Sign In to Your Account

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join NowKING OF KINGS

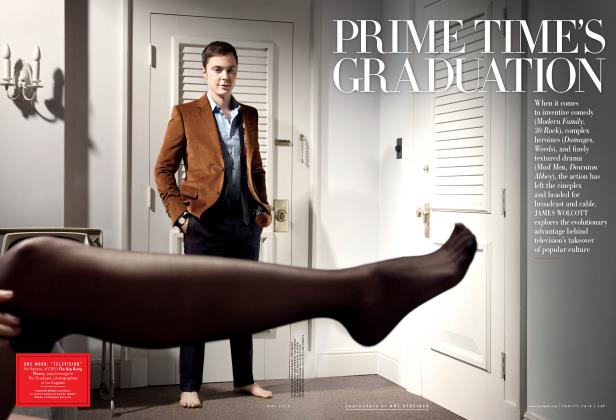

JAMES WOLCOTT

If Elvis lives-and he does, in recent books and movies and the spate of critical examination sure to accompany next year’s silver anniversary of his death-it’s because we still don’t know what to make of his druggy, bloated ruin. Was he a cultural martyr or a junkie cop-out?

Like flying-saucer visits and Roseanne marital spats, Elvis sightings have tinkled out in the supermarket tabloids to near zero. His pale specter is seldom spotted prowling the aisles of all-night convenience stores, or filling up the gas tank on the outskirts of nowhere. Elvis may no longer be making cameo appearances in the Twilight Zone, but his mystique—his semi-holy corona—retains its lasting hair-spray hold. In books, movies, advertising, and the image bank of postmodernism, he’s as in demand as ever. Just this year two novels starring Elvis hit hardcovers: Elvis in the Morning (Harcourt Brace), a bittersweet valentine embroidered by William F. Buck_ ley Jr., and Elvis and Nixon (Crown), by Jonathan Lowy, a farcical docudrama about the flipped-out episode when Elvis met with Nixon in the Oval Of! fice, imploring the president to award him a special drug-enforcement badge so that he could hop in the Batmobile and bust drug dealers—Elvis, Superstar Supemarc! Next year will bring an even bigger rollout of Elvisiana: 2002 marks the silver anniversary of Presley’s death at his Graceland estate, a bonanza opportunity for a commemorative orgy of musical repackagings, souvenir merchandise (already announced: a line of Elviswear, for those who want that real-gone look), and high-end editorial pondering. I predict a spate of intellectual groin-pulls in the “Arts and Leisure” pages of The New York Times.

Born in Mississippi on January 8, 1935, Elvis Presley was the surviving member of what his mother, Gladys, believed were identical twins: brother Jessie Garon was stillborn. She spoke so obsessively of the dead brother that he became an imaginary companion in Elvis’s childhood mind—“a phantom double, a secret sharer, a veritable Doppelganger,” to quote one biographer. Jessie Garon’s absent presence contributed to an aching feeling of separation and sense of incompletion in Elvis, and provided rich acreage to future psychohistorians. Also absent from Elvis’s wonder years was his father, Vernon, a splinter of a man who served time in prison and worked at a defense plant during the war, leaving Elvis alone with his mother, who spoiled him like crazy, and why not?— he was all she had.

On a sweltering July day in 1954, a 19year-old Elvis walks into Sam Phillips’s Sun Records studio in Memphis to cut a few sides. Elvis’s tame musical taste vacillates between gospel standards and the oleaginous hits of Dean Martin, but his look—lacquered ducktail hair and a cockatoo wardrobe with tropical colorssmashes the sound barrier for him. After butchering a ballad called “I Love You Because” (from “Love Me Tender” to “Can’t Help Falling in Love,” Elvis’s droopy crooning would always evoke the kitsch of black-velvet paintings), he messes around with “That’s All Right” and in the course of a few minutes gives popular music a bolt of white lightning that leaves the first half of the century clipping coupons and eating dust. Welcome to the jet age, baby! Cupped in an oval of slap-back reverb (Sam Phillips’s production trademark), the plunky guitars and clockwork drumming in the Sun sessions carry a familiar twang of front-porch jam sessions, but the selfparodying swagger of Elvis’s vocalizing— his quick, jovial, darting command of lyrics and rhythmic inflections, as if he were capturing all sides of a song at once— kisses the square world good-bye with the same cocky, self-parodying nonchalance Marlon Brando brought to The Wild One, where even the set of his motorcycle cap is witty. Elvis and Brando are mercury balls whose moves and mannerisms seem a beat ahead of onlookers’ thoughts, anticipating their responses, eluding easy categorization, and making detractors look as stiff and programmed as IBM punch cards.

The masterpiece mentality that prevails in cultural appreciation stipulates that lasting works are the results of serious conception, overarching design, Flaubertian dedication to fusspot detail, and vast expenditures of hope, energy, and resources. This leaves out an entire factory-floor tradition of American ingenuity where makedo problem-solving, experimental tinkering within tight budget limits, and joshing teamwork produced the films of Howard Hawks, the glory days of Marvel Comics, and the golden age of live TV. The tracks recorded over two years at Sun Records and preserved, outtakes and all, on The Complete Sun Sessions (RCA) have a thick grain, metallic gleam, and playful, mongrel spirit that seem to belong as much to the garage as to the recording studio. These are songs built for joyriding.

When a popular Memphis D.J. named Dewey Phillips repeatedly plays Elvis’s first single, “That’s All Right,” on his radio show, the listener response is electric. Soon after, Elvis performs his first live show, and, unlike all the white male singers who have come before, he doesn’t use the bottom half of his body simply to support the top half; earning him the nickname “Elvis the Pelvis,” his jumping-bean gyrations and pistoning whip female fans to squeals of hysteria that haven’t been heard since bobby-soxers held fainting spells in front of Frank Sinatra. There’s no governing Elvis’s hips now. They’ve cracked the combination lock of Puritan repression. His exploits scroll across the consciousness of the nation like tickertape news: ELVIS SNUBBED ON GRAND OL’ OPRY . . . ELVIS WINS NEW HEARTS ON LOUISIANA HAYRIDE . . . MANAGER COLONEL TOM PARKER TAKES SINGER UNDER VULTURE WING . . . ELVIS HITS BIG WITH “HEARTBREAK HOTEL” . . . HUMILIATED ELVIS SINGS “HOUND DOG” TO BASSET HOUND ON STEVE ALLEN’S TONIGHT SHOW . . . ELVIS PERFORMS ON ED SULLIVAN PHOTOGRAPHED ABOVE THE WAIST, STUNT WATCHED BY OVER 80 PERCENT OF TV AUDIENCE . . . ELVIS TACKLES CELLULOID IN FIRST PIC, LOVE ME TENDER . . . TIME MAGAZINE COMPARES ELVIS SCREEN IMAGE TO SAUSAGE . . . ELVIS DATES BEVY OF STARLETS ... tumult applause movie posters magazine covers newspaper editorials white panties pomade pink Cadillacs!

Overwhelmed by fortune, object of fan hysteria, attacked by print-media prisses, and satirized everywhere (“Pelvis chokes worried moan of the torch song, ‘I Almost Found My Mind,’” runs a cartoon caption in Mad magazine), Elvis seeks refuge from the world’s gimme-gimme demands by buying a porticoed mansion in Memphis called Graceland. It becomes more than a home; it evolves into a hillbillydeluxe court, a royal playpen where Elvis’s every word and whim are law. Outside, pandemonium and the prying photographers and reporters; inside, privacy and control maintained by a smooth-running machine staffed by a flying wedge of good of boys called “the Guys” or “the Memphis Mafia.” Their proud emblem is TCB with a lightning bolt, meaning, “Taking Care of Business—in a flash!” (When he was a child Elvis’s comic-book hero was Captain Marvel, whose lightning-bolt insignia and costume Elvis copied and Liberace’d up into a studded white jumpsuit and cape.) Within this deep-fried Camelot, the King of Rock ’n’ Roll is pampered like a prince. When His Highness is displeased, darkness falls across Elvisworld until the next cheeseburger is summoned. He and his flunkies devour junk food like teenagers, take speed to keep themselves buzzing, race slot cars, play pranks, wage squirtgun battles, cherry-pick girls for the royal bedchamber (Elvis prefers virgins), spy on women through a two-way mirror, and keep a pet chimp named Scatter that Elvis’s gang teaches to drink in order to provoke even more uproarious mischief, such as flipping up women’s skirts. Not exactly a sparkling night at Noel Coward’s.

The year of Bobby Kennedy's and Martin Luther King's assassinations finds Elvis at the midget depths of relevance. He needs to fight his way back to center court.

In retrospect, everyone agrees that Elvis’s stint in the army in 1958 was a debacle that put his career on hold, wrenched him from his doting mother, who died as he was due to leave for Germany (the defining moment in Elvis’s adult life), and got him even more hopped up on speed, which soldiers would take so they could stay awake on duty. It was while overseas that Elvis also met a nymphet named Priscilla Beaulieu, whom he would make the mistake of marrying in 1967 (a mistake because Elvis never wanted to behave as anything but a bachelor). The compound loss of mother, career momentum, and contact with his audience took the fight out of him. The Elvis who re-enters show business as a civilian in 1960 is a shaky pod-person, a tan eunuch sentenced by Colonel Parker to star in a series of innocuous movies spit out like chewed gum. Debate still rages in monasteries and laundry rooms across the land over which Elvis film leaves the biggest blotch. Is it Tickle Me, It Happened at the World’s Fair, or Kissin Cousins, in which Elvis played twins, thus splitting himself into two bad actors? Individual eek factors aside, the post-army films together amount to a long spool of indignity. The albums also dragged bottom. John Lennon’s epitaph still holds true: “Elvis died the day he went into the army.”

Dead, he refuses to stay buried, resurrecting his career and legend not once but twice. The first resurrection occurs in 1968 with the broadcast of Singer Presents Elvis on NBC. (So called because the Singer corporation was the sponsor.) Nineteen sixty-eight, the year of Bobby Kennedy’s and Martin Luther King’s assassinations and the riots at the Democratic convention in Chicago, finds Elvis at the midget depths of musical and social relevance. While the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, the Who, and Bob Dylan fire electrons with ringing guitars and flaying lyrics, Elvis’s records continue to drip sap. He needs to fight his way back to center court, prove he still has the chops. The broadcast (available on videotape and DVD) proves a triumph as Elvis rises to the challenge after much trepidation and belts home his old hits with jubilant conviction. The musical arrangements of Billy Goldenberg and Bones Howe update Elvis’s sound, unclogging all the cotton candy from his soundtrack albums and releasing a fat and sassy blast of Memphis soul. Elvis now has a brass section behind him that can send him into battle.

The success of the Singer special leads to the second resurrection, Elvis’s conquering of Las Vegas in the summer of 1969. Having made a mortifying debut in Vegas early in his career, when he was billed as “The Atomic Powered Singer,” Elvis has personal incentive to put on a show that’ll blow the toupees off those high rollers and their hideous wives. Where a swiveler like singer Tom Jones, pelted with panties and room keys from delirious female fans in his act at the Flamingo, slings his moneymaker around with abandon, Elvis disciplines and choreographs his erotic charade for maximum delayed-gratification payoff, trading in his black leather for a karate wardrobe (and, later, the famous Captain Marvel jumpsuit) and letting the music climb a ladder of arousal before he presides over the climax, striking a series of victorious poses drawn from martial arts and Greek myth. No longer consumed by the Dionysian energies of his youth, he’s now in command of those energies, unleashing them like neon thunderbolts.

Elvis does more than dazzle the beehive brigade. He reawakens the ardor of jaded rock writers who had relegated him to the dinosaur bog. Elvis and Colonel Parker never catered to critics in the past— they didn’t have to—but this time furry members of the New York pop-culture intelligentsia were flown into town on Kirk Kerkorian’s private jet to witness Elvis’s Hilton debut. From their typewriters issues the good word that this show-business miracle is no desert mirage. (A judgment recently seconded by Marc Weingarten of Slate, extolling RCA’s 2001 release of Elvis Live in Las Vegas, a four-disc set that showcases the thunderation of Elvis in all his spangled vainglory, chugging through “Suspicious Minds,” scaling the corny heights of “The Impossible Dream,” and performing Marty Robbins’s “You Gave Me a Mountain” with disarming intimacy.)

As thrilling and inspirational as the Singer special and the Vegas comeback are, they resound as bombastic feats, not artistic breakthroughs. Personally buoyed, Elvis doesn’t capitalize by digging deeper into himself or striking out in new directions; he simply settles into a more flamboyant rut, playing regular Vegas engagements—taking the stage to the apocalyptic strains of Richard Strauss’s “Also Sprach Zarathustra”—until they too become a joyless, unchallenging grind. In his sealed-off domain, Elvis maintains an illusion of mastery—an illusion because all the cool toys in the catalogue and bouffant starlets on the studio lot can’t keep the demons of doubt, insecurity, and low self-esteem from nesting in his night brain. In the mid-60s, searching for answers like so many wayfarers in this fallen sphere, Elvis latched on to a hairdresser-slash-mystic guru named Larry Geller, who gave him copies of occult-bookstore classics such as Autobiography of a Yogi and The Impersonal Life to aid him in his spiritual quest. Elvis’s mind opens like a millionpetaled Blakean blossom. He and Geller mull over these texts and others for hours, stupefying and annoying everyone else within listening range. The Guys want to play football or corral some nookie, and here’s the boss giving himself eyestrain searching for the meaning of life. Elvis’s Technicolor epiphany comes when he and his entourage are driving through Arizona and he spots a cloud with the face of Joseph Stalin. Instead of being freaked by a cloud bearing a dictator’s likeness, he has the bus pull over and welcomes this vision as a calling card from Christ. In his euphoria Elvis believes he has finally broken through to a higher plane, but it will prove to be a trampoline, his manic highs followed by depressive lows.

Meanwhile, everything around him unwinds. Elvis, who finds intimate relations with mothers abhorrent, recoils from having sex with Priscilla after she gives birth to their daughter, Lisa Marie, in 1968; starved for attention and exasperated by her husband’s infidelities, Priscilla begins an affair with a karate instructor, an act of retaliation that knees Elvis right where it hurts, in his male pride—the karate instructor being the true martial artist Elvis only pretends to be. (Elvis and Priscilla begin divorce proceedings in 1972.) Elvis’s drug intake and Colonel Parker’s gambling debts begin to skyrocket in unison, as if the two of them were in unconscious competition to see who can flame out first. Elvis wins and, by winning, loses. Morose, overweight, zonked, physically feeble (he needs to be helped to and from the bathroom), and emotionally infantilized, Elvis turns his bedroom at Graceland into an air-conditioned womb. In the end, the tension between what the world expects and what he has left to give, between the image stamped in everyone’s mind and the flabby face he sees in the mirror, between the extravagance of his lifestyle and the poverty of his inner resources, becomes unbearable—he cracks. On August 16, 1977, Elvis Presley is found facedown on the bathroom carpet, his pajamas around his ankles, the body cold. The autopsy reveals that the cause of death was polypharmacy: 14 drugs were detected in his system, a jumbo cocktail mix that included large amounts of codeine and methaqualone (quaaludes). He had turned his body into a toxic blender.

Like Jesus’s death, Elvis’s inspired rival gospels. The rough draft of the profane tabloid version appeared in his lifetime and helped feed his paranoid spiral—a bombshell book, Elvis: What Happened?, by Steve Dunleavy, who took the tattling of three disgruntled members of the Memphis Mafia and whipped it into a frenzy. This expose provided the first inside peek at Elvis’s drug use, sexual peccadilloes, and violent tantrums (shooting out a TV screen because he couldn’t stomach looking at Robert Goulet—understandable, perhaps). Its debunkery helped provide the dirt and ammo for Elvis, Albert Goldman’s biography, published in 1981, a best-seller that dove even deeper into the dirty hamper and medicine cabinet. It portrayed Elvis in his final days as a Baby Huey in soiled diapers, a junkie lost in a stupor, his pasty skin dotted like an old newspaper photo from years of needle abuse. To Goldman, a Jewish hipster and jazz buff whose zap-gun journalism mimicked the velocity and shock tactics of sick humorists such as Philip Roth and Lenny Bruce, Elvis’s slow fade wasn’t something to sentimentalize. It was a slapstick farce, a tacky spectacle. A desolate monarch surrounded by the shattered pieces of his dreams, Elvis wasn’t Charles Foster Kane sleepwalking through Xanadu—his follies lacked a grand Gothic dimension. Graceland was closer to Howdy Doodyland.

The book, which in later years would serve as People’s Exhibit No. 1 in the sordid new genre of “bio-pom,” provoked an outcry and backlash that in turn inspired a major reclamation project to retrieve Elvis’s reputation from the gutter and restore the luster to his gold lame suit. The fundamental text of this official gospel is Peter Guralnick’s two-part opus, Last Train to Memphis and Careless Love. Conscientious, fairminded, panoramic in scope, monumental in size, a procession march through the past scored to a grave sense of mission, this is a biography written in presidential prose, full of sonorous trumpet notes. In the preface to the second volume, Guralnick intones, “The story of Elvis’ inexorable decline ... is neither a simple nor a monolithic one, and it may have no greater moral than the story of Job or Sophocles’s Oedipus Rex: Count no man lucky until he has reached his journey’s end.”

Guralnick’s biography was greeted by critics with a rapture and gratitude born of relief. Typical was Terrence Rafferty’s review of the second volume in GQ: “Guralnick writes with such profound sympathy for his subject that Elvis’ fate, though excruciating to read about [several times Terry had to set aside his sandwich], isn’t shocking, as it was, for example, in Albert Goldman’s loathsome 1981 biography. Guralnick, working with the same basic material, shows us a terribly unhappy and frustrated man. I know which version I believe.” The critics believed what they wanted to believe because their faith had been restored.

Elvis may have betrayed his natural talent, but we've embraced that betrayal, preferring the plastic facsimile he became to the breaking news he once was.

The gulf between the sacred and profane gospels of Elvis goes deeper than a dispute over sympathetic tone or factuality. It’s a matter of responsibility, the content of one’s character. To Guralnick and his fellow scribes, Elvis’s downfall was the fulfillment and conclusion of a tragic destiny—the “inexorable” splat of a life that soared too high too soon too fast. To Goldman, however, Elvis’s destruction wasn’t the end product of forces beyond his control; it was rooted in a protracted failure of nerve, a permanent arrested development that he stubbornly defended and indulged in order to avoid making hard adult decisions. Elvis Presley was an astonishing man-child who never became a man—a mama’s boy who needed to be babied to the bitter end. Where the sacred gospel elevates Elvis into a handy, sentimental, all-purpose martyr symbol, the alternative version at least grants him the agency of choosing the life he led and the death he met. In a 1991 follow-up book, Elvis: The Last 24 Hours, Goldman goes even further, asserting that Elvis’s death wasn’t due to heart failure or accidental overdose. It was his most volitional act of all: suicide. He took what Hemingway called the Big Out.

Elvis had three megadoses of barbiturates, tranquilizers, and painkillers (such as Demerol) administered each day, which he called “attacks.” Instead of spacing them out at the usual intervals that August afternoon, Elvis—despondent, betrayed by his former bodyguards, unable to face the prospect of touring again looking so tremendously out of shape, lacking the will to persevere, making veiled references to suicide to those around him— hoarded his stash and gave himself an intentional overdose. He did not slip peacefully into easeful death. The state of his body revealed signs of paroxysm.

Unlike Elvis, Elvis: The Last 24 Hours isn’t a mocking graveyard jig. It’s a concise, subdued reconstruction, ironic in spots (Elvis consoles a man whose wife had left him by hanging a protective arm around him, leading him to the window, and offering these words of comfort: “Son, just remember this: somewhere out there is an eighteen-year-old piece of ass just waiting for you”). Goldman saves his most damning words for the end, writing in the afterword:

What is most lacking in the life of an Elvis Presley is precisely what you see on every page of the biography of a Charlie Parker— a passionate commitment to art, to selfexpression, to the struggle to put into music the hard-earned wisdom of a life that through its very extravagance revealed many truths about the human condition. Elvis Presley never stood for anything. He made no sacrifices, fought no battles, suffered no martyrdom, never raised a finger to struggle on behalf of what he believed or claimed to believe.

His suicide, therefore, was his final act of cowardice, the ultimate cave-in of weak character.

Intellectually, I agree with Goldman’s indictment of Elvis’s shanking of his aspirations; emotionally, I’ve come to feel pity and forgiveness. “An artist is his own fault,” to quote John O’Hara, and Elvis was his. In a culture less morbidly obsessed with celebrity, less inflated with myth-mongering and critical hyperbole, his flaws and accomplishments would be allowed to rise, sink, and find their proper level on a human scale. Elvis may have betrayed his natural talent and turned into a parade float, but we’ve embraced that betrayal, preferring the plastic facsimile that he became to the breaking news he once was. From Elvis to Marilyn Monroe to J.F.K. to Jackie O to James Dean to Princess Diana to all the other Madame Tussaud’s dummies, the mediaentertainment industry has exploited its icons past the point where their personal examples have anything vital to offer. Popular culture is suffering from icon exhaustion, having milked its sacred cows dry. The dead stars we profess to love won’t live again for us until they’re allowed forgiving rest.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

Subscribers have complete access to the archive.

Sign In Not a Subscriber?Join Now