Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

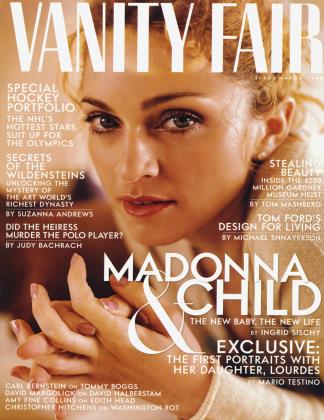

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE FORD THAT DRIVES GUCCI

Business

With the looks of a matinee idol, the determination of a Panzer commander, and the pop-culture antennae of a teenager, Tom Ford has turned a tired Italian leather-goods firm into a $1 billion international fashion force. Right now, Gucci is cooler than cool

MICHAEL SHNAYERSON

Tom Ford wants you in black. Gucci black. Though if you must have a little pink jacket and skirt, he might compromise here and there. As long as what you wear from head to toe, sunglasses to shoes, is Gucci. Worldwide domination, country to country, is what Ford's after. And when Tom Ford sets his mind to a plan, he tends to get what he wants.

Ford is in black himself as he slides into a banquette at New York's Cafe Luxembourg for lunch: a black largecollared shirt, black tapered pants, black square-toed shoes, black denim jacket. "Full Gucc," as the latest slang has it. He has the strong-jawed looks of a matinee idol, as all-American as his name, which CONTINUED ON PAGE 141 CONTINUED FROM PAGE 136 HI a bUSineSS

of image and beauty hasn't hurt. For a designer, he's also unusually well spoken and focused. But these aren't the only ways Ford has distinguished himself from the pack.

In just three years, Ford has transformed a moribund Italian leather-goods company into the hottest name in international fashion. His forays into hardedged glamour have produced clothes that seem as supercilious as they are sexy: metallic-black jackets and hip-hugging pants, patent-leather-strap evening dresses with gold G logos, micro-minis, and killer stiletto heels that dazzle fashion editors at the shows and fly off the racks at Gucci's more than 150 stores around the world. Miuccia Prada, Helmut Lang, Jean Paul Gaultier, and Jil Sander, among others, have also produced clothes that are edgy and hot, but nobody in fashion can report a turnaround story as spectacular as Gucci's: from $250 million in gross annual sales amid the specter of bankruptcy to its current status as the envy of the industry, with sales of $1 billion. In achieving this, Gucci has done more than set fashion trends. Its brilliant success in going public has inspired many of its rivals to do the same. And the sight of a young American shaking the dust from a vener-

"To gay men Tom's a dream. Straight men admire him. Then, with women, forget it."

able European house has caused an almost madcap scramble for other Americans or Brits to revamp other European companies. Under L.V.M.H. Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton's wide umbrella alone, the Americans are Marc Jacobs at Vuitton, Michael Kors at Celine, and Narciso Rodriguez at Loewe; among the Brits are Alexander McQueen at Givenchy, and John Galliano at Christian Dior. Not every American product, however, is a Ford.

Asa breed, designers publicly shudder at the mention of commerce, and tend to rely on a business partner for running the company. Gucci has 54year-old Domenico De Sole as its shrewd C.E.O., but Ford has immersed himself in the business as well. A selfprofessed control freak, he's closely involved in the designs for all of Gucci's 11 merchandise lines, from handbags to home decor, some 5,000 products in all. He plans the ad campaigns, redecorates older stores, and designs new ones down to the shade of paint for the walls. "He has a real sense of what modern marketing is about," says Suzy Menkes of the International Herald Tribune, the reigning doyenne of fashion critics. "He understands that image is as much about how you handle the media, what you have in the windows, and what your videos are as about the clothes." Like Warhol, who was an early influence, Ford has a cunning grasp of pop culture and how to use it; at the center of the fashion world, he's also an outsider looking in, musing on what a designer is and can be.

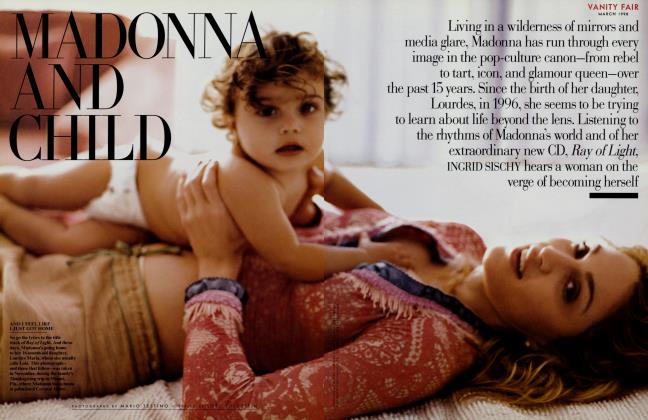

Along the way, Ford has become an icon himself. Lionized at fashion shows, he's now a hit in Hollywood, where Madonna, Uma Thurman, Gwyneth Paltrow, Goldie Hawn, Toni Braxton, and Rita Wilson, among others, have discovered that the designer is as cool as his clothes. Last summer, Wilson, the actress and wife of Tom Hanks, was among those who helped Ford pull together a glittering evening that raised $1.2 million for AIDS Project Los Angeles with a Gucci fashion show, dinner, and dancing for more than a thousand; Ford, a onetime actor in television commercials, got a standing ovation from the star-studded crowd. "He's like the sexiest gay man alive," Wilson exclaims.

"If he were a movie star he could be openly gay because you'd still want to see him kissing women. He's that sexy."

"I don't know anyone who is actually so many different things positively to different people," says Lisa Eisner, a Hollywood socialite and fashion muse who has become a close friend. "To gay men he's a dream. Straight men admire him as a businessman. Then, with women, forget it. There are hardly any women who don't wish he was straight, because he's so charming. He has an inherent natural glamour, an old-fashioned, movie-star thing.

"Also," she says, "he smells good all the time."

In his role as Gucci's global overseer, Ford travels constantly. "I've never met a man on a jet more often," says Women's Wear Daily's editorial director, Patrick McCarthy. Ford's week leading up to our lunch, he reports dutifully, began in L.A., where Gucci is building a new store from the ground up on Rodeo Drive, and where Ford just bought a Richard Neutra house in Bel Air. He flew back to Paris, where he does much of his designing, and where he keeps an apartment with his companion, journalist Richard Buckley, European editor at Conde Nast's House & Garden. He flew to Florence, where Gucci is now based, then to Milan, where much of its business is still done. He flew to London, where a new Gucci store on Sloane Street was nearing completion, and where he and Buckley have another house. Then back to Paris one night for dinner. Then to L.A. again, and now to New York.

But Ford looks chipper, and ready for his role that evening as a presenter and nominee at the VH 1 fashion awards. For the first awards ceremony, three years ago, says John Sykes, president of VH 1, it was hard to get Seventh Avenue to support the idea of putting fashion into a new arena. "Tom was one of the first to appreciate the power of television for fashion. He pulled me aside at the first one and said, 'No matter what the critics say, after tonight, keep this going—it's going to change the fashion business forever.'"

After winning three VH1 awards in two years, Ford knows his chances are

nil this time. No matter: beaming the images of Gucci clothes and their suave creator to four million viewers is what counts. Yet the prospect of not winning has at least symbolic import. Having expended his 15 minutes of triumph as fashion's newest darling, Ford knows he and Gucci have to get on to the next stage of less brilliant but more sustained growth, from conjuring up the shoe or handbag of the season to building a full wardrobe brand.

In Milan last October, Ford's spring 1998 women's collection began the transition. "I felt I had pushed Gucci as far in one direction as I could," he explains. "I couldn't have made the skirts any higher,

I couldn't have made the heels any higher-people would have fallen over! But also it wouldn't have been Gucci anymore. In one sense I had to take the company that far in that direction to kill the old Gucci image. It really had to become fashion." The message this time, he says, was: Slow down. "People come to us wanting the next hype, the next trend. I think we gave it to them, but the changes were subtler." It was, in a sense, selfpreservation: not even a prodigy like Ford can reinvent fashion twice a year.

The reaction was largely favorable, but mixed. "I loved it," says Vogue's Anna Wintour. "He's refining what he does, becoming more confident. It's getting stronger now because he's added everything you need: color, decoration ..." "What he brought to the table this time was a softer Tom," says Harper's Bazaar's Liz Tilberis. "It was still very focused, but a lot of silk jerseys. And that shock of pink in the middle of Tom's dark colors! Pink shantung coat, very stiff, battened fabric, and pink skirt. You could hear the gasps from editors who all instantly wanted it in their pages." But Suzy Menkes, an often tough critic of Ford's in the past, found the last collection "a mishmash," and adds, "There was a coat with a sequined lining that was really glam. The rest was rather vulgar. But

"I pushed Gucci as far as I could le the skirts any higher," says Ford

I'm sure when you see it in the [advertising] campaigns it will look great."

At the fashion awards Ford is proved right: no VH1 honors. Narciso Rodriguez, the former Calvin Klein protege who made Carolyn Bessette Kennedy's wedding dress, is the new face this year. Fashion, so animated and defined by change, wants to move on. Somehow, even as Ford dials back Gucci from radical to restrained, he has to stay in front. "In the next six months," he says, "I have to find what's new."

Six weeks later, I wend my way through the narrow streets of the Sixth Arrondissement to an 18th-century building overlooking the Seine. Two floors up, Ford ushers me into a high-ceilinged apartment so devoid of color I feel I'm entering a three-dimensional photographic negative. Yapping at knee level is a terrier named John, undressed at the moment but often gussied up in outrageous drag for Polaroids that get sent to his owners' close friends.

"I have this problem with color," Ford says, with a wave at the rooms within. "Partly it's that I don't want to think about what to wear when I get up. It's like whatever your job is, you don't want to deal with more of it on your own time."

About as far as he's ventured is beige. The sofas in the living room, based on a Jean-Michel Frank design but sketched for production by Ford, are beige. So are the French travertine end tables. A German Arts and Crafts table by the window, with Mies van der Rohe chairs, follows the scheme; so do the 1920s French lamps. "The only color in the room," Ford says, "is the pink of this book here." He's referring to a book on architect Luis Barragan that lies under several others on a beigeand-black sideboard. A thin book, its pink spine showing. "If you're visually obsessive," he says, "everything has to be balanced. I just wanted one little touch of color." He shrugs off my quizzical look. "You can't describe why. It's not objective."

Ford likes to declare that he wears only black. Disbelieving, I make him

"My worth dropped about 50 percent" when Gucci's stock fell last fall, says Ford.

show me the closet in his bedroom. Sure enough, every one of the suits and jackets is black. He opens a deep drawer below to reveal stacks of new black Gucci shirts—although he does wear the occasional white one. There's no white underwear, though. "I don't wear underwear," Ford says. "It's one extra layer; you look thinner without it."

Because Ford is a man who's in a different city every day, a lot has happened since our lunch. A new ad campaign, for one thing. Mario Testino, the photographer who set the standard for Gucci's early ad campaigns under Ford, has been succeeded by Luis Sanchis, though Testino's blithe, chic perversity will likely be maintained—since it's Ford who comes up with the ideas, chooses the models and hair and makeup people, looks through the viewfinder, and inspects the Polaroids. The image is key. "That's what goes out to the world. That's the final design."

The oil-slick gray paint of the study we're sitting in is the shade Ford chose for the Gucci store that just opened in London. The scent he's wearing is Gucci's new Envy for men. Then there's his watch: at Ford's urging, Gucci has just bought the Swiss licensee it's used for 25 years. Though the new G watches advertised everywhere are his design, Ford didn't feel he had enough control over the product. The acquisition will add $190 million to Gucci's annual sales. And with the watch company comes its $18 million ad budget, which gets added to the $65 million Gucci will spend advertising its other goods. "It's crucial in terms of what the customer sees," Ford says happily. "Gucci, Gucci, Gucci."

But what of the New Thing? Ford says he's onto it, enough to have designed the fall 1998 men's collection and half of the women's line as well. Yet so far, by early December, its shape seems defined more by what it's not than by what it is. "We've been living off this retro period in fashion for the last three or four years," he observes. "Not only in fashion but architecture, music, movies ..." Ford himself has been tagged a "retro" designer because so many of his clothes play off the last three decades: the 60s-style plastic go-go boots, the 70sstyle velvet hipster jeans, the 80s-style

padded-shoulder jackets. As a devotee of 70s style, he was without doubt the right man at the right place and time. A decade before, Karl Lagerfeld had seized on the Reagan-era return to tradition to reinvigorate Chanel. Ford was smart enough to see that Gucci's more ostentatious past—"part Riviera, part Hollywood kitsch," as he says—might perfectly suit the cynicism of the 90s. Cynicism, he likes to point out, is one of the main ingredients of fashion. "Someone who says, 'I know this is really awful, but I'm so cool I'm going to wear it anyway.'" Retro mocked the past, yet embraced it, with a fin de siecle irony that found perfect expression in Ford's revival of the Gucci logo, so gaudily displayed it came full circle to elegant.

"My career has been built on retro fashion because I've tried to do what every fashion designer tries to do, which is kind of feel what's in the air and turn it into a tangible product," Ford says. "But I can feel the retro thing is too mass now. Boogie Nights, The Ice Storm. Every bubble-gum commercial, they're sitting in Eames chairs and drinking out of 70s-style glasses."

What Ford has to do, he knows, is react faster to that than everyone else. "Everyone else will be sick of it, too," he says. "They may just have not figured it out yet because they don't scan as many magazines as I do. And by the time they're sick of it, the new thing has to be waiting there for them. And when they see it, they'll go, 'Wow, I didn't know that's what I wanted, but doesn't that look good to me!' "

Taking these cultural soundings is what fascinates Ford about design. He's not the sort of designer who, as he puts it, does a new line based on his life-changing trip to Bali. And while a couturier like John Galliano can supply the exquisite confections stars, models, and photographers need for fashion shoots, Ford designs for the racks; the discipline of the marketplace appeals to him. The trick is to follow his own instincts. "I read a story about [Vuitton's] Marc Jacobs not long ago," he says, "and one thing I noticed was that he seemed to be asking Vuitton, 'What should I do?' 'What should this be?' Which to me seemed the total wrong approach: tell them what they need!"

At the same time, sea changes do oc-

cur, and a designer can't be left on the beach. Ford likes to muse on the gradual shift from white to black over the last two decades: from white clothes, carpeting, televisions, and cars in the 70s to black everything in the 80s and 90s. It's a reaction, he's convinced, to the coming of AIDS and a general grimness in urban life. The timing, for a man who eschews color, has been apt. The next sea change appears to be toward a new romanticism, a reaction against not only black but also the strung-out look that goes with it. At Harper's Bazaar, Tilberis's new operating byword is "S.E.S.": models should look sexy and elegant, and be smiling. Frills and lace are in. Softness is in. Color is in. Is Ford out?

"Frilly and lacy is totally wrong to me," Ford says with some irritation, "and the reason is I don't find it modern. You still have to walk down the street—today's streets. You have to feel safe, secure, confident. Our times are a little too tough for lacy, in my opinion." Instead he's headed, a bit cautiously, toward a new classic look.

"The pendulum of fashion swings," he muses. "Sometimes fashion is fashion. And sometimes nonfashion, very classic, is fashion." For the men's show, Ford's gone to two-button, classic blue blazers— "But not just classic, different classic!"— and shoes with rounder toes. Though he doesn't say it in so many words, he's clearly aiming at Giorgio Armani, hoping his own tightly tapered suits—the antithesis of Armani's loosely draped look—can be, for the next generation of men, the uniform that Armani's has been for the past 20 years. For women too, the look will be more classic, but with three more months to finish the next collection, Ford is less clear, or perhaps just more secretive, about how that will be expressed: the search, at any rate, goes on. That it will end in brilliance, assure fashion's leading arbiters, is not in doubt.

er Interview editor Bob Colacello. "But we liked snobs."

"A designer like Tom or Helmut Lang or Marc Jacobs will freshen up their look or give it a new silhouette," says Wintour. "But they're not suddenly going to put huge ornamentation on their clothes. We'll see more ornamentation on a shoe, but Tom can do that within his own style. In fact, the most important shoe of the fall collections was his." "You don't want to see him do John Galliano," adds Tilberis. "He moves forward enough for us to appreciate the changes. That's the greatness of a really good designer: he's out there on his own, and then we assimilate it."

Meanwhile, involved as he is with Gucci's global business, Ford has spent a lot of time these last six weeks worrying about Asia. Nearly half of the company's revenues come from Asian customers, particularly the Japanese, who prize luxury leather goods even more highly than do Westerners and until recently flew in droves to Hong Kong and Hawaii to buy them on the cheap at duty-free shops. Last September, Gucci's Domenico De Sole became the first luxury-goods C.E.O. to warn of a slowdown in Far East business—despite, in Gucci's case, a 29 percent increase in sales by midyear. For its candor, Gucci was rewarded with a 50 percent drop in share price over the next two months.

For both Ford and De Sole, the drop had rather dramatic personal consequences. Their worth in company stock isn't large enough to require public disclosure, but analysts figure each was worth about $80 million on paper last spring and only about $40 million now. "My worth dropped about 50 percent, yes," Ford says evenly, "but I'm not going to tell you what the numbers are. But that's all right. It's paper. And I have a long-term commitment."

The larger implication is that with its stock so low, and its profits still relatively high, Gucci is a takeover target. "Anyone who's got two and a half billion can have it," observes Edouard de Boisgelin of Merrill Lynch. "It's a public company; there's not much they can do." De Sole did try instituting a poison pill of sorts: by his provision, large shareholders would be hard-pressed to exercise clout. De Sole says it was meant to protect small shareholders from being railroaded. Clearly it was also meant to keep the company in current hands. The provision failed. "Some of the biggest shareholders voted against it," De Sole says glumly.

Certainly, one keen observer of these proceedings was L.V.M.H., the French U conglomerate headed by one of fashion's most artful businessmen, Bernard Arnault, which owns Christian Dior and Givenchy, among others. As Gucci's biggest rival, L.V.M.H. is rumored to be circling, which has fostered another rumor: that Gucci is trying to find an American white knight to buy 30 percent of the company. De Sole denies this. And Ford waves off the threat of L.V.M.H. and its aggressive chairman. "Why would a man whose main business is so dependent on the Asian market buy a company that has depended to a large extent on the Asian market at a moment when predictions for the Asian market over the next 25 years are not great?"

To deal with that forecast themselves, Ford and De Sole are working to prop up the brand in cities where it has languished. "If you look at the business Giorgio Armani does in Houston or Dallas or Chicago, we haven't begun to go after that," Ford says. "It means stealing away store managers and buyers who have regular wealthy customers, and better service, and new tailors—all of that." If, despite those measures, a takeover comes, Ford is philosophical. "It's a very interesting time," he concedes. "But, you know, I've been through other interesting times at Gucci. I was there when the company was practically bankrupt and we didn't have photocopy paper and all my assistants had been fired. That was interesting."

Ford was, in fact, a virtually unknown designer in 1990 when he went to work for Gucci in Milan. Dawn Mello, president of Bergdorf Goodman, had just moved over to be Gucci's creative director, and hired Ford, then at Perry Ellis America in New York, to design an expanded line of women's ready-to-wear.

© CD CO © CD E color/' Ford says with a wave at the rooms within his Paris apartment.

He arrived in Milan at the denouement of a very bad Italian soap opera.

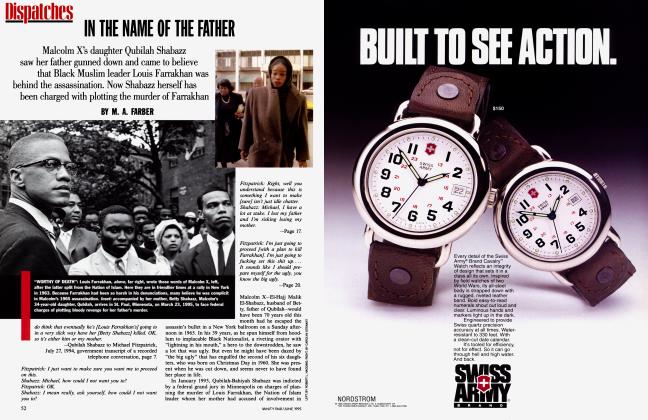

Through the 80s, the Gucci clan had I had notorious fallings-out. Some 15 I lawsuits had been filed by relatives against one another. Rudolfo Gucci had died, leaving his 50 percent of the company to his son, Maurizio—a bequest, muttered detractors, made possible by the efforts of Maurizio's lawyer, Domenico De Sole. Then Rudolfo's brother, Aldo, patriarch of his generation, went to jail for tax evasion on evidence supplied to the court by his son

Paolo. Aldo, who had parceled out 10 percent of his own half of the company to his three sons, had to endure the further indignity of seeing Paolo sell his 3.3 percent share to Maurizio, which gave Maurizio control of the company. Declares one former Gucci associate, "It's a business built on blood."

During the infighting, family members had milked the brand by making myriad licensing agreements—some 22,000 in all—that produced mediocre goods. Maurizio slashed licensed products and sales outlets alike, intent on restoring Gucci to its former glory. Cash flow dried up, however, and the company went into a tailspin. This was a shock to Investcorp, the Bahrain-based company that had bought half of Gucci in 1988 for $160 million with the hope of taking it public in four or five years for a killing. It also made life extremely difficult for Mello and Ford.

"We couldn't pay designers," Mello recalls. "So they all left, and Tom became the sole designer for all 11 product lines. There were days when he never slept." Ford wasn't always sure he'd be paid, either. But the experience was terrific. Early on he designed a clog that outsold Gucci's traditional loafers; a trendsetting stiletto heel did even better and is still, in various permutations, among Gucci's biggest sellers. But while Ford was relatively free to design shoes and accessories as he wished, Mello had strong ideas about what Gucci's ready-to-wear should be. ^ Along with Maurizio, she wanted a clasi sic look. Only when Mello reclaimed g her old job at Bergdorf's in mid-1994 was 2 Ford able to create his own Gucci style.

By then, Investcorp had bought out Maurizio's remaining interest for some $170 million, and installed De Sole as C.E.O. (Maurizio would be shot to death on a Milan street in 1995, apparently for failing to pay back a personal loan from the wrong people.) "I was the only designer on the team who was left," Ford explains. "Domenico was the businessman who was left. The two of us were thrown together. And Investcorp was sorting out the company. The last thing they were even thinking about was the design. So I had this open window to do whatever I wanted!

"Given his eye and the way his sensibiity works," says CAA's Bryan Lourd, "there's no reason he won't be a film director."

I could send anything down the runway; no one else would object."

At first, the two survivors made for wary partners, each advised by gossips not to trust the other. Lines had to be drawn: when De Sole tried to sit in on a handbag-design meeting, Ford threw him out, and a furious argument ensued in the factory parking lot. De Sole backed off, "He had no choice," Ford says. De Sole acknowledges he was nervous. "We were under real pressure." Investcorp was said to have given up trying to take Gucci public, and to be shopping the company for a pittance to L.V.M.H. If Ford and De Sole hoped to stay in charge, they had to act fast.

Yet Ford's first collection as design head, in October 1994, was a bust. "Very 1950s," recalls The New York Times's Amy Spindler. "Teapot prints, dirndl skirts ..." Ford realized he was holding himself back, still hindered by Mello's classic perspective. Fortunately, he and De Sole had come to trust each other; De Sole had given Ford his freedom, and the designer had shown he was a shrewd businessman, making the most of a then skimpy advertising budget. The design breakthrough came in January 1995, with a men's collection of stunning, futuristic glamour, highlighted by patent-leather coats and pants with an almost metallic finish soon seen in knockoffs everywhere. These, as Spindler observes, were clothes for jet-setters, not stay-at-home socialites. There, and in the March 1995 women's fall collection that followed, Ford showed a tightly focused range, ruthlessly edited to emphasize one new shoe, one new accessory, one new day and one new evening look. After years of sitting through overlong collections with a hodgepodge of outfits, the fashion world found his clarity, and his cool, exhilarating. "By the next season," says Spindler, "everyone knew."

Among the most delighted parties was Investcorp, which staged its initial public offering after all, issuing stock for half the company in October 1995, the rest a few months later. As Gucci's worldwide sales doubled, then doubled again, other designers staged I.P.O.'s of their own, among them Donna Karan, Ralph Lauren, and Mossimo. Fashion houses realized that their business had

gone global, both in design and distribution, and they'd better go with it.

With half a dozen successful collections to his credit now, Ford at 36 has become the Gucci man he envisioned when he did his breakaway collections: a rich and famous jet-setter. He should be thrilled. He isn't. "Live by the buzz, die by the buzz saw," he says dryly. "The higher you go and the more the whole thing is buzzed and yakked, the more you just know they're going to rip you down."

On the few nights each month they're together in Paris, Ford and Buckley often go for dinner to a small, charming restaurant called Marie & Fils on the nearby Rue Mazarine. Inexpensive, quiet, and good, it's also distinguished by a leggy waitress in slinky black pants that bear the alluring label Pussy Pants. "Wish I'd thought of that," Ford says as we settle in at a table by the window.

In his own designs, Ford gives allure a hard edge: the woman clad in Gucci has done it all, knows what she wants and whom she wants to do it with, and lets nothing stand in her way. It's an image of femininity, as Ford observes, that a lot of men and women find exciting, and one that reflects his belief that sexual roles are more changeable, more fluid, as he puts it, than society's labels suggest. Proclaiming oneself gay is just one of those labels, he says, which indeed in his case is especially confining since for his first 18 years he thought he was straight.

In Santa Fe, where he spent his teenage years after a Texas childhood, Ford dated girls, and handsome as he was, he had no shortage of choices. Perhaps his love of fashion should have clued him in; as his friend illustrator Ian Falconer says, "He dressed too well to be straight." Ford's two poles of taste were his mother, who looked, as he says, exactly like the actress Tippi Hedren— blond hair worn up, clothes very tailored, simple high heels—and his paternal grandmother, Ruth, a flamboyant, fashionobsessed Auntie Marne character who wore "big hats, big hair, big fake eyelashes, and big jewelry—bracelets, squashblossom buckles, concha belts, and papier-mache earrings." When his grand-

mother put her house on the market a few years back, he paid a sentimental visit. "It smelled the same way, it looked and felt the same way. I'd lost my virginity right there on the floor ..." So he bought it.

"Though his family wasn't wealthy— both parents were real-estate broI kers—Ford wore Gucci loafers from the age of 13 ("People used to tease me about Gucci"), attended tony Santa Fe Prep, and went east to college, at N.Y.U. Lonely at first, he jumped at a classmate's invitation to go to a party and then to Studio 54. "I had no idea there was an ulterior motive," Ford recalls. The party was hosted by a young man-about-town named James Curley; when he and Ford's new friend Ian Falconer greeted each other, they kissed. "We went into this party, and all of a sudden I realized that everyone there was a guy. And they were all kissing each other, which seemed stranger still. And then someone said, 'Oh, Andy's coming by any minute.'" Warhol did arrive, and the group sailed off to Studio 54, where Warhol asked the handsome new boy earnest questions, and drugs appeared out of nowhere. "It was a bit of a shock," Ford says. "He couldn't have been too shocked," says Falconer, "because by the end of the night we were necking in the cab."

Soon Ford was going out to Studio 54 every night, sleeping most of the day, and attending virtually no classes. "It was exactly what you wanted if you were a kid from Texas and New Mexico and had come to New York. It changed my perception of everything. I've fed off that period a lot in my work." Warhol especially intrigued him. "I'm not sure he wasn't a bit evil. But he was so smart." Vanity Fair contributing editor Bob Colacello, then editor of Warhol's Interview magazine, remembers Ford as "one of those preppy kids who hung around the Factory on an occasional basis. He was very good-looking. He had longish but neat dark hair, sort of swept over his forehead; he had a great smile, which he still does, a toothpaste-ad smile, and he was always in a

he one who knew people," says Ford's boyfriend, Richard Buckley.

blue blazer and blue oxford-cloth shirt, Levi's 501s, and Bass Weejuns or Brooks Brothers cordovan loafers. He was a sweet kid, with an all-American freshness, and a bit of a snob. But that was all right. We liked snobs."

With his good looks, Ford began acting in television commercials—at one point he had 12 running concurrently—and dropped out of N.Y.U. at the end of his freshman year. "Everything I loved about my life had nothing to do with school," he says. Eventually he went to Parsons school in Manhattan for environmental design. One night close to graduation, he concluded that he would make a good fashion designer. "It was a very calculated decision," he says. "I could speak well, didn't look bad, liked fashion—I had all the necessary tools! And once I figured it out, then it was just a matter of how to make it happen."

Ford put together a book of sketches and told prospective employers he'd just graduated from Parsons, neglecting to add that his degree was in architecture, not fashion. He met a lot of rejection, but wasn't bothered at all. "I guess I'm very naive, or very confident, or both. When I want something, I'm going to get it! I was going to be a fashion designer, and one of these people was going to hire me, and that was that." Finally he found a vulnerable target in designer Cathy Hardwick. "He called me every day," Hardwick recalls. "Then every week, every two or three days. I told him on the phone that I had no position open. But he was very polite. 'Could I just show you my book?' Finally I gave in one day. 'How soon can you come up?' 'One minute,' he said. He was down in the lobby."

Ford became Hardwick's assistant, making $32,000 a year. He did anything she needed. One day, she sent him to

help get her apartment ready to be photographed by The New York Times. The apartment had been done by Mario Buatta, who was there and in a tizzy making last-minute adjustments. "He looked stunned at the way I was moving around," Buatta recalls. "Decorators get sort of frantic when the Times is coming, at least I do. And he was from the leisurely world of fashion. So I kept whirling around, and suddenly I realized he'd vanished. 'Where is that Tom guy?' I bellowed. I found him hiding in the bed-

room! And then I really got mad. I said,

'I would never have someone the likes of you as an assistant.'" "And I," Ford said, "would never work for the likes of you!"

A side from Hardwick, who had become a close friend, nearly everyone in Ford's life now was male, and gay. He'd confided in his father, but his mother seemed not to want to know, and his parents were getting divorced, "so I thought, Why throw it in her face? The day my mother asked me was the day I told her." Ford was 29. The issue of coming out still rankles him, though. "Maybe it's because I'm one of the lucky people who's always felt comfortable with myself, [but] if someone asked me to describe myself in 10 words, 'gay' wouldn't even be one of the 10 words. ... I would like it

if one day our species would transcend all this, so that you'd say, 'Oh, are you going out with John?' And I'd say, 'I was going out with John, but we broke up; now I'm dating Lisa.'"

Sexuality is fluid, he's convinced. "You move in and out. I feel more toward the heterosexual side of the scale at this stage in my life than I did 10 years ago. And, honestly, if I weren't in a relationship with Richard now, which I am, and very committed to, there are women I'm very attracted to, who I would hate to think wouldn't consider me as a boyfriend because I was 'gay.'"

It was Hardwick who introduced Ford, whom she calls "Tender Tom" to distinguish him from an older Tom in her family, to Buckley, then an editor at WWD. Buckley had noticed Ford at a fashion show, and asked Hardwick about him. Ford does a dead-on imitation of Hardwick's Korean accent: "Ah, Tendah! Reechahd Buckley from the Women's Wear Daily likes you! You have dinner with him, deah, he'll put lots of pictures of our clothes in the WWD\" Eleven years later, Hardwick likes to remind Ford that in the Korean culture a matchmaker whose match lasts more than a decade is entitled to a huge present from the happy couple. "'Tendah!' she'll say. 'Where's my car?'"

Early on, however, the relationship

"If I weren't in a relationship with Richard now," says Ford, 'there are women I'm attracted to. I'd hate to think they wouldn't consider me as a boyfriend because I was 'gay.'

seemed doomed: Buckley developed tonsillitis, which turned out to be cancer. When a surgeon announced that Buckley had a 35 percent chance of living five more years, Ford began calling influential New Yorkers on Buckley's WWD Rolodex out of the blue. One was Blaine Trump. "He said, 'Richard would be very upset if he knew I was calling you, but he's in trouble; can you help?' " Trump, who was on the administrative board of Memorial Sloan-Kettering, used her clout to get him in right away. "It was hard for him to call a stranger," Trump says of Ford, "but that's the person Tom is." Months

of painful radiation followed, during which Buckley doggedly came to work every day in a new job—as an editor at Vanity Fair. When it appeared the treatments had killed the last of his cancer, he and Ford decided the stress of New York might have been an unhealthy environment. Ford, then working at Perry

Ellis America, persuaded Mello to hire him at Gucci. Mello called Mirabella's founder, Grace Mirabel la, who hired Buckley as her new magazine's European correspondent. The two men started work in Milan the same day.

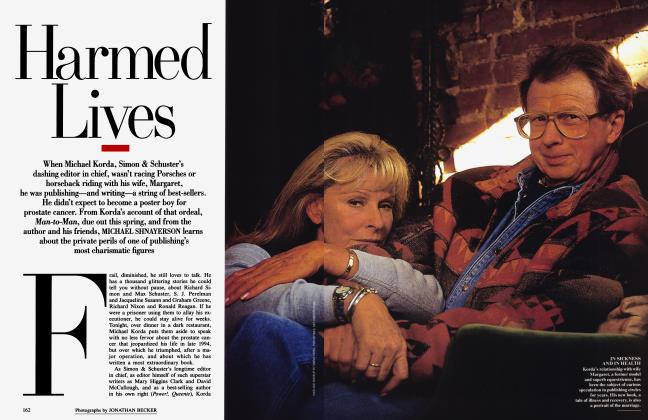

Nine years later, at 49, Buckley is healthy and fit, a lean, austere figure with silvery hair, ice-blue eyes, and chiseled features. Over coffee at a big, brightly lit hotel near the Paris apartment, I ask him the obvious question: next to cancer, can there be anything harder on a relationship than the sudden, brilliant success of a younger partner?

Buckley laughs wryly. "It's like A Star Is Born, isn't it? 'I am Mrs. Norman Maine!' It's true that I was the one who knew people, and when we went places in New York, people would always ask Tom, 'Now, what's your name again?' Flash forward to Vanity Fair's Oscar party two years ago. There was

some Hollywood decorator there; we kept bumping into him, and he kept introducing people to Tom, and he'd turn to me and say, 'Now, what's your name again?'" Buckley shrugs. "I don't know. . . . There have been moments where I've had to remind him I'm not his assistant or his secretary, but that doesn't happen very often. If we were both designers, and I was a star, and then suddenly I was designing for Kmart and he's suddenly Tom Ford of Gucci, that might bother me. But I'm a journalist. I have a certain tenure in the business. . . . The only thing that's really hard is that he travels so much.

We don't have the home life we used to have."

That may change as the two consolidate their lives in London. Along with setting up a main residence, Ford is moving his design studio there, which may make for less jet-setting. On the other hand, he's pondering a prospect that would mean even more travel: a new career as a film director. Far from being threatened, Buckley takes an older partner's pride in the prospect. "I don't doubt that if he wants to do that he will," Buckley says. "Because he's talking about it now the way he talked 11 years ago about wanting to be a designer."

I am very interested in film," Ford confirms, "because it has a longer life span than fashion. Fashion is literally about a moment—the moment that someone walks into a room wearing an outfit that makes everyone gasp. Even later that night when she takes off her dress, it's gone. But you can see the dress worn by an actress in a movie and have it be alive again when you play the video. And if you're a control freak, film direction is the ultimate: a whole world that you design."

Bryan Lourd, the CAA agent, ac-

knowledges having had a number of talks with Ford about Hollywood prospects. He doesn't represent Ford—yet— and, as he observes, the man has a fulltime job. "But in my mind, given his eye and the way his sensibility works," says Lourd, "there's no reason he won't be a director. If you're a fashion designer, you can go into film; that's the time we're living in." Exhibit A: A Time to Kill director Joel Schumacher, who started as a window designer at Bendel's. "But also, this guy specifically is so much a product of the film-and-television culture that I think he was more designed to do that, in a weird way, than to do what he's doing now. I'm certainly not encouraging him to leave what he's done—it's too much fun to see what comes out of that sick, twisted mind, but I think that he can travel if he wants to."

For the near term, Ford says, he'll stay at Gucci. "It's not finished for me. It's not done."

But to get to film or anything else, Ford needs to stay hot. He needs the next collection to work as well as all the others. He needs the next new thing.

Just after New Year's, I check in to see how it's going. His women's collec-

tion for fall 1998—the collection that bows this month in Milan—is nearly done. What's the new thing?

"I'm using a lot more color," he allows. "And things will be a lot less perfectly matched. There'll be more variation. Beyond that, I really don't know— and if I did, I wouldn't tell you!" In fact, 50 percent of the women's collection for fall 1998 is done and in the stores. But that's the lesser half. The rest are the clothes Ford still has to design before this month, from which will come the clothes for the runway, the clothes that define the next look. Ideas are turning in his head, but a lot will be left to eleventh-hour creative chaos. In these frantic days before the show, he'll be ripping out shoulder pads, changing shirt shapes and lengths, changing the tailoring—changing the whole thing. To yet a newer thing. "Whatever it is, it will be concise," he vows. "You'll see it over and over on the runway. So if it's publicized before, it won't have the impact it needs to have. The moment the light hits the first model, everyone has to be seeing it for the first time." And judging. Is it new? Is it right? Will it play? Will it sell?

This month, the verdicts come in. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now