Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

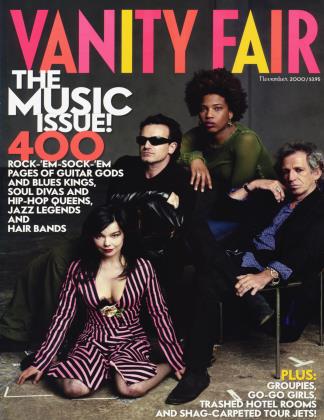

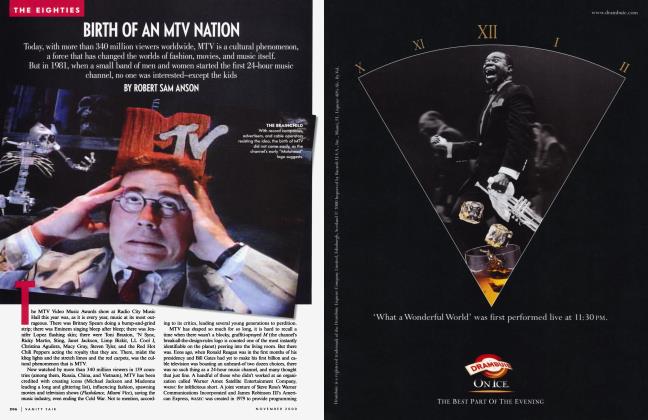

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowSaxophonist Charlie Parker changed the house of jazz forever, winning the awed allegiance of contemporaries such as Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis. But, as the author’s companion book to Ken Burns’s new PBS series on jazz reveals, Parker was torn between his horn and heroin, in a war that cost music its bebop genius

November 2000 Geoffrey C. WardSaxophonist Charlie Parker changed the house of jazz forever, winning the awed allegiance of contemporaries such as Dizzy Gillespie and Miles Davis. But, as the author’s companion book to Ken Burns’s new PBS series on jazz reveals, Parker was torn between his horn and heroin, in a war that cost music its bebop genius

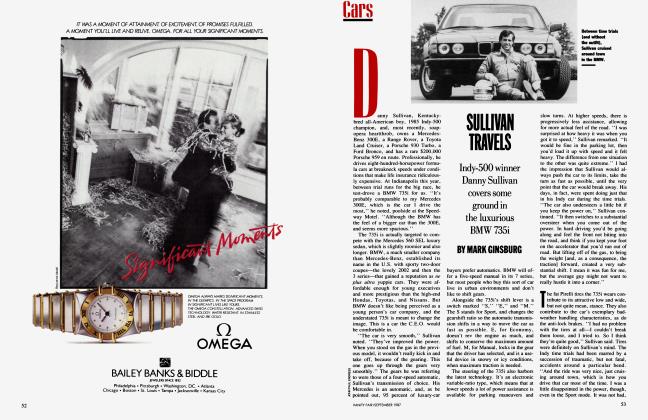

November 2000 Geoffrey C. WardOn January 9, 1942, a little more than a month after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Lucky Millinder’s orchestra was well established on the Savoy Ballroom bandstand once held by Chick Webb. His band, propelled by the piano of Bill Doggett, the bass of George Duvivier, and the drums of Panama Francis, was a special favorite with Harlem dancers, and when a new outfit from Kansas City led by Jay McShann arrived to play opposite them in a battle of the bands that evening, Millinder’s men were not worried. The sight of the out-of-towners—all young, all dressed in cheap Sears, Roebuck suits, all badly rumpled after the cross-country trip by car—appalled the Ballroom’s manager. It was “the raggediest-looking band” he’d ever seen, he told McShann. “This is New York City, boy, this isn’t Kansas!” And, just before the contest began, Millinder’s elegantly outfitted musicians sent McShann a note meant to rattle him further: “We’re going to send you hicks to the sticks.”

Excerpted from Jazz: A History of America’s Music, by Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns, to be published this month by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.; © 2000 by the Jazz Film Project, Inc.

For three half-hour sets, the two bands played more sedately than usual, each listening carefully to the other, assessing strengths and weaknesses. “We just kinda laid back,” one of McShann’s men said. Then Millinder launched into a series of elaborate arrangements meant to show up the out-of-towners. “Heavy stuff,” McShann said, but “Lucky wasn’t swinging.” It was the opening McShann had been waiting for. “As soon as he hit his last note we fell in,” he said. “When Jay turned his boys loose,” one New York musician remembered, “he had hellions working. Just roaring wild men.” McShann’s band, like Count Basie’s, stomped the blues and specialized in loosely organized head arrangements that could be expanded almost infinitely as long as dancers were responding. “This was a thirty-minute number,” McShann said, “and the people screamed and hollered for another thirty minutes.” Millinder and his men stood by fuming as the Savoy dancers called for encore after encore by the band their leader had dismissed as “those western dogs.”

The McShann band was tight, the blues it played irresistible to dancers. But its skinny, 21-year-old alto-saxophonist, Charlie Parker, was something else again. He had not yet fully developed the style that would make him the most influential soloist since Louis Armstrong. But he already sounded very different from Benny Carter and Johnny Hodges, the alto-saxophone masters musicians then most admired. His sound was harder than theirs, virtually without vibrato, and he had found a fresh way to phrase the inexhaustible musical ideas that already seemed to tumble from his horn without apparent effort.

Only Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington can be said to have made greater contributions to the music.

Musicians hurried to the Savoy to hear him. When “Charlie got up and played,” recalled the trumpet player Howard McGhee, then a member of Charlie Barnet’s band, “we all stood there with our mouths open, because we hadn’t heard anybody play a horn like that.” He “was playing stuff we’d never heard before,” Kenny Clarke, the drummer, remembered. “[He] was running the same way we were, but he was way out ahead of us.”

“He had a completely different approach in everything,” said Jay McShann, who had been among the first to recognize his talent. “Everything was completely different, just like [when] you change the furniture in the house and you come in and you won’t know your own house.”

After the arrival of Charlie Parker, the house of jazz would never be the same. His greatest innovation would be to what the late jazz historian Martin Williams called “melodic rhythm,” not the basic time but “the rhythm that the players’ accents make as they offer their melodies.” Building largely on the quarter note, Louis Armstrong had shown the world how to swing. By basing his improvisations primarily on eighth notes and developing altogether fresh methods of inflecting, ac-

centing, and pronouncing phrases, Charlie Parker showed it could be done another way. The density and harmonic sophistication of tenor-saxophonist Coleman Hawkins, the loose-limbed melodic sense of another great tenor-saxophonist, Lester Young, and even something of the supremely selfconfident phrasing of Louis Armstrong can all be heard in Parker’s playing.

No one understood his importance better than the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, who was three years older than Parker. Once, in Kansas City, while Gillespie was in Cab Calloway’s band, he had heard Parker. “He had just what we needed,” he said. “He had the line and he had the rhythm. The way he got from one note to the other and the way he played the rhythm fit what we were trying to do perfectly. We heard him and knew the music had to go his way.... He was the other half of my heartbeat.”

Parker’s genius was incontestable. So was his maddening personal complexity. A musician who’d known Parker well suggested that he should have been nicknamed Chameleon. Even in his photographs he seems to be several people all at once: now slender and boyish, now bloated and middle-aged, now youthful and lively again; sometimes wide-eyed and apparently innocent, sometimes sly and knowing, as often with a deadened gaze that seems to foretell the tragedy that eventually befell him. The scattered interviews he gave are contradictory, too. Sometimes he said that his music grew directly out of swing, at other times that it was “something entirely separate and apart from jazz.” Parker “stretched the limits of human contradiction beyond belief,” the author Ralph Ellison wrote. “He was lovable and hateful, considerate and callous; he stole from friends and benefactors and borrowed without conscience, often without repaying, and yet was generous to absurdity.... He was given to extremes of sadness and masochism, capable of the most staggering excesses and the most exacting physical discipline and assertion of will.”

Only Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington can be said to have made greater contributions to the music, and no one will ever know what further heights Parker might have reached had he not allowed his relentless hungers finally to consume him.

harles Parker Jr. was born in 1920 in I Kansas City, Kansas, and raised just across the Kaw River, in Kansas City, Missouri. His father was a tap dancer turned railroad chef, who drank too much and deserted his wife and son before the boy was 10. His mother spoiled her only child while also demanding much of him, insisting that he wear a suit and tie to school, and that he hold her hand whenever they went out together. “Charlie was always old,” Rebecca Ruffin, the highschool sweetheart who became his first wife, remembered. She did not deny his mother’s single-minded devotion to her son, Ruffin told the writer Stanley Crouch, but believed she had been more dutiful than affectionate, nonetheless. “He wasn’t loved, he was just given.... It seemed to me like he needed. He just had this need. It really touched me to my soul.”

The boy had few friends. He played alto and baritone horn in the school band, but was so often truant that he would eventually be forced to repeat his freshman year. At 13, after hearing Rudy Vallee on the radio, he talked his mother into getting him a horn like Vallee’s, only to lose interest and lend it to a friend for two years before taking up music again.

Then everything seemed to happen too fast. Barely an adolescent, he began to hang around the doorways of the bars and nightclubs that flourished just a few blocks from his home, steeping himself in the blues. By 15 he had begun his lifelong obsession with getting high. He used nutmeg at first; then Benzedrine dissolved in wine or cups of black coffee, which allowed him to play night after night without sleep; then marijuana; finally heroin. A month before turning 16, he married Rebecca Ruffin, and they soon had a son. He also began playing with a group of slightly older musicians in a local dance band called the Deans of Swing. Its trombonist, Robert Simpson, became his closest friend, and Parker was devastated when Simpson died at 21. Years later he would explain to a fellow musician that he never allowed himself to get too close to anyone, because “once in Kansas City I had a friend who I liked very much, and a sorrowful thing happened_He died.”

Parker plunged headlong into the cutting contests that were the proving ground for any Kansas City musician on the way up. He “used to come to our jam sessions,” violinist Fiddler Williams remembered. “And he kept his saxophone and instruction book in a sack. And he could play anything in the instruction book, play it backwards. But he didn’t have himself together, couldn’t run out of a major into a minor, or a diminished into an augmented chord.” One night at the Reno Club, sitting in with members of the Basie band, the 16-year-old Parker found himself in over his head, unable to make the right changes at the breakneck speed at which the older men were playing. Jo Jones hurled a cymbal at his feet to get him off the bandstand. Angry and humiliated, he got a job with a dance band in the Ozarks and spent every spare moment practicing and listening to records made by his heroes, Chu Berry and, later, Lester Young. Like Sidney Bechet and Bix Beiderbecke before him, Parker would essentially teach himself to play; unlike them, he tried to learn all there was to know about the music that had become his life. When he mastered a new tune, he would teach himself to play it in all 12 keys so that no one would ever again be able to dismiss his playing. “I lit my fire,” he remembered, “I greased my skillet, and I cooked.”

On Thanksgiving Day 1936, the car in which Parker and two other young musicians were riding to an engagement skidded on a patch of ice and overturned. One passenger was killed. Parker suffered broken ribs. He spent two months recuperating in bed, easing his pain with regular doses of morphine. His drug use evidently accelerated after he got back on his feet. He stayed away from home for weeks at a time, sold his wife’s belongings to buy drugs, pressured her to give him a divorce. “If I were free,” he told her, “I think I could become a great musician.”

In 1937 he went to work for one of his idols, altoist Buster Smith, who was a master of what was called “doubling up,” playing solos at twice the written tempo. “He always wanted me to take the first solo,” Smith said. “I guess he thought he’d learn something that way.... But after a while, anything I could make on the horn, he could make too—and make something better of it.”

No matter how intricate and fast-paced Parker’s music became, the Kansas City stomping brand of blues would remain at its heart. “What you hear when you listen to Charlie Parker,” wrote jazz historian Albert Murray, “is not a theorist dead-set on turning dance music into concert music. What you hear is a brilliant protege of Buster Smith and an admirer of Lester Young, adding a new dimension of elegance to the Kansas City drive, which is to say to the velocity of celebration.... Kansas City apprentice-become-master that he was, Charlie Parker was out to swing not less but more. Sometimes he tangled up your feet but that was when he sometimes made your insides dance as never before.”

Parker’s appearance with Jay McShann at the Savoy had not been his first visit to New York. After Buster Smith went east to help Count Basie whip his band into shape at the Famous Door in the summer of 1938, Parker followed him

to Harlem. His old mentor put him up until his wife got tired of having him around. He took a nine-dollar-a-week job washing dishes at a little club just so that he could hear another of his idols, Art Tatum, play piano every night. He sometimes ventured out to jam at Monroe’s Uptown House, but his perennially disheveled looks and the frantic pace at which he already liked to play put off a good many musicians. Some thought him a dope dealer masquerading as a musician. But one night that December, he later told an interviewer, jamming with an unremarkable guitarist named Biddy Fleet at Dan Wall’s Chili House, on Seventh Avenue between 139th and 140th Streets, he had made a personal musical discovery. Intrigued by the sophisticated chord changes of Ray Noble’s “Cherokee,” a recent hit for the Charlie Barnet Orchestra, he kept thinking there “must be something else. I could hear it sometimes, but I couldn’t play it.” Then he found he could develop a fresh melody line using the higher intervals of a chord while Fleet backed them with related changes. A few days later, a telegram from his mother telling him that his father had been stabbed to death brought him home to Kansas City before he could share his secret with anyone else, and it was more than two years before the Jay McShann band took him back to Harlem again.

The word "bebop" bothered as "jazz" had bother Duke Ellington. "Lets call it music." he said.

It was while playing with McShann that he got his distinctive nickname, Bird. When the car in which he and McShann were riding hit a stray chicken, a yardbivd, Parker insisted they pull over so that he could have it fried up by his landlady. The story got around, and the name stayed with him. “He was an interested cat in those days,” McShann said, eager to help work out riffs for the saxophone section, grateful for every chance to solo, sometimes playing a single tune backstage for hours at a time with instructions to anyone who played with him to alert him whenever he inadvertently repeated himself. “We used to have an expression when a cat’s blowing out there; the cats’d holler, ‘Reach! Reach!,’ ” McShann continued. “What we meant by that, we know that a cat knows his potential, what he can do. If you keep hitting on Bird like that, Bird would just do the impossible ... because he always had enough stored back here that he never did run out.”

Bassist Gene Ramey remembered that the McShann organization had been “the only band I’ve ever known that seemed to spend all its spare time jamming or rehearsing. We used to jam on trains and buses, and as soon as we got into town, we’d try to find somebody’s house where we could hold a session. All this was inspired by Bird.... Naturally we petted and babied him, and he traded on this love and esteem we had for him until he developed into the greatest con man in the world.” He borrowed money and failed to pay it back, nodded off on the bandstand, disappeared for days at a time.

Jay McShann was a gentle taskmaster. Like Duke Ellington, he was willing to put up with pretty much anything from his musicians, provided they turned up on time to play. But Parker constantly tested his patience. In an effort to keep dealers from getting to his alto-saxophone star, McShann left standing orders that no strangers be allowed through the stage door between sets. They got to him anyway, and after Parker collapsed from an overdose during a Detroit appearance, McShann finally, reluctantly, let him go. The bandleader Andy Kirk gave Parker a lift to New York, where he began looking for steady work. (The McShann band itself dissolved shortly afterward, when its leader was drafted.)

In late 1942 or early 1943, as American G.I.’s fought German troops for the first time in North Africa, Charlie Parker joined Dizzy Gillespie in a new big band led by Earl Hines. Since making “West End Blues” and other historic sides with Louis Arm-

strong in the late 1920s, Hines had spent most of his time in Chicago, presiding over an orchestra at the Grand Terrace ballroom, which was controlled for a time by a henchman of A1 Capone’s. But in 1940 he had bought himself out of that contract and started touring.

By 1943 his band was filled with young modernists. Besides Gillespie and Parker (who agreed to play tenor because Hines already had two altoists), it included trumpet player Benny Harris, trombonist Bennie Green, and a teenage Sarah Vaughan, hired both to sing and to share piano-playing duties with Hines; she was known as “Sailor” then for the richness of her vocabulary and her fondness for good times. The band’s big draw was a handsome baritone named Billy Eckstine, billed as “the Sepia Sinatra.”

Hines had Gillespie write arrangements of several of his own tunes for the band, including “Night in Tunisia” and “Salt Peanuts,” even though he didn’t personally much like the new sounds his young men were making. “It was getting away from the melody a lot,” he said. But he had been an innovator himself, he remembered, knew “these boys were ambitious, and [therefore] always left a field for any improvement if they wanted to do it.”

They did want to do it.

They also made it clear that they were not content to endure without complaint treatment that, after more than two decades as a black entertainer playing for white audiences, their leader had come to see as routine. When a man Billy Eckstine remembered as an “old, rotten cracker” amused himself by repeatedly throwing chicken bones into the Jim Crow car in which the members of the band were riding north through Virginia, Eckstine waited till the train reached Washington, D.C., stopped the man on the platform, demanded to know why he’d done it, and, when he didn’t answer, hit him so hard he hid beneath the train, begging for mercy. “Another thing that used to make me mad was pianos,” Eckstine recalled. “Here we come to some dance with Earl, the number one piano player in the country, and half the keys on the goddam piano won’t work. So when we’re getting ready to leave, I’d get some of the guys to stand around the piano as though we were talking, and I’d reach in and pull all the strings and all the mallets out. ‘The next time we come here,’ I’d say, ‘I’ll bet that son-of-a-bitch will have a piano for him to play on.’” “[Eckstine] used to have me so nervous!” Hines said. “I never liked to say anything, because I was always thinking that I’d come back to one of those joints and they’d think I’d done it. But those guys of mine ... they didn’t care.”

They did care about their music. Gillespie and Parker were now playing together every day. “We were together as much as we could be under the conditions that the two of us were in,” Gillespie recalled. “His crowd, the people he hung out with, were not the people I hung out with. And the guys who pushed dope would be around, but when he wasn’t with them, he was with me.” Parker had brought all his old habits to the band along with his artistry. He borrowed money constantly, missed dates, and learned to sleep onstage, wearing dark glasses, and with his cheeks puffed out, as if he were playing. According to Stanley Crouch, he also gave a pin to one of his section-mates with orders to jab him in the thigh whenever it was his turn to solo. Parker was perpetually voracious and in a hurry—“always in a panic,” as he himself said—and his ravenous appetite extended to every area of his life. The same hunger that drove him to devour drugs, alcohol, and food and to pursue women at a pace that astounded even his streetwise compatriots also allowed him to amass little-known facts on every subject from auto repair to nuclear physics and to memorize the most complicated charts after a single reading.

"We know that a cat knows his potential, what he can do,” said Jay McShann. "Bird would do the impossible."

On Valentine’s Day 1943, the Hines band appeared in Chicago at the Savoy Ballroom, the same cavernous South Side nightspot at which Artie Shaw had first heard Louis Armstrong 15 years earlier. The engagement was memorable for two reasons. Three customers were shot on the dance floor during a single set that evening. And the next day, in Room 305 of the Savoy Hotel, the band’s road manager, Bob Redcross, plugged in a portable disc recorder to capture for the first time the sound of Parker and Gillespie playing together. The bassist Oscar Pettiford had walked his instrument three miles across the city just to play with them that day, but he can barely be heard as the two musical companions tear their way through an eight-minute version of “Sweet Georgia Brown." Gillespie builds his solo with almost audible care, eacn cnorus umoiaing separately, resolving itself logically. Parker, still playing tenor rather than his customary alto, hurtles seamlessly through chorus after chorus, spilling out long ribbons of eighth notes as if they were in limitless supply. “I think I was a little more advanced, harmonically, than [Parker] was,” Gillespie later wrote. “But rhythmically, he was quite advanced, with setting up the phrase and how you got from one note to another.... Charlie Parker heard rhythms and rhythmic patterns differently, and after we started playing together, I began to play, rhythmically, more like him.” Their combined talents released so much musical energy—“fire,” one musician called it—that the other men in the band confessed they sometimes felt left behind.

It was "the height of the perfection of our music," Gillespie remembered, "on fire all the time."

But except for Bob Redcross’s homemade discs (which would not be heard beyond his circle of friends for decades), Parker’s and Gillespie’s earliest innovations went unheard on record. Earl Hines never got into a recording studio during the time they were with him. On August 1, 1942, the American Federation of Musicians had ordered its members to stop making records—other than the “V-Discs” intended only for servicemen—until the record companies agreed to pay them when their music was played in jukeboxes or on the radio. Capitol and Decca settled within a year, but Victor and Columbia held out until November 1944. And so, except for a handful of dedicated collaborators and a few devoted fans, the new music Parker and Gillespie and their cohorts were developing remained largely a secret.

n the spring of 1944, Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie found themselves playing one-nighters as part of a brand-new band led by Billy Eckstine. It was a “fantastic” band, its drummer, Art Blakey, recalled, a nurturing ground for bebop. At various times, Eckstine’s band included Sarah Vaughan, trumpeter Fats Navarro, altosaxophonist Sonny Stitt, tenor-saxophonists Budd Johnson, Gene Ammons, and Dexter Gordon, and Leo Parker on baritone. But it made only a few instrumental records, and they were “sadder than McKinley’s funeral,” according to Blakey, only a pale reflection of what the men could do in person.

By winter, Parker and Gillespie had left Eckstine and were appearing together frequently as part of a quintet at the 3 Deuces on 52nd Street in New York. “They played very, very fast,” the drummer Stan Levey said. “They had great technique, great ideas. They ran their lines through the chord change differently than anybody else.”

It was “the height of the perfection of our music,” Dizzy Gillespie remembered, “on fire all the time.... Sometimes I couldn’t tell whether I was playing or not because the notes were so close together. He was always going in the same direction as me.” Nothing quite like it had been seen or heard in more than 20 years, not since Louis Armstrong and King Oliver had seemed uncannily able to complete one another’s musical ideas when they were playing at Chicago’s Lincoln Gardens. Musically, it was a perfect partnership; personally, things were more complicated. Parker was often late and sometimes absent. When Gillespie confronted him about it, Parker denied he was using drugs. Gillespie knew he was lying. There would always be tension between them.

The next summer, Gillespie took an 18piece bebop big band on the road, touring the South as part of “Hepsations ’45,” a variety package that featured comedians, singers, and the tap-dancing Nicholas Brothers. He had thought they were to be booked into theaters, where his music— “geared for people just sitting and listening”—might have had a chance of finding an audience. Instead, he recalled, “all we were playing was dances,” and southern dancers were unmoved by “Salt Peanuts” and “Shaw ’NufF,” “Bebop” and “Night in Tunisia.” They wanted blues, and most of the young men in Gillespie’s band now considered blues a reminder of the bad old days, a legacy of Jim Crow and even Uncle Tom. “The bebop musicians wanted to show their virtuosity,” Gillespie wrote. “They’d play the twelve-bar outline of the blues but they wouldn’t blues it up like the older guys they considered unsophisticated. They busied themselves making changes, a thousand changes in one bar.”

Changes didn’t interest southern dancers. “They couldn’t dance to the music, they said,” Gillespie remembered in 1979. “But ... I could dance my ass off to it. They could’ve, too, if they had tried. Jazz should be danceable. That’s the original idea, and even when it’s too fast ... it should always be rhythmic enough to make you wanna move.... But the unreconstructed blues lovers down South ... couldn’t hear nothing else but the blues.... They wouldn’t even listen to us. After all these years, I still get mad just talking about it.”

"Nobody understood our music out on the Coast," Parker said, by which he meant fans, not musicians; "they hated it.”

On November 26, 1945, at the WOR studios in midtown Manhattan, Parker was at last scheduled to make his first recordings under his own name. He and Gillespie had appeared together on 52nd Street earlier that year, and he was now known and admired among musicians. “There was a revolution going on in New York,” one saxophone player remembered, “a rebellion against all those blue suits we had to wear in the big swing bands.” “It was a cult,” another recalled, “a brotherhood.” Soon, a third remembered, “there was everybody else and there was Charlie.”

But beyond the world of music he was still mostly unknown. At first the session seemed likely to be a debacle. Bud Powell, the pianist Parker had wanted, had disappeared. Powell’s replacement, Sadik Hakim, turned out to be unsure of the chord changes, so Dizzy Gillespie sat in at the piano on the first three tunes, “Billie’s Bounce,” “Now’s the Time,” and “Thriving on a Riff.” Curley Russell played bass, Max Roach played drums, and a 19year-old Miles Davis played trumpet on all three. But the fourth tune was “Ko Ko,” a Parker original, based on the changes of “Cherokee,” and it began with a complex, blistering introduction, which so intimidated Davis that Gillespie stood in for him, then raced back to the keyboard while Parker soloed.

“Ko Ko” would astonish those who heard it for the first time, just as the first records Louis Armstrong made under his own name had astonished people. With Max Roach boiling along in the background, Parker and Gillespie leap into their furious eight-bar unison chorus. Then each plays a dazzling eight-bar arabesque before Parker launches into two plunging, note-filled choruses that sound like nothing ever heard before on records. “‘Koko’ may seem only a fast-tempo showpiece at first,” Martin Williams wrote, “but it is not. It is a precise linear improvisation of exceptional melodic content. It is also an almost perfect example of virtuosity and economy. Following a pause, notes fall over and between this beat and that beat: breaking them asunder, robbing them of any vestige of monotony; rests fall where heavy beats once came, now ‘heavy’ beats come between beats and on weak beats.... [It] shows how basic and brilliant were Parker’s rhythmic innovations, not only how much complexity they had, but how much economy they could involve.”

Other records had hinted at what was to come, and, thanks in large part to Gillespie’s willingness to share his discoveries with anyone who asked about them, big bands like those led by Woody Herman, Boyd Raeburn, and Stan Kenton had already incorporated elements of the new music into their arrangements. But these Savoy sessions were unadulterated bebop—intricate unison themes, dissonant chords, and the most demanding kind of virtuosic solo playing, all driven by bold, assertive drumming that both helped set the ferocious pace and provided a sort of running commentary on everything the soloists were doing. Charlie Parker’s secret was out.

The singer Jon Hendricks had served in the wartime army and was on a troopship coming home from Europe when he first encountered the new music that had been developing while he was overseas. “I suddenly heard this song over the ship’s radio,” he said. “It was frenetic and exciting and fast and furious and brilliant and beautiful and I almost bumped my head jumping off my bunk. I ran up to the control room and said to the guy, ‘What was that?’ He said, ‘What?’ I said, ‘That last song you just played!’ He said, ‘I don’t know.’ I said, ‘Where is it?’ He said, ‘It’s down there on the floor.’ I looked down there on the floor, the floor’s covered in records. I said, ‘Come on, what color was the label?’ He said, ‘It’s a red label.’ Finally I found it. It was a Musicraft label and it was called ‘Salt Peanuts.’ And it was Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie. And I gave him $30 and said, ‘Play this for the next hour!’”

The war had transformed the lives and elevated the expectations of millions of African-Americans. “I spent four years in the army to free a bunch of Dutchmen and Frenchmen,” another black veteran said, “and I’m hanged if I’m going to let the Alabama version of the Germans kick me around when I get home.... I went into the army a ‘nigger’; I’m coming out a man. ” Bebop was a musical development, not a political statement. Its message was one of accomplishment, not anger. But something of the spirit of that ex-soldier— self-assured, impatient, uncompromising— would nonetheless be mirrored in the new music.

“Your music reflects the times in which you live,” Dizzy Gillespie wrote. “My music emerged from the war years ... and it reflected those times.... Fast and furious, with the chord changes going this way and that way, it might’ve looked and sounded like bedlam, but it really wasn’t.” Determined to free the music from what they considered the tyranny of popular taste, to strip it of every vestige of the minstrel past, Gillespie and Charlie Parker would try to build a brave new musical world in which talent—and only talent—would count.

In the first week of December 1945, just a few days after recording “Ko Ko,” Gillespie and Parker boarded a train for Los Angeles. Billy Berg, the proprietor of a new Hollywood nightspot, Billy Berg’s Swing Club, had invited Gillespie to bring a group west to introduce to California the kind of music that had been causing such a sensation on 52nd Street. Berg had asked for five musicians, but there were six men in the party: Gillespie and Parker, bassist Ray Brown, pianist A1 Haig, drummer Stan Levey, and vibraphonist Milt Jackson. Gillespie—who knew Parker’s habits all too well—had added Jackson to make sure that even when Parker failed to turn up, as he knew he sometimes would, there would still be five men on the bandstand, as called for in the contract.

Stan Levey had been under Parker’s spell ever since he had first played with him a year or so earlier. “Charlie Parker ... was the Pied Piper of Hamelin. I was working on 52nd Street with different people—Ben Webster, Coleman Hawkins. And this guy walks down, he’s got one blue shoe and one green shoe. Rumpled. He’s got his horn in a paper bag with rubber bands and cellophane on it, and there he is, Charlie Parker. His hair standing straight up. He was doing a Don King back then. Well, I says, ‘This guy looks terrible. Can he play? What?’ And he sat in, and within four bars I just fell in love with this guy—the music, you know. And he looked back at me, you know, with that big grin, with that gold tooth, and we were just like that. From that moment on, we were together. I would have followed him anywhere, you know? Over the cliff, wherever.”

Somewhere in the Arizona desert, the train stopped to take on water, Levey remembered, “and I look out the window and I see this spot out there carrying ... a little grip, and I’m saying, ‘What the hell is that?’ And I look closer; it’s Charles Parker.” Suffering from withdrawal and desperate for drugs, Parker had jumped down from the train and was wandering off into the empty desert in search of a fix.

Levey managed to talk Parker back aboard the train. They still had 20 hours to go. When they finally reached their destination, an admirer was at the station to warn Parker that heroin was costly and hard to come by in Los Angeles. That was only the beginning of the problems he and Gillespie and their companions faced in bringing bebop to the West Coast.

Like New York’s 52nd Street, the heart of black Los Angeles—Central Avenue between 42nd and Vernon—was home to a host of clubs: the Downbeat and Club Alabam, the Last Word and Lovejoy’s, the Memo, and Ivie’s Chicken Shack, a restaurant run by Duke Ellington’s onetime singer Ivie Anderson.

Billy Berg’s club was different. It was on North Vine Street in Hollywood, for one thing, and was meant to be a sort of California version of Manhattan’s Cafe Society, offering jazz and welcoming black as well as white patrons—something otherwise unheard of in Hollywood.

Young musicians who had been experimenting locally with the kinds of sounds Gillespie and Parker were playing turned out to hear them. Howard McGhee was there on opening night. So were bassist Charles Mingus, tenor-saxophonist Dexter Gordon, and pianist Hampton Hawes. The reed player Buddy Collette recalled Gillespie and Parker’s initial impact on him and his friends: “This was for real. The stuff that you heard on the records that you didn’t believe, you ... had to believe because you saw people standing playing it.... They were using notes that we didn’t even dare to use before because it would be considered wrong. And those stops and gos between Dizzy and Bird.... You know, you’d look at everybody and say, ‘Can you believe what we just heard?”’

A good many ordinary customers were asking one another the same question. But they seemed more “dumbfounded” than excited, Gillespie remembered. The music the young musicians loved struck many of the others in the room as frantic, nervous, chaotic. Sometimes they asked the men to sing.

Nothing could have been more insulting to musicians who wanted to be seen as serious artists, not performers, who were determined to simply play their music, not to put on a show. It was bad enough, from their point of view, that they had to share the stage every evening with Slim Gaillard and Harry “the Hipster” Gibson, musical comedians who, like Cab Calloway, specialized in novelty tunes that capitalized on the latest innercity slang for the delectation of mainstream white audiences. Gaillard drew upon a lexicon of laid-back nonsense syllables he called “vout” to produce hits such as “Flat Foot Floogie” and “Cement Mixer (Put-ti Put-ti),” while Gibson’s best-known number was called “Who Put the Benzedrine in Mrs. Murphy’s Ovaltine?” Theirs was precisely the kind of entertainment Gillespie and Parker most despised, and the two were furious when Gaillard began billing himself as “the be-bop bombshell,” fearing that their music and his comedy routines would become confused in the public mind. They were right to be afraid. When Time got around to noticing bebop that spring, it defined the new music as “hot jazz overheated, with overdone lyrics full of bawdiness, references to narcotics and doubletalk.”

Martin Williams, destined to become one of the most perceptive of all jazz historians, was still in the navy—and still in the grip of his Virginia boyhood— when he went to hear Parker and Gillespie at Billy Berg’s. Their music, he remembered, had seemed to him then not merely novel but “arrogant” and “uppity.” “What struck me even more than the music,” he recalled, “was the attitude coming off the bandstand—self-confident, aggressive. It was something I’d never seen from black musicians before.”

“Nobody understood our kind of music out on the Coast,” Parker said, by which he meant music fans, not musicians; “they hated it.” Gillespie agreed: “They thought we were playing ugly on purpose. They were so very, very, very hostile! ... Man, they used to stare at us so tough.”

"He had an incredible life force," Chan Parker recalled. "Bird was a giant. He had a maturity beyond his years.”

When Dizzy Gillespie and the rest of the sextet boarded the plane to fly back to New York on February 9, 1946, Charlie Parker was not with them. He had traded his ticket for cash with which to buy drugs. It had taken him weeks to locate a steady source of heroin: the disabled proprietor of a shoeshine stand named Emery Byrd but known to his customers as “Moose the Mooch.” Parker was so grateful to have found him that he signed over to him half his future royalties in exchange for a guaranteed supply and wrote a tune in his honor.

He worked with Howard McGhee at the Club Finale on Central Avenue. He recorded a solo on “Lady Be Good” alongside Lester Young at a “Jazz at the Philharmonic” concert that became a standard in the repertoire of aspiring saxophonists all over the country. And he recorded for a new label called Dial several of his own tunes, including “Yardbird Suite” and “Ornithology.”

Then, in April, the police arrested Moose the Mooch. He was sent to San Quentin, and Parker was once again without heroin. To compensate, he began drinking as much as a quart of whiskey a day. Soon he was living in a converted, unheated garage, with only his overcoat for bedding.

Howard McGhee found him there and arranged for him to record again for Dial on July 29. But Parker arrived so drunk that the record producer had to help hold him up in front of the microphone. A psychiatrist gave Parker six tablets of phenobarbital to bring him around, and he managed to stumble through a troubled take of “Lover Man.” That night Parker twice wandered into the lobby of his hotel wearing only his socks, then fell asleep while smoking and set his bed ablaze. The firemen had to shake him violently to wake him, and when he protested, the police hit him with a blackjack and put him in handcuffs. He spent 10 days in jail, charged with indecent exposure, resisting arrest, and suspected arson, and was then transferred to Camarillo State Hospital. He would spend six months inside its walls, tending a lettuce patch, putting on weight, playing C-melody saxophone on Saturday nights in the hospital band. His third wife, Doris Sydnor, who had met him—after his short, failed second marriage—when he was playing the Famous Door, where she was the hatcheck girl, went to California and took a job as a waitress so that she could visit him three times a week. Eventually, he would write a tune about his new home: “Relaxin’ at Camarillo.”

Most critics remained wary of the new music Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were making, and the strict traditionalists among them, who had already pronounced swing inauthentic, found bebop still harder to swallow. The Jazz Record charged Gillespie with seeking to “pervert or suppress or emasculate jazz.” Outnumbered, the youthful champions of modernism, in turn, denounced the opposition as “Moldy Figs.” The argument was conducted mostly on the periphery of the music. Ben Webster and Don Byas and other giants of the swing era sought out beboppers with whom to play. Coleman Hawkins recorded with Gillespie and Parker, worked with Howard McGhee, and included Thelonious Monk in one of his groups even when club owners wanted him replaced.

But there were musicians to whom bebop really did seem little more than noise. When McGhee shared a bill with the New Orleans trombonist Kid Ory in Los Angeles, Ory stormed out after one set, saying, “I will not play with this kind of music.” “We don’t flat our fifths,” said Eddie Condon, “we drink ’em.” Tommy Dorsey denounced Parker and Gillespie as “musical Communists.”

The embattled boppers gave as good as they got. Gil Fuller, who had arranged for Gillespie’s big band, said comparing what had gone before with the music he and his associates produced was like equating a “horse and buggy with a jet plane.” Gillespie himself once likened earlier jazz to “Mother Goose rhymes. It was all right for its time, but it was a childish time.” And the “progressive” bandleader Stan Kenton charged that the trouble with Louis Armstrong and the other members of his generation was that they played without what he called “science.”

"Jazz has got to go on from here" Parker told trumpeter Red Rodney. "We just can't stop with thi&"

Duke Ellington believed that the impact of his own work had been lessened by its having been categorized as “jazz,” and he warned Gillespie not to let his music be limited by anyone else’s label. But in his eagerness to win a big following and keep his band together, the younger man paid no attention. “If you’ve got enough money to play for yourself,” he said, “you can play anything you want to. But if you want to make a living at music, you’ve got to sell it.” Nobody ever worked harder to sell his music than Gillespie did. He was a dervish onstage, hurtling through breakneck solos in the highest register, then jitterbugging, singing, swapping jokes with comedians, wearing funny hats. “Comedy is important,” he explained many years later. “As a performer, when you’re trying to establish audience control, the best thing is to make them laugh if you can.... Sometimes, when you’re laying on something over their heads, they’ll go along with it if they’re relaxed.” Gillespie did so much to make them laugh during one concert at Carnegie Hall that Louis Armstrong came back-

stage afterward to tell him he was overdoing it. “You’re cutting the fool up there, boy. Showing your ass.”

For better or worse, Gillespie allowed himself to become the public face of bebop. The William Morris agency billed him as the “Merry Mad Genius of Music” and encouraged the press to write colorful stories about his dark-rimmed glasses and goatee, his berets, the leopardskin jackets he sometimes wore onstage, the cheeks that puffed alarmingly when he played, and, later, the distinctive upthrust bell of his trumpet, which he said helped him hear himself better—everything except his music.

When Charlie Parker returned to music after his long stay at Camarillo, he was not pleased by the kind of attention Dizzy Gillespie had been getting—or by the eagerness with which Gillespie had seemed to seek it. Parker had brought bebop with him from Kansas City in 1942, he assured one interviewer, implying that no one else had had a hand in its creation. Gillespie’s big band was a bad idea, he told another, because it was forcing his old partner to stagnate: “He isn’t repeating notes yet, but he is repeating patterns.” Parker was even more unhappy with the cultish aura that now surround-

ed the music. “Some guys said, ‘Here’s bop.’ Wham!” he told another interviewer, shaking his head sadly. “They said, ‘Here’s something we can make money on.’ Wham! ‘Here’s a comedian.’ Wham! ‘Here’s a guy who talks funny talk.’” The word “bebop” bothered him, precisely as “jazz” had bothered Duke Ellington. “Let’s call it music,” he said.

Parker formed what came to be called his classic quintet, with Max Roach on drums, Tommy Potter on bass, Duke Jordan on piano, and a still-youthful Miles Davis on trumpet. (Later, Davis would be replaced by Kenny Dorham, A1 Haig would substitute for Jordan, and Roy Haynes would replace Roach.) Parker played with more assurance and clarity than ever, but he remained perpetually unsatisfied. He was also embarrassed by the acolytes who followed him from bandstand to bandstand, carrying disc recorders, which they turned on whenever he stepped forward to solo and clicked off again the moment he had finished.

In May 1949, a delegation of American musicians landed in Paris for one of the first international jazz festivals ever held anywhere. The New Orleans sopranosaxophone star Sidney Bechet was the best known to French fans, but Charlie Parker had been invited as well. There continued to be dark murmurings in the jazz press that traditional and bebop musicians were mortal enemies. Bechet had told an interviewer that bebop was already “as dead as Abraham Lincoln,” and he and Parker had only recently been pitted against each other in a broadcast “Battle of Music,” advertised as a “showdown” by its organizer, the writer Rudi Blesh. In fact, they got along fine, once Bechet had figured out how to open the dressingroom window to let out Parker’s marijuana smoke. Not given to compliments, he nevertheless told Parker how much he admired “those phrases you make,” and in the jam session that ended the final day of the festival these two masters—the white-haired jazz pioneer and the 29year-old architect of bebop—found instant common ground in the blues, the music that was at the heart of everything either man ever played.

To his surprise and pleasure, Charlie Parker found himself a hero to the French, hailed as a worthy successor to Bechet, Armstrong, and Ellington, sought out by Jean-Paul Sartre and other intellectuals, and treated for the first time in his life not as a performer but as an artist. He had already begun to talk of broadening his horizons still further, but when he got back to New York and tried to interest the producer Norman Granz in commissioning works for him to record with a 40-piece orchestra, Granz instead hired dance-band arrangers to produce lush settings for popular standards. The result— an album called Charlie Parker with Strings—was disliked by most critics, who found the arrangements bland and unimaginative and accused Parker of selling out, precisely as they’d once scolded Louis Armstrong for abandoning his New Orleans repertoire in favor of popular songs. They failed to see that, as Parker himself said, a performance should be judged “good or bad not because of the kind of music—but because of the quality of the musician.” Parker’s long, hardedged, bluesy lines unfurled beautifully above the strings, and on “Just Friends”— the best-selling of all his recordings—he produced one of the most haunting improvisations of his career. Of all his records, he said, it was the only one he ever really liked.

Offstage, Parker was often out of control. "This is my home," he told a friend as he rolled up his sleeve to inject himself.

In December, two weeks after Parker made his first recordings with strings, the refurbished Clique club on Broadway, renamed Birdland in his honor, opened its bright-red doors for the first time. The opening bill was a smorgasbord of stylists: Max Kaminsky and Hot Lips Page, as well as Lester Young, Charlie Parker, and a little-known singer named Harry Belafonte. “Feelings between the boppers and the traditional jazzmen were strained, to put it gently,” Kaminsky wrote. Some of the younger musicians had been openly disrespectful of Page, and Page had been wounded by their derision. “But Charlie Parker,” Kaminsky said, “who was rated the great genius of all that music, liked my band better than anything else he heard there. We had nothing else in common; I couldn’t drink the way he did and I didn’t know his friends and never went out with him on any parties, but musically we became good friends.”

Nothing musical was ever alien to Charlie Parker. He often drank at a midtown bar whose jukebox was stocked in part with country music. When one of his acolytes asked why he liked to hear songs they all thought corny, he answered, “Listen. Listen to the stories.” A friend remembered leaving him transfixed in a Manhattan snowstorm late one night, unable to tear himself away from the thump and blare of a Salvation Army band. Another told of driving with him through the countryside when someone remarked idly that livestock loved music. Parker asked the driver to stop, assembled his horn, stalked into a field, and gravely played several choruses to a bewildered cow.

“Jazz has got to go on from here,” he had told trumpet player Red Rodney. “We just can’t stop with this.” And when Rodney asked him who would show the way, he answered, “I’d like to be the one to do that.” Like Bix Beiderbecke before him, he began to look to European composers, not American sources, for inspiration. The future, he told one interviewer, lay in finding a way to blend the complex harmonies of modem European music with the emotional color and dynamics of jazz. But, also like Beiderbecke, he knew he lacked the grounding in music theory that would have allowed him to bring about the kind of meeting of musical traditions he had in mind. To rectify that, he sometimes spoke wistfully of returning to France to study composition with Nadia Boulanger, enrolling at the Conservatoire Americain de Fontainebleau, or taking instruction in orchestration from Edgard Varese. “I only write in one voice,” Varese said Parker told him. “I want to have structure. I want to write orchestra scores.”

Parker seemed finally to have found a little domestic peace. His marriage to Doris Sydnor had ended, but he had moved in with a woman named Chan Richardson and adopted her daughter. “He was irresistible,” Richardson remembered. “He had a life force, an incredible life force. Bird was a giant_He had a maturity beyond his years. In fact, he said to me one day, ‘I’m not one of those boys you’re used to.’” They would have two children together, Pree and Baird, and would live for a time on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, where Parker led a life that on the surface seemed very like that of his neighbors: breakfasting with the children, strolling to the comer for the morning paper, watching Westerns on television.

But with Charlie Parker, nothing was ever quite as it seemed. On the bandstand, he was usually able to discipline his furious talent. But offstage he was all too often out of control. “ This is my home,” he told a friend as he rolled up his sleeve to inject himself. The pianist Hampton Hawes remembered watching in disbelief one evening as Parker, chain-smoking marijuana, first downed 11 shots of whiskey and a handful of Benzedrine capsules, then shot up: “He sweated like a horse for five minutes, got up, put on his suit, and half an hour later was on the stand playing strong and beautiful.”

There would still be nights when he’d pull himself together to play strongly and beautifully, but they would grow fewer and farther between as the years went by, and the appetites that always gnawed at him would prevent him from seriously following any of the new musical paths of which he’d spoken, precisely as similar hungers had kept Beiderbecke from following his. “He tried to kick many times while he was with me,” Chan Parker recalled, “sometimes very successfully. But he told me once, ‘You know, you can get it out of your body, but you can’t get it out of your brain.’”

Dizzy Gillespie’s band had fallen on hard times as well. For all his success, his payroll continued to outpace profits. Music-lovers clustered around the bandstand wherever he appeared, but the big crowds of dancers the band needed to stay afloat stubbornly failed to materialize. During one southern tour, even the sight of Gillespie and guest star Ella Fitzgerald doing the lindy together had not been enough to persuade other dancers to join in. "They didn't care whether we played a flatted fifth or a rup tured 129th,” Gillespie wrote. “They’d just stand around the bandstand and gawk.”

Parker seemed suspicious even of his admirers. "They just came out to see the world's most famous junkie," he said.

Finally, in March 1950, Lorraine Gillespie gave her husband an ultimatum: “You got a hundred musicians or me! Make up your mind.” Gillespie reluctantly let all of his men go. “Everybody was sorry about that, man,” he said many years later. “Cats were crying_So was I. The fad was finished.”

On February 24, 1952, Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker appeared together on a television variety show called Stage Entrance. The kinescope made that day is all that we have of Parker in public performance, and the Down Beat awards ceremony that precedes it provides an excruciating example of the kind of condescension often displayed toward jazz and jazz musicians, even by those who believed themselves boosters. The critic and composer Leonard Feather delivers a stiff little speech about brotherhood, then hands the host, Broadway gossip columnist Earl Wilson, a pair of wooden plaques to present to Parker and Gillespie. Wilson greets the musicians, offers up the plaques—making fun of Gillespie’s nickname as he does so—and then asks, “You boys got anything more to say?”

For once, Gillespie is speechless. Parker, his face without expression, his voice low and icily polite, replies: “They say music speaks louder than words, so we’d rather voice our opinion that way.” During that voicing—an abbreviated version of the bop anthem “Hot House”—Parker’s face remains impassive, his fierce eyes and the movement of his big fingers on the keys the only outward signs of the effort required to yield such brilliant, jagged cascades of sound, the sound itself the most eloquent possible response to patronization.

The end of the Gillespie big band had been more than a personal disappointment for its leader. It also marked the end of an honorable but doomed effort to build a bridge between the new music and the old jazz audience. Similar efforts by other musicians would be made over the years to come. None would entirely succeed. For better or worse, jazz seemed on its way to becoming an art music, meant for concert halls and nightclubs, not ballrooms—adventurous and demanding; intended for aficionados, not ordinary people; infused with the every-musician-for-himself spirit of the jam session; aligned not with the American mainstream but with the growing counterculture for which commercial success was evidence of corruption, of “selling out.” “Our dislikes followed a pattern,” the jazz writer Barry Ulanov once confessed, “which began with our celebration of an unknown musician, singer, or band, and ended with our derogation of the same musician, singer, or band when he, she, or they had achieved popularity.”

There was more to it than that. Jazz had started out as an exuberant ensemble form, its impact derived in large part from the cooperative spirit of the musicians, their ability simultaneously to play and to listen to one another. A man’s reputation then had rested on his individual sound and the imagination and rhythmic sophistication he brought to the twoand four-bar breaks that Jelly Roll Morton said were essential to the music. In the early 1920s the singular genius of Louis Armstrong had brought the soloist front and center and established once and for all the notion of the improvising jazz musician as romantic hero. But until the early 1940s even the most celebrated soloists had still been expected to work their magic within a carefully arranged framework. Solos remained relatively brief. A premium was put on telling one’s story with economy as well as with emotion and imagination. And the theme on which the improvisation was based was often as familiar to the listener as it was to the musicians.

The music that Parker and Gillespie pioneered was deliberately different. Tunes were either wholly new or consciously disguised. Ensemble passages were almost beside the point. Everything depended on the energy and ideas of the improvisers. If that energy and those ideas seemed inexhaustible—as they routinely did when bebop’s creators were on the bandstand—the sheer momentum and creative power let loose had the potential to thrill anyone willing to listen. But even when Parker and Gillespie were playing, there was always the risk that, by pouring forth so much unrelenting musical complexity, they would eventually inundate even their admirers. (Parker himself understood this. “More than four choruses,” he once warned Milt Jackson, “and you’re just practicing.”) And over a long evening, in the hands of less talented musicians, the standard bebop format-ensemble theme, string of solos, ensemble theme—could exhaust the patience of even the most earnest audience.

On the night of October 30, 1954, Charlie Parker appeared at New York’s Town Hall. Thelonious Monk was on the bill that evening. So were several of the most promising of Parker’s young admirers: tenor-saxophonist Sonny Rollins, trumpet player Art Farmer, pianist Horace Silver. But the publicity for the evening had been poor, more seats were empty than filled, and at intermission the musicians’ union seized half of Parker’s earnings as a penalty for having failed to follow its rules. Several weeks later, the record producer Ross Russell went to see Parker play at a 54th Street spot called Le Downbeat. Parker’s suit was dirty and unpressed, Russell said, and he was wearing carpet slippers instead of shoes: “His face was bloated and his eyelids so heavy that only half the pupils showed. The first five minutes of the set were spent in slowly assembling his saxophone while fellow musicians, all of them unknown, stood nervously on the bandstand. When Charlie got around to playing, it was evident that he was having trouble getting air through the horn.”

Parker was clearly spiraling downward. In March he had been in Hollywood when he received word from Chan in New York that their two-year-old daughter, Pree, was dead of pneumonia. He managed to get through the funeral, but then seemed unable to hold himself together. An engagement with a string section at Birdland ended in disaster when he drank too much and tried to fire the band. The manager fired him instead. He went home to Chan, quarreled with her, and tried to kill himself by swallowing iodine. Ambulance workers saved him. He twice had himself committed to Bellevue Hospital for psychiatric help, began riding the subways all night, often seemed frightened, suspicious even of his admirers. “They just came out... to see the world’s most famous junkie,” he told a friend.

The man who had hoped to demonstrate that jazz need not be linked to show business had himself become a public spectacle. “No jazzman,” wrote Ralph Ellison, “struggled harder to escape the entertainer’s role than Charlie Parker. The pathos of his life lies in the ironic reversal through which his struggles to escape what in Armstrong is basically a make-believe role of clown—which the irreverent poetry and triumphant sound of his trumpet makes even the squarest of squares aware of—resulted in Parker’s becoming something far more ‘primitive’: a sacrificial figure whose struggles against personal chaos, onstage and off, served as entertainment for a ravenous, sensation-starved, culturally disoriented public which had only the slightest notion of its real significance.”

Soon, as one saxophone player remembered, “there was everybody else and there was Charlie."

One evening, Parker made his way into a club where Dizzy Gillespie sat listening to a band. Parker was disoriented: “Diz, why don’t you save me?” he said over and over again. “Why don’t you save me?” “I didn’t know what to do,” Gillespie remembered. “I didn’t know what to say.” Parker stumbled back out onto the street.

“I ran into him one night about three in the morning,” the writer Nat Hentoff recalled. “I was going downstairs into Birdland. Bird was coming up. We didn’t [really] know each other. I’d interviewed him a couple of times on radio. And tears were streaming down his face. He said, ‘I’ve got to talk to you, I’ve got to talk to you.’ I said, ‘Fine, there’s an all-night coffee shop on the comer.’ ‘No, no. I’ll call you tomorrow.’ Well, he never called. I could have been anybody, I think.”

On Saturday, March 5, 1955, Parker was booked into Birdland again, this time as leader of a quintet that included Art Blakey, the trumpet player Kenny Dorham, bassist Charles Mingus, and the troubled pianist Bud Powell. Parker arrived late, then fled the bandstand when he saw that Powell was so drunk he could barely stay on the piano bench. When Parker came back for the second set and called the first tune, Powell insisted on playing another, then slammed the keyboard shut and walked off while Parker stood at the microphone helplessly calling after him, “Bud Powell,” “Bud Powell,” over and over again. Finally Mingus pushed him aside. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he told the crowd, “please don’t associate me with any of this. This is not jazz. These are sick people.”

On the evening of March 9, George Wein, the owner of a Boston club called Storyville, was expecting Parker to turn up for an engagement that was to begin the following day. “I came into the club about eight o’clock,” he recalled, “and Bird was not there. And somebody said, ‘Bird’s on the telephone.’ And I picked up the phone and I dialed the number and a recorded voice said there was a yellow-tipped swallow seen this morning at the Ipswich marshes. It was the Audubon Society. Somebody played a joke on me, you know, to call ‘Bird.’ ... And I hung up. I laughed. And Bird never showed up. So far as we were concerned, ‘what the hell, Bird goofed again.’ But it was his last goof.”

Parker had packed his bag that evening, intending to leave New York for Boston. But on the way to the train station he dropped by the Stanhope Hotel on upper Fifth Avenue to see his friend the Baroness Pannonica de Koenigswarter, a member of the Rothschild family and a generous patron of jazz and jazz musicians. Parker was clearly ill when he got there, and soon began vomiting blood.

Alarmed, the baroness called a doctor. The doctor asked Parker if he drank. “Sometimes,” Parker answered, “a sherry before dinner.” The doctor urged that he be hospitalized. Parker refused. He’d had enough of hospitals. The baroness and her daughter agreed to do what they could for him.

On Saturday evening, March 12, still at the Stanhope, Parker turned on the television to watch Stage Show, the Dorsey brothers’ weekly variety program. He had always liked the sound of Jimmy Dorsey’s saxophone. The first act was a comedy juggler. Parker laughed, choked, then collapsed. By the time the doctor could get there, he was dead. The official cause was pneumonia, complicated by cirrhosis of the liver. But Parker had simply worn himself out.

Although the attending physician estimated Parker had been in his early 60s, he was just 34 when he died. By the time he was buried in Kansas City, admirers had already covered walls in Greenwich Village with the slogan BIRD LIVES.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now