Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowWith his 1955 novel, Auntie Mame, Patrick Dennis launched an unforgettable character, played on stage and screen by actresses including Rosalind Russell, Angela Lansbury, and Lucille Ball. Now Barbra Streisand may be next, and a new Dennis biography is on the way. But while Dennis's life was just as flamboyant and eccentric as that of his most famous creation, it was far more mysterious

September 2000 Leslie BennettsWith his 1955 novel, Auntie Mame, Patrick Dennis launched an unforgettable character, played on stage and screen by actresses including Rosalind Russell, Angela Lansbury, and Lucille Ball. Now Barbra Streisand may be next, and a new Dennis biography is on the way. But while Dennis's life was just as flamboyant and eccentric as that of his most famous creation, it was far more mysterious

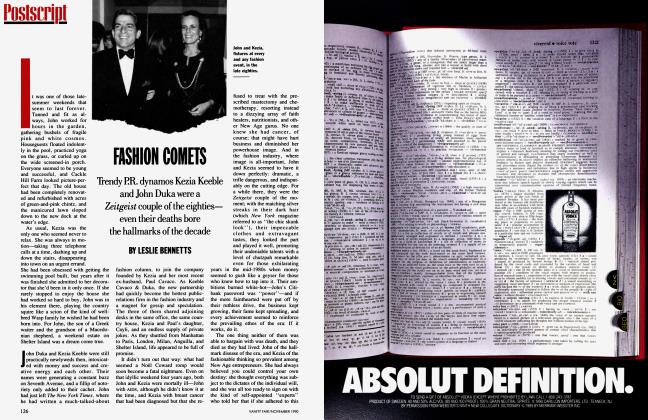

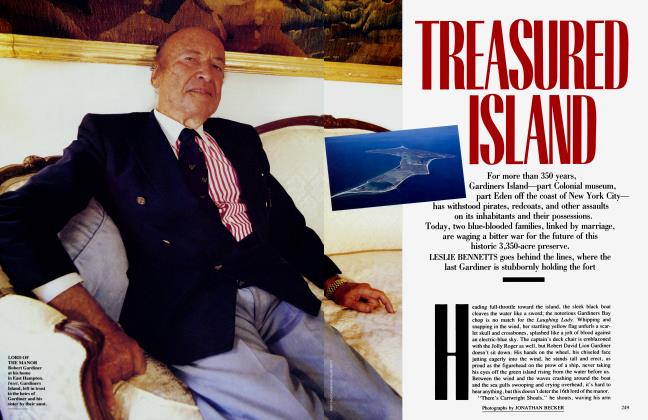

September 2000 Leslie BennettsAt the height of his success, Patrick Dennis was the toast of New York. The first author ever to land three books simultaneously on the bestseller list, he was most notably the creator of Auntie Marne, an instant classic published in 1955 that quickly inspired a hit Broadway play, a hit musical, and two Hollywood movies. A renowned host and bon vivant, the writer—whose real name was Edward Everett Tanner III—gave fabulous parties at his spectacular Upper East Side town house, entertaining Rosalind Russell, Cornelia Otis Skinner, Kenneth Tynan, Peggy Cass, and other friends in great style— and often in uproarious costumes. Armed with a martini, a cigarette, and a rapier wit, Tanner and his wealthy wife seemed to personify a kind of Nick and Nora Charles sophistication that defined mid-century Manhattan life at its most glamorous.

With two impeccably behaved children and a multitude of fans, Tanner had money, fame, charm, much-admired taste, and seemingly everything else a writer could want. As Marne herself says, “Life is a banquet, and most poor sons-of-bitches are starving to death!” Not Tanner: his lifestyle was as flamboyant as the irrepressible Marne’s, and no one could ever have accused him of failing to enjoy his good fortune.

But what his fans didn’t know was that Patrick Dennis was his own most ingenious creation. He was certainly exotic; amid the gray-flannel conformity of the 1950s, Tanner cut an arresting figure as he swept through the sedate streets of the Upper East Side. More than six feet tall, with a flowing beard that contrasted sharply with the close-cropped conventions of the era, he was more likely to be splendidly attired in an Edwardian cape or a homburg and furled umbrella, looking like “a refugee from the British Foreign Office,” as he put it, than in the sober uniform favored by his peers.

But his inventiveness went far beyond the sartorial. From his very name to the respectable upper-middle-class family life he had built for himself, virtually everything Tanner had constructed was an elaborate contrivance whose ostensible purpose was simply to amuse—but whose real effect was to conceal the truth.

And when it all caught up with him—when his writing went out of style and his books didn’t sell anymore, when sexual confusion had destroyed his family and alcohol had wreaked havoc with his personal life, when he had run through the fortune he had made and his seemingly enviable spree as a high-living expatriate had fizzled to a dissolute close—Tanner, in the final chapter of his ever surprising life, came up with perhaps his single most inspired idea. Reinventing himself one last time, Tanner not only lived out an outrageous fantasy that shocked even his closest friends, but also kept the best character he had ever dreamed up a secret that, in some ways, will forever remain an unsolved mystery.

When he died nearly a quarter of a century ago, he was already largely forgotten, or so he believed. But the stage versions of his work have never stopped being produced, with the play Auntie Mame and the musical Mame both perennial favorites, and Little Me, the Neil Simon version of another Dennis best-seller, produced on Broadway in a sold-out revival that won Martin Short a Tony Award for best actor last year.

And now—more than four decades after his greatest fame—Tanner is enjoying a resurgence of popularity that attests to his enduring appeal. This November, St. Martin’s Press will publish Eric Myers’s Uncle Mame, the first biography ever written about Tanner. Barbra Streisand will be the executive producer of and may star in a three-hour television version of Mame that is expected to be “ABC’s biggest-budget event movie ever,” according to Daily Variety. Bette Midler also has a Mame project in development, at CBS.

Many other legendary names have already portrayed Mame, “the middle-aged terror of Beekman Place,” a wealthy, eccentric bohemian who is thrust into an uncomfortably conventional role when she inherits her 10-year-old orphaned nephew. Rosalind Russell and Angela Lansbury were the original stage Mames, with Bea Arthur costarring with Lansbury in the 1966 smash musical production. Earlier this year, when Lansbury was honored by Southern Methodist University for her contributions to the arts, she and Arthur brought down the house with their onstage speculation about whether Streisand would indeed take on the role of Mame. “I think she will play it,” said Arthur. She paused for a crucial beat, and then added, “But not well.”

A huge success, Auntie Mame sold more that two million copies.

The casting of Barbra Streisand as an upper-class Wasp may seem novel, but the role of Mame has attracted a dazzling assortment of grandes dames over the years. One of the less fortunate was Lucille Ball, whose 1974 movie was a flop. This came as no surprise to Tanner, who had known she was the wrong choice. Miss Ball was “too common for the role,” he proclaimed. With varying degrees of success, the part has also been filled by Greer Garson, Beatrice Lillie, Constance Bennett, Elaine Stritch, Ann Miller, Celeste Holm, Sylvia Sidney, Ann Sothern, Juliet Prowse, Alexis Smith, Ginger Rogers, and even Gypsy Rose Lee. “Translated into more than 30 languages, Auntie Mame, and the musical Mame, have never ceased being performed somewhere in the world almost every evening since their respective Broadway debuts in 1956 and 1966,” wrote Richard Tyler Jordan, the author of a 1998 history called But Darling, I’m Your Auntie Mame!

Indeed, Auntie Mame has become one of the most beloved characters in the history of popular culture. “What is more exciting than a glamorous lady who has the ability to change people’s lives for the better?” says Jerry Herman, who wrote the music and lyrics for the original Broadway production of Mame, which ran for nearly four years. “Especially in times when we have problems, what better to escape to than the world of Mame Dennis? It’s a world of fantasy. She’s the Pied Piper, the Wizard of Oz. She’s a magical being that everyone would like to know.”

But if Auntie Mame is known around the world, the author who created the icon remained an enigma even at the height of his popularity. From his earliest childhood, Tanner had been rewriting his own life, reworking the aspects he found unsatisfactory and spinning his story into the first of the many tall tales he would later tell to such public acclaim.

Who was the real Patrick Dennis? In some ways, not even his wife and children ever knew for sure.

Even as a small boy, Tanner refused to conform to what was expected. The son of a stockbroker, he was born in 1921 in Chicago, where he grew up on Lake Shore Drive in relative prosperity, at least until the stock-market crash of 1929. Tanner’s compulsion to improve upon the truth began when little Edward wouldn’t answer to his real name, insisting that he be called Patrick instead.

And so the First of many aliases was bom. In later years Tanner’s other pseudonyms included Virginia Rowans (a nom de plume he used for four of his books), Desmond LaTouche, and Lancelot Leopard, the name he gave to his company when he incorporated his various business interests. (His friend Cris Alexander, an actor and photographer, designed the Lancelot Leopard logo, which featured Tanner, with a Roman helmet on his head, naked astride a leopard, brandishing a quill pen—an image he used for all his business stationery as well.)

To further complicate matters, when Tanner wrote Auntie Mame under the name of Patrick Dennis, he also bestowed the name Dennis upon Mame, compounding the confusion by calling her nephew Patrick—a choice that quite naturally led the public to believe that the author Patrick Dennis’s story about a little boy named Patrick Dennis, whose parents die and leave him to the care of an aunt whose life is an unceasing round of wild parties, was in fact the story of his own life.

Regrettably, the reality had not been nearly as entertaining. In his fiction, Tanner was able to kill off his parents with admirable dispatch, replacing them with Marne, who was infinitely more fun. His real parents proved a more persistent annoyance. “He hated his father,” says Michael Tanner, Patrick’s son. “He couldn’t stand him. He had nothing but terrible things to say about his parents—how stupid they were, what terrible lushes they were.”

Patrick’s mother was a stylish socialite who lived for the kind of pretentious upper-crust parties he would skewer in his writing many years later. “My father said she was a total idiot,” says Michael, a doctor who lives in Manhattan with his wife and their three-year-old son. Patrick’s father had been a football star in college, and he was appalled to find that his young son, who liked to write skits and put on plays, had neither the aptitude nor the appetite for sports. “He never threw me a baseball in his entire life,” Michael reports. “My mother used to take me to Yankee games; my father took me to the theater.”

As a vulnerable child, Patrick was deeply wounded by his father’s cruelty.

“I think my grandfather made my father for gay when he was about 10 years old,” says Michael. “My father never forgave his father for calling him a pansy.” (And yet despite his intense dislike, in later years Tanner secretly paid his alcoholic father’s salary so he could continue to believe he was gainfully employed. “His father was floundering, so it was out of kindness, but it was also like revenge,” explains Michael.)

From the outset, the Tanners established a family tradition of concealing uncomfortable truths that Patrick would later perfect in his own life. Patrick had a sister 10 years older than he, but his parents didn’t tell either child that their mother had been married before and that the children had different fathers. “That kind of hypocrisy was what my generation was brought up with,” said Louise Tanner, Patrick’s widow, in an interview before her death last spring at the age of 78.

Tanner escaped from his origins as quickly as he could, taking a course at the Art Institute of Chicago after finishing high school and then joining the American Field Service to become an ambulance driver on the front lines during World War II. “The day he left for Africa, he came over in a pith helmet and shorts and high kneesocks—this was on a cold day with snow on the ground—and said, ‘I’m going out to save the world—tata!”’ reports Katie Kelly, a childhood friend who now lives in San Diego. “He treated it as a joke.”

Tanner spent much of his early adulthood building a life that was a model of convention.

Tanner served with the armed forces of seven countries in the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe, and he was wounded twice, “once quite badly, in the face,” said Louise. “Later he was characteristically blase about his contributions to the war, but I have been told by people who were there that he was very brave.” Many years afterward, Tanner was awarded a posthumous Purple Heart, but during his lifetime he claimed, with typical insouciance, that “the greatest consequence of this era was cosmetic,” since his exposure to the luxuriantly bearded soldiers of the French Army inspired him to grow the beard that became his trademark.

Despite his pose of nonchalance, the war took a terrible toll. Trying to cope with the horrors of the front line, Tanner had invented an ironic but comforting fantasy about himself and the frightened young soldiers who surrounded him: “He would pretend that they were all a suburban family—a mother, a father, two kids,” says Michael. But Tanner finally crumbled under the strain. “He cracked up,” says Michael. “Eventually he had amnesia and became disoriented, speaking to people who were not there. He didn’t know where he was. So this fantasy world became a serious psychiatric infirmity.” Michael says his father received an honorable psychiatric discharge and returned to the States, where he chose New York over Chicago as the place he wanted to live.

He soon met Louise Stickney, a stunning Vassar graduate who had grown up on the Upper East Side in what she described as “Edwardian opulence.” Even in a first encounter at a party, Tanner was memorable. “He was talking about his experiences in the army, and he described his urine sample,” recalled Louise. “It was a gambit I guess most people would have avoided.”

When Tanner met his future in-laws, they were scandalized by his beard, which Louise acknowledged was “an act of flaming defiance” in those days. “They thought it disgraceful; ‘nice’ people simply did not wear beards!” she said. “So my mother finally claimed that it was covering an unsightly war wound.” When they married in 1948, Louise was 26 and Patrick was a year older. Purely to discomfit his parents, Patrick made a point of inviting his father’s longtime mistress to the wedding. “He knew his father would be sleeplessly tossing, wondering if she was coming,” Louise said.

For Louise, who was yearning to escape the strictures of her conservative Social Register family, Tanner represented liberation, along with a welcome dose of irreverence-much of which he directed toward Louise’s devoutly Catholic mother, to whom he enjoyed mailing such postcards as: “Terribly sick in Lourdes.” Raised as a Presbyterian, Tanner had long since become an aggressive atheist. “My father was tremendously blasphemous,” says Michael. “I was being sent to catechism—my mother was doing it for her mother—and he was saying these totally awful things about the Catholic Church and about the Pope. He called Catholics ‘bead fumblers.’ He hated the church—all of them.”

Nor did he confine his jibes to the religious. “Mrs. Stickney had quite a stubble, and as a Christmas present Pat gave her a fine big bottle of Moustache for Men,” recalls his friend Cris Alexander. “The logo was a black moustache. Mrs. Stickney said it was lovely.”

Although Tanner delighted in provoking people, he spent much of his early adulthood building a life that was a model of convention, complete with a nine-to-five job and a nuclear family. While working as promotion director for Foreign Affairs, the official magazine of the Council on Foreign Relations, he ghostwrote other people’s books. In 1953, Crowell published Tanner’s own first novel, Oh, What a Wonderful Wedding (which Tanner said was not his idea of “oh, such a wonderful title”). He wanted to use the pseudonym Benson Hedges, but his publishers balked; when he suggested Virginia Rounds, the brand of cigarettes he smoked, they demurred again. He finally compromised on Virginia Rowans, who was also the author of his next book, House Party, which later inspired the 1966 Phyllis Differ sitcom, The Pruitts of Southampton. “He loved it when some group wanted to have Virginia Rowans come and speak,” recalls Elaine Adam, a close friend who also worked at the Council on Foreign Relations. Although the books had only modest success, their author was praised by The New York Times, which observed that “Miss Rowans writes with a fine feminine realism.”

Then came Auntie Mame, which Tanner dashed off in a frenzied 90-day burst of inspiration. He later claimed that he wrote to every publishing company in the Yellow Pages, starting at the beginning of the alphabet. Nineteen publishers had rejected it and Tanner was down to V when Vanguard Press accepted the manuscript. After picking the name Dennis out of the Manhattan telephone book, he also acquired a new nom de plume.

Auntie Mame was launched with an extra boost from Doubleday Bookstores, which announced that if it wasn’t the funniest book the buyer had ever read, he could have his money back. A huge success, it spent 112 weeks on The New York Times best-seller list and sold more than two million copies. As Auntie Mame became a household name, Tanner’s aunt Marion, an eccentric former actress who lived on Bank Street in Greenwich Village, proved only too happy to claim credit. Until her death in 1985 at the age of 94, she insisted she had been the model for the character. Tanner found this misconception thoroughly irritating. “What enraged him was that people thought he just wrote down everything she did,” explains Michael. “It was fiction.” Michael thinks that Marion probably did serve as an inspiration, but his mother disagreed. “Marion was a very tiresome woman,” Louise said. And besides, her husband had told her who the real Auntie Mame was: “He said, ‘Of course I understand her. I’m her!’ And he pointed to himself.”

With such a red-hot hit on his hands, Tanner had quickly lost his own anonymity. For a few months the literary world buzzed about the real identity of the best-selling new author, but Time magazine soon announced that Tanner was the culprit, describing him as a “socialite” who “regards his writing as an after-hours prank.”

It is true that Tanner didn’t invest his writing with deep meaning. “Never at any time was he burning to write the Great American Novel,” said Louise, who was herself the author of five books, including the novel Miss Bannister’s Girls, which was inspired by her years as a student at Chapin, the Upper East Side girls’ school that was then known as Miss Chapin’s. But Time’s assessment wasn’t quite fair, since Pat Tanner treated even his day job as an after-hours prank. “The Council on Foreign Relations was a very staid, stuffy, Waspy organization where everyone took themselves very seriously,” says Vivian Weaver, who worked for Tanner there. “Then Pat arrived.”

He did his best to entertain the troops. “We’d have lunch in his office and he’d imitate all the fuddy-duddies,” says Elaine Adam. “Or he’d come in like this and say, ‘Who am I?’” She lets her head drop and holds up her arms as if hanging from a cross. Tanner hid in the closet and made faces at Weaver when more dignified personages were passing by; he gave mischievous nicknames to everyone, did pratfalls in the halls, and mixed Manhattans at his desk. “At five o’clock he said, ‘We’re going to have a tasting and vote on different kinds; you have to fill out a form,’” reports Weaver, adding that Tanner once got all the old biddies in the office so bombed she was afraid they wouldn’t make it home.

When Michael was born in 1954, Tanner invited groups of colleagues to come to his house for cocktails and to meet the baby. “He had a huge stuffed monkey called Mr. Murphy, and he wrapped it up in a blanket and handed it to this tasteful lady who was secretary to Hamilton Fish Armstrong, the editor of Foreign Affairs,” recalls Adam. “He said, ‘Here’s the baby—it looks just like me!’ She was dumbfounded.”

But Tanner’s role as provocateur didn’t stop with high jinks. “It was a very lowpaying organization, and he was always worried about the mailroom and the subscription department,” reports Adam. “He went to the executive director and said, ‘These people have to get more money.’” Tanner also made a point of treating his secretary as an equal. “He was way ahead of people,” says Weaver. “If he went out, he’d say, ‘Do you want me to bring you coffee?’ Everyone on the staff loved him.” With typical asperity, Tanner dedicated Auntie Mame to Adam and Weaver, whom he generally referred to as “les girls”: “To the worst manuscript typists in New York.”

Fortunately, Tanner was so charming that his superiors tolerated his antics. Told to get new draperies on a very tight budget, he obliged—but when his boss criticized them, Tanner replied, “Oh, really? Go fuck yourself.” Weaver and Adam were horrified, but Tanner predicted that his phone would ring in 15 minutes with an apology—and he was right.

Cheap office draperies aside, Tanner was much admired for his taste, which was decidedly rococo and ran to ormolu and gilt.

“He had a beautiful ormolu sideboard, and a collection of beautiful clocks, and beautiful tapestries and chandeliers, and a beautiful Regency rolltop desk,” says Weaver. “He would go to England and buy things and have them shipped back.” Tanner redesigned his East 91st Street town house so that the first floor was two stories high, with 20foot ceilings that accommodated the huge tapestries his wife had inherited from her family, and he installed an elevator and a spiral staircase as well. He also commissioned his friend Cris Alexander to paint a mural in the very formal dining room with allegorical figures of the seven arts, one of whom was Tanner himself. (“Patrick called it ‘The Vilification of the Arts,’” says Shaun O’Brien, a former dancer with the New York City Ballet and Alexander’s longtime companion. “Lots of putti flying around holding up masks.”)

But with Michael and his younger sister, Elizabeth, who was born in 1957, Tanner insisted on proper decorum at all times. The first time Weaver and Adam baby-sat for Michael, Adam tried to feed him dinner. Michael, who was then three years old, was aghast: “Oh no, no, no—we have to have drinks first!”

“I said, ‘All right, I’ll give you some apple juice,”’ Adam recalls. “Michael takes me by the hand and says, ‘We have to have our drinks in the living room. Would you like a martini?’”

The Hew York Times rhapsodized of Little Me, "Mr. Dennis's dialogue is so hilarious... that the reader may have to pause to take breath."

“At the age of three, we were schooled in how to make a highball,” explains Elizabeth Tanner, who is known as Betsy. “They drank a lot. Our parents either went out or had people in, but there weren’t a lot of quiet nights at home.”

Good manners were of paramount importance; Michael remembers dutifully going around a room to kiss two or three dozen people in succession. “We were expected to behave like adults at a very early age,” Michael says. “My father had absolute command; when he said to do something, you did it. We were terrified of him.”

Always elegant, formal, and dressed to the nines, Tanner never relaxed his standards, even at home. “It was a perfectly ordered world,” says Betsy, who recently resigned as technical director for the Manhattan Theater Club, where she worked for many years. “His clothes were perfectly ordered; his living circumstances were perfectly ordered.”

But behind the facade of propriety, Tanner’s personal life was in turmoil, and at the height of his success it cracked apart.

Writing had always come easily to Tanner—“I write fast or not at all,” he said—and in 1956 he followed up Auntie Mame with Guestward Ho! and The Loving Couple, the story of a disintegrating marriage told from his-and-hers perspectives. The Pink Hotel was published in 1957 and Around the World with Auntie Mame in 1958. “I’ve dealt with many hundreds of writers in my time, and I think Pat was probably the most facile,” says Julian Muller, the editor in chief of Vanguard Press, who discovered Auntie Mame. “He was so adept. With Pat, I think it was a lark.”

The most elaborate lark of all was Little Me, which purported to be the autobiography of a hilariously vulgar tart named Belle Poitrine. A wicked satire of the selfimportant celebrity autobiography, the book, which was published in 1961, also provides a fascinating glimpse into the final chapter of Tanner’s married life. Lavishly illustrated with photographs by Cris Alexander, it used Tanner’s family and friends to play an elaborate array of characters, with his own town house—complete with tapestries, chandeliers, and the stuffed monkey—serving as a frequent set. “I’d come home from school and find Jeri Archer posing stark naked in my room,” Michael recalls, referring to the luscious blonde actress who played Belle in the photographs. Little Betsy appeared as a child sitting on a potty amid an unruly crowd demonstrating the “intolerable conditions in steerage” on one of Belle’s less luxurious ocean crossings. Louise played Pixie Portnoy, one of Belle’s shallow friends. Tanner himself was the hapless Cedric Roulstoune-Farjeon, a British aristocrat who had the misfortune to become one of Belle’s many ill-fated husbands, despite his obvious (except to Belle) homosexuality. Costumes, jewels, and furs were borrowed from friends who ranged from Rosalind Russell to Kaye Ballard and Dody Goodman.

CONTINUED ON PAGE 195

CONTINUED FROM PAGE 190

The New York Times rhapsodized that Little Me “parodies (sometimes savagely) the vapidity, the insincerity, the vulgarity, the incredible narcissism of some Hollywood personalities,” and continued: “Mr. Dennis lays about him with such prodigality, his dialogue is so hilarious, his pages such a riot of magnificent absurdities interlarded with sly puns, quips, malpropisms [s/c], inside jokes and other verbal buffoonery, that the reader may have to pause to take breath.”

The high spirits attending the creation of Little Me are apparent on its pages, but by the time the show it inspired had arrived on Broadway the following year, Tanner’s life had come unglued.

“He hated the show,” says Michael. “Neil Simon totally changed it and turned it into a vehicle for Sid Caesar.” But that was the least of Tanner’s problems. “A month after Little Me opened on Broadway, my father tried to kill himself,” says Michael. “He had attempted suicide twice as a younger man, but not really seriously. This time it was barbiturates. He tried to drown himself. My mother found him in the bathtub.”

The proximate cause, according to Michael, was his father’s guilt over an affair he had been having with another man. “He’d been cheating on my mother with this costume designer at NBC,” Michael says. After the 1962 suicide attempt, Louise had her husband institutionalized for nine months, during which his treatment included electroshock. None of this was explained to the children. “I came home from school and said, ‘Where’s Dad?’”

Always elegant, formal, and dressed to the nines, Tanner never relaxed his standards, even at home.

Michael recalls. “We were told he was in Florida working on a book. A couple of months later I found a letter from Dad, and being a clever child, I said, ‘How come this postmark is in White Plains?’ When I figured it out, my mother said, ‘Your father’s had something called a nervous breakdown, and he’s in a mental hospital.’”

By this time, sweeping unpleasant realities under the carpet was a wellestablished family tradition. Up until the time of her death, Louise insisted she never knew her husband was gay until his breakdown, despite his penchant for dressing up as Margaret Dumont at the drop of a hat. “I wasn’t aware of it,” she said. “I could hardly believe that homosexuality was coming into our home. That was something that happened to somebody else.”

Her son believes the denial was willful, given the clues she chose to ignore. Tanner, who told his wife what to wear and banned print dresses, which he hated, had surrounded himself with gay friends. “There are pictures of my mother clinking glasses with eight gay men at the table, and she was the only woman,” Michael says dryly. They all had pet names for one another; Cris Alexander and his lover, Shaun O’Brien, were Mr. and Mrs. Musgrove (named after a character O’Brien portrayed in Little Me).

Then there were Tanner’s alter egos; after all, as Michael points out, “he wrote four books under a woman’s name.” Tanner’s predilection for assuming female identities dated back to high school, when he wrote a weekly humor column for the school newspaper called “Judy.” When he started writing books, one of his early ghostwriting names was Evelyn Barkin. And as an enterprising magazine writer named Sarah Brooks, he blithely dashed off a first-person article about being rejected by a sorority for the 1953 college issue of Mademoiselle.

In retrospect, Tanner’s writing style itself may be the most telling; back in the 1950s and early 60s, his sensibility provided a striking contrast to the prevailing culture. “Little Me could never have been written by a totally heterosexual person,” observes Michael. “If my dad has any place in literature, it’s as one of the progenitors of camp.”

Although Tanner managed to write First Lady, another parody in the style of Little Me, while he was in the hospital, the institutionalization finished off his marriage. “He was angry at Louise for committing him,” says Tanner’s niece Sister Joanna Hastings, a Catholic nun. “He didn’t think that was necessary.”

Tanner also felt it was more honorable to leave the marriage than to stay. “He’d say to me, ‘I love Louise—that’s why I can’t live with her. It’s not fair to Louise,’ ” says Sister Joanna, the daughter of Tanner’s half-sister, Barbara.

Louise took it hard. “My mother was absolutely devastated,” says Michael. But the Tanners maintained their usual facade of flawless behavior. When Tanner was finally released from the hospital in 1963, Betsy remembers, her mother told the children that their father was “claustrophobic” and that it was too hard for him to live in the house with so many people, so he was going to move elsewhere. “I think my mother was very sad and disappointed it couldn’t work out, but I never heard a harsh word,” Michael says. “My mother never expressed any anger at him, nor he at her,” adds Betsy.

Tanner set up housekeeping at 930 Fifth Avenue, attended by “this impossibly gay butler named Cecil,” says Michael. One ceiling had a dome on which Tanner asked Cris Alexander to paint a mural of Tanner as a naked and beatific God, floating in an aquamarine sky among cream-colored clouds. By 1965, however, Tanner had wearied of his Manhattan life and taken off for Tangiers to explore the gay expatriate writers’ scene made famous by Paul Bowles and William S. Burroughs. “At this point he was finding it hard to find happiness,” says Michael. “We were going to spend the summer with him in Tangiers, but he hated it. He said, ‘I loathe Tangiers,’ which he described as ‘Canarsie with minarets.’” Instead he whirled through Paris, Madrid, Tunis, Rome, and Cairo, landing finally in Mexico. Louise professed bafflement at this decision as well. “Another mystery, really,” she said blandly. “There were a great many mysteries about this man.”

But Mexico initially seemed to offer a solution to several problems. “He could live cheaply, with a lot of servants,” Michael says. “Dad said, ‘A servant behind every chair’—that was his dream.” Tanner didn’t seem particularly enamored of the indigenous culture. “Patrick was totally urban, and he had not the slightest interest in Getting to Know the Natives, even learning the language, and certainly not reading about the country,” says Katherine Walch, an expatriate friend of Tanner’s in Mexico.

But he retained his characteristic enthusiasm for aesthetic detail. “He had all the servants running around in toreador pants,” said Louise, who visited him there. “He had different colors for different moods and different occasions.”

Tanner described another advantage of his new home in Genius, which had been written while he was still living with Louise and was published in 1962: “The nice thing about Mexico is that ... it is the haven and the heaven of the second-rate,” he wrote. Although Genius sold well, it leaves a bitter aftertaste, in contrast to the essential sunniness of Auntie Mame. Genius is a much darker book whose protagonists—an expatriate American writer and his wife— seem to be either soused or excruciatingly hung over much of the time. The assorted deadbeats and boors who figure in the narrative betrayed Tanner’s contempt for much of his own social circle, as did the various nouveaux riches, their acolytes and predators, and assorted other paragons of tackiness he flayed in Paradise, which was set in Acapulco and published in 1971.

Louise insisted she never knew her husband was gay, despite his penchant for dressing up as Margaret Dumont at the drop of a hat.

And yet because of his fame, he was much sought-after. “He gave a lot of parties and of course everyone wanted to be there,” recalls Walch. Tanner’s book sales may have been slipping back home, but he was still regarded as a prize catch below the border. “In Mexican circles, they think I’m a hot potato,” he told his longtime friend and accountant, Abe Badian, who is now 76.

But even the frenetic activity failed to comfort Tanner. “Those huge parties were just a collection of celebrity seekers, hangerson, and no real friends at all,” says Walch.

And Tanner’s drinking had gradually gotten the better of him. “I remember one night in Mexico when he signed the tablecloth instead of the check, which he thought was amusing, and was sitting under the table dead drunk,” Michael says. “He went through an extremely social period of terrible overdrinking. Alcohol meant eventual oblivion—going out to parties and just losing it. He would take his clothes off in public a lot in Mexico; he was just shitfaced. He was really in bad shape—heading down. There was a lot of surface gaiety, with desperation underneath. In the last year or two in Mexico he was taking his meals on a tray in his room. He was just so hopeless. He seemed to want to obliterate his past.”

Increasingly fearful that he was burned out as a writer, Tanner had also hoped that moving to Mexico would freshen up his work. In 1964 he had published The Joyous Season, a poignant story told from the perspective of a 10-year-old boy whose parents split up. Once again Tanner rewrote life, eliminating the sad parts; at the end of the book, the boy’s parents get back together. But the novel didn’t do well, and Tanner was losing heart. “When Joyous Season didn’t become a hit, I think he saw the beginning of the end of his career,” Michael says. “He was running out of material. I think that weighed very heavily on him.”

Tanner had always been realistic about his own ability, which he never exaggerated. “He said to me, ‘Abe, I’m a man of limited talent. I had a story to tell and I told it. I had some ideas after that and I executed them as best I could. But I’m going out of style,’” says Abe Badian. “He had no great illusions about his standing as an author.”

But at least Tanner was finally owning up to his sexuality—a revelation that came as a total shock to his son, despite such previous clues as the time Tanner arrived for parents’ day at 11-year-old Michael’s private boys’ school, St. David’s, “wearing mink and a pillbox hat,” as Michael put it.

It was another three years before Michael learned the truth. “One night in Mexico, when I was 14, he said, ‘Don’t you know I’m a homosexual?’—like it was obvious,” Michael reports. “I was absolutely bowled over. I was speechless. To me, the fact that everybody was kowtowing to him all those years made him a tower of masculinity. He was so magisterial, ordering people around, with everyone laughing at whatever he said. The thought that he could be gay was as unexpected as if he had said he came from another planet and he wasn’t really a human being.”

Tanner was fairly open about his lifestyle in Mexico, where he lived for a time with a retired U.S. Army officer. “They would drink scotch and milk for breakfast,” says Abe Badian.

But Tanner didn’t raise the subject of his homosexuality with Betsy until she was in college, in the mid-1970s. “That conversation was probably the only time anyone in the family mentioned anything about their personal life,” she says. “It just wasn’t discussed.”

However oblivious his family may have been, Tanner himself had understood his sexual proclivities much earlier. “He said that when he married my mother he thought, Thank God I'll never have to sleep with another man!” says Michael.

But the cure wasn't so simple. When psychoanalysis came into vogue, Tan ner tried that too. “He said he’d been analyzed to try to get over his homosexuality,” recalls Bita Dobo, a friend who worked as a receptionist at the Council on Foreign Relations.

Tanner arrived for parents' day "wearing mink and a pillbox hat."

“I think in some ways he wanted very much to become an American heterosexual white guy, but he wasn’t,” says Michael. “I think he was truly bisexual; he was certainly sexually ambivalent. He felt terrible, terrible guilt; he said, ‘I’ve failed you.’ I do think he was ashamed of it. He would much rather have been straight.”

But happiness eluded Tanner even as a gay man on his own. “I think he couldn’t find love,” says Michael. “That was the only piece of advice he ever gave me: ‘Love,’ as a command. I think his life was without love.” Still searching, Tanner continued to have affairs with women as well as men. “He didn’t know what he was,” says Abe Badian. “He was neither fish nor fowl. He couldn’t make up his own mind what he wanted to be.”

And the culture was passing him by; once celebrated for his witty and up-tothe-minute take on the smart set, Tanner seemed hopelessly out of step with changing times as the counterculture of the 1960s began to dominate the entire society in the 1970s. “He rejected the whole hippie thing,” Michael explains. “He hated my long hair; he called me Veronica Lake. America was becoming less and less formal, and here he was going Edwardian, with his bowler hats and his Savile Row tailoring, dreaming of a footman behind every chair.”

Tanner’s habitual extravagance also led to money troubles. Restless as ever, he kept buying new houses and redoing them; he moved from Mexico City to Acapulco

to Cuernavaca, where he started building a dream house. “By 1970 he had basically spent all his money,” Michael says. “When the house was three-quarters finished he put it on the market. He said, ‘I hate every one of its 50,000 bricks.’ He lost a ton of money on it. That was the nadir. He considered himself written out; he said, ‘I’m as out of fashion as an Empress Eugenie hat, and I’ve written everything twice.’ He was unable to find happiness anywhere.”

In the early 1970s, Tanner tried Texas, where he became co-owner of a Houston art gallery, but he was bored with it even before it failed. Finally, at a fateful crossroads in his life, he made perhaps themost bizarre move of all. In a strange perversion of his own cherished fantasy of having a houseful of servants, he actually became a butler.

“When he dropped out altogether, he was making an escape from the empty, purposeless situation he had got himself into, and wanted to start a new life,” says Walch.

Servitude was hardly his only option; according to Michael, Tanner turned down at least one editing job in New York. But living a modest life as an editor wasn’t as appealing as living in grand style, albeit as someone else’s valet. “The whole butler thing solved several problems,” Michael says. “It was something new; it was funny; it was something he could do well; it was a lark; and he did enjoy it. He was goofing on it. He was very amused that he was better dressed than the people he was serving dinner to.”

His employers had no idea that their majordomo was the famous author of 16 novels. “It was a secret,” says Michael. “He thought that if people found out who he was he’d get fired.” Michael regarded his father’s new identity as “inspired lunacy,” but Louise seemed embarrassed by her husband’s new lifestyle. “I think it upset my mother greatly,” says Betsy, who took her own cue from her father. “He was very cheery about it. He seemed kind of tickled by the whole thing. At the time he was a butler, Michael was a piano tuner, and I was a carpenter. My father thought that was as witty as could be.”

Tanner's incarnation as a butler began in West Palm Beach at the mansion of the Honorable Stanton Griffis, a former ambassador whom Tanner described to his son as “the dearest old fart on earth, with the manners of a pig and the morals of a goat.” When Griffis read his new butler’s letters of recommendation, Tanner reported, “I was a little miffed when he asked, ‘Who is Patrick Dennis?’”

In fact, Patrick Dennis had published his final novel, 3-D, in 1972, and vanished forever. “Patrick Dennis is dead,” Tanner wrote in a letter home. “I killed him with a razor when I hit the Palm Beach airport. The beard is gone and so is the little that was left on top. Now I look like a very old deep-sea turtle. That beard covered a lot of sags and wattles.”

When Griffis died, Tanner accepted a position with Mrs. Clive Runnells in Lake Forest, Illinois, and then moved on to a huge lakeside house in Chicago that was owned by Ray Kroc, the founder of McDonald’s, and his platinum-blonde trophy wife. As a butler, Tanner went by the name of Edwards, although Mrs. Kroc called him “Sweetie.” With each new home, Tanner wrote gleeful letters to his intimates describing his employer’s taste, but the nouveau riche Krocs supplied him with the most delicious details. “When he got to Chicago, he called and said, ‘It’s the most wonderful thing—I finally have solid-gold faucets in my bathtub!”’ reports Cris Alexander.

Was Tanner, despite his denials, on a diabolical mission to collect material for another wickedly funny book? Or did he feel so defeated that he truly saw no alternatives? Were the domestic skills required for a head butler, which he possessed in abundance, the only talents he still had confidence in? Was he acting out some complex psychodrama in which he would do “penance for my profligate life, like going into a Trappist monastery,” as he once remarked to Michael? Did serving as the wellborn butler to the kind of people who had gold bathroom fixtures fulfill some deep-seated need to feel superior to the rich, now that he no longer counted himself among them?

Or was the truth closer to an offhand remark he made in one of his letters to Michael? “I am, of course, stark raving mad,” Tanner wrote.

Not even he seemed to know the answer. “How can I explain it to you when I can’t explain it to myself?” Tanner wrote to Michael.

While “stark raving mad” hardly qualifies as a diagnosis, Michael—who is the medical director of the primarycare clinic at Bellevue Hospital—suspects that his father suffered from manic-depressive illness. “I think he had bipolar disorder,” says Michael. “He’d have periods of frenetic social activity, followed by monklike catatonia. He was very bipolar in every way. He had cycles of great productivity alternating with no productivity. He was very dual: male/female, gregarious/catatonic, and so on.”

Perhaps becoming a butler was a manifestation of that duality; having reveled in a life attended by servants, did Tanner feel some strange desire to trade places and experience things from the other side? Louise preferred to believe he was still thinking like a writer. “He was saving it for a book,” she insisted.

What Tanner might have done with his majordomo days will forever remain a mystery, however. They lasted less than three years, and he never got the chance to turn them into a comic novel. By 1976 he was sick, although at first he didn’t know how sick. His children were astonished to learn that he was moving home to New York—and to Louise. “They were going to get back together,” Michael says. “He had been vomiting and in pain, and he had lost weight, which he was proud of. He said, ‘ur mother’s getting a man with a 30-inch waist!”’

In his time of need, Tanner even put aside his distaste for the prospect of being supported by his wife, who had never divorced him. “Your mother is a very rich woman, and I am a very poor man,” he told Michael. “Not that one cares about tittle-tattle, but what will people say?”

Despite his illness, Tanner insisted that the marital reunion was genuine. “I asked him point-blank if he was having sex with my mother, and he said yes,” Michael reports. By this time, Tanner was traveling light; despite a lifetime of accumulating elaborate possessions, he had divested them as fast as he acquired them. “He never kept anything,” says Michael. “When he returned to New York, he only had two books—Emily Post’s book of etiquette and Vanity Fair.” Betsy adds, “He didn’t even have copies of his own books.”

"Tanner was neither fish nor fowl. He couldn't make up his own mind what he wanted to be."

But no sooner had he arrived home than Tanner learned he had terminal pancreatic cancer. “We went out to Central Park and drank the better half of a bottle of bourbon,” Michael recalls. In spite of the grim news that had precipitated it, the family drew comfort from the fact that after 14 years of separation they were finally together once more. “In an odd way, things were back to normal again,” says Betsy. “It was very bittersweet.”

Despite heavy doses of painkillers, Tanner suffered a great deal; his diary reveals such entries as “Want to die.” But for visitors he dressed himself in crimson silk kimonos (“Red so the blood won’t show,” he said) and gallantly deflected their pity. “He said, ‘I had a marvelous life, I have enjoyed every minute of it, and I don’t want anyone to feel sorry for me,’” says Elaine Adam. Nor did he sentimentalize his own impending demise; he told his dear ones to cremate him, take his ashes, and “just flush ’em down the toilet.”

When the end finally came, the family was watching television. “His last words to me were ‘Turn off that goddamned TV,’” Michael reports.

His final words to the Tanners’ longtime housekeeper, who gave him his shot and asked if there was anything else she could do for him, were: “Yes—for God’s sake, put in your teeth!”

Tanner’s parting remark to his wife was equally characteristic: “You have a spot on your dress, Louise.”

“Those were his last words on earth,” says Cris Alexander. Tanner was 55 years old when he died in his wife’s bed.

Until the end of her life, Louise, who never remarried, maintained that she had no regrets despite the turbulence her husband had left in his wake. “I wouldn’t change anything about having married Patrick, because otherwise I would have been just another little debutante at the cotillion,” she said wistfully. “I’m very glad he rescued me from that life. We had a good time.”

And yet even after all these years, his loved ones still struggle in vain to understand him. Betsy’s only regrets involve “all those millions of questions you never asked,” she says with a sigh.

But Pat Tanner, Patrick Dennis, Virginia Rowans, Lancelot Leopard, Edward Everett III, and Edwards the butler preserved their mysteries to the grave and beyond. Michael thinks his sister summed it up best. “Betsy said he was totally selfinvented,” he concludes.

Last spring, Louise Tanner began complaining of a backache. By the end of April she had been diagnosed with liver cancer that had spread to her spine, and 19 days after her diagnosis she died in her own bed. One of her mottoes had always been “Get it over with.” She did, with admirable dispatch and minimal fuss. Her last words were “Oh, boy.”

Her funeral was held at St. George’s Church on Stuyvesant Square on a blustery wet day in the middle of May. In his eulogy, Michael recalled his mother as a gentle and generous woman, invoking the words of St. Paul’s second letter to the Corinthians: “For God loveth a cheerful giver.” Tall, bearded, and balding, impeccably attired in a somber dark suit, Michael looked so much like Patrick that it was as if his father had returned to mark the occasion— although when the congregation rose to sing a selection from the Christian Life section of the hymnal, Patrick Tanner would doubtless have been rather less respectful than his son was. “Time like an ever rolling stream / Bears all our years away. / They fly, forgotten as a dream / Dies at the opening day,” sang the assembled mourners, snuffling through their tears.

Michael and Betsy Tanner were among the pallbearers who escorted their mother’s casket, draped in purple and crimson satin, on its final journey. Louise was buried with the urn containing her husband’s ashes cradled under her arm.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now