Sign In to Your Account

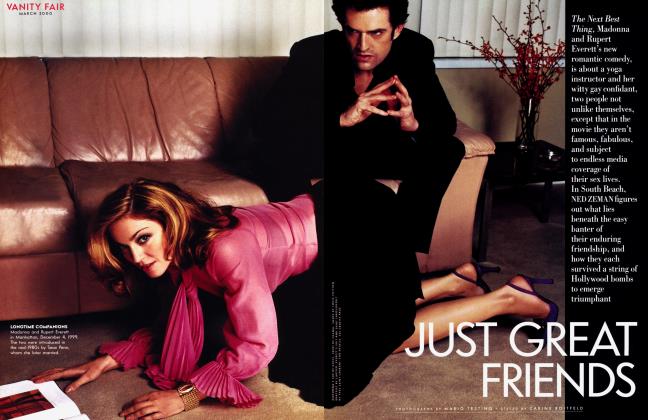

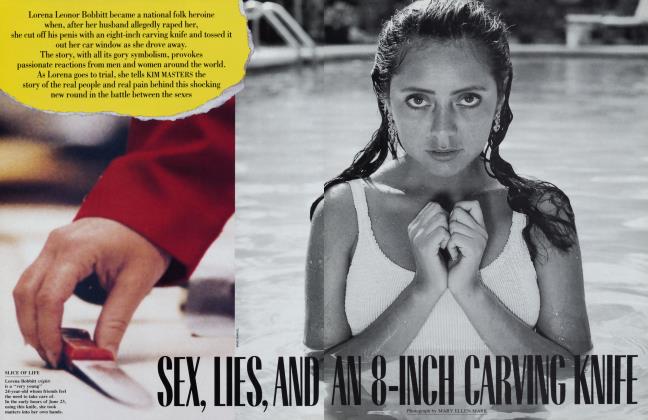

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowDISASTER AMID THE STARS

SHOW BUSINESS

Planet Hollywood, the movie-themed restaurant chain powered by Bruce Willis, Sly Stallone, and Arnold Schwarzenegger, is in financial trouble. How did producer Keith Barish and restaurant executive Robert Earl persuade so many A-list investors to climb aboardand what caused it all to go so wrong?

KIM MASTERS

f a sucker weren't bom every minute, maybe the entertainment industry would occupy just a few unfashionable blocks in some comer of the San Fernando Valley. But movie men were shearing sheep long before Transamerica lost its pants on United Artists in 1981 or Sony wrote off $3.2 billion on Columbia Pictures in 1995. And the entertainment business regularly taps into new sources of income no matter how many are sent packing with their pockets emptied.

Every so often, however, the hustlers get hustled. And therein lies the mystery of the phenomenon known as Planet Hollywood, which has now crashed to earth. Was it a fabulous idea that simply got too big too fast? Or was it, as some familiar with its founders suggest, a rather-too-risky business, based on rapid and manifestly unsustainable expansion?

Planet Hollywood, which has plenty of experience with dazzle, can mount a pretty good case for itself. The restaurant openings—and there were quite a few of them— became events that attracted huge crowds and loads of media attention. Many of the stars were entranced. "No Hollywood premiere can touch the rush," explained shareholder Bruce Willis. Sylvester Stallone another shareholder, said each event was "like a rock concert—a happening." So thought many financial analysts, who gushed over the stock.

Planet Hollywood took some very big stars, agents, and executives along for the ride—not to mention one of the industry's most prominent lawyers.

"Sly was more interested in promoting Planet Hollywood than his movies," says one of his associates.

Two shrewd marketers—movie producer Keith Barish (Sophie's Choice, Ironweed) and restaurant executive Robert Earl, who got his start in medieval-style theme restaurants—recruited an army of true believers who backed the chain even while others questioned whether it could possibly live up to its own hype.

In 1991 the chain opened its first restaurant in New York; at its peak there would be some 75 Planet Hollywoods in locations around the world. Soon after the company went public in 1996, its valuation was more than $2.5 billion. But by August 1999 shares had fallen to 75 cents, trading was halted, and soon thereafter the company filed for bankruptcy protection.

Though Barish and Earl are now estranged, they are united in maintaining that if anyone in this drama got burned, they did. In February 1999, Barish sold part of his stake for $17.5 million. At an average of $1.75 a share, he did not get a handsome price for stock that had traded in the 20s only a couple of years earlier. Earl says he never sold any stock at all— which means that a stake once worth $800 million on paper has now all but lost its value. "That's a lot of money I left on the table, isn't it?" he says. "And I'm still smiling." And hustling. Even with Planet Hollywood at its nadir last December, Earl was repeatedly promising that the chain would emerge from bankruptcy rapidly (as it did in late January). He also boasted about unnamed "new stars" who would bolster Planet Hollywood, and even said some locations would be added.

In the early days there was an unmistakable thrill associated with Planet Hollywood. Each restaurant was an expensive, high-profile proposition, at least in theme-restaurant terms. Thousands of people thronged to Planet Hollywood openings, amid flashing lights and throbbing rock music. The interiors were packed with Hollywood memorabilia—Katharine Ross's wedding dress from The Graduate, Sharon Stone's ice pick from Basic Instinct, a shrimp boat from Forrest Gump.

Among the many celebrities who lent their images to Planet Hollywood was Bruce Willis. "Bruce Willis was an unbelievable soldier," says a veteran Hollywood lawyer. "He was amazing, what he did for these guys. Whatever they paid him wasn't enough." In the early going, the gimmick was to have Willis tend bar for a few minutes. At later openings, he played with his band.

Stallone was another trouper. "Sly was more interested in promoting Planet Hollywood than his movies," complains a veteran of films with the star. Stallone, he continues, was "obsessed." But if Stallone was close to Earl, an agent involved in the chain says, Earl was even closer to Arnold Schwarzenegger. "Earl loved hanging around with stars," he says. "He and Arnold were the real twins, not Arnold and Danny DeVito."

Many other stars seemed to be enthralled by the idea of being players in Planet Hollywood— so much so that they didn't seem to notice the restaurant chain's profits and losses. Some saw it as a chance to promote themselves; some signed on just for the right to use the Planet Hollywood jet. "The big idea of Planet Hollywood is that stars are stupid," says one prominent producer. "Take Cindy Crawford, who makes millions in endorsements. For free plane time, she's willing to let them use her likeness and face. If you said, 'Let me use your face to sell Preparation H and give you nothing for it,' she'd say, 'Are you crazy?' But plane time—what's it cost to fly cross-country? Fifty thousand dollars? She could write the check herself and not have her face used to sell T-shirts and hamburgers."

"They treat show-business people like morons, which they are," a well-known manager concurs.

Crawford's agent, Michael Gruber of Creative Artists Agency, says his client received stock options as well as plane time, and only participated in Planet Hollywood events when she could combine them with other business. "If they help you get where you need to go ... does that outweigh not getting cash for an appearance?" he asks. Besides, he adds, "if she had fun at the party, then it's not work."

And the stars were not really expected to do any heavy lifting—or even to hang out with anyone except one another. By one account, contest winners who crossed the country to meet Demi Moore at a New York event got to spend a glorious 35 seconds in her presence. In fact, Barish says, stars loved the Planet Hollywood experience so much that many showed up for free. "There's almost no star, from Clint Eastwood to the Olsen twins, who at some point wasn't involved," he says. It was true: Antonio Banderas and Melanie Griffith, Mel Gibson and Danny Glover—even today, Earl throws around Will Smith's name like birdseed.

And if the stars enjoyed the openings, an anonymous executive such as Craig Baumgarten, who had been going on Hollywood junkets for years, could hardly be expected to be immune to their pleasures. "You'd get picked up in a limo, flown in a jet," he says. "If you wanted to play golf, go horseback riding, paragliding, they set it up and they'd pay for it. You understand why they'd do it for Bruce Willis, but here were all these studio executives and agents."

A prominent producer who attended a London opening was also impressed. "It was better than any premiere I ever went to in my life," he says. "He really knows how to work it, Robert Earl."

But the Planet Hollywood saga begins with Keith Barish, an affable, babyfaced man with a prominent forehead. And if anyone had cared to inquire, it would have been ridiculously easy to learn that Barish, a University of Miami dropout, had some unhappy investors in his past. In the mid-60s, when he was still in his early 20s, he formed a Bahamas-based company that pioneered the idea of creating a mutual fund through which foreigners would invest in U.S. real estate. His partners were Rafael Navarro, a Cuban emigre who had been a leading mutual-fund salesman in Panama, and Pierre Salinger, the press secretary to John Kennedy, whose Camelot luster added respectability to the enterprise.

By 1969, Barish, only 25 but already decked out in expensive Fioravanti suits and armed with an engaging smile and a dry wit, announced plans for his Gramco fund to buy more than $600 million worth of property. In a glossy 21-page advertising insert that was placed in major magazines, Barish cast his business in philanthropic terms: he was interested in "responsive capitalism" that would "make the world a better place to live."

But the whole notion of a fund that invested in hard-to-value real estate was controversial, and Gramco engaged in some unusual financial practices too. During the summer of 1970, for example, media reports questioned the high fees that Gramco squeezed out of its investors for managing the fund. Some of that money was channeled to Amprop, a profitable Miami realestate company owned by Barish. In September of that year, the West German government banned Gramco sales. There was a devastating run on the company.

Barish sold out in 1971. Many angry investors had lost money, but Barish was never found to have done anything illegal. For the next several years he was involved in private speculation in Florida real estate and in currency trading. By 1977 he was bored and looking for a new challenge.

Perhaps it was inevitable, given his highflying ambition, that Barish would end up in Hollywood. In the late 1970s, through William Morris agent Stan Kamen, he bought the movie rights to the novel Endless Love and became a producer of the cloying 1981 Brooke Shields vehicle. Jon Peters—who also has a producer credit on the Film—says that Barish, beneath his charm and quirky humor, struck him as an angry man. He remembers a particular meeting: "Barish was doodling," Peters says. "At the end of the meeting, I picked up the piece of paper.... He drew me as a devil." Barish says he just liked to draw demons. "It was not Jon Peters," he says. "I used to doodle all the time. I should stop doing it."

Barish made more headway through Kamen. The legendary agent never emerged from the closet during his lifetime, but many associates say he and Barish were very close friends and maybe more. Barish—a married man—scoffs at the idea. "We didn't live together," he says. "That was rumored. As [a screenwriter friend] said, I was never Stan's type." The two did, however, buy a house in Hawaii together.

Kamen offered Barish the opportunity to buy the rights to the William Styron novel Sophie's Choice. That film was a critical success in 1982, and Meryl Streep won an Oscar for best actress, though it grossed only $30 million. Barish also had a credit on the steamy 9 1/2 Weeks, with Kim Basinger, and Big Trouble in Little China, starring Kurt Russell. None of his films was particularly successful at the box office.

But Craig Baumgarten, who worked for Barish's production company in the early 80s, maintains that Barish was in big demand. "Barish came to Hollywood with a bag full of money, and everyone wanted to see him and take advantage of him," Baumgarten says. Barish was willing to return the compliment, according to his former colleague. "I used to sit in a room with him and watch him promise anything to anyone and then bald-faced deny it," Baumgarten says. "He would promise deals, he would promise jobs, he would promise scripts." In the end, Baumgarten concluded that Barish's allure was pretty superficial but still effective. "You can never overestimate people's willingness to believe flattery, especially when you're dealing with the egos of this town," he says.

As he had with his real-estate fund, Barish once again tried to drape himself in a do-good mantle. After making Sophie's Choice, he vowed that he would limit himself to tony, highbrow material. At the time, he was living a very tony, highbrow life, with an enormous house in the Hamptons, a massive place in Bel Air, an impressive collection of Warhols and Lichtensteins, even a butler. He was investing in properties such as the Dennis McIntyre play Modigliani, many of which were never made into films.

Barish was originally represented by Skip Brittenham, a powerhouse entertainment attorney whose firm played cupid for Barish by marrying him to another client, Taft Broadcasting, in 1984. The new company, Taft-Barish, produced the 1987 Arnold Schwarzenegger movie The Running Man, a modest success at the box office, and initiated development on The Fugitive, which was produced by Warner years later and became a blockbuster. (Barish was credited as an executive producer.) But long before that Barish was growing disenchanted with moviemaking. A number of his former associates say he didn't particularly like the vagaries of producing and was happy to explore another way to use his links to the movie world.

Meanwhile, his relationship with his lawyers at the Brittenham firm had soured. Knowledgeable sources say that the attorneys took the unusual step in the late 80s of terminating the relationship and that Barish left bills unpaid, a charge that Barish denies. He acknowledges, however, that the rupture is something he now regrets.

But at the time, Barish turned to Jake Bloom, the shaggy, rumpled lawyer to the stars who was given to

Everybody bought in," says a Barish associate. "There was a lot of social pressure." hiding his girth under caftans and smocks.

It was a serendipitous move. The Brittenham firm represented Harrison Ford, but the bulk of its work was in television. It didn't have a stable of movie stars. Bloom did—Schwarzenegger, Willis, and Stallone, to name just three. And Barish had cooked up a big idea, or so the story has generally been told in press reports: he would start a chain of theme restaurants called Cafe Hollywood.

In fact, the idea had come from Bryan Kestner, who had begun his career in show business as Barish's handsome, Ferraridriving physical trainer and who had subsequently become a development executive at Taft-Barish. Barish confirms that Kestner came to him in the mid-80s with a concept called Hollyrock, for which he was paid a fee and received shares in the company. (Kestner says today that he has long felt deprived of credit for his brainstorm, and adds that he's been horrified as he's watched Planet Hollywood get "driven into the ground." His opinion? "There's a rat in the kitchen." While Kestner saw his stake in the chain rise at one point to more than $15 million, he, like others, made the unfortunate mistake of borrowing against the stock and was financially devastated when the price tanked.)

As in his previous ventures, Barish's motives for starting Planet Hollywood were partly noble. His hope, he says, was to create a place to enshrine imperiled Hollywood memorabilia. Oddly, in this era of soaring prices for collectibles, the studios have barely begun to preserve their own artifacts, many of which are simply carted off by actors, directors, and producers. Barish says he wanted to nurture Hollywood's own little Switzerland, as he puts it. "I wanted to cross agency and studio lines ... to have everyone be a part of promoting Hollywood movie stars and movies," he explains. "This was a permanent tribute to movies." Barish's erstwhile publicist, Bobby Zarem, helped develop the concept (Zarem, who has a knack for taking credit whenever it can be found, claims to have come up with the idea of involving stars), and in the late 80s the two went looking for a partner. Zarem says Barish became discouraged while Zarem unsuccessfully shopped the concept everywhere from McDonald's to Red Lobster. But Zarem eventually linked Barish up with Robert Earl, a diminutive Englishman who was then running the Hard Rock Cafe chain, for which Zarem was also working. (Zarem takes credit for inadvertently kicking off the whole commercial merchandising phenomenon when he started sending around Hard Rock robes and T-shirts in the 80s.)

Cocky and loquacious, brimming with confidence, Earl has a skill for painting the future in the brightest of colors and making remote possibilities sound like established facts. He was bom in Hendon, north of London, and had once dreamed of following his actor father onto the stage. Instead, he studied hotel and catering management at the University of Surrey. By the time he was 22 he had developed a site near the Tower of London into a medieval-style banquet hall which served packs of prepaid tourists delivered through deals with American Express and British Airways. Subsequently, Earl made his way to the Hard Rock, which was then faltering. Earl takes credit for turning Hard Rock around.

After Zarem brought Earl into Planet Hollywood, the two had a fallingout. Among other points of contention, Zarem says that Earl wouldn't share financial information and took credit for Zarem's work. Earl's ego, Zarem says, was "out of proportion to his height." Zarem negotiated a buyout and left. In his view, Earl was fixated from the start on the potential merchandising bonanza and cared about little else. Zarem says Earl had seen "an opportunity to take something that had value and to rape it and squeeze every cent out of it that he could."

Earl says he doesn't remember precisely what happened in his dealings with Zarem, but doubts Zarem's account is correct. "It doesn't sound very plausible," he says. "[This] gets him a few dots in the newspaper. At his delicate stage in life, good luck to him."

Hard Rock co-founder Peter Morton had his own issues with Planet Hollywood.

He sued in 1991, claiming that Planet Hollywood was nothing more than a Hard Rock rip-off. Morton's case was settled on terms that remain undisclosed. Earl says that while Morton likes to hint that he received a hefty payment from him, he never did. Morton won't comment. 2

The enthusiastic support of stars would be more important to Planet Hollywood than mustard and ketchup. According to Zarem, he and Earl met with Bloom about involving his star clients in the new venture. But Barish says he didn't need Bloom to get the so-called first tier of Planet Hollywood partners. Nonetheless, they still cut Bloom in on the stock, and his top clients became Planeteers, so to speak. Meanwhile, Barish approached Willis's agent, Arnold Rifkin, and landed the Die Hard star. He recruited Schwarzenegger on the set of Terminator 2. As for Stallone, " his career was slumping at the time, thanks to bombs such as Lock Up and Oscar. According to a source familiar with the chain of events, "Sly begged."

Before long, it seemed as if everyone had a piece of Planet Hollywood. Barish says there was no master strategy in terms of whom to recruit, but Planet Hollywood reached well beyond its A-list stars. Bloom was in (and so, in time, were clients Jean-Claude Van Damme and director John Hughes). Many agents also got stock: Arnold Rifkin; Ron Meyer, who represented Stallone; and Lou Pitt, who had Schwarzenegger. And the chain cut in Mark Canton, then head of Columbia Pictures. None of these men particularly enjoys talking about Planet Hollywood, and their stakes in the company have never been reported. But Earl cheerfully confirms that they were given "founder's shares." Barish denies that they received the stock to deliver their clients. But when it comes to explaining why, then, they were given shares, neither Barish nor Earl has much of an answer. "There was no great theory," Barish says. "It came about."

"Not one of these people ever would do anything that wasn't first and foremost in the interest of their clients," Earl insists. So why give them stock? "I don't think I really stopped or had time to think about it," he says.

Whether by design or luck, the stars were eventually encircled with representatives who had a financial interest in the restaurant chain. One of these advisers says he invested only after having tried to dissuade a major client from getting involved. "It was stupid to promote that stuff," he says, "but a client tells you he's going to do something, you hope it's good. He said he believed in it."

Stallone's involvement with the chain led him to drop his onetime stepfather, Anthony Filiti, as his financial manager. Admittedly, there had been some irregularities in Filiti's handling of Stallone's money, but Filiti maintained in a 1996 New York magazine article that the trouble really started when he questioned Stallone's participation in Planet Hollywood. Filiti said he raised these concerns, both in conversation and in writing, with Stallone's attorney Jake Bloom. In time, Filiti was replaced, at least temporarily, by David Rosenberg, Earl's longtime financial adviser.

Whether these rich and powerful stars needed protection in a deal in which they were given stock for showing up at big parties is open to debate. If the chain went south, the worst that could be said was that they had wasted their time, and maybe had taken a risk by associating their images with a company that scorched those investors who didn't sell while the selling was good.

Barish argues that the stars weren't exactly left without advisers. "They do have wives, managers, friends, and their own instincts," he points out. But in at least one case, apparently, Barish and Earl went after talent handlers with the explicit intent of ultimately hooking their clients. Hollywood's most prominent manager, Bernie Brillstein, says he and his then partner Brad Grey were offered 100,000 hours on the Planet Hollywood jet in exchange for helping to recruit Dana Carvey and other comics that the firm represents. They passed. "It was Steve Ross lite," says Brillstein, comparing Barish's and Earl's courtship techniques to those of the late, famously openhanded Warner chairman. "You want to go to Hawaii? Get on the plane. Here's a leather jacket that no human being should wear. Here's a T-shirt. Come on—be a star." Earl denies that an offer was ever made.

The family continued to expand. Rifkin client Danny Glover became a Planet Hollywood promoter, as did Whoopi Goldberg, then represented by Ron Meyer. And many Hollywood insiders invested in the company before it went public, among them Jon Dolgen, now chairman of Paramount, who split a $100,000 piece of the Washington, D.C., restaurant with Meyer. Jim Wiatt of William Morris and Jim Berkus of United Talent also bought in. Earl says there were dozens of such investors, nearly all "celebrity-linked."

One executive says the chain seemed like "a pretty smart formula to outmaneuver the studios in exploiting their own assets." But he says his involvement was motivated more by friendship than potential profit. "It was Jake and all the talent we did business with," he says. "I felt it was supporting people I knew." A former Barish associate adds, "Everybody bought in. There was a lot of social pressure."

Even the studios were offered a stake. But several studio chiefs declined to take it and were loath to give Planet Hollywood any of the memorabilia for which it clamored. Former Warner co-chairman Terry Semel says his studio only lent objects, and did so under strict conditions. "We felt we wanted our memorabilia for our own museum and our stores," he says. "We also felt that these things have great value in the future. Why would we give it away?"

Universal followed the same policy, according to former chairman Tom Pollock. "Universal declined to take stock in the company," he says. "We gave them the right to use the movie memorabilia. We made them sign a loan agreement that we could call at any time." Not surprisingly, given the company's aggressive guarding of its trademarks, Disney was the least cooperative studio of all, according to Barish, though Mickey Mouse did leave handprints at the Planet Hollywoods in Beverly Hills and Orlando.

But Planet Hollywood reaped enough rewards from its many relationships to adorn the walls of the rapidly expanding chain. All the gifts and loans were done in the name of promoting films and keeping major stars happy. "Planet Hollywood existed on free shit from the studios," says producer Craig Baumgarten. "Every time we made a movie, Keith would call and say, 'What you got?'" After Nowhere to Run finished shooting, the producer turned over Jean-Claude Van Damme's motorcycle.

Earl says Planet Hollywood did not exist off "free shit," but if the company depended on the goodwill of the studios, it couldn't have hurt to cut in a guy such as Mark Canton, who ran a big memorabilia factory at Columbia Pictures. Canton offered plenty of cooperation with the chain, but says he never worried about a potential conflict because he ran everything by the company or his lawyer, Jake Bloom.

"I wanted to cross agency and studio lines," says Keith Barish. "This was a permanent tribute to movies."

The risks in Planet Hollywood were glaring to some of those Barish and Earl tried to involve. Brillstein says the business didn't seem to make sense. "After you see Arnold Schwarzenegger's jockstrap, what do you go for?" he asks. "I don't know what the thrill was." A wellknown entertainment lawyer who declined to get involved in the deal remembers his thinking: "We said, 'Most restaurants don't work.' They had very heavy capital costs to build these things. They're very fancy restaurants.

"The big idea of Planet Hollywood is that stars are stupid," says one prominent producer.

And the prices were not like Spago. They couldn't get away with that. So they had to rely on merchandise."

Earl talked a lot about the "merch," and the markups on T-shirts, caps, and jackets at Planet Hollywood were huge. But it didn't seem like a solid foundation for the chain. "At the Hard Rock, Peter [Morton] ran a good restaurant," says this attorney. "He gets a lot of incremental revenue out of the merchandise." At Planet Hollywood, he says—echoing the views of several others in the industry—"the food was horrible. I said, 'This isn't going to work.'"

Indeed, it didn't take the public long to discern that despite the opening-night festivities and the memorabilia on the walls, Stallone and Schwarzenegger were unlikely to be haunting the place past the well-publicized opening—especially in Tennessee or Gurnee, Illinois. The cheeseburgers and chicken strips in sugary batter did not keep the crowds coming.

At first, Barish says, no one expected Planet Hollywood to generate a big financial windfall. "No one ever joined expecting to make a lot of money," he says. "We thought it would be a nice business. I never thought we'd go public."

But other Barish associates say he was inflamed with envy over the wealth of men such as David Geffen and Ronald Perelman, and dreamed of making a killing by taking a company public. In fact, Barish had explored selling shares in his production company in the 1980s, as many others (including Dino De Laurentiis and Karate Kid producer Jerry Weintraub) were doing very, very profitably at the time. Asked about this today, Barish initially denies that he ever harbored such an ambition, but then remembers considering and then ultimately dropping the idea.

Even if, as Barish maintains, he did not conceive of Planet Hollywood as a vehicle for going public, he still projected its future on a grandiose scale. His friend Mel Klein, a Texas businessman who introduced him to the future Mrs. Barish, remembers that Barish "said from the getgo that it would be huge." Zarem recalls that Barish said the chain could be "an international phenomenon." And Earl says he always imagined Planet Hollywood as "being global and being large."

As early as 1992, Planet Hollywood had struck a deal to allow Richard V. Allen, the former adviser to Ronald Reagan, to open franchises in several foreign cities, mostly in Asia. Allen later alleged that within a month Planet Hollywood had made yet another deal to form an Asian offshoot with Singapore billionaire Ong Beng Seng, who invested in the chain. Allen also said he discovered that Ong was looking for locations in Bangkok, which he claimed had been promised exclusively to him.

By the end of 1994, having paid $8 million for the rights to open in Seoul, Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur, Taipei, and Vancouver, Allen had managed to open only in Seoul. The restaurant failed, and Allen sold his interest in the remaining four franchises back to Planet Hollywood. He later sued for nonpayment; the litigation has been settled. "Planet Hollywood was a thoroughly revolting experience, not by virtue of its concept but by virtue of the way its principals handled their affairs," Allen says.

Certainly, Barish and Earl's ambitions for the business seemed limitless. By 1994 they had opened seven locations, from London to Phoenix.

With 32 restaurants and a profit of $26 million in its previous fiscal year, Planet Hollywood went public at $18 per share on April 24, 1996. The offering set a new first-day record for volume of trading (23.8 million shares) on the NASDAQ exchange. After soaring to more than $31, the price had settled at $26.88 by day's end, up 49 percent. The market had Planet Hollywood fever. The stock was trading at 67 times the company's prospective earnings per share. Just over 10 percent of the stock was in the public's hands; almost 90 percent belonged to insiders—primarily Barish and Earl, who together owned 57 percent. The average price paid by those insiders was about 36 cents per share.

Barish says the company's splashy public offering made people greedy. It certainly made Earl very outspoken about the grand scale of his plans. "I intend to build an empire," he told Fortune magazine. He envisioned Planet Hollywood toys (a Planet Hollywood Barbie, for example), fragrances, superstores, casinos, hotels. He wanted to build new restaurants; the sports-themed Official All Star Cafe chain and Marvel Mania, based on comic books. (There are now eight All Star Cafes, but Marvel Mania never materialized.) He talked of having more than 300 restaurants worldwide within a few years.

If Earl believed that all that was possible, many others were starting to have doubts. Several analysts were bullish, but others were becoming wary. In September 1996, five months after the public offering, the company reported that profits for the first six months of the year had plummeted to $4 million from $12.7 million the year before. And sales for restaurants that had been open for 18 months or more were flat. Sales of the all-important merchandise— the centerpiece of the Planet Hollywood strategy—were declining as a percentage of total revenue. Like many theme-restaurant chains, such as the Minnesota-based Rainforest Cafe, Planet Hollywood was struggling.

By the end of the year, any potential investor who could read would learn that several mutual funds had already dropped the stock. Ronald Paul, a food-industry consultant based in Chicago, was warning that Planet Hollywood was running out of "trophy locations," which were essential to its health. It was one thing to have a Planet Hollywood in a tourist destination, where there was plenty of traffic and it felt like an experience. It was quite another to open one in Indianapolis.

Planet Hollywood itself acknowledged in a 1996 public filing that it expected profits from future restaurants to be less than those generated by previously existing outlets. The chain was then counting on just 4 of its 45 units— the hugely successful Orlando restaurant as well as locations in New York, London, and Las Vegas—to generate 35 percent of its sales.

Nevertheless, Earl and Barish were doing very well indeed, on paper. In Planet Hollywood's brief heyday, their holdings were worth about $800 million each. And they were paying themselves annual salaries of $600,000 apiece and enjoying many perks. Earl was brimming with confidence. "I can guide anyone in my field on any problem from food poisoning to sexual harassment," he boasted to The Sunday Telegraph in Britain. "I'm a good sage."

And he dismissed an interviewer's questions about the chain's long-term viability by saying that he had just bought more stock, adding—in an awkward slip—"That's an indictment of how I feel."

In 1997, Time named Robert Earl one of the 25 Most Influential People in America. But in January 1998, Planet Hollywood announced that it had lost $44 million in the fourth quarter of the preceding fiscal year. The share price dropped to $7. Paul Marsh, an analyst at SG Cowen, said the stock was "fairly washed out."

By October 1998 the stock was trading at just under $4 per share. In November the chain reported a third-quarter loss of $10.1 million. Earl promised a successful restructuring. And there was another piece of news: Keith Barish had resigned as chairman, though he remained as a director.

In February 1999, Barish sold 10 million shares at an average of $1.75 per share. Shortly thereafter he quit the board. And a few days after that, Planet Hollywood announced a staggering loss for the fourth quarter of 1998: $228 million. Barish says he had decided to sell the previous November but was delayed because of negotiations with the company over the terms of the sale. Though he was still on the board when he made the sale, he says he had not been attending meetings and had no knowledge of the magnitude of the loss that was about to be announced.

Last May, the ever sanguine Earl reassured the shareholders that a turnaround was imminent. In August the company said it was filing for bankruptcy reorganization. Any of the stars who had settled for stock options, Earl now admits, were holding an empty bag.

Whether Planet Hollywood can survive is an open question. Though it may seem that only the most optimistic could hold out hope, Willis has predicted "a very dramatic comeback" for the chain. "They're going to ... close a few of the stores," he told the New York Daily News. "It won't be a loss. It'll be a gain." Schwarzenegger had been in there swinging on the Today show, but in late January he announced that he was severing his ties to Planet Hollywood.

The money may not have meant much to the stars, but it could have come in handy for the agents and executives. Perhaps the most vulnerable was attorney Jake Bloom, who had reportedly received nearly a million shares in Planet Hollywood. Even on the opening day, the stock would have been a substantial addition to Bloom's coffers; some of his clients may get $20 million per job, but he doesn't. A source close to Bloom says he didn't get nearly as much stock as his star clients. (Bloom reportedly had about 1 percent. According to Filiti, Stallone had close to 3 percent.) But to Bloom, it seemed, the stock had more potential importance.

'I think Jake Bloom does very well," a prominent attorney reflects. "But ... doing very well may mean $3 million a year. Now all of a sudden here's a chance. A guy like Robert Earl comes along and says this stock is going to be worth $25 million. It's tempting. It takes him into a whole different category. Now you're talking about buying a plane. Now you're talking about a house in Malibu to match the one at Sun Valley."

Bloom seems to be unhappy to have been so deeply involved, along with a number of his clients, in what was ultimately a losing enterprise. "I was disappointed it wasn't more successful," he says.

But his friends say Bloom didn't see how Planet Hollywood could fail, and never really worried about how the whole thing might look if it did.

"Jake doesn't think about these things," one lawyer says. "I don't think his mind is trained to deal with issues like that." A manager adds, "For a smart showbiz lawyer, he was really an innocent. [And] when it was riding high, no one said a fucking word except 'Jake's a genius.'"

The wealthy Hollywood players who lost their multimillion-dollar paper fortunes have absorbed the blow. Mark Canton, for example, is rueful but philosophical. "It was a nice ride for a short time," he says. "I think a lot of Robert Earl. I just don't know quite what happened."

Barish and Earl are vocal about the fact that they themselves took the biggest hits. Certainly, both suffered staggering paper losses—though one Barish associate offers the opinion that "the company provided a lifestyle" for the two men while it was still afloat. And neither has given up on the Planet Hollywood idea—although they have apparently given up on each other. The two no longer speak. But when it comes to the future of Planet Hollywood, they agree that going public was the downfall— though even on this count their analyses don't square.

Earl says the chain's problems were caused by having to report its financial results. "It got to the stage where if Planet Hollywood farted it wound up in the paper," he complains.

Barish sees things a bit differently. He sticks to his story that the chain was never meant to get so big. Going public, he says, "caused pressure to expand, and that wasn't the original intent." He was opposed to Earl's decision to create the Official All Star Cafes, which he says he felt was not a viable concept (though Bobby Zarem says the sports-themed offshoot was part of the original Planet Hollywood proposal). Barish says the quality of the food was a problem, too.

But both men are bullish on the chain's potential for recovery. "There's still probably 20 cities that Planet Hollywood should go into," Barish says.

"To this day," Earl insists, "we haven't maximized our trademark."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now