Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowKEROUAC'S LONESOME ROAD

James Wolcott

King of the Beats, Jack Kerouac wrote the bible for their cult of vagabond freedom, then fled, reeling, from the fame it had brought him. But 30 years after his slow alcoholic suicide, Kerouac's On the Road is still being discovered, stolen, and loved

Jack Kerouac, who died 30 years ago this October at the age of 47, committed suicide on the installment plan. He took his time on the checkout line, drinking himself numb. As a young man Kerouac was blessed with a handsome jaw, a dark, virile Superman forelock, an athletic build (he played football for Horace Mann), and a raft of life experience which set him apart from the baby owls in academe trying to emulate T. S. Eliot's dry-sherry manner. (Such as Allen Ginsberg, whom he met in 1944 at Columbia University, where Ginsberg was a student of the distinguished literary critic Lionel Trilling, the J. Alfred Prufrock of the English department. Kerouac met the other member of the Beat trinity, William Burroughs, later that year.) Kerouac's most famous achievement as a writer—On the Road, one version of which was typed on a 120-foot scroll of wire-service paper during a threeweek Benzedrine-and-caffeine binge—was as much a physical feat as a creative splurge, the work of a powerful locomotive. Add to this a movie-star name (it even rhymed!) and a tough, wounded masculinity reminiscent of Marlon Brando, and it was no wonder fame found Kerouac a natural. But far more swiftly than Brando, Kerouac turned to bloat. As he wrote in a ditty called "Rose Pome," "I'd rather be thin than famous ... / But I'm fat. Paste that in yr. Broadway Show."

The reading of On the Road has become a classic rite of passageit's an initiation into a mythic tribe.

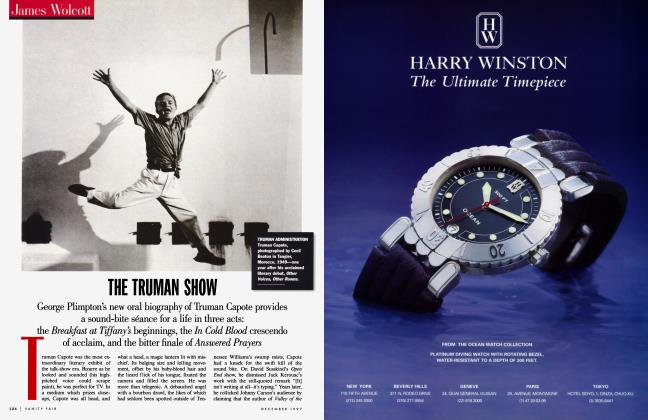

When Kerouac died on October 21, 1969, of massive abdominal hemorrhaging in St. Petersburg, Florida, where he was visiting his mother, he was fat and mostly forgotten. "He was a very lonely man," his third wife, Stella, told the Associated Press. The portrait of Kerouac's last days was captured in an illustration for Esquire magazine (March 1970) which showed a beer-gut hasbeen slumped in an armchair surrounded by a stack of National Reviews and a scatter of empty bottles: the king of the Beats on his crumb-bum throne. Once a charioteer hurtling toward the horizon, his car radio tuned in to the cosmos, Kerouac had degenerated into a test model for All in the Family's Archie Bunker, grumbling about hippies, Commies, and Jews. The year 1969, remember, was also the year of Easy Rider, whose shock climax of bikers bushwhacked by rednecks spelled the end of the wind-whistling romance of freedom and acceptance celebrated in On the Road. At the time, it seemed plausible that his rebel yell would fade into a historical footnote, but 30 years after his death, Jack Kerouac still broods over the landscape, larger than ever. Kerouac lives.

Not only does he live in the minds of readers, he remains a wanted man, one of the few writers worth stealing. Like a saint's relics, his books attract thieves. At the St. Marks Bookstore and the Union Square Barnes & Noble in lower Manhattan, his

paperbacks are so prey to shoplifting that they're kept behind the counter. Skyline Books, a secondhand store in Manhattan's photo district, offers a section of Beat memorabilia, a humble shrine which occasionally stocks back issues of Holiday, Evergreen Review, and Escapade containing articles by Kerouac. The Kerouac cult is part of the larger unquenchable fascination with all things Beat. For a group of writers who exalted and peddled drug highs, jazz sensations, spontaneous kicks, transient moods, Oriental-rug visions, and other wordless transports, it's ironic that they not only amassed mountains of their own pesky words but also inspired a beaver community of hangers-on, historians, critics, former lovers, and idolaters whose output threatens to dwarf the original peaks. Hundreds of titles have been published on the Beats from every personal-critical-psychosexual angle. A larger irony, given how heavily the Beats stressed the Zen Now, is the persistent backwash of nostalgia they left behind, a beckoning piano concerto of typewriter keys striking the page rivaled only by Hemingway's Paris in the 20s. The Beats have proved such an enduring beacon and monument on the pop-culture scene that even those who might be called children of the Beats, such as Patti Smith and Bob Dylan, have become sacred elders, presiding over their own flock of crows. The permanent Beat cult isn't strictly a literary phenomenon, even though the reading of Howl, Naked Lunch, and On the Road has become a classic rite of passage for every restless kid staring out the window at school. It's an initiation into a mythic tribe.

Kerouac was the heart and soul of the Beat operation. He coined the term "Beat"—beat as in worn, beat-down; beat as in beatific—and was its true apostle. William Burroughs, with his banker's suits and vampire demeanor, was the surrealist of the group, dishing up pristine cuts of rotting carcasses in Naked Lunch. Allen Ginsberg was the chief propagandist, a Jewish Buddhist huggy-bear devoted to good works and street theater (the attempt to levitate the Pentagon in the 1967 anti-war march, a quixotic magic act immortalized in Norman Mailer's The Armies of the Night, had Ginsberg written all over it). The great outlaw inspiration was Neal Cassady, Kerouac's model for Dean Moriarty in On the Road and the title character of Visions of Cody. An autodidact, pool shark, jailbird, satyr, and roustabout, Cassady bulleted through life with none of the inhibitions or Sorrows of Young Werther that plagued undergraduate bookworms like Kerouac and Ginsberg. (Burroughs, an old soul with no illusions to rend, always plotted his own pirate course.) Without the exampie of Cassady goosing them into action, the Beats might have remained a Romantic offshoot, a homegrown version of Rimbaud, Blake, and Shelley syncopated to the incantatory lines of Walt Whitman, never getting beyond the chatterbox stage.

The fame that most writers chase like an ice-cream truck sent Kerouac reeling in the other direction.

Kerouac led the way out. He did what Cassady was unable to do—translate fugitive experience into what the critic and Beat-scene maker Seymour Krim dubbed Action Writing. In On the Road (1957), Kerouac piped the license and movement he found in Cassady through his own tenor-sax prose. It's become fashionable to say that On the Road doesn't "hold up," that it's dated and sentimental and backtracking.

The issue of whether On the Road holds up is irrelevant to a kid cracking it open for the first time; to him (and it's usually a him, Kerouac's disciples being overwhelmingly male, in my experience), the novel isn't a literary artifact to be judged against the inner gold of other artifacts, but a personal saga and broadcast that bypass normal communication. To newbies, Kerouac's exploits aren't filtered through layers of critical analysis but come at them pointblank, just as Ginsberg's haranguing lines in Howl manage to hit new generations of readers full blast. Kerouac writes as if he's right there with you, a fellow passenger. (Kerouac himself seldom drove.)

"Everything in life is foreign territory. Kerouac—he's my teacher. The open road, my school."

—Xander (Nicholas Brendon), brandishing a copy of On the Road in an episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer.

It would be unfair to leave the patronizing impression that On the Road appeals only to untapped minds. I recently reread it, not having dipped into it since high school, and was bowled over by its superabundance of incidents, energy, open-pored passion, and canine devotion. Like his literary hero Thomas Wolfe, whose cathedral detailing and rhetorical swollen glands provided the model for Kerouac's first novel, The Town and the City (1950), Kerouac had America mapped in the palm of his hand. (Together, Wolfe and Kerouac helped father Bob Dylan, who rattles off placenames in his lyrics like a train conductor.) The lifeline in this palm is the Mississippi River, "the great brown father of waters rolling down from midAmerica like the torrent of broken souls." As Kerouac's Sal Paradise caroms like a pinball from one bank of city lights to another ("with the radio on to a mystery program, and as I looked out the window and saw a sign that said USE COOPER'S PAINT and I said, 'Okay, I will,' we rolled across the hoodwink night of the Louisiana plains ... "), the novel flickers with snapshots of the poor and neglected in an ongoing montage which evokes not only Wolfe's night-watchman reveries but also the photographs of Robert Frank. (Kerouac did the foreword for Frank's The Americans, the most evocatively shrouded book of postwar photography.) Although On the Road was published in 1957, its action takes place 10 years earlier, tinged with a sepia-toned longing for a pre-TV America which retained vestiges of vagabond individuality. On the Road is a paradise-lost elegy but—here's its secret—a buoyant one, not some limp flag of commemoration.

The energy is rooted in misfit comedy. Often forgotten today is what a funny writer Kerouac was. The humor doesn't spout from dyspeptic one-liners (Burroughs's specialty) or facile absurdism, but finds release through the sheer collision force of all these human cannonballs smacking together. The section in On the Road where we're introduced to Bull Lee, the William Burroughs character, is a comic lithograph of Tristram Shandy-like eccentricity, from the pet ferret Lee used to keep in his "well-appointed rooms" to his drug tinkering ("He also experimented in boiling codeine cough syrup down to a black mash—that didn't work so well") to the following psychological checklist:

He had a set of chains in his room that he said he used with his psychoanalyst; they were experimenting with narcoanalysis and found that Old Bull had seven separate personalities, each growing worse and worse on the way down, till finally he was a raving idiot and had to be restrained with chains. The top personality was an English lord, the bottom an idiot. Halfway he was an old Negro who stood in line, waiting with everyone else, and said, "Some's bastards, some's ain't, that's the score."

Driving fast and fighting sleep, Kerouac's road warriors are trying to out-race their own nervous breakdowns and demons as they gulp the scented night air. The novel eventually veers off to Mexico, as all salvation tours must, because that's where the madonna-whores are, tiny crosses dangling between the tawny bosoms on which our heroes can rest their mangy heads until it's tequila time.

Despite that legendary scroll, On the Road wasn't published hot out of the typewriter. The novel took years to gel; draft after draft was rejected by various houses, the standard edition trimmed and massaged into shape by the editor and critic Malcolm Cowley over Kerouac's foot-dragging objections. For years afterward, Kerouac and Ginsberg complained that Cowley's commonsensical Yankee approach took the snap out of the novel's serpentine spirit, taming its pulsating swing for a more straight-ahead story line. Instead, they should have shown some gratitude, for On the Road prospers and endures precisely because Cowley found a way to bottle the lightning. It's the one Kerouac book that seems fully assembled and guided. In a letter to John Clellon Holmes, the author of the Beat novel Go, Kerouac championed "wild form, man, wild form"—but without an authorial design or editorial oversight Kerouac's writing tended to taper off into wispy formlessness. Even novels graced with epiphanies of pencil-sketch portraiture (The Subterraneans) or nature worship (The Dharma Bums) suffer from a noodling-doodling lack of dramatic emphasis. It's like listening to a musician tune up, only words are more than notes and sounds: they signify and convey meaning. Without somewhere useful to go, they lie there orphaned, mere jottings, providing evidence for Truman Capote's famous gibe, "It's not writing, it's typing." For all its hoots and yelps, On the Road is undeniably writing.

With the publication of On the Road, Kerouac awoke one morning to find he had won the literary lottery. After a rave review by Gilbert Millstein appeared in The New York Times, Kerouac's publisher arrived bearing champagne, and the phone began ringing with congratulations. Kerouac, however, wasn't ready for his screen test. Where Burroughs and Ginsberg knew how to joust with the press and were foxy enough to create brand-name personae (Burroughs was doing jeans commercials shortly before he died), Kerouac stumbled into traffic like a tourist, lost in the oncoming lights. His radio and television appearances took mumbling beyond Method acting (he sat and moped), his public readings were amateur hour (he never developed Ginsberg's bardic showmanship), and a famous panel discussion featuring Kingsley Amis, Ashley Montagu, and James Wechsler, among others, reduced him to clown antics. He seemed to regard tabloid ink as if it were his own spilled blood. The fame and all its goodies that most writers chase like an ice-cream truck sent Kerouac literally reeling in the other direction. His drinking intensified, turning Superman into Stuporman, his blackouts a foolhardy way of blotting out the world's now insatiable demands. At the height of the On the Road hullabaloo, Kerouac told Jerry Tallmer of The Village Voice that he was splitting this crazy scene. "I'm going down to my mother's in Orlando. Always go back to my mother. Always."

A grown man living with Mom, what could be squarer? Who did he think he was, Liberace? (Kerouac's mother was no sweetheart, either—Memere read her son's mail like a prison snoop, refused to let Ginsberg into her house because he was a drug user and homosexual, and was so nasty that even the unflappable Burroughs considered her a minor form of evil.) Kerouac wasn't kidding, though. He unplugged himself like a neon sign. The drastic U-turn Kerouac made in his life—from gypsy preacher of Beat prophecy ("a White Storefront Church Built Like a Man, on wheels yet," in Seymour Krim's majestic estimation) to stay-athome hermit—has a pathos and rotting integrity worthy of a Eugene O'Neill play set in a dim interior. One of the reasons Kerouac is such an unresolvable case three decades after his death is that by chucking it all he turned his hunched back not only on fame but on the entire notion of a literary career. Even writers who have shrouded themselves in secrecy (J. D. Salinger) or move among us like the Invisible Man (Thomas Pynchon) have produced a recognizable body of work which they zealously safeguard. Kerouac, however, seemed to tear up the books he had within him into many pigeon scraps. Alcohol may have so hollowed him out that all he could hear were echoes of what he had done before and of those he had left behind. Jack McClintock, a newspaper reporter who visited Kerouac in St. Petersburg in his last few months, speculated in Esquire: "It was almost as if Kerouac, in the last years, had burrowed farther and farther back into his personality, back into the dense-packed delights and detritus of a fife, and then turned around, and was peering out at the thronged world through the tunnel he made going in. Perhaps being back there clarified his sight in some ways, focused it more clearly on the things he could see. Perhaps it just gave him tunnel vision. I don't know."

After Kerouac died, his body was shipped to Lowell, Massachusetts, for burial. Vivian Gornick covered the funeral in an affecting piece for The Village Voice, recording the dignity of Allen Ginsberg and his lover Peter Orlovsky, the generous heft of the townspeople, and the sight of Kerouac in his open casket, waxy and remote, "stripped of all his ravaging joy." Kerouac seemed roadkill from a bygone era when he was put to rest, but over the succeeding years he rose to the stature of Hank Williams and James Dean and other saints of the celestial highway. Ginsberg and Dylan made a pilgrimage to his grave site during the Rolling Thunder tour of 1975, providing one of the few grace notes to the film Renaldo and Clara.

In 1988 the city of Lowell erected an elaborate memorial for Kerouac, an event which had the neoconservative commentator Norman Podhoretz shaking his fist at the temerity of officials honoring this hooligan. As a climbing young critic, Podhoretz had written a much-reprinted essay 30 years before called "The KnowNothing Bohemians," which accused the Beats of being storm troopers in sandals (their marching orders: "Kill the intellectuals who can talk coherently, kill the people who can sit still for five minutes at a time, kill those incomprehensible characters who are capable of getting seriously involved with a woman, a job, a cause"—kill, kill, kill!). So he at least had the virtue of being a consistent crab. To Podhoretz and other cultural declinists, the Beats were nihilists responsible for the hedonistic disarray of the 60s, never mind that Kerouac himself repudiated Abbie Hoffman and his Yippie followers. He once removed an American flag Allen Ginsberg had wrapped around his, Kerouac's, shoulders like a shawl, folding it properly, and explaining, "The flag is not a rag." Which didn't deter Podhoretz from fuming in the New York Post, "Dropping out, hitting the road, taking drugs, hopping from bed to bed with partners of either sex or both—all in the name of liberation from the death-dealing embrace of middle-class conventions_This, then, is what the City of Lowell is inescapably honoring in building a monument to Kerouac," those heathens.

What really bothers Kerouac's killjoy detractors is that a memorial for the Beat King is a victory for reckless creativity over critical rigor. In Podhoretz's Manichaean mind, it's reason, coherence, tradition, Judeo-Christian ethics, and monogamous maturity versus risk, itchy impulses, immediacy, Eastern mysticism, and dirty feet on a bare mattress, and guess what?— his side lost. O, the inequity of it all, mastering the nuances of modernism only to be shunted aside by this bony army of hairy armpits! Deeper than the Culture War or an Alamo defense of literacy and even more vexing to those suffering from Beat antipathy is the knowledge that replenishing waves of readers love Kerouac—no other word will do—love him despite himself, despite his drunkenness, racist insults, and unreliability (he's the deadbeat dad everyone's decided to forgive). Kerouac is loved and mourned for the loneliness that penalized him most of his life and for the rugged reflection he left in the hard surface of American life. "America is where you're not even allowed to cry for yourself," Kerouac observed in Visions of Cody, and he may have been the last American writer without a trace of cynicism or protective guile. (Of those who came after, only Raymond Carver tiptoed around similar heartbreak.) It was a tragedy for him and for American fiction once he was no longer able to articulate the tempests he felt. He withdrew, suffered like a saint, and prematurely aged, yet some part of him stayed rockabilly to the end. "The only time I saw him with his hair combed," Jack McClintock wrote in Esquire, "was in his casket."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now