare.

W/ZYZ/ else besides vanity do you think fuels this obsession with youth?

Well, first of all, the terror of old age feels to most people like the terror of old age, instead of the terror of death. Both things are operative, but when you live in a society where you don't see death, where the actual physical manifestation of death is rarely in evidence, it makes it easier for us to imagine that we are more concerned with being older than we are with being over.

It makes sense to me that people are terrified of dying. It makes some sense to me that people don't want to get old, but it makes especially good sense in a culture in which all advantage has been given to youth. And "given" is the key word. The superior position held by youth is a matter of perception. So strongly held is this perception that nobody bothers to remark on the fact that it's not true. Here's what is true. It is true that you die. It is true that if you don't die young you get old. And along with age comes infirmity, and you fall apart, and you lose your looks. These things are true. But it still isn't true that all advantage is to youth. There are things old people have that young people don't. Age could be construed as remarkably useful. It should be very valuable. It's absurd that in an era in which there is almost no need for physical vigor it is so highly prized. Almost nothing in this society has to be done by brute strength, by rude health, by physical prowess. In fact, people who use their physical ity for their survival are at the very, very bottom of society. The further you are from using your body for your own survival, the higher your status, unless, of course, you're a professional athlete. Consequently, we all live in this dreamworld where the athlete acts out this fantasy of what is, let's face it, virility. That's not a culture—that's a cult.

Hard physical labor carries so little status and returns so little reward that almost no native of the United States will do it. If you have to earn your living by picking lettuce, chances are you are not even legally in the country. Who really should be going to the gym? Who shouldn't be smoking? Who should be getting eight hours of sleep, a steam, a sauna, a massage? The lettuce pickers. Who needs this stuff? The lettuce pickers. Who doesn't get it? The lettuce pickers. Who instead is lifting weights, stretching muscles, running laps? If you're sitting in a law firm all day, committing white-collar crime, do you really need to drink seven gallons of water? You walk up Madison Avenue, every third person looks like they're on their way up Mount Everest. They have a knapsack, they have a bottle of water. You never know what's going to happen, because you could get to 63rd Street and suddenly there could be a drought. The entire Upper East Side, instantly, it's going to be a desert, a wasteland. Dust blowing through Mortimer's, tumbleweed rolling down the ramp at the Guggenheim.

You see all these people with big muscles, but they don't touch anything, they don't lift anything. Do you need abs of steel to reach into your pocket to tip the guy who takes your suitcase at the airport? Perfect biceps to hail a cab? It's a complete turning upside down of the way the world always worked. It doesn't make sense. What does make sense is a fat Chinese emperor with long fingernails. You want a role model for wealth and power? A real fat Chinese emperor with six-inch fingernails. That tells you right away. This guy weighs 300 pounds, he's not moving. With those fingernails, he's not picking any lettuce.

We live in a fantasy land where we value youth in a totally abstract way. What has value in this culture? Money. Who doesn't have any money? Youth. Did you ever hear anyone say, "I'm going out with this 19-year-old guy. I don't really like him, but boy is he rich"?

What do you think is the general attitude toward teenagers?

Let me begin by saying that I am no fan of teenagers. A more annoying group I cannot imagine. But they are feared and loathed in this country to the point where there are laws against them that are clearly unconstitutional. And, as a great civil libertarian, I am appalled. A curfew? What is this, Poland, 1970? Of course you can't have a law about what time teenagers can walk on the streets. It's unbelievably outrageous that this is tolerated. The fear of teenagers, however, is understandable; they're big, they know nothing, and they have cars. That's a dangerous combo. I think you should be allowed to drive only between the ages of 30 and 40. Before 30 you're too reckless, and after 40 you can't see.

As far as the loathing of teenagers is concerned, certainly it springs from envy of their sexuality, which is most extreme at this time of life, especially for boys. This is primarily why teenagers are dangerous and the reason they are feared. When people say they're afraid of teenagers, they actually mean they're afraid of teenage boys. I know that there are some gangs of teenage girls, but it's pretty rare. I've known many people who've been mugged; I don't think I know anyone who's been mugged by a girl.

Boys are a major problem because now we no longer have use for them. After all, what are they but highly flammable repositories of testosterone? There is no longer a use for this testosterone. We're not going to have any more real wars, and hard labor and the operation of heavy machinery have been largely replaced by soft labor operating light machinery. All the boy responsibility has been shifted either to machines or to people who are very submerged from a status point of view. There's nothing to do with these boys. We can't think of what to do with them, and they can't think of what to do with themselves. So, basically they rape and pillage, which is what they do when they have nothing to do, and thus we not illogically perceive them as dangerous. The reaction to this has been a war on boys masquerading as a war on crime. Boys cause these problems because they're too primitive for the culture. Testosterone is something we needed to start civilization, but as civilization progressed, we didn't need it anymore.

Here are some things that women would not have invented: the wheel, the gun, the internal-combustion engine, fire. These are male inventions, testosteronedriven inventions. In order to get from caves to co-ops, we needed men, or actually boys, because people died so young. Everyone thinks man invented this, man invented that, but really boy did. Boy invented weapons. Boy invented tools. Boy invented all the things we needed to survive before life was a cabaret. So, boy was really good then. But now our culture has passed him by, and what has he become? What do all things become when we no longer need them but still want them? Ornamental. We like their looks, which is why we idolize the male athlete and the male body, which, as it has become more and more marginal to the culture, has become more and more a cult object. The young boy, like the Virgin Mary, is now an object of adoration, but doesn't perform any real function. And what functions he tries to perform, we try to contain. That's why we have all these jails. These jails are filled with boys. They're not filled with men. The only reason that there are men in jail is that we're now so scared of boys that when we put them in jail, we put them in jail forever, where they eventually become men. We don't really need to keep most men in jail, because what they do as boys they're not likely to do as men; they don't have the energy.

It's common, and not wrong, to say that the culture abhors women. The culture does abhor women, but it's petrified of boys. So we punish them for their boyness, but dote on their boyishness. We take 20 of them and make them into giant stars, give them $50 million to be basketball players, football players, baseball players. Now they're big heroes. We love them. We put them in underwear ads. We worship them. Up there, high on the billboard in his underwear, he's beautiful, we adore him. But back down here on the street, we're terrified of him.

Do you think there's a connection between health and vanity?

This obsessive concern with personal health is vanity. Vanity standing in for religion. If you're jogging, people yell, "Good for you." You're admired. You're doing the right thing, like comforting the afflicted or succoring the poor. This shocks me, because it's a purely selfish act. You're doing it to look better and live longer. It used to be that "good for you" meant "good," not "you." People are always saying, in very approving tones, "He works out, he takes care of himself." Taking care of yourself, is that supposed to be our goal? Isn't that a little rudimentary to be the source of admiration? You take care of yourself so that other people don't have to. You take care of yourself so that if called upon you can take care of other people. You take care of yourself so that you have the strength to accomplish something genuinely worthy of adult attention—a quality not readily attributable to 45 minutes on the StairMaster.

There is the belief that if you run, don't smoke, drink apple juice, not only will you live to be 95 or for eternity— whichever comes first—but that what you will be is not actually 95, preceded by all that actually precedes it, but, in fact, 35 for 60 years. Clearly that's the plan. No one really wants to be 95. No one ever sees anyone who's 95. All the people who are 95, we hide. Except for the rare one they trot out to show you how great it can be to be 95. Take all the people who are 95. How many are you going to find that you really want to be, who can still think, who can still walk, who can still even drink apple juice?

So, people want to be not merely forever, but forever and young. And, little by little, they see that they're not. They lead these lives of self-inflicted deprivation, and then one day they look in the mirror and there, where there used to be a very defined line indicating the chin, there is now what can only be described as a kind of smudge. And they—or let's be honest, you—kind of squint and it, let's be honest, kind of disappears. A perfect example of the intelligence of the human body, because surely it is not just random good fortune that at the very moment you are losing that line at your chin you are also losing your ability to see it.

Now, many people respond to this loss of face by racing to the plastic surgeon. To me, this falls into the category of desperate measures. Desperate measures, as opposed to certain measures. A certain measure is one taken at a certain point; for example, the point at which you recognize that although there was indeed an era during which it was possible to stay up for three nights in a row without looking like a particularly ill-used hostage, that era has passed. Certain measures must be taken; you have to go to sleep. A desperate measure is: You pay someone the price of a Jaguar XJ8 to perform major invasive surgery.

I don't care, by the way, if people want to do this. To me, it is not a moral issue. I make moral judgments. This is not one of them. I don't think it's an act of morality or immorality. I just don't think it's warranted. In other words, I don't think that what's happening to your face is that bad.

I see what's happening to my face, and the faces of those around me, and, yes, we definitely used to look better, there's no question, and we're going to look worse, unless we die. And we wish we didn't look this way, because it is less good. This I freely admit. However, do we look so much worse that surgery is called for? I, for one, do not. Now, on the other hand,

I was not the reigning beauty of my day. Plastic surgery, for the average-looking person, is a kind of aesthetic social climbing, a kind of ersatz democracy. Who are the only people who used to have plastic surgery? Rich people and movie stars. Those are the people who should have it. If you were astoundingly beautiful at 25, if you were, say, the young Julie Christie, the normal process of aging is a genuine tragedy not only for you but for all those who looked upon you.

Average-looking people who are perfectly willing—in fact, delighted—to dwell at the very bottom of the moral and intellectual heap hold themselves to a standard of beauty that is psychotically high. I hear people complain about how they look, people I've known for 25 years. To them I say, "What are you complaining about? You never looked that good to begin with. You looked better then than you do now because you were young, not because you were beautiful."

But the truth is that youth isn't everything when it comes to beauty, because, without question, the present-day Iman still looks a million times better than almost every single 20-year-old on the planet. What does aging mean to the average person? That you look better at 20 than you do at 40. What does aging mean to the great beauty? What brain damage would mean to Stephen Hawking.

Do you still have a desire to be current, to keep up?

"Still" is not the word you're looking for.

I never particularly had a desire to keep up, or even, frankly, to sit up. But if what you mean is do I know what's the best club on Tuesday night, the answer is no, I do not. And don't tell me. I want you not to tell me. It's one of those things I don't want to know. I don't want to know my bone density. I don't want to know who called. I don't want to know what's the best club on Tuesday night. When I was 20 I knew, not because I had a desire to be current, but because I was current. That's what 20 means.

What not being 20 means is that half the time I don't even know who these people are. These new movie stars and whatnot. The entire point of a movie star is glamour, and it's impossible for anyone younger than you to be glamorous. Sexy, beautiful, cute, but not glamorous. Glamorous has to be older, beyond your experience, beyond your years. That's what people really mean when they say someone looks like a movie star. Nothing is more telling of someone's age than who they think is glamorous. So, to me, Cary Grant looks like a movie star, Paul Newman looks like a movie star, Warren Beatty looks like a movie star, but Brad Pitt, to be perfectly frank, looks like a trick.

"We live in a culture that values not only youth but also growth and development, and believes that this growth continues throughout life.

Do you think this is true?

No, it is not true. The word "growth" is most accurately used to describe physical growth. To use it in the way that you suggest is an abstraction, not to mention a delusion. A construct grounded in wishful thinking, betraying the basest sort of longing. Physical growth is real. Children start out very short and get taller. They literally grow up. Their feet get bigger. Their arms get longer. Their teeth come out. New teeth come in. I recently had a tooth pulled, and, believe me, I waited in vain. To replace the one tooth that came out, I had to buy three teeth at the cost of a semester at Yale. I am now in a position where I can no longer afford my own teeth. I am living beyond my means simply to chew. So much for lifelong growth. If it doesn't apply to teeth, it doesn't apply.

Endless growth, like endless youth, is not to be found in nature. We live in an era enthralled by nature, obsessed by it, worshipful of it, yet at the same time entirely unwilling to accept its reality. If nature is not reality, then what is? Perhaps it is not really nature that people love. Perhaps it is not really love. Perhaps it is a myth. A canard. A fairy tale. A lie.

You cannot kill an elephant. An elephant. We now value elephants very highly. Because we're not allowed to kill them, we can't use their ivory to make piano keys. We have to keep them, even though, in my opinion, for the elephant it could only be considered a step up to become a piano. You cannot make a piano out of an elephant anymore. To me it is a testament to man's ingenuity and inventiveness that we ever thought to make a piano out of an elephant to begin with. I personally know that if I had looked at an elephant I would not have seen a piano. I am grateful to the person who did. This is what humans are for, to see an elephant and make a piano. We now live in an era where you're not allowed to make a piano out of an elephant. That we ever could, I'm awestruck. That we no longer do, I'm sunk in despair. An elephant should be happy that it can even be a piano. We may not have the perfectibility of man, but we do have the perfectibility of elephant. We can make the elephant into a piano. I personally do not think an elephant would ever have thought to make a piano out of a man.

Do we prohibit the killing of elephants because we love elephants so much? Because we love nature so much? Because we loathe pianos? Or because when it comes to nature we have decided to make certain selections so unnatural that they come close to achieving the condition of art? We love elephants in their natural state, but abhor people in theirs.

People wholly unable to form a single coherent notion seem to have no trouble at all entertaining diametrically opposed points of view. Save the whales, get rid of the gray. Old-growth forests, new-growth hair. Organic tomatoes, silicone breasts.

Perhaps it is not really the elephant's life span that concerns us. Perhaps we have decided that it is easier to deal with the elephant's mortality than it is to deal with our own. It is, after all, easy enough not to kill an elephant. You simply have to not kill an elephant. What could be simpler? What could be more humane? What could be a greater tribute to our empathy, our compassion? All of which we have for elephants, none of which we have for ourselves. Gray, wrinkled, hardly lithe, the elephant is a thing of beauty— the first wife, a thing of the past.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now