Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowTHE BALLAD OF ROUTE 66

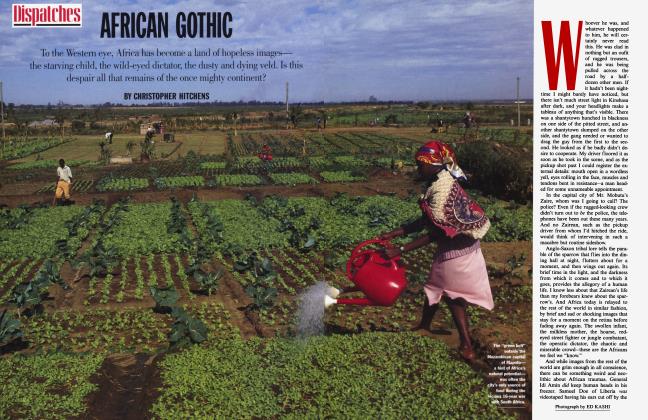

CHRISTOPHER HITCHENS

Route 66, the highway immortalized by Nat "King" Cole, once spanned the landscape of John Steinbeck and Scott Joplin, of Woody Guthrie and Jack Kerouac. From Chicago to L.A., the author searches for a world that is vanishing as fast as the taillights of his blazing-red Corvette

Joseph Heller's masterpiece, originally entitled Catch18, was renamed—or should that be renumbered?— by its editor, Robert Gottlieb. Comes the question. Would the novel have had the same pervading influence under its first digits? I can think of at least some reasons to doubt it. First, certain numbers have hieroglyphic power, and repetition has something to do with this quality. Just take the figure six. Consider the mark of the beast and its three sixes. Then, not every number can be made to rhyme with "kicks." Get your jive on Route 55? Not really. Get to heaven on Route 77? Feel free on Route 33? Too insipid. No hint of sexty-sex ...

Whereas when Bobby Troup's wife leaned over and whispered in his ear as they were speeding toward California in the heady days of postwar liberty in 1946, murmuring, "Get your kicks on Route 66," he knew at once that he had a song right there. (Bob Dylan had to do "Highway 61" twice, or "revisit" it, and still didn't get the same effect.) Sixty-six is three times Heller's 22. Two sixes is a good throw at dice, and always gets a cheer—"Clickety-click, all the sixes, 66"— at bingo. Nat "King" Cole took the song off Bobby Troup's hands at once, and he sang the refrain as "Route Six Six" with no damage to the lyric. Since then it's been rerecorded or reworked by Dr. Feelgood, Buddy Greco, Depeche Mode, Chuck Berry, Bing Crosby and the Andrews Sisters, Rosemary Clooney, and the Sharks. Mythology says that Jack Kerouac heard the song on a jukebox in 1947 and decided on the spot to take a westward road trip. I first heard it in the great year of '66 itself, when it was belted out by the Rolling Stones. Here are the words, which have become the song lines of America's western destiny:

If you ever plan to motor west, travel my way, Take the highway that is best Get your kicks on Route 66! It winds from Chicago to LA, More than two thousand miles all the way. Get your kicks on Route 66! Now you go through St Looey, Joplin, Missouri And Oklahoma City is mighty pretty, You'll see Amarillo, Gallup, New Mexico, Flagstaff, Arizona. Don't forget Winona, Kingman, Barstow, San Bernardino. Won't you get hip to this timely tip: When you make that California trip, Get your kicks on Route 66!

When I first bounced to Mick Jagger doing this, I initially heard the fifth line to say, "Forty-two thousand miles all the way," and thought, Jesus, the United States is big. And when I lowered myself behind the wheel of a blazingred Corvette in Chicago in August and pointed myself at the Pacific, the country ahead didn't seem too small, either. From Grant Park on the shore of Lake Michigan—scene of riots at the 1968 Democratic convention—over to the junction of Santa Monica and Ocean.

Just to answer any questions you might have before I roar away: much local politics is highway politics. After the passage of the Federal Highway Act in 1921, which mandated interstate roads, it was determined that east-west highways would have even numerals, and northsouth highways would have odd ones. Roads that cut state lines would be designated by shields, intrastate roads with circular signs. Major highways would carry numbers ending in zero. The Chicago-Los Angeles one was to be called Route 60. Or so the Illinois and Missouri authorities decided. But 60 meant so much to the state officials of Kentucky and Virginia that they were prepared to fight over it. The number 66 was still free when the Illinois, Missouri, and now Oklahoma bureaucrats caved in. So the famous "66" shield was born, and in 1926 marked 800 miles of paved road. It took until 1937 to pave the remaining 1,648 miles of gravel, dirt, and asphalt. In 1977 the route was decommissioned and replaced with a new interstate, which, as if in numerical mimicry of the year '77 and the number 66, leaves Chicago as Interstate 55, becoming 44 in Missouri before evolving into a banal 40 and an indifferent 15 before hitting L.A, where it peters out in Interstate 10 to the Pacific.

Yet the attachment to the music and mythology of the old road was and is very great, and for long and short and very broken-up stretches you can still leave the main "drag" of interstate-land, with its homogenized gas stations and chain restaurants and franchise motels, and take a spin into a time warp or a parallel universe, where you might have swerved suddenly into The Last Picture Show or Bonnie and Clyde, or even The Twilight Zone. It's all going, and going fast, but then, in my Corvette, so could I.

Perhaps, here, a word about the car. There was a TV series in the early 1960s called Route 66, where a couple of lads played by George Maharis and Martin Milner acted as knights of the road on a generic highway, backed by a theme tune from Nelson Riddle and employing a Corvette as a talisman and prop. The ladies among you will not (I hope and trust) be familiar with the sensation of strapping on a huge and empurpled projectile protuberance at about the midsection. But any man who has sat in the driver's seat of a fieryred Corvette and seen the sweeping and rising hood twanging away in front of him may, as he looks along the barrel, want to make a wild surmise. The song by the artist who was then known as Prince, "Little Red Corvette," just doesn't cover it. Stephen King's mad-car-disease novel, Christine, is based on the huge number of songs from the 50s and 60s that personalized automobiles by giving them names, invariably female. My Corvette was too slim and graceful to be a boy, but it wasn't exactly a chick either. I soon got bored with forcing Winnebagos and U-Hauls to dine on my dust, and began to humble ever faster machines, including that of an Illinois state trooper who was fortunately engaged with someone else. The shimmer of Lake Shore Drive and the grime of A1 Capone's Cicero fell away behind, and I was even thinking irresponsibly of giving downstate Illinois a miss until conscience pricked me to visit Springfield, home and resting-place of Abraham Lincoln.

At once I fell victim to three of the many banes that afflict the modem road warrior in America. Towns that have multiple exits don't tell you which exit will take you to, say, where you want to go. There is never anybody on the sidewalk to ask. People in cars, if you can catch them as every red light suddenly goes green, usually aren't from here. And when you do find a local, he or she doesn't know the way. It was a Hooters bar that finally helped me to get a fix on Honest Abe; the waitress knew several of the key sites and scrawled them daintily on a napkin and gave me a terrific quesadilla into the bargain. Thus I discovered, following the old brown "66" shields through a shaded part of downtown, that Lincoln may have been reared in a log cabin but it wasn't in Springfield. I also came to the painful realization that was to recur to me times without number. A shiny red Corvette can be a boy magnet, all right. When parked, it drew to my side many garage mechanics and hotel doormen and learned young black men and polite old roadside coots who would inquire after the finer points and details. When in motion it would summon cops from deserted streets and vacant landscapes. But it appeared to leave the female sex quite unmoved. Could it be a fault in the design? Perhaps the silhouette? I began to brood, and in fine brooding country.

Nat "King" Cole sang the refrain as "Route Six Six" with no damage to the lyric

Southem Illinois is flat. There is the punctuation of grain silos and elevators (and the elevators now have their own museum, just like every other "66" feature and artifact). This is "the prairie state" and signs along the road announce the restoration of prairie grass, to forestall complaints about unmown roadsides. Some of the 66 byways are explorable, but they are flat, also, and their surfaces are often too rugged for a low-to-the-ground beauty such as I am driving. Then, to the right, there's a sudden sign for the MOTHER JONES MEMORIAL, and I swing to it on impulse as the sky makes a long and leisurely turn from robin's-egg blue to glaring red. Here, just outside the little town of Mount Olive, is the incongruous sight of a cemetery devoted entirely to the union martyrs of the coal industry. And Mary "Mother" Jones, queen of the labor hellraisers, has her shrine in its precincts. She was born on May 1, 1830, before there even was a May Day, and lived to be a hundred. This region, now so rural in appearance, was once a heartland of King Coal and the proving ground for the great John L. Lewis and his United Mine Workers. The rows—better say the ranks and files—of tombstones almost all bear German and Hungarian and Croatian names, and the dates of half-forgotten massacres on bloody picket lines. It was the coming of the highways that helped break the railroad monopolies in this and other states: another way in which the open road is associated with liberation. I bowed my head at the gate, where it said, THE RESTING PLACE FOR GOOD UNION PEOPLE, and was given a honk and a wave and many high signs by a carload of (entirely) boys as I drove away. Perhaps not many Corvettes are seen making this particular stop. At this stage, I reflected irrelevantly, I was about seven hours from Tulsa.

Mythology says that Jack Kerouac heard "Route 66" on a jukebox in 1947 and decided on the spot to take a westward road trip.

I crossed the big Mississippi into St. Louis—forever to be mispronounced as a result of Bobby Troup's lyric—as the darkness thickened and the lights picked out the huge arch, gateway to the West, that when finished in 1965 presumably did not make every tourist think consciously or unconsciously of McDonald's and wonder where the twin arch had gone. St. Louis is the city of Charles Lindbergh, pioneer of the aviation industry, which was to supplant both rail and road. It used to be the hub of Trans World Airlines, now deceased, and the TWA symbol was being replaced with the logo of a brokerage on the stadium where the Rams play. ("Flying across the desert on a TWA," as Buddy Holly sang in "Brown-Eyed Handsome Man," "saw a woman walking 'cross the sand." Who will get that line a decade from now?) This is an odd combination of frontier town and respectable town: the birthplace of T. S. Eliot and of Martha Gellhorn, the first of whom fled it because it was too provincial and uncouth and the second because it was too straitlaced. In the heart of music history it occupies a soft spot, as the birthplace of Chuck Berry, the home of the Scott Joplin museum, and the home, if not the native one, of Miles Davis and Tina Turner.

The most striking thing to me, however, was the constant reminder of Middle America's German past. It's not just the prevalence of the Anheuser-Busch and Budweiser ambience. There was a big Strassenfest, or street fair, in progress, and in Memorial Park were playing the Dingolfingen Stadtmusikanten Brass Band, Die Spitzbaum, and the Waterloo German Band. Some 58 million Americans tell the census that they are of German origin, even more than say English, and you would never really notice this, perhaps the most effective assimilation in history, any more than you "notice" that the minority leader in the House and the majority leader in the Senate are named Gephardt and Daschle.

In the morning, on an open-air platform of the St. Louis transit system, I fall into conversation with another visitor, named Kevin Honey wood. He wears a nice hat and works for IBM, and he is also looking for a decent place to eat down by the river, so we hunt as a pair. Mr. Honeywood is a boyhood veteran of black South Side Chicago, and as the Big Muddy runs past our equally long and meandering lunch he tells me many things about the old days of "66" as it ran through his neighborhood, things I could never have learned from driving through it. People knew which stretches they weren't allowed to use along Cicero and Cermak and McCormick, but on July 4 they liked to block a section of Ogden Avenue for drag racing. Driving is much easier now for black folks; the rhythm of the road starts to hit me more and more as a variation of upbeat and downbeat, as well as a rapid fluctuation of American geography and history.

In the evening I pay a call on Blueberry Hill, a bar out in the city's "Loop," where Chuck Berry still stops in to play one Wednesday each month. There's a Hollywood-style "walk of fame" on the adjoining sidewalk, with stars and short canned biographies for Tina Turner and the others. The joint itself is a bit tame—ID cards mandatory at the door and that sort of thing—but it has a terrific jukebox and girls playing darts in daring couples and an Elvis Room for events. There's no way to check out the urban-legend rumor that Chuck Berry once had also this ladies' room wired for video. I'm beginning to weary of hamburgers already, but the signature version here is highly toothsome and comes with a cheese peculiar to St. Louis which I failed to write down but mean to check out. Still, the evening needs a round-off and so I favor BB's Jazz, Blues, and Soups, nearer the river, with a drop-by. A convincing rainbowcoalition band with a very strong sax is doing its stuff, and the tourist hour seems to have safely passed, until a terrifying skullfaced blonde detaches herself from a gaggle and whacks me in the features with a star wand. "How ya doin'?" I always think, What kind of a question is that?, and I always reply, "A bit early to tell." She gives me another smack with the wand and holds it up so I can see the number "50" emblazoned at the center. "It's mah birthday!" Christ. Does she know about the Corvette?

The next morning I roared past the Mississippi, scattering lesser cars like chickens, and nod to the Gateway Arch while noticing for the first time that gateway is an anagram of "getaway." Then it's down through Missouri and toward the Ozarks. Long ago, when there was an Ozark Airlines, I noticed at airports that that name was "krazo" spelled backassward. The hillbillies have taken enough sneers in their time, and you can tell they don't care, because the landscape is cliched with revival chapels of obscure denominations, gun shops and gun shows, and liquor stores that say "whisky" or "whiskey" and mean bourbon. This is John Ashcroft country, or was until he lost the Senate race to a deceased person. On the radio, people who are very obviously products of evolution quarrel at the top of their leathery lungs with the verdict. My radio can't shake them for miles, but eventually finds a station that plays Chuck Berry singing the first of his songs that I remember—"No Particular Place to Go." This man's music, remember, is on the twin Voyager space probes, in case there is intelligent life anywhere else.

There are shimmering lakes and grand old steel and iron bridges on the side roads, and the wooded hills make it easy to amble, but I'm sorry I did because by the time I got to Springfield, Missouri, at evening the whole place was shut. It was a Sunday, and most restaurants just don't bother. I finally ran down a steak house, where the automatic raunchiness of the barmaids and waitresses, as they lobbed backchat with the guys, was some consolation for the surrounding Sabbath gloom. Only some consolation, though, because it put me in mind of John Steinbeck's line in The Grapes of Wrath about "the smart listless language of the roadsides." Reduced to the TV in my motel, I lucked into a rerun of Thelma & Louise, which, while it may not be the best buddy and road movie in history, surely features the best blue jeans. Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis pick up Brad Pitt on the way to Oklahoma City, which I was hoping to hit myself by the next nightfall. Among the soundtrack songs are "Badlands" and "Ballad of Lucy Jordan," which showcases Marianne Faithfull's 19th nervous comeback and tells of a girl who never had a ride in a car like mine.

One of the many breezy names for Route 66 is "the mother road."

The name Joplin seems to necessitate a stop, like the Bobby Troup line says, and on the way there's a good side stretch of the old Route. On its two-lane pavement, the mirages seem shinier and deeper, and there isn't the eternal nuisance of great swatches of black tire tread, or tire shed, flapping like crows or writhing like snakes under your wheels. For miles I saw no cars in either direction. The town of Albatross was to all outward appearances fast asleep. In Avilla, almost nothing broke the stillness. I tried Bemie's Route 66 bar, with its shanty look and old Pabst Blue Ribbon symbol, but a rail-thin man wearing only jeans and a cowboy hat (and guarding a sign on the fridge that read, FREE BEER TOMORROW) told me they didn't open until late. Following a road of unattended lawn and garage sales, I came to the comparative metropolis of Carthage, where in a slumberous old square there is a marker claiming the town as the site of the first major land battle of the Civil War. On July 5, 1861, it seems, local gallantry fought off "federal dominance" of Missouri in a series of what the polished granite calls "running engagments" (sic). That was enough to muse upon until I hit Joplin, which is a wilderness of strip malls and traffic stoplights. "Anything to see or do round here?," I asked the young man in the music store, determined as I was to purchase some independence from the radio stations. "Jack," he replied briefly, knowing from my credit card that this was not my name. Sad to think so of a town that has the same name as Scott and indeed Janis.

There are about a dozen miles of Kansas on Route 66, and if you blink, then, well, you aren't in Kansas anymore. A few of those burgs where, when the wind drops, all the chickens fall over. Kansas City, home of those "hungry little women," is back in Missouri. Best floor it and get to Oklahoma. In Missouri, a distinctive feature is the pull-over pay phone that has been downsized to allow you to call while sitting in your car. In Oklahoma, the keynote is roadside exhortation. Not only is Oklahoma ready to proclaim itself "Native America," but it is also "Cherokee Nation." Regular signs instruct you to KEEP OUR LAND GRAND. It's the boostering and the upbeat that force the downbeat into mind, and not just because of the luckless Cherokee and their "trail of tears."

One of the many breezy names for Route 66 is "the mother road," but this phrase was first deployed by Steinbeck (whose centennial is this year) in the following tremendous passage from The Grapes of Wrath:

Highway 66 is the main migrant road. 66— the long concrete path across the country, waving gently up and down on the map, from Mississippi to Bakersfield—over the red lands and the gray lands, twisting up into the mountains, crossing the Divide and down into the bright and terrible desert, and across the desert to the mountains again, and into the rich California valleys.

Sixty-six is the path of a people in flight, refugees from dust and shrinking land, from the thunder of tractors and shrinking ownership, from the desert's slow northward invasion, from the twisting winds that howl up out of Texas, from the floods that bring no richness to the land and steal what little richness is there. From all of these the people are in flight, and they come into 66 from the tributary side roads, from the wagon tracks and the rutted country roads. Sixty-six is the mother road, the road of flight. [My italics.]

The title of his 1939 classic—and just try imagining that novel under a different name—comes from the nation's best-loved Civil War anthem. (It was Steinbeck's wife Carol who came up with the refulgent idea.) When first published it carried both the verses of Julia Ward Howe and the sheet music on the endpapers in order to fend off accusations of unpatriotic Marxism. But really it succeeded because it contrived to pick up the strain of what Wordsworth called "the still, sad music of humanity." Another subversive, Woody Guthrie, effectively set the novel to music with Dust Bowl Ballads: combine these with the photographs of Dorothea Lange and you have a historic triptych. A song of Guthrie's—"The Will Rogers Highway," another folksy name for 66— manages to rhyme Los Angeles with both "Cherokees" and "refugees." (Guthrie sounds a bit folksy, too, when you replay him today. But without Woody, never forget, we would have no Bob Dylan and perhaps no Bruce Springsteen.) I remind myself again that this superficially cheery and touristic route was a road of heartbreak for hundreds of thousands of the poor white underclass, who were despised foreigners in their own country.

But black Oklahoma was visited by tribulation far worse and somewhat earlier. (You can revisit part of it in Toni Morrison's Oklahoma novel, Paradise, which is the perfect antidote to Rodgers and Hammerstein.) In Tulsa, I made a stop to see the Greenwood memorial, which ought to be better known than it is. The Greenwood quarter of town included in 1921 a thriving business district, known as "the Negro Wall Street." On June 1, 1921, it was torched from end to end in a vicious and jealous pogrom, which burned out most of 35 city blocks, incinerating more than 1,200 homes and businesses as well as at least a half-dozen churches. The forces of law and order either pitched in or stood aside while as many as 300 citizens were murdered (and planned exhumations may raise that figure). Planes from neighboring airstrips reportedly even dropped explosives into the conflagration. As a symptom of bad conscience, part of the front page of the Tulsa Tribune and part of the editorial page were later ripped from the files, and it took a long while before acknowledgment was made, let alone reparations.

The name Joplin seems to necessitate a stop, and on the way there's a good side stretch of the old Route.

It's not an easy part of town to find, and I felt awkward asking directions, but a white receptionist in a motel near the Broken Arrow exit went out of her way to give me slightly too much guidance (and a clip from the local press about the monument), and when I got lost again I was told "follow me and I'll take you there" by a white female motorist. The neighborhood is still surrounded by vacant lots, and somebody has smashed one panel of the memorial, but as I pulled away, Tulsa's nearby Art Deco district seemed friendlier, and I even managed a bleak smile at the signposts to Oral Roberts University, former employer of Anita Hill.

Oklahoma City, miles on through more red-soil country, is not so pretty. (Oh, the sacrifices that songwriters will make for a rhyme.) And some of its inhabitants are a tad bored by its piety. In the joint that I find as evening descends, the bony young barman tells me that locals head for Texas for three things (it's always three things): "Booze, porn, and tattoos." His plump gay colleague, when I ask if there is anything else to look forward to on the road, exhales histrionically and breathes the magic name "California ..." The thin one is an ex-soldier who gives directions by reference to army and air-force bases, and I notice again how much Route 66 has evolved according to military imperatives. It was pulled out of the Depression by the huge traffic of armaments and trainees between the coasts after 1941 —Oklahoma! itself was the big musical Broadway hit of the wartime years—then hymned after 1945 by ex-G.I.'s spreading their wings, and finally doomed by President Eisenhower, whose Cold War push for an interstate system had been influenced by the imposing straights and curves of the German autobahns.

A resentful ex-soldier, indeed, was the prompting for my pilgrimage the following morning. On the ruins of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City is another shrine to the murder of Americans by Americans. A reflecting pool borders a garden with the same number of upright symbols as there were victims of Timothy McVeigh. From a distance these symbols could be anything, but on close inspection they prove to be statuary chairs: rows and rows of stone-and-bronze chairs with straight backs to represent the bureaucratic pursuits of the innocent dead. There are 168 of them; 19 are slightly offputtingly half-size to mark the murder of the children at the day-care center and elsewhere.

The figures 9.01 and 9.03, which confusingly could be dates, are incised in stone to indicate the unforgiving minute that it took for the huge building to slide chaotically into the street. A new whitish concrete statue of Jesus stands with its back to the scene. It's all slightly bland, and the inscription puts the blame on generic "violence" rather than native American Fascism. When this memorial was unveiled, the United States wasn't yet a country that honored the frontline nature of office work. It's clearly a style of commemoration in which we are fated to improve, as the upward curve steepens.

Caring little for booze, porn, or tattoos, I noticed as I dressed to leave Oklahoma City that my white socks, washed together with my red ones, had produced a furtive but somehow flagrant pink. Secure in my own masculinity, and bodyguarded by the sleek Corvette, I decided to make nothing of it and turned the proud prow of the car toward Texas, the resulting unit one potent and seamless weld of man and machine. I stopped on 66 at the town of Clinton, which has the best of the "66" museums, featuring an antique T-Bird and an overloaded Okie truck, and paid a call on the Tradewinds Motor Hotel, now a Best Western, where Elvis Presley used to stop over and sleep on his way to and from Las Vegas. Room 215 is the one his manager always reserved, and the lady at reception, responsive to the name of Vanity Fair as well as to my own charisma ("Seen ya on that Fox tee-vee"), gave me and my pink socks a key. The same love seat is still there, with added photographs but—I thought—a bathroom too small for the King's heartbreaking needs. He never showed his face in the daytime, but was once spotted by a roomservice maid who went on a Paul Revere ride to alert the whole town. After that, he signed a few autographs, checked out, and, according to at least some accounts, has never been seen in this area again.

To rejoin the main drag, one takes old 66 through Erick, a dying dump which used to be home to Roger Miller. I tipped my hat to the singer of "King of the Road," which I consider the best bum-and-hobo ditty since "Big Rock Candy Mountain," and passed on. As I thundered past Elk City, I was listening to Elton John— who, oddly, seemed to be imploring someone, "Don't let your son go down on me"—when I heard and felt an impressive whomp somewhere in the rear. The thoroughbred car seemed to shake it off with abandon until, a mile or so later, it nearly threw me by wrenching the steering wheel from my grasp and lurching like a stallion on amyl nitrite. Managing to gain the roadside, I was informed by the screen on the dashboard that the left rear tire had blown and I had experienced "reduced handling." The Corvette has tires which can drive flat for a while, so I limped on, man and machine a single, soggy weld of sagging flesh and soft rubber. Finding a turnoff, I entered the other, parallel world of those who live by vehicular misfortune. Larry's Transmission Shop was mercifully near the exit, and there I whimpered in, with the car (which is able to get in touch with its feminine side) looking suddenly like a brilliantly colored but wounded bird. Larry and Charolett Posey succored me, let me use their phone and their front parlor, refused all money, and summoned another Larry. Indeed, they activated a network—a whole underground railroad—of Larrys. A guy came swiftly with his truck, looked at the tire, briefly pronounced, "She's history," and gave me a ride, with the round and ruined object, back into Elk City. Here, at Larry Belcher's truck and tire center, I was allowed to hang out while strong men frowned at the rare catch. There were no 18-inch tires to be had anywhere in Elk City, and the Larrys built me a patch which they wouldn't guarantee would last as far as Amarillo, 140 miles over the horizon. It was, one of the men said, the worst puncture he had seen since he left his army unit in Korea 12 years ago. The damn hole looked as if it had been made by a bullet. (His National Guard unit was being recalled to the colors, and he wasn't that thrilled about it.) It was perhaps at this point, in a world of gruff and tough men who do nothing all day but wrestle with grease and machinery, that it occurred to me that my pink socks were a mistake. Arguably a big mistake. I think I may have sounded unconvincing and even a bit fluting as I bid farewell and decided not to miss my one chance of saying "Is This the Way to Amarillo?" Tony Christie's simpering 70s hit (he dared to rhyme "pillow" with "willow" while crooning and weeping) plainly hadn't registered with my rescuers, and so I drove on with a fragile tire: man and machine now an uneasy meld of psychological and mechanical anxiety.

However, I had promised myself to risk the byway that reaches the ghost town of Texola, and there was still enough daylight to chance it like a real man. In this part of southwestern Oklahoma, past the rock cuts and bridge spans of the undulant Ozarks, the horizons recede to the utmost, and the red soil shows itself only when there are roadworks. The land flattens out toward the Texas Panhandle, and there Texola lies, desolate down a deserted track. Its position right at the border has meant that it's also been named Texokla and Texoma in its day, before a prewar vote settled the matter. But the 100th meridian has been surveyed seven times, so that the locals had at various periods lived in both Texas and Oklahoma without knowing it, or at any rate without having to move, or care. The point is moot now, because Texola is dead, its barns and shacks boarded up and occasionally adorned with a NO TRESPASSING sign. This is one of the stretches where 66 is still made up of the original white portlandcement concrete squares, which are quaint enough but too quaint for a bulging and patched tire, let alone a bulging and patched driver. I tooled slowly back to the modern world and whispered softly to the Corvette all the way to Amarillo, which with Larry's fine work we reached without incident. On the way, outside the town of Groom, was advertised the largest cross in North America, forcing itself on everybody for miles around, but I deliberately stopped whispering at that point in case anyone thought I was beseeching not just one inanimate object but two.

You can still leave the main "drag" and take a spin into a time warp or parallel universe.

Why a town should be named "Yellow" I don't know, unless it's after the famous rose of Texas or some long-demolished adobe, but the tones of Amarillo are identical to those of any other town. At this point the society and the landscape begin to vary a bit: you see more horses than cattle—and some noble palominos at that—and begin to hear Spanish on the streets and on the radio, and I was asked to check my unlicensed gun at the door of a restaurant. (I wasn't packing one, so I disobeyed.) But Texas still wasn't as different as it likes to think. You hear a lot about the standardization of America, the sameness and the drabness of the brand names and the roadside clutter, but you have to be exposed to thousands of miles of it to see how obliterating the process really is. The food! The coffee! The newspapers! The radio! These would all disgrace a mediocre one-party state, or a much less prosperous country. Even if you carry Jane and Michael Stern's Roodfood guide, you can't always time your stops to it, and if you can't, why, you are at the mercy of the plastic industry and its tasteless junk. The coffee is a mystery as well as an insult: how can it be at once so bitter and so weak? (In "Talking Dust Bowl Blues," Woody Guthrie sings of a stew so thin that you could read a magazine through it; today's percolators contain the ditchwater equivalent. It tastes as if it were sucked up through a thin and soured tube from a central underground lake of stagnant bile.) And talking of reading, what can one say about the local press? It looks like indifferently recycled agency copy from the day before yesterday, relentlessly trivial and illiterate. Happening upon a stray copy of USA Today seems like finding Proust in your nightstand drawer instead of a Gideons Bible. And as for the radio—it was a dismal day when the Federal Communications Commission parceled out the airwaves to a rat pack of indistinguishable cheapskates, whose "product" is disseminated with only the tiniest regional variations.

I hear the first curtain-raising show about the 25th anniversary of Elvis's death as I enter Amarillo, and something in me causes me to lift the phone and send some flowers to my rescuers, Larry and Charolett, back in Elk City. A posy for Ms. Posey. I make it anonymous, except for "the guy in the Corvette." No doubt this will resolve any remaining doubt in her mind about having aided a limp-wristed Brit, but so much the better for the next straggler on that road.

This is John Ashcroft country, or was until he lost the Senate race to a deceased person.

The great Dr. Samuel Johnson had his answer ready when he was asked whether it was worth visiting some piece of scenery. "Worth seeing," he replied, "but not worth going to see." One has to make this snap decision often along Route 66. The Meramec Caverns, supposedly a hideout of Jesse James's and perhaps the site where the first bumper sticker was handed out? No. The Cadillac Ranch outside Amarillo? Yes, all right. In the dirt on the western edge of town 10 Caddies, ranging in model from a 1948 Club Coupe to a 1963 Sedan DeVille, have been driven into the ground at what local freaks say is the same angle as the Great Pyramid of Cheops. First rammed home in 1974 by Stanley Marsh, the cars were moved away from the city in 1997 as the sprawl increased, and are now right next to a handy snake farm.

As I trudge across the field toward the half-buried vehicles I am treading where Bruce Springsteen once trod. He later wrote "Cadillac Ranch":

James Dean in that Mercury '49 Junior Johnson running through the woods of Caroline Even Burt Reynolds in that black Trans Am All gonna meet down on the Cadillac Ranch.

Sounds improbable. Spray paint—the very essence of Pop art—had been layered thickly over the exhibits, giving them the look of New York subway cars in preGiuliani days. Nobody had written a single thing of interest. I was at first their only visitor, but as I traipsed back across the field I met a man wearing a CHICAGO LAW ENFORCEMENT jacket who said brightly, "Definitely not something you see every day!" No, sir, but if I did see it every day I'd very soon stop noticing it. Nothing goes out of date faster than the ultra-modernistic. Exiting, I see a sign that reads: BATES MOTEL. SHOWERS IN ALL ROOMS. TAXIDERMY. KNIVES SHARPENED. Like a sap, I follow the arrows until I hit a dead end. American kitsch combined with a cheesy false alarm.

Trying to shake a bad mood, I meander over to the ghost town that marks the other frontier of the Texas Panhandle. Here is Glenrio, killed off by the opening of the interstate. Old 66, a pavement which is punctuated in town by a vestigial slab divider, simply peters out into red dirt and potholes. A cemetery for wrecked cars makes a nice counterpoint to a wooden water tower leaning at a drunken angle, downstreet from a wrecked coffee shop. This used to be the site of the celebrated "First and Last Motel in Texas," and some shards of the old sign can still be seen on the abandoned skeleton of the building, which is a dried-out mausoleum preserving the faint redolence of countless crossborder fornications. For additional Larry McMurtry-like eeriness, the spot is so negligible and dilapidated and done-in that my radio "seeker" can't pick up a signal in any direction. A deep calm descends upon me at this discovery, and I just sit listening to the insects until a nearby dog gets up the courage to break the silence. If I roused myself from the enveloping torpor and threw him a stick, it would fall into the next-door state.

This is the New Mexico border, which jauntily announces that I'm now on Mountain time and, as if to press home the point, gradually discloses a handsome mesa hoving into view on my left. At last, some landscape after the flatlands. The mesa also signals the old town of Tucumcari, which is a place of motels, a strip of motels, a grid of motels, a theme town of motels.

You could stay in a motel while you looked for a motel room. A motel owners' convention would be a distinct possibility. Queen of the flops is the Blue Swallow Motel, which preserves the old and charming and discreet idea of an individual attached garage, placed like a pigeonhole next to each room. The buildings are pink. The garage doors are blue. Down by the wrong side of the railway tracks, I cheer up further by engulfing two bowls of cheap but gorgeous chili at Lena's Cafe, where Spanish is the tongue and where a flyswatter is placed wordlessly next to my plate. I am politely asked twice, "Are you sure?" The first time is when I ask for a second bowl. The second time is when I leave a $3 tip on an $8 check. A large color poster of Jesus Christ is on the outside of the men's-room door: somehow it's a different Jesus from the one featured in the Protestant highlands and lowlands a few hundred miles back.

The road through Albuquerque mimics an 1849 gold-rush trail, cut in a hurry for those seeking to reach the California diggings from Arkansas and other Dixie territories. Extreme modernity imposes itself at the Kirtland Air Force Base, on the fringe of town, which houses the National Atomic Museum, the nation's principal destination for those who like collectible cards of weapons of mass destruction. I always strive to avoid writing about the "land of contrasts" when I travel, but here in the most ancient settled part of America—there is an Indian pueblo at Acoma which archaeologists theorize has been continuously inhabited since about A.D. 1150—the nuclear state was born, and its weaponry first designed and tested. Every effort has been made to leach both of these historic dramas out of the roadside scene: the wigwam-shaped tourist stops and gas stations are parodic and chirpy, and the main reminders of the militaryindustrial world are the long, anonymous trainloads over to the right, which according to local opinion are rumbling across their high desert from the huge bases in California. The motels and shops prefer to present this as a relic of the old Santa Fe Railroad days, when trains had cowcatchers on the front rather than suspicious materials in the boxcars. There's an extremely short strip of old 66 around here, perhaps the shortest of all, that preserves the old steel bridge across the Rio Puerco. The Puerco is a dry gulch, or is at this time of year.

A big rampart of red rock starts to dominate the same right-hand view, and also begins to look familiar, which, I suddenly realize, it would to anybody who had viewed an old Western movie. (You've seen it, probably just as a bristling rank of filmic feathered warriors appears at the summit.) This ridge also marks the Continental Divide, where rainfall—everything hereabouts is decided by water—makes its decision about whether to flow east or west. The elevation approaches 7,000 feet and the wind can be fierce. As I get near to Gallup, a sign on a bridge advises me that GUSTY WINDS MAY EXist—a fascinating ontological proposition. Here, between the Navajo and Zuni lands, is the town that has some claim to be the capital of Native America. But it too is utterly buried in an avalanche of kitsch, with more bogus beads and belts and boots on sale than you can shake a lance at. I find that "folkloric" displays of the defeated and subjugated have a marked tendency to induce diarrhea at the best of times, but there is something especially degrading and depressing in the manner of all this: I prefer the United States of America to the idea of Bronze Age tribalism, yet surely a decent silence could be observed somewhere, instead of this incessant, raucous, but sentimental battering of the cash register. On many stretches of road, you can barely see the primeval hills for billboards and pseudo-tepees. The El Rancho Hotel in Gallup is actually one of the more restrained evocations of the oldish days, with only a thin veneer of neon surmounting its basic structure of wooden fittings and weathered exterior. However, this is more like an outpost of old Hollywood, where the stars of those movies filmed in and around nearby Red Rock State Park could get a decent meal and some comfort. The brochure is the only one I've ever seen that claims both Ronald Reagan and his first wife, Jane Wyman, as guests (it doesn't state whether together or separately), and every room is "starred" with Alan Ladd, Paulette Goddard, and so forth. I'm billeted in the one named for Carl Kempton, whoever he was, right next door to Rita Hayworth. California, which has seemed so far away for so long, suddenly begins to feel attainable. The annual Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial, which sounds like the corporate or casino or cable version of a clan gathering, was soon to get under way in the town. One might have expected this to be an occasion for even more cashing in, but all I can tell you is that in Gallup, with its hard and acquisitive glitter and its resolute face to the future, I met with many trivial moments of hostility. Roadside America is always polite, even when the politeness is synthetic, and almost always friendly. But here—and I don't think it was the car—it was the monosyllable and the averted glance, even when I was only asking directions. I couldn't tell whether I was running into a superiority complex, or an inferiority one, but I was glad of a thick skin. I wasn't going to buy anything anyway.

The town of Clinton has the best of the "66" museums, featuring an antique T-Bird and an overloaded Okie truck.

Bleakness stayed with me until I traversed the Arizona border and turned off, near the absurdly named "Meteor City," to view this continent's most astonishing crater. Here, some 50,000 years ago, a huge piece of iron-and-nickel asteroid slammed into the desert with enough force to transform graphite into diamond. It displaced 175 million tons of limestone and sandstone, and left a beautifully rounded hole, 570 feet deep and 2.4 miles in circumference. We have a silly way of trying to make human scale out of these majestic things, so, O.K., if it were a football stadium, I am informed by the "Meteor Crater Enterprises Inc." brochure, it would seat two million spectators for 20 simultaneous games, and include the Washington Monument as a flagpole in the center. I saw, clustered around the telescopes on the rim, the largest concentration of that special tourist species—those who wear shorts and shouldn't—that I have ever witnessed outside Disneyland. The swaying, pachydermatous haunches of my fellow creatures seemed bizarrely transient and vulnerable in the context. Perhaps in reaction, I found it impossible to stand on the edge without looking up rather than down—though down is very impressive—and trying to picture what the last seconds before impact could conceivably have been like. It doesn't take long to give up on the endeavor: try imagining the apocalypse. NASA trained in this crater for a lunar dress rehearsal. And the moon itself was probably the result of a much more dynamic collision with our planet. The whole solar system is the outcome of similar smashes, as probably was the extirpation of the dinosaurs, whose jokey features are much exhibited locally to capture the kiddie market. It all bears out what I've always said, which is that there can be no progress without head-on confrontation. However, an impact site of this magnitude lends a bit of perspective. Large meteorites or asteroids get through the atmosphere of Earth about every 6,000 years or so without burning up, so we are about due for another smack. Go and see Arizona while you can.

On the road into Flagstaff the Corvette gives a slight whinny as it senses a rival. Off to the left is what looks like an old Rolls-Royce, parked outside yet another wigwam-shaped souvenir store. On inspection, it proves to be a beautiful Austin Princess, still with its English license plates, standing aloof in the broiling sun. Inquiries within disclose that it's the property of the store owner, who proudly reveals that he bought it out of a garage in nearby Winslow, where it had been sitting undriven for years. He has no idea how such a vintage masterpiece, with its original ID, came to be hiding in the Arizona desert. Giving Flagstaff a bit of a miss—too metropolitan for my needs—I venture down the hairpin forest road to Sedona, which offers me the most slender and cathedrallike mesa columns as they are noosed in the rays of evening sun. Sedona has become the Aspen of the area, with resort hotels and golf courses and fancy restaurants in phony Spanish courtyards, but the air and light and verdancy are astoundingly refreshing after the high desert.

"Don't forget Winona," urges the song. Winona is put in, I can promise you, only because it rhymes with Arizona. But then, so does Sedona, and you can really find Sedona, whereas you drive straight through Winona without noticing it, and can't even identify it when you turn back. It's become a Flagstaff sub-burg, another featureless location. But the old 66 between Flagstaff and Kingman is one of the best and easiest stretches of the remaining pavement, and it's deliciously quiet and still and untraveled. On one fence post I see a beautiful motionless bird, which to my trained ornithological eye resembles either a very large hawk or a medium-size eagle. It waits imperturbably for a rodent or other small mammal to break cover and make the crossing. It returns my gaze without flinching. Turning away from feral nature, I find this is the only road on which the tradition of the BurmaShave ad survives. In the interwar years, the makers of that amazingly successful brushless cream evolved the idea of putting a line from a jingle every half-mile or so, thus forcing motorists and their families to keep pace with the rhyme. So you would see, punctuated at intervals, lines such as "If you / Don't know / Whose signs / These are, / You can't have / Driven very far. BurmaShave." Or "Shaving brushes / You'll soon see 'em / On the shelf / In some / Museum. Burma-Shave." Old-timer accounts of 66 never fail to cite this nostalgic feature. On the road into Seligman, the tradition has revived in the form of a public-service announcement. Over the course of a couple of miles without another car in view, I learn in sequence that: "Proper distance / To him was bunk / They pulled him out / Of some guy's trunk." Can't be too careful.

Seligman itself is one of the smallest and sweetest stops on the Route, and aptly enough its centerpiece is a one-chair barbershop, owned and operated for decades by Angel Delgadillo, a senior citizen with a huge, toothy smile who founded the original Historic Route 66 Association and probably stopped his hometown from going the way Texola and Glenrio did when the road passed them by. These days it's tourism or death, or both. Angel is cutting chunks from the mane of a Christ-bearded hippie type when I walk in, and has the practiced air of an unofficial mayor and ambassador, with a roomful of visitors, so I amble down to the Black Cat Bar and brown-bag store. Here, the friendly Tim tells me that he was moving his truck and his dogs from New Orleans to Washington State about a year ago when he broke down in Seligman and decided to stay. It's nice for the dogs, you can save money, and people are friendly enough, though in a town of fewer than 1,000 souls you have to watch out for "the Peyton Place side of things. Everything is everybody's business." All the time I am in Seligman, with its Marilyn Monroe posters and old-style gas pumps, there is a train longer than the town standing at the nearby station.

Kingman is the last major stop before the real desert begins, and here too the kold Santa Fe system makes its point with a noble steam engine mounted like a fish out of water? like a train off the rails?-at the edge or a park. There was a random, decent full-service restaurant as well, named Calico's, where a hauntingly beautiful Spanish waitress had a good sense of the times and distances ahead, fueled me with a rich variety of calories for the ordeal to come, and warned me that the California Highway Patrol was a good deal more picky than the New Mexico and Arizona boys. (The speed limit varies from 75 to 65 as you cross state lines: the limit on the old 66 road is a euphonious 55, and the optimum overall is 77 unless you have a Corvette rearing and plunging under you.)

Steinbeck wrote of his desperate Okies as they left behind "the terrible ramparts of Arizona" and attempted to cross the desert at night because of the appalling glare and heat, and I try to make up time across the anvil of pain that stretches before me. A baby twister gets up outside Kingman and struggles to become menacing. But the turnoff sign to "London Bridge" proves too seductive, and I make the detour to Lake Havasu City, which regularly posts some of the highest temperatures in the continental U.S. I remember reading in my boyhood that some idiot had taken down a bridge over the Thames stone by stone and reerected it in the desert, and here it all is. On the edge of a lake formed by the Colorado River, an artificial stream has been created, and the old gray span of London Bridge, which had survived fog and drizzle and German bombs between 1825 and 1968, is draped across it. This is the grand scheme of Robert P. McCulloch Sr., a chain-saw and oil and real-estate king who bid on the bridge and got it shipped across the Atlantic, shrapnel scars and all. Apparently he believed that he was getting the spires and drawbridges of Tower Bridge and didn't discover his error until too late. (The one he got was a descendant of the star of the old song "London Bridge is falling down.") But it would be wrong to call this McCulloch's folly, as one is tempted to do. Last year more than one million people made the stop. The howling absurdities of desert-oasis Anglophilia dwarf the collector's-item Austin Princess near Flagstaff as I pass the "Canterbury Estates Gated Community"—gated against what? the Navajos?—and view the Jet Skiers on "Windsor Beach" and the shoppers at "Wimbledon Goldsmiths." Union Jacks hang limply in the heat next to Old Glory. There's a "pub," of course, and some red telephone boxes and a red double-decker London bus. Yet the beer isn't warm enough to be authentic, and while the weathered old stone may last longer in this arid frazzle, it still sags a bit. The genuine fake is starting to become a bit of a theme along here.

Sixty-six could survive only by selling itself...another coffee mug, another T-shirt, another line of cheap "Route 66" jeans.

Returning to the main road, I pass through Yucca, near Yucca Flat, where the open-air nuclear tests of the 1950s and 1960s had many glowing and electrifying effects, of which the best are captured in the movie Atomic Cafe. Which would have been the more impressive and terrifying to see: the landing of the meteor that turned graphite into diamond, or the detonation of man-made devices that could fuse sand into glass? In 1955, John Wayne was playing Genghis Khan, possibly the very worst of his roles, downwind from Yucca Flat during the tests. Of those on the shoot, he was only the most famous one to get lung cancer later on: that location was a culling field. Susan Hayward, Agnes Moorehead, and Dick Powell were also to succumb. Can Wayne have been fatally poisoned by the military he so adored? According to a recent biography, it looks as if that was the way it was. This sinister, worked-over sandscape has a weird antenna on every other hill, and the alien effect persists as the Colorado River cuts again across the wilderness, appearing rather shiny with false modesty after its epic work in designing and forging the Grand Canyon less than a hundred miles upstream. California! Here I come. But right away I am forced to pull in to a state "Inspection Station," as if meeting a frontier in Europe. The boredom and conceit of this—it's the only such barrier in all the eight states of Route 66—plays to the Californian narcissistic fantasy of being a semi-independent nation, with its own economy. But it also provides a reminder of the cruelty with which the state treated the migrants of the 1930s, tearing up their driver's licenses and turning them back as vagrants, until the courts finally put a stop to it. The gray-haired taxpayerfunded lady at the barrier waves me through after saying she preferred the color of my car to its make. Who the hell asked her?

The Mojave Desert is almost frightening. No—it is frightening. It's easy to see why the surviving Okies wanted to cross it at night, and not just because of the annihilating heat. In the dark, you wouldn't have to see the grim, dirty hues of the rock and the soil, and the endless, discouraging length of the road stretching ahead forever. There is something infinitely wearying about seeing one summit after another prove to be an illusion, range replacing range with ruthless monotony. The mile markers seem to slow down—surely I came farther than that? The sensation, of moving fast but never escaping, is dreamlike and hypnotic but not in a relaxing way, and the knowledge that this is homestretch territory makes me superstitious about a last-minute mishap. Many of the turnoffs on the map are to vanished places that are only names, and the truth is that somewhere along this harsh and lifeless highway the old Route 66 just dies. It disappears into the trackless mess of suburban California as Los Angeles spreads out to embrace and claim it, and the last real stop is in Barstow, where the old road is blocked at the edge of town by a huge Marine base. Here at the El Rancho motel, built out of old railroad ties and festooned with 66 memorabilia, I mentally announced journey's end. The motel is indeed journey's end for a number of other people; in its rear court I was offered crystal meth and the services of a haggard and punctured whore before I could get out of the car. Snarling and shivering figures mingle with those to whom blank, inert amiability has become a signature. Down at the end of lonely street ...

Bobby Troup's original ditty was better than perhaps he knew. He borrowed from the Homeric tradition by drawing a word-picture treasure map with memorable and rhyming place-names, an Odysseylike mnemonic for the American Dream. And he and Cynthia, who suggested that crucial rhyme in the refrain, were able to buy a house in California within weeks of the release of the song. Postwar optimism drew freedom of travel, extra dough, and sexual emancipation. Those words and that music touched such a nerve that I don't think I met anybody of any age last summer who, on hearing my plan, failed to respond with something like "Get your kicks, huh?" But try listening to the newer songs that mention the nation's most beloved road trip. On "Lost Causeway," Jason Eklund sings, "Get your kicks on what's left of 66," and says, "So follow state and homespun signs, leading on this historic route / Take a grab at the corporate crapola where history has been rubbed out." (Interestingly, he preserves the eastern pronunciation of "route.") Picking up on the cynicism of the commercialized Indian reservation with its tax-free cigarette bonanzas, he suggests "Get your fix ..."

The Red Dirt Rangers in their song "Used to Be," which has a tang of Springsteen's "My Home Town," speak of "holes in the roof and weeds by the door" of the trailer where the motor courts once stood, while the Mad Cat Trio intones the words "Get your kicks" with positive sarcasm. The Dusty Chaps, in "Don't Haul Bricks on 66," put their advice—"Route 66 ain't the way to go"—on the same level of obviousness as "Don't go pissing in the wind" and "You know the white hats always win." The music didn't quite die on this road, but it changed from celebration to melancholy and disappointment. Perhaps it all went when the last hitchhiker gave up, or was banned. Larry McMurtry was certainly right, in Lonesome Dow, to point out that once something is sold as "the Wild West" it means it's become domesticated. The luminous Robert Crumb registered a similar point in a 12-frame cartoon, showing the evolution of a roadside scene from a setting with a road to a place where the road was the setting. The old 66 tried to be genuinely different from the new for a while, but it could survive only by selling itself as different, and those very sales tactics meant that it had to become the same. It's another coffee mug, another T-shirt, another line of cheap "Route 66" jeans from Kmart. The living bits of antique 66 are colonies of the new interstate, and the dead bits are, well, dead. I doubt that Texola or Glenrio will still be there if I travel that way again; outside Glenrio, I could already see and hear the earthmovers. In California the 50-year-old Trails Restaurant, a 66 holdout in Duarte, was demolished almost as I drove by. You never step into the same river twice. All travel is saying farewell. Most voyaging in the United States has become either impossible (by rail) or a misery and a humiliation (by air) or a routine (by roads with no individuality). No poet has yet attempted to say what this defeat means for the American idea. But the melancholy is all around us, transmitted on frequencies that nobody can possess. After one last, brief, yearning sweep along Sunset, I did what I would once have bet I could never do, and roared down Rodeo Drive in a brash Corvette. The window-shoppers barely looked up. The drop-off point for my mettlesome steed was just at the corner of Wilshire. I tethered it, patted it, handed over the keys, and forgot to look back.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now