Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

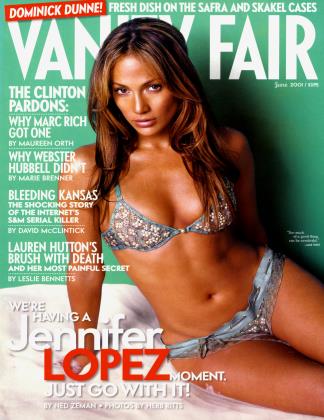

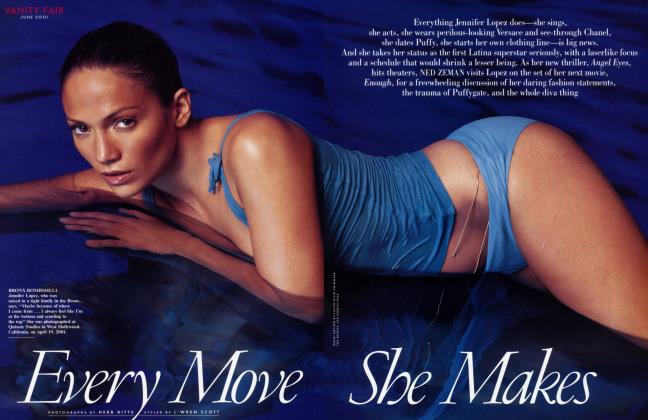

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowLAUREN HUTTON'S CRASH LANDING

LESLIE BENNETTS

First Lauren Hutton discovered her longtime lover had lost her life savings and married another woman. Then she shattered her body in a near-fatal motorcycle accident. So why is America's first supermodel still smiling?

LETTER FROM MIAMI

Lizards skitter along low stone walls and alligators drowse in the sun as Lauren Hutton hobbles along the path, discoursing animatedly on different types of palms. "Those tall, skinny guys are from the Solomon Islands," she says, pointing to a cluster of improbably elongated trees. "And the ones over there with trunks that look like cement— they're Bailey Palms from Cuba. Oooh, look—jade vines! I've only seen these in Jamaica!"

She picks up a handful of fallen jade flowers, succulent boomerangshaped oddities which are an eerily luminous aquamarine. Hooking one into each ear and another in her nose, she flashes a triumphant smile, looking like an African princess freshly adorned for a tribal celebration. That gap-toothed grin is famous all over the world, and two middle-aged women sauntering by suddenly realize who she is—not a difficult assignment, since Hutton has appeared on more than two dozen Vogue covers and in upwards of 50 movies.

"It's wonderful to see you looking so well, after all you've been through," says one. "We hope you're feeling better," adds the other.

The world's first supermodel thanks them graciously and moves on, leaving the flowers in her nose and ears as a child would. Although Hutton has spent half her life roaming the globe to seek out exotic places, today's foray into Miami's Fairchild Tropical Garden is about as close as she will get to the African bush or an Amazon rain forest for the moment. While the garden—a favorite haunt since Hutton was a two-year-old growing up in Florida—contains an impressive array of plant life from all over the world, its lush, well-manicured acres provide only a nostalgic reminder of the wild places where she prefers to spend her time.

But she is in no shape for arduous travel right now, when a short stroll down a garden path requires an orthopedic cane, a great deal of willpower, and a determined effort to ignore the burning pain in her shattered body. Her right leg, broken into pieces—with a section of the tibia pulverized so badly it simply turned to powder—is now held together by titanium rods and screws. Hutton's shin is polka-dotted with electrodes whose wires run into the $8,000 bio-electron stimulator attached to her belt like a beeper. The constant electrical impulses it sends coursing through her leg are supposed to foster bone growth, which is proceeding well enough that Hutton plans to get another one for her right arm, which also suffered compound fractures and is held together with metal. Both the arm and the leg are sliced by long scars that look like zippers.

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

The lacerations on her forehead have healed nicely, however, leaving little trace of the bloody wounds that so alarmed Hutton's friend Jeremy Irons that, even as she lay near death, he demanded the services of a top-notch plastic surgeon to sew her up. The broken ribs and sternum have mended, the punctured lung is working well, and altogether Hutton is in surprisingly good shape for someone who crashed her motorcycle at more than 100 miles an hour, flew 20 feet up into the air, and then hit the ground like a bomb. She was riding in a motorcycle rally near Las Vegas with her regular group of biking pals— Irons, Dennis Hopper, Laurence Fishbume, and Thomas Krens, the director of the Guggenheim Foundation. By the time they got to her she had stopped breathing. Her face had been dragged along the desert ground for 170 feet, and despite the protective visor Irons had insisted she wear that day, her nose and mouth were completely filled with rocks and dirt. If a medic on the scene hadn't acted instantly to unscrew her visor and clear her air passages, Hutton would be dead. As it was, she underwent an eight-hour operation to stitch her body back together and then remained semi-comatose for days, leaving her friends to worry about permanent brain damage. "I was drooling," Hutton reports cheerfully.

That was only five months ago—but today, even under the merciless glare of a brilliant South Florida sun, she is radiant.

At 57, she looks like a woman in her 30s. Tanned to a creamy brown after weeks of lying in a hammock on St. Barts, where she spent the first phase of her recuperation, her face is devoid of wrinkles and even her neck is taut and firm, with nary a sag or a bag in sight. Her deep-set eyes are the color of the Caribbean on a flawless day. Last night we went to a dinner party in Coconut Grove honoring the artist Ed Ruscha, a close friend and the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the Miami Art Museum. Hutton wore no makeup and didn't even comb her caramel-colored hair, which she wears in a wild sun-streaked tangle that looks as if she just came in from the beach. Dressed in white linen shorts and sandals, with a rattan backpack woven by a Malaysian hill tribe as her purse, she still managed to outshine every carefully made-up and expensively dressed woman in the room. "She's 57?" exclaimed the handsome 30-ish doctor who sat next to Hutton at dinner, sounding as shocked as if he had just been informed that she was an extraterrestrial. "She can't be 57!"

Hutton's current glow is even more startling when you consider the other traumas she's endured recently. As terrible as it was, the motorcycle accident damaged only her body, which remains slender and lithe after nearly 40 years of modeling. Before that, however, she had sustained a series of emotional blows that plunged her into a paralyzed depression leavened only by homicidal anger. Since the man Hutton wanted to kill was already deceased, she was left with impotent rage and a grief that seemed insupportable. "I was a murderess for a while," she acknowledges. "I was in serious trouble."

For what Hutton had suffered was not only the loss of the most important person in her life, but also the disappearance of the fortune she had accumulated over her entire working career. Worse still were the kind of shocking revelations that call one's whole history into question. Nearly four years later, she is left with more puzzles than answers, still struggling to accept the fact that the love of her life will never explain the betrayal that nearly destroyed her.

So why does Lauren Hutton seem almost euphoric?

A big storm has passed through South Beach, leaving a gusty wind that whips the clattering palms into constant motion and sends clouds scudding across the sky. Hutton and I are sitting on the terrace of the Tides, the hip hotel, a stone's throw from the Versace mansion on Ocean Drive, that is owned by her longtime friend Chris Blackwell. Picking at her gazpacho, she is telling me about her brush with death last October.

"We were in the Valley of Fire, which is outside Las Vegas," she says. The trip was to promote the new Guggenheim Las Vegas museum, which will open with the exhibition "The Art of the Motorcycle." Riding a red BMW F 650, Hutton had initially set out in a light jacket and a helmet without a full face visor. Dennis Hopper ran back upstairs for a big leather jacket and gave it to her, and when the group paused for a brief rest stop, Jeremy Irons saw that Hutton had tear rivulets running down her face from the relentless wind in her eyes. "He started yelling at me," she says. "He said, 'You've got to change your helmet.' He had an extra helmet, one with a visor, and he made me put it on."

Those generous gestures probably saved her life, and certainly saved her legendary face. During the first leg of the trip, Hutton had gotten separated from her usual group of pals and stuck at the back of the pack. Mistakenly thinking that the riders were leaving the rest stop, she jumped on her bike and tore out of there, anxious to catch up with her friends. "Tom Krens said I was going 105 miles an hour," Hutton says ruefully. "I'm just conjecturing here, because I have a twoand-a-half-week traumatic amnesia, starting just before the accident. My last memory was leaving the rest stop by the side of the road."

Alarmed by her speed, Krens followed her. He later told Hutton that when he rounded a bend, he saw what looked like something out of a Road Runner cartoon. "I was in the air, 20 feet up, on the back of the motorcycle, against the blue sky," Hutton reports. "I must have hit rubble and then gone down in a gutter, so I went straight up in the air. He says I came down, bounced, and went back up, still on the bike. Then the second time I jumped off the bike, which ended up in a thousand pieces. Then somehow I skidded 170 feet, facedown. Thank god the visor on the helmet was down. We were in the middle of the desert, just rocks and sand and rubble. It would have taken my nose, my teeth—I think it would have taken my prefrontal lobes."

When the others caught up to her, Hutton had bones sticking out of her arm and leg and blood pouring down her face. "I think a lot of guys thought I was dead already," she says. "They called for a helicopter and took me to the same trauma hospital as Tupac Shakur. I was on a respirator for quite a while."

Even semi-comatose, Hutton was a tough customer. "At one point they restrained me—tied me to the bed—because I was trying to leave," she says. "Apparently I kept asking if sharks had done this to me. I dive a lot more than I ride, so I guess in my mind a shark bite seemed more likely than a motorcycle crash."

Hutton has actually been riding motorcycles since she was a teenager. During a brief period of attending Sophie Newcomb College in New Orleans and working at night on Bourbon Street, she met Steve McQueen, who was making The Cincinnati Kid and who introduced her to biking. "He was wonderful," she says dreamily. Her second movie was Little Fauss and Big Halsy, which starred Robert Redford. With instructors like McQueen and Redford, it is hardly surprising that Hutton has always spoken about biking in nearsexual terms. "I love the feeling of being a naked egg atop that throbbing steel," she told the Las Vegas Review-Journal the day before her accident. "You feel vulnerable— but so alive."

"He blew up and said, 'I don't want to ever have children. I'm your baby!' That's when I started to unravel."

Nevertheless, for most of her adult life she didn't own a motorcycle. "Bob wouldn't allow me to have one, because he felt they were too dangerous—and I was such a pussy I allowed a man to control what I did," she says, a razor-sharp edge suddenly creeping into her voice.

Bob Williamson was the man who became her first boyfriend when she arrived in New York at age 21, and the man she lived with for the next 20 years. Dominated by him until his death and even beyond, Hutton attributed such power to her lover that she used to refer to him as "Bob God." Short and bespectacled, with Coke-bottle glasses, he seemed an odd match for an internationally famous beauty—but it was Williamson who helped catapult Hutton into the history books as the first genuine supermodel when he guided her into a groundbreaking $200,000-a-year contract with Revlon, for whom Hutton served as the face of the Ultima campaign from 1973 to 1983. That blueprint for an exclusive contract with a major cosmetics company changed the modeling business forever, ensuring great wealth for the supermodels who followed Hutton in the years to come.

Williamson was also the man who showed Hutton the world. The daughter of a Charleston belle and a father who went off to war and never came back, Hutton had had a difficult childhood. Her real father, Lawrence Hutton, had grown up in Oxford, Mississippi, next door to William Faulkner. But Lauren met him only once, when she was 14 months old; he was off serving in World War II when she was born, and he never lived with Lauren's mother, Minnie, again. When Lauren was eight, Minnie married Jack Hall, a former oil wildcatter who had spent time in the South American jungle. They had three more daughters, but they went broke in land speculation and their home life was chaotic with "alcohol and enormous amounts of physical violence and unmitigated disasters," as Lauren later put it. Having been raised in a well-to-do family, Minnie was shamed and appalled by her impoverished adulthood. By the time Lauren was a teenager, she says, "I was basically the only nonalcoholic person over five feet tall in the house. I was raised in the bowl of a volcano, as far as I'm concerned. My mother and Jack were very unhappy. He should have been in some tented camp in the Amazon—he had no business having a family—but my mother was very beautiful, and she could make a man forget what he should be doing."

Lauren (whose original name was Mary Laurence, after her father) grew up in Miami and rural north Tampa as a selfdescribed "swamp skunk," a gawky tomboy who raised and sold earthworms and showed far more interest in bugs and reptiles than in fashion. She escaped her origins as quickly as she could, intending to use New York only as a springboard to the wide world beyond. Her mother and stepfather divorced as soon as she left home, and her real father died at the age of 36, possibly from a heart attack—or maybe it was an old war wound. Lauren never knew for sure.

But who needed them when there was Bob God? In Williamson, Hutton found a mentor whose wanderlust more than matched her own. After she began modeling, they used the money to finance their trips, spending half of each year as far back in the Stone Age as they could get. "We went to Africa every year, to South America, to the Amazon jungle, to the Far East," Hutton says. "Starting in the 1960s, we lived with hunter-gatherer groups that no longer exist."

Her face alight, Hutton can talk for hours about these journeys, describing in intricate detail the social customs of the Pygmies, the differences in hunting rituals between the Masai and the Kikuyu tribes, the varying styles of spears in different regions, how long it takes for a puff adder's bite to kill. She is intimately familiar with the flora and fauna of the wildest places on earth. The geography of Hutton's past is stunningly varied; an anecdote about a dangerous encounter with Mexican hill bandits, defused when Bob shared with them a recipe for making hashish that he had picked up in Lebanon, will follow a story about falling off the roof of a Land Rover into the path of a charging rhino in the Serengeti, only to have her life saved by—who else—Bob God. The place-names roll by like an endless river, conjuring up a dizzying succession of exotic images— Zanzibar, Mauritius, Mount Kilimanjaro, Uganda and Ethiopia and Tanzania, Somalia and Kenya, Java and Bali, Burma and Sumatra and Thailand, Peru and Ecuador and Venezuela and Colombia. Hutton has wrestled alligators and gone dogsledding in the Arctic, eaten termites and cuddled up to tarantulas; you have the feeling that she could talk for days and never run out of stories, or places, or memories.

In retrospect, Hutton suspects that her fascination with African tribes was rooted, at least partly, in subconscious memories of her earliest childhood, when she and her divorced mother were living in her grandparents' home. "The people who really loved me when I was a baby were the black people who worked in my grandmother's house and my godparents' house," she says. "Those are the people I truly felt something with."

The underlying reasons for Hutton's subservience to Bob are even easier to parse. Never having had a real father, she was a sitting duck for a controlling older man who wanted to run her life. "Bob was an enormous father figure," she says. "I was truly besotted by Bob. He was a really extraordinary guy. He knew so much about so many things. The third time I met him, he started talking about Cajuns. I knew quite a lot about Cajuns, and he knew more than I knew. He had a photographic memory; he could recite pages of Finnegans Wake to you. He knew all about Goliath beetles and different kinds of scorpions and all the things I loved. He knew way more than I knew about bugs I had been collecting since I was a child. He knew about every type of beetle and weevil, and that was my specialty. He knew about all these things that I knew smatterings of, and that other people didn't even know existed. And he was a spectacular storyteller. It took me about two weeks, and I was a goner."

But she recognizes now that even in the early, happy years with him, she was selfdeluded. "I created a fantasy world for myself, to not know who he actually was and what he was actually doing," she says. "I don't think I'm particularly bright, but I have enormous common sense—and I parked all my common sense with Bob."

They lived together for 20 years, although Hutton retained such bitter memories of her childhood that she never wanted to marry. Working in far-flung places, Hutton was constantly besieged by other men who, frustrated in their attempts to seduce her, couldn't understand how Bob managed to maintain his Svengali-like influence, even at long distance. "They would say, 'How does he do it by remote control?'" Hutton recalls with an impish smile.

Bob also controlled their finances. Completely in his thrall, Hutton faithfully turned over all her money, which he was allegedly investing. Indeed, this appeared to have become his career; he had quit his job at a textbook-publishing house soon after he met Hutton and moved in with her. From then on he presented himself as a market player. "He never had a job again for the rest of his life," says Hutton. "I believed we were in business together. I was making a lot of money, and we spent very little in those years; it was all being saved 'for our future.' We were saving for a family. We lived in a $400-a-month rent-controlled apartment, I never spent money on clothes, and with most of the trips, I got paid to go there; I'd take a job and then we'd just go off afterward. We never had a house; we never owned an apartment; we never had a car. I was so concerned about not doing what I had seen done in my family that I put off having children. I thought I'd do it around 40."

When Hutton was 41, she told Bob she was ready. "He blew up and said, 'I don't want to ever have children. I'm your baby!'" she reports. "That's when I started to unravel. And then I went into menopause at 45 or 46," an experience that turned her into a passionate advocate and spokesperson for hormone-replacement therapy.

After that, Hutton began trying to live apart from Bob, but couldn't seem to make a real break. Even when she was living on the West Coast with another man, she says, "I kept going off to Africa with Bob. How could I not? I was being asked to go off and live with !Kung bushmen. He had taught me everything. I had grown up with him. When I was in New York, I had dinner with him every night. I couldn't live with him, and I couldn't live without him. The way I dealt with it was doing five movies a year."

As she got older, Hutton had also begun asking Bob to show her some financial records and explain where her money was and how it was doing. "He wouldn't show me," she says. "He had a lot of reasons why. The biggest one was 'What's the matter—don't you trust me? It will just confuse you.' I used to sign entire checkbooks for Bob; he would pay everything. I never paid a bill till I was 47. For the first 10 years I did trust him, but it just seemed odd. I was starting to grow up, and it didn't make sense. By the time I was in my middle 30s, I no longer wanted a master; I wanted an equal. But it still never occurred to me that he was taking the money, or that he was losing it. He could outtalk the Devil. He said he was investing in the stock market. He told me I was in blue chips, but with his own money he would put himself in 'fliers.' It turned out there was no such thing as the blue chips. He either lost the money or put it offshore—I have no idea— and what was left, he left to two girls, one of whom he married a few days before he died. I call her 'the five-day wife.'"

His death at age 61 caught her completely unprepared: "He told me he had an ulcer, but he was still very young. Bob was superhuman, so it never occurred to me that he was dying. He was the live-est person I ever met."

She was in Hong Kong on a scubadiving trip when she heard the news. Although Bob's new wife attributed the cause of death to cancer, Hutton believes it was "emphysema and alcohol. It took him a very long time to kill himself." All the same, his death remains shrouded in an element of mystery—just like that of Lauren's father.

"When I got the word, I literally fell down," she says. It took her two weeks to get from Hong Kong back to New York; unable to function, she kept checking into airport hotels and going to pieces for days at a time. "I stopped everywhere," she says. "I could barely walk. I would lock the door and stay for days, just crying." She finally made it as far as Los Angeles, whereupon friends flew out from New York to retrieve her and put her to bed.

"For the last three years, I would have ripped open the root-cellar gates to hell, just to smack him a few times."

When she learned that Bob had married a 33-year-old model right before he died, and that he had left what money he had— around $2 million—to his new wife and another woman, she entered a surreal twilight zone of disbelief. It appeared that her entire life's earnings had vanished, a sum that Hutton estimates would now be $30 million to $35 million if it had been deposited at a minimal interest rate in a bank. "All my money from those years is gone," says Hutton.

It was actually 10 days before he died that Bob married Lauren Helm, who had been involved with him for nine years. Their deathbed ceremony was a practical matter, according to Helm, whose original name was Laura. "He wanted to leave me money to pay for my going to medical school," she says. "I don't think he realized Lauren would be so hurt. I had wanted him to tell her he was dying, but he didn't tell his mother, his brother, anybody. He said, 'I haven't got the energy right now to make them feel better about my dying.' It was embarrassing to him. He was an incredibly proud, private person."

Helm doesn't believe Bob did anything underhanded with Hutton's earnings. "I think her $30 million is an overestimation of the amount of money she had," says Helm. "Whether he handled it perfectly, I don't know. I know he lost money in the stock market. But I doubt very much that there's $10 million sitting in some Swiss bank account. That's not his personality. I obviously don't believe Bob was a crook."

He was, however, a ladies' man. Since Bob's death, Hutton has tracked down enough of his former girlfriends to realize that he had always cheated on her. "I didn't know—I wouldn't face it—but it had been going on the whole time," she says. A phone conversation with one former inamorata actually cleared up a mystery that Hutton had long wondered about: the origin of the persistent rumor that she is gay. "Apparently one of his girlfriends confronted him about me—he had never told her that we lived together—and he said, 'I'm bearding for her. She's a lesbian, and she's going with Julie Christie.'" Hutton shakes her head in disgust. "I had never even met Julie Christie."

Ever since Bob's death, she has struggled as much to explain her own passive acquiescence all those years as to understand his apparent malevolence. "People who didn't know Bob were quite incredulous about how I could be so foolish in so many ways," she says. "But I had a shattered childhood, with no father, and I think I had a shattered ego. Bob was the adult for us. I turned everything over to him, and I was finally able to have a childhood. Because I had been the responsible adult from the age of 10, I wanted a childhood, and Bob took care of all things adult, like where we were going and what happened to the money. I liked being a child, and I thought I had the greatest parent in the world. And in some ways, I did—for what I wanted. I wanted a daddy so badly that nothing else mattered."

Even Bob's widow is astonished at the trust Hutton placed in him. "I think her expectations of Bob were utterly ridiculous," says Helm. "He was a well-educated man, but she had made him into this god."

Hutton is willing to reveal her humiliation now in hopes that it will serve as a cautionary tale. "I don't want this to happen to other women," she says fiercely. "This is how it happens to women: 'Daddy is taking care of it.' I'd like to get women to understand that what you're doing in a situation like this is not love. You're fulfilling some sort of sad need. But you can't really love anybody until you figure out how to love and protect yourself. If you just close your eyes, chances are you're going to get nailed."

Even after all this time, he comes to her in dreams. Sometimes she wonders whether he is really gone. Could he have staged his death and taken off for parts unknown, armed with her fortune? "In one dream I had, I saw him and he was alive," Hutton confesses. "I said, 'You faked it, didn't you!' He gave me his very beautiful, characteristic grin and said, 'Yeah.'"

And what would she do if she saw him now? "I'd probably give him a tremendous hug, and then I'd start crying," she says. "And then I'd smack the living shit out of him. And then I'd tie him up and tape his mouth, because it's like having a large spitting cobra on your hands. And then maybe I'd get him to a good shrink, although a good shrink probably wouldn't take him with his mouth taped and his arms and legs tied."

But most of the time she believes he is dead, and she is trying to accept the fact that she will never fully understand why he did whatever he did. "I think he O.J.'d it," she muses. "I think he was able to keep things in compartments. I think there was the good Bob and the bad Bob, and the bad Bob became more dominant after he got into alcohol, which was probably not until about year eight for us."

FOR DETAILS, SEE CREDITS PAGE

Although she recognizes the possibility that he hid the money somewhere, and that her fortune will molder forever in some anonymous Swiss bank account, her best guess now is that he simply lost it. Her rage has been titanic—"For the last three years, I would have ripped open the root-cellar gates to hell, just to smack him a few times," she says—but it is slowly subsiding. Indeed, she has achieved a remarkable degree of equanimity about the traumas she has endured. She even learned some crucial lessons from her motorcycle crash.

The most important fact was that more than a dozen loved ones immediately flew to her bedside as she lay near death. "Tom Krens called all my friends—Francesco Clemente, Ed Ruscha, Brice and Helen Marden," she says. "What was great about the accident, for me as someone who has had a problem with love, was that I saw very clearly that my friends loved me, and that I have a very big, rich, strong family. They really saved my life. I think somehow they kept my mind here on earth. I'm quite sure I would not have come back otherwise."

Delirious on morphine, Hutton kept murmuring, "I have a family. I have a family."

"So I must not have felt I had a present family," she concludes. "Since the accident, most of the time I'm more happy, more peaceful, more content than I've been in my life. I'm much more sane since this happened. Every second I've got is extra time; it's after death. I hear myself say, 'After I died ... ' or 'When I was killed ... '"

And she's still here. These days Hutton lives in a loft in NoHo and keeps a small cabin in New Mexico, but she is itching to hit the road again. For the moment, the wanderlust will have to wait, but at least she has stabilized her financial situation and secured her future. "I worked like a banshee for the last seven years, and salted an awful lot of it away," she says with pride. "Because I've lived modestly, I really don't have to work."

Although she has not been in love since Bob died, she's hoping that one day she will be again. But she recognizes that her requirements are tough. "I'm a real specialty act," she says with a sigh. "I need a guy who knows where Molepolole is." (For the record, it's a town in Botswana best known as a jumping-off point for journeys across the Kalahari Desert.)

But in the meantime, the happy memories of Bob have finally started to outweigh the horrors once more. "I remember the good days," she says softly. "He had a great laugh."

And if she had it all to do over again? Hutton gazes off into the far distance, past the snowy white beach and the blue waters to the unknown beyond. "I came to New York to see the world, and I still have met no one who could show me the world better than he did," she says. "I've been to see all the wonders. We had so many adventures. If I had a chance, I'd do it all again in a second. It was worth $30 million."

Then a sly smile steals across her face. "But this time I'd only give him half the money."

All those revenge fantasies seem to have served their purpose. Able to move on at last, she now suspects that she wouldn't retaliate after all. "Maybe I wouldn't do any of those things if I saw Bob," she says. "Above all, I don't want to be bitter. And I loved him. Maybe I'd just ask where we were going next."

She flashes that dazzling grin. "I'm packed," she says. "I'm always packed."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now