Sign In to Your Account

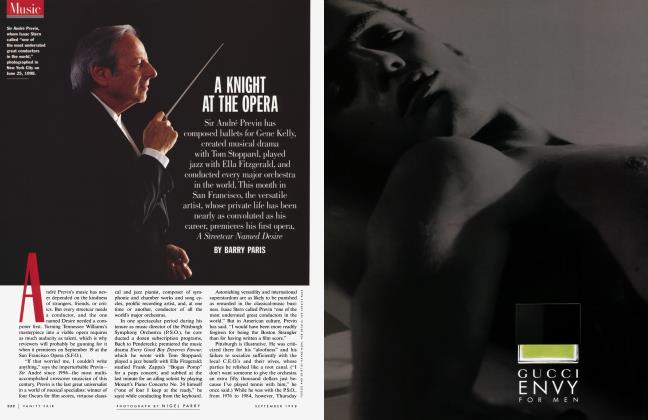

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

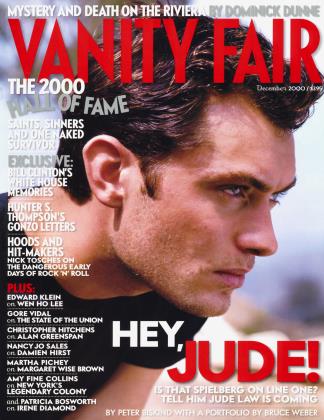

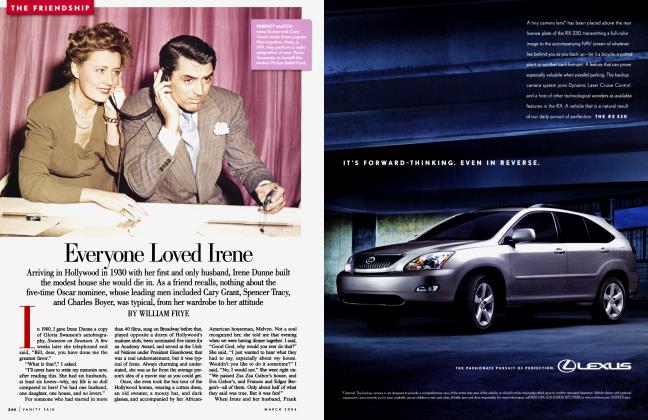

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowBUNNY DEAREST

New, long-lost stories by Margaret Wise Brown, author of such beloved children's books as The Runaway Bunny and Goodnight Moon, are being published half a century after her freakish death at 42. Childless and unsentimental, Brown may have captivated generations of kids precisely because of her own traumatic youth

MARTHA PICHEY

BOOKS

On a January day in Vermont in 1991, a cedar-lined trunk stored in the loft of a barn for nearly 40 years was opened. When literary agent Amy Gary looked inside, she knew her hunch had been right: a writer as prolific as Margaret Wise Brown, worldbeloved author of Goodnight Moon and The Runaway Bunny, had left behind a treasure store of poems, songs, and stories. "I had the windows wide open; the smell from those old onionskin papers was terrible," recalls Gary, who represents Brown's estate. "I remember reading a particularly good manuscript, and being too exuberant to cry, I merely stood at the window, breathing in the very cold air. I made copies of everything, terrified at the thought that they should be lost again."

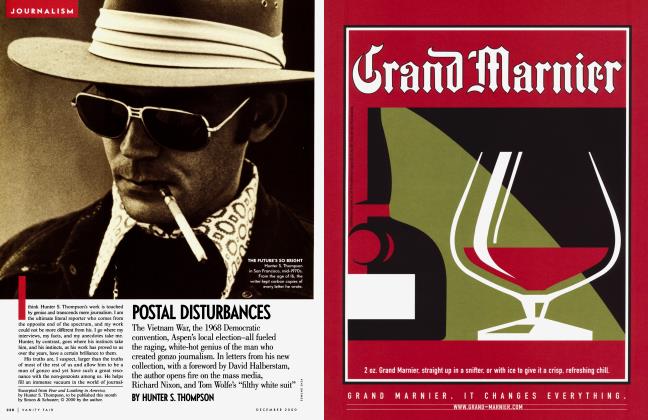

This year those manuscripts are still making their way to readers, with such winsome titles as Mouse of My Heart and, in time for Christmas, A Child Is Born. Nearly 50 years after Brown's death, new rooms in her unique imagination are opening on the page, beckoning a fresh generation of children—and their parents—into her dreamlike world. Like Goodnight Moon, one of the best-selling children's books of all time (with almost 11 million copies sold since 1947), the new stories suggest an author deeply attuned to her readers' desires and anxieties. And so perhaps it should come as no surprise that Brown felt those emotions keenly herself.

In fact, though she appreciated her gift, Brown felt trapped within her own childhood's traumas, as if she were embedded in amber. She longed to feel grown-up, to write for adult readers, and to have a stable, mature relationship. For years she felt she'd found a mentor in a poet and actress who was 20 years older than she. But the woman who called herself Michael Strange was more of a demanding parent than a loving partner, and Brown struggled throughout the 1940s to find a tranquil place in Strange's sophisticated world. Free at last of Strange's hold, Brown happened to meet, and fall deeply in love with, James Stillman Rockefeller Jr., a great-grandson of the first chairman of Citibank.

Brown finally seemed fated for happiness—until a freak accident on a prehoneymoon trip to Europe killed her suddenly at the age of 42. To the friends who gathered to mourn her, "Brownie" was a tragic Figure after all, despite the more than 100 books she'd written. They were left to wonder why it had taken her so long to Find happiness. And what sad secrets had kept her from having children of her own.

A beautiful, athletic, green-eyed blonde, Brown called herself the Bunny and sometimes the Bunny No Good. Part Holly Golightly, part Alice in Wonderland, she drank in Manhattan like a vital potion, using its sights and sounds to shape her first books. In the late 1930s, her Greenwich Village apartment was home to a cat named Sneakers, a dog named Smoke, a flying squirrel, and a visiting goat. She persuaded the local grocer to teach her how to play a horn. When her first royalty check arrived, she blew it on a cartload of flowers and threw an impromptu party.

"She was almost overwhelmingly original," says New Yorker writer Naomi Bliven. "Never for a moment did you feel she was lackadaisical about anything. " Her creative spirit delighted, and occasionally maddened, all who knew her. "For 10 minutes I was enchanted by what she had to say," remembers Bliven's husband, Bruce, "and by the 11th minute I had the need to run away."

She was profiled in Life as "Child's Best Seller" by Bliven, himself a New Yorker staff* writer. "Her striking appearance," he wrote, "is usually punctuated by some startling accessory such as a live kitten in a wicker basket ... and is emphasized nearly always by a high-spirited Kerry blue terrier on a kelly green leash."

Pets were Brown's family, in part because her parents had had a loveless marriage and presided over an arid home, first in Brooklyn, then in Beechurst, Long Island. "I had thirty-six rabbits," she wrote in her Junior Book of Authors entry (1951),

"two squirrels—one bit me and dropped dead—a collie dog, two Peruvian guinea pigs, a Belgian hare, and seven fish and a wild robin who came back every spring."

She found refuge in the woods and on the beaches of Long Island. Her imagination was nourished by the sight of an apple, the sound of a gull, the touch of a rabbit's fur. "The important thing about the sky,"

Brown wrote in The Important Book (Harper & Brothers, 1949), "is that it is always there.

It is true that it is blue, and high, and full of clouds, and made of air. But the important thing about the sky is that it is always there."

After graduating from her mother's alma mater of Hollins College in Virginia, she moved to Manhattan and rarely visited her family, though she remained close to her younger sister, Roberta. (None of the three siblings had any children.) Gratz, the only son, went to M.I.T., and Roberta went to Vassar, where she later returned to teach physics. In the midst of their success, Margaret was floundering. "I feel like a green vegetable—peas—that am't [s/'c] cooked yet but are doing a lot of whirling about in the kettle," she wrote to her favorite college professor.

To engage the five senses, Brown wanted "books for little children in fur and peachskin with glass buttons sewed on and hot and cold pages."

In 1935, while casting about for a serious career, she tutored a 12-year-old girl named Dorothy WagstafF, who was too ill to attend school that year. "I told her I needed to learn math," remembers Wagstaff, whose married name is Ripley, "but Goldie said she didn't know any math, and that we should go to the natural-history museum instead. So we went to all the museums and had a wonderful time."

hen Brown herself became a student again, first at Columbia in a fiction workshop (which she quit, claiming she wasn't good at thinking up any plots) and then at the Bureau of Educational Experiments' Cooperative School for Teachers. Nicknamed Bank Street for its location in Greenwich Milage, it was the nation's most progressive teacher-training college. Had it not been for the Writers Laboratory, she might have given up there too: Brown had neither the desire nor the temperament to teach young children. Her attitude certainly didn't square with the conventional image of a children's writer. "I treat them like little animals," she told a reporter from the Brooklyn Eagle. "I'm not nice to them like other people.... I admire their absolute integrity, their dignity, their strength and individuality. But I am not going to become maudlin about them just because they're little."

What inspired her was children's use of language. She recorded it constantly, and her young pupils' expressions found their way into stories she submitted to the Writers Laboratory. "The meetings when 'Brownie' read a new story were delightful, often hilarious, occasions for the rest of us," wrote fellow student Edith Thacher years later. "We may also have experienced some private despair at her prodigious output."

By 1940, Brown had published 14 books, as well as begun working as both editor and in-house writer for William R. Scott, who started his publishing venture in a closet at Bank Street. ("I came for lunch and stayed for four years" was how Brown summed it up.) The first of her 29 titles for the seminal Young Scott Books was Bumble Bugs and Elephants: A Big and Little Book. Brown persuaded an unknown artist named Clement Hurd to have a go at illustrating the text, and his bright graphic style dovetailed perfectly with Scott's fresh approach.

"That ancient book world was populated with giant women," said the artist-writer Maurice Sendak in the Horn Book, "grand, inspired, towering women who invented the American children's book from scratch. Back then, most publishing-type guys wouldn't be caught dead in a 'kiddie-book' department." Ursula Nordstrom, one of the tallest of those "towering" women, was working at Harper & Brothers in 1937, when the company published Brown's first book, When the Wind Blew. She headed the children's division for 33 years and was fierce in her determination to publish "good books for bad children." Nordstrom and Brown had a deep respect and affection for each other, laced with a wry humor. The editor began her letters "Dear Genius," and Brown replied to "Ursula Maelstrom."

But an exclusive working relationship it wasn't, for Brown was negotiating contracts with six publishing houses and employing three pseudonyms. She was insisting on an unprecedented 50-50 royalty split with illustrators, instead of a flat fee without royalties for the artist. A generous talent (she had her sister illustrate The Fish with the Deep Sea Smile because she knew Roberta needed the money), she collaborated with outstanding illustrators—H. A. Rey (best known, with wife Margret, for the Curious George series), Crockett Johnson (.Harold and the Purple Crayon), Kurt Wiese (The Story About Ping), Garth Williams (Stuart Little), Esphyr Slobodkina (Caps for Sale), and, most important, Clement Hurd.

She grasped instinctively how important it was to engage the five senses, and she wanted "books for little children in fur and peachskin with glass buttons sewed on and hot and cold pages." Her "smell book" went unfinished, but she made notes to "smell the cabbage, smell the lemons, smell the baby's toes." Far-fetched rather than farsighted were an idea for Humpty Dumpty's ghost to rise from his eggshell body and another for a story called "The Baby." On a scrap of paper tucked into her diary she'd written, "The flies were trying to eat him, because they knew he was full of cake."

Brown's intense affair with Michael Strange began in the early 1940s, and they probably met at the Grade Square apartment Strange shared with her third husband, Harrison Tweed. Strange was a glamorous figure—she'd been married to John Barrymore—and conversation would come to a halt when she entered a room. She clearly bewitched Brown.

By the time they met, Strange (born Blanche Oelrichs in Newport, Rhode Island) had transformed herself from socialite to socialist, traveling around the States to give readings from the Bible and the Communist Manifesto, with her own poems sandwiched in between.

"I am a quiet, humble-minded person who writes plays and poetry and occasionally likes to take a small part on the stage," Strange once said, a bit disingenuously. She had already published four volumes of poetry and a play, Claire de Lune (Barrymore and his sister, Ethel, had starring roles), and charmed a besotted Maxwell Perkins into editing her autobiography, Who Tells Me True, at Scribner's in 1940. Brown felt little sense of achievement by comparison.

At the end of 1943, Brown and Strange were living in apartments across the hall from each other on East End Avenue. Strange called Brown the Bun and Golden Bunny No Good. Brown's names for Strange included Sir Baby and My Only Rabbit. They shared a passion for literature-poetry in particular—and also for dramatic scenes, which drove Brown to despair, as her diary entries reveal:

January 5, 1948. Half the time you don't act like Michael. And your cruelty bewilders me utterly.

January 6. Terrible sleepless night. I miss you too much. Feel ill from this division. January 8. Didn't see you. Heard you through the door and whistled. Old Rabbit, this all seems like a silly game.

At best, Brown looked to Strange as a dynamic guide who would lead her out of the world of children's books and into the world of literary heavyweights. At worst, Brown was on the receiving end of explosive tirades from a disturbed woman whose life was marred by three divorces and the death of her middle child.

Strange was married to Barrymore throughout the 1920s. Their only child, Diana, wrote in her memoir, Too Much, Too Soon, "Instinctively I sought affection from my mother, but she was too imperious, too remote. She carried herself like a little general, her back rigid, her chin up, her dark eyes flashing.... I could only introduce her as 'My Mother, Miss Strange'—never as just 'Mother.'" Though the 1957 autobiography ends on a hopeful note, Diana Barrymore died of alcohol and barbiturates three years later.

Initially called "Goodnight Room," the story included the closing lines "Goodnight cucumber/ Goodnight fly."

In the midst of polishing manuscripts such as A Child's Good Night Book and Willie's Walk to Grandmama, Brown was a witness to disturbing episodes in the life of Michael Strange. In 1944, Strange's son Robin (from her first marriage) was mourning the death of a lover who had thrown himself off the Empire State Building. Robin died of a fatal dose of alcohol and pills, and Strange moved his furniture into her Connecticut country home. "She took Robin's bed into her bedroom and placed hers in his," wrote Diana Barrymore. "And for the rest of her life she slept in Robin's bed." Repeatedly, Brown became the target for Strange's unresolved anger and guilt.

Brown had a safety valve of sorts—she was in psychoanalysis throughout the 40s, despite Strange's harsh disapproval. "I would leave the Psychoanalyst even," she wrote to Strange, "but I can't say I am cured of the reason I went to him any more than you can say that your blood is cured of its distress." (Strange had been diagnosed with leukemia.) "It is for God to judge and not you or me where in an attempt to change one goes for help."

s best I can remember, my parents hated Michael Strange, and knew how destructive she was for Brownie. As did most of her friends," says illustrator Clement Hurd's son, Thacher. Some people were made uncomfortable by the sexual implications of this intense "friendship." When I asked friends still living whether Brown and Strange slept together, they either sidestepped the question by saying it didn't matter or insisted that they didn't. Bruce Bliven alone was forthright: "Oh, of course they did," he muttered.

Clement Hurd married Edith Thacher, Brown's Bank Street friend, and she too collaborated with Brown, sharing authorship on six titles. (For these, Brown used the pseudonym Juniper Sage.) "I love my parents' description of Brownie arriving at their house in Vermont in a big convertible, all wrapped in fur with her dog in back," says Thacher Hurd, who is also a children's author and co-founder of the Peaceable Kingdom Press in Berkeley, California. He remembers "the three of them working passionately for three days, and then my parents collapsing in complete exhaustion after she left."

Brown and Hurd teamed up for a second time with The Runaway Bunny, in 1942. The hide-and-seek tale of a mother rabbit and her baby bunny was based on a medieval Provencal ballad. (Brown had spent two years at a Swiss boarding school, and her French was excellent.) The original included the lines:

"If you pursue me I shall become a fish in the water and I shall escape you."

"If you become a fish I shall become an eel."

"If you become an eel I shall become a fox and I shall escape you."

Brown's fresh interpretation, which has since sold four million copies, gave readers "a little bunny who wanted to run away."

"If you run after me," said the little bunny, "I will become a fish in a trout stream and I will swim away from you."

"If you become a fish in a trout stream," said his mother, "I will become a fisherman and I will fish for you."

Michael Strange called Brown the Bun and Golden Bunny No Good. Brown's names for Strange included Sir Baby and My Only Rabbit.

"She scrawled the first lines of that book on the back of her lift ticket at Mohawk Mountain in Connecticut," says Dorothy Ripley, whom Brown often visited in nearby Litchfield, and who chose Brown to be godmother to her first daughter, Laurel. "If you become ... I will become" is the book's gentle, reassuring refrain. "'Shucks,'" says the little bunny, finally exhausting his desire to change, "'I might just as well stay where I am and be your little bunny.' And so he did." Brown sent the finished manuscript to Nordstrom in the spring of 1941. Her editor loved it—except for the ending—and she urged Brown to finish The Runaway Bunny less abruptly. Early that summer, Brown made a simple addition that summed up the gentle current of love and humor throughout the book. She sent the following telegram to Nordstrom in New York: "HAVE A CARROT," SAID THE MOTHER BUNNY.

Rabbits—sensually soft and inherently vulnerable to bigger creatures in the woods— were a talisman for Brown. She insisted that one of her books be covered in real rabbit's fur, and specified its size too. The compelling Little Fur Family (Harper & Brothers, 1946) measured just over three by four inches, and its size seemed perfectly in tune with the tone of the book. This odd little family was "warm as toast, smaller than most, in little fur coats, and they lived in a warm wooden tree." Garth Williams drew the expressive little creatures; a year earlier he'd illustrated Stuart Little, by E. B. White, another cherished author in Nordstrom's stable.

The first printing of Little Fur Family ran to more than 50,000 copies. Even a rough estimate suggests that at least 15,000 dead rabbits were needed to keep the little books warm. (Moths in Harper's warehouse had a field day, destroying hundreds of copies.) At least one bookstore owner wrote to express her horror. Nordstrom assured her that only "remnants" had been used, that "no rabbits had perished expressly for the sake of the book."

Brown was as unsentimental about animals as she was about children. In a revealing biography of her, Awakened by the Moon, reissued by William Morrow in 1999, Leonard S. Marcus relates that when one of her pet rabbits died she "skinned the carcass for its fur." Every winter Sunday, she headed to Long Island to join a sporting fraternity called the Buckram Beagles. The sport was "running to hounds"— or "beagling," for those in the know—and Brown relished the cross-country run, leaping over fences and crashing through brush after beagles on the scent of a jackrabbit. Exhilarated, she was often first to reach the hounds and salvage a bloodied rabbit's foot. Bruce Bliven's roommate, E. J. Kahn Jr., joined her one weekend. "The beagles of which she is part owner," Kahn wrote in The New Yorker some weeks later, "have eaten rabbits in rose gardens, hothouses, swimming pools, and tennis courts.... She is not bothered by the sight of a lot of dogs killing a rabbit." Kahn returned to Manhattan utterly drained after the 14mile trek, confessing that "for several days afterward I had difficulty walking at all, even on a Persian rug."

Brown wrote many of her stories in a small, wooden house known as Cobble Court. Tucked out of sight at 71st Street and York Avenue on Manhattan's Upper East Side, it would have suited an oversize doll. "There was a fire burning upstairs and downstairs and the smoke went up the chimney and into the city air," the author wrote of it in The Hidden House (Holt, 1953). "And no one knew where that sudden smell of sweet wild wood smoke came from in the middle of the big iron city." (Slated for demolition, Cobble Court was moved to the West Village in the late 1960s. The private residence now hugs the wall of a six-story apartment building near the corner of Charles and Greenwich Streets.)

Three young brothers often knocked on Cobble Court's door after school, and Brown was never too busy to see them. "She would give us Golden Books with blank pages," says Austin Clarke, now 58. "I would draw pictures and dictate the words to her." Together they wrote The Sailor Dog for Golden Books, which pioneered the mass marketing of inexpensive books. (Brown applauded the trend. "There's no such thing as a cheap book," she said.) Before her death, Brown had insisted that Austin share authorship. He receives royalties, though it was only in June of this year that he first saw a printing of The Sailor Dog with his name beneath that of Margaret Wise Brown's, included in A Family Treasury of Little Golden Books.

Cobble Court was Brown's city hideaway, but she had another whimsical retreat, on an island off the coast of Maine. She called it the Only House (except that it wasn't; even here she made room for Strange, building her a cabin, which Strange rarely visited). It had no electricity or running water, the washstand was beneath an apple tree, and the outhouses' scenic locations were a challenge if you were in a hurry. "Going to the Only House was like entering one of her stories," says Bruce Bliven. "She'd send me to the third rock in the stream, and I'd find a bottle of white wine. We'd eat 'Maine sushi' by grabbing live lobsters, smashing them against the rocks, and taking the meat out of the claws." Laurel Galloway remembers making paths of soft moss through the Maine woods with her godmother.

It was here that Brown wrote The Little Island (Doubleday, 1946), using the pseudonym Golden MacDonald:

Nights and days came and passed And summer and winter and the sun and the wind and the rain.

And it was good to be a little Island.

A part of the world

and a world of its own

all surrounded by the bright blue sea.

Leonard Weisgard's illustrations for The Little Island won him the Caldecott Medal in 1947. He described how, when he went to the Only House to paint, he was "cheered and distracted by squeaky bats coming right into the attic, bees humming in the fruit blossoms, waves slapping alongside the dock, and whiffs of fish chowder cooking in the kitchen." Weisgard was careful about opening the upper door: it led to a 10-foot drop to the ground below. ("We called it the Door to Nowhere," says Galloway.)

Brown's most fruitful collaboration was with Weisgard (they produced 25 books), but her most successful partnership by far was with Clement Hurd. In 1947, Harper & Brothers published Goodnight Moon. In a 50th-anniversary retrospective of the book, biographer Marcus says that what Brown initially called "Goodnight Room" was a dream she retrieved upon waking, reading it to Nordstrom over the phone later that morning. An early version of the story included the closing lines "Goodnight cucumber / Goodnight fly." But this time Brown didn't need Nordstrom's prodding to rethink the ending. The little bunny in his blue-and-white striped pajamas feels ready for sleep (the mantra of familiar objects in the great green room is finished), and it's safe to make a brief leap to the outside world with the book's last words: "Goodnight stars / Goodnight air / Goodnight noises everywhere." Brown's extraordinary facility for seeing the world through the eyes of a child was never sharper than in Goodnight Moon.

Brown's instincts told her that only Clement Hurd's pictures would do, and she waited for the illustrator to return from the Pacific, where he had served during World War II. Brown lent Cobble Court to him and his wife—with instructions from Nordstrom to create a "fabulous room"—and suggestively provided him with a reproduction of Goya's Boy in Red. (Brown was a competent oil painter and would often attach a color swatch, or a copy of a famous painting, to her manuscripts.)

Hurd, who had studied painting in Paris with Fernand Leger, excelled at the rich, almost surreal interior: a full moon rising beyond the billowed curtains, "a comb and a brush and a bowl full of mush" so simply drawn. It was the characters that slowed him down. By the third set of drawings, a mother and child had become a mother rabbit and her baby bunny. (Brown and Nordstrom thought he was much better at depicting rabbits than people.) "Brown's relationships with other illustrators were charged— this one was not," says Barbara Bader, whose definitive history of children's picturebook publishing in America will be reissued next year by Winslow Press as The World in 32 Pages. "Clem Hurd didn't have an artist's ego. He had a good life, a good wife, and didn't need to take himself so seriously." (It's a trait he put to good use when Nordstrom asked him to blur the udders on the picture of the cow jumping over the moon, in order to avoid offending conservative librarians.)

Despite the teamwork of two extremely talented artists, Goodnight Moon didn't make much of a splash at first (though The New York Times likened the story's rhythm to "the sing-song of disconnected thoughts with which children so often put themselves to sleep"). The hugely influential ex-head of Children's Services at the New York Public Library, Anne Carroll Moore, refused to recommend the library's purchase of a single copy—but Brown and Nordstrom couldn't stand her, so they likely took that as a compliment. In fact, the library didn't even stock Goodnight Moon until 1973, though now it appears on its Books of the Century list.

Through Brown's unusual bequest, royalties from Goodnight Moon, The Runaway Bunny, and other titles have sent almost $5 million Albert Edward Clarke Ills way.

"In this licensing-mad world, everyone wants to use it for something," says Thacher Hurd, who owns the rights to his father's illustrations. "But the book itself seems to stand somewhere else, a little above and beyond, always mysterious, never defined." Paradoxically, though, the book did help define our modern perception of a child's bedtime story. "By God, you can see Brown's legacy," says Susan Hirschman, a former colleague of Ursula Nordstrom and founder of Greenwillow Books. "She included all the things that would have seemed too little, and increased the awareness of all the adults who used her books. That line 'Goodnight mush'—it's true; it matters to a child. She's an icon in this industry, an American Beatrix Potter."

Despite Brown's troubled relationship with Michael Strange, by the late 1940s she had produced more than 50 highly original books for children. Under Strange's influence, she made strained attempts at poetry and short stories for adults, but she couldn't get them published. Surprisingly, Strange also wrote children's stories, which never made it into print. One of these, "The Two Bunnies," tells of a bunny who "always had an answer" and another who "always lost his head." While a little boat is sinking, Rabbit M.D. admonishes the Bunny No Good for neglecting to "bring the oars, and to cork the boat, and to bring the sail," whereupon the bad bunny cries, "Too true, too true." Strange continues, "Now there was one thing the Rabbit M.D. loved above everything else, and that was humility in someone else." If Brown read between the lines, she kept it to herself. "Dearest My Rabbit," Brown wrote to Strange, "Don't loose [s/c] these. I think they are so funny."

In 1950, dying of leukemia, Strange traveled to a clinic in Switzerland for treatment. Brown followed, but Strange would not see her. By November of that year they were reconciled, however, and Brown was at Strange's bedside in Boston when she died. It was finally, and with some relief on Brown's part, "the end of an apprenticeship," according to Marcus. "If the older woman had played 'big poet' to her 'little poet,' Margaret would now assume the larger role herself."

Brown was as prolific after Strange's death as she had been before, with nearly 20 titles issued between 1950 and 1952 (and more than 20 issued posthumously). The author was now writing songs too; Burl Ives had already recorded Two Little Trains (W. R. Scott, 1949) and was eager to put more of her books and songs to music. Innovative ideas continued to pour from Brown as naturally as water flows downstream, but none of them worked for adults. "God, what puppets we grown-ups are to the dreams or imaginings of childhood," she mused. "Someday I'd like to write something serious when I have something to say. But I am trapped in my childhood. That raises the devil when one wishes to move on." Despite the fact that she was, in Bader's words, "the first ... to make the writing of picturebooks an art," the author never quite realized what precious gifts she was bestowing upon America's children.

In the spring of 1952, just shy of her 42nd birthday, Brown met James Stillman Rockefeller Jr. Sixteen years younger than Brown and a recent Yale graduate, he was the son of James Stillman Rockefeller and Nancy Campbell Sherlock Carnegie. He'd gone to Cumberland Island, Georgia, most of which his family owned, to repair his sloop, Mandalay. Taking a role in his family's financial empire was anathema to him. He planned instead on sailing through the South Pacific "to see what others had done—and why_I wanted to look on broader vistas, before I chose my own." He certainly wasn't expecting to fall in love with a children's author.

ames Rockefeller is an unpretentious man. He lives high on a hill in Maine with a view out to the North Atlantic. In faded corduroys and a baseball cap, he drives his Jeep 4x4 along the coast with a posse of faithful dogs, and he still lives in the red farmhouse he bought almost 50 years ago. He says it was love at first sight when he met Brown that spring. "After a few days with the Bunny I wasn't sure whether people acted like animals or animals like people," remembers Rockefeller. "She made the simplest thing an adventure." In their time together on Cumberland, Rockefeller showed Brown how to gut and skin the deer they'd eat that week; she taught him how to shirr an egg in a large cockleshell. "She would have made a good cave woman," says Rockefeller, "going hunting and painting animals on cave walls."

CONTINUED ON PAGE 187

"The Bunny would have made a good cave woman," says James Rockefeller, "going hunting and painting animals on cave walls."

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 182

They spent a month together at the Only House. They swam in the granite quarry and picnicked on its ledge. Rockefeller sailed Brown's dinghy while she smoked a pipe, a bottle of white wine trailing in the water behind them. She introduced him to the magic mouse at the edge of the spruce forest and showed him the fairy ballroom, where she said little people danced at midnight. "She lived in her own no man's land between childhood and the grown up world," he once wrote. "I wonder if her books would have changed if we had had the children we talked about?" Before leaving the Only House that summer, he presented her with a platinum ring.

In late September, Rockefeller saw Brown for the last time, on board the SS Vulcania before it left for Cannes. Brown was on her way to the South of France for a brief holiday before embarking on her new life as Mrs. Rockefeller. She took her Kerry blue terrier, Crispin's Crispian (from Shakespeare's Henry V), with her, as well as French editions of her latest book, Mister Dog: The Dog Who Belonged to Himself. Named Crispian like her pet, the dog in the story meets a boy who also "belonged to himself," and it's hard to resist making the leap from the little boy to Brown, who was asserting her independence at last.

"One eats souffles and tomato provenpale and huge lovely salads," she wrote to Rockefeller. "But The Bunny has to watch it, and is going to run up and down the goat path in the mountains to the sea so she won't get too fat to climb the rigging for Pebble in the teeth of a gale with her white Catalyst ring flashing in the lightning." (Rockefeller was "Pebble" to close friends.)

At the end of October, complaining of abdominal pains, Brown was rushed to the hospital in Nice. Doctors removed an ovarian cyst and her appendix. ("I have it in a bottle," she said in a letter to Roberta.) For two weeks she rested, charming the nurses and writing to friends. Rockefeller was about to leave Miami on Mandalay. They planned to meet in Panama for a quiet marriage ceremony, and then to set out on their honeymoon sail through the South Pacific. "Every evening I will come when the light changes," Brown wrote to him from her hospital bed, "and give you an extra hug around the world— so hard your flippers will beat like a porpoise slapping the waves." She signed the letter in anticipation, "Your rabbit wife."

Brown rewrote her will then, as she'd done many times before. (A will drafted in 1948 had left everything to Michael Strange; co-executor Bliven says that in another everything went to her dog Crispian.) This time she named Rockefeller "first of kin and closest," bequeathing him the Only House and "anything of mine he wants." In a kind of fairy-tale twist, she had already chosen young Albert Clarke as the beneficiary of her most valuable royalties, including those from Goodnight Moon and The Runaway Bunny. He was then nine years old, the middle of the three brothers who had spent so many afternoons at Cobble Court.

Brown was ready to leave the Nice hospital on November 13. To show how fit she was feeling, she kicked up her leg cancanstyle. Then she blacked out, and less than an hour later Margaret Wise Brown was dead. That high-spirited kick had sent a blood clot rushing to her brain.

Nearly 50 years after her sudden death, Albert Edward Clarke III continues to reap the benefits of Brown's unusual bequest—royalties from Goodnight Moon, The Runaway Bunny, and dozens of other titles have sent almost $5 million his way. Yet Clarke, now 57, struggles to manage the money, as well as other aspects of his rootless life. In and out of trouble with the law since he was a teenager, Clarke has moved so often that his one remaining brother has given up trying to find him. "The family speculation about his inheritance," says Austin, the brother, "was that she knew he'd need the money." Clarke's uncle, James MacCormick, describes Albert as "very intense, quite different from his brothers. You felt uneasy around him as he got older. But I remember Margaret saying that if she ever had a child she wanted him to look like Albert." Maybe that is why Albert persists in the delusion that he is Brown's child and was adopted by Joan and Albert Clarke Jr.

As for Brown's "first of kin and closest," James Stillman Rockefeller Jr., he moved to Maine not long after her death. At 74 he still flies his Piper Super Cub over the islands that Brown taught him to love so much, and most summer weekends he and his wife, Marilyn, sail to the Only House. Rockefeller has nurtured its magic, for even his grandchildren follow in Brown's footsteps. They stoop to whisper to the mouse in the magic mousehole, and spy on the little people who dance in the fairy ballroom at midnight. "It was her gift of the Only House that kept us close," reflects Rockefeller. "Despite the other wonderful women in my life, I'll never get over her."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now