Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowThe Lost Sketchbooks of Albert Speer

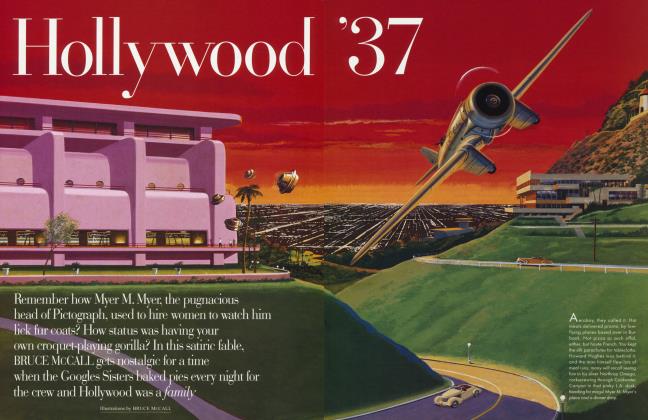

After Hitler's official architect, Albert Speer, left Spandau prison in 1966, he had big plans to rebuild his career on the other side of the Atlantic-or at least that's how BRUCE McCALL tells it

BRUCE McCALL

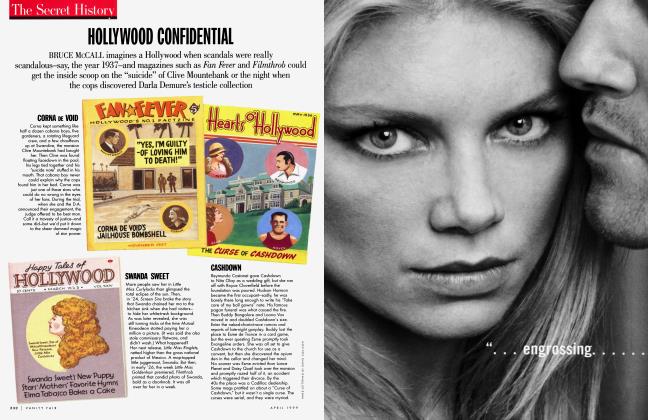

FORGOTTEN PAST

Statues of the Four Unknown Bowlers, each on the verge of ecstatic release; a vast domed interior; a single towering entrance; a steep bank of steps serving to expose and separate out the weak and infirm: this citadel of pure athleticism is Speer at his most visionary—and least practical. "All's we wanted was a roofing job and a new sign," huffed vexed Bowl-O-Rama proprietor Mel, "and this nut in a trench coat comes up with a Taj Mahal!" Speer later tried selling the same plans—Unknown Bowlers converted to Unknown Carpet Layers—to the House of Shag down the way, but again without success.

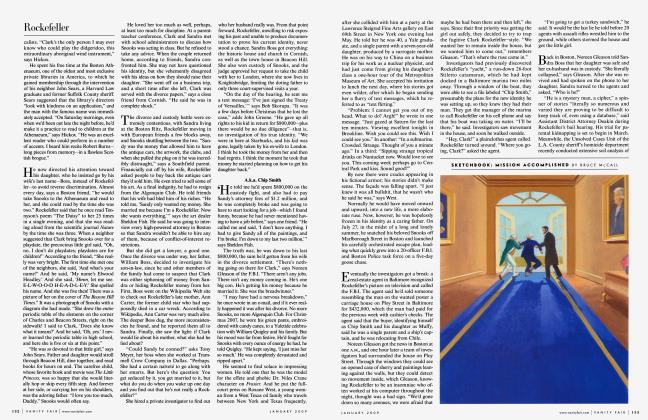

prung from Spandau prison in 1966 after 20 years with little more to his name than a 50-deutsche-mark bill and a new ankle-length leather raincoat, Albert Speer wasted no time calling in his chits among old rocketeer chums now working for NASA. If they'd help him find architectural work in the United States, he'd bum certain sensitive wartime documents. That the official architect of the Third Reich should be scrabbling to bid on this fast-food outlet or that souvenir stand in the American hinterlands may seem a colossal comedown; Speer saw it as the start of his comeback. Forbidden to practice in a Europe that refused to let bygones be bygones, he meant to glorify even the humblest of projects with his bold and monumental vision. Soon enough, he believed, as evidence of his genius spread, America too would fall for the unique architectural style that had dominated pre-war Germany.

This was not to be. Speer's compulsive reliance on the brutish mass, the soaring column, and the mile-wide avenue may have thrilled his megalomaniacal patron Adolf Hitler; applied to a Tulsa shoe store or a Bakersfield Moose lodge, these motifs clashed with the democratic vernacular and were, in some cases, counterproductive from a mercantile point of view. Again and again, his ambitious solutions were submitted, rejected, and forgotten. Trapped in the one idiom he ever knew, Speer could only be Speer. Careerwise, it was three Reichs and you're out.

Albert Speer died in 1981 without seeing a single one of his post-Spandau visions realized in windowless stone and concrete. His American sketchbooks vanished into limbo with him—until early this year, when, in a thrift shop in Munich, a sheaf of papers was found sewn into the lining of a long leather raincoat. It was Speer's long leather raincoat, of course, and those papers were Speer's lost sketches, secreted away for fear of sullying his legend with evidence of utter failure.

Here, then, the lost sketchbooks of Albert Speer: haunting images, unseen for decades, marking the final bizarre chapter of the 20th century's most controversial architectural career.

A curiosity, often misattributed to a secret Speer-Hitler pre-war project to "Germanize" American landmarks after invasion and conquest. The facts are more mundane. One of Speer's Spandau cell guards in the early 50s was an American private and baseball fan. No novice at currying favor, Speer produced this fanciful if somewhat inaccurate (dead center field lay 850 feet from home plate) view of Yankee Stadium as a "friendship token." He was duly rewarded with the odd candy bar and removal of hypochondriacal motormouth Rudolf Hess from the adjoining cell.

Soaring verticals had marked many a previous Speer concept, most notably his "cathedral of ice" for the annual Nuremberg party rally in the 30s. Transplanted to the Arizona desert in the form of three identical aluminum towers, the idea might well have worked to lure tourists from miles around to the roadside stand below, evoking the awe that buckles resistance. Proprietors Ma and Pa Jeeter had been thinking more along the lines of a repaint and a new screen door; accustomed to limitless government funds, Speer took things rather further. His bid, $15.9 million over budget, was regretfully declined.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 196

As with so many Speer buildings, this automated car wash seems to pin the onlooker to the ground and render mere humansand their cars—insignificant, while virtually demanding patronage, now. Yet there are brilliant flashes: wash suds recycled to create an imposing illuminated waterfall, both a functional cue and—with its roar magnified via loudspeakers—a symbol of raw power; a multitrack pass-through handling 2,000 autos per hour; twin "eternal flames," a favorite Speer theme here used to signal an open-24hours policy. Pompous overstatement for a mere car wash? Perhaps. The architect himself met such quibbles with icy disdain: "Next to Speer," he thundered, "even Ozymandias looks shy."

Stark and almost grimly functional, Floyd's cast-concrete Kozy Kabins allowed—indeed, ordered-guests to drive their cars directly into their cabins. But what to make of the twin guardhouses at the south entrance, superfluous if not outright overkill in most motor-court designs? Floyd took this, as well as the cabins' total lack of fenestration and a paved landscaping plan relieved only by artificial palm trees, as a hint that Speer might lack a certain feel for the tastes of the American traveler. The rejection of his proposal broke Speer's heart. Vowing to never again waste his genius on the philistine American, he had just begun sketches for a new police academy in Paraguay at the time of his death in 1981.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now