Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLA BOHÈME

An unconventional woman with a searing talent, Berenice Abbott documented a changing 1930s New York in 125 photographs on view this month

Photography

She surveyed the city with a cartographer's eye. Her lean, muscular images document the shifting silhouette of New York pushing out of the 19th century and into the 20th—the rising skyscraper,

the steel span of a bridge, the hardware store whose stock spills out onto the sidewalk. "To photograph New York City means to seek to catch in the sensitive and delicate photographic emulsion the spirit of the metropolis, while remaining true to its essential fact, its hurrying tempo, its congested streets, the past jostling the present," wrote Berenice Abbott in a 1935 grant proposal to the Federal Art Project. And what had already been six years' work became Official Project No. 265-6900-826: the more than 300 photographs known as "Changing New York." In March, an exhibition featuring 125 images from the series opens at the Museum of the City of

New York, celebrating both Abbott's centennial year and the museum's 75th anniversary, and the complete project has been reproduced in the recently published Berenice Abbott: Changing New York (New Press).

Abbott left Springfield, Ohio, for the Bohemia of Greenwich Village in 1918, rooming with Djuna Barnes. In 1921 she bought a oneway ticket to Paris, where she took a position as Man Ray's darkroom assistant (she qualified for the job because he wanted to hire someone who knew nothing about photography); she's also credited with having taught him how to dance. It was in Paris that she began taking the blazingly iconographic photographs that are the defining images of the writers and artists of her day—James Joyce, Jean Cocteau, Sylvia Beach. Abbott's 1928 portrait of James Joyce simply is James Joyce. Her 1927 photograph of Eugene Atget is the only known portrait of the French photographer, and Abbott is almost singlehandedly responsible for bringing Atget's work to public attention.

"A master-artist who is an inventor, too ... a woman who is as practical as Ben Franklin," wrote poet Muriel Rukeyser of Abbott. Abbott's infrequently seen science photographs of the 1950s are stunning images of the unobservable, illustrating science as it had never been seen before—wave forms, magnetism, the transformation of energy. She invented and patented the Abbott Distorter and other photography-related technology through her own company, the House of Photography. In addition she wrote several successful how-to books, and in 1935 founded the photography program at New York's New School for Social Research, where she taught for 23 years.

"The tempo of the metropolis is not of eternity, or even time, but of the vanishing instant," she once wrote. A pioneer, a visual historian, a woman passionate about capturing the truth of her subject, unadorned—Berenice Abbott has given us the past, and in it we find our future.

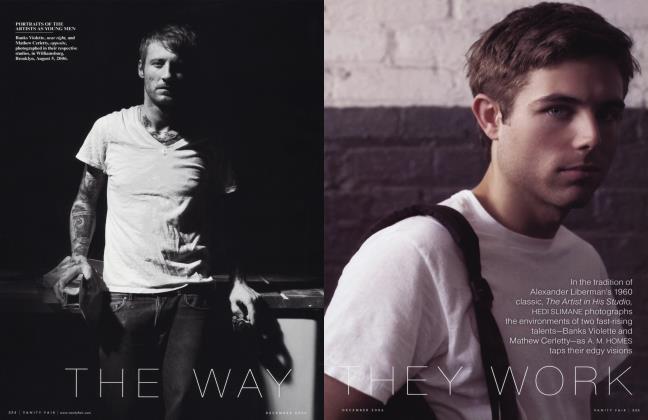

A.M.HOMES

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now